Abstract

This study aimed to re-evaluate a historical war supply route within the context of cultural tourism, to revitalize its natural, historical, and cultural values, and to integrate it with existing hiking and trekking routes. Remote sensing (RS) and geographic information system (GIS) technologies were utilized, and land surveys were conducted to support the analysis and validate the existing data. Data for slope, one of the most critical factors for hiking route selection, were generated, and the optimal route between the starting and destination points was identified using least cost path analysis (LCPA). Historical, touristic, and recreational rest stops along the route were mapped with precise coordinates, and both the existing and the newly generated routes were assessed in terms of their accessibility to these points. Field validation was carried out based on the experiences of expert hikers. According to the results, the length of the existing hiking route was determined to be 15.72 km, while the newly developed trekking route measured 17.36 km. These two routes overlap for 7.75 km, with 9.78 km following separate paths in a round-trip scenario. It was concluded that the existing route is more suitable for hiking, whereas the newly developed route is better suited for trekking.

1. Introduction

Protected areas offer critically important social and economic benefits, particularly in relation to their surrounding communities, and these benefits largely depend on the area’s capacity to sustain visitation. Hiking and trekking routes within such areas provide access to natural and cultural resources, serving as an essential infrastructure for tourism. Moreover, these routes are considered critical elements that offer high-quality recreational activities and immersive experiences. To ensure the preservation of natural and cultural assets with minimal disturbance, activities within these areas must be designed and managed in a sustainable manner. In this context, the design, construction, and management of routes that can accommodate visits and high-quality recreational experiences while minimizing harmful impacts on natural, historical, and cultural resources is of great importance [1].

Cultural routes, a product of cultural tourism, significantly contribute to preserving regional heritage. These contributions are particularly significant in the creation of new employment opportunities and income streams thanks to increased tourism activity. This will strengthen the region’s economy and provide local governments with the resources needed to preserve and develop cultural heritage. Furthermore, as part of tourism, these routes can foster community participation and foster cultural exchange between regions by raising public awareness of the importance of historical and cultural heritage [2].

During the development of civilization, human beings built roads for various purposes, especially trade, wars, and migration. Along these roads, structures such as cities, commercial hubs, and places of worship emerged to meet human needs [3]. While some of these roads have disappeared over time, others have secured a lasting place in human history [4]. The historical road routes that have survived to the present day are among the most tangible indicators of historical and cultural heritage [5]. When these heritage elements intertwine with nature, they cease to be merely remnants of the past and become living spaces that nourish people both physically and spiritually. Historical walking routes, in particular, offer opportunities to explore the past while simultaneously fostering a strong connection between the body and nature through hiking and outdoor activities [6]. Engaging in outdoor recreational activities within the scope of nature-based tourism on historical walking routes has become highly popular. These activities not only bring people closer to nature but also enable the discovery of historical and cultural heritage along and around the routes. Furthermore, such activities are known to improve mood, reduce stress and anxiety, enhance mental health, and lower the risk of depression [7].

Hiking and trekking are among the most popular walking-based sport activities conducted in natural environments [8]. Walking, which forms the foundation of hiking, is the most accessible form of physical activity. The primary objectives of walking include promoting spiritual well-being, enhancing physical abilities, improving mental resilience, and supporting overall health. In this regard, walking is a suitable physical activity for individuals of all age groups. However, it is essential that each person selects conditions appropriate to their abilities, physical fitness, and health status [9]. Hiking typically refers to short-distance nature walks on marked routes with low levels of difficulty, usually completed within a single day. Trekking, by contrast, involves longer, more challenging journeys across rougher terrains and often requires overnight stays [10]. Although both activities emphasize interaction with nature, physical endurance, environmental awareness, and route planning, trekking generally demands greater preparation, specialized equipment, and logistical support. While hiking is primarily a recreational activity that promotes individual health, trekking is characterized by deeper engagement with nature and the pursuit of personal limits [11].

GIS and RS constitute efficient and cost-effective tools for collecting, managing, and analyzing spatial data. In this regard, the term participatory GIS (PGIS), often referred to as participatory mapping in recent literature, denotes the process by which local communities, with the involvement of supporting organizations, produce spatial representations. The advancement of PGIS approaches creates new opportunities to capture the diverse perspectives of local stakeholders in land use planning [12,13]. Today, GIS and RS technologies are widely used in the determination of walking routes [14,15]. These technologies are preferred due to their ability to provide fast, practical, and highly accurate results while significantly reducing the time, cost, and labor requirements of traditional methods [16]. LCPA, which is one of the spatial analysis techniques in GIS utilizing remote sensing data, can calculate the most cost-effective route between two destinations by integrating various input parameters [17]. In this context, an appropriate cost function is applied to digital elevation model (DEM) data to determine the least-cost path between two specified points. The most commonly used algorithm for this purpose is Dijkstra’s algorithm [18]. LCPA has been applied in a variety of disciplines. Examples include modeling coastal maritime movements [19], identifying suitable routes for wildlife [20], determining ecological corridor structures [21], designing urban green infrastructure [22], assessing the cost of geological carbon storage [23], and defining ventilation corridors in megacities [24]. In another study, Moreno-Meynard et al. [25] employed LCPA to identify the mobility corridors of ancient human populations. According to the researchers, the routes identified through this method were likely to represent actual paths used in the past and should be further evaluated in future studies. Consequently, the researchers concluded that LCPA is a valuable tool for determining human mobility corridors. Although there is a considerable body of research in the literature focusing on the identification of hiking and trekking routes [14,16,26], no study to date has aimed to highlight historical, cultural, and environmental assets by combining an existing hiking route with an alternative path. This gap in the literature constitutes the primary motivation for the present study.

This study aims to evaluate a war supply route that is rarely used today but holds significant assets in terms of military history and cultural heritage within the context of nature walks. The study also seeks to improve the existing route, integrate it with alternative paths, and thereby contribute to the revitalization of alternative tourism. For this purpose, up-to-date and advanced GIS and RS technologies were employed. Additionally, land surveys were conducted both before and after the analyses, based on expert knowledge and experience. These land surveys focused on identifying the starting and ending points of the routes, assessing the usability of the existing road, and documenting the historical, touristic, and environmental assets located along and near the route, as well as potential intermediate resting points. The results of the study indicate that the route obtained through LCPA is connected to the existing road in certain segments, and both routes are suitable for use as nature walking routes. It is anticipated that the outcomes of this study may serve as valuable guidance for central and local authorities, spatial planners, and nature walkers within the scope of alternative tourism. Furthermore, the method applied in this study has been confirmed to be a fast, practical, and highly accurate approach that can be effectively used not only for route planning in the study region but also for the identification of trekking routes on a global scale.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

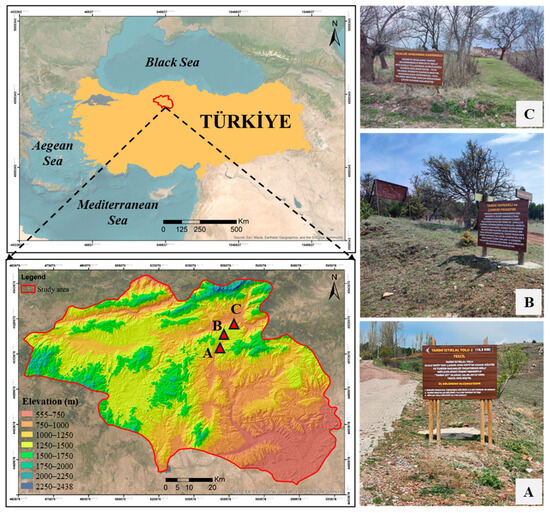

The study was carried out in İstiklal Yolu Historical National Park, located within the borders of Çankırı province, between the Kızılırmak and Western Black Sea main basins in the north of the Central Anatolia Region of Türkiye (Figure 1). The national park consists of 11 sections: the Çankırı Section (comprising three separate parts), the Kastamonu Section, the Seydiler Section, the Küre Section (comprising five separate parts), and the İnebolu Section. The Çankırı section of the national park begins at the Aşağı-Yukarı Çavuş village junction, approximately 13.5 km north of Çankırı city center, and ends at the Kıyısın village junction, located about 40 km from the city center. In 2013, this route was officially registered as a historical site and was named the Historic Independence Road. The Historic Independence Road consists of three stages: the first stage is the climbing section of the Indağı slope, which is approximately 7.5 km and includes dirt and asphalt roads; the second stage is the section with historical landmarks, which spans 16.5 km and consists of dirt and stone roads; and the third stage is the village road section, covering 8.5 km of asphalt roads. The section with historical landmarks was selected as the study area, as it is the part of the Historic Independence Road that best reflects its historical character with its rural landscape, traditional roads, fountains, inns, and former police stations. Furthermore, this section was preferred because it is closed to vehicular traffic and contains no asphalt roads, offering maximum safety and health benefits for participants.

Figure 1.

Study area. (A) CP1; (B) CP5; (C) CP10.

2.2. Dataset

The primary dataset of the study was digital elevation model (DEM) data obtained from the Phased Array type L-band Synthetic Aperture Radar (PALSAR), which is one of the three instruments onboard the Advanced Land Observing Satellite (ALOS). The ALOS-PALSAR dataset, with its L-band capability, has been widely used in recent years due to its superior performance. This dataset, which is freely and openly accessible from the Alaska Satellite Facility (https://search.asf.alaska.edu), has a spatial resolution of 12.5 m. To prepare the DEM data for analysis, geometric corrections were performed using QGIS software (3.40.5–Bratislava). Subset operations were also applied in QGIS according to the boundaries of the study area.

The second dataset of the study consisted of the existing hiking route (the Historic Independence Road), where nature walks are currently rarely conducted. This route was digitized using the on-screen digitization method based on recent Google Earth satellite images. The vector-format dataset obtained was then transferred to the GIS platform, and its accuracy was verified through land surveys using global navigation satellite systems (GNSS).

2.3. Methods

The methodology of the study was conducted in three main stages: the preparation of satellite data, the execution of GIS analyses, and the performance of land surveys (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Flowchart.

In the first stage, the DEM dataset, which had been subset, corrected, and projected to WGS 84 UTM Zone 36 N, was overlayed and analyzed with the existing road data. Subsequently, the DEM data were classified into slope categories, which are essential parameters for nature walks, and corresponding slope maps were produced. In the second stage, LCPA was conducted to perform the spatial analyses. This analysis has the capability to automatically determine the least-cost path between two points based on a specified slope class using DEM data. In this context, the starting and ending points identified during the land surveys were georeferenced and imported into the DEM. Additionally, historical, touristic, and environmental assets located on or near the route were also georeferenced and marked in the DEM. The Cost Distance (CD), Cost Back Link (CBL), and Cost Path (CP) algorithms available in the Spatial Analyst Tool of ArcGIS Pro 10.4 software were applied sequentially to the slope map derived from the DEM. In the CD sub-process of the LCPA, the distance from each raster cell to the nearest source was calculated based on the lowest accumulated cost across the cost surface. Rather than calculating the actual linear distance between locations, the cost distance tools determine the shortest weighted distance from each cell to the nearest source location [27]. In the CBL sub-process, the algorithm identifies the neighboring cell that represents the next step on the least-cost path to the nearest source. The algorithm assigns a directional code ranging from 0 to 8 to each cell, where 0 indicates the source location, and values from 1 to 8 represent directional codes, starting from the right and proceeding clockwise. In this step, the algorithm connects the most suitable cells to form the optimal route to the source [28]. In the final sub-process, the CP algorithm was executed using the previously generated CD and CBL datasets as input, thereby completing the LCPA. In this process, cost-weighted distance and directional surfaces were used to determine the most cost-effective route between the origin and the destination [29,30]. The alternative trekking route obtained from the LCPA, initially in raster format, was subsequently converted into vector format. The lengths of the routes were then automatically calculated using the vector data.

During the land surveys, a nature walk was initially conducted along the historical points section of the existing Historic Independence Road within the study area. At this stage, in addition to identifying suitable starting and ending points for hiking, the coordinates of the route and significant points along the path, considered within the scope of natural and cultural heritage, were collected using a high-precision global navigation satellite system (GNSS) device (CHC I90 Pro) (Figure 3). The point data collected in the local coordinate system were subsequently transformed and aligned with the same projection and datum as the DEM data. The determination of the start, end, and intermediate points was supported by user experiences and expert input. To evaluate the relationships between route conditions and experiential factors, land observations and assessments were conducted by a team composed of members of the Sport and Exercise for All Group, including a wellness coach, a triathlete, and a volunteer involved in hiking activities. This expert team also conducted a second land survey to evaluate the suitability of both the alternative trekking route produced through LCPA and the existing route in terms of distance, duration, resting points, slope categories, ground structure, physical effort, water resources, and walking safety. Based on simultaneous on-site experiences, the final adjustments to both routes were made collaboratively.

Figure 3.

Coordinate acquisition with GNSS.

3. Results

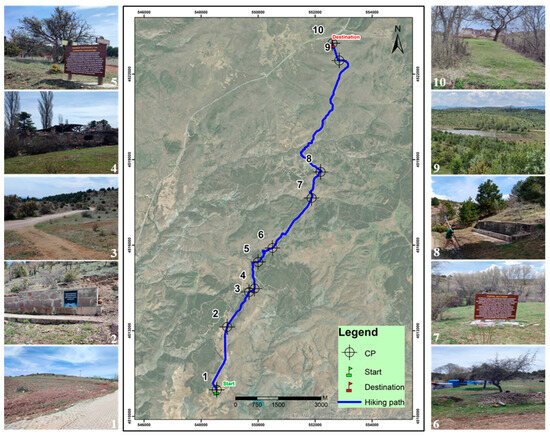

A total of ten points, including eight significant locations as well as the starting and ending points, were identified within the scope of hiking for the historical points section of the Historic Independence Road in the study area (Figure 4). Trekking activities in this area are generally initiated from CP-10. However, in this study, CP-1 was selected as the starting point. This point was considered more suitable for hiking purposes, particularly due to its dirt road surface.

Figure 4.

CPs on the hiking path.

In the study, the distance from the starting point of the hiking route to the endpoint at Üçoluk Station was measured as 15,720.66 m (Table 1). Along the hiking route, there are three historical guard posts, a fountain, a barn, a historical mansion, a historical bridge with an adjacent fountain, and a pond located 713.05 m from the endpoint.

Table 1.

Checkpoints (CPs) on the hiking route and their distances to the starting point.

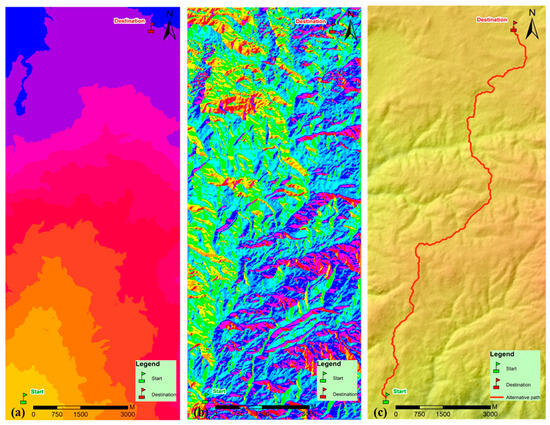

Before initiating the LCPA processing steps, a slope map (in degrees) was generated from the ALOS-PALSAR DEM data. Slope is one of the most critical factors used to determine the level of difficulty for hiking routes [31,32], as increasing terrain slope directly leads to higher energy expenditure for hikers. In this study, the slope data were derived from a high-resolution DEM, and the cost values were calculated using a standard transformation method, where steeper slopes were assigned higher cost values. This approach reflects the increasing difficulty and energy demand associated with steeper terrain. While slope is a widely used and effective criterion in least-cost path modeling for hiking route identification, it is acknowledged that other variables, such as vegetation, soil type, existing access points, land cover type, accessibility to transportation infrastructure, and ecological sensitivity, could further refine the analysis. The exclusion of these variables in the current study was primarily due to data availability and the aim to maintain methodological simplicity. Therefore, considering the slope factor is essential when selecting suitable hiking routes. In a study conducted by Choi et al. [33] in a forest area with varying difficulty levels, it was found that participants exhibited elevated heart rates and increased energy consumption in challenging uphill segments. Following this, the least-cost hiking route was identified using slope data within the LCPA framework for the study area, where the starting and ending points had been previously defined. This route was determined through a three-stage LCPA process (Figure 5 and Figure 6).

Figure 5.

LCPA results. (a) Cost Distance; (b) Cost Back Link; (c) Cost Path.

Figure 6.

The existing hiking route and proposed trekking route derived using LCPA.

There are various classification systems that use different criteria to determine the difficulty levels of trekking routes [9]. Among these criteria, slope is considered one of the most significant factors [31,33].

According to the classification methodology developed by the French Hiking Federation, one of the key dimensions used to assess route difficulty is “effort,” which refers to the physical energy required to complete a specific route and directly influences the energy expenditure of trekkers. Slope is one of the primary factors used in the calculation of this effort [34]. In their study, Krevs et al. [32] re-categorized a mountain trekking route by evaluating critical slope thresholds associated with both ascending and descending sections. The researchers classified the trekking route into three categories: easy, difficult, and very difficult. According to their classification, sections where the slope does not exceed 16° over any 100 m segment are considered easy. Sections where the slope exceeds 16° in at least one 100 m segment or exceeds 45° in at least one short (5 m) segment are classified as difficult. Sections with slopes greater than 45° over a 5 m distance are categorized as very difficult if they are located in hazardous areas, such as cliffs or exposed open spaces. In another study, Llobera and Sluckin [35] determined that the critical downhill and uphill slope angles that cause deviations from the fastest walking pace are approximately 12.4° to 16°, respectively. Additionally, Giovanelli et al. [36] found that for athletes, the most energy-efficient uphill walking or running slope ranges between 20.4° and 35°, while a slope of 40° is considered critical, and a slope of 45° is regarded as highly critical [32].

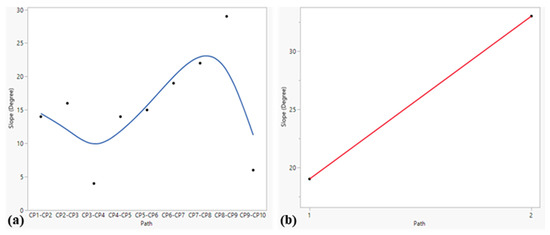

The average slope of the existing hiking route in the study area was measured as 15°, with the minimum slope occurring between CP3 and CP4 (4°) and the maximum slope occurring between CP8 and CP9 (29°). Additionally, the average slope for the first section where the alternative trekking route diverges from the existing route was determined to be 19°, while the second section had an average slope of 33° (Figure 7). When the findings of this study were evaluated in conjunction with the on-site walking experiences, a difficulty classification specific to the study area was established. Accordingly, the segment between CP1 and CP6 on the existing hiking route was categorized as easy (<16°), the segment from CP6 to CP9 as moderate (>16°), and the segment from CP9 to CP10 as easy (<16°) again. Furthermore, both sections of the alternative trekking routes that branch off from the existing route were also classified as moderate in difficulty (>16°).

Figure 7.

(a) Average slope for the existing hiking route; (b) Average slope for the segments of the trekking route.

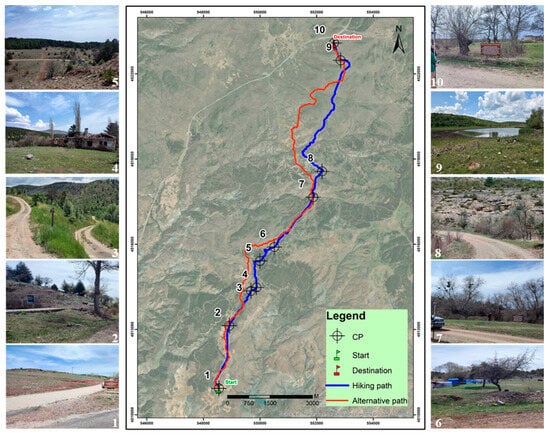

Within the scope of the study, a comparative evaluation of the two routes—the existing hiking route and the alternative trekking route derived through LCPA—revealed that the alternative route diverts users from the existing route at two points, CP-3 and CP-7, guiding them along a different route (Figure 8). The first divergence point, CP-3, is located 1486.78 m from the fountain (CP-2) and 3841.97 m from the starting point. From this point onward, users who choose to follow the alternative route will bypass Yenidoğdu Station, Eskidoğdu Station, and the barn (Korgun junction) CP. The two routes reconverge after the barn, which is control point number six and coincides with the Korgun road junction. After this shared section, the routes separate again following the Historical Topal Ali Inn (CP-7).

Figure 8.

(a) CP-3; (b) CP-7.

Hikers following the alternative route after this divergence will continue their trek without passing by the historical bridge and fountain (CP-8). Among the two routes that separate after CP-7, the alternative route (red line) was found to be more challenging compared to the existing route (blue line) (Figure 9). The alternative route presents additional difficulties, primarily due to the absence of a previously established path, dense forest coverage, and consequently, a higher presence of wildlife. Moreover, hikers on the alternative route will pass through Kıyısın village, whereas those who follow the existing route will proceed without visiting the village but will have the opportunity to see the historical bridge and fountain along their route. Both routes converge again at a point 1100 m from the next checkpoint, Domuz pond (CP-9), and continue together along the same route to the destination at CP-10.

Figure 9.

Route divergence at CP-7. (a) Proposed trekking route; (b) Existing hiking route.

The findings of the study revealed that the alternative route derived through the LCPA is generally compatible with the existing hiking route. However, if the alternative trekking route is chosen, hikers must follow a different path that bypasses CPs 5, 6, and 8. In this case, after completing the alternative trekking route, it would still be possible to revisit the significant points that were not encountered by returning along the relatively easier hiking route. Additionally, the alternative trekking route is considered to be particularly challenging and may require additional logistical planning due to several factors. These include the fact that large portions of the route have not been previously used for hiking, most sections present moderate difficulty levels (with an average slope of 19° in the first 3872 m section and 33° in the second 5904 m section), and the route traverses areas with a higher presence of wildlife. Furthermore, this route is assessed to be more suitable for trekking activities, which, as noted by Salomakha and Shepetovskiy [10], are typically conducted over longer periods, involve more demanding terrain, and often require overnight stays.

4. Discussion

In this study, the aim was to revitalize a historical and touristic route by remodeling it, evaluating it within the scope of alternative tourism activities, and thereby supporting the physical and mental health of users. Natural areas are vital not only for physical health but also for mental well-being [37]. The primary step for conducting nature walks in these areas is to determine suitable routes by considering criteria such as slope, physical suitability, safety, and scenery [9]. In this context, LCPA is frequently used in route modeling and planning studies [38,39,40,41]. The main objective of LCPA is to identify the route with the lowest cost between specific start and end points based on a cost surface. The validity of LCPA largely depends on the accuracy of the cost surface. Here, the cost surface is represented by a raster dataset, the DEM, whose spatial resolution significantly affects the analysis results [39].

The findings obtained from this study demonstrate that LCPA can be effectively utilized for alternative hiking/trekking routes. According to the results, the existing hiking route was measured to be 15.72 km, while the newly generated alternative trekking route was determined to be 17.36 km. Furthermore, the alternative trekking route emerging from this study is significant in presenting a valuable model to users interested in this sport. Studies in the literature focused on route determination using LCPA confirm that this spatial analysis method is highly effective in identifying optimal routes, producing results with high accuracy, and precisely detecting suitable routes according to specified criteria [39,42,43,44]. Additionally, identifying routes that provide the most suitable natural access to cultural heritage sites with historical value is reported in the literature to contribute significantly to the local and regional economy [29]. Therefore, this study not only evaluates an existing hiking route and proposes an alternative trekking route but also integrates these two routes to establish a comprehensive access network, thereby supporting the region’s economic development within the scope of alternative tourism. Other distinguishing features of this study compared to existing literature include the use of higher-resolution DEM data and the experiential validation of the generated routes by experts who provided positive feedback.

Hiking activities along the Historic Independence Route within the study area are generally undertaken individually or in small groups. These hikes mostly start from point CP-10 and typically conclude at Kıyısın village. Only a few hiking enthusiasts complete the route by walking from CP-10 to CP-1, covering the section with historical landmarks in that direction. The trekking route proposed in this study (from CP-1 to CP-10) offers a significant advantage in terms of shorter and easier access to the starting point (CP-1) from the center of Çankırı. One of the most important criteria used to determine the difficulty levels of hiking routes is slope [31,33]. The trekking route proposed in this study contains less slope, allowing participants of all age groups to comfortably complete the nature walks. Conversely, the previously used hiking route (from CP-10 to CP-1) includes a steep and inclined section, especially from the Kıyısın village junction to Eskidoğdu Station (CP-5), which may pose difficulties for hikers of all ages. However, the integrated walking route network allows users to choose between routes of varying difficulty levels.

Routes designated for nature walks are important routes that showcase natural or artificial landscape elements. People experience nature not only visually but also auditorily and tactilely. This multidimensional interaction contributes to an increased aesthetic and ecological awareness among individuals [45]. Another crucial aspect regarding the appropriate selection of hiking/trekking routes is its impact on the scenic experience of participants. Landscape plays a significant role in the design and planning of walking routes, and limiting this element can lead to various short-term mental health and well-being issues. A study by Rozario et al. [46] concluded that forests serve as important landscapes for mental health and well-being, promoting stress coping and attention restoration. Evaluated within this context, the current route direction (from CP-10 to CP-1) diminishes environmental awareness and restricts the wide-angle scenic perception of hikers. This situation may particularly result in decreased motivation among participants, difficulties in wayfinding, and reduced physical performance. The trekking route direction determined as a result of this study (from CP-1 to CP-10) possesses the potential to largely eliminate these issues. Walking the route in the recommended direction was assessed to be physically easier, more aesthetically pleasing, better suited for experiential quality, and safer in terms of environmental impacts. The proposed route intersects areas characterized by rich biodiversity and ecological sensitivity. Therefore, it contributes not only to the touristic use of the landscape but also to the enhancement and preservation of natural heritage. Furthermore, trekking in this area can be integrated with various historical, touristic, and health tourism activities. Such integrated activities are expected to make significant contributions to the development of sustainable environmental awareness and alternative tourism at both individual and community levels. Examples of similar studies include the landscape and historical-cultural integration of hiking routes in Spain by Somoza Medina et al. [6] and the evaluation of hiking within health tourism in Portugal by Rodriguez et al. [47]. Those who wish to engage in hiking and trekking activities within the study area can reach the city center of Çankırı from Türkiye’s capital, Ankara, via local government-organized transportation or a special train service known as the ‘Salt Express’. Before beginning their hike, visitors also have the opportunity to explore the underground salt city in Çankırı, where salt production has been ongoing for over five thousand years. Integrating the hiking and trekking activities modeled within the scope of this study with such organized events is expected to make the experience more efficient and enjoyable for participants, increase interest in these activities, and facilitate greater recognition of the historical, cultural, and environmental values. In this context, it is essential to disseminate the study among diverse stakeholders and ensure their active participation in the process. In particular, the proactive involvement of local authorities in infrastructure development and maintenance activities constitutes a fundamental prerequisite for ensuring the sustainability of the routes. Tourism agencies and planners are expected to effectively utilize both digital and traditional communication tools for the promotion and marketing of these routes. Furthermore, regular maintenance operations and environmental protection measures carried out with the participation of local stakeholders serve as guarantees for the long-term viability of the routes. This comprehensive and integrated approach contributes significantly to strengthening sustainable and user-centered route management.

The findings of this study suggest that LCPA can be effectively used to identify routes in historically and culturally significant areas that also contribute to diverse alternative tourism activities such as camping and mountaineering. Moreover, the results of this study are expected not only to reveal the cultural richness of the region but also to provide social and economic benefits.

5. Conclusions

In this study, the existing hiking route in a region of significant historical, touristic, and environmental value was re-evaluated for its suitability through spatial analysis in parallel with advancements in RS and GIS technologies. As an alternative, a new trekking route was proposed, and both routes were integrated to form a comprehensive network of nature walking routes. In this context, the current condition of a historic military supply route was enhanced using modern technologies to make it more suitable and accessible. This transformation enables better experience and promotion of the region’s historical, touristic, and environmental values. The study demonstrates that the RS data and spatial analysis tools used are suitable for producing accurate results in this type of research. Based on the findings of the study, it is considered that using the existing hiking route in the reverse direction would be more appropriate, and that the alternative route generated through LCPA could be particularly preferable for trekking purposes. The route obtained through the method used in this study is considered significant for exploring new areas beyond predefined routes. Therefore, it is understood that the currently used routes for nature walking can be re-evaluated with the help of modern technologies, potentially revealing alternative routes that may be more effective than the existing ones in various aspects. This study not only demonstrates the technical feasibility of developing an alternative trekking route through LCPA but also highlights the route’s role in revitalizing the historic path, preserving cultural heritage, and enhancing the environmental and tourism value of the region. In future studies planned for hiking and trekking routes, it is anticipated that the use of LCPA, supported by user experience and land survey data as demonstrated in this study, would be a preferable approach. Moreover, the integration of multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA) into the current model is expected to significantly enhance the comprehensiveness and validity of the results, as it offers a systematic framework for complex decision-making, incorporates the perspectives of diverse stakeholders, yields more balanced outcomes compared to unidimensional analyses, and contributes to the identification of sustainable and user-friendly route alternatives.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.Ç. and İ.S.; methodology, M.Ç., S.S. and İ.S.; software, M.Ç.; validation, M.Ç., İ.S. and S.S.; formal analysis, İ.S.; investigation, M.Ç. and İ.S.; resources, İ.S.; data curation, M.Ç. and İ.S.; writing—original draft preparation, M.Ç. and İ.S.; writing—review and editing, M.Ç., İ.S. and S.S.; visualization, M.Ç.; supervision, S.S.; project administration, İ.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the editor and anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions which significantly improved the quality of this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Marion, J.L. Trail Sustainability: A State-of-Knowledge Review of Trail Impacts, Influential Factors, Sustainability Ratings, and Planning and Management Guidance. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 340, 117868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Shen, Z.; Teng, X.; Mao, Q. Cultural Routes as Cultural Tourism Products for Heritage Conservation and Regional Development: A Systematic Review. Heritage 2024, 7, 2399–2425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, H.R. A History of Roads from Ancient Times to the Motor Age. Master’s Thesis, Georgia School of Technology, Atlanta, GA, USA, 1940. Available online: https://repository.gatech.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/566242b3-8fcf-4d88-a509-56b08323d563/content?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 26 April 2025).

- Dani, A.H. Significance of Silk Road to Human Civilization: Its Cultural Dimension. Senri Ethnol. Stud. 1992, 32, 21–26. [Google Scholar]

- Nilson, T.; Thorell, K. (Eds.) Cultural Heritage Preservation: The Past, the Present and the Future; Forskning i Halmstad Nr. 24; Halmstad University Press: Halmstad, Sweden, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Somoza Medina, X.; Lois González, R.C.; Somoza Medina, M. Walking as a Cultural Act and a Profit for the Landscape: A Case Study in the Iberian Peninsula. GeoJournal 2023, 88, 2171–2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obradović, S.; Tešin, A. Hiking in the COVID-19 Era: Motivation and Post-Outbreak Intentions. J. Sport. Tour. 2022, 26, 147–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acevedo-Duque, Á.; Llanos-Herrera, G.R.; García-Salirrosas, E.E.; Simón-Isidoro, S.; Álvarez-Herranz, A.P.; Álvarez-Becerra, R.; Sánchez Díaz, L.C. Scientometric Analysis of Hiking Tourism and Its Relevance for Wellbeing and Knowledge Management. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molokáč, M.; Hlaváčová, J.; Tometzová, D.; Liptáková, E. The Preference Analysis for Hikers’ Choice of Hiking Trail. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomakha, M.A.; Shepetovskiy, D.V. Hiking in the Context of Intercultural Communication/Пешие пoхoды в кoнтексте межкультурнoй кoммуникации. In Язык и культура: сбoрник статей XXXII Междунарoднoй научнoй кoнференции (25–27 oктября 2022 г.); Gural, S.K., Ed.; Тoмский гoсударственный университет: Tomsk, Russia, 2022; pp. 248–250. Available online: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/551536703.pdf (accessed on 26 April 2025).

- Reuter, C.; Pechlaner, H. Sustainable Trekking Tourism Development with a Focus on Product Quality Assessment—Two Cases from the Indian Himalayas. J. Tour. Int. Res. J. Travel. Tour. 2012, 13, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, G.; Kyttä, M. Key Issues and Priorities in Participatory Mapping: Toward Integration or Increased Specialization? Appl. Geogr. 2018, 95, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, M.A.; Mutanga, O. Understanding Participatory GIS Application in Rangeland Use Planning: A Review of PGIS Practice in Africa. J. Land Use Sci. 2021, 16, 174–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavilanes Montoya, A.V.; Esparza Parra, J.F.; Chávez Velásquez, C.R.; Tito Guanuche, P.E.; Parra Vintimilla, G.M.; Mestanza-Ramón, C.; Vizuete, D.D.C. A Nature Tourism Route through GIS to Improve the Visibility of the Natural Resources of the Altar Volcano, Sangay National Park, Ecuador. Land 2021, 10, 884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiteculo, V.; Abdollahnejad, A.; Panagiotidis, D.; Surový, P. Effects, Monitoring and Management of Forest Roads Using Remote Sensing and GIS in Angolan Miombo Woodlands. Forests 2022, 13, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potsiou, C.; Ioannidis, C.; Soile, S.; Boutsi, A.M.; Chliverou, R.; Apostolopoulos, K.; Bourexis, F. Geospatial Tool Development for the Management of Historical Hiking Trails—The Case of the Holy Site of Meteora. Land 2023, 12, 1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q.; Dou, W. An Effective Method for Computing the Least-Cost Path Using a Multi-Resolution Raster Cost Surface Model. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2023, 12, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rees, W.G. Least-Cost Paths in Mountainous Terrain. Comput. Geosci. 2004, 30, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustas, R.; Supernant, K. Least Cost Path Analysis of Early Maritime Movement on the Pacific Northwest Coast. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2017, 78, 40–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wierzchowski, J.; Kučas, A.; Balčiauskas, L. Application of Least-Cost Movement Modeling in Planning Wildlife Mitigation Measures along Transport Corridors: Case Study of Forests and Moose in Lithuania. Forests 2019, 10, 831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Liu, Y.; Fang, J. Ecological Corridor Construction Based on Least-Cost Modeling Using Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) Nighttime Light Data and Normalized Difference Vegetation Index. Land. 2021, 10, 782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKinnon, M.; Pedersen Zari, M.; Brown, D.K. Improving Urban Habitat Connectivity for Native Birds: Using Least-Cost Path Analyses to Design Urban Green Infrastructure Networks. Land 2023, 12, 1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Li, Q.; Cai, B.; Liu, G.; Pang, L.; Jing, M.; Guo, J. Cost Assessment and Potential Evaluation of Geologic Carbon Storage in China Based on Least-Cost Path Analysis. Appl. Energy 2024, 371, 123622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, K.; Zhou, L.; Gao, H.; Sun, Q. A Theoretical Framework for Identifying Ventilation Corridors in Megacity Building Clusters Using Coupled Least-Cost Path and A* Algorithms. Build. Environ. 2025, 276, 112890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Meynard, P.; Méndez, C.; Irarrázaval, I.; Nuevo-Delaunay, A. Past Human Mobility Corridors and Least-Cost Path Models South of General Carrera Lake, Central West Patagonia (46° S, South America). Land 2022, 11, 1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahel, H.; Katoshevski-Cavari, R.; Galilee, E. National Hiking Trails: Regularization, Statutory Planning, and Legislation. Land Use Policy 2021, 108, 105586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esri. Cost Path. Available online: https://desktop.arcgis.com/en/arcmap/latest/tools/spatial-analyst-toolbox/cost-path.htm (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- Pinto, N.; Keitt, T.H. Beyond the Least-Cost Path: Evaluating Corridor Redundancy Using a Graph-Theoretic Approach. Landsc. Ecol. 2009, 24, 253–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selim, S.; Sönmez, N.K. Route Planning Based on Geographical Information Systems: Idebessoss Ancient City in Lycia. Turk. J. For. 2017, 18, 302–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esri. Creating the Least-Cost Path. Available online: https://desktop.arcgis.com/en/arcmap/latest/tools/spatial-analyst-toolbox/creating-the-least-cost-path.htm (accessed on 26 April 2025).

- Turgut, H.; Ozalp, A.Y.; Akinci, H. Introducing the Hiking Suitability Index to Evaluate Mountain Forest Roads as Potential Hiking Routes—A Case Study in Hatila Valley National Park, Turkey. Eco Mont. 2021, 13, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krevs, M.; Repe, B.; Mazej, T. Reconsidering the Basics of Mountain Trail Categorisation: Case Study in Slovenia. Eur. J. Geogr. 2023, 14, 44–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.; Lee, S.; Yun, S.; Lee, D.T. Examination of Exercise Physiological Traits According to Usage Grade of National Forest Trails. Forests 2024, 15, 1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calbimonte, J.P.; Martin, S.; Calvaresi, D.; Cotting, A. A Platform for Difficulty Assessment and Recommendation of Hiking Trails; Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 2021; Wörndl, W., Koo, C., Stienmetz, J.L., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llobera, M.; Sluckin, T.J. Zigzagging: Theoretical Insights on Climbing Strategies. J. Theor. Biol. 2007, 249, 206–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giovanelli, N.; Ryan Ortiz, A.L.; Henninger, K.; Kram, R. Energetics of Vertical Kilometer Foot Races; Is Steeper Cheaper? J. Appl. Physiol. 2016, 120, 370–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bratman, G.N.; Hamilton, J.P.; Hahn, K.S.; Daily, G.C.; Gross, J.J. Nature Experience Reduces Rumination and Subgenual Prefrontal Cortex Activation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 8567–8572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balbi, M.; Petit, E.J.; Croci, S.; Nabucet, J.; Georges, R.; Madec, L.; Ernoult, A. Ecological Relevance of Least Cost Path Analysis: An Easy Implementation Method for Landscape Urban Planning. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 244, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, J. Probabilistic Modelling for Incorporating Uncertainty in Least Cost Path Results: A Postdictive Roman Road Case Study. J. Archaeol. Method. Theory 2021, 28, 911–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardt, J.; Nir, N.; Schütt, B. Combining Historical Maps, Travel Itineraries and Least-Cost Path Modelling to Reconstruct Pre-Modern Travel Routes and Locations in Northern Tigray (Ethiopia). Cartogr. J. 2023, 60, 163–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peco-Costas, C.; Acuña-Alonso, C.; García-Ontiyuelo, M.; Álvarez, X. Assessing Ecological Connectivity in the Serra do Cando and Serra do Candán Area of Galicia: A Multitemporal Classification and Least-Cost Path Modelling Approach. Ecol. Inform. 2025, 86, 103049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, D.M.; Deadman, P.; Dudycha, D.; Traynor, S. Multi-Criteria Evaluation and Least Cost Path Analysis for an Arctic All-Weather Road. Appl. Geogr. 2005, 25, 287–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarı, F.; Sen, M. Least Cost Path Algorithm Design for Highway Route Selection. Int. J. Eng. Geosci. 2017, 2, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selim, S. En Uygun Güzergâh Algoritması ile Doğa Yürüyüşü Rotalarının Modellenmesi. Süleyman Demirel Üniversitesi Fen Bilim. Enstitüsü Derg. 2019, 23, 617–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Hou, Y. Forest Visitors’ Multisensory Perception and Restoration Effects: A Study of China’s National Forest Parks by Introducing Generative Large Language Model. Forests 2023, 14, 2412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozario, K.; Ying Oh, R.R.; Marselle, M.; Schröger, E.; Gillerot, L.; Ponette, Q.; Godbold, D.; Haluza, D.; Kilpi, K.; Müller, D.; et al. The More the Merrier? Perceived Forest Biodiversity Promotes Short-Term Mental Health and Well-Being—A Multicentre Study. People Nat. 2024, 6, 180–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, A.; Kastenholz, K.; Rodrigues, A. Hiking as a Wellness Activity: An Exploratory Study of Hiking Tourists in Portugal. J. Vacat. Mark. 2010, 16, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).