1. Introduction

Since the United Nations’ Brundtland Report (1987) [

1], which formalized the concept of sustainability based on three pillars—environmental, economic, and social—key advancements have been reported in environmentally sustainable packaging. Companies’ engagement has created momentum, and packaging plays a crucial role in sustainability [

2]. Beyond ensuring food quality and safety, it facilitates transportation, logistics, and communication. Regardless of companies’ recent efforts to use more sustainable packaging to protect and transport their products, there is still room for improvement. Companies and the packaging industry face complex environmental protection, social justice, and economic growth challenges, defining features of the early 21st-century global landscape. To navigate these challenges, they must prioritize sustainability while addressing climate change, social inequality, and economic instability. By doing so, they can contribute to a more equitable, resilient, and sustainable future [

2].

According to García-Arca et al. [

3], stakeholders such as consumers, shareholders, public administrations, and unions are increasingly concerned about implementing sustainable policies in supply chain management. Looking ahead, packaging can also support and promote improvements and innovations in the sustainable management of supply chains [

3]. A multifunctional vision has led to the development of the “sustainable packaging logistics” approach, which involves integrating packaging design, logistics management, and new product development. However, the question regarding whether there are paths for companies to use for sustainable packaging that may be further incentivized and embraced by companies remains.

Therefore, this study aims to understand how companies confront and integrate sustainability challenges in packaging design, as well as the motivations and processes influencing managers’ decisions to adopt sustainable behaviors. These decisions are subsequently reflected in their internal strategies, business plans, and operations.

A multi-case study involving five leading Portuguese companies (hereafter referred to as Company A, Company B, Company C, Company D, and Company E) was developed to understand companies’ perceptions and actions that may translate into progress in sustainable packaging. For this purpose, the literature review is presented, along with different topics related to sustainable packaging and the focus of this study. Secondly, the conceptual model approach is introduced, followed by an analysis, discussion, and explanation of the main findings from the companies’ interviews. Finally, the conclusions are presented, along with a description of this study’s main limitations and suggestions for future studies.

2. Literature Review

The increasing awareness of environmental issues and the growing demand for sustainable products have led to significant interest in sustainable packaging.

Plastic packaging represents one of the most persistent forms of waste, contributing significantly to global pollution: data show that plastics make up more than 60% of marine litter, and around 10–40 million tons of microplastics are released into the environment annually [

4]. These microplastics accumulate in food chains and have been detected in human tissues, including blood, lungs, and placenta, raising concerns about potential health risks such as inflammation, oxidative stress, and endocrine disruption [

5]. Such pressing environmental and health issues are key drivers behind the industry’s shift towards more sustainable packaging solutions.

This literature review focuses on sustainable packaging from the perspective of companies and on the external and internal factors that influence companies’ behaviors and actions in opting for more sustainability in packaging design.

2.1. Sustainable Packaging

Sustainable development was first defined in the 1987 Brundtland Report [

1], Our Common Future, published by the United Nations Commission on Environment and Development, as “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.”

Although “sustainability” gained widespread attention in the late twentieth century, its foundational concept has existed for centuries. For example, early civilizations applied sustainable practices in food packaging to preserve food between harvests. In contemporary societies, these principles continue to influence packaging practices. Over time, the concept of sustainability has been formalized and expanded by organizations, corporations, non-governmental organizations, and policymakers. It has been applied across various sectors, resulting in over 300 recognized definitions of the term [

2].

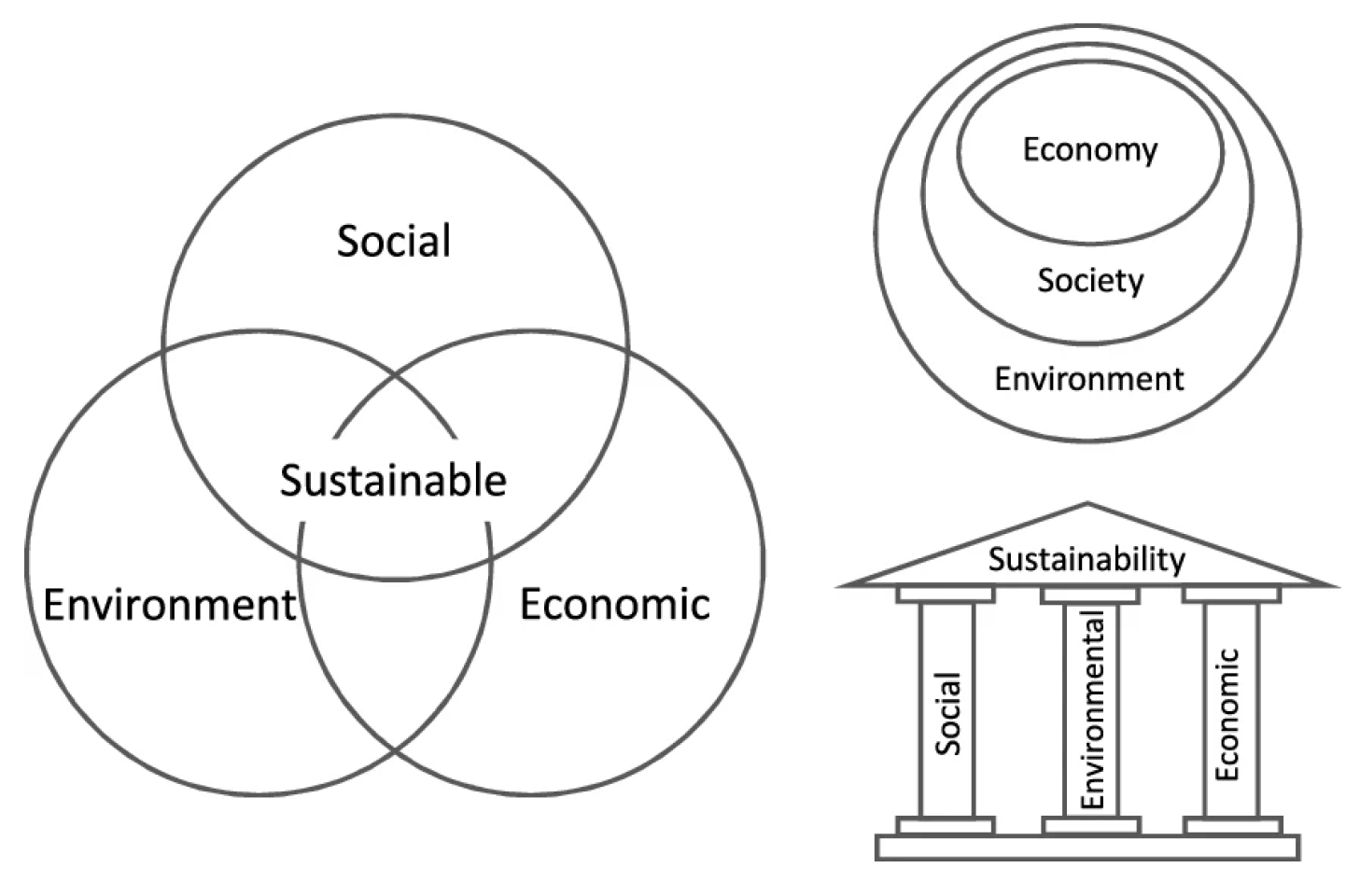

The Three Pillars Sustainability Model, illustrated in

Figure 1, is a widely accepted framework for understanding sustainability. This model identifies three fundamental and interconnected dimensions: environmental protection, social equity, and economic viability. For any strategy or solution to be considered sustainable, it must address all three pillars in a balanced and integrated way.

In the specific context of packaging, Rezaei et al. [

6] propose that packaging should be viewed as a system composed of three hierarchical levels. The first level, primary or consumer packaging, is designed to protect the product. The second level, or secondary packaging, groups several primary units to facilitate handling and transport. The third level, tertiary packaging, combines primary or secondary units into larger logistic units, such as pallets, to support bulk distribution.

In addition to these structural levels, packaging fulfills three core functions. The marketing function concerns design, branding, and compliance with regulations and consumer expectations. The logistics function supports procurement, production, packing, and distribution processes. The environmental function focuses on sustainability goals, particularly through reverse logistics and material recovery practices.

Criteria for defining sustainable packaging vary by region and are developed by specialized institutions. The European Organization for Packaging and the Environment (EUROPEN) guides in Europe. The Sustainable Packaging Coalition (SPC) leads similar efforts in the United States. In Australia, the Sustainable Packaging Alliance (SPA) promotes sustainable design. These organizations have developed specific standards, as illustrated in

Table 1, that guide the development of environmentally responsible packaging solutions.

2.2. Sustainable Packaging Design and Marketing

Consistent with Rundh [

7], new packaging solutions offer improved functions in the supply chain, delivering protection and preservation before reaching the ultimate customer. They offer companies improved opportunities for better information and communication with the customer, and companies’ interest in packaging as a sales promotion tool is growing increasingly. The transparency and readability of information on the packaging are equally important, such as information on the content, benefits, legal regulations, brand value, or technical issues related to intelligent packaging [

7]. The visual attractiveness of the packaging, for instance, enriching the colors and lines on the package with different signs and symbols and different materials, can inspire customers to touch the package, encouraging them to try it. Improving the image of the packaging is often a factor that largely determines the choice of the product [

7].

Currently, packaging consists of three functions in the market: logistics, commercial, and environmental. Therefore, the many purposes of packaging have also led to over-packaging and unsustainable uses. The relationship between increased costs for packaging solutions and their influence on the environment must be analyzed in terms of increased costs for packaging [

7]. According to Zhang & Yang [

8], packaging is seen as both beneficial and problematic for marketing. Effective packaging helps products gain a positive position in marketing strategies, whereas poor packaging can hinder product development.

As modern society develops, people’s consumption continues to grow, and packaging becomes increasingly important in marketing [

8]. In this regard, companies can incorporate modern design concepts and packaging technologies based on product characteristics and actively adopt different strategies to enhance marketing development. As Rundh [

7] pointed out, companies have realized that packaging can affect consumers’ decision-making more than ever. Furthermore, packaging can improve the performance of the business, standardize logistics, and minimize operational costs, providing the market with a pro-environmental image with a high sense of responsibility.

2.3. External Factors Influencing Companies’ Decisions on Sustainable Packaging

2.3.1. Perception of Consumers and Competitors

Barriers like value chain complexities and negative consumer attitudes may discourage companies from implementing more sustainable packaging [

2]. Nonetheless, eco-friendly purchasing and disposal decisions could be linked to consumers’ environmental awareness and their eco-friendly attitudes. A study by van Birgelen [

9] on packaging and pro-environmental consumption shows that consumers may be willing to trade off products based on almost all attributes in favor of environmentally friendly packaging, except for taste and price.

Although people’s minds and attitudes are becoming more sustainability-oriented, their buying behavior does not reflect this tendency. Various factors can influence consumers’ environmental buying objectives [

10]. One of these is the person’s environmental consciousness and motivation. Consumers with higher environmental consciousness and awareness make better choices than those with lower levels [

11]. Awareness and social pressure (such as family and friends’ attitudes towards sustainability) add to the individual’s view on the personal opportunity of contributing to a solution to an ecological issue [

10].

Despite changes in consumption habits, the notion of a “throw-away” society has grown stronger [

12]. Without guaranteed incentives to switch to ecological production and packaging, most companies avoid adopting more sustainable logistics and packaging developments [

13]. As consumers become increasingly familiar with sustainable packaging, companies and policymakers have recognized the need to respond to the growing demand for sustainability initiatives [

2]. However, decision-makers face challenges such as costs, time to market, technical difficulties, and team alignment [

14]. Consequently, many sustainable packaging solutions that do not meet favorable economic and time parameters are not implemented, as van Birgelen et al. [

9] noted.

2.3.2. Legislative Framework

Another issue that may be an incentive or a limitation for companies’ actions on sustainable packaging relates to the legislative framework. According to Guillard et al. [

15], the next step in achieving sustainable packaging will be considering the package’s legal requirements. The authors also stress the need to develop convincing, sustainable packaging materials. This could be achieved by enhancing the conversation with an unbiased and transparent eco-efficiency assessment. Materials should be tailored to usage requirements while optimizing costs [

15].

In November 2022, the European Commission published the proposal COM/2022/677 for regulating packaging and packaging waste (amending Regulation 2019/2020 and Directive 2019/904 and repealing Directive 94/62/EC), which standardizes the requirements for packages as well as packaging waste prevention and management. All packaging used in the EU market must comply with essential requirements relating to its composition, reusability, and recoverability. The initiative aims to tackle the limited competitiveness of secondary materials from recycled packaging relative to virgin feedstock, given their quality and availability, and address the increase in packaging waste generation.

Furthermore, all packaging materials intended for food contact in the European Union must comply with Regulation (EC) No 1935/2004, which establishes safety and inertness standards to prevent the harmful migration of substances into food. Complementarily, Regulation (EU) 2019/1381 reinforces transparency and public trust in food chain risk assessments. These frameworks are increasingly relevant in guiding the design of sustainable food packaging. In parallel, the European Commission has proposed a ban on single-use plastic packaging starting in 2030, adding further urgency for companies to adopt legally compliant and environmentally responsible alternatives [

16].

2.3.3. Companies’ Views on Sustainable Packaging Developments

Much research has been conducted on developing bio-packaging solutions, such as bio-based packaging materials made from renewable resources and/or biodegradable materials, by the packaging industry to achieve increased sustainability. However, packagers face the challenge of overcoming specific technical issues with these bio-packaging materials that currently limit significant market adoption. Additionally, the lack of tools to (1) help users tailor packaging to food needs (such as matching packaging performance to food requirements) and (2) assess the true sustainability of bio-packaging innovations and packaging as a whole, prevents stakeholders from fully recognizing the economic, societal, and environmental opportunities of these innovations. In the fast-changing food packaging industry, marketed innovations emphasize practicality, ease of use, and visual appeal to attract consumers. Some of these innovations claim to be sustainable either due to their materials (bio-based) or their end-of-life disposal (biodegradable), but they often lack a thorough and fair evaluation of their overall environmental benefits. Many of these eco-friendly innovations are less eco-friendly than expected.

For example, (i) materials differ greatly in the amount of renewable resources used in their composition, and (ii) they may or may not be easily compostable, as often claimed [

15]. Several life cycle assessment reviews have shown that the production of bioplastics, such as PLA or PHA, can involve high energy and water use, as well as significant greenhouse gas emissions, depending on the feedstock and production process [

17]. Similarly, paper-based or multilayer packaging, often viewed as sustainable, may contain plastic coatings or adhesives that severely hinder recycling and contaminate waste streams [

18]. Moreover, bio-based alternatives using crops like maize or sugarcane may contribute to land-use change, eutrophication, and carbon-intensive agriculture, thus limiting their overall positive environmental impact [

19]. These examples underscore the need for a thorough life cycle perspective when assessing the true sustainability of packaging innovations.

Previous research shows that supplier knowledge of sustainability management tools, technologies, and practices, as well as receptivity to new ideas about innovations in sustainable operations, are critical for suppliers to adopt sustainable practices [

20]. Such knowledge will influence suppliers’ capability to absorb knowledge from buyer companies [

21] to develop tools and sustainable practices. Buyers depend on supplier development initiatives to motivate and guide their suppliers to adopt sustainable practices [

22]. Consistent with Dou et al. [

23], supplier development for sustainability includes competitive pressure and incentives.

2.4. Internal Factors Influencing Companies’ Decisions on Sustainable Packaging

2.4.1. Companies’ Strategies for Sustainable Packaging

Sustainable packaging-related concepts have evolved with the increasing incorporation of sustainable development principles at various levels into industrial and organizational platforms [

2]. Moreover, for almost a decade now, Europe has been investing in research in packaging technologies, which is perceived as a robust market with immense potential [

15]. However, packages with improved sustainability may never make their way into the marketplace [

2]. Furthermore, almost half of the food and packaging industry specialists are unaware of the newly available technologies [

15]. Despite efforts, there is room for improvement, especially in the packaging value chain, by enhancing collection and sorting, recycling, composting, reuse, and waste-to-energy processes, as well as adopting more sustainable materials—all while reducing material use and preserving essential packaging functions [

2].

Companies’ efforts in integrating sustainable packaging into their strategies are demonstrated by the Sustainable Packaging Coalition, which compiles the goals and outlines the packaging sustainability targets of various companies [

2]. For example, McDonald’s, Unilever, Nestlé, Kraft-Heinz, PepsiCo, and Coca-Cola have set targets in their action plans to improve their packaging’s sustainability by 2025 and beyond. Targets include increasing recycling and the use of recycled materials, reducing reliance on virgin materials, promoting sustainable sourcing, reducing weight, and enhancing packaging design for easier recovery, among other efforts and actions. Such commitments require a significant investment of resources, including capital, with the expectation of enhancing market and consumer satisfaction through the selection and design of packaging elements, materials, and modifications across the value chain. However, the efficiency of companies’ strategies for new packaging solutions to decrease the global environmental effect of the food packaging system was never evaluated on a large scale, nor conveyed in an easy-to-understand format to consumers [

2].

2.4.2. Impact of Sustainable Packaging on Business Models and Operations

Guillard et al. [

15] suggested that multiple internal factors hinder the success of sustainable packaging solutions in the market, as noted by Boz et al. [

2]. For active packaging solutions to be commercially viable and successfully adopted by the market, they must meet regulatory requirements while ensuring the intended efficacy and limited impact on the sensory properties of food [

15]. However, unless it can be proven that implementing sustainable packaging drives sales or reduces costs, companies lack the business case, despite their sustainability intentions.

Among the most promising innovations in sustainable packaging are active and intelligent packaging (AIP) solutions. Active packaging incorporates components like oxygen scavengers, antimicrobial agents, or moisture absorbers directly into packaging materials to extend shelf life and ensure safety. Intelligent packaging employs sensing and communication technologies, such as time–temperature indicators (TTIs), freshness sensors, or RFID-based traceability, to monitor product conditions and keep producers, retailers, and consumers informed about quality throughout the supply chain [

24,

25].

These AIP systems contribute to significant reductions in food waste, a major environmental challenge, while enabling companies to align packaging strategies with circular economy principles. They also promote value creation through improved inventory management, enhanced consumer trust, and potential cost savings in logistics and spoilage prevention [

25,

26].

According to a review by Zuo et al. [

27], several aspiring companies have been on the path towards sustainability over the years, and estimating the environmental impact of the products they sell or the packaging they use is crucial to achieving those goals. Many companies nowadays use these life cycle assessments, commonly called LCAs, as they offer ways to meet companies’ needs in terms of sustainability. LCAs are designed to use reliable science-based data to produce assessments of the possible environmental impacts associated with products, processes, or services. They are tools for analyzing the environmental impacts associated with a product or package over its lifetime, from material sourcing to disposal. However, LCA results depend on the information entered by the practitioner and the assumptions and system boundaries of the LCA model. This means that results are susceptible to bias and vary depending on their use. Companies using LCAs and similar tools can be better equipped to embrace sustainability challenges and assess their impact on their business models and operations, and how they may be reduced [

27].

2.5. Conceptual Model

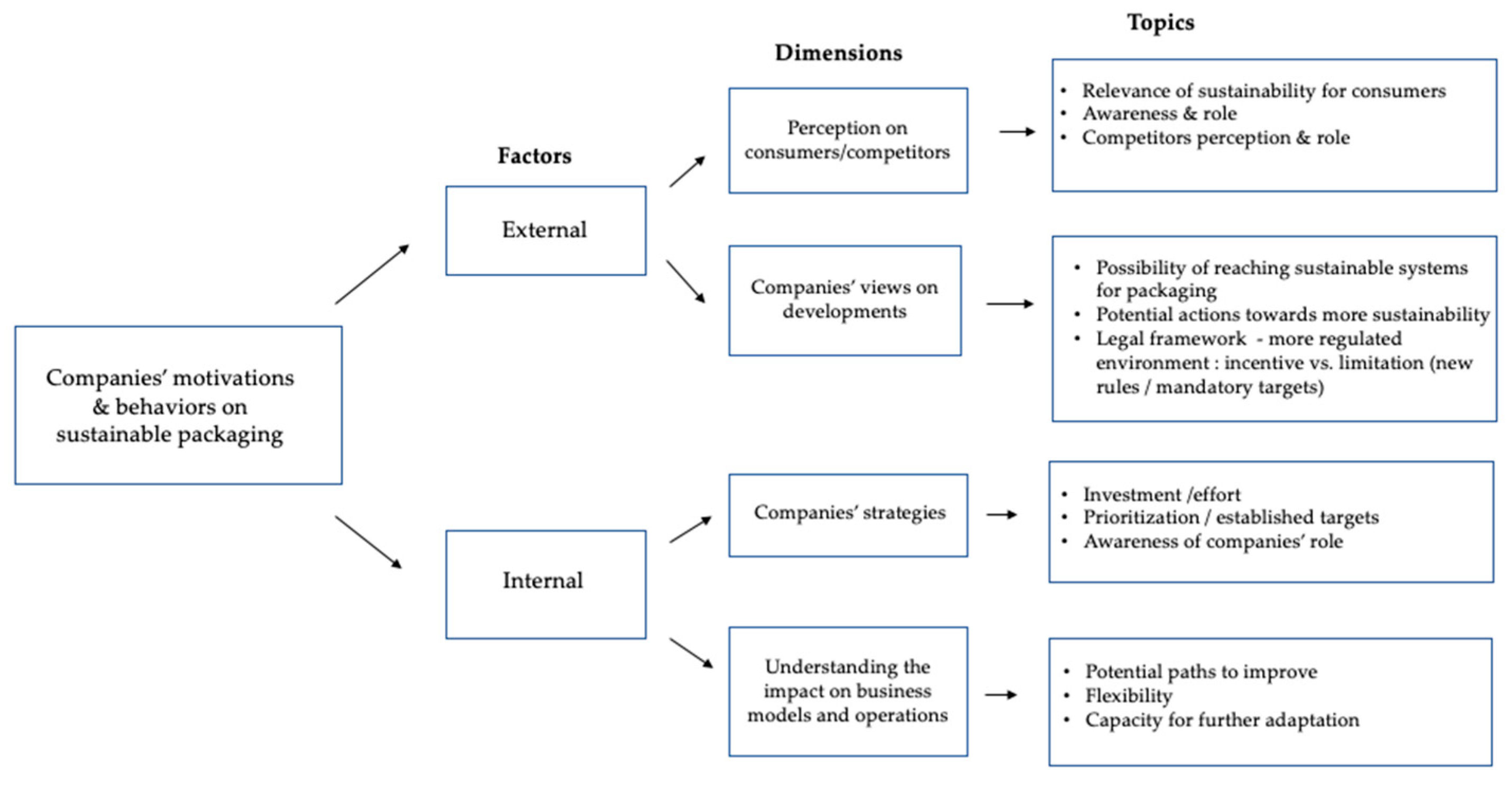

This research aims to help us understand how companies face and integrate sustainability challenges into packaging design, and the motivations and processes behind managers’ decisions when adopting sustainable behaviors, as stated before.

Based on the literature review, a script for the interviews was developed. The interviews aim to show how companies face and integrate sustainable practices and help us understand the motivations for improving companies’ actions, leading to the adoption of more sustainable packaging.

After the literature review, a conceptual model (

Figure 2) was designed, including five dimensions. First, external factors influencing sustainable packaging: The aim is to understand what external factors companies perceive as influencing their actions on sustainable packaging, what the incentives and limitations are, and whether it would be possible to achieve circular systems for packaging.

Second, perceptions of sustainable packaging (consumers/competitors): It is considered relevant for the study to know how companies perceive consumers’ and competitors’ opinions, knowledge, awareness, and role in sustainable packaging, and how the perceptions of consumers and competitors influence companies.

Third, companies’ strategies for sustainable packaging: To understand how internal strategies consider sustainable packaging and how they see it contributing to further improving sustainable packaging.

Fourth, the impact of sustainable packaging on business models and operations: With this dimension, this study intends to collect information on how companies see sustainable packaging impacting their business models and operations, and if they are willing to accommodate further changes.

Fifth, companies’ views on developments in sustainable packaging towards more circular systems: The literature review identified challenges regarding packaging research and supply chains. This dimension intends to help us understand how companies perceive opportunities for further development and to replace any remaining single-use packaging.

Based on the five analytical dimensions previously discussed, we now formulate a conceptual model composed of interrelated propositions. These dimensions are not independent, but interact systemically. For instance, the perceptions of consumer expectations (Dimension 2) mediate the impact of external factors (Dimension 1) on firms’ strategic priorities (Dimension 3). Similarly, the operational implementation of sustainable practices (Dimension 4) reinforces or constrains future innovation paths (Dimension 5). This structure allows researchers to empirically test causal linkages in future studies, contributing to the theoretical advancement of sustainable packaging strategies [

28].

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Approach

According to Aberdeen [

29], a case study “investigates a contemporary phenomenon (the “case”) in depth and within its real-world context, especially when the boundaries between phenomenon and context may not be evident”, which “allows to focus on a “case” and retain a holistic and real-world perspective” [

29]. One major advantage of case studies is that they allow for testing theories within the context of “messy real-life situations”, which are not as straightforward as theories typically portray [

30]. Moreover, telling a real story, especially about a well-known company with products and services everyone is familiar with, makes the case study’s presentation and explanation easier for the readers to follow [

30].

A multiple-case research method was implemented to accomplish the primary goal. This approach allows for the confirmation or disconfirmation of the observations made in previous cases; this research is more challenging than a single case study and enables more reliable insights [

31]. Considering the research question, we chose the research method, as it contributed to a more objective, solid, and unbiased outcome. During the case selection, sampling was applied to identify companies that could provide better insights concerning the research question. The cases intentionally addressed leading companies in the Portuguese markets, with the purpose of their usefulness in revealing insights on the investigated dimensions and the relationship between those dimensions.

The selection of the five companies followed a purposive theoretical sampling strategy aimed at maximizing variation across sectors while ensuring relevance to the topic of sustainable packaging. Each firm is a recognized leader in its industry and has demonstrated active commitment to sustainability initiatives at the national and European levels. Although the sample is geographically limited to Portugal, this national context serves as an informative unit of analysis due to its integration within EU regulatory frameworks and its exposure to circular economy directives. Data saturation was assessed throughout the process, and thematic convergence was achieved after the fifth interview, consistent with established qualitative research norms [

32,

33].

This approach allows us to formulate theoretical propositions. The interview protocol was defined based on the dimensions derived from the literature review. The choice of companies enables the identification of differences regarding their sectors of activity, while still within the same country, thus considering the same political and national context variables.

This study adopts a qualitative approach to develop the research work and understand companies’ motivations when adopting sustainable packaging. Gioia et al. [

34] state that qualitative findings can offer sound guidance in developing emergent concepts into measurable dimensions and that qualitative research can and should stand independently. According to Gioia et al. [

34], qualitative research has a significant benefit: flexibility in applying different approaches to fit varying phenomenological needs.

Gioia et al. [

34] summarized a systematic approach to developing new concepts and articulating grounded theory to bring qualitative rigor to conducting and presenting inductive research. Concepts are viewed as precursors to dimensions in understanding organizational worlds. Dimensions are abstract theoretical formulations concerning phenomena of interest [

35,

36,

37]. Thus, dimensions outline a domain of attributes that can be operationalized and preferably quantified as variables.

This study involved interviews with managers and decision-makers from companies regarding sustainable packaging, all experts in their respective fields. Every interviewee was willing to participate in the study and provided essential information. The interviews were structured according to the study’s dimensions and the literature review, with scripts tailored to each industry.

The university’s ethics committee was not formally consulted for this study because institutional policy exempts research involving only interviews with adult participants from ethical review if participation is voluntary and data confidentiality is maintained. This study was designed and carried out in strict accordance with these institutional guidelines. All participants were adults who freely consented to participate, and no personally identifiable information was collected at any point, ensuring complete anonymity and the protection of participant confidentiality.

3.2. Design of the Interviews

The interviews were prepared based on a list of questions derived from the five dimensions identified in the conceptual model and the topics extracted from the dimensions presented. The topics serve as a basis for the questions in the interview protocol presented in the

Appendix A. Therefore, the conceptual model presented before resulted in theoretical formulations about the topic of interest [

34], which aims to help us understand how companies face and integrate sustainability challenges in packaging design. The goal is to determine whether external and internal factors are integrated into sustainable packaging design and the motivations and processes behind managers’ decisions when adopting sustainable behaviors (

Table 2).

The full interview protocol is provided in

Appendix A.1. The average duration of each interview was approximately 55 min, enabling in-depth discussion across the five core thematic dimensions [

34,

38].

3.3. Data Collection

Theoretical sampling was utilized during the case selection process. Recommended by Eisenhardt & Graebner [

33] for exploratory research, theoretical sampling involves a purposeful selection of cases that can reveal relationships between the studied dimensions, enabling the researcher to make findings based on generalizations and theoretical propositions rather than statistical relationships [

29]. To ensure case diversity, as suggested by Flick [

39], all informants were selected from different industries and sizes in Portugal, providing a variety of experiences in the market industry.

The five companies that were interviewed were chosen considering factors such as their diversity in terms of the business sector, diversity of packaging needs, business models, and markets. They are all relevant players in their respective market share and are concerned with environmental sustainability and innovation. For confidentiality purposes, the companies are referred to as Company A, Company B, Company C, Company D, and Company E. These firms were chosen due to their relevance in the Portuguese market, particularly concerning their sector and market share. They operate in different sectors and have unique requirements for packaging and branding. These companies also have different business models and target markets. Additionally, they prioritize environmental sustainability and innovation, with dedicated teams in these areas. As a result, they are leaders in environmental sustainability, including packaging, and represent the best practices in their respective sectors in Portugal (

Table 3).

Company A is the largest cork transformation group worldwide, contributing as a major player to the business, market, economy, innovation, and sustainability of the whole cork industry.

Company B is a leading Portuguese beer brand originally launched in 1927, and it occupies a reference position in the beer market, being among the preferred beer brands of the Portuguese. It is also the most sold Portuguese beer in the world. The company includes the sustainable distribution of beverages through kegs, recyclable glass bottles, and cans that are single-use, which was a reason for choosing them for this study.

Company C began its operations over five decades ago and has since evolved into a multinational corporation managing a diversified portfolio of businesses. Its activities span across retail, financial services, technology, real estate, and telecommunications, reflecting a complex business model and a broad market presence that justified its inclusion in this study.

Company D is a group comprising several of the leading companies in the Portuguese agro-industrial sector. With production units and facilities located across various regions of Portugal, including Trofa, Ovar, Pinheiro de Lafões, São Pedro do Sul, Vouzela, Pinhel, and Torres Novas, the group operates under strong, market-leading brands. It is recognized for its dynamic and innovative approach to business and its clear commitment to social and environmental responsibility, both nationally and internationally.

Company E is a Portuguese dairy manufacturer established in 1996 through the merger of several key cooperative groups in the sector. Due to the nature of its products, the company is required to comply with rigorous food safety and quality standards. It focuses on delivering high-quality products and developing innovations that respond to evolving consumer needs, while also maintaining a strong commitment to sustainability and responsible packaging practices.

4. Results

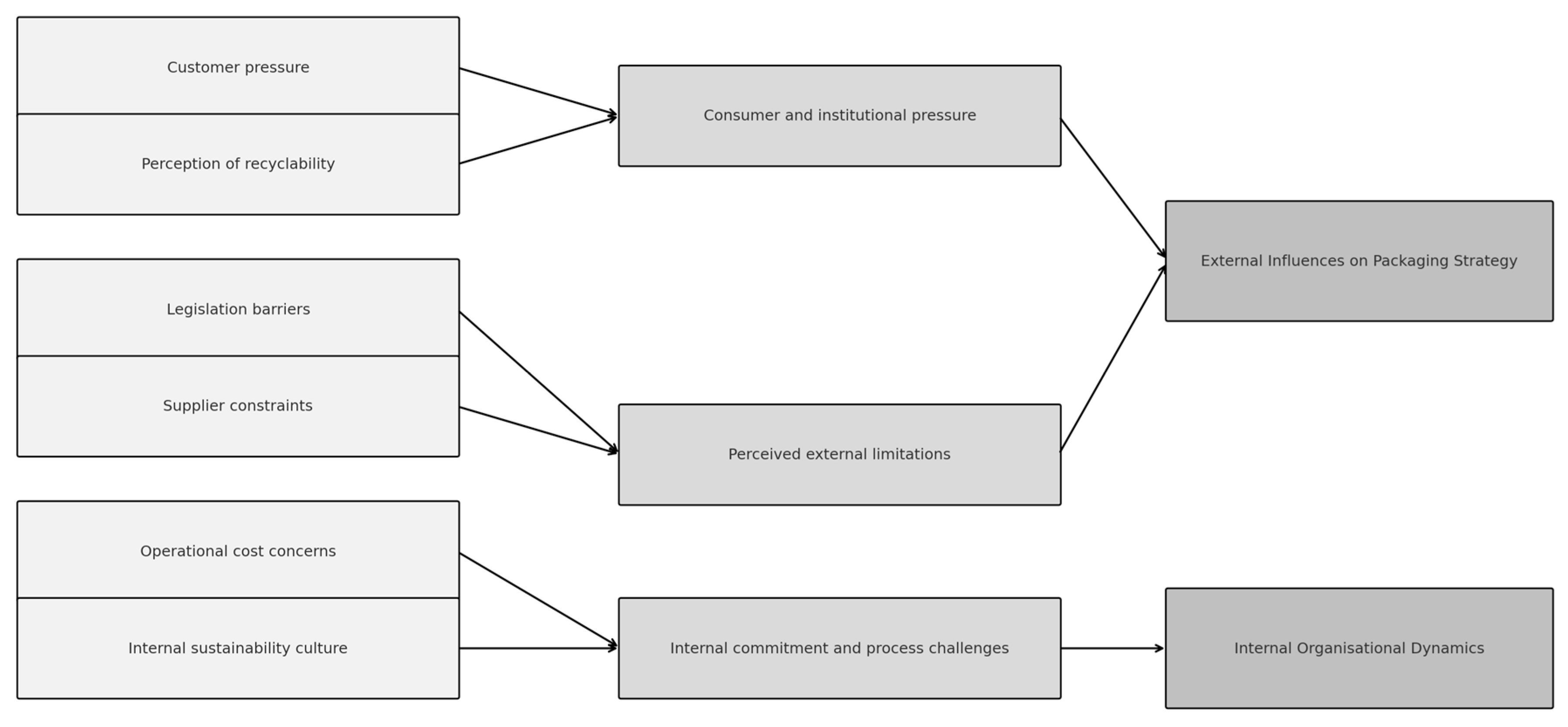

The analysis followed Gioia’s inductive methodology [

24], allowing for the emergence of structured theoretical insights from empirical data. First-order concepts were derived from the interviews, grouped into second-order themes, and synthesized into five aggregate dimensions.

Figure 3 illustrates the data structure according to Gioia et al.’s [

34] inductive logic, offering transparency regarding the coding process and theoretical abstraction.

Data analysis shows that several issues influence companies’ actions and decisions when implementing sustainability in packaging. Among these issues, some are beyond the control of companies, but could be integrated into their strategies to facilitate and promote greater sustainability in packaging. As the research progresses, we identify similarities and differences among the various categories. This process reduces the categories to a more manageable number, allowing us to relate interview data to the theoretical samples [

34].

External and internal factors influence how companies confront and integrate sustainability challenges into packaging design and the motivations and processes behind managers’ decisions in adopting sustainable behaviors. The interviews indicate that while the five companies are committed to environmental sustainability in packaging, their main priorities remain their business objectives, safety, quality, and the experience they want to provide to their consumers. Sustainability and environmental concerns are considered factors that must fit into this equation. For example, companies B, C, and D emphasized preserving the product safely and securely while conveying a high-quality experience to consumers.

4.1. External Factors

4.1.1. Perceptions of Consumers and Competitors

Regarding the perceptions of competitors and consumers of environmental sustainability in packaging, the five companies believe that it plays a role, but not as importantly as the literature predicts. For instance, a representative from Company A noted that consumer perception is more closely linked to consumers’ trust in the brand. Similarly, at Company E, price is viewed as a more decisive factor, since eco-design often increases production costs and, consequently, the product’s final price. Representatives from Companies B, C, and D expressed that when consumers make purchasing decisions based on sustainability, those decisions are often influenced by subjective interpretations rather than scientific evidence. One manager from Company C observed, “Consumers may assume that certain materials, such as bioplastics or glass bottles, are recyclable, which may not always be the case…”. Although consumer perception is acknowledged as relevant, it is generally viewed as insufficiently informed or based on misconceptions about environmental sustainability in packaging.

Furthermore, Company C highlighted that, after a single-use packaged product is sold and the company has paid the respective tax (such as the Ponto Verde contribution), the responsibility for proper disposal shifts to the consumer. It is therefore up to the consumer to ensure that packaging waste is correctly sorted for recycling or incineration.

In response to this challenge, Companies B, C, and D have implemented awareness campaigns to educate consumers on how to dispose of packaging waste responsibly and have included informative messages on their packaging. While all five companies recognize and respond positively to competitors’ sustainability efforts, one representative from Company B noted that competition drives innovation, stating “Companies like us are always trying to be better than our biggest competitor, that is what motivates us to do better each day…”. Additionally, Company D pointed to the structural limitations of the packaging market that affect not only their strategies, but also those of their competitors.

4.1.2. Legislative Framework

Guillard et al. [

15] argued that the legal framework is seen as a motivation or limitation. The legal framework is seen only as a limitation for the five companies, particularly for companies that have already invested significant capital and resources in sustainability. Company E is under a strong sense of pressure to comply with government regulations continuously. However, the company does not view the legal framework as a source of motivation. As one representative from Company E explained, “If we were rewarded for making more and even better things to implement sustainable practices, we (companies) would do it with pleasure, but instead, we are worried about the fines we might have to pay if something is not right for some reason…”. This sentiment reflects a broader perception that regulatory compliance is driven more by fear of penalties than by encouraging or recognizing proactive environmental efforts.

4.1.3. Companies’ Views on a Future with More Sustainable Packaging

The five companies agree on a more favorable future for packaging, but that is not yet a reality, and they continue to work to the best of their ability. Companies are concerned about brands, support eco-design, and have introduced valuable circular systems to enable reuse in certain areas. For Company B, implementing a reusable barrel system has significantly reduced the company’s carbon footprint, and recycling practices are adopted whenever feasible. Nonetheless, there remains an urgent need to increase the recyclability of packaging and reduce the reliance on virgin materials in producing new packaging, particularly bottles. In the case of Company C, particularly within its retail operations, there are still certain types of packaging in circulation that are not currently recyclable. As one representative from Company C noted, “Not all the material is recyclable as everyone thinks it is, for example, glass, not every glass can be recycled”. This highlights ongoing challenges related to material selection and consumer misconceptions regarding the recyclability of packaging.

4.2. Internal Factors

4.2.1. Companies’ Strategies for Adopting Sustainable Packaging

All five companies have strategies for environmental sustainability in packaging, with clear internal targets in a circular environmental system. These are mostly built upon targets defined under their associations with organizations that promote environmental sustainability and impose internal targets resulting from their companies’ engagements with those organizations. Company C is a member of the Ellen MacArthur Foundation and has introduced guidelines to produce the products marketed under their brand, following those commitments. Company B also refers to its international commitments. Company D emphasizes its partnership with a non-profit organization. Companies B, C, and D have declared themselves active players in promoting environmental sustainability. The five companies recognize the impact of sustainability on business models and operations and are willing to adapt. Company C mentioned its pilot project on reuse, Company D referred to eco-design, and Company E highlighted the maximization of reuse as a pathway forward.

4.2.2. Results of the Impact of Sustainable Packaging on Business Models and Operations

The companies interviewed invest in sustainability and have qualified teams working to implement the best approaches and practices that match their businesses. For example, a representative from Company A leads a Systems and Improvements team that oversees “ensuring the quality of our products is key, be aware of what we can and cannot do too…”, which will allow for a more predictable impact on business models and operations. The experience they want to convey to consumers aligns with their internal business objectives, safety, and quality. Sustainability and environmental responsibility are regarded as critical elements that companies must consider. With their expertise in sustainability, companies have implemented packaging systems that reduce single use, promote reuse, and incorporate eco-design while conveying their brand messages. When asked about using life cycle assessments (LCAs), only Company C and D stated that they use them to manage the environmental impact of the products they sell or the packaging they utilize.

The five companies have already defined internal targets for environmental sustainability in packaging, aligning with their organizational commitments to sustainability. They have introduced guidelines and practices to support these commitments. Business models and operations have been modified to incorporate more sustainable packaging. While the companies have circular economy systems in place, they do not have a fully circular system that encompasses all their packaging and waste, and achieving this may not be feasible in the short term. The companies have also recognized that not all their packaging will be recyclable soon. They comply with applicable legislation but view additional revised legislation and targets as limitations. Although they meet the legal requirements for packaging and waste management, they have not yet achieved a circular economy system for packaging.

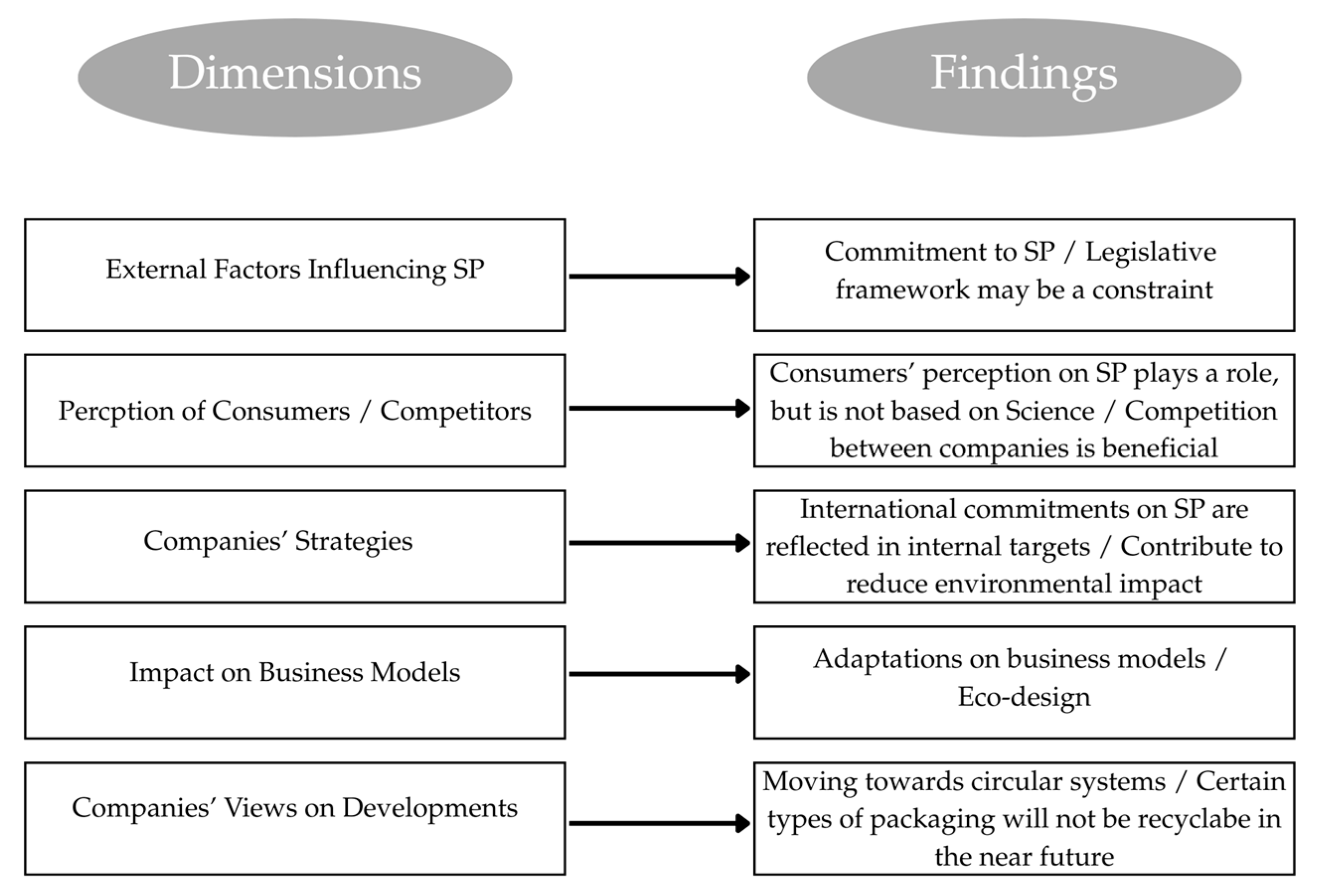

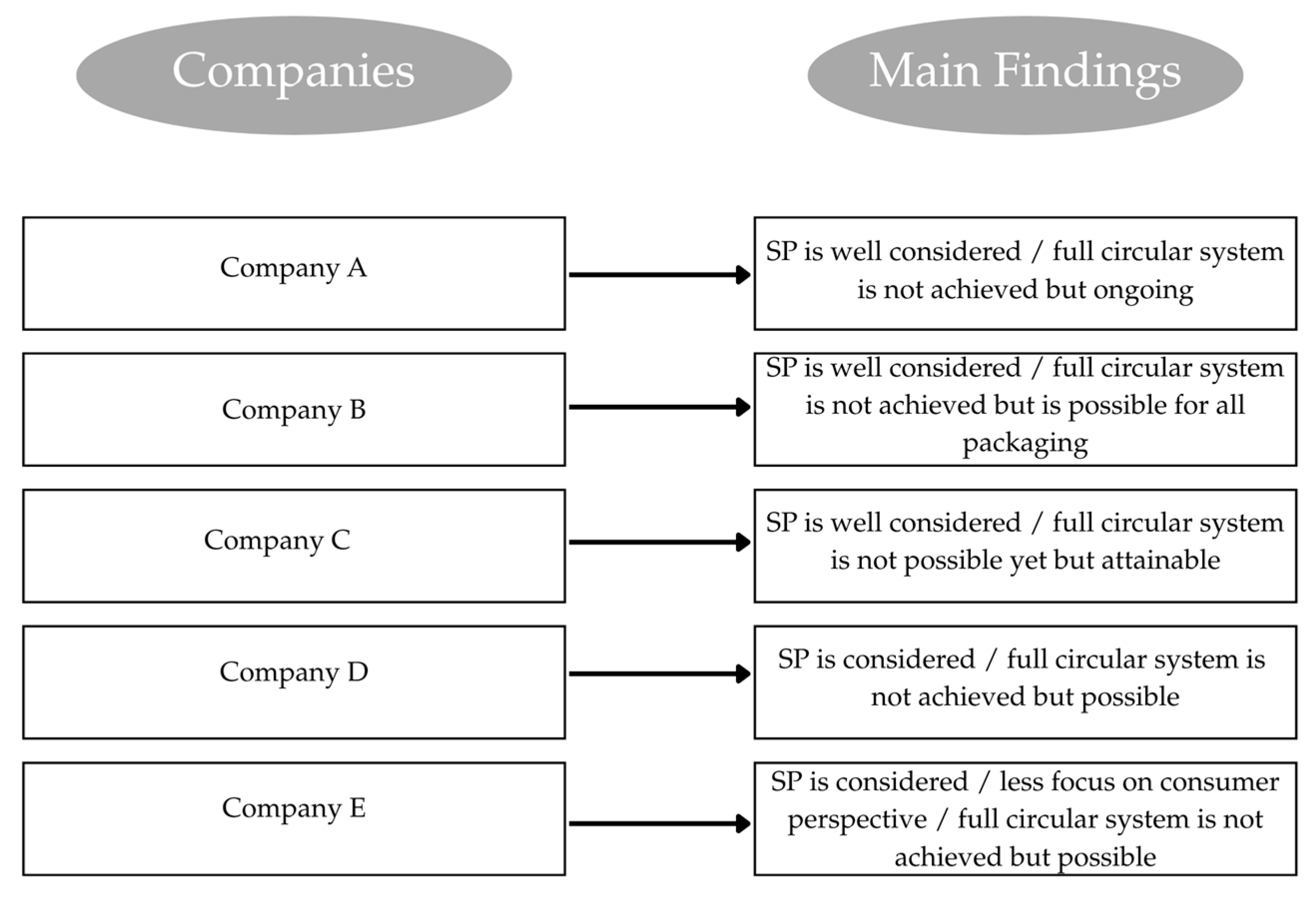

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 summarize the main findings by dimension and company, and

Table 4 provides a detailed summary of the global findings.

5. Discussion

First, companies must use transport packaging to protect the product and ensure tertiary packaging sustainability within the three levels described by Rezaei et al. [

6]. To achieve this, companies depend on other industries, particularly the packaging industry, to offer materials that can be fully recycled or reused across all three levels of packaging at an affordable price. The findings show that companies’ packaging decisions are influenced by a complex mix of market demands, technological constraints, and regulatory pressures. From an institutional theory perspective, companies’ responses to sustainable packaging can be seen as reactions to coercive pressures (e.g., EU legislation), mimetic pressures (e.g., copying industry leaders), and normative pressures (e.g., stakeholder expectations). At the same time, the resource-based view (RBV) suggests that firms regard sustainability-oriented capabilities, such as eco-design, closed-loop systems, and LCA expertise, as potential sources of long-term competitive advantage differentiation. In this context, the interviews show that Companies B, C, D, and E have emphasized the need to protect their products and maintain quality. No other recyclable or reusable alternatives can offer consumers the same protection, quality, and reliability for transportation purposes. Company D pointed out that competitors face similar obstacles. Company C mentioned the difficulty of reducing packaging for products such as yogurts and tertiary packaging.

Consumer perception is one issue that does not rely on companies’ decisions regarding packaging. Boz et al. [

2] stated that consumers have become increasingly familiar with sustainable packaging. Consequently, companies and policymakers have acknowledged the necessity to respond to the growing demand for sustainability initiatives. Examining the attainability of such a path within sustainable packaging indicates that companies must confront the challenge of environmental sustainability.

Consistent with Zhang & Yang [

8], several companies emphasized the role of packaging esthetics in preserving brand identity, even when facing sustainability trade-offs. However, companies emphasize the lack of knowledge surrounding the choice of sustainable products and how packaging should be disposed of for recycling, reuse, or waste processing. Companies could benefit from selecting products with eco-friendly packaging and making informed choices, which may positively impact the environment. While consumers’ choices are independent of companies’ decisions, all companies implement internal strategies to promote awareness campaigns that explain the environmental impact of various materials and the advantages of choosing more sustainable options. They also include clear messages on labels to inform consumers. In this context, sustainability could serve a market purpose and be regarded as another customer requirement within companies, in line with Rezaei et al. [

6].

Legal requirements constitute another independent issue in companies’ decisions; they come with commitments to targets and deadlines for achieving sustainable packaging. Therefore, the next step in pursuing sustainable packaging is to consider, at the initial stage of their expansion, all consumer, market, and legal obligations that the materials must meet [

15]. A new paradigm aims to advance environmental sustainability in packaging by creating complete circular systems by 2030, but these targets may have varying impacts on companies’ business models. A new paradigm with mandatory targets should introduce new challenges for companies under economic pressure. Firms are learning about recyclability, the responsibility of packaging in enhancing product protection and operational efficiency, and the various supply chain challenges associated with moving away from single-use packaging. Although targeted dates have not been met, many advancements have occurred in this field, such as the growth of refillable pilots and retailers sharing their insights, the use of fiber (paper)-based packaging in food packaging, and innovations like paper bottles for liquids.

Nonetheless, many companies face technical challenges in achieving goals such as having 100% recyclable packaging and eliminating reliance on virgin plastics. For some, scaling pilots remains out of reach. Companies exhibit a broad spectrum of compliance, which complicates attaining specific goals. The complexities of manufacturing infrastructure, recycling infrastructure, recycling technologies, product protection, regulations, and end markets for recycled materials hinder some companies and products from achieving their objectives. Additionally, the lack of recycling infrastructure is viewed as an obstacle.

A more regulated environment, independent of companies’ decisions, could help clarify specific goals related to complying with mandatory requirements to achieve a circular system for environmental sustainability in packaging. It may not be realistic for companies to comply with them soon, as they already set similar targets in their internal decisions that they could not attain. Having adequate legal incentives might help facilitate progress.

Packaging supports and promotes improvements and innovations in the sustainable management of supply chains [

3]. Guillard et al. [

15] stated that Europe has been heavily investing in research for new developments in packaging technologies and is perceived as a robust market with immense potential demand. Therefore, adopting a novel approach to economic development models for countries and corporate operations that prioritize economic and environmental rationality in choosing sustainable packaging is imperative. This calls for developing a sustainable economic model that prioritizes ecological principles and benefits everyone rather than simply satisfying the market. Although the lack of alternative packaging options does not depend on companies’ decisions, sustainability strategies could include incentives for companies to collaborate with universities and research institutions to explore new materials that could be sustainable and meet the required standards and experience.

Companies’ strategies may also contribute to addressing the shortage of materials due to the limited availability of natural resources, as Leitão [

40] referred to. However, many sustainable packaging solutions that do not meet favorable economic and time parameters are not implemented, as van Birgelen et al. [

9] noted. Company E, in the interview, stated the importance of using life cycle assessments (LCAs). LCAs are tools for analyzing environmental impacts associated with a product or package over its lifetime [

27]. The shortage of materials could be addressed by creating closed loops with packaging suppliers’ systems, where materials are recycled and reused rather than discarded after a single use. Company B, for instance, explained that it uses recycled materials in a closed loop. However, it also uses other recycled packaging made partially of recycled material and partially of virgin material. Therefore, companies may have opportunities for improvement in this respect.

6. Conclusions

The primary objective of this study was to examine how companies confront and incorporate sustainability challenges in packaging design, along with the processes and motivations that influence managers’ decisions when embracing sustainable practices.

Some external factors prevent companies from transitioning to fully sustainable packaging soon. These obstacles appear across the industry in the same markets and hinder the achievement of sustainable packaging goals. Despite efforts from companies, a substantial amount of packaging that is not recyclable still contributes to tons of non-recyclable waste. Waste levels are rising considerably with increased consumption, necessitating more effort from companies to attain environmental sustainability in packaging that conserves resources for future generations. Currently, the regular use of virgin materials continues, while the use of recycled materials remains limited due to supply shortages. Additionally, further secondary markets for materials must be developed, and markets for waste management must be cultivated.

Companies must harmonize rules and address the remaining obstacles to reduce negative environmental impacts. This will involve pushing for innovation in packaging design and opening the market for secondary materials, resulting in reduced gas emissions, increased resource efficiency, and decreased water, soil, and air pollution. Environmental sustainability in packaging may effectively contribute to progress. Many changes are being made in this regard. However, this study shows that based on the five interviews conducted, each company (A, B, C, D, and E) demonstrated what they believe to be their best effort in achieving more sustainable packaging in the path ahead. They understand how essential sustainability is nowadays.

From a theoretical perspective, data analysis reveals that several factors impact companies’ actions and decisions regarding implementing sustainability in packaging. Some of these factors are beyond companies’ direct control; however, they could be incorporated into their strategies or decisions to promote and facilitate greater sustainability in packaging. This study presents the current situation regarding information collected from five companies relevant to their sector and market share. They are advanced in sustainable packaging, and almost all are still implementing measures to achieve even more sustainable packaging. Additionally, this research aims to provide valuable insights for other studies and companies poised for change, potentially contributing to companies’ internal assessments of the impact of a new paradigm on sustainable packaging. At the managerial level, companies could further explore other actions and opportunities within their strategies and business models to promote greater sustainability and address issues such as material shortages, through supporting research on potential new materials and packaging methods, or by communicating their brand message differently through packaging. Although companies have made significant investments and efforts towards more sustainable packaging, they recognize the need to clarify specific requirements in the current legislative framework. They have legal incentives, but fear potential limitations in future revisions.

Limitations and Future Research

Considering that this study primarily aims to understand how companies confront and integrate sustainability challenges in packaging design and the motivations and processes influencing managers’ decisions when adopting sustainable behaviors, it would have been insightful to interview a company that produces its packaging rather than merely purchasing it from a supplier; this would provide a much deeper insight into the study undertaken here. Additionally, a limitation worth noting is that all interviews were conducted with Portuguese companies. Although Portugal offers a representative EU context for sustainable packaging because of its regulatory alignment and industrial diversity, future research could examine whether similar patterns occur in other cultural and economic settings, such as North America or the Asia-Pacific regions.

It would be fascinating to study how artificial intelligence can influence the development and production of packaging and its sustainability. There may be new tools in the future that can be employed in packaging design, such as emerging technologies like blockchain and artificial intelligence, to enhance supply chains and minimize waste in packaging production and distribution.

Additionally, future research could focus on developing consumer education campaigns that raise awareness about sustainable packaging and encourage more environmentally conscious purchasing decisions. By informing consumers about the environmental impact of their choices, companies can help shift consumer behavior towards more sustainable options, which is beneficial for them. Moreover, measuring how the use of LCAs (or LCA-type approaches) helps companies better address upcoming challenges related to sustainability could be interesting and may influence their motivations for adopting sustainable packaging, based on Zuo et al. [

27].

Finally, future research would benefit from methodological triangulation to strengthen the robustness and validity of findings. While this study focused solely on in-depth interviews with managers to explore internal perceptions and decision-making processes, additional sources of data (such as documentary evidence, sustainability reports, packaging lifecycle data, direct observation, and consumer data) could offer a more comprehensive and externally validated understanding of how sustainable packaging strategies are developed and executed. This triangulated approach would enable researchers to compare stated intentions with actual outcome practices.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.D., S.C.S. and M.I.R.; methodology, P.D., S.C.S. and M.I.R.; software, P.D., S.C.S. and M.I.R.; validation, P.D., S.C.S. and M.I.R.; formal analysis, P.D., S.C.S., and M.I.R.; investigation, P.D., S.C.S. and M.I.R.; resources, P.D., S.C.S., and M.I.R.; data curation, P.D., S.C.S., and M.I.R.; writing—original draft preparation, P.D., S.C.S., M.I.R., R.P. and A.E.; writing—review and editing, P.D., S.C.S., M.I.R., R.P. and A.E.; visualization, P.D., S.C.S., M.I.R., R.P. and A.E.; supervision, P.D. and S.C.S.; project administration, P.D., S.C.S., M.I.R., R.P. and A.E.; funding acquisition, P.D., S.C.S., M.I.R., R.P. and A.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable since no personal information was collected; only non-confidential company-level information was gathered.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article. Additional information available upon request.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the author(s) used Grammarly to edit the language under their direct supervision. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| B2B | Business-to-Business |

| EC | European Commission |

| EU | European Union |

| EUROPEN | European Organization for Packaging and the Environment |

| LCA | Life Cycle Assessment |

| NGO | Non-Governmental Organization |

| SP | Sustainable Packaging |

| SPC | Sustainable Packaging Coalition |

| SPA | Sustainable Packaging Alliance |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

Script of the Interview

- (1)

What external factors influence the company in terms of packaging sustainability?

- (i)

E.g., Legal, economic, social, environmental factors, or others.

- (ii)

How can legal regulations constrain the way companies act in the various dimensions of environmental sustainability? And how can other external factors impact brand identity?

E.g., Limitations arising from current legislation.

- (2)

How important are consumers’ and competitors’ perceptions of packaging in achieving environmental sustainability goals?

- (i)

How do you receive this feedback? Do you believe consumers are sensitive to environmental sustainability? And do you think this is a differentiating factor when choosing a product?

E.g., Through surveys, the marketing department…

- (3)

What is the company’s strategy regarding environmental sustainability? In which areas of the company do you believe it should be reflected? And what is the strategy specifically for packaging? Are there defined goals in this area?

- (i)

Is it the company’s policy to stay up to date with environmental sustainability today and with the impact that sustainable packaging can have on consumer perception at the time of purchase?

- (ii)

How is packaging waste managed by your company?

E.g., Recycling, incineration.

- (4)

In what way does environmental sustainability affect your company’s business model? And how is this reflected in the packaging design? What challenges have you encountered in the operational implementation of environmental sustainability?

- (i)

When defining how the product will be packaged, is environmental sustainability considered in the design?

- (ii)

Has your packaging changed over the years? If so, why did you feel the need to change it? For reasons of brand identity/environmental sustainability/production cost?

- (iii)

What identifying features can you not give up when defining a package?

- (5)

Do you think a circular economy for packaging is possible soon?

- (i)

How do you align in this area with what is being done in other countries?

E.g., Association of company representatives at the national or international level.

- (ii)

Within the legal framework, if the new EU legislation is approved, what will be the impact in terms of brand identity? And what will be the impact for the company?

- (iii)

What advice would you give to small companies in the same field that are just starting, to meet the challenge of environmental sustainability in packaging design?

E.g., Recycling, waste reduction, or others.

- (iv)

Do you think this is the most appropriate approach to environmental sustainability?

References

- United Nations. Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Note/by the Secretary-General. Available online: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/139811?v=pdf (accessed on 19 May 2025).

- Boz, Z.; Korhonen, V.; Sand, C.K. Consumer Considerations for the Implementation of Sustainable Packaging: A Review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Arca, J.; González-Portela Garrido, A.T.; Prado-Prado, J.C. “Sustainable packaging logistics”. The link between Sustainability and Competitiveness in Supply Chains. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, S.L.; Kelly, F.J. Plastic and Human Health: A Micro Issue? Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 6634–6647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, R.C.; Courtene-Jones, W.; Boucher, J.; Pahl, S.; Raubenheimer, K.; Koelmans, A.A. Twenty years of microplastic pollution research—What have we learned? Science 2024, 386, 6720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, J.; Papakonstantinou, A.; Tavasszy, L.; Pesch, U.; Kana, A. Sustainable product-package design in a food supply chain: A multi-criteria life cycle approach. Packag. Technol. Sci. 2019, 32, 85–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rundh, B. Linking packaging to marketing: How packaging is influencing the marketing strategy. Br. Food J. 2013, 115, 1547–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Yang, Z. Research on the Correlation Between Marketing and Product Packaging Design. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Financial Innovation and Economic Development (ICFIED 2021), Online, 22 March 2021; pp. 604–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Birgelen, M.; Semeijn, J.; Keicher, M. Packaging and Proenvironmental Consumption Behavior. Environ. Behav. 2009, 41, 125–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bech-Larsen, T. Danish Consumers’ attitudes to the functional and environmental characteristics of food packaging. J. Consum. Policy 1996, 19, 339–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlegelmilch, B.B.; Bohlen, G.M.; Diamantopoulos, A. The link between green purchasing decisions and measures of environmental consciousness. Eur. J. Mark. 1996, 30, 35–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Shaughnessy, J.; O’Shaughnessy, N.J. Marketing, the consumer society and hedonism. Eur. J. Mark. 2002, 36, 524–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Torre, P.L.; Adenso-Diaz, B.; Artiba, H. Environmental and reverse logistics policies in European bottling and packaging firms. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2004, 88, 95–104. Available online: https://ideas.repec.org/a/eee/proeco/v88y2004i1p95-104.html (accessed on 19 May 2025). [CrossRef]

- de Koeijer, B.; de Lange, J.; Wever, R. Desired, Perceived, and Achieved Sustainability: Trade-Offs in Strategic and Operational Packaging Development. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillard, V.; Gaucel, S.; Fornaciari, C.; Angellier-Coussy, H.; Buche, P.; Gontard, N. The Next Generation of Sustainable Food Packaging to Preserve Our Environment in a Circular Economy Context. Front. Nutr. 2018, 5, 412270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regulation-1935/2004-EN-EUR-Lex. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32004R1935 (accessed on 8 July 2025).

- Ali, S.S.; Abdelkarim, E.A.; Elsamahy, T.; Al-Tohamy, R.; Li, F.; Kornaros, M.; Zuorro, A.; Zhu, D.; Sun, J. Bioplastic production in terms of life cycle assessment: A state-of-the-art review. Environ. Sci. Ecotechnology 2023, 15, 100254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senila, L.; Kovacs, E.; Resz, M.A.; Senila, M.; Becze, A.; Roman, C. Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) of Bioplastics Production from Lignocellulosic Waste (Study Case: PLA and PHB). Polymers 2024, 16, 3330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behind the Barrier: Complex Reality of Paper and Board Packaging Functionalization | Food Packaging Forum. Available online: https://foodpackagingforum.org/news/behind-the-barrier-complex-reality-of-paper-and-board-packaging-functionalization?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 8 July 2025).

- Gavronski, I. Resources and Capabilities for Sustainable Operations Strategy. J. Oper. Supply Chain. Manag. 2012, 5, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todorova, G.; Durisin, B. Absorptive capacity: Valuing a reconceptualization. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 774–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmer, K.; Fröhling, M.; Schultmann, F. Sustainable supplier management—a review of models supporting sustainable supplier selection, monitoring and development. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2016, 54, 1412–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Sarkis, J. Integrating Strategic Carbon Management into Formal Evaluation of Environmental Supplier Development Programs. Bus Strategy Environ. 2015, 24, 873–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Realini, C.E.; Marcos, B. Active and intelligent packaging systems for a modern society. Meat Sci. 2014, 98, 404–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biji, K.B.; Ravishankar, C.N.; Mohan, C.O.; Gopal, T.K.S. Smart packaging systems for food applications: A review. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 52, 6125–6135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Abreu, D.A.P.; Cruz, J.M.; Losada, P.P. Active and Intelligent Packaging for the Food Industry. Food Rev. Int. 2012, 28, 146–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, J.; Pullen, S.; Rameezdeen, R.; Bennetts, H.; Wang, Y.; Mao, G.; Zhou, Z.; Du, H.; Duan, H. Green building evaluation from a life-cycle perspective in Australia: A critical review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 70, 358–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, S.; Vladimirova, D.; Holgado, M.; Van Fossen, K.; Yang, M.; Silva, E.A.; Barlow, C.Y. Business Model Innovation for Sustainability: Towards a Unified Perspective for Creation of Sustainable Business Models. Bus Strategy Environ. 2017, 26, 597–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aberdeen, T.; Yin, R.K. Case study research: Design and methods. Can. J. Action Res. 2013, 14, 69–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, M.D. Qualitative Research in Business & Management. Qual. Res. Account. Manag. 2009, 6, 292–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourgeois, I.L.J.; Eisenhardt, K.M. Strategic Decision Processes in High Velocity Environments: Four Cases in the Microcomputer Industry. Manag. Sci. 1988, 34, 816–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, G.; Bunce, A.; Johnson, L. How Many Interviews Are Enough? An Experiment with Data Saturation and Variability. Field Methods 2006, 18, 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K.M.; Graebner, M.E. Theory Building from Cases: Opportunities and Challenges. Source Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gioia, D.A.; Corley, K.G.; Hamilton, A.L. Seeking Qualitative Rigor in Inductive Research. Organ. Res. Methods 2013, 16, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J.R.; Bagozzi, R.P. On the nature and direction of relationships between constructs and measures. Psychol. Methods 2000, 5, 155–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofmann, D.A.; Morgeson, F.P. Safety-related behavior as a social exchange: The role of perceived organizational support and leader-member exchange. J. Appl. Psychol. 1999, 84, 286–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellocchio, A.; Brininger, A.; Phillips, G.; Sharp, D.; Sheridan, M. Design Space of a Tactical, Air-Launched Balloon. ASME Int. Mech. Eng. Congr. Expo. 2014, 88612, V003T05A001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracy, S.J. Qualitative quality: Eight “big-tent” criteria for excellent qualitative research. Qual. Inq. 2010, 16, 837–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flick, U. The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Data Analysis; Sage Publications, Inc.: London, UK, 2014; pp. 1–664. Available online: https://sk.sagepub.com/hnbk/edvol/the-sage-handbook-of-qualitative-data-analysis/toc (accessed on 8 July 2025).

- Leitão, A. Economia circular: Uma nova filosofia de gestão para o séc. XXI. Port. J. Financ. Manag. Account. 2015, 1, 149–171. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10400.14/21110 (accessed on 19 May 2025).

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).