Influences of Product Environmental Information on Consumers’ Purchase Choices: Product Categories Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

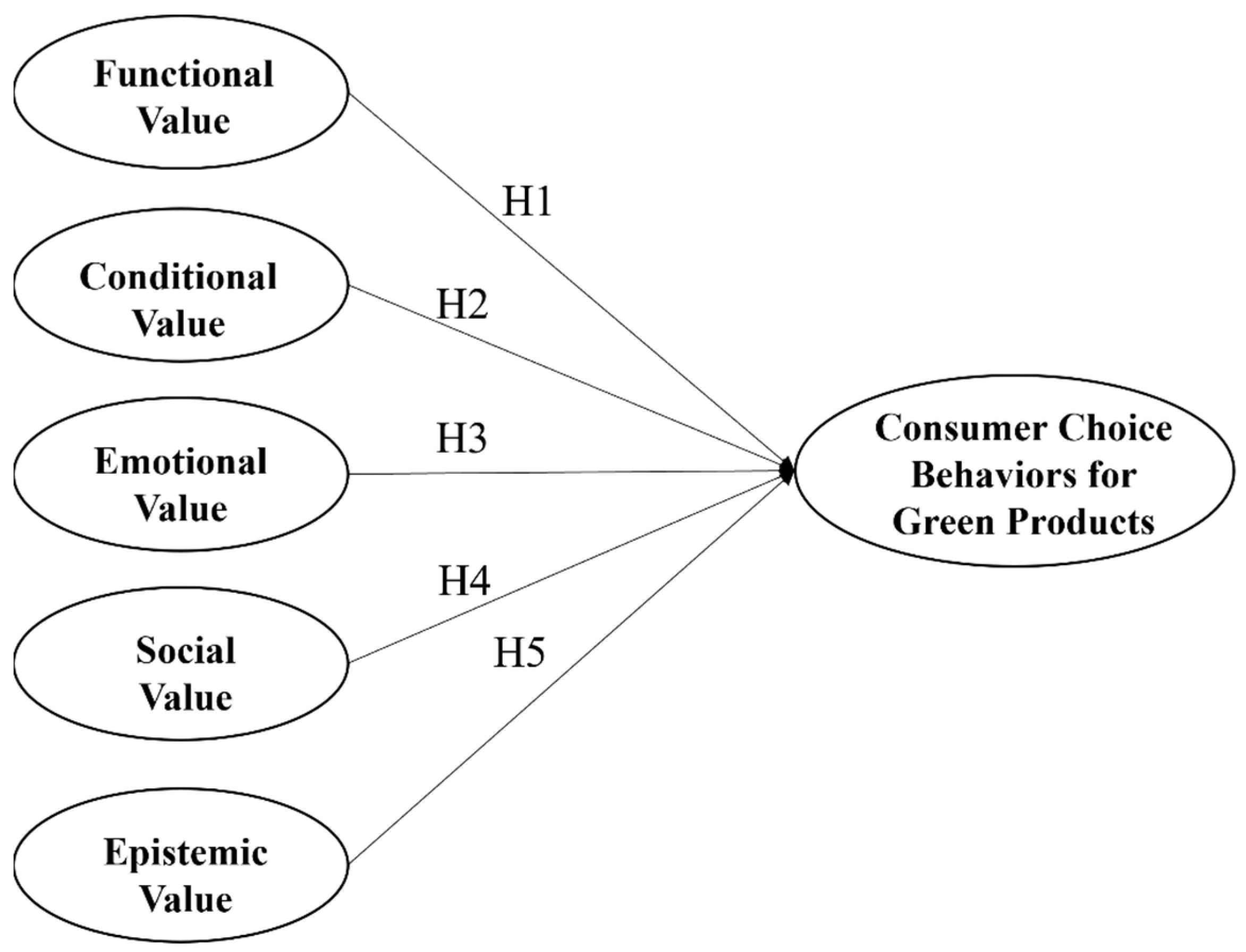

2. Theory Foundation and Hypotheses

2.1. Theory of Consumption Values

2.2. Different Influencing Factors Across Product Types

2.3. Mediating Effect of Consumption Values

3. Research Methods

3.1. Questionnaire Design

3.2. Data Acquisition and Quality Control

3.3. Respondents’ Information

3.4. Model Reliability and Validity

4. Results

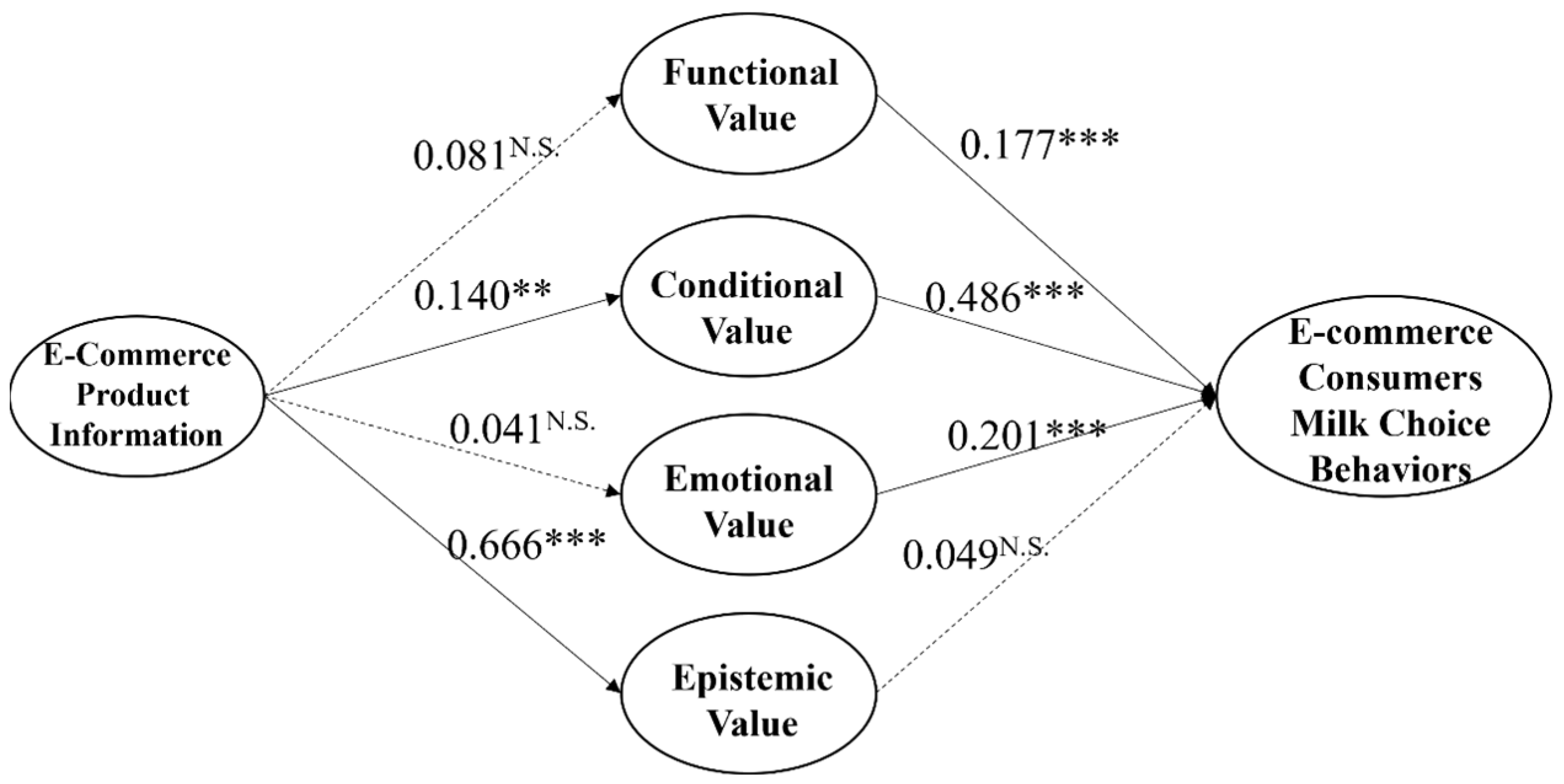

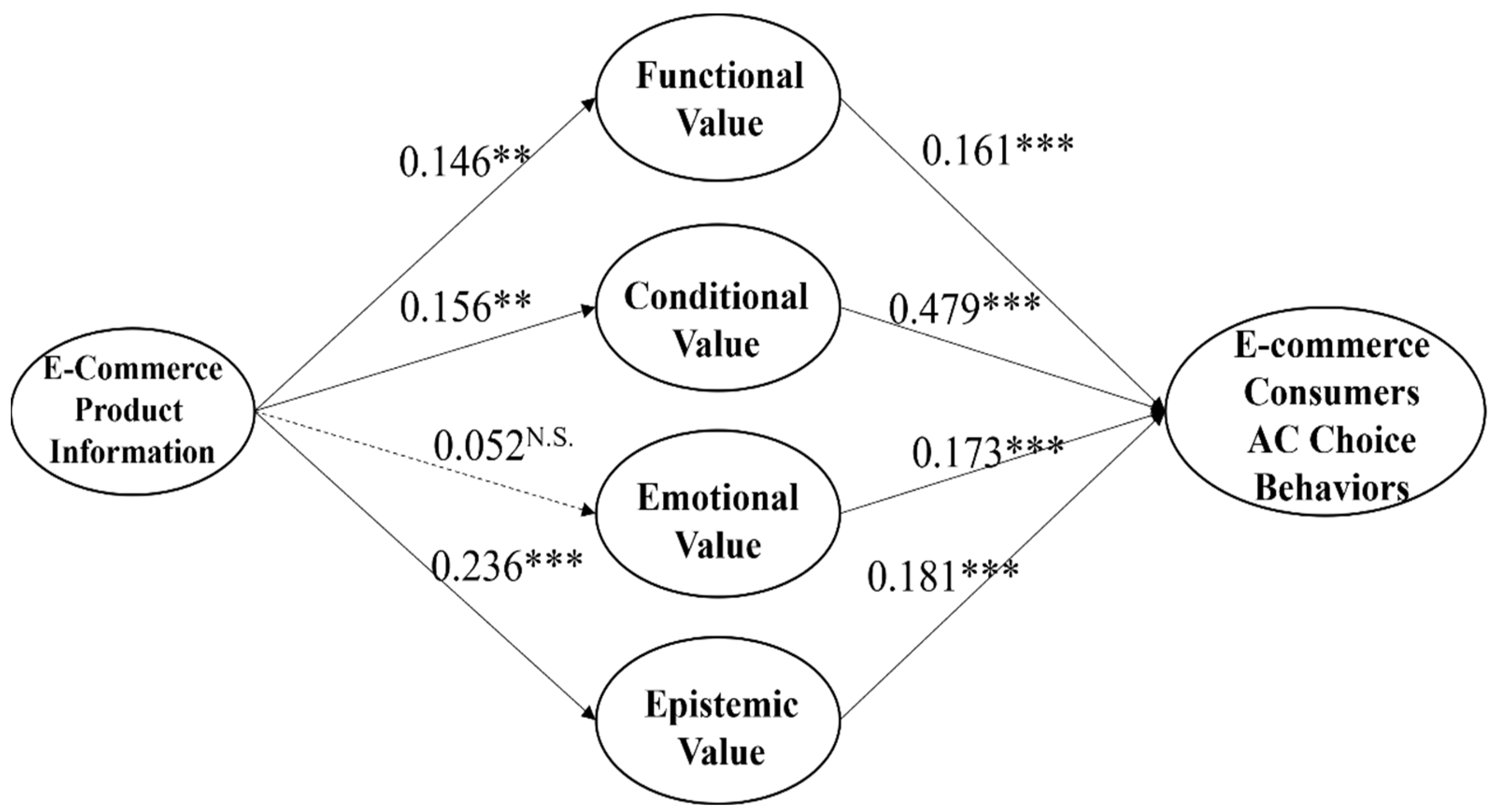

4.1. Structural Equation Results

4.2. Differentiated Analysis of the Consumption Value of Different Product Types

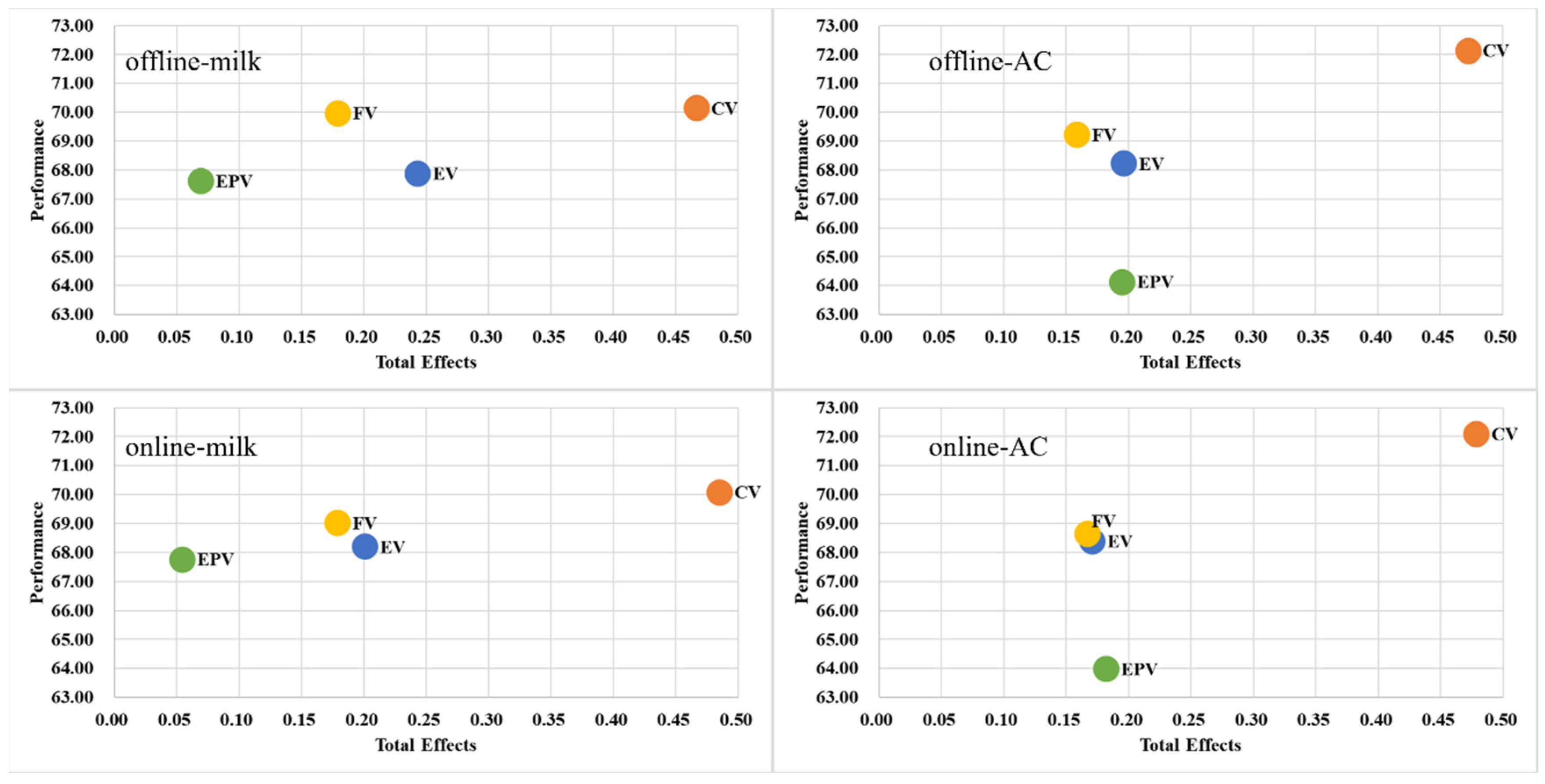

4.2.1. IPMA Analysis

4.2.2. MGA Analysis

4.3. Mediating Effect of Consumption Values

4.4. Heterogeneity Analysis Based on Consumer Characteristics

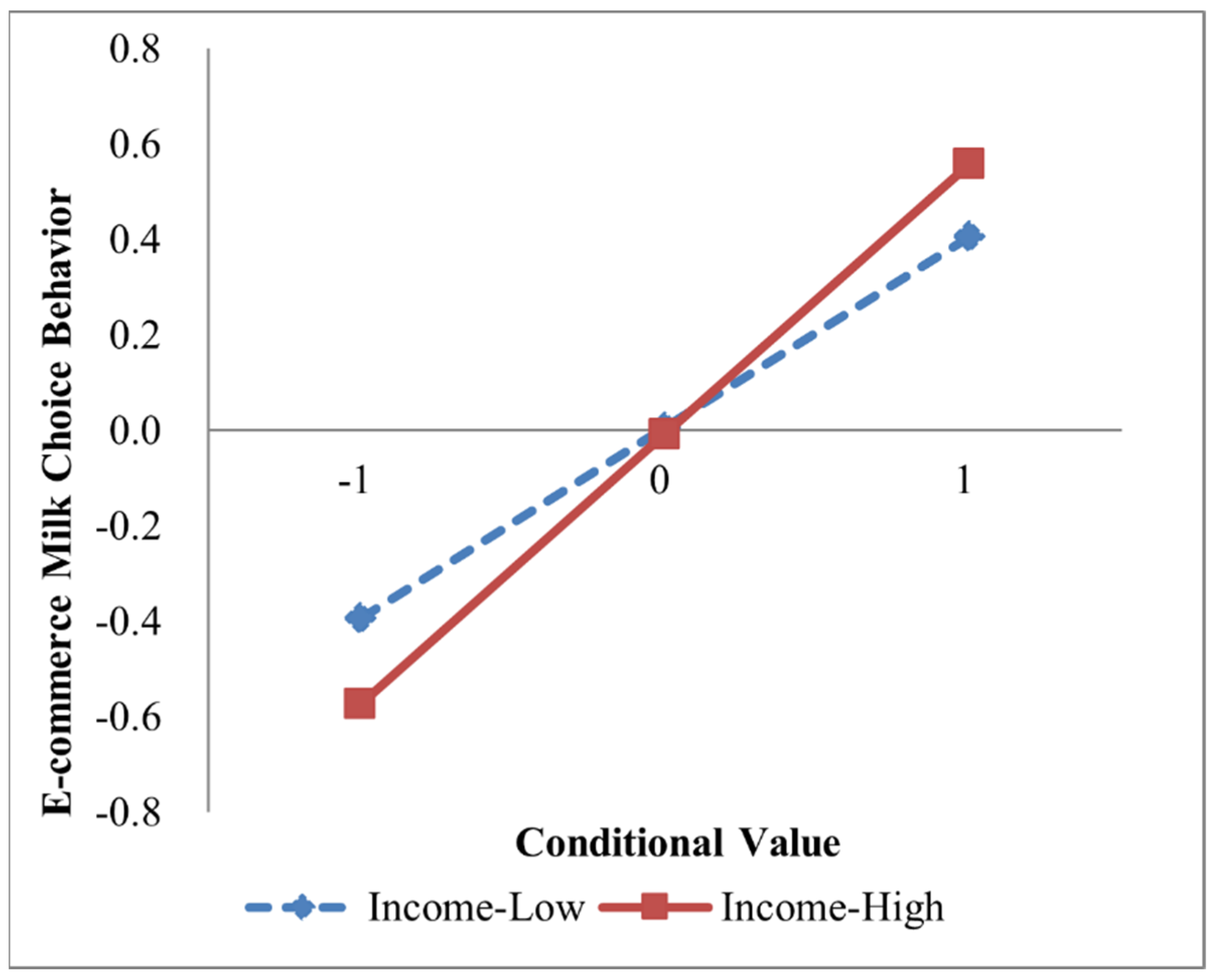

4.4.1. Income Analysis

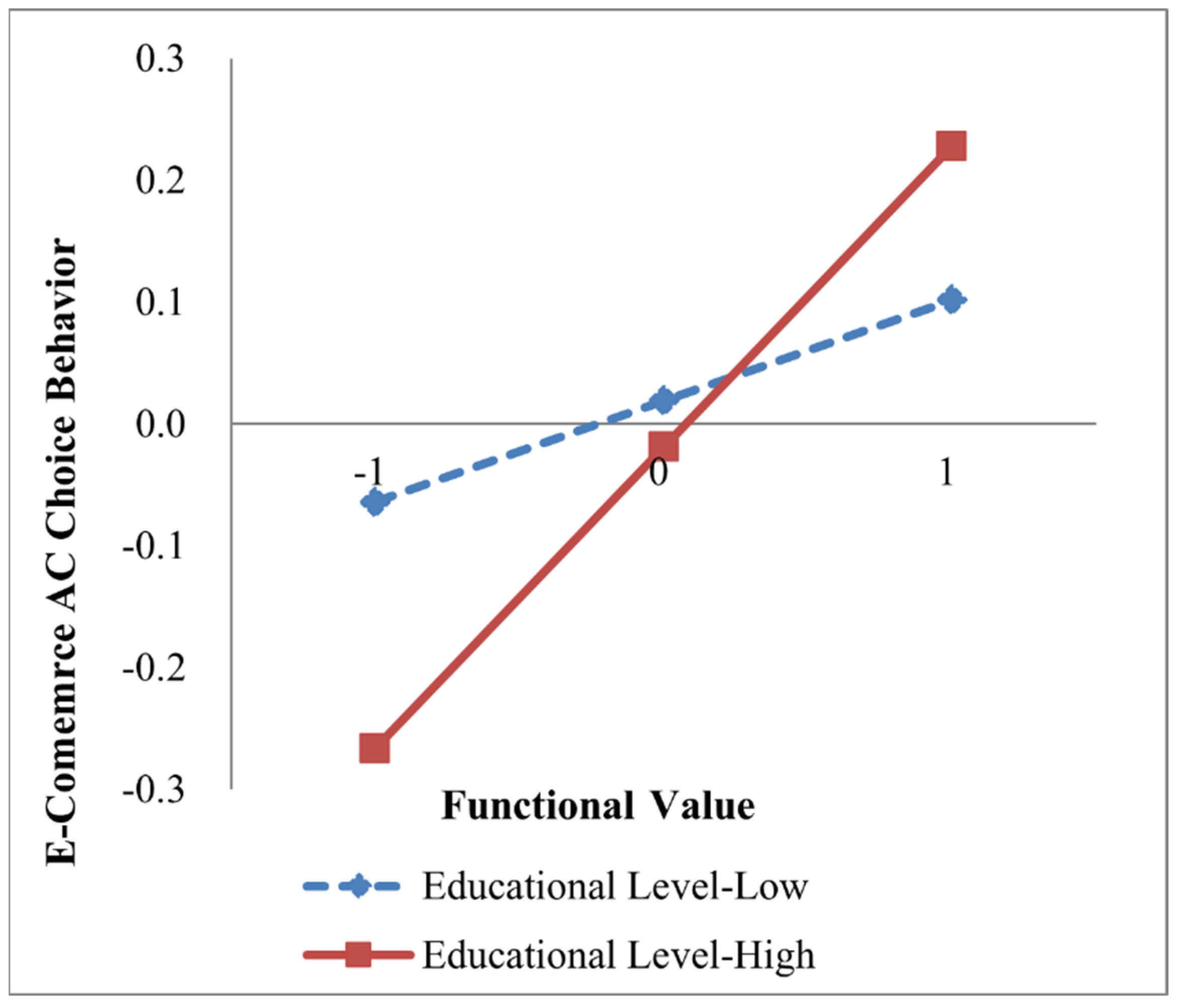

4.4.2. Education Analysis

5. Discussion

5.1. Results Analysis

5.2. Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yuan, R.; Jin, S.; Lin, W. Could Trust Narrow the Intention-Behavior Gap in Eco-Friendly Food Consumption? Evidence from China. Agribusiness 2025, 41, 260–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, B.M. Bridging the Intention-Behavior-Gap through Digitalized Information (?)—Two Laboratory Experiments in the Textile Industry. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2025, 84, 104179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.; Nayga, R.M. Green Identity Labeling, Environmental Information, and pro-Environmental Food Choices. Food Policy 2022, 106, 102187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Peng, M.; Li, Y.; Ren, M.; Ma, T.; Zhao, W.; Xu, J. How E-Commerce Product Environmental Information Influences Green Consumption: Intention–Behavior Gap Perspective. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, A.; Roy, M. Leveraging Factors for Sustained Green Consumption Behavior Based on Consumption Value Perceptions: Testing the Structural Model. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 95, 332–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, H.M.; Lourenço, T.F.; Silva, G.M. Green Buying Behavior and the Theory of Consumption Values: A Fuzzy-Set Approach. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 1484–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Wang, S.; Zhao, D.; Li, J. The Intention to Adopt Electric Vehicles: Driven by Functional and Non-Functional Values. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2017, 103, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, D.; Dash, G. Using the Consumption Values to Investigate Consumer Purchase Intentions towards Natural Food Products. Br. Food J. 2022, 125, 551–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, P.-C.; Huang, Y.-H. The Influence Factors on Choice Behavior Regarding Green Products Based on the Theory of Consumption Values. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 22, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, Y. Comparing Influencing Factors of Online and Offline Fresh Food Purchasing: Consumption Values Perspective. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 26, 12995–13015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, H. Leveraging Technology to Communicate Sustainability-Related Product Information: Evidence from the Field. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 362, 132508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Lu, Y.; Wang, B.; Pan, Z. How Do Product Recommendations Affect Impulse Buying? An Empirical Study on WeChat Social Commerce. Inf. Manag. 2019, 56, 236–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavlanova, T.; Benbunan-Fich, R.; Lang, G. The Role of External and Internal Signals in E-Commerce. Decis. Support Syst. 2016, 87, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, L.N.; Tung, L.T. The Second-Stage Moderating Role of Situational Context on the Relationships between eWOM and Online Purchase Behaviour. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2022, 42, 2674–2687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheth, J.N.; Newman, B.I.; Gross, B.L. Why We Buy What We Buy: A Theory of Consumption Values. J. Bus. Res. 1991, 22, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, J.; Soutar, G. Consumer Perceived Value: The Development of a Multiple Item Scale. J. Retail. 2001, 77, 203–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zailani, S.; Iranmanesh, M.; Sean Hyun, S.; Ali, M. Applying the Theory of Consumption Values to Explain Drivers’ Willingness to Pay for Biofuels. Sustainability 2019, 11, 668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, K.; Tapas, P.; Paliwal, M. Evaluating the Effect of Values Influencing the Choice of Organic Foods. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-C.; Dong, C.-M. Exploring Consumers’ Purchase Intention on Energy-Efficient Home Appliances: Integrating the Theory of Planned Behavior, Perceived Value Theory, and Environmental Awareness. Energies 2023, 16, 2669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.N.; Mohsin, M. The Power of Emotional Value: Exploring the Effects of Values on Green Product Consumer Choice Behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 150, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd Suki, N. Consumer Environmental Concern and Green Product Purchase in Malaysia: Structural Effects of Consumption Values. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 132, 204–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, P.; Apaolaza-Ibáñez, V. Consumer Attitude and Purchase Intention toward Green Energy Brands: The Roles of Psychological Benefits and Environmental Concern. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 1254–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Liu, L.; Wang, M.; Jiang, X. Propensity of Green Consumption Behaviors in Representative Cities in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 133, 1328–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Chen, J.; Zhang, R.; Wang, H.H. What Factors Affect Chinese Consumers’ Online Grocery Shopping? Product Attributes, e-Vendor Characteristics and Consumer Perceptions. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2020, 12, 193–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caniels, M.; Lambrechts, W.; Platje, J.; Motylska-Kuzma, A.; Fortunski, B. Impressing My Friends: The Role of Social Value in Green Purchasing Attitude for Youthful Consumers. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 303, 126993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, A. A Consumption Value-Gap Analysis for Sustainable Consumption. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017, 24, 7714–7725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Ding, Z.; Jiang, X.; Sun, J.; Jiang, Y.; Qiang, W. How Does Experience Impact the Adoption Willingness of Battery Electric Vehicles? The Role of Psychological Factors. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 25230–25247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Xiao, C.; Zhou, G. Willingness to Pay a Price Premium for Energy-Saving Appliances: Role of Perceived Value and Energy Efficiency Labeling. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 242, 118555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niedermeier, A.; Emberger-Klein, A.; Menrad, K. Drivers and Barriers for Purchasing Green Fast-Moving Consumer Goods: A Study of Consumer Preferences of Glue Sticks in Germany. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 284, 124804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigurdsson, V.; Larsen, N.M.; Pálsdóttir, R.G.; Folwarczny, M.; Menon, R.G.V.; Fagerstrøm, A. Increasing the Effectiveness of Ecological Food Signaling: Comparing Sustainability Tags with Eco-Labels. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 139, 1099–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, K.H.; Chang, H.H.; Yeh, C.H. The Effects of Consumption Values and Relational Benefits on Smartphone Brand Switching Behavior. Inf. Technol. People 2018, 32, 217–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Y.; Hussin, A.; Busalim, A. Influence of E-WOM Engagement on Consumer Purchase Intention in Social Commerce. J. Serv. Mark. 2018, 32, 493–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.-W.; Chen, Y.-S.; Yeh, Y.-L.; Li, H.-X. Sustainable Consumption Models for Customers: Investigating the Significant Antecedents of Green Purchase Behavior from the Perspective of Information Asymmetry. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2021, 64, 1668–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, D.; Yang, G.; Wang, W.; Wang, Q.; Zhou, D. Appliance Energy Labels and Consumer Heterogeneity: A Latent Class Approach Based on a Discrete Choice Experiment in China. Energy Econ. 2020, 90, 104839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, N.T.K. Understanding the Effects of Eco-Label, Eco-Brand, and Social Media on Green Consumption Intention in Ecotourism Destinations. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 321, 128995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.T.; Limbu, Y.B.; Pham, L.; Zúñiga, M.Á. The Influence of Electronic Word of Mouth on Green Cosmetics Purchase Intention: Evidence from Young Vietnamese Female Consumers. J. Consum. Mark. 2024, 41, 406–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, M.; Rjoub, H.; Yesiltas, M. Environmental Awareness and Guests’ Intention to Visit Green Hotels: The Mediation Role of Consumption Values. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0248815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tandon, A.; Kaur, P.; Bhatt, Y.; Mäntymäki, M.; Dhir, A. Why Do People Purchase from Food Delivery Apps? A Consumer Value Perspective. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 63, 102667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krey, N.; Chuah, S.H.-W.; Ramayah, T.; Rauschnabel, P.A. How Functional and Emotional Ads Drive Smartwatch Adoption: The Moderating Role of Consumer Innovativeness and Extraversion. Internet Res. 2019, 29, 578–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CAITE. Blue Book on the Internet Facilitating the Development of Digital Consumption. Available online: https://www.caitec.org.cn/upfiles/file/2023/3/20230428153742832.pdf (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- National Bureau of Statistics. Statistical Chart of Economic and Social Development Basic Information of the Population of Megacities in the Seventh National Population Census. Available online: http://www.qstheory.cn/dukan/qs/2021-09/16/c_1127863567.htm (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Hair, J.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-Sem: Indeed a Silver Bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbach, N.; Ahlemann, F. Structural Equation Modeling in Information Systems Research Using Partial Least Squares. J. Inf. Technol. Theory Appl. 2010, 11, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Japutra, A.; Kumar Roy, S.; Pham, T.-A.N. Relating Brand Anxiety, Brand Hatred and Obsess: Moderating Role of Age and Brand Affection. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 60, 102465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haridasan, A.C.; Fernando, A.G. Online or In-Store: Unravelling Consumer’s Channel Choice Motives. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2018, 12, 215–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazi, M.A.I.; Masud, A.A.; Yusof, M.F.; Billah, M.A.; Islam, M.A.; Hossain, M.A. The Green Mindset: How Consumers’ Attitudes, Intentions, and Concerns Shape Their Purchase Decisions. Environ. Res. Commun. 2024, 6, 025009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stadelmann, M.; Schubert, R. How Do Different Designs of Energy Labels Influence Purchases of Household Appliances? A Field Study in Switzerland. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 144, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Group | Number | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 25 and 25− | 221 | 18.31% |

| 26~40 | 842 | 69.76% | |

| 41~50 | 107 | 8.86% | |

| 51~60 | 32 | 2.65% | |

| 60+ | 5 | 0.41% | |

| Gender | Male | 497 | 41.18% |

| Female | 710 | 58.82% | |

| Income (yuan/month) | 3000 and 3000− | 145 | 12.01% |

| 3001–5000 | 125 | 10.36% | |

| 5001–8000 | 245 | 20.30% | |

| 8001–10,000 | 254 | 21.04% | |

| 10,001–20,000 | 340 | 28.17% | |

| 20,000+ | 98 | 8.12% | |

| Education | Primary school | 0 | 0 |

| Middle high school | 10 | 0.83% | |

| High school | 64 | 5.30% | |

| College | 901 | 74.65% | |

| Postgraduate | 232 | 19.22% | |

| Product | AC | 598 | 49.54% |

| Milk | 609 | 50.46% | |

| Total | 1207 | 100% | |

| Item | Organic Milk | Energy-Efficient AC | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loadings | Cronbach’s Alpha | CR | AVE | Loadings | Cronbach’s Alpha | CR | AVE | |

| CV1 | 0.83 | 0.71 | 0.84 | 0.63 | 0.82 | 0.71 | 0.84 | 0.63 |

| CV2 | 0.74 | 0.73 | ||||||

| CV3 | 0.82 | 0.82 | ||||||

| EPV1 | 0.82 | 0.73 | 0.84 | 0.64 | 0.86 | 0.84 | 0.90 | 0.75 |

| EPV2 | 0.83 | 0.89 | ||||||

| EPV3 | 0.76 | 0.86 | ||||||

| EV1 | 0.78 | 0.69 | 0.83 | 0.61 | 0.77 | 0.68 | 0.82 | 0.61 |

| EV2 | 0.80 | 0.80 | ||||||

| EV3 | 0.77 | 0.78 | ||||||

| FV1 | 0.70 | 0.78 | 0.85 | 0.53 | 0.67 | 0.78 | 0.85 | 0.52 |

| FV2 | 0.71 | 0.68 | ||||||

| FV3 | 0.70 | 0.66 | ||||||

| FV4 | 0.76 | 0.79 | ||||||

| FV5 | 0.77 | 0.81 | ||||||

| SV1 | 0.91 | 0.84 | 0.90 | 0.75 | 0.88 | 0.80 | 0.88 | 0.71 |

| SV2 | 0.88 | 0.86 | ||||||

| SV3 | 0.81 | 0.79 | ||||||

| CV | EV | EPV | FV | SV | ||

| Organic milk | CV | 0.796 | ||||

| EV | 0.356 | 0.783 | ||||

| EPV | 0.178 | 0.059 | 0.802 | |||

| FV | 0.404 | 0.360 | 0.158 | 0.729 | ||

| SV | 0.090 | 0.080 | 0.304 | 0.182 | 0.869 | |

| CV | EV | EPV | FV | SV | ||

| Energy-efficient AC | CV | 0.793 | ||||

| EV | 0.371 | 0.782 | ||||

| EPV | 0.241 | 0.194 | 0.867 | |||

| FV | 0.415 | 0.395 | 0.241 | 0.724 | ||

| SV | 0.129 | 0.054 | 0.157 | 0.144 | 0.843 |

| Path | Model 1 (Organic Milk) | Model 2 (Energy-Efficient AC) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | Sample Mean | p-Value | β | Sample Mean | p-Value | |

| CV->CC | 0.467 | 0.465 | 0.000 *** | 0.472 | 0.470 | 0.000 *** |

| EV->CC | 0.243 | 0.243 | 0.000 *** | 0.196 | 0.196 | 0.000 *** |

| EPV->CC | 0.069 | 0.071 | 0.050 * | 0.195 | 0.196 | 0.000 *** |

| FV->CC | 0.179 | 0.181 | 0.000 *** | 0.158 | 0.161 | 0.000 *** |

| SV->CC | 0.046 | 0.047 | 0.148 n.s. | −0.028 | −0.022 | 0.323 n.s. |

| Path | Model 1 (Organic Milk) | Model 2 (Energy-Efficient AC) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | Sample Mean | p-Value | β | Sample Mean | p-Value | |

| CV->CC | 0.485 | 0.482 | 0.000 *** | 0.479 | 0.476 | 0.000 *** |

| EV->CC | 0.201 | 0.200 | 0.000 *** | 0.171 | 0.170 | 0.000 *** |

| EPV->CC | 0.055 | 0.058 | 0.175 n.s. | 0.182 | 0.183 | 0.000 *** |

| FV->CC | 0.179 | 0.182 | 0.000 *** | 0.167 | 0.169 | 0.000 *** |

| SV->CC | 0.056 | 0.057 | 0.074 n.s. | −0.018 | −0.012 | 0.509 n.s. |

| Path | Path-Diff (AC vs.–Milk) | p-Value Original 1-Tailed (AC vs. Milk) | p-Value New (AC vs. Milk) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Online | CV->CC | −0.006 | 0.540 | 0.920 n.s. |

| EV->CC | −0.030 | 0.741 | 0.518 n.s. | |

| EPV->CC | 0.127 | 0.017 | 0.035 * | |

| FV->CC | −0.012 | 0.578 | 0.844 n.s. | |

| SV->CC | −0.075 | 0.960 | 0.079 n.s. | |

| Offline | CV->CC | 0.005 | 0.468 | 0.937 n.s |

| EV->CC | −0.047 | 0.856 | 0.287 n.s | |

| EPV->CC | 0.125 | 0.008 | 0.016 * | |

| FV->CC | −0.021 | 0.63 | 0.739 n.s | |

| SV->CC | −0.074 | 0.959 | 0.082 n.s |

| Product | Path | β | Std. | p-Values | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organic milk | INF->CV->CC | 0.068 | 0.023 | 0.003 | ** |

| INF->EPV->CC | 0.033 | 0.032 | 0.302 | n.s. | |

| INF->EV->CC | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.300 | n.s. | |

| INF->FV->CC | 0.014 | 0.009 | 0.120 | n.s. | |

| AC | INF->CV-> CC | 0.075 | 0.024 | 0.002 | ** |

| INF->EPV->CC | 0.043 | 0.014 | 0.003 | ** | |

| INF->EV->CC | 0.009 | 0.008 | 0.229 | n.s. | |

| INF->FV->CC | 0.024 | 0.010 | 0.019 | * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, X.; Peng, M.; Li, Y.; Tian, H.; Ren, M.; Ma, T.; Xu, J. Influences of Product Environmental Information on Consumers’ Purchase Choices: Product Categories Perspective. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6863. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156863

Wang X, Peng M, Li Y, Tian H, Ren M, Ma T, Xu J. Influences of Product Environmental Information on Consumers’ Purchase Choices: Product Categories Perspective. Sustainability. 2025; 17(15):6863. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156863

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Xintian, Meng Peng, Yan Li, Huifang Tian, Muhua Ren, Tao Ma, and Jiayu Xu. 2025. "Influences of Product Environmental Information on Consumers’ Purchase Choices: Product Categories Perspective" Sustainability 17, no. 15: 6863. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156863

APA StyleWang, X., Peng, M., Li, Y., Tian, H., Ren, M., Ma, T., & Xu, J. (2025). Influences of Product Environmental Information on Consumers’ Purchase Choices: Product Categories Perspective. Sustainability, 17(15), 6863. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156863