Employing Structural Equation Modeling to Examine the Determinants of Work Motivation and Performance Management in BUMDES: In Search of Key Driver Factors in Promoting Sustainable Rural Development Strategies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Local Politics

2.2. Village Facilitators

2.3. Recruitment of Administrators

2.4. Training and Education

2.5. Organizational Culture

2.6. Work Motivation

2.7. Management Performance

2.8. Synthesis of Variable Justification and Research Hypothesis

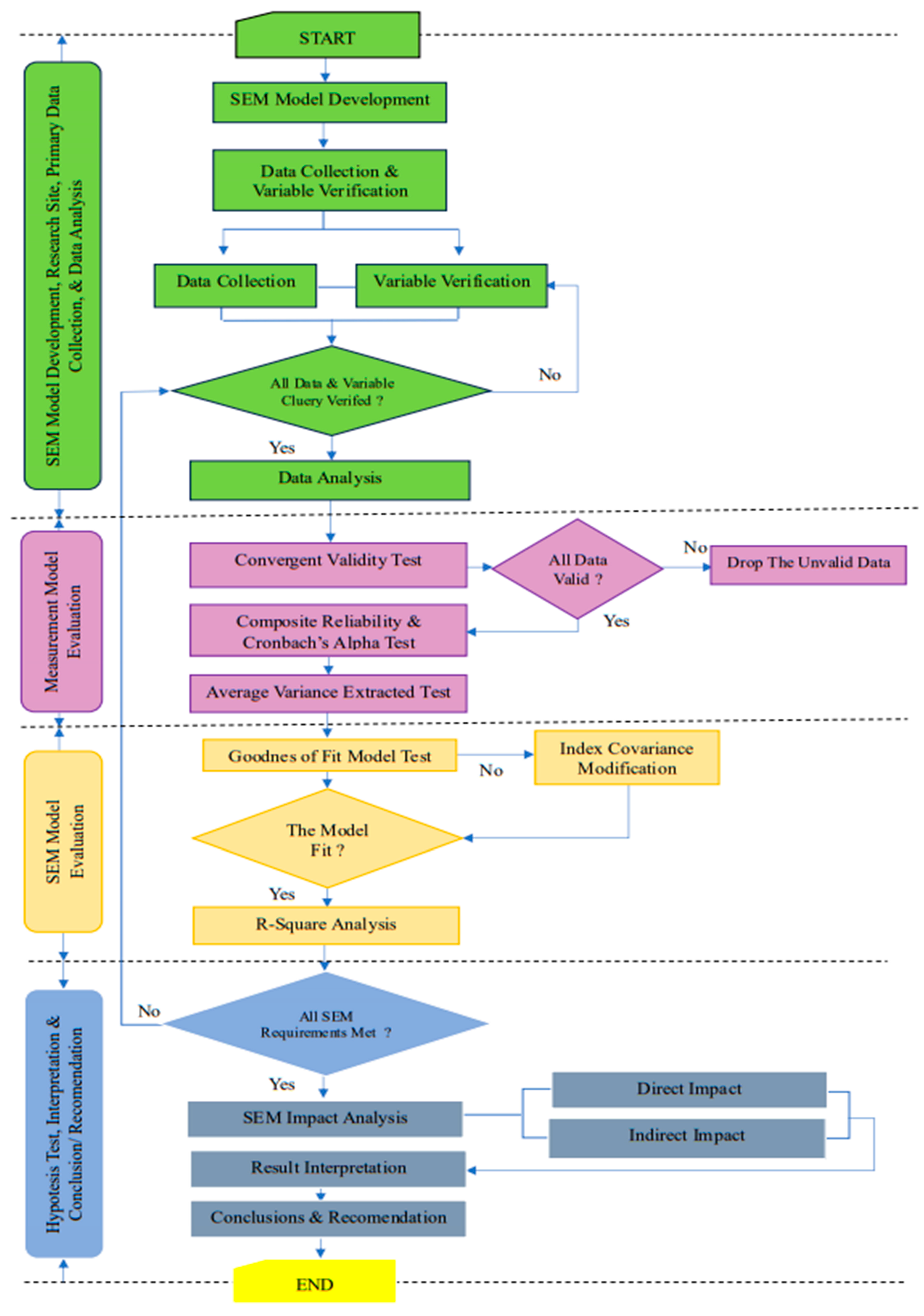

3. Materials and Methods

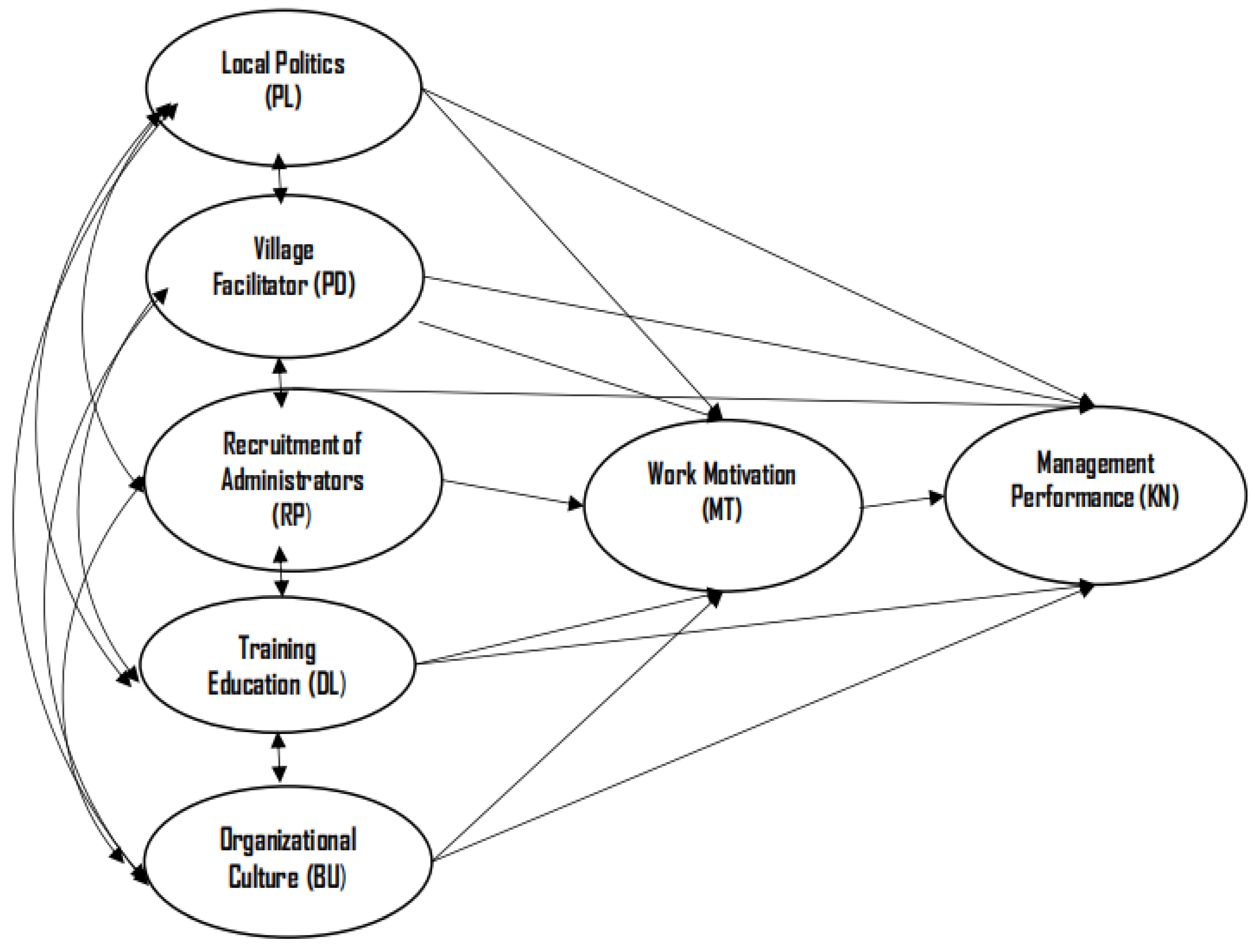

3.1. Construction of Conceptual Framework

3.2. SEM Model Development, Research Site, Primary Data Collection, and Data Analysis

3.2.1. SEM Model Development

3.2.2. Research Site and Primary Data Collection

4. Results

4.1. Data Normality

4.2. Data of Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)/Factor Loading

4.3. Measurement Model Evaluation

4.4. Variance Extracted (VE) and Construct Reliability

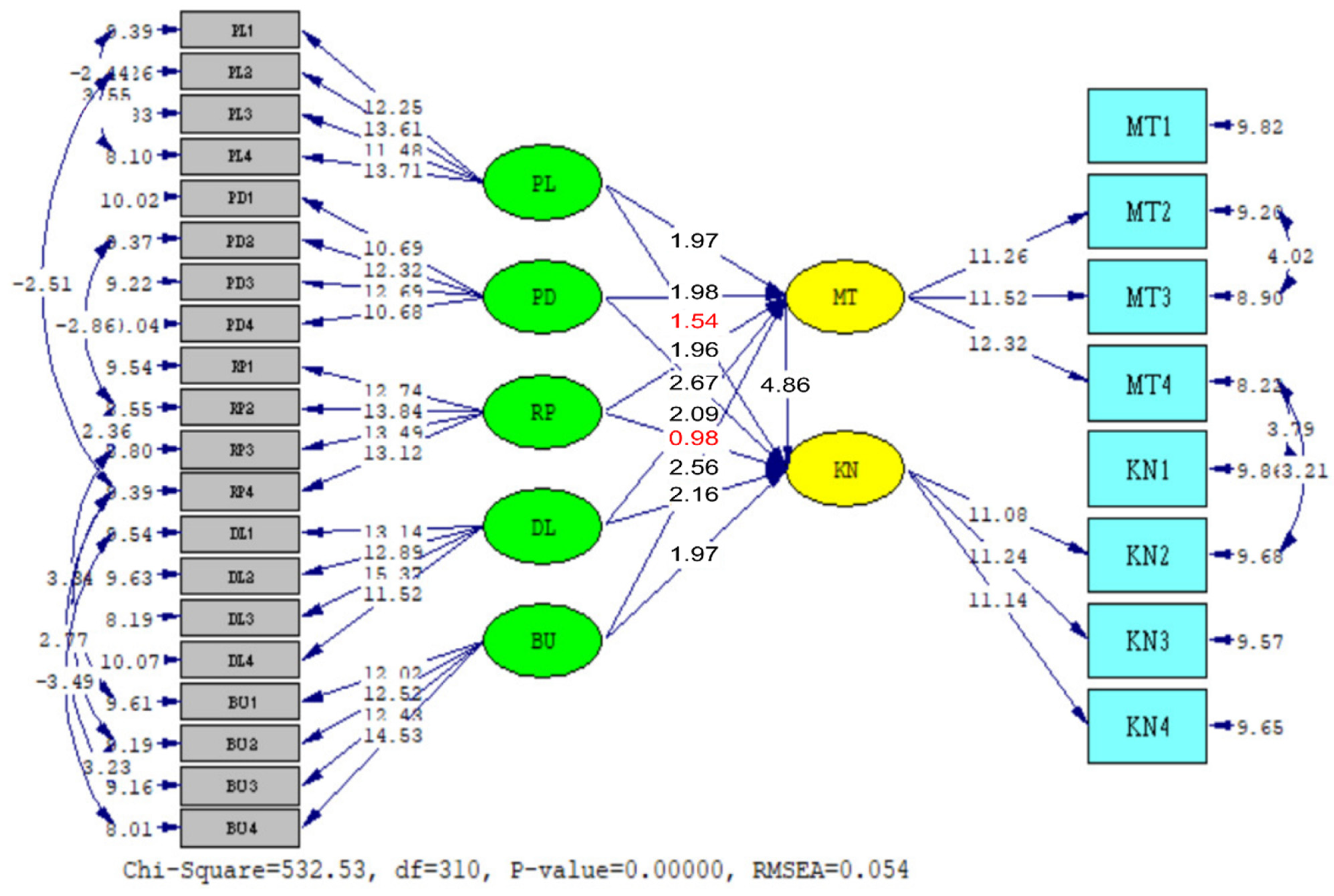

4.5. SEM Model Evaluation

4.5.1. Goodness of Fit

4.5.2. Determinant Coefficient (Structural Model Test)

4.6. Hypothesis Testing and Interpretation

- (1)

- With a t-statistic value of 1.97 and an error value of 0.18, the coefficient of influence of the LV local politics (PL) on the LV work motivation (MT) was 0.23. The strong positive effect of the LV local politics (PL) on the LV of work motivation (MT) was supported by the t-statistic value of 1.97, which is greater than the t-table value of 1.96, so it has a significant effect.

- (2)

- The coefficient of influence of the LV village facilitator (PD) on the LV of work motivation (MT) was 0.15, with an error value of 0.19 and a t-statistic value of 1.98, where this value was greater than the t-table value of 1.96, so it has a significant effect.

- (3)

- The coefficient of influence of the LV of recruitment of administrators (RP) on the LV work motivation (MT) was 0.14, with an error value of 0.21 and a calculated t-value of 1.96. This indicates that the LV of recruitment of administrators (RP) has a significant positive effect on the LV of work motivation (MT), as the calculated t-value of 1.96 was greater than the t-table value of 1.96.

- (4)

- The coefficient value of the effect of the LV training and education (DL) on the LV work motivation (MT) was 0.15, with an error value of 0.16 and a t-statistic value of 2.09, indicating a significant positive relationship between the two variables. This was supported by the t-statistic value of 2.09, greater than the t-table value of 1.96.

- (5)

- The coefficient of influence of the LV organizational culture (BU) on the LV work motivation (MT) was 0.31, with an error value of 0.13 and a t-statistic value of 2.56. It can be concluded that the LV of organizational culture (BU) has a positive effect on the LV of work motivation (MT) because the t-statistic value of 2.56 was greater than the t-table value of 1.96.

- (6)

- The absence of a significant relationship between the LV local politics (PL) and the LV of management performance (KN) was supported by the t-statistic value of 1.54 < the t-table value of 1.96.

- (7)

- The coefficient of influence of the LV of village facilitator (PD) on LV management performance (KN) was 0.49, with an error value of 0.21 and a t-statistic value of 2.67. Because the t-statistic value was 2.67 > the t-table value of 1.96, it was concluded that the LV of village facilitator (PD) has a significant positive effect on the LV of management performance (KN).

- (8)

- The value of the influence coefficient of the LV of recruitment of administrators (RP) on the LV of management performance (KN) was 0.10, the error value was 0.22, and the t-statistical value was 0.98. Because the t-statistical value was 0.98 < the t-table value of 1.96, it was concluded that the LV of recruitment of administrators (RP) was not significant in relation to the LV of management performance (KN).

- (9)

- The value of the coefficient of influence of the LV training and education (DL) variable on the LV management performance (KN) was 0.41, the error value was 0.17, and the t-statistical value was 2.16. Training significantly improves the LV management performance (KN), as the t-statistical value of 2.16 > the t-table value of 1.96.

- (10)

- With a t-statistical value of 1.97 and an error value of 0.17, the influence coefficient of the LV of organizational culture (BU) on the LV of management performance (KN) was 0.32. It may be inferred that the LV of organizational culture (BU) significantly influences the LV of management performance (KN), as the t-statistical value of 1.97 was greater than the t-table value of 1.96. All the test results for indirect relationships between latent variables can be found in Table 15.

- (1)

- With a t-statistical value of 3.14 and an error value of 0.22, the effect coefficient of the LV local politics (PL) was 0.23. The LV of local politics (PL) has a positive effect on the LV of work motivation (MT) through the LV of management performance (KN) (t-statistic = 3.14 > t-table = 1.96).

- (2)

- The LV of village facilitator (PD) had an influence coefficient of 0.27, an error value of 0.15, and a t-statistic value of 2.63 on the LV of management performance (KN) through the LV of work motivation (MT).

- (3)

- The coefficient of influence of the LV recruitment of administrator (RP) was 0.19, with an error value of 0.15 and a t-statistic value of 2.43. This indicates that the LV recruitment of administrators (RP) positively affects the LV of management performance (KN) through the LV work motivation (MT) variable, as evidenced by the t-statistic value of 2.43, which is greater than the t-table value of 1.96.

- (4)

- The coefficient of influence of the LV training and education (DL) was 0.19, with an error value of 0.19 and a t-statistic value of 2.46. This indicates that LV training and education (DL) have a positive and significant impact on LV management performance (KN) through the LV of work motivation (MT). The t-table value of 1.96 is smaller than the t-statistic value of 2.46. The LV organizational culture (BU) had an influence coefficient of 0.19, an error value of 0.14, and a t-statistical value of 2.34.

- (5)

- This shows that the LV organizational culture (BU) significantly affects the LV management performance (KN) through the LV work motivation (MT) (t-table = 1.96 vs. 2.34). We can conclude that LV organizational culture (BU), significantly affects LV work motivation (MT), a latent variable, through management performance (KN), as the t-statistic value was 2.34 > t-table value of 1.96.

5. Discussion

5.1. Direct Effect Between Variables

5.1.1. The Effect of the Latent Variables Local Politics (PL), Village Facilitator (PD), and Recruitment of Administrators (RP) on the Latent Variable Work Motivation (MT)

5.1.2. The Effect of the Latent Variables Training and Education (DL) and Organizational Culture (BU) on the Latent Variable Work Motivation (MT)

5.1.3. The Effect of the Latent Variables Local Politics (PL), Village Facilitator (PD), and Recruitment of Administrators (RP) on the Latent Variable Management Performance (KN)

5.1.4. The Effect of the Latent Variables of Training and Education (DL) and Organizational Culture (BU) on the Latent Variable of Management Performance (KN)

5.2. Indirect Effects Between Latent Variables

5.2.1. The Effect of the Latent Variable Local Politics (PL) on the Latent Variable Management Performance (KN) Through the Latent Variable Work Motivation (MT)

5.2.2. The Influence of the Latent Variables of Village Facilitators (PD) and Recruitment of Administrators (RP) on the Latent Variable of Management Performance (KN) Through the Latent Variable of Work Motivation (MT)

5.2.3. The Effect of the Latent Variables of Training and Education (DL) and Organizational Culture (BU) on the Latent Variable of Management Performance (KN) Through the Latent Variable Work Motivation (MT)

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

6.1. Research Conclusions

6.2. Relevant Recommendations

- (1)

- Given that local politics only indirectly influences management performance through work motivation, local governments need to ensure that political processes do not hinder the management of BUMDES. Instead, local political actors need to be involved in strengthening governance, marketing, and supervision, including the use of digital tools to enhance transparency and oversight, rather than in operational decision-making, which has the potential for bias.

- (2)

- The significant role of village facilitators in motivating work emphasizes the need to strengthen their functions through technical training, regular supervision, and performance-based incentives. Digital skill development and innovative management tools will enhance their capacity to support BUMDES efficiency and work ethics.

- (3)

- Since recruitment of administrators did not have a direct impact on management performance, a merit- and competency-based selection system needs to be established. Implementing digital recruitment systems, open and objective recruitment mechanisms can improve accountability and attract individuals with high work motivation and relevant expertise. Management will be motivated to work and performance will be enhanced because they have the right team members.

- (4)

- Education and training, along with a conducive organizational culture, are key drivers of work motivation and management performance. Therefore, it is essential to develop sustainable training policies that are based on local needs and cultural transformation, supporting innovation, collaboration, and accountability. Using digital learning platforms and innovation-focused content ensures relevance, sustainability, and continuous improvement.

- (5)

- Since work motivation acts as an intermediary in the relationship between structural variables and management performance, policies related to motivation, such as rewards, career development, and the implementation of participatory decision-making processes, need to be applied in the village administration system. Digital participatory tools to promote inclusive, accountable decision-making in village administration should be utilized.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Atkinson, C.L. Global Encyclopedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lestari, T.; Fuady, A.; Yani, F.F.; Putra, I.W.G.A.E.; Pradipta, I.S.; Chaidir, L.; Handayani, D.; Fitriangga, A.; Loprang, M.R.; Pambudi, I.; et al. The development of the national tuberculosis research priority in Indonesia: A comprehensive mixed-method approach. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0281591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Arco, I.; Ramos-Pla, A.; Zsembinszki, G.; de Gracia, A.; Cabeza, L.F. Implementing sdgs to a sustainable rural village development from community empowerment: Linking energy, education, innovation, and research. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridlwan, Z. Payung Hukum Pembentukan BUMDES. Fiat Justitia J. Ilmu Huk. 2015, 7, 355–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ultari, T.; Khoirunurrofik, K. The Role of Village-Owned Enterprises (BUMDes) in Village Development: Empirical Evidence from Villages in Indonesia. J. Perenc. Pembang. Indones. J. Dev. Plan. 2024, 8, 256–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, S.; Hakim, L.; Fatmawati, F.; Tahir, R.; Abdillah, A. Local Capasity, Farmed Seaweed, and Village-Owned Enterprises (BUMDes): A Case Study of Village Governance in Takalar and Pangkep Regencies, Indonesia. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Res. 2023, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmadani; Jayadi, H.; Sarkawi; Kafrawi, R.M.; Setiawan, A. Tantangan Badan Usaha Milik Desa (BUMDES) Dalam Mewujudkan Kemandirian Desa Obstacles Faced by Village-Owned Enterprises (Bumdes). In Attaining Village Autonomy. J. Kompil. Huk. 2024, 9, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aji, J.S.; Retnaningdiah, D.; Hayati, K. The Dynamics of Governance of Village-Owned Enterprise (Bumdes) Amarta in Strengthening the Economy of the Pandowoharjo Village Community During the COVID-19 Pandemic; Atlantis Press: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2022; Volume 1, pp. 563–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aminurosyah, J.; Budiman, B.J.; Alaydrus, A. Demokrasi di Desa (Studi Kasus Pemilihan Kepala Desa Batu Timbau Kabupaten Kutai Timur). J. Gov. Sci. J. Ilmu Pemerintah. 2021, 2, 92–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widodo, T.; Suharyono, S. Pengaruh Perencanaan Serta Pelaksanaan dan Penatausahaan Terhadap Pertanggungjawaban Keuangan BUMDes. Relasi J. Ekon. 2021, 17, 122–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suryadi, A.; Rusli, B.; Alexandri, M.B. Implementasi Kebijakan Badan Usaha Milik Desa (BUMDES) di Kecamatan Pameungpeuk Kabupaten Bandung. Responsive 2021, 4, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pariyanti, E. Peranan Badan Usaha Milik Desa (BUMDES) dalam Meningkatkan Pendapatan Masyarakat Nelayan Desa Sukorahayu Kecamatan Labuhan Maringgai Kabupaten Lampung Timur. Fidusia J. Keuang. Dan Perbank. 2020, 2, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arindhawati, A.T.; Utami, E.R. Dampak Keberadaan Badan Usaha Milik Desa (BUMDes) Terhadap Peningkatan Kesejahteraan Masyarakat (Studi pada Badan Usaha Milik Desa (BUMDes) di Desa Ponggok, Tlogo, Ceper dan Manjungan Kabupaten Klaten). Reviu Akunt. Dan Bisnis Indones. 2020, 4, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triyono, Y.; Kurniasih, D.; Tobirin, T. Menciptakan Kemandirian Desa Melalui Badan Usaha Milik Desa (BUMDes) Untuk Peningkatan Pendapatan Asli Desa (PAD). Co-Value J. Ekon. Kop. Dan Kewirausahaan 2023, 14, 866–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bin Abdullah, H. Implementasi Pengelolaan Badan Usaha Milik Desa (BUMDesa) Jatimakmur Dalam Peningkatan Pendapatan Asli Desa (PADes) Di Desa Jatirejoyoso. J. Gov. Innov. 2021, 3, 204–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firdaus, S. Fenomena Elite Capture dalam Pengelolaan Badan Usaha Milik Desa (Bumdes). Polit. J. Ilmu Polit. 2018, 9, 20–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fyniel, A.; Hapsari, A.N.S. Peran Pendamping Desa dalam Pengelolaan Keuangan Desa. J. Ilm. Akunt. Dan Keuang. 2021, 10, 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fajar, N.; Haning, M.T.; Yunus, M. Pengembangan Kapasitas (Capacity Building) Sumber Daya Manusia Desa Wisata Di Desa Pao Kecamatan Tombolo Pao Kabupaten Gowa. Kolaborasi J. Adm. Publik 2024, 9, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anshori, M.N.; Yusuf, R.; Hasan, R.N. Pengaruh Pelatihan terhadap Kreativitas Masyarakat pada Badan Usaha Milik Desa (Bumdes) Putrajawa Kecamatan Selaawi Garut. J. Pendidik. Hum. Linguist. Dan Sos. 2023, 1, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjeli, A.; Setiyana, R.; Jalil, I.; Rusdi Pengaruh Budaya Organisasi dan Motivasi melalui Kepuasan Kerja terhadap Kinerja Karyawan PT. Dunia Barusa Meulaboh. Cendekia Inov. Dan Berbudaya 2024, 1, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muizu, W.O.Z.; Fu′adi, W.; Masyitoh, I.; Febriani; Triski, D.S. Penguatan dan Pengembangan Revitalisasi BUMDes sebagai Organisasi yang Berkelanjutan dalam Rangka Percepatan Ekonomi Desa. Kaibon Abhinaya J. Pengabdi. Masy. 2024, 6, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isensee, C.; Teuteberg, F.; Griese, K.M.; Topi, C. The relationship between organizational culture, sustainability, and digitalization in SMEs: A systematic review. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 275, 122944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aeni, N. Gambaran Kinerja Badan Usaha Milik Desa (Bumdes) Di Kabupaten Pati. J. Litbang Provinsi Jawa Teng. 2020, 18, 131–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muliantari, L.S.A.; Suarmanayasa, I.N.; Sinarwati, N.K. Analisis Pengelolaan Dan Akuntabilitas Laporan Keuangan Badan Usaha Milik Desa Widya Artha Wiguna Desa Penuktukan, Kecamatan Tejakula Buleleng. Bisma J. Manaj. 2023, 9, 114–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irfan, M.; Santoso, B.; Effendi, L. Pengaruh Partisipasi Anggaran terhadap Senjangan Anggaran dengan Asimetri Informasi, Penekanan Anggaran dan Komitmen Organisasional sebagai Variabel Pemoderasi. J. Akunt. dan Investasi 2016, 17, 158–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, L.; Suamba, I.K.; Arisena, G.M.K. Manajemen, Tantangan dan Hambatan Badan Usaha Milik Desa (BUMDES). Hexagro J. 2022, 6, 22–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmawati, E. Analisis Pengelolaan Badan Usaha Milik Desa (Bum Desa) di Kabupaten Bandung Barat. J. Ilm. Ekon. Bisnis 2020, 25, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senjaya, R.; Ansori, M. Peningkatan Ekonomi Lokal dan Pemberdayaan Masyarakat melalui Bumdes. J. Sains Komun. dan Pengemb. Masy. [JSKPM] 2022, 6, 480–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurnianto, S.; Iswanu, B.I. Governance and Performance of Village-Owned Enterprises (Bumdes). J. Ris. Akunt. dan Bisnis Airlangga 2021, 6, 1150–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudiarta, I.K.G.; Arthanaya, I.W.; Suryani, L.P. Pengelolaan Alokasi Dana Desa dalam Pemerintahan Desa. J. Analog. Huk. 2020, 2, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricart-Angulo, J. The Supremacy of the Executive: Elitist Politics in Indonesia’s Decentralized Reality. Soc. Transform. J. Glob. South 2014, 2, 27–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aluko, Y.A.; Okuwa, O.B. Innovative solutions and women empowerment: Implications for sustainable development goals in Nigeria. Afr. J. Sci. Technol. Innov. Dev. 2018, 10, 441–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambrechts, W.; Verhulst, E.; Rymenams, S. Professional development of sustainability competences in higher education: The role of empowerment. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2017, 18, 697–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosari, R.; Cakranegara, P.A.; Pratiwi, R.; Kamal, I.; Sari, C.I. Strategi Manajemen Sumber Daya Manusia dalam Pengelolaan Keuangan BUMDES di Era Digitalisasi. Own. Ris. J. Akunt. 2022, 6, 2921–2930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillen-Royo, M.; Guardiola, J.; Garcia-Quero, F. Sustainable development in times of economic crisis: A needs-based illustration from Granada (Spain). J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 150, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaedvlieg, J.; Roca, I.M.G.; Ros-Tonen, M.A.F. Is Amazon nut certification a solution for increased smallholder empowerment in peruvian amazonia? J. Rural Stud. 2014, 33, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, Y.; Gimmon, E.; Heilbrunn, S.; Song, S. The impact of gender and political embeddedness on firm performance: Evidence from China. Int. J. Emerg. Mark. 2024, 19, 134–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tantawy, A.A.; Amankwah-Amoah, J.; Puthusserry, P. Political ties in emerging markets: A systematic review and research agenda. Int. Mark. Rev. 2023, 40, 1344–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, S.; Afzaly, A.A.; Kumar, S. Enhancing job embeddedness at work through the leadership styles: A systematic review and future research agenda. Int. J. Appl. Syst. Stud. 2025, 12, 89–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aman-Ullah, A.; Aziz, A.; Ibrahim, H. A Review of Motivational Factors and Employee Retention: A Future Direction for Pakistan. Int. J. Bus. Technopreneursh. 2020, 10, 331–342. [Google Scholar]

- Malik, L.R.; Sharma, D.; Ghosh, K.; Sahu, A.K. Impact of organizational politics on employee outcomes: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2023, 35, 714–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, R. Does public service motivation predict performance in public sector organizations? A longitudinal science mapping study. J. Digit. Manag. 2022, 73, 1237–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, N.T.; Hoang, H.T.; Phan, Q.P.T. Green human resource management: A comprehensive review and future research agenda. Int. J. Manpow. 2019, 41, 845–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, M.; Yadav, R.; Srivastava, A. Employee relations: A comprehensive theory based literature review and future research agenda. Manag. Rev. Q. 2024, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seftyono, C.; Arumsari, N.; Arditama, E.; Lutfi, M. Kepemimpinan Desa dan Pengelolaan Sumber Daya Alam Aras Lokal di Tiga Desa Lereng Gunung Ungaran, Jawa Tengah. Otoritas J. Ilmu Pemerintah. 2016, 6, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handayani, E.; Garad, A.; Suyadi, A.; Tubastuvi, N. Increasing the performance of village services with good governance and participation. World Dev. Sustain. 2023, 3, 100089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foucault, M. The Subject and Power. Crit. Inq. 1982, 8, 777–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Gagné, M. Self-Determination Theory and Work Motivation. J. Organ. Behav. 2005, 26, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anhari, S. Regional-Owned Enterprise is Performance Oriented and Has an Impact on Village Development. Akad. J. Mhs. Ekon. Bisnis 2023, 3, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manor, J.; Crook, R.C. Democracy and Decentralisation in South Asia and West Africa: Participation, Accountability and Performance; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998. Available online: https://www.cambridge.org/core/search?q=Democracy+and+Decentralisation+in+South+Asia+and+West+Africa%3A+Participation%2C+Accountability+and+Performance (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Rahma, A.; Suaedi, F.; Setijaningrum, E. The Effect of Competency and Training on Performance Through Organizational Commitments to Village Apparatus. Airlangga Dev. J. 2022, 6, 78–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivaldi, A. Optimalisasi Peran Pendamping Desa dalam Pembangunan dan Pemberdayaan Masyarakat Desa. Ascarya J. Islam. Sci. Cult. Soc. Stud. 2021, 1, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsson-kanyama, A.; Henrik, K.; Moll, H.C.; Padovan, D. Participative backcasting: A tool for involving stakeholders in local sustainability planning. Futures 2008, 40, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisto, R.; Lopolito, A.; van Vliet, M. Land Use Policy Stakeholder participation in planning rural development strategies: Using backcasting to support Local Action Groups in complying with CLLD requirements. Land Use Policy 2018, 70, 442–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisto, R.; Sica, E.; Cappelletti, G.M. Drafting the strategy for sustainability in universities: A backcasting approach. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Hao, J.; Han, Y. Emerging paradigm in redressing the imbalanced “state-village” power relationship: How have rural gentrifiers bypassed institutional exclusion to influence rural planning processes? J. Rural Stud. 2025, 114, 103564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsden, T.; Murdoch, J. Editorial: The Shifting Nature of Rural Governance and Community Participation. J. Rural Stud. 1998, 14, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noe, R.A.; Clarke, A.D.M.; Klein, H.J. Learning in the Twenty-First-Century Workplace. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2014, 1, 245–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popkova, E. The social management of human capital: Basic principles and methodological approaches. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 2021, 41, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larios-francia, R.P.; Ferasso, M. The relationship between innovation and performance in MSMEs: The case of the wearing apparel sector in emerging countries. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2023, 9, 100018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjaningrum, W.D.; Azizah, N.; Suryadi, N. Spurring SMEs′ performance through business intelligence, organizational and network learning, customer value anticipation, and innovation—Empirical evidence of the creative economy sector in East Java, Indonesia. Heliyon 2024, 10, e27998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, R.; Molina-Castillo, F.J.; Svensson, G. Enterprise resource planning and business model innovation: Process, evolution and outcome. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2020, 23, 728–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anggereni, N.W.E.S. Pengaruh Pelatihan terhadap Kinerja Karyawan pada Lembaga Perkreditan Desa (Lpd) Kabupaten Buleleng. J. Pendidik. Ekon. Undiksha 2019, 10, 606–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutrisno, S.; Permana, R.M.; Junaidi, A. Education and Training as a Means of Developing MSME Expertise. J. Contemp. Adm. Manag. 2023, 1, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idris, B.; Saridakis, G.; Johnstone, S. Training and performance in SMEs: Empirical evidence from large-scale data from the UK. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2023, 61, 769–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaithanapat, P.; Punnakitikashem, P.; Oo, N.C.K.K.; Rakthin, S. Relationships among knowledge-oriented leadership, customer knowledge management, innovation quality and firm performance in SMEs. J. Innov. Knowl. 2022, 7, 100162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Su, X.; Wu, S. Need for achievement, education, and entrepreneurial risk-taking behavior. Soc. Behav. Pers. 2012, 40, 1311–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, Y.H.; Hsu, C.C.; Hung, K.P. Core self-evaluation and workplace creativity. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 1405–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hormati, T. Pengaruh budaya organisasi, rotasi pekerjaan terhadap motivasi kerja dan kinerja pegawai. J. EMBA 2016, 4, 298–310. [Google Scholar]

- Agatz, N.; Erera, A.; Savelsbergh, M.; Wang, X. Optimization for dynamic ride-sharing: A review. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2012, 223, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozak, H.A.; Adhiatma, A.; Fachrunnisa, O.; Rahayu, T. Social Media Engagement, Organizational Agility and Digitalization Strategic Plan to Improve SMEs′ Performance. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2021, 70, 3766–3775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanker, R.; Bhanugopan, R.; van der Heijden, B.I.J.M.; Farrell, M. Organizational climate for innovation and organizational performance: The mediating effect of innovative work behavior. J. Vocat. Behav. 2017, 100, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadam, R.; Rao, S.; Abdul, W.K.; Jabeen, S.S. Impact of cultural intelligence on SME performance: The mediating effect of entrepreneurial orientation. J. Organ. Eff. 2019, 6, 161–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inthavong, P.; Rehman, K.U.; Masood, K. Heliyon Impact of organizational learning on sustainable firm performance: Intervening effect of organizational networking and innovation. Heliyon 2023, 9, e16177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumanti, A.A.; Rizana, A.F.; Achmad, F. Exploring the role of organizational creativity and open innovation in enhancing SMEs performance. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2023, 9, 100045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerasoli, C.P.; Nicklin, J.M.; Ford, M.T. Intrinsic motivation and extrinsic incentives jointly predict performance: A 40-year meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 2014, 140, 980–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syah, B.; Marnisah, L.; Zamzam, F. Pengaruh Kompetensi, Kompensasi dan Motivasi terhadap Kinerja Pegawai Kpu Kabupaten Banyuasin. Integritas J. Manaj. Prof. 2021, 2, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The “What” and “Why” of Goal Pursuits: Human Needs and the Self-Determination of Behavior. Psychol. Inq. 2000, 11, 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zet Ena, S.H.D. Peranan Motivasi Intrinsik Dan Motivasi Ekstrinsik Terhadap Minat Personel Bhabinkamtibmas Polres Kupang Kota. J. Among Makarti 2020, 13, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.H.; Shi, G.; Zhong, H.; Liu, M.T.; Lin, Z. Motivating strategic front-line employees for innovative sales in the digital transformation era: The mediating role of salesperson learning. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2023, 193, 122593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Niu, Y.; Mansor, Z.D.; Leong, Y.C.; Yan, Z. Unlocking digital potential: Exploring the drivers of employee dynamic capability on employee digital performance in Chinese SMEs-moderation effect of competitive climate. Heliyon 2024, 10, e25583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bresciani, S.; Huarng, K.H.; Malhotra, A.; Ferraris, A. Digital transformation as a springboard for product, process and business model innovation. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 128, 204–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J.J.; Rêgo, B.S.; Carayannis, E.G.; Jayantilal, S. Digital Transformation and Strategic Management: A Systematic Review of the Literature. J. Knowl. Econ. 2022, 13, 3195–3222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, J.; Melão, N. Digital transformation: A meta-review and guidelines for future research. Heliyon 2023, 9, e12834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opland, L.E.; Pappas, I.O.; Engesmo, J.; Jaccheri, L. Employee-driven digital innovation: A systematic review and a research agenda. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 143, 255–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacavém, A.; Machado, A.d.B.; dos Santos, J.R.; Palma-Moreira, A.; Belchior-Rocha, H.; Au-Yong-Oliveira, M. Leading in the Digital Age: The Role of Leadership in Organizational Digital Transformation. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putra, A.S.; Hendriani, S.; Samsir. Pengaruh Pelatihan dan Kompetensi terhadap Kinerja Karyawan yang Dimediasi oleh Komitmen pada Pengelola Bumdes di Kabupaten Kuansing. J. Ekon. KIAT 2020, 31, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, N.; Anwar, S.; Haider, N. Effect of Leadership Style on Employee Performance. Arab. J. Bus. Manag. Rev. 2015, 5, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pramana, A.; Sudharma, I. Pengaruh Kompensasi, Lingkungan Kerja Fisik dan Disiplin Kerja terhadap Kinerja Karyawan. E-J. Manaj. Univ. Udayana 2013, 2, 1175–1188. Available online: http://download.garuda.kemdikbud.go.id/article.php?article=1368893&val=989&title=PengaruhKompensasiLingkunganKerjaFisikDanDisiplinKerjaTerhadapKinerjaKaryawan (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Swandari, N.K.A.S.; Setiawina, N.D.; Marhaeni, A.A.I.N. Analisis Faktor-Faktor Penentu Kinerja Karyawan BUMDes di Kabupaten Jembrana. J. Ekon. dan Bisnis 2017, 4, 1365–1394. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, T.; Van Looy, A. Business process management and digital innovations: A systematic literature review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAppio, F.P.; Frattini, F.; Petruzzelli, A.M.; Neirotti, P. Digital Transformation and Innovation Management: A Synthesis of Existing Research and an Agenda for Future Studies. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2021, 38, 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, D.; Konrad, A.M. Causality Between High-Performance Work Systems and Organizational Performance. J. Manag. 2017, 43, 973–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasim, H.; Salam, M.; Sulaiman, A.A.; Jamil, M.H.; Iswoyo, H.; Diansari, P.; Arsal, A.; Tenriawaru, A.N.; Akhsan, A.; Muslim, A.I. Employing Binary Logistic Regression in Modeling the Effectiveness of Agricultural Extension in Clove Farming: Facts and Findings from Sidrap Regency, Indonesia. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamil, M.H.; Salam, M.; Tenriawaru, A.N.; Hardiyanti; Siti; Ramadhani; Anggun; Bidangan, A.M. The effectiveness of agricultural extension in rice farming: Employing structural equation modeling in search for the effective ways in educating farmers. J. Agric. Food Res. 2023, 18, 101487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, N.K.; Guo, S. Structural Equation Modeling; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirgantara, U.; Suryadarma, M. Penerapan Structural Equation Modeling (Sem) Dengan Lisrel Terhadap Perbedaan Tarif Penerbangan Pada Penumpang Domestik Di Bandara Halim Perdanakusuma. J. Sist. Inf. Univ. Suryadarma 2014, 9, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, A.A.; Majumdar, K.; Mishra, R.K. Political factors influencing residents’ support for tourism development in Kashmir. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2022, 8, 718–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarlani, T.; Saraswati, S.; Akliyyah, L.S.; Dananjaya, H.A. Indikator Tata Kelola Badan Usaha Milik Desa (BUMDes) di Indonesia dalam Merespon Era Revolusi Industri 4.0. J. Reg. Urban Dev. 2023, 19, 422–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratulangi, R.S.; Soegoto, A.S. Pengaruh Pengalaman Kerja, Kompetensi, Motivasi Terhadap Kinerja Karyawan (Studi Pada Pt. Hasjrat Abadi Tendean Manado). J. Ris. Ekon. Manaj. Bisnis Dan Akunt. 2016, 4, 323. [Google Scholar]

- Darmaileny, D.; Adriani, Z.; Fitriaty, F. Pengaruh Tata Kelola dan Kompetensi terhadap Kinerja Organisasi Dimediasi Perilaku Inovatif pada Badan Usaha Milik Desa (Bum Desa) dalam Wilayah Kabupaten Tanjung Jabung Barat. J. Ekon. Manaj. Sist. Inf. 2022, 3, 599–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidayahati, A.F.; Rachmawati, I.K. Pengaruh kepemimpinan dan motivasi kerja terhadap disiplin kerja pada bumdes maju bersama Singosari—Kabupaten Malang. JPro 2021, 2, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faslah, R.; Savitri, M.T. Pengaruh Motivasi Kerja dan Disipli Kerja terhadap Produktivitas Kerja pada Karyawan PT Kabelindo Murni, Tbk. J. Pendidik. Ekon. Dan Bisnis 2017, 1, 40–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanani, M.Y.R.; Setiani, S. Pengaruh Islamic Leadership, Budaya Organisasi terhadap Kinerja melalui Motivasi pada Pengurus Pondok Pesantren Sabilul Muttaqin Kota Mojokerto. J. Manaj. STIE 2022, 8, 18–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chintary, V.Q.; Lestari, A.W. Peran Pemerintah Desa dalam Mengelola Badan Usaha Milik Desa (Bumdes). JISIP J. Ilmu Sos. Dan Ilmu Polit. 2016, 5, 59. [Google Scholar]

- Puri, W.H. Politik Balas Budi, Buah Simalakama dalam Demokrasi Agraria Di Indonesia. Masal. Huk. 2019, 48, 355–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martauli, E.D.; Baga, L.M.; Fariyanti, A. Faktor-Faktor yang Berpengaruh terhadap Kinerja Usaha Wanita Wirausaha Kerupuk Udang di Provinsi Jambi. Agrar. J. Agribus. Rural Dev. Res. 2016, 2, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dianto, I. Problematika Pendamping Desa Profesional dalam Pemberdayaan Masyarakat Desa di Kota Padangsidimpuan. Dimas J. Pemikir. Agama untuk Pemberdaya. 2018, 18, 239–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laha, M.S.; Dorohungi, R. Peran Pendamping Desa dalam Pemberdayaan Masyarakat di Distrik Numfor Barat Kabupaten Biak Numfor. J. Gov. Polit. 2021, 1, 27–36. [Google Scholar]

- Wahyudi, H.; Al-Ra’zie, Z.H. Birokrasi sebagai Instrumen Politik Petahana; Kasus Pilkada di Lebong dan Banten. J. Adhikari 2022, 2, 292–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harnawansyah, M.F. Dinamika Politik Daerah dalam Pelaksanaan Sistem Pemilu Umum Legislatif Daerah. Syntax Lit. J. Ilm. Indones. 2019, 4, 50–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widyawati, N.P.A.; Sujana, E.; Yuniarta, G.A. Pengaruh Kompetensi Sumber Daya Manusia, Whistleblowing System, dan Sistem Pengendalian Internal Terhadap Pencegahan Fraud Dalam Pengelolaan Dana BUMDES (Studi Empiris pada Badan Usaha Milik Desa di Kabupaten Buleleng). J. Ilm. Mhs. Akunt. 2019, 10, 368–379. [Google Scholar]

- Septiansyah, B.; Kushartono, T. Peran Badan Usaha Milik Desa (Bumdes) dalam Peningkatan Ekonomi Masyarakat pada Masa Pandemi COVID-19 Di Desa Kertajaya Kecamatan Padalarang Kabupaten Bandung Barat. J. Acad. Praja 2022, 5, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muis, M.R.; Jufrizen, J.; Fahmi, M. Pengaruh Budaya Organisasi dan Komitmen Organisasi terhadap Kinerja Karyawan. Jesya (J. Ekon. Ekon. Syariah) 2018, 1, 9–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutoro, S. Pengaruh Budaya Organisasi terhadap Motivasi Kerja Pegawai BPSDM Provinsi Jambi. J. Ilm. Univ. Batanghari Jambi 2020, 20, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alivia Ayu Sagita Pengaruh Budaya Organisasi terhadap Kinerja Karyawan Melalui Motivasi Kerja sebagai Variabel Intervening. J. Ilmu Manaj. 2019, 7, 265–272.

- Shek, D.T.L.; Yu, L. Confirmatory factor analysis using AMOS: A demonstration. Int. J. Disabil. Hum. Dev. 2014, 13, 191–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.; Ahmad, S.A.; Ahmad, A.; Karim, J.; Akoi, C.; Chowdhury, Z. Smoking Behavior among the Secondary School Students in Bangladesh: Results from Structural Equation Modeling. Ewmc J. 2013, 4, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Astrachan, C.B.; Patel, V.K.; Wanzenried, G. A comparative study of CB-SEM and PLS-SEM for theory development in family firm research. J. Fam. Bus. Strateg. 2014, 5, 116–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishiyaku, B.; Kasim, R.; Harir, A.I. Confirmatory factoral validity of public housing satisfaction constructs. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2017, 4, 1359458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, A.L. Interactive LISREL in Practice; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011. Available online: https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-642-18044-6 (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Farooq, R. Role of structural equation modeling in scale development. J. Adv. Manag. Res. 2016, 13, 75–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdillah, E.; Septianawati, E. Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) on mechanisms of non science students’ attitudes toward statistics courses. J. Focus Action Res. Math. 2023, 6, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putra, W.B.T.S. Problems, Common Beliefs and Procedures on the Use of Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling in Business Research. South Asian J. Soc. Stud. Econ. 2022, 14, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suryani, E.; Saufi, A.; Roro, R.; Aulianasoesetio, D. Open Access Implementation of SEM Partial Least Square in Analyzing the UTAUT Model. Am. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Res. 2024, 8, 215–224. [Google Scholar]

- Latumeten, R.; Lesnussa, Y.A.; Rumlawang, F.Y. Penggunaan Structural Equation Modeling (Sem) untuk Menganalisis Faktor yang Mempengaruhi Loyalitas Nasabah (Studi Kasus: PT Bank Negara Indonesia (BNI) KCU Ambon). Sainmatika J. Ilm. Mat. dan Ilmu Pengetah. Alam 2018, 15, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iskandar, A. Teknik Analisis Validitas Konstruk dan Reliabilitas instrument Test dan Non Test Dengan Software LISREL. Stat. Anal. Manag. Data 2014, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Maulidiyah, R.; Salam, M.; Jamil, M.H.; Tenriawaru, A.N.; Muslim, A.I.; Noralla, H.; Ali, B.; Ridwan, M. Determinants of potato farming productivity and success: Factors and findings from the application of structural equation modeling. HELIYON 2025, 11, e43026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simanjuntak, M.; Hamimi, U. Penanganan Komplain dan Komunikasi Word-Of-Mouth (WOM). J. Ilmu Kel. dan Konsum. 2019, 12, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis; Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010; pp. 1–761, Chapter 1. Available online: https://www.drnishikantjha.com/papersCollection/Multivariate%20Data%20Analysis.pdf (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Asriadi, A.A.; Salam, M.; Nadja, R.A.; Fudjaja, L.; Rukmana, D.; Jamil, M.H.; Arsyad, M.; Rahmadanih; Maulidiyah, R. Determinants of Farmer Participation and Development of Shallot Farming in Search of Effective Farm Management Practices: Evidence Grounded in Structural Equation Modeling Results. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granovetter, M. Economic Action and Social Structure: The Problem of Embeddedness. Am. J. Sociol. 1985, 91, 481–510. Available online: https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/pdf/10.1086/228311 (accessed on 3 June 2025). [CrossRef]

- North, C.D. Institutions, Instutional Change and Economic Performance; Cambrige University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Antlöv, H. Village government and rural development in Indonesia: The new democratic framework. Bull. Indones. Econ. Stud. 2003, 39, 193–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, D. One More Time: How do You Motivate Employess? Westerly 2021, 66, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, T.A.; Robbins, S.P. Organizational Behavior; Pearson: New York City, NY, USA, 2012. Available online: https://www.pearson.com/en-us/subject-catalog/p/organizational-behavior/P200000003606 (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Kristanti, D.; Yudiatmaja, W.E. Antecedents of Work Outcomes of Local Government Employees: The Mediating Role of Public Service Motivation. Policy Gov. Rev. 2022, 6, 247–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warokka, A. Fiscal Decentralization and Special Local Autonomy: Evidence from an Emerging Market. J. Southeast Asian Res. 2013, 2013, 554057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Prayoga, F.; Ananda, C.F.; Brawijaya, U. Rethinking of Local Autonomy and Fiscal Decentralization Policy: Can It Improve The Quality of Human Capital? A Case in Eastern Region of Indonesia. J. Indones. Appl. Econ. 2023, 11, 129–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazala, M.; Vijayendra, R. Localizing Development: Does Participation Work? World Bank’s Open Knowledge Repository: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackman, J.R.; Oldham, G.R. Motivation through the design of work: Test of a theory, Organizational Behaviour and Human Performance. Organ. Behav. Hum. Perform. 1976, 16, 250–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susanti, M.H. Peran Pendamping Desa dalam Mendorong Prakarsa dan Partisipasi Masyarakat Menuju Desa Mandiri Di Desa Gonoharjo Kecamatan Limbangan Kabupaten Kendal. Integralistik 2017, 28, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, G.S. Human Capital: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis, with Special Reference to Education; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfiansyah, R. Social capital as a BUMDes instrument in community empowerment in Sumbergondo Village, Batu City. J. Sosiol. Dialekt. 2022, 17, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haryani, S.; Khairin, F.N. Collaboration Towards a Sustainable Village: The Role of Good Corporate Governance in Transforming Village-owned enterprise (BUMDes) of Surya Jaya Abadi Village. Int. J. Res. Rev. 2025, 12, 554–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KHOSYI, Y.A. Analisis Bumdes Berdasarkan Prinsip Good Corporte Governance Perspektif Ekonomi Islam (Studi Pada Bumdes Amanah Jetis). 2022. Available online: https://dspace.uii.ac.id/bitstream/handle/123456789/39122/15423061.pdf (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Widodo, S.; Saptawan, A.; Purnama, D.H.; Alamsyah; Ismail, R.G.; Nurhasan; Priyanto, L. Pendampingan Manajemen Strategis Pada Perangkat Desa dan Pengelola BUMDes Desa Tanjung Dayang. I-Com Indones. Community J. 2023, 3, 1635–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuvaas, B. An exploration of how the employee-organization relationship affects the linkage between perception of developmental human resource practices and employee outcomes. J. Manag. Stud. 2008, 45, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas, E.; Tannenbaum, S.I.; Kraiger, K.; Smith-Jentsch, K.A. The Science of Training and Development in Organizations: What Matters in Practice. Psychol. Sci. Public Interes. Suppl. 2012, 13, 74–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Taneja, M. The effect of training on employee performance. Int. J. Recent Technol. Eng. 2020, 4, 388–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, M. the Effect of Education, Training, and Motivation on the Civil Servant Performance At the City Population and Civil Registration Office, East Seram. J. Entrep. 2023, 2, 78–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mere, K.; Lukitaningtyas, F.; Sungkawati, E. Competence and Motivation: Keys to Success for BUMDes Management. Dinnasti Int. J. Econ. 2024, 5, 3307–3315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, B.; Ehrhart, M.G.; MacEy, W.H. Organizational climate and culture. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2013, 64, 361–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edgar, P.S.; Schein, H. Organizational Culture and Leadership. In The Innovator’s Discussion; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, S.E.; Nahrgang, J.D.; Morgeson, F.P. Integrating Motivational, Social, and Contextual Work Design Features: A Meta-Analytic Summary and Theoretical Extension of the Work Design Literature. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 1332–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turmudhi, A.; Kurdaningsih, D.M. Improving the performance of BUMDes employees through work discipline and organizational culture. Int. J. Health Sci. 2022, 6, 4680–4686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.; Rowan, B. Institutionalized Organizations: Formal Structure as Myth and Ceremony. Am. J. Sociol. 1977, 83, 340–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grindle, S.M. Getting Good Government: Capacity Building in The Public Sector of Developing Countries; Harvard Institute for International Development: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1997. Available online: https://www.worldcat.org/title/36531293 (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Febrianti, S.A.; Hayati, M. Penguatan Kelembagaan Bumdes Wartim Maslahah melalui Pendampingan Tata Kelola Bumdes Desa Waru Timur Kabupaten Pamekasan Jawa Timur. J. Abdi Masy. Indones. 2023, 3, 335–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammed, M.H. Book Review: Making Democracy Work: Civic Tradition in Modern Italy. Pakistan Adm. Rev. 2020, 4, 12–14. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/348649648 (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Khan, R.A.G.; Khan, A.F.; Khan, M.A. Impact of Training and Development on Organizational Performance. Glob. J. Manag. Bus. Res. 2011, 11, 51–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariska, I.; Dasila, R.A.; Sari, N. Pengaruh Teknologi Informasi Akuntansi, Kompetensi, dan Pelatihan terhadap Kualitas Laporan Keuangan BUMDes. Jesya 2023, 6, 1447–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denison, D.; Mishra, A.K. Toward a theory of Organizational Culture and effectiveness. Organ. Sci. 1995, 6, 204–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olakunle, T. The Impact of Organizational Culture on Employee Productivity. J. Manag. Adm. Provis. 2021, 1, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, W.R.; Davis, G.F. Organizations and Organizing Rational, Natural, and Open System Perspectives; Rountledge Taylor and Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, B.S. Factors Affecting Job Satisfaction of BUMDesa Heads in the District of Bogor, West Java, Indonesia. Sustain. Sci. Resour. 2023, 4, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurkhamid, M.N.; Indra, I.A.; Renny, R.S. Penguatan kapabilitas SDM BUMDesa melalui bimbingan teknis dan pendampingan penyusunan laporan keuangan: Strengthening the capabilities of VOE’s human resources through technical guidance and assistance to prepare financial statements. CONSEN Indones. J. Community Serv. Engagem. 2022, 2, 86–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nubu, A.; Ihsan Mattalitti, M. Peran Pemerintah Desa dalam Pemberdayaan Masyarakat Lokal. Parabela J. Ilmu Pemerintah. Polit. Lokal 2022, 1, 77–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukman, N.; Suryanto; Dally, D. Pengaruh Budaya Organisasi Dan Kepuasan Kerja Dalam Meningkatkan Kinerja Pegawai Yayasan Mutiara Titipan Illahi. J. Niara 2023, 16, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Pelaez, A.; Chura-Quispe, G.; Clemente-Almendros, J.A.; Velarde-Molina, J.F. Analysing the influence of digital strategy and innovation on MSMEs’ performance in emerging countries. Contemp. Account. Inf. Manag. 2025, 34, 351–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoni, D.; Febrianty; Wadud, M. A digital village model for supply chain management capabilities development in micro-small-medium enterprise in South Sumatra. Inf. Technol. Dev. 2025, 31, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakhruddin, M.; Yuliani, I.; Azizah, S.N.; Suradi; Koeswinarno. The Influence of Digital Transformation in Speeding Up the Empowerment of the Muslim Women’s Economy to Improve the Performance of Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs) in Ponorogo. In Strategic Islamic Business and Management; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurniasari, E.D.L.F.; Hamid, N.A. Unraveling the impact of financial literacy, financial technology adoption, and access to finance on small medium enterprises business performance and sustainability: A serial mediation model. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2025, 12, 2487837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suresh, R.V.; CM, C.; Alshebami, A.S.; Al Marri, S.H. Transforming lives: The power of entrepreneurial motivation, bricolage, and mobile payments in strengthening livelihoods for micro-entrepreneurs. Discov. Sustain. 2025, 6, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plekhanov, D.; Franke, H.; Netland, T.H. Digital transformation: A review and research agenda. Eur. Manag. J. 2023, 41, 821–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Latent Variables (LV) | Indicator Variables | Number of Respondents | Likert Scale Frequencies | Means | Min. Value | Max. Value | Std. Deviation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||||

| LV of Local Politics (PL) | Local Leader Intervention (PL1) | 250 | 0 | 44 | 81 | 86 | 39 | 3.48 | 2 | 5 | 0.958 |

| Kinship Relationship (PL2) | 250 | 0 | 21 | 117 | 71 | 41 | 3.53 | 2 | 5 | 0.865 | |

| BUMDES Development Priority (PL3) | 250 | 0 | 36 | 67 | 112 | 35 | 3.58 | 2 | 5 | 0.902 | |

| Political Elite Intervention (PL4) | 250 | 0 | 20 | 72 | 128 | 30 | 3.67 | 2 | 5 | 0.789 | |

| LV of Village Facilitator (PD) | Facilitator (PD1) | 250 | 0 | 13 | 63 | 137 | 37 | 3.79 | 2 | 5 | 0.753 |

| Motivator (PD2) | 250 | 0 | 11 | 73 | 125 | 41 | 3.78 | 2 | 5 | 0.767 | |

| Supervisor (PD3) | 250 | 0 | 18 | 66 | 124 | 42 | 3.76 | 2 | 5 | 0.816 | |

| Communicator (PD4) | 250 | 0 | 17 | 57 | 129 | 47 | 3.82 | 2 | 5 | 0.812 | |

| LV of Recruitment of Administrators (RP) | Human Resource Needs (RP1) | 250 | 0 | 70 | 64 | 71 | 45 | 3.36 | 2 | 5 | 1.075 |

| Source of Human Resources (RP2) | 250 | 0 | 71 | 77 | 59 | 43 | 3.30 | 2 | 5 | 1.061 | |

| Open Recruitment (RP3) | 250 | 0 | 67 | 81 | 56 | 46 | 3.32 | 2 | 5 | 1.062 | |

| Transparency (RP4) | 250 | 0 | 39 | 53 | 93 | 65 | 3.74 | 2 | 5 | 1.015 | |

| LV of Training and Education (DL) | Knowledge (DL1) | 250 | 0 | 33 | 65 | 112 | 40 | 3.64 | 2 | 5 | 0.905 |

| Skills (DL2) | 250 | 0 | 35 | 75 | 84 | 56 | 3.64 | 2 | 5 | 0.980 | |

| Attitude (DL3) | 250 | 0 | 27 | 77 | 90 | 56 | 3.70 | 2 | 5 | 0.937 | |

| Cooperative Relationship (DL4) | 250 | 0 | 39 | 56 | 107 | 48 | 3.66 | 2 | 5 | 0.962 | |

| LV of Organizational Culture (BU) | Risk Tolerance (BU1) | 250 | 0 | 23 | 77 | 107 | 43 | 3.68 | 2 | 5 | 0.865 |

| Supervision (BU2) | 250 | 0 | 24 | 87 | 87 | 52 | 3.67 | 2 | 5 | 0.913 | |

| Result-Oriented (BU3) | 250 | 0 | 20 | 83 | 87 | 60 | 3.75 | 2 | 5 | 0.912 | |

| Reward (BU4) | 250 | 0 | 20 | 79 | 92 | 59 | 3.76 | 2 | 5 | 0.904 | |

| LV of Work Motivation (MT) | Willingness to Work (MT1) | 250 | 0 | 21 | 62 | 112 | 55 | 3.80 | 2 | 5 | 0.877 |

| Desire for Achievement (MT2) | 250 | 0 | 12 | 72 | 103 | 63 | 3.87 | 2 | 5 | 0.847 | |

| Perseverance at Work (MT3) | 250 | 0 | 11 | 60 | 125 | 54 | 3.89 | 2 | 5 | 0.789 | |

| Forward-Oriented (MT4) | 250 | 0 | 12 | 56 | 132 | 50 | 3.88 | 2 | 5 | 0.777 | |

| LV of Management Performance (KN) | BUMDES Income (KN1) | 250 | 0 | 12 | 64 | 118 | 56 | 3.87 | 2 | 5 | 0.811 |

| Asset Addition (KN2) | 250 | 0 | 19 | 44 | 127 | 60 | 3.91 | 2 | 5 | 0.846 | |

| Increase in Management Salary (KN3) | 250 | 0 | 15 | 44 | 142 | 49 | 3.90 | 2 | 5 | 0.777 | |

| Improving the Quality of Human Resources of the Management (KN4) | 250 | 0 | 9 | 42 | 140 | 59 | 4.00 | 2 | 5 | 0.742 | |

| No. | Latent Variables | Indicator Variables and Symbols | Term Error | No. | Latent Variables | Indicator Variables and Symbols | Term Error |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Management Performance (KN) | BUMDES Income (KN1) | ε1 | 4 | Village Facilitator (PD) | Facilitator (PD1) | δ5 |

| Asset Addition (KN2) | ε2 | Motivator (PD2) | δ6 | ||||

| Increase in Management Salary (KN3) | ε3 | Supervisor (PD3) | δ7 | ||||

| Improving the Quality of Human Resources of the Management (KN4) | ε4 | Communicator (PD4) | δ8 | ||||

| 2 | Work Motivation (MT) | Willingness to Work (MT1) | ε5 | 5 | Recruitment of Administrators (RP) | Human Resource Needs (RP1) | δ9 |

| Desire for Achievement (MT2) | ε6 | Source of Human Resources (RP2) | δ10 | ||||

| Perseverance at Work (MT3) | ε7 | Open Recruitment (RP3) | δ11 | ||||

| Forward-Oriented (MT4) | ε8 | Transparency (RP4) | δ12 | ||||

| 3 | Local Politics (PL) | Local Leader Intervention (PL1) | δ1 | 6 | Training and education (DL) | Knowledge (DL1) | δ13 |

| Kinship Relationship (PL2) | δ2 | Skills (DL2) | δ14 | ||||

| BUMDES Development Priority (PL3) | δ3 | Attitude (DL3) | δ15 | ||||

| Political Elite Intervention (Pl4) | δ4 | Cooperative Relationship (DL4) | δ16 | ||||

| 7 | Organizational Culture (BU) | Risk Tolerance (BU1) | δ17 | Result-Oriented (BU3) | δ19 | ||

| Supervision (BU2) | δ18 | Reward (BU4) | δ20 | ||||

| No. | Latent Variables | Measurable Variables | Unit of Measurement | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indicator Variables and Symbols | Source | Base Data | Scale Range * | Data Entered ** | ||

| 1 | Management Performance (KN) | The BUMDES Revenue (KN1) | [12,13] | Likert Scale | 5 PLS | “SD = 1, D = 2, N = 3, A = 4, SA = 5” |

| Asset Addition (KN2) | [99] | Likert Scale | 5 PLS | “SD = 1, D = 2, N = 3, A = 4, SA = 5” | ||

| The BUMDES Management Income (KN3) | [99,100] | Likert Scale | 5 PLS | “SD = 1, D = 2, N = 3, A = 4, SA = 5” | ||

| Improvement of Human Resource Quality of the Management (KN4) | [101] | Likert Scale | 5 PLS | “SD = 1, D = 2, N = 3, A = 4, SA = 5” | ||

| 2 | Work Motivation (MT) | Willingness to Work (MT1) | [77] | Likert Scale | 5 PLS | “SD = 1, D = 2, N = 3, A = 4, SA = 5” |

| Desire for Achievement (MT2) | [77] | Likert Scale | 5 PLS | “SD = 1, D = 2, N = 3, A = 4, SA = 5” | ||

| Diligence to Work (MT3) | [102] | Likert Scale | 5 PLS | “SD = 1, D = 2, N = 3, A = 4, SA = 5” | ||

| Forward-Oriented (MT4) | [103,104] | Likert Scale | 5 PLS | “SD = 1, D = 2, N = 3, A = 4, SA = 5” | ||

| 3 | Local Politics (PL) | Local Leader Intervention (PL1) | [105] | Likert Scale | 5 PLS | “SD = 1, D = 2, N = 3, A = 4, SA = 5” |

| Kinship Relationship (PL2) | [106] | Likert Scale | 5 PLS | “SD = 1, D = 2, N = 3, A = 4, SA = 5” | ||

| Prioritization of BUMDES Development (PL3) | [105] | Likert Scale | 5 PLS | “SD = 1, D = 2, N = 3, A = 4, SA = 5” | ||

| Political Elite Intervention (PL4) | [107] | Likert Scale | 5 PLS | “SD = 1, D = 2, N = 3, A = 4, SA = 5” | ||

| 4 | Village Facilitator (PD) | Facilitator (PD1) | [17,99] | Likert Scale | 5 PLS | “SD = 1, D = 2, N = 3, A = 4, SA = 5” |

| Motivator (PD2) | [99,108] | Likert Scale | 5 PLS | “SD = 1, D = 2, N = 3, A = 4, SA = 5” | ||

| Supervisor (PD3) | [52,99] | Likert Scale | 5 PLS | “SD = 1, D = 2, N = 3, A = 4, SA = 5” | ||

| Communicator (PD4) | [99,109] | Likert Scale | 5 PLS | “SD = 1, D = 2, N = 3, A = 4, SA = 5” | ||

| 5 | Recruitment of Administrators (RP) | Human Resource Needs (RP1) | [110,111] | Likert Scale | 5 PLS | “SD = 1, D = 2, N = 3, A = 4, SA = 5” |

| Source of Human Resource (RP2) | [110,111] | Likert Scale | 5 PLS | “SD = 1, D = 2, N = 3, A = 4, SA = 5” | ||

| Open recruitment (RP3) | [110,111] | Likert Scale | 5 PLS | “SD = 1, D = 2, N = 3, A = 4, SA = 5” | ||

| Transparency (RP4) | [110,111] | Likert Scale | 5 PLS | “SD = 1, D = 2, N = 3, A = 4, SA = 5” | ||

| 6 | Training and Education (DL) | Knowledge (DL1) | [87,112] | Likert Scale | 5 PLS | “SD = 1, D = 2, N = 3, A = 4, SA = 5” |

| Skill (DL2) | [113] | Likert Scale | 5 PLS | “SD = 1, D = 2, N = 3, A = 4, SA = 5” | ||

| Attitude (DL3) | [87,112] | Likert Scale | 5 PLS | “SD = 1, D = 2, N = 3, A = 4, SA = 5” | ||

| Cooperative Relationship (DL4) | [113] | Likert Scale | 5 PLS | “SD = 1, D = 2, N = 3, A = 4, SA = 5” | ||

| 7 | Organizational Culture (BU) | Risk Tolerance (BU1) | [69,114] | Likert Scale | 5 PLS | “SD = 1, D = 2, N = 3, A = 4, SA = 5” |

| Supervision (BU2) | [115,116] | Likert Scale | 5 PLS | “SD = 1, D = 2, N = 3, A = 4, SA = 5” | ||

| Result-Oriented (BU3) | [69,104] | Likert Scale | 5 PLS | “SD = 1, D = 2, N = 3, A = 4, SA = 5” | ||

| Reward (BU4) | [69,104] | Likert Scale | 5 PLS | “SD = 1, D = 2, N = 3, A = 4, SA = 5” | ||

| Goodness of Fit | Cutoff Value | Goodness of Fit | Cutoff Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chi-Square (χ2) | Small | CMIN/DF | ≤2.00 |

| Significance | ≥0.05 | CFI | ≥0.95 |

| RMSEA | ≤0.08 | IFI | ≥0.90 |

| GFI | ≥0.90 | NFI | ≥0.90 |

| AGFI | ≥0.90 | RMSR | ≤0.08 |

| No. | Indicator Variables | Skewness | Kurtosis | Skewness and Kurtosis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Z-Score | p-Value | Z-Score | p-Value | Chi-Square | p-Value | ||

| 1 | Local Leader Intervention (PL1) | 0.098 | 0.922 | −4.220 | 0.000 | 17.818 | 0.142 |

| 2 | Kinship Relationship (PL2) | 0.153 | 0.878 | −1.852 | 0.064 | 3.454 | 0.178 |

| 3 | BUMDES Development Priority (PL3) | −0.302 | 0.763 | −2.586 | 0.010 | 6.778 | 0.034 |

| 4 | Political Elite Intervention (PL4) | −0.672 | 0.502 | −0.690 | 0.490 | 0.927 | 0.629 |

| 5 | Facilitator (PD1) | −0.891 | 0.373 | −0.298 | 0.765 | 0.883 | 0.643 |

| 6 | Motivator (PD2) | −0.703 | 0.482 | −0.963 | 0.336 | 1.421 | 0.491 |

| 7 | Supervisor (PD3) | −0.831 | 0.406 | −1.318 | 0.188 | 2.428 | 0.297 |

| 8 | Communicator (PD4) | −1.028 | 0.304 | −1.241 | 0.215 | 2.598 | 0.273 |

| 9 | Human Resource Needs (RP1) | 0.806 | 0.420 | −8.853 | 0.000 | 79.017 | 0.102 |

| 10 | Source of Human Resources (RP2) | 0.974 | 0.330 | −8.329 | 0.000 | 70.327 | 0.107 |

| 11 | Open Recruitment (RP3) | 0.761 | 0.446 | −8.303 | 0.000 | 69.514 | 0.110 |

| 12 | Transparency (RP4) | −0.940 | 0.347 | −6.226 | 0.000 | 39.652 | 0.132 |

| 13 | Knowledge (DL1) | −0.467 | 0.640 | −2.702 | 0.007 | 7.522 | 0.123 |

| 14 | Skills (DL2) | −0.625 | 0.532 | −5.013 | 0.000 | 25.517 | 0.221 |

| 15 | Attitude (DL3) | −0.794 | 0.427 | −3.951 | 0.000 | 16.245 | 0.314 |

| 16 | Cooperative Relationship (DL4) | −0.489 | 0.625 | −4.049 | 0.000 | 16.635 | 0.305 |

| 17 | Risk Tolerance (BU1) | −0.592 | 0.554 | −2.280 | 0.023 | 5.551 | 0.362 |

| 18 | Supervision (BU2) | −0.608 | 0.543 | −3.349 | 0.001 | 11.587 | 0.103 |

| 19 | Result-Oriented (BU3) | −0.928 | 0.354 | −3.590 | 0.000 | 13.750 | 0.101 |

| 20 | Reward (BU4) | −0.957 | 0.338 | −3.444 | 0.001 | 12.777 | 0.102 |

| 21 | Willingness to Work (MT1) | −1.062 | 0.288 | −2.655 | 0.008 | 8.177 | 0.117 |

| 22 | Desire for Achievement (MT2) | −1.185 | 0.236 | −2.845 | 0.004 | 9.499 | 0.109 |

| 23 | Perseverance at Work (MT3) | −1.136 | 0.256 | −1.458 | 0.145 | 3.417 | 0.181 |

| 24 | Forward-Oriented (MT4) | −1.118 | 0.264 | −0.976 | 0.329 | 2.201 | 0.333 |

| 25 | BUMDES Income (KN1) | −1.130 | 0.259 | −1.912 | 0.056 | 4.932 | 0.085 |

| 26 | Asset Addition (KN2) | −1.355 | 0.176 | −1.931 | 0.053 | 5.565 | 0.062 |

| 27 | Increase in Management Salary (KN3) | −1.186 | 0.236 | −0.473 | 0.636 | 1.629 | 0.443 |

| 28 | Improving the Quality of Human Resources of the Management (KN4) | −1.391 | 0.164 | −0.619 | 0.536 | 2.318 | 0.314 |

| Skewness | Kurtosis | Skewness and Kurtosis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value | Z-Score | p-Value | Value | Z-Score | p-Value | Chi-Square | p-Value |

| 195.721 | 35.385 | 0.000 | 902.03 | 9.137 | 0.000 | 1335.558 | 0.000 |

| No. | Indicators | Local Politics (PL) | Village Facilitator (PD) | Recruitment of Management (RP) | Education Training (DL) | Organizational Culture (BU) | Work Motivation (MT) | Management Performance (KN) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Local Leader Intervention (PL1) | 0.69 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 2 | Kinship Relationship (PL2) | 0.82 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 3 | BUMDES Development Priority (PL3) | 0.75 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 4 | Political Elite Intervention (PL4) | 0.74 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 5 | Facilitator (PD1) | — | 0.64 | — | — | — | — | — |

| 6 | Motivator (PD2) | — | 0.71 | — | — | — | — | — |

| 7 | Supervisor (PD3) | — | 0.74 | — | — | — | — | — |

| 8 | Communicator (PD4) | — | 0.65 | — | — | — | — | — |

| 9 | Human Resource Needs (RP1) | — | — | 0.72 | — | — | — | — |

| 10 | Source of Human Resources (RP2) | — | — | 0.80 | — | — | — | — |

| 11 | Open Recruitment (RP3) | — | — | 0.80 | — | — | — | — |

| 12 | Transparency (RP4) | — | — | 0.73 | — | — | — | — |

| 13 | Knowledge (DL1) | — | — | — | 0.74 | — | — | — |

| 14 | Skills (DL2) | — | — | — | 0.74 | — | — | — |

| 15 | Attitude (DL3) | — | — | — | 0.83 | — | — | — |

| 16 | Cooperative Relationship (DL4) | — | — | — | 0.67 | — | — | — |

| 17 | Risk Tolerance (BU1) | — | — | — | — | 0.70 | — | — |

| 18 | Supervision (BU2) | — | — | — | — | 0.70 | — | — |

| 19 | Result-Oriented (BU3) | — | — | — | — | 0.77 | — | — |

| 20 | Reward (BU4) | — | — | — | — | 0.80 | — | — |

| 21 | Willingness to Work (MT1) | — | — | — | — | — | 0.70 | — |

| 22 | Desire for Achievement (MT2) | — | — | — | — | — | 0.78 | — |

| 23 | Perseverance at Work (MT3) | — | — | — | — | — | 0.81 | — |

| 24 | Forward-Oriented (MT4) | — | — | — | — | — | 0.84 | — |

| 25 | BUMDES Income (KN1) | — | — | — | — | — | — | 0.73 |

| 26 | Asset Addition (KN2) | — | — | — | — | — | — | 0.74 |

| 27 | Increase in Management Salary (KN3) | — | — | — | — | — | — | 0.74 |

| 28 | Improving the Quality of Human Resources of the Management (KN4) | — | — | — | — | — | — | 0.73 |

| Chi-square = 743.23, df = 329, p-value = 0.0000, RMSEA = 0.071 | ||||||||

| Between | And | Decrease in Chi-Square | New Estimate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prioritization of BUMDES Development (PL3) | Local Leader Intervention (PL1) | 13.20 | −0.12 |

| Prioritization of BUMDES Development (PL3) | Kinship Relationship (PL2) | 31.20 | 0.16 |

| Political Elite Intervention (PL4) | Kinship Relationship (PL2) | 16.40 | −0.10 |

| Source of Human Resource (RP2) | Motivator (PD2) | 9.20 | −0.08 |

| Open Recruitment (RP3) | Source of Human Resource (RP2) | 8.20 | 0.11 |

| Transparency (RP4) | Kinship Relationship (PL2) | 8.00 | −0.08 |

| Risk Tolerance (BU1) | Open Recruitment (RP3) | 12.30 | 0.10 |

| Supervision (BU2) | Transparency (RP4) | 8.20 | −0.09 |

| Result-Oriented (BU3) | Transparency (RP4) | 11.40 | 0.10 |

| Result-Oriented (BU3) | Supervision (BU2) | 12.50 | 0.11 |

| Reward (BU4) | Knowledge (DL1) | 9.70 | −0.08 |

| Willingness to Work (MT1) | Communicator (PD4) | 8.00 | −0.08 |

| Willingness to Work (MT1) | Supervision (BU2) | 20.60 | −0.12 |

| Willingness to Work (MT1) | Reward (BU4) | 9.70 | 0.08 |

| Desire for Achievement (MT2) | Knowledge (DL1) | 10.40 | −0.08 |

| Diligence to Work (MT3) | Desire for Achievement (MT2) | 26.60 | 0.11 |

| BUMDES Income (KN1) | Desire for Achievement (MT2) | 10.30 | −0.07 |

| BUMDES Income (KN1) | Forward-Oriented (MT4) | 18.20 | 0.08 |

| Asset Addition (KN2) | Forward-Oriented (MT4) | 13.00 | 0.07 |

| Improvement in Human Resource Quality of the Management (KN4) | Communicator (PD4) | 8.20 | 0.06 |

| Chi-square = 532.33 |

| Latent Variables | Symbols | PL | PD | RP | DL | BU | MT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Local Politics | PL | 1.00 | |||||

| Village Facilitator | PD | 0.83 | 1.00 | ||||

| (0.04) | |||||||

| 21.80 | |||||||

| Recruitment of Administrators | RP | 0.60 | 0.75 | 1.00 | |||

| (0.05) | (0.04) | ||||||

| 11.30 | 17.25 | ||||||

| Training and Education | DL | 0.76 | 0.78 | 0.83 | 1.00 | ||

| (0.04) | (0.04) | (0.03) | |||||

| 18.31 | 18.64 | 25.04 | |||||

| Organizational Culture | BU | 0.72 | 0.73 | 0.79 | 0.73 | 1.00 | |

| (0.05) | (0.05) | (0.04) | (0.04) | ||||

| 16.00 | 15.56 | 21.21 | 16.58 | ||||

| Work Motivation | MT | 0.75 | 0.77 | 0.73 | 0.78 | 0.78 | 1.00 |

| (0.04) | (0.04) | (0.04) | (0.04) | (0.04) | |||

| 18.23 | 18.16 | 17.61 | 20.09 | 19.70 | |||

| Management Performance | KN | 0.75 | 0.85 | 0.76 | 0.83 | 0.79 | 0.92 |

| (0.04) | (0.04) | (0.04) | (0.03) | (0.04) | (0.02) | ||

| 17.51 | 23.68 | 19.23 | 24.01 | 19.87 | 38.23 | ||

| Description: | Correlation Value | Error | t-Count | ||||

| No. | Correlation Relationships | Symbols | Values | Errors | t-Count | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Local Politics and Village Facilitator | PL and PD | 0.83 | −0.04 | 21.80 | Significant |

| 2 | Local Politics and Recruitment of Administrators | PL and RP | 0.60 | −0.05 | 11.30 | Significant |

| 3 | Local Politics and Training and Education | PL and DL | 0.76 | −0.04 | 18.31 | Significant |

| 4 | Local Politics and Organizational Culture | PL and BU | 0.72 | −0.05 | 16.00 | Significant |

| 5 | Local Politics and Work Motivation | PL and MT | 0.75 | −0.04 | 18.23 | Significant |

| 6 | Local Politics and Management Performance | PL and KN | 0.75 | −0.04 | 17.51 | Significant |

| 7 | Village Facilitator and Recruitment of Administrators | PD and RP | 0.75 | −0.04 | 17.25 | Significant |

| 8 | Village Facilitator and Training and Education | PD and DL | 0.78 | −0.04 | 18.64 | Significant |

| 9 | Village Facilitator and Organizational Culture | PD and BU | 0.73 | −0.05 | 15.56 | Significant |

| 10 | Village Facilitator and Work Motivation | PD and MT | 0.77 | −0.04 | 18.16 | Significant |

| 11 | Village Facilitator and Management Performance | PD and KN | 0.85 | −0.04 | 23.68 | Significant |

| 12 | Recruitment of Administrators and Training and Education | RP and DL | 0.83 | −0.03 | 25.04 | Significant |

| 13 | Recruitment of Administrators and Organizational Culture | RP and BU | 0.79 | −0.04 | 21.21 | Significant |

| 14 | Recruitment of Administrators and Work Motivation | RP and MT | 0.73 | −0.04 | 17.61 | Significant |

| 15 | Recruitment of Administrators and Management Performance | RP and KN | 0.76 | −0.04 | 19.23 | Significant |

| 16 | Training and Education and Organizational Culture | DL and BU | 0.73 | −0.04 | 16.58 | Significant |

| 17 | Training and Education, and Work Motivation | DL and MT | 0.78 | −0.04 | 20.09 | Significant |

| 18 | Training and Education, and Management Performance | DL and KN | 0.83 | −0.03 | 24.01 | Significant |

| 19 | Organizational Culture and Work Motivation | BU and MT | 0.78 | −0.04 | 19.70 | Significant |

| 20 | Organizational Culture and Management Performance | BU and KN | 0.79 | −0.04 | 19.87 | Significant |

| 21 | Work Motivation and Management Performance | MT and KN | 0.92 | −0.02 | 38.23 | Significant |

| Latent Variables | Indicators | Symbols | SLF * | Errors | SLF2 | Construct Reliability | Variance Extracted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Local Politics (PL) | Local Leader Intervention | PL1 | 0.66 | 0.48 | 0.4356 | 0.835687 | 0.507621 |

| Kinship Relationship | PL2 | 0.71 | 0.25 | 0.5041 | |||

| BUMDES Development Priority | PL3 | 0.68 | 0.35 | 0.4624 | |||

| Political Elite Intervention | PL4 | 0.58 | 0.28 | 0.3364 | |||

| Village Facilitator (PD) | Facilitator | PD1 | 0.48 | 0.33 | 0.2304 | 0.778897 | 0.469907 |

| Motivator | PD2 | 0.54 | 0.29 | 0.2916 | |||

| Supervisor | PD3 | 0.60 | 0.30 | 0.3600 | |||

| Communicator | PD4 | 0.52 | 0.38 | 0.2704 | |||

| Recruitment of Administrators (RP) | Human Resource Needs | RP1 | 0.78 | 0.55 | 0.6084 | 0.849284 | 0.585679 |

| Source of Human Resources | RP2 | 0.85 | 0.40 | 0.7225 | |||

| Open Recruitment | RP3 | 0.85 | 0.41 | 0.7225 | |||

| Transparency | RP4 | 0.74 | 0.48 | 0.5476 | |||

| Training and Education (DL) | Knowledge | DL1 | 0.67 | 0.37 | 0.4489 | 0.82963 | 0.550254 |

| Skills | DL2 | 0.72 | 0.44 | 0.5184 | |||

| Attitude | DL3 | 0.77 | 0.29 | 0.5929 | |||

| Cooperative Relationship | DL4 | 0.64 | 0.51 | 0.4096 | |||

| Organizational Culture (BU) | Risk Tolerance | BU1 | 0.60 | 0.38 | 0.3600 | 0.841817 | 0.572027 |

| Supervision | BU2 | 0.69 | 0.36 | 0.4761 | |||

| Result-Oriented | BU3 | 0.70 | 0.34 | 0.4900 | |||

| Reward | BU4 | 0.72 | 0.30 | 0.5184 | |||

| Work Motivation (MT) | Willingness to Work | MT1 | 0.61 | 0.40 | 0.3721 | 0.85852 | 0.602912 |

| Desire for Achievement | MT2 | 0.66 | 0.28 | 0.4356 | |||

| Perseverance at Work | MT3 | 0.64 | 0.22 | 0.4096 | |||

| Forward-Oriented | MT4 | 0.65 | 0.18 | 0.4225 | |||

| Management Performance (KN) | BUMDES Income | KN1 | 0.59 | 0.31 | 0.3481 | 0.826431 | 0.544193 |

| Asset Addition | KN2 | 0.63 | 0.32 | 0.3969 | |||

| Increase in Management Salary | KN3 | 0.58 | 0.27 | 0.3364 | |||

| Improving the Quality of Human Resources of the Management | KN4 | 0.54 | 0.25 | 0.2916 |

| Goodness of Fit | Cut Off Value | Estimation | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chi-Square (χ2) | Small | 532.53 | Fit |

| Signifikansi | ≥0.05 | 0.000 | Not fit |

| RMSEA | ≤0.08 | 0.054 | Fit |

| GFI | ≥0.90 | 0.870 | Marginal Fit |

| AGFI | ≥0.90 | 0.830 | Marginal Fit |

| CMIN/DF | ≤2.00 | 1.717 | Fit |

| CFI | ≥0.95 | 0.990 | Fit |

| IFI | ≥0.90 | 0.990 | Fit |

| NFI | ≥0.90 | 0.970 | Fit |

| RMSR | ≤0.08 | 0.036 | Fit |

| R-Square (R2) | R-Square Adjusted | |

|---|---|---|

| Work Motivation (MT) | 0.74 | 0.74 |

| Management Performance (KN) | 0.92 | 0.82 |

| No. | Direct Influences | Coefficients | Error Values | t-Statistic Values | Descriptions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Local Politics (PL) → Work Motivation (MT) | 0.23 | 0.18 | 1.97 | Significant |

| 2 | Village Facilitator (PD) → Work Motivation (MT) | 0.15 | 0.19 | 1.98 | Significant |

| 3 | Recruitment of Administrators (RP) → Work Motivation (MT) | 0.14 | 0.21 | 1.96 | Significant |

| 4 | Training and Education (DL) → Work Motivation (MT) | 0.15 | 0.16 | 2.09 | Significant |

| 5 | Organizational Culture (BU) → Work Motivation (MT) | 0.31 | 0.13 | 2.56 | Significant |

| 6 | Local Politics (PL) → Management Performance (KN) | 0.12 | 0.19 | 1.54 | Insignificant |

| 7 | Village Facilitator (PD) → Management Performance (KN) | 0.49 | 0.21 | 2.67 | Significant |

| 8 | Recruitment of Administrator (RP) → Management Performance (KN) | 0.10 | 0.22 | 0.98 | Insignificant |

| 9 | Training and Education (DL) → Management Performance (KN) | 0.41 | 0.17 | 2.16 | Significant |

| 10 | Organizational Culture (BU) → Management Performance (KN) | 0.32 | 0.17 | 1.97 | Significant |

| No. | Indirect Influences | Coefficients | Error Values | t-Statistic Values | Descriptions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Local Politics (PL) → Work Motivation (MT) → Management Performance (KN) | 0.23 | 0.22 | 3.14 | Significant |

| 2 | Village Facilitator (PD) → Work Motivation (MT) → Management Performance (KN) | 0.27 | 0.15 | 2.63 | Significant |

| 3 | Recruitment of Administrators (RP) → Work Motivation (MT) → Management Performance (KN) | 0.19 | 0.15 | 2.43 | Significant |

| 4 | Training and Education (DL) → Work Motivation (MT) → Management Performance (KN) | 0.19 | 0.19 | 2.46 | Significant |

| 5 | Organizational Culture (BU) → Work Motivation (MT) → Management Performance (KN) | 0.19 | 0.08 | 2.34 | Significant |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ikram, A.A.D.W.; Salam, M.; AT, M.R.; Muhammad, S. Employing Structural Equation Modeling to Examine the Determinants of Work Motivation and Performance Management in BUMDES: In Search of Key Driver Factors in Promoting Sustainable Rural Development Strategies. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6855. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156855

Ikram AADW, Salam M, AT MR, Muhammad S. Employing Structural Equation Modeling to Examine the Determinants of Work Motivation and Performance Management in BUMDES: In Search of Key Driver Factors in Promoting Sustainable Rural Development Strategies. Sustainability. 2025; 17(15):6855. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156855

Chicago/Turabian StyleIkram, Andi Abdul Dzuljalali Wal, Muslim Salam, M. Ramli AT, and Sawedi Muhammad. 2025. "Employing Structural Equation Modeling to Examine the Determinants of Work Motivation and Performance Management in BUMDES: In Search of Key Driver Factors in Promoting Sustainable Rural Development Strategies" Sustainability 17, no. 15: 6855. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156855

APA StyleIkram, A. A. D. W., Salam, M., AT, M. R., & Muhammad, S. (2025). Employing Structural Equation Modeling to Examine the Determinants of Work Motivation and Performance Management in BUMDES: In Search of Key Driver Factors in Promoting Sustainable Rural Development Strategies. Sustainability, 17(15), 6855. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156855