Space to Place, Housing to Home: A Systematic Review of Sense of Place in Housing Studies

Abstract

1. Introduction

- How is sense of place conceptualized in housing research?

- How is the tripartite model applied across different housing contexts?

- How are the cognitive, affective, and conative components of each indicator manifested in different housing contexts?

- What physical, spatial, environmental, social, cultural, economic, and institutional contextual factors influence the development of a sense of place within housing context?

- How does sustainability manifest through the lens of sense of place within housing?

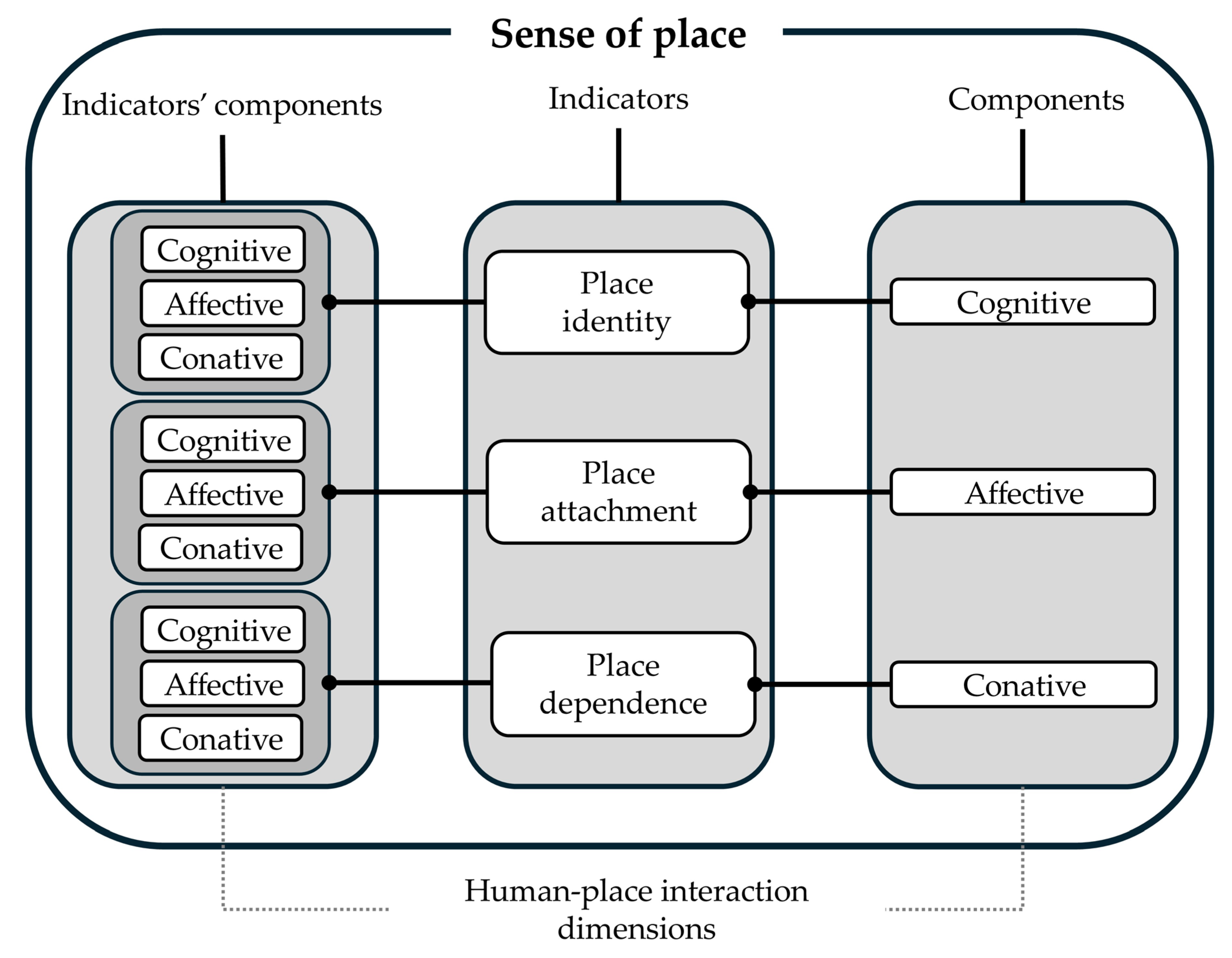

2. Theoretical Framework: Sense of Place as a Core Concept in Human–Place Interaction

2.1. The Tripartite Model of Sense of Place

2.1.1. Place Identity

2.1.2. Place Attachment

2.1.3. Place Dependence

2.2. Expanded Tripartite Model

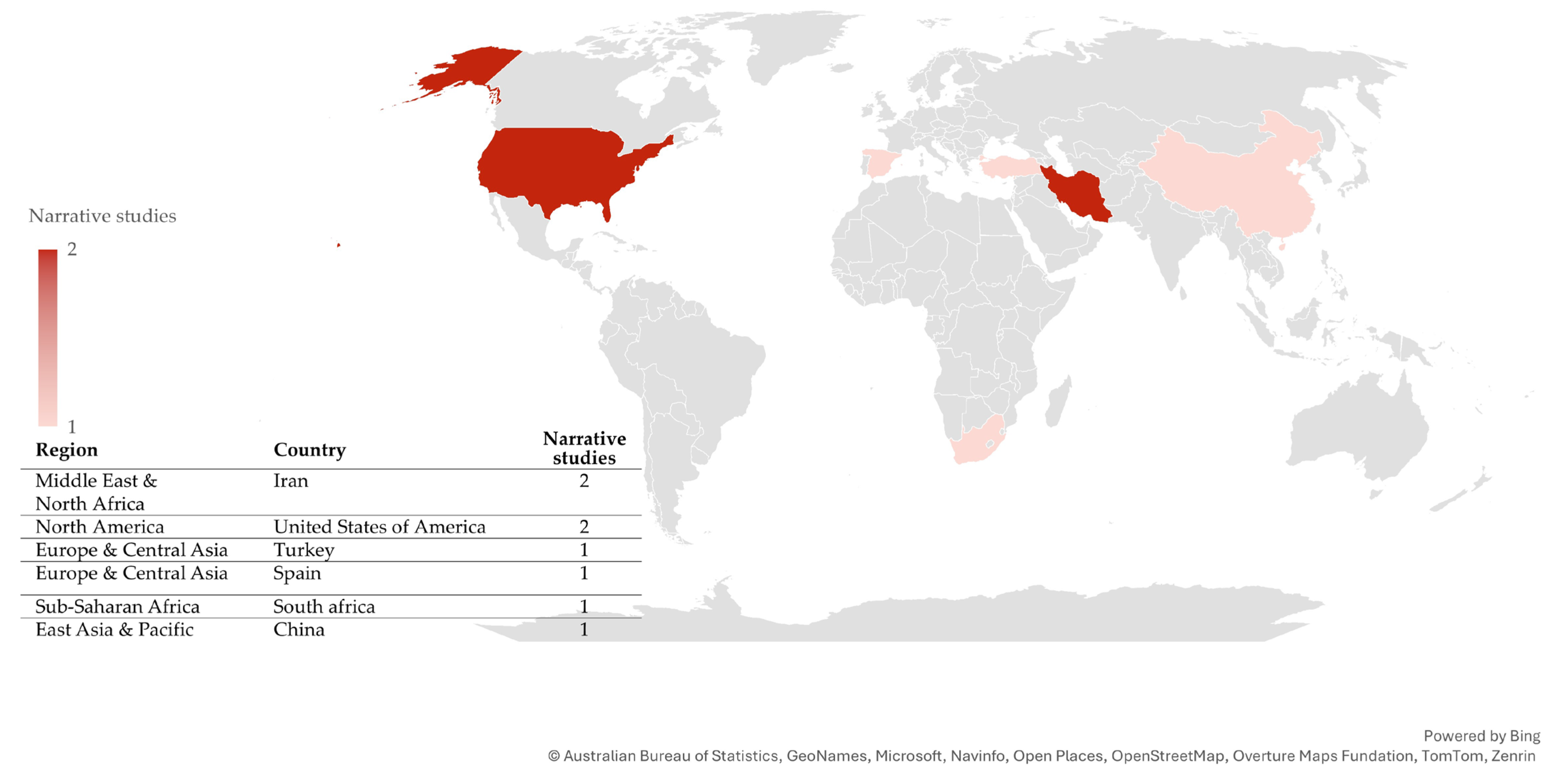

2.3. Conceptual Divergence in the Sense of Place Literature

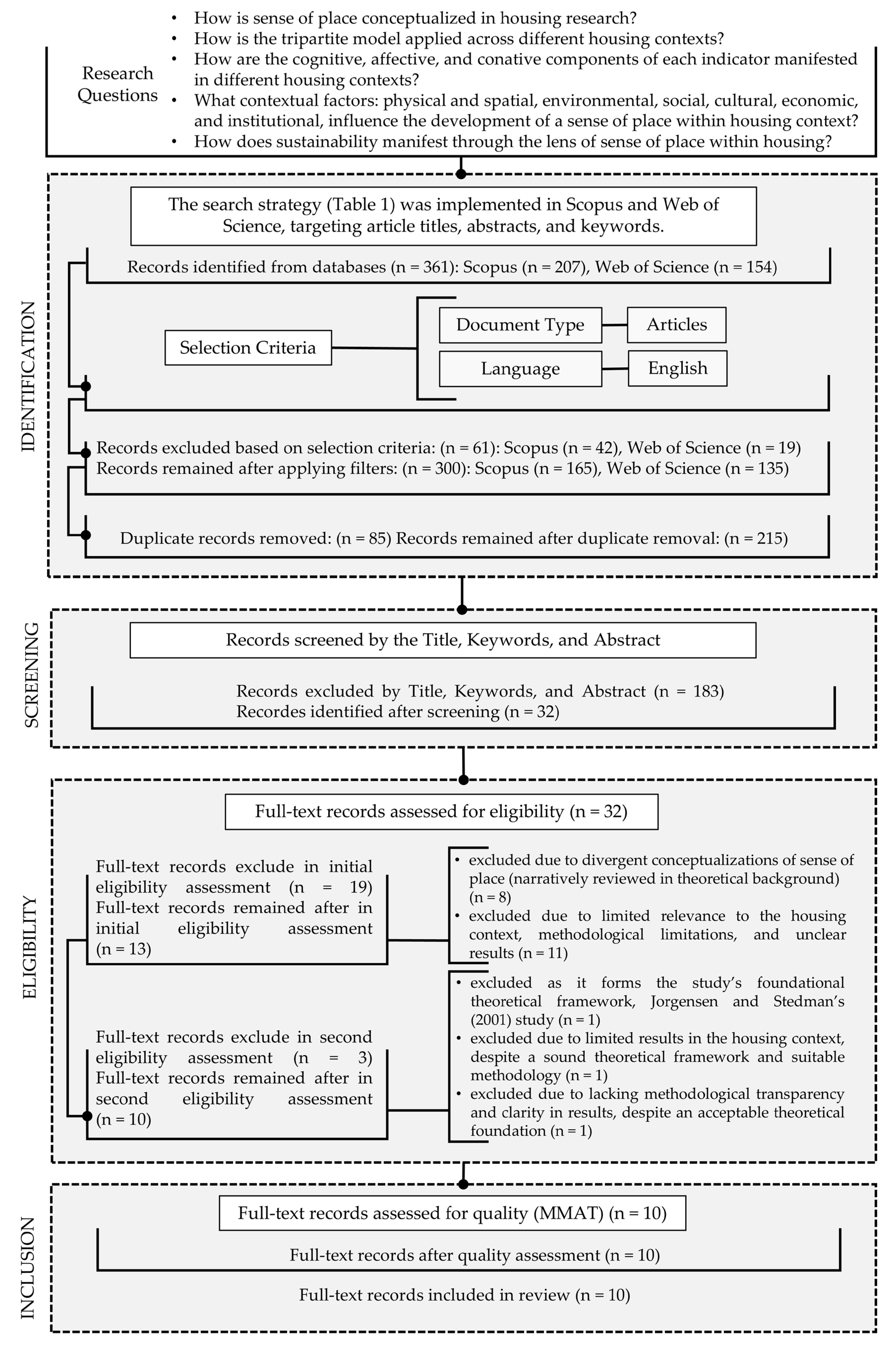

3. Method

3.1. Search Strategy

3.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

3.3. Quality Assessment

3.4. Data Analysis

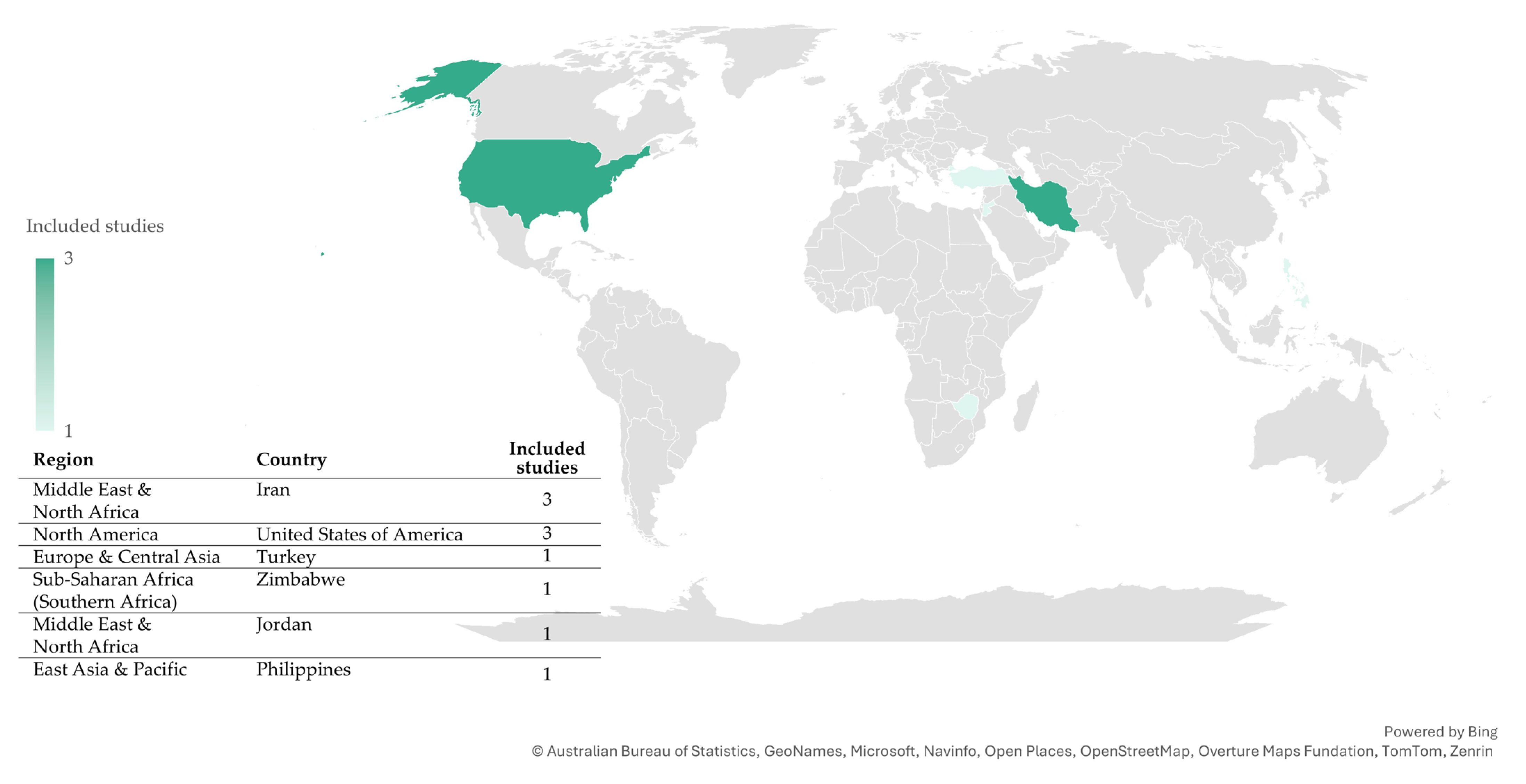

4. Results

4.1. Quantitative Studies

4.2. Qualitative Studies

4.3. Mixed Methods Studies

5. Discussion

5.1. Determinants of Place Identity

5.1.1. Cognitive Component

5.1.2. Affective Component

5.1.3. Conative Component

5.2. Determinants of Place Attachment

5.2.1. Cognitive Component

5.2.2. Affective Component

5.2.3. Conative Component

5.3. Determinants of Place Dependence

5.3.1. Cognitive Component

5.3.2. Affective Component

5.3.3. Conative Component

5.4. Findings and Implications

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| MMAT | Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool |

| SOP | Sense of Place |

| IPA | Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis |

| EUH | Experience Use History |

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

Appendix A

| Boolean Logic | Search Cluster | Keywords 1 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| TITLE-ABS-KEY AND | C1 | Core concept | “Sense of place”, “SOP”, “Sense of home” |

| AND | C2 | Sense of place constructs and indicators | “Genius Loci”, “Spirit of Place”, “Place Identity”, “Place Attachment”, “Place Dependence”, “Affective Attachment”, “Emotional Attachment”, “Place Affect”, “Functional Attachment”, “Sense of Belonging”, “Place Meaning”, “Place Experience”, “Place Perception”, “Place Satisfaction”, “Place Familiarity”, “Topophilia”, “Rootedness”, “Insideness”, “Community Sentiment”, “Loss of Place”, “Non-Place”, “Loss of Nearness”, “Loss of Intimacy”, “Dysphoria” “Diaspora”, “Placeness”, “Placelessness”, “Alienation”, “People-Place Relationship”, “Human–Place Relationship”, “People-Place Interaction”, “Human–Place Interaction” |

| AND | C3 | Setting context | Housing*, House, Home, Residential*, “Domestic Space”, “Domestic Place”, Dwelling* |

| AND | C4 | (Method/Analysis) | Indicator*, Measure*, Factor*, Component*, Variable*, Dimension*, Criteria*, Criterion*, Scale, Framework, Construct, Qualitative, Quantitative |

| Quantitative Descriptive Studies | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Article | Are there clear research questions? | Do the collected data allow to address the research questions? | Is the sampling strategy relevant to address the research question? | Is the sample representative of the target population? | Are the measurements appropriate? | Is the risk of nonresponse bias low? | Is the statistical analysis appropriate to answer the research question? |

| [133] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Can’t tell | Yes | Can’t tell | Yes |

| [134] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Can’t tell | Yes | Can’t tell | Yes |

| [130] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Can’t tell | Yes | Can’t tell | Yes |

| Quantitative non-randomized | |||||||

| Article | Are there clear research questions? | Do the collected data allow to address the research questions? | Are the participants representative of the target population? | Are measurements appropriate regarding both the outcome and intervention (or exposure)? | Are there complete outcome data? | Are the confounders accounted for in the design and analysis? | During the study period, is the intervention administered (or exposure occurred) as intended? |

| [131] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Qualitative | |||||||

| Article | Are there clear research questions? | Do the collected data allow to address the research questions? | Is the qualitative approach appropriate to answer the research question? | Are the qualitative data collection methods adequate to address the research question? | Are the findings adequately derived from the data? | Is the interpretation of results sufficiently substantiated by data? | Is there coherence between qualitative data sources, collection, analysis and interpretation? |

| [138] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| [140] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Mixed methods | |||||||

| Article | Are there clear research questions? | Do the collected data allow to address the research questions? | Is there an adequate rationale for using a mixed methods design to address the research question? | Are the different components of the study effectively integrated to answer the research question? | Are the outputs of the integration of qualitative and quantitative components adequately interpreted? | Are divergences and inconsistencies between quantitative and qualitative results adequately addressed? | Do the different components of the study adhere to the quality criteria of each tradition of the methods involved? |

| [135] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Can’t tell | Yes |

| [132] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Can’t tell | Yes |

| [137] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| [136] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Can’t tell | Yes |

Appendix B

References

- Horlings, L.G. Politics of Connectivity: The Relevance of Place-Based Approaches to Support Sustainable Development and the Governance of Nature and Landscape. In The SAGE Handbook of Nature: Three Volume Set; Marsden, T., Ed.; SAGE Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018; pp. 304–324. [Google Scholar]

- Calvo, M.; De Rosa, A. Design for Social Sustainability. A Reflection on the Role of the Physical Realm in Facilitating Community Co-Design. Des. J. 2017, 20, S1705–S1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norberg-Schulz, C. Genius Loci: Towards a Phenomenology of Architecture; Rizzoli: New York, NY, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal, P. Operationalising ‘Sense of Place’ as a Cognitive Operator for Semantics in Place-Based Ontologies. In Spatial Information Theory; Cohn, A.G., Mark, D.M., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; Volume 3693, pp. 96–114. ISBN 978-3-540-28964-7. [Google Scholar]

- Relph, E. Place and Placelessness; Pion: London, UK, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Tuan, Y.-F. Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Stokols, D.; Shumaker, S.A. People in Places: A Transactional View of Settings. In Cognition, Social Behavior, and the Environment; Harvey, J.H., Ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1981; pp. 441–488. [Google Scholar]

- Tuan, Y.-F. Topophilia: A Study of Environmental Perception, Attitudes, and Values; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Steele, F. The Sense of Place; CBI Publishing Company: Boston, MA, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen, B.; Stedman, R. Sense of Place as an Attitude: Lakeshore Owners Attitudes toward Their Properties. J. Environ. Psychol. 2001, 21, 233–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stedman, R. Sense of Place and Forest Science: Toward a Program of Quantitative Research. For. Sci. 2003, 49, 822–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Ke, Y.; Sankaran, S. The Social Pillar of Sustainable Development: Measurement and Current Status of Social Sustainability of Aged Care Projects in China. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 32, 227–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapin, F.; Knapp, C. Sense of Place: A Process for Identifying and Negotiating Potentially Contested Visions of Sustainability. Environ. Sci. Policy 2015, 53, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masterson, V.A.; Stedman, R.C.; Enqvist, J.; Tengö, M.; Giusti, M.; Wahl, D.; Svedin, U. The Contribution of Sense of Place to Social-Ecological Systems Research: A Review and Research Agenda. Ecol. Soc. 2017, 22, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanzer, B. Measuring Sense of Place: A Scale For Michigan. Adm. Theory Prax. 2004, 26, 362–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foote, K.E.; Azaryahu, M. Sense of Place. In International Encyclopedia of Human Geography; Kitchin, R., Thrift, N., Eds.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2009; pp. 96–100. ISBN 978-0-08-044910-4. [Google Scholar]

- Kearns, A.; Hiscock, R.; Ellaway, A.; MaCintyre, S. Beyond Four Walls. The Psycho-Social Benefits of Home: Evidence from West Central Scotland. Hous. Stud. 2000, 15, 387–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzo, L.C. Beyond House and Haven: Toward a Revisioning of Emotional Relationships with Places. J. Environ. Psychol. 2003, 23, 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, M. Home and State: Reflections on Metaphor and Practice. Griffith Law Rev. 2014, 23, 153–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, S.M.; Altman, I. Place Attachment. In Place Attachment; Altman, I., Low, S.M., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1992; pp. 1–12. ISBN 978-1-4684-8753-4. [Google Scholar]

- Mallett, S. Understanding Home: A Critical Review of the Literature. Sociol. Rev. 2004, 52, 62–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazanti, B. Choosing Residence, Community and Neighbours-Theorizing Families’ Motives for Moving. Geogr. Ann. Ser. B Hum. Geogr. 2007, 89, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wnuk, A.; Góralska, J. ‘Home Is Just a Feeling’: Essentialist and Anti-Essentialist Views on Home among Ukrainian War Refugees. Emot. Space Soc. 2024, 53, 101052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandauko, E.; Asare, A.B.; Arku, G. Exploring Place Attachment Dynamics in Deprived Urban Neighborhoods: An Empirical Study of Nima and Old Fadama Slums in Accra, Ghana. J. Urban Aff. 2023, 47, 1265–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, K.S.; Hagemans, I.W. “Gentrification Without Displacement” and the Consequent Loss of Place: The Effects of Class Transition on Low-Income Residents of Secure Housing in Gentrifying Areas. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2015, 39, 323–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, D.; Zhu, H. Migrant Resettlement in Rural China: Homemaking and Sense of Belonging after Domicide. J. Rural Stud. 2022, 93, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njwambe, A.; Cocks, M.; Vetter, S. Ekhayeni: Rural–Urban Migration, Belonging and Landscapes of Home in South Africa. J. S. Afr. Stud. 2019, 45, 413–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corcoran, M.P. Goda’s Golden Acre for Children’: Pastoralism and Sense of Place in New Suburban Communities. Urban Stud. 2010, 47, 2537–2554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wickramaarachchi, N. Expansion of Commuter Facilities and a Diminishing Sense of Place among Migrants in a Rural Australian Town. Rural Soc. 2020, 29, 44–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghloo, T.; Seyfi, S.; Yarahmadi, M.; Michael Hall, C.; Vo-Thanh, T. Integrating Second Home Owners into Conservative Rural Communities in a Developing Country. Tour. Geogr. 2024, 26, 1197–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billig, M. Is My Home My Castle? Place Attachment, Risk Perception, and Religious Faith. Environ. Behav. 2006, 38, 248–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venables, D.; Pidgeon, N.F.; Parkhill, K.A.; Henwood, K.L.; Simmons, P. Living with Nuclear Power: Sense of Place, Proximity, and Risk Perceptions in Local Host Communities. J. Environ. Psychol. 2012, 32, 371–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S. Anchored in Place, Driven by Risk: How Place Attachment Amplifies the Household Flood Adaptation. Appl. Geogr. 2025, 177, 103547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamani-Fard, A.; Ahmad, M.H.; Ossen, D.R. Sense of Home Place in Participatory Post-Disaster Reconstruction. J. Environ. Assess. Policy Manag. 2013, 15, 1350005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrest, R.; La Grange, A.; Ngai-Ming, Y. Neighbourhood in a High Rise, High Density City: Some Observations on Contemporary Hong Kong. Sociol. Rev. 2002, 50, 215–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baba, C.; Kearns, A.; McIntosh, E.; Tannahill, C.; Lewsey, J. Is Empowerment a Route to Improving Mental Health and Wellbeing in an Urban Regeneration (UR) Context? Urban Stud. 2017, 54, 1619–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloutier-Fisher, D.; Harvey, J. Home beyond the House: Experiences of Place in an Evolving Retirement Community. J. Environ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 246–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zhang, F.; Wu, F. Contrasting Migrants’ Sense of Belonging to the City in Selected Peri-Urban Neighbourhoods in Beijing. Cities 2022, 120, 103499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Wang, Z.; Yang, L. Return or Relocation? Evolving Neighbourhood Attachment of Work-Unit Residents after Gentrification-Induced Displacement in Chengdu, China. Popul. Space Place 2024, 30, e2825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noobanjong, K.; Louhapensang, C. Baan Fai Rim Ping: A Haptic Approach to the Phenomenon of Genius Loci by a Riverside Residence in Thailand. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2023, 22, 355–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Su, L.; Li, Z. How Does the Neighbourhood Environment Influence Migrants’ Subjective Well-Being in Urban China? Popul. Space Place 2024, 30, e2704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Sun, Y.; Yuan, X. Is Mixed-Housing Development Healthier for Residents? The Implications on the Perception of Neighborhood Environment, Sense of Place, and Mental Health in Urban Guangzhou. J. Urban Aff. 2025, 47, 527–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, B.K.; Rahman, M.K.; Crawford, T.; Curtis, S.; Miah, M.G.; Islam, M.R.; Islam, M.S. Explaining Mobility Using the Community Capital Framework and Place Attachment Concepts: A Case Study of Riverbank Erosion in the Lower Meghna Estuary, Bangladesh. Appl. Geogr. 2020, 125, 102199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soaita, A.; Mckee, K. Assembling a “kind of” Home in the UK Private Renting Sector. Geoforum 2019, 103, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearns, R.A.; Smith, C.J. Housing, Homelessness, and Mental Health: Mapping an Agenda for Geographical Inquiry. Prof. Geogr. 1994, 46, 418–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boccagni, P.; Miranda Nieto, A. Home in Question: Uncovering Meanings, Desires and Dilemmas of Non-Home. Eur. J. Cult. Stud. 2022, 25, 515–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, D. Space, Place and Gender; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Altman, I.; Zube, E.H. Introduction. In Public Places and Spaces; Altman, I., Zube, E.H., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1989; pp. 1–5. ISBN 978-1-4684-5601-1. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Tuan, Y.-F. Rootedness versus Sense of Place. Landscape 1980, 24, 3–8. [Google Scholar]

- Buttimer, A. Home, Reach, and the Sense of Place. In The Human Experience of Space and Place; Buttimer, A., Seamon, D., Eds.; St. Martin’s Press: New York, NY, USA, 1980; pp. 166–187. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Jackson, J.B. A Sense of Place, a Sense of Time. Des. Q. 1995, 164, 24–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jive’n, G.; Larkham, P.J. Sense of Place, Authenticity and Character: A Commentary. J. Urban Des. 2003, 8, 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Relph, E. Spirit of Place and Sense of Place in Virtual Realities. Techné Res. Philos. Technol. 2007, 10, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Liu, F. Embracing the Digital Landscape: Enriching the Concept of Sense of Place in the Digital Age. Palgrave Commun. 2024, 11, 724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, J.; Bowman, N.D. Symbolism, Purpose, Identity, Relation, Emotion: Unpacking the SPIREs of Sense of Place across Digital and Physical Spaces. Poetics 2024, 105, 101916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christenson, J.A. Urbanism and Community Sentiment: Extending Wirth’s Model. Soc. Sci. Q. 1979, 60, 387–400. [Google Scholar]

- Gifford, R. Introduction—Special Places. J. Environ. Psychol. 1998, 18, 3–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safran, W. Diasporas in Modern Societies: Myths of Homeland and Return. Diaspora A J. Transnatl. Stud. 2011, 1, 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costonis, J.J. Icons and Aliens: Law, Aesthetics, and Environmental Change; University of Illinois Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Arefi, M. Non-place and Placelessness as Narratives of Loss: Rethinking the Notion of Place. J. Urban Des. 1999, 4, 179–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidegger, M. Building, Dwelling, Thinking. In Poetry, Language, Thought; Hofstadter, A., Ed.; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1971; pp. 141–159. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Bognar, B. A Phenomenological Approach to Architecture and Its Teaching in the Design Studio. In Dwelling, Place and Environment: Towards a Phenomenology of Person and World; Seamon, D., Mugerauer, R., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1985; pp. 183–197. ISBN 978-94-010-9251-7. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Hummon, D.M. Community Attachment: Local Sentiment and Sense of Place. Hum. Behav. Environ. Adv. Theory Res. 1992, 12, 253–278. [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht, G. Solastalgia. Altern. J. 2006, 32, 34–36. [Google Scholar]

- Horlings, L. The Inner Dimension of Sustainability: Personal and Cultural Values. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2015, 14, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grenni, S.; Soini, K.; Horlings, L.G. The Inner Dimension of Sustainability Transformation: How Sense of Place and Values Can Support Sustainable Place-Shaping. Sustain. Sci. 2020, 15, 411–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talmage, C.A.; Hagen, B.; Pijawka, D.; Nassar, C. Measuring Neighborhood Quality of Life: Placed-Based Sustainability Indicators in Freiburg, Germany. Urban Sci. 2018, 2, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempsey, N.; Burton, M. Defining Place-Keeping: The Long-Term Management of Public Spaces. Urban For. Urban Green. 2012, 11, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safarkhani, M. Sustainable Park Model: A Qualitative Approach in Sustainability Assessment of Parks. Ph.D. Thesis, Istanbul Technical University, Istanbul, Turkey, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Baradaran Rahimi, F.; Levy, R.M.; Boyd, J.E.; Dadkhahfard, S. Human Behaviour and Cognition of Spatial Experience; a Model for Enhancing the Quality of Spatial Experiences in the Built Environment. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2018, 68, 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jóźwik, R. Architectural and Urban Changes in a Residential Environment—Implications for Design Science. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Bommel, M.N.C.; Derkzen, M.L.; Vaandrager, L. Greening for Meaning: Sense of Place in Green Citizen Initiatives in the Netherlands. Wellbeing Space Soc. 2025, 8, 100240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamai, S.; Ilatov, Z. Measuring sense of place: Methodological aspects. Tijdschr. Voor Econ. Soc. Geogr. 2005, 96, 467–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesterman, A.; Lopez, A.; Rateau, P. Sense of Place as an Attitude: Length of Residence, Landscape Values and Personal Involvement in Relation to a Brief Version of the Jorgensen and Stedman (2001) Sense of Place Scale (El Sentido de Lugar Como Actitud: Tiempo de Residencia, Valores Paisajisticos, e Implicacion Personal En La Version Breve de La Escala de Sentido de Lugar de Jorgensen y Stedman, 2001). PsyEcology 2021, 12, 356–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Peng, L.; Liu, S.; Su, C.; Wang, X.; Chen, T. Influences of Sense of Place on Farming Households’ Relocation Willingness in Areas Threatened by Geological Disasters: Evidence from China. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 2017, 8, 16–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Peng, L.; Liu, S.; Wang, X. Influences of Risk Perception and Sense of Place on Landslide Disaster Preparedness in Southwestern China. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 2018, 9, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ittelson, W.H.; Rosenblatt, D.; Proshansky, H.M.; Service, U.S.P.H.; College, B. Some Factors Influencing the Design and Function of Psychiatric Facilities: A Progress Report, December 1, 1958-November 1, 1960; Brooklyn College: Brooklyn, NY, USA, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Rapoport, A. Some Observations Regarding Man-Environment Studies. Archit. Res. Teach. 1971, 2, 4–15. [Google Scholar]

- Altman, I. Some Perspectives on the Study of Man-Environment Phenomena. Represent. Res. Soc. Psychol. 1973, 4, 109–126. [Google Scholar]

- Canter, D.V. The Psychology of Place; Architectural Press: London, UK, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Punter, P. Participation in the Design of Urban Space. Landsc. Des. 1991, 200, 24–27. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery, J. Making a City: Urbanity, Vitality and Urban Design. J. Urban Des. 1998, 3, 93–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gieryn, T.F. A Space for Place in Sociology. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2000, 26, 463–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafson, P. Meanings of Place: Everyday Experience and Theoretical Conceptualizations. J. Environ. Psychol. 2001, 21, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruenewald, D.A. Foundations of Place: A Multidisciplinary Framework for Place-Conscious Education. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2003, 40, 619–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falahat, M.S. Hess-e Makan va Avamel-e Mo’asser Bar an [Sense of Place and the Factors Shaping It]. Fine Arts J. 2006, 26, 57–66. [Google Scholar]

- Cresswell, T. Place. In International Encyclopedia of Human Geography; Kitchin, R., Thrift, N., Eds.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2009; pp. 169–177. ISBN 978-0-08-044910-4. [Google Scholar]

- Lewicka, M. What Makes Neighborhood Different from Home and City? Effects of Place Scale on Place Attachment. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scannell, L.; Gifford, R. Defining Place Attachment: A Tripartite Organizing Framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoomi, H.A.; Yazdanfar, S.-A.; Hosseini, S.-B.; Maleki, S.N. Comparing the Components of Sense of Place in the Traditional and Modern Residential Neighborhoods. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 201, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingues, R.; Gonçalves, G.; de Jesus, S. Measuring sense of place: A new place-people-time-self model. J. Spat. Organ. Dyn. 2021, 9, 239–258. [Google Scholar]

- Motalebi, G.; Khajuei, A.; Sheykholeslami, F.F. Investigating the Effective Factors on Place Attachment in Residential Environments: Post-Occupancy Evaluation of the 600-Unit Residential Complex. Int. J. Hum. Cap. Urban Manag. 2023, 8, 373–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proshansky, H.M.; Fabian, A.K.; Kaminoff, R. Place-Identity: Physical World Socialization of the Self. J. Environ. Psychol. 1983, 3, 57–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casey, E.S. Between Geography and Philosophy: What Does It Mean to Be in the Place-World? Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 2001, 91, 683–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lengen, C.; Kistemann, T. Sense of Place and Place Identity: Review of Neuroscientific Evidence. Health Place 2012, 18, 1162–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devine-Wright, P.; Clayton, S. Introduction to the Special Issue: Place, Identity and Environmental Behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 267–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Sun, X.; Liu, C.; Qiu, B. Effects of Urban Landmark Landscapes on Residents’ Place Identity: The Moderating Role of Residence Duration. Sustainability 2024, 16, 761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.; Lin, L.; Liu, S.; Xu, D.D. Interaction between Risk Perception and Sense of Place in Disaster-Prone Mountain Areas: A Case Study in China’s Three Gorges Reservoir Area. Nat. Hazards 2017, 85, 777–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCunn, L.J.; Gifford, R. Interrelations between Sense of Place, Organizational Commitment, and Green Neighborhoods. Cities 2014, 41, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, M.C.; Hernández, B. Place attachment: Conceptual and empirical questions. J. Environ. Psychol. 2001, 21, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alirhayim, R. Place Attachment in the Context of Loss and Displacement: The Case of Syrian Immigrants in Esenyurt, Istanbul. J. Urban Aff. 2025, 47, 381–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, M.; Chen, J.; Chen, Y.; Ge, Y.; Zheng, L.; Yang, S. Coupling Relationship Between Tourists’ Space Perception and Tourism Image in Nanxun Ancient Town Based on Social Media Data Visualization. Buildings 2025, 15, 1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Šegota, T. Resident Attitudes, Place Attachment and Destination Branding: A Research Framework. Tour. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 21, 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.R.; Vaske, J.J. The Measurement of Place Attachment: Validity and Generalizability of a Psychometric Approach. For. Sci. 2003, 49, 830–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokols, D.; Shumaker, S.A.; Martinez, J. Residential Mobility and Personal Well-Being. J. Environ. Psychol. 1983, 3, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suntikul, W.; Jachna, T. The Co-Creation/Place Attachment Nexus. Tour. Manag. 2016, 52, 276–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, I.S.; Krolikowski, C. Developing a Sense of Place through Attendance and Involvement in Local Events: The Social Sustainability Perspective. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2025, 50, 715–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anton, C.E.; Lawrence, C. Home Is Where the Heart Is: The Effect of Place of Residence on Place Attachment and Community Participation. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 40, 451–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrobaee, T.R.; Al-Kinani, A.S. Place Dependence as the Physical Environment Role Function in the Place Attachment. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 698, 033014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strandberg, C.; Ek Styvén, M. The Multidimensionality of Place Identity: A Systematic Concept Analysis and Framework of Place-Related Identity Elements. J. Environ. Psychol. 2024, 95, 102257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewicka, M. Place Attachment, Place Identity, and Place Memory: Restoring the Forgotten City Past. J. Environ. Psychol. 2008, 28, 209–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, J.; Ahn, J.J.; Corley, E.A. Sense of Place: Trends from the Literature. J. Urban. Int. Res. Placemaking Urban Sustain. 2020, 13, 236–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.R.; Patterson, M.E.; Roggenbuck, J.W.; Watson, A.E. Beyond the Commodity Metaphor: Examining Emotional and Symbolic Attachment to Place. Leis. Sci. 1992, 14, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemieshkaftaki, M.; Dupre, K.; Fernando, R. A Systematic Literature Review of Applied Methods for Assessing the Effects of Public Open Spaces on Immigrants’ Place Attachment. Architecture 2023, 3, 270–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, J.D.; Greenwood, D.A.; Thomashow, M.; Russ, A. 7. Sense of Place. In Urban Environmental Education Review; Russ, A., Krasny, M.E., Eds.; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 68–75. ISBN 978-1-5017-1279-1. [Google Scholar]

- Sebastien, L. The Power of Place in Understanding Place Attachments and Meanings. Geoforum 2020, 108, 204–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, M.E.; Williams, D.R. Maintaining Research Traditions on Place: Diversity of Thought and Scientific Progress. J. Environ. Psychol. 2005, 25, 361–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.R. “Beyond the Commodity Metaphor,” Revisited: Some Methodological Reflections on Place Attachment Research. In Place Attachment: Advances in Theory, Methods and Applications; Manzo, L.C., Devine-Wright, P., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 89–99. [Google Scholar]

- Gokce, D.; Chen, F. Multimodal and Scale-Sensitive Assessment of Sense of Place in Residential Areas of Ankara, Turkey. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2021, 36, 1077–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesari, E.; Peysokhan, M.; Havashemi, A.; Gheibi, D.; Ghafourian, M.; Bayat, F. Analyzing the Dimensionality of Place Attachment and Its Relationship with Residential Satisfaction in New Cities: The Case of Sadra, Iran. Soc. Indic. Res. 2019, 142, 1031–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalina, M. “A Neighbourhood of Necessity”: Creating Home and Neighbourhood within Subsidised Aged Housing in Durban, South Africa. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2021, 36, 1671–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyle, G.T.; Theodori, G.L.; Absher, J.D.; Jun, J. The Influence of Home and Community Attachment on Firewise Behavior. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2010, 23, 1075–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tester, G.; Ruel, E.; Anderson, A.; Reitzes, D.C.; Oakley, D. Sense of Place among Atlanta Public Housing Residents. J. Urban Health 2011, 88, 436–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Jin, M.; Zuo, Y.; Ding, P.; Shi, X. The Effect of Soundscape on Sense of Place for Residential Historical and Cultural Areas: A Case Study of Taiyuan, China. Buildings 2024, 14, 1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guz, A.N.; Rushchitsky, J.J. Scopus: A System for the Evaluation of Scientific Journals. Int. Appl. Mech. 2009, 45, 351–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mongeon, P.; Paul-Hus, A. The Journal Coverage of Web of Science and Scopus: A Comparative Analysis. Scientometrics 2016, 106, 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.K.; Singh, P.; Karmakar, M.; Leta, J.; Mayr, P. The Journal Coverage of Web of Science, Scopus and Dimensions: A Comparative Analysis. Scientometrics 2021, 126, 5113–5142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Q.N.; Fàbregues, S.; Bartlett, G.; Boardman, F.; Cargo, M.; Dagenais, P.; Gagnon, M.-P.; Griffiths, F.; Nicolau, B.; O’Cathain, A.; et al. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) Version 2018 for Information Professionals and Researchers. Educ. Inf. 2018, 34, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gokce, D.; Kickert, C. What If “Sense of Place” Is Already Strong? An in-Depth Investigation in an Award-Winning American Neighbourhood. Urban Des. Int. 2024, 29, 39–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghafourian, M.; Hesari, E. Evaluating the Model of Causal Relations Between Sense of Place and Residential Satisfaction in Iranian Public Housing (The Case of Mehr Housing in Pardis, Tehran). Soc. Indic. Res. 2018, 139, 695–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadizadeh, A.; Nourtaghani, A. Sense of Place in the Process of Changing the Configuration and Activity of Rural Housing Types. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2022, 21, 1431–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, B.; Stedman, R. A Comparative Analysis of Predictors of Sense of Place Dimensions: Attachment to, Dependence on, and Identification with Lakeshore Properties. J. Environ. Manag. 2006, 79, 316–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baylan, E.; Aşur, F.; Şehrıbanoğlu, S. Sense of Place and Satisfaction with Landscaping in Post-Earthquake Housing Areas: The Case of Edremit Toki-Van (Turkey). Archit. City Environ. 2018, 13, 31–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anacio, D.B.; Hilvano, N.F.; Burias, I.C.; Pine, C.; Nelson, G.L.M.; Ancog, R.C. Dwelling Structures in a Flood-Prone Area in the Philippines: Sense of Place and Its Functions for Mitigating Flood Experiences. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2016, 15, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costlow, K.; Parmelee, P.A.; Choi, S.L.; Roskos, B. When Less Is More: Downsizing, Sense of Place, and Well-Being in Late Life. J. Environ. Psychol. 2020, 71, 101478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soleimani, M.; Shushtari, S. The Impact of Behavioral Types on the Sense of Place in the Front Yard: A Structural Equation Modeling. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2024, 39, 317–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandauko, E.; Arku, G.; Matamanda, A.; Asare, A.; Akyea, T. “The Unwavering Bond”: Examining the Sense of Place in Harare’s Informal Urban Neighbourhoods. Can. J. Afr. Stud. 2024, 58, 657–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Manen, M. Phenomenology of Practice: Meaning-Giving Methods in Phenomenological Research and Writing, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2023; ISBN 978-1-003-22807-3. [Google Scholar]

- Ebbini, G.W.; Bleibleh, S. GROW-J: An Empirical Study of Social Sustainability, Sense of Place, and Subjective Well-Being in Jordanian Housing Development. Front. Sustain. Cities 2024, 6, 1448061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gokce, D.; Chen, F. Sense of Place in the Changing Process of House Form: Case Studies from Ankara, Turkey. Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2018, 45, 772–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acedo, A.; Painho, M.; Casteleyn, S. Place and City: Operationalizing Sense of Place and Social Capital in the Urban Context. Trans. GIS 2017, 21, 503–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shami, H.W.; Al-Alwan, H.A.S.; Abdulkareem, T.A. Cultural Sustainability in Urban Third Places: Assessing the Impact of “Co-Operation in Science and Technology” in Cultural Third Places. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2024, 15, 102465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masterson, V.A.; Enqvist, J.P.; Stedman, R.C.; Tengö, M. Sense of Place in Social–Ecological Systems: From Theory to Empirics. Sustain. Sci. 2019, 14, 555–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, H.-M.; Su, J.-Y.; Wang, C.-H.; Kiatsakared, P.; Chen, K.-Y. Place Attachment and Environmentally Responsible Behavior: The Mediating Role of Destination Psychological Ownership. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Article | Year | Dimensions of Human–Place Interaction |

|---|---|---|

| [77] | 1960 | Perceptual area, Expressive area, Aesthetic values of a culture, Adaptive area, Instrumental area, Integrative area, Ecological |

| [78] | 1971 | Perception and Cognition: Cultural Variability Vision and Complexity, Images, Values, and Schemata Design and Behavior: Crowding, Environmental Quality, Propinquity, Friendship and Interaction, Privacy Designers as form givers: Designers and the public, Determinants of spatial organization |

| [79] | 1973 | Mechanistic model, Perceptual–cognitive–motivational model, Behavioral model, Ecological–social systems model |

| [5] | 1976 | Insideness, Outsideness, Existential Experience |

| [80] | 1977 | Form, Imagination, Activities |

| [81] | 1991 | Form, Meaning, Activities |

| [20] | 1992 | Cognitive, Emotional, Behavioral |

| [82] | 1998 | Physical Setting, Meaning, Activities |

| [83] | 2000 | Geographic Location, Material Form, Investment with Meaning and Value |

| [84] | 2001 | Self, Others, Environment |

| [10] | 2001 | Cognitive, Affective, Conative |

| [85] | 2003 | Perceptual, Sociological, Ideological, Political, Ecological |

| [86] | 2006 | Physical Features, Meaning, Individual Features, Activities |

| [87] | 2009 | Location, Locale (material setting), Sense of Place |

| [88] | 2010 | Physical, Social, Socio-demographic |

| [89] | 2010 | Person, Process, Place |

| [90] | 2015 | Demographic characteristics, Physical and visual features, Social characteristics and activities, Meanings, Ecosystem |

| [91] | 2021 | Place, People, Time, Self |

| [92] | 2023 | Time, Objective physical characteristics, Subjective physical characteristics, Individual characteristics. |

| [55] | 2024 | Symbolism, Purpose, Identity, Relation, Emotion |

| Place Identity * | Place Attachment | Place Dependence | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitive | Self-categorization, Centrality of identity, Self-fit, Self-meanings, Self-congruity | Evaluative beliefs, Memories, Symbolic meaning, Personal significance | Perceived utility, Functional fit, Goal support, Contextual advantages |

| Affective | Affective attachment, Centrality of affect, Self-merging, Motivational drivers | Feelings of belonging, Affection, Rootedness, Emotional security | Feelings of irreplaceability, Emotional reliance, Necessity-based attachment, Affective commitment to utility |

| Conative | Behavioral attachment, Preferences, Functional evaluations | Continued interaction (routine/emotional familiarity), Intention to stay or return, Protective actions, Proximity-seeking behavior | Continued use, Avoidance of alternatives, Functional loyalty, Place-anchored behavioral choices |

| Article | Term Used | Indicators |

|---|---|---|

| [100] | Place attachment = Sense of place | Social attachment, Physical attachment |

| [119] | Place attachment = Sense of place | Place identity, Place dependence, Nature bonding, Social bonding, Belonging, Familiarity, Social interaction |

| [120] | Place attachment = Sense of place | Place identity, Place affect, Place dependence, Social bonding |

| [121] | Place attachment = Sense of place | Place identity, Place dependence |

| [122] | Place attachment (indirectly sense of place) | Affective attachment, Place identity, Place dependence |

| [92] | Sense of place attachment (indirectly sense of place) | Place dependence, Place identity, Process. |

| [123] | Sense of place | Place attachment, Community attachment |

| [124] | Sense of Place | Place attachment, Place identity |

| Article | Theme | Region/Country | Housing Context/Settlement Type/Occupancy Type | Physical and Spatial Characteristics | Method | SOP Indicators (n) | Additional SOP Indicator (n) | Predictor Variables (n) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quantitative | ||||||||||

| Study Design-Sample Size (n) | Data Collection | Data Analysis/Software | ||||||||

| [130] | High-quality housing and SOP | North America /Elmwood Village, Buffalo, New York, USA | Urban/Mixed housing types (single-story, duplexes, apartments)/Permanent | Historical architectural diversity; vegetated streetscapes; moderate enclosure (sky views, building scale, tree cover); park access | Questionnaire 5-point Likert scale/(202) | In person surveys | Regression analysis, Correlation analysis, Descriptive statistics/software not specified; likely SPSS | PI (6) PA (3) PD (5) | Nature Bonding (5) | Socio-demographic (5) Neighborhood scale (3) Street scale (2) Building scale (3) |

| [131] | Public Housing and SOP | Middle East & North Africa /Pardis, Tehran, Iran | Suburban/Multi-story apartment blocks/Permanent | Regular layout, identical blocks; limited public services; external transport access; lack of local transport and recreational and communal spaces | Questionnaire 5-point Likert scale/330) | In person surveys | Structural equation modeling, Descriptive statistics, Correlation analysis/SPSS v22, AMOS v22 | PI (5) PA (4) PD (6) | SOP (3) | Sociodemographic (8) Residential Satisfaction (4) |

| [133] | Waterfront Housing and SOP | North America /Vilas County-northern Wisconsin, USA | Rural/Detached single-family houses/Mixed (Permanent and Seasonal) | Natural landscape with native vegetation and lake; amenity-based, low-density residential setting | Questionnaire 5-point Likert scale/(290) | Mail survey | Structural equation modeling, Descriptive statistics, Correlation analysis/SPSS v10.0.5, LISREL 8.70 | PI (4) PA (4) PD (4) | None | Sociodemographic Factors (2) Behavioral Engagement (2) Property Development Index (1) (Summed from 9 physical features of the property) Attitude Toward Shoreline Housing (4) Attitude Toward Natural Vegetation (3) Lake Importance (3) |

| [134] | Post-Disaster Housing and SOP | Europe & Central Asia /Edremit, Van, Turkey | Urban/Apartment blocks (3–4 stories)/Permanent | Regular layout, identical blocks; concrete-frame structures; green spaces, playgrounds, public facilities | Questionnaire 5-point Likert scale/(235) | In person surveys | Structural equation modeling, Descriptive statistics/R software, SPSS v24 | PI (4) PA (4) PD (4) | None | Socio-demographic (10) Satisfaction with Landscaping: Effect of planting on the local climatic conditions (5) Open-green spaces and scenery (4) Landscape furniture/equipment (4) External connections and social services (5) Accessibility and roads within the residential area (3) |

| Article | Theme | Region/Country | Housing Context/Settlement Type/Occupancy Type | Physical and Spatial Characteristics | Method | SOP Indicators (n) | Additional SOP Indicator (n) | Predictor Variables (n) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qualitative | ||||||||||

| Study Design/Sample Size (n) | Data Collection | Data Analysis/Software | ||||||||

| [138] | Informal Housing and SOP | Sub-Saharan Africa (Southern Africa)/ Hopley and Hatcliffe Extension, Harare, Zimbabwe | Peri-urban/Self-built single-story housing/Permanent | Haphazard layout; overcrowded and poor-quality housing constructed from mixed materials (wood, tin, bricks, polythene); built without planning permission; limited infrastructure; disconnected from formal urban systems | Open-ended questions/Four focus groups (two per settlement), 8 participants each (32) | In person Focus group discussions | Phenomenological thematic analysis following Van Manen’s [139] three-step approach (holistic, selective, detailed) | PI, PA, PD (11 questions) | None | Length of residence, social networks, shared histories, housing transformation, access to services, autonomy, neighborhood reputation, future prospects (all discussed qualitatively, not as structured variables) |

| [140] | Retrofitted Sustainable Housing and SOP | Middle East & North Africa /Qasr Al-Hallabat and Ajloun, Jordan | Semi-rural/Retrofitted single-family housing/Permanent | Structured layout; formally constructed housing retrofitted with sustainable features (solar panels, energy-efficient windows); includes front yards, gardens, and occasional second-story extensions; culturally responsive design; limited but improving infrastructure access. | Open-ended questions/27 households (16 in Qasr Al-Hallabat, 11 in Ajloun)/(36) | In person interview, Direct observation, and visual ethnography | IPA with thematic coding and triangulation/NVivo | PI, PA, PD (11 questions) | None | Social bonding and networks, cultural continuity, home-based enterprises, community projects, housing retrofitting (solar panels, energy-efficient windows, gardens), access to essential services, local traditions, self-driven modifications (all discussed qualitatively, not as structured variables) |

| Article | Theme | Region/Country | Housing Context/Settlement Type/Occupancy Type | Physical and Spatial Characteristics | Method | SOP Indicators (n) | Additional SOP Indicator (n) | Predictor Variables- (n) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mixed (Quantitative and Qualitative) | ||||||||||

| Study Design/Sample Size (n) | Data Collection | Data Analysis/Software | ||||||||

| [132] | Rural Housing Typology and SOP | Middle East & North Africa /Ashkor, Guilan, Iran | Rural/Indigenous and Engineered Single- and two-story detached houses/Permanent | Indigenous: Timber/brick, organic layout, high integration Engineered: Concrete/brick, compartmentalized, lower integration | Interviews, Questionnaire 7-point Likert scale/(382) | In-person surveys and interviews | Quantitative data: Descriptive statistics, Inferential statistical analysis, Space syntax analysis/R software, UCL Depthmap Qualitative data: Content analysis using open coding | PI (4) PA (5) PD (5) | Aesthetics (4) Nature Bonding (6) Familiarity (2) Sense of Belonging (4) Social Bonding (4) Social Interactions (5) Privacy (9) | Type of housing, Spatial configuration, Activity pattern |

| [135] | Disaster-Resilient Housing and SOP | East Asia & Pacific /Tadlac, Los Baños, Laguna, Philippines | Rural/Single- and two-story houses/Permanent | Bamboo/wood and concrete and mixed housing Flood-prone settlements | Interviews, Questionnaire 4-point Likert scale/(71) | In-person surveys and interviews | Quantitative data: Regression analysis, Descriptive statistics/SPSS v2 Qualitative data: Phenomenological analysis with Experience Use History (EUH) and thematic interpretation | PI (4) PA (4) PD (4) | None | Socio-demographic (10) Housing characteristics (9) |

| [136] | Late-Life Housing Downsizing and SOP | North America /Multi-state, USA | Urban-Suburban/Apartments or attached units/Permanent | Smaller, low-maintenance homes with accessibility considerations; ease of daily functioning; proximity to services; designed or selected for aging-related needs | Questionnaire 5-point Likert scale/(235) | Phone interview, in person survey | Quantitative data: Structural equation modeling, Descriptive statistics, Correlation analysis, Regression analysis/SPSS v25, PROCESS macro v3.0 Qualitative data: Descriptive content analysis using predefined coding schema | PI (4) PA (4) PD (4) | None | Sociodemographic (8) Relocation factors (7) Perceived Health (6) Push–Pull Factors (24) Relocation controllability (9) Relocation outcomes (7) |

| [137] | Urban Housing Threshold and SOP | Middle East & North Africa /Ahwaz, Iran | Urban/Single-story houses with front yards/Permanent | Middle-class residential context/One-sided house typology/Private front yards oriented north–south/Open yard between house and street (no courtyard)/Used for social, leisure, and functional activities | Interviews, Questionnaire 5-point Likert scale/(248 survey, 16 interviews) | In-person interviews, phone interviews, and online survey | Quantitative data: Structural equation modeling/ SmartPLS 3 Qualitative data: Grounded theory coding and thematic content analysis with triangulation | PI (2) PA (3) PD (3) | None | Autonomous Behavior (5) Normative Behavior (6) Controlled Behavior (6) |

| Article | Place Identity | Place Attachment | Place Dependence | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitive | Affective | Conative | Cognitive | Affective | Conative | Cognitive | Affective | Conative | |

| [133] | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| [134] | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| [130] | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| [131] | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| [136] | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| [138] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| [135] | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| [137] | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| [132] | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| [140] | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Place Identity | Literal Count | Place Attachment | Literal Count | Place Dependence | Literal Count | Overall Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitive | Self-categorization | 2 | Evaluative beliefs | 5 | Perceived utility | 1 | |

| Centrality of identity | 1 | Memories | 1 | Functional fit | 2 | ||

| Self-fit | 1 | Symbolic meaning | 2 | Goal support | 2 | ||

| Self-meanings | 3 | Personal significance | 1 | Contextual advantages | 1 | ||

| Self-congruity | 2 | ||||||

| Total | 9 | 9 | 6 | 24 | |||

| Affective | Affective attachment | 3 | Belonging | 2 | Feelings of irreplaceability | 1 | |

| Centrality of affect | 1 | Affection | 1 | Emotional reliance | 1 | ||

| Self-merging | 1 | Rootedness | 1 | Necessity-based attachment | 2 | ||

| Motivational drivers | 1 | Emotional security | 1 | Affective commitment to utility | 2 | ||

| Total | 6 | 5 | 6 | 17 | |||

| Conative | Behavioral attachment | 5 | Continued interaction | 2 | Continued use | 3 | |

| Preferences | 3 | Intention to stay or return | 2 | Avoidance of alternatives | 2 | ||

| Functional evaluations | 4 | Protective actions | 2 | Functional loyalty | 3 | ||

| Proximity-seeking behavior | 2 | Place-anchored behavioral choices | 3 | ||||

| Total | 12 | 8 | 11 | 31 | |||

| Overall total | 27 | 22 | 23 | 72 |

| Themes | Sub-Themes | Description/Representative Factors | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical and Spatial | Design, Layout and Spatial Configuration | Housing Environment | Spatial clarity and enclosure (legibility, density); architectural coherence; pedestrian-friendly and human-scaled design |

| Housing Unit | Housing type and size; amenity-based layout; spatial integration; privacy; ease of maintenance | ||

| Functional Fit and Utility | Housing Environment | Mobility and accessibility; proximity to essential services; availability of social and recreational spaces; support for daily routines | |

| Housing Unit | Flexibility in use; adaptability; structural safety and durability; potential for personalization | ||

| Environmental | Natural Elements | Presence of native vegetation; proximity to water bodies and natural landmarks; minimal intervention in natural state | |

| Environmental Qualities | Microclimatic comfort; visual quality of green and open spaces; environmental safety and comfort; culturally significant and natural soundscapes | ||

| Social | Social Dynamics | Kinship and neighbor ties; shared history; community recognition and pride; emotional security through social continuity; mutual support networks | |

| Life Stage and Socio-demographic Factors | Age and length of residence; control over relocation; household composition and vulnerable groups; socio-economic background; Multigenerational continuity | ||

| Cultural | Symbolic and Cultural Alignment | Home as a symbolic extension of self; cultural and traditional congruence expressed through collective memory, communal, and ritual practices | |

| Economic | Financial Factors | Housing affordability; use of housing for livelihood activities (home-based enterprises); cost-sensitive relocation decisions. | |

| Institutional | Tenure and Land Use Regulations | Security of tenure; autonomy in land use decisions; clarity of property rights and regulatory frameworks | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Safarkhani, M. Space to Place, Housing to Home: A Systematic Review of Sense of Place in Housing Studies. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6842. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156842

Safarkhani M. Space to Place, Housing to Home: A Systematic Review of Sense of Place in Housing Studies. Sustainability. 2025; 17(15):6842. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156842

Chicago/Turabian StyleSafarkhani, Melody. 2025. "Space to Place, Housing to Home: A Systematic Review of Sense of Place in Housing Studies" Sustainability 17, no. 15: 6842. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156842

APA StyleSafarkhani, M. (2025). Space to Place, Housing to Home: A Systematic Review of Sense of Place in Housing Studies. Sustainability, 17(15), 6842. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156842