Abstract

As sustainability becomes a strategic priority across global financial services, its implementation in emerging insurance markets remains insufficiently understood. This study explores the integration of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) principles within Saudi Arabia’s insurance sector, combining content analysis of corporate disclosures with qualitative insights from industry stakeholders. The research investigates how insurers embed ESG principles into their operations, the development of sustainable insurance products, and their perceived financial and regulatory implications. The findings reveal gradual progress in ESG integration, primarily driven by governance reforms aligned with national development agendas, while social and environmental dimensions remain comparatively underdeveloped. Stakeholders identify regulatory ambiguity, data limitations, and technical capacity as persistent barriers, but also point to increasing investor and consumer interest in sustainability-aligned offerings. This study offers policy and managerial recommendations to advance ESG principle adoption, emphasizing standardized disclosures, capacity-building, and product innovation. It contributes to the limited empirical literature on ESG principles in Middle Eastern insurance markets and highlights the sector’s potential role in promoting inclusive and sustainable finance.

1. Introduction

Over the past decade, sustainability has evolved into a foundational principle in global financial systems, with the insurance sector playing a critical role in promoting environmental stewardship, social responsibility, and ethical governance. The need to integrate sustainability into insurance models is particularly urgent given the sector’s inherent function in risk management and long-term capital allocation, as well as its capacity to influence client behavior and societal resilience [1].

The financial industry is increasingly recognizing that the integration of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) principles is not merely a matter of compliance but a strategic imperative. Insurers are emerging as key actors in the transition toward sustainable development by embedding ESG principles into underwriting, investment policies, and operations [2,3]. This trend is reinforced by initiatives such as the UNEP FI’s Principles for Sustainable Insurance [4], which highlight the role of insurers in fostering a sustainable, low-carbon, and inclusive economy.

In Saudi Arabia, this global momentum intersects with national economic restructuring under Vision 2030, which aims to diversify the economy and enhance long-term resilience. The insurance sector has been identified as a catalyst for sustainable growth, particularly growth through the development of inclusive products and Takaful-based models that align with Islamic financial principles [5,6]. However, the adoption of ESG principles in the Saudi insurance market reflects uneven progress. While governance practices have improved due to regulatory pressure from entities like the Saudi Central Bank (SAMA) and the Capital Market Authority (CMA), the environmental and social dimensions remain underdeveloped and inconsistently reported [3].

Several challenges persist. These include regulatory ambiguity, capacity constraints among smaller firms, and a lack of standardized ESG metrics [2]. Despite these hurdles, there are promising opportunities such as the growth of climate-conscious underwriting and inclusive insurance programs and rising public awareness of sustainability, which suggests that the sector is approaching a tipping point in its ESG maturity.

Takaful insurers, in particular, hold significant potential to bridge Islamic ethical finance and ESG standards. However, many firms have yet to fully leverage this alignment due to weak disclosure frameworks and limited product innovation [7]. Meanwhile, Vision 2030 has accelerated digital transformation and transparency expectations across the sector, further reinforcing the strategic value of the ESG principles’ integration.

While the integration of ESG principles has been widely explored in developed financial markets, emerging economies remain under-researched, despite their increasing participation in global capital markets. Saudi Arabia presents a compelling case due to the top-down nature of its economic transformation under Vision 2030, the state-led ESG reforms carried out by the Saudi Central Bank (SAMA), and the strategic push toward financial sector development. Unlike many emerging markets where the implementation of ESG principles is fragmented or peripheral, Saudi Arabia has institutionalized ESG principles through explicit policy mandates and evolving regulatory guidelines [8], This state-orchestrated model creates a novel environment in which the adoption of ESG principles may be more aligned with strategic governance than market-driven incentives, offering a unique opportunity to evaluate ESG impacts under a hybrid economic governance regime

There is a notable lack of empirical studies that integrate both financial performance metrics and stakeholder perspectives to evaluate the impact of ESG principles. To address this gap, this study is guided by two central research questions: To what extent have insurance firms in Saudi Arabia incorporated ESG principles and sustainable product innovation into their operations? What financial, regulatory, and strategic benefits are associated with ESG integration in the Saudi insurance context?

By addressing these questions, this paper contributes to the expanding but underdeveloped body of literature on ESG principles in emerging markets. It also offers practical insights for policymakers, regulators, and insurance practitioners seeking to align environmental and social outcomes with national economic diversification goals.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 presents a critical review of the relevant literature and theoretical frameworks. Section 3 outlines the research methodology, detailing the mixed-methods approach that combines econometric modeling and qualitative analysis. Section 4 reports and interprets the empirical findings. Section 5 discusses policy implications and strategic insights, concludes this paper and suggests directions for future research.

2. Literature Review

The integration of ESG criteria within the insurance sector has evolved from a peripheral concern to a central strategic objective. This transformation is driven by global pressures to implement sustainable finance and the increasing recognition of insurers as agents of resilience, investment stability, and risk innovation. Integration of ESG principles supports insurers in aligning underwriting, investment, and operational practices with long-term societal and environmental goals [4,9].

ESG principles are no longer seen as a voluntary corporate gesture but as a strategic necessity, particularly in industries exposed to long-term risk cycles like insurance [9]. As global climate and societal risks become increasingly systemic, insurers are positioned not only as risk carriers but as influential agents in guiding societal adaptation and resilience. The UNEP FI’s Principles for Sustainable Insurance (2022) [4] highlight how the integration of ESG principles across underwriting, investments, and internal operations can facilitate long-term resilience and sustainability.

Stakeholder theory [10] is central to understanding ESG principles in insurance. It posits that firms must respond to the needs of all stakeholders, not just shareholders. ESG frameworks operationalize this theory by translating social and environmental obligations into business practices.

Empirical evidence demonstrates a strong correlation between ESG performance and superior financial outcomes. Firms with advanced ESG profiles typically benefit from lower costs of capital and improved risk-adjusted returns [11]. This relationship holds particular relevance for insurers due to their exposure to long-horizon liabilities and regulatory scrutiny. ESG-aligned insurers may also have reduced operational and reputational risks, which supports sustainable profitability [12,13].

Resource-based view (RBV) theory [14] offers a compelling rationale: ESG capabilities constitute intangible assets that are valuable, rare, and difficult to imitate. These assets provide insurers with competitive advantages in risk selection, capital sourcing, and market reputation.

Empirical evidence suggests that firms with stronger ESG performance often enjoy lower capital costs and superior risk-adjusted returns, which enhances their financial competitiveness [11]. ESG-aligned insurers also benefit from enhanced reputational capital and stakeholder trust, which contribute to long-term viability and market differentiation [13]. Nevertheless, the integration of ESG principles remains hindered by fragmented standards, inconsistent data quality, and varying levels of ESG maturity across global and regional markets [15].

Recent bibliometric analyses [16] highlight the geographical skew of ESG scholarship toward North America and Europe, with limited representation from MENA markets. This reinforces the call for regionally grounded ESG research that reflects diverse regulatory, cultural, and institutional conditions.

Innovative sustainable insurance products have emerged to internalize and mitigate environmental and social risks. These include flood insurance linked to resilience upgrades, usage-based auto insurance, and climate-informed crop insurance, all of which align premiums more closely with dynamic risk exposures [17]. Such models not only support client sustainability behavior but also help insurers improve their portfolio risk profiles. Furthermore, socially oriented products like microinsurance and inclusive health coverage have proven effective in reducing vulnerabilities and enhancing financial inclusion, especially in underserved populations (World Bank [18]). Sustainable insurance products internalize ESG risk by incentivizing risk-reducing behavior among clients. For instance, insurance linked to resilience upgrades (e.g., flood-resistant infrastructure), pay-as-you-drive auto insurance, or climate-smart crop insurance align premiums with actual, real-time risk exposure [17]. These products not only manage insurer risks but also influence customer behavior, advancing broader societal resilience.

However, the success of these products is often contingent on contextual factors such as financial literacy, cultural norms, and distribution infrastructure [19].

Despite its benefits, the integration of ESG principles is often hampered by fragmented regulatory frameworks, inconsistent data quality, and heterogeneous ESG maturity across geographies [15]. For insurers, this creates difficulties in standardizing sustainability practices across underwriting and investment portfolios. A lack of reliable data also limits the ability to assess and price ESG-related risks effectively.

Giráldez-Puig et al. [20] extend this relationship by showing that ESG controversies are predictive of higher insolvency risk in the insurance industry, underscoring the relevance of ESG performance as a proxy for financial stability.

In emerging markets, the integration of ESG principles is shaped by a different set of institutional logics compared to developed economies. As noted by DiMaggio and Powell [21], regulatory and normative isomorphism can lead firms to adopt ESG practices not necessarily in response to market demand but to align with state expectations and legitimacy pressures. In Saudi Arabia, this is particularly salient given the government’s role in shaping corporate governance through regulatory mandates and the Vision 2030 framework. Moreover, ESG initiatives in such contexts are not only driven by global investor pressures but also serve developmental goals, such as economic diversification, social inclusion, and environmental resilience. Drawing on the development finance literature [15], the adoption of ESG practices in emerging markets can act as both a modernization tool and a reputational signal to international investors.

Regionally, Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 positions the insurance sector as a vital pillar in achieving national sustainability and economic diversification. The issuance of the “Guidelines on ESG Reporting for Financial Institutions” by the Saudi Central Bank (SAMA) in 2021 reflects a policy transition from voluntary to institutionalized alignment with ESG principles [8]. Additional mandates by entities such as the National Center for Environmental Compliance and the Public Investment Fund require transparency in carbon disclosure and ESG-aligned investment practices. Despite these advancements, local insurers often confront knowledge deficits, inconsistent reporting frameworks, and operational inertia [22].

An additional layer of complexity and opportunity is introduced by Takaful insurance, which integrates Shariah principles into financial design. Scholars argue that the ethical tenets underpinning Takaful such as risk-sharing, fairness, and community welfare are inherently compatible with ESG values, offering a culturally embedded framework for sustainability in Islamic markets [7].

While global research supports a positive correlation between ESG performance and financial outcomes, the literature specific to Middle Eastern and Saudi Arabian insurance markets remains sparse. Recent works [16,20] indicate that ESG practice disclosure in the region is still in its infancy, with adoption rates varying significantly across firms. Moreover, the lack of mixed-methods research that integrates quantitative performance metrics with qualitative stakeholder insights represents a critical gap.

This study aims to bridge that gap by applying an integrative methodological framework—merging econometric analysis with thematic insights from executive interviews and consumer focus groups. This dual approach provides both breadth and depth in evaluating the impacts of ESG practices in a transitional insurance environment.

3. Methodology

This study applies a sequential explanatory mixed-methods approach. First, a quantitative analysis using panel data econometrics investigates the relationship between ESG performance and financial outcomes among Saudi insurers. Then, qualitative data from interviews and focus groups are used to explain and contextualize the quantitative findings. This combination enhances both the internal validity and policy relevance of this study [23].

3.1. Sample Selection

The empirical sample for this study comprises 20 out of the 28 licensed insurance companies operating in Saudi Arabia, selected based on the availability and consistency of their ESG-related disclosures over a 10-year panel period from 2015 to 2024. The inclusion criterion required firms to have at least partial annual ESG data across environmental, social, or governance domains in their public filings or corporate literature. This selection process ensures longitudinal validity and enables fixed-effects panel estimation by minimizing data imbalance, a methodologically robust approach in panel econometrics [24].

This decision reflects both practical and theoretical considerations. First, ESG practice disclosure in Saudi Arabia is not uniformly mandated across all firms, which was especially true before the Saudi Central Bank (SAMA)’s ESG Reporting Guidelines were introduced in 2021. As a result, not all insurers produce structured sustainability data, particularly smaller or Takaful-focused companies, which tend to have limited reporting capacity [3]. By focusing on firms with consistent disclosures, this study mitigates data heterogeneity and missingness bias, ensuring more reliable estimation of ESG practice performance linkages.

The ESG, financial, and control variables were drawn from four primary sources:

- -

- Annual reports (2015–2024).

These serve as the primary source for financial performance indicators such as return on assets (ROA), premium growth, and loss ratios. Annual reports also include board structures, risk committees, and Sharia compliance sections used in governance scoring;

- -

- Standalone sustainability reports

Where available, these were used to extract detailed disclosures on environmental practices (e.g., energy usage, carbon reporting) and social initiatives (e.g., inclusion and employee well-being). These reports became more prevalent after 2020 following increasing regulatory attention to ESG practices;

- -

- Tadawul exchange filings

Publicly listed insurers are required to disclose investor information, including ESG-relevant data, such as corporate governance structures, shareholder resolutions, and risk exposures. Tadawul’s evolving ESG portal and listing requirements facilitated access to structured disclosures;

- -

- Third-party industry reports

Reports from auditing and consultancy firms such as KPMG, Fitch Ratings, and Albilad Capital were used to supplement data gaps, especially for benchmarking ESG practices, sector risk outlooks, and estimating ESG score components not directly disclosed in primary documents. These sources also provided insights into Takaful-specific practices and regulatory compliance trends.

This multi-source approach ensures triangulation, increases data credibility, and allows for cross-validation of ESG scores, which is a critical step given the voluntary and often inconsistent nature of ESG practice reporting in emerging markets like Saudi Arabia [15].

The qualitative component includes 18 semi-structured interviews with CEOs, CROs, and representatives from the Saudi Central Bank (SAMA). Additionally, three consumer focus groups were conducted in Riyadh and Jeddah, with a total of 24 participants. Interview guides were developed using the Principles for Sustainable Insurance (PSI) framework. NVivo software was employed for coding and theme extraction.

3.2. Variable Definition and Measurement (Table 1)

To ensure consistency across firms and over time, all ESG scores were manually derived by applying a uniform scoring matrix based on the GRI and SASB standards. Indicators were coded using standardized definitions and assessed using documentary evidence (e.g., carbon disclosures, board structure, diversity metrics) from each firm’s filings. Only data that were observable, comparable, and replicable across the sample were used. The composite ESG score thus reflects a harmonized and contextually adapted construct, which reduces the impact of the inconsistencies that are often found in third-party ESG ratings. This mitigates the divergence problem documented in the literature and enhances the internal validity of the ESG-performance relationship under study [11,15].

Table 1.

Variable definition and measurement.

Table 1.

Variable definition and measurement.

| Variable | Definition | Measurement |

|---|---|---|

| ROA | Profitability indicator | Net income/total assets (annual reports) |

| Loss Ratio (LR) | Underwriting performance | Claims incurred/premiums earned (SAMA) |

| Premium Growth | Growth in gross written premiums | (%Δ GWP year over year) from financial statements %Δ GWP |

| ESG Score | Composite score of environmental, social, governance | Custom matrix (0–5 scale per variable) based on GRI, SASB standards |

| SIZE | Firm size | Natural log of total assets (Tadawul disclosures) |

| AGE | Company age | Years since license issued (SAMA register) |

Source: Author’s elaboration.

The ESG scoring methodology used in this study, comprising 12 variables across three pillars (Environmental, Social, and Governance), with scoring on a 0–5 scale and differential weights (E: 40%, S: 30%, G: 30%), draws its foundation from both global sustainability disclosure standards and contextual adaptations that are both relevant to emerging markets like Saudi Arabia and consistent with prior ESG evaluation methodologies [4,11]. The final ESG score is calculated using a weighted average, with a 40% weight being assigned to the environmental dimension and 30% each to the social and governance dimensions. The environmental pillar receives the highest weight due to the elevated exposure of Saudi Arabia to climate-related risks, including extreme temperatures, flooding, and dust storms, factors that are increasingly affecting actuarial models and underwriting decisions. Additionally, Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 and the Saudi Green Initiative have placed environmental resilience and decarbonization at the core of the national development agenda. Insurance firms are therefore expected to lead in climate risk management and sustainable investing. This prioritization is consistent with the OECD’s recommendation to contextualize ESG weights based on national sustainability imperatives [9,15]. The social pillar is weighted at 30% to reflect both its importance and its relative underdevelopment within Saudi Arabia’s insurance sector. Despite regulatory efforts to promote inclusive insurance, such as expanding micro-Takaful and universal health coverage, social disclosures remain sparse and often qualitative [5]. The 30% allocation balances the importance of social equity with the current disclosure maturity level. Governance is weighted at 30%, slightly below its prominence in traditional ESG frameworks where it often receives equal or higher weighting. This adjustment reflects two contextual factors: (i) Saudi insurers have made substantial progress in corporate governance compliance due to pressure from the Saudi Central Bank (SAMA) and the Capital Market Authority, and (ii) governance disclosures tend to be more uniform and prescriptive, thereby requiring less discriminatory weight in the composite score. Nevertheless, governance remains essential for risk oversight and transparency and is robustly represented in the score.

The formula for the ESG score is as follows:

where:

- = Composite ESG score for firm I;

- = Average score of environmental indicators (e.g., carbon reporting, green underwriting);

- = Average score of social indicators (e.g., diversity, financial inclusion);

- = Average score of governance indicators (e.g., board independence, audit quality);

Table 2 presents the 12 indicators used to construct the composite ESG score, which is categorized into environmental (E), social (S), and governance (G) pillars. Each indicator is scored on a 0–5 scale based on observable disclosures. The scoring is manual and harmonized across firms and years using standardized definitions adapted from GRI and SASB frameworks. The overall ESG score is calculated using a weighted average: environmental (40%), social (30%), and governance (30%).

Table 2.

ESG indicator: definitions, sources, and scoring rules.

3.3. Econometric Design

We estimate the linkage between ESG performance and firm profitability utilizing the fixed-effect panel regression as shown in Table 2. We have chosen this particular method because of its following advantages. First, the fixed-effects framework pairs well with robust standard errors clustered at the firm level, which corrects for within-firm autocorrelation and heteroskedasticity, improving the reliability of its inference; each insurer differs in size, risk bearing capacity, and investment strategy. Second, it reduces bias from unobserved, time-invariant omitted variables, which could otherwise skew the estimated relationship between ESG and ROA. This aligns with recommendations in the ESG-finance literature, such as [11,25] who advocate for fixed-effects in longitudinal ESG studies to ensure causal inference robustness.

where:

- ROA = Return on assets (net income/total assets);

- ESG = Composite ESG score (0–5 scale);

- SIZE = Firm size (ln of total assets);

- AGE = Years since license issued;

- YEAR = Time fixed effects;

- μᵢ = Firm-specific effects;

- εᵢₜ = Error term.

Prior to estimating the main panel regression model, a series of diagnostic tests were conducted to ensure the robustness and validity of the results. First, multicollinearity was assessed using the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) for all independent variables. As shown in Table 3, all VIF values were well below the conventional threshold of 10, ranging from 1.10 to 1.60 and thus indicating no significant collinearity among the explanatory variables. Second, the Wooldridge test for autocorrelation in panel data was performed to detect potential serial correlation in the residuals. The null hypothesis of no first-order autocorrelation could not be rejected (p > 0.10), which supported the assumption of error independence across time. To address potential heteroskedasticity, the model employed heteroskedasticity-robust standard errors clustered at the firm level, a standard technique in panel data econometrics to correct for within-group error correlation. Finally, the choice between a fixed-effects and random-effects model was resolved using the Hausman test, which strongly favored the fixed-effects specification (p < 0.05) and confirmed that unobserved firm-level characteristics were correlated with the regressors. Together, these preliminary tests validate the statistical soundness of Model 1 and support the use of fixed-effects estimation in analyzing the financial impact of ESG performance on Saudi insurance firms.

Table 3.

Variance Inflation Factor (VIF)—multicollinearity diagnostics for Model 1.

4. Empirical Results and Discussion

Table 4 provides the descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation, minimum, and maximum).

Table 4.

Descriptive statistics.

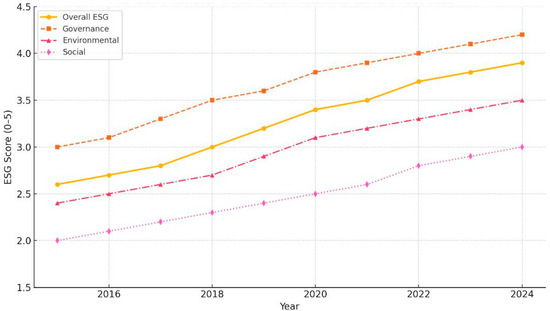

Figure 1 shows the ESG composite score and its three pillar trends (environmental, social, governance) from 2015 to 2024 based on synthesized data and is structured as follows. The analysis in Figure 1 reveals a steady improvement in ESG scores across Saudi insurers from 2015 to 2024, with the average composite score rising from 2.6 to 3.9 (on a 5-point scale). When we disaggregated the ESG pillars, governance exhibited the strongest performance, which was largely attributed to regulatory pressure from the Saudi Central Bank (SAMA) and alignment with Vision 2030 corporate governance mandates. The environmental scores rose notably, particularly after 2021 when structured ESG disclosure guidelines were introduced. Social performance, however, remained the weakest pillar, reflecting slower progress in diversity, financial inclusion, and community engagement programs.

Figure 1.

Trends by Pillar-Saudi insurance sector (2015–2024).

These trends align with international findings where governance metrics often lead ESG implementation due to clearer compliance mandates and board accountability [15,25]. Similar dynamics are seen in other emerging markets, where environmental and social indicators lag due to limited institutional infrastructure and lower public pressure [26].

The environmental performance, while improving from 2.4 to 3.5, remains constrained by a lack of industry-specific guidelines on climate-related disclosures. However, the issuance of the ESG Reporting Guidelines in 2021 marked a critical inflection point, catalyzing improvements in carbon reporting, green underwriting, and sustainable investment disclosure [8]. Yet, compared to sectors like energy or manufacturing, the insurance industry faces inherent challenges in quantifying and mitigating environmental impacts due to the lack of sector-wide risk models tailored to the Arabian Peninsula’s climate vulnerabilities (e.g., extreme heat, floods, dust storms).

Social metrics remain the weakest component, improving only modestly from 2.0 to 3.0. Several factors contribute to this lag. First, voluntary disclosures on gender diversity, employee welfare, and community engagement remain low, especially among smaller insurers [5]. Second, there is limited integration of financial inclusion metrics within mainstream insurance products, despite the push toward universal health coverage and microinsurance under Vision 2030 [27]. The social pillar’s slower progression reflects structural inertia and a lack of consumer-facing ESG incentives in the market.

This unbalanced ESG progression mirrors findings from global studies, which suggest that governance often precedes environmental and social dimensions in emerging markets due to clearer regulatory codification and fewer data challenges [15,26]. In the Saudi context, the absence of mandatory ESG audits, fragmented oversight, and limited ESG literacy across the insurance workforce further contribute to these disparities [3].

Nevertheless, the observed trajectory, particularly the post-2020 acceleration in governance and environmental scores, signifies the beginning of a structural transition in the insurance sector. As regulators strengthen ESG mandates and institutional investors like the Public Investment Fund (PIF) increasingly favor sustainability-aligned portfolios, ESG performance is likely to become a core metric of insurer credibility and competitiveness [28].

Table 5 presents the fixed-effects regression estimates that were used to assess the impact of ESG performance on return on assets (ROA).

Table 5.

Fixed-effects regression results.

The results show that a 1-point increase in ESG score is associated with a 0.36 percentage point increase in ROA, which is statistically significant at the 5% level. This finding supports the hypothesis that sustainability practices are financially material and can enhance profitability, which is consistent with meta-analytic evidence from over 2000 studies [25] and the stakeholder-value theory [29].

Firm size also shows a positive and significant association with profitability, reflecting economies of scale in ESG adoption. Company age showed no significant effect on ROA, indicating that ESG benefits accrue across firms regardless of their maturity. In the Saudi context, the positive and significant coefficient for YEAR indicates that, after controlling for firm-specific factors, there has been a systematic improvement in ROA across the sector, which is consistent with the rollout of Vision 2030 initiatives that target financial modernization, regulatory tightening by SAMA post-2016, and the increasing pressure for ESG disclosures, especially after 2021.

4.1. ESG and Risk Mitigation: Sensitivity Analyses

This model assesses whether firms with higher ESG scores experience lower underwriting risk, as captured by the loss ratio (claims incurred/premiums earned). A lower loss ratio typically indicates better risk assessment, better claims control, or more risk-conscious customer segments. The model tests the risk mitigation hypothesis in the ESG-finance literature, which is particularly relevant in the insurance sector.

Model specification: loss ratio as dependent variable

where:

- LR: Loss ratio = claims incurred/premiums earned;

- ESG: ESG composite score (0–5 scale);

- SIZE: natural log of total assets;

- AGE: years since license issuance;

- YEAR: linear time trend (2015 = 1 to 2024 = 10);

- μᵢ: firm fixed effects;

- εᵢₜ: error term.

Sensitivity analyses using the loss ratio (claims/premiums) as an alternative dependent variable reveal an inverse relationship with ESG scores, suggesting improved underwriting performance among sustainable insurers. The correlation remained robust after controlling for the firm size, age, and product type. This is consistent with the global literature indicating that ESG practices reduce exposure to non-diversifiable risks and improve operational resilience [30,31].

These findings underscore the dual benefit of ESG practices: enhancing profitability while reducing risk exposure. This is a particularly important insight for insurers who are both financial and risk intermediaries. The findings from Table 6 reveal a statistically significant negative association between ESG performance and the loss ratio (coefficient = −0.220, p = 0.030), indicating that insurers with stronger ESG scores tend to experience fewer claims relative to their premium income. This suggests that the adoption of ESG practices not only contributes to reputational value but also enhances underwriting efficiency and risk management capabilities. Notably, the firm size also shows a significant negative relationship with the loss ratio (p = 0.050), which reinforces the notion that larger insurers benefit from more robust actuarial systems and diversified risk pools. These results are consistent with Table 5, where the ESG score was positively associated with the return on assets (ROA) (β = 0.360, p = 0.020), which demonstrates that ESG-aligned insurers achieve superior financial performance.

Table 6.

Fixed-effects regression results (dependent variable: loss ratio).

Larger firms typically have greater access to ESG resources, more diversified risk pools, and better governance infrastructure, which may allow for more effective ESG practice implementation and monitoring. This translates into higher operational efficiency and profitability, a pattern supported in the ESG-finance literature [13,25].

Taken together, these two models confirm that ESG practice integration delivers a dual benefit: it boosts profitability while simultaneously mitigating operational risk. The consistent significance of the ESG coefficient across both ROA and loss ratio models underscores its material financial impact in the Saudi insurance context. This pattern supports the growing body of international literature that suggests that sustainability-oriented firms are more resilient and efficient in managing economic and environmental volatility [30,31]. In Saudi Arabia, where insurers face mounting climate risks and evolving regulatory standards under Vision 2030, the adoption of ESG practices appears to play a crucial role in differentiating high-performing firms. The evidence implies that ESG practices are not merely a compliance exercise, but a strategic lever for risk reduction and value creation in the insurance sector.

4.2. Qualitative Insights: Stakeholder Perceptions

The qualitative component of this study followed Braun and Clarke’s [10] six-phase thematic analysis approach to ensure systematic and reliable insight generation. A total of 18 semi-structured interviews were conducted with executives including CEOs, Chief Risk Officers, ESG leads, and regulatory officials from the Saudi Central Bank (SAMA) using purposive sampling to capture variation across firm sizes, insurance models (Takaful vs. conventional), and levels of ESG maturity. Additionally, three consumer focus groups (n = 24) were held in Riyadh and Jeddah to reflect public perspectives. All interviews and focus groups were recorded, transcribed verbatim, and anonymized. The transcripts were analyzed using NVivo 12 software. Initial codes were developed based on the Principles for Sustainable Insurance [4] and refined inductively. Two researchers independently coded all transcripts, and discrepancies were resolved through consensus to ensure intercoder reliability. Emergent themes were reviewed iteratively and aligned with key concepts from institutional theory and stakeholder theory. The resulting five themes, which included regulatory ambiguity, Vision 2030 alignment, and ESG capacity gaps, were supported by direct quotations and triangulated with findings from the quantitative analysis to enhance their interpretive validity.

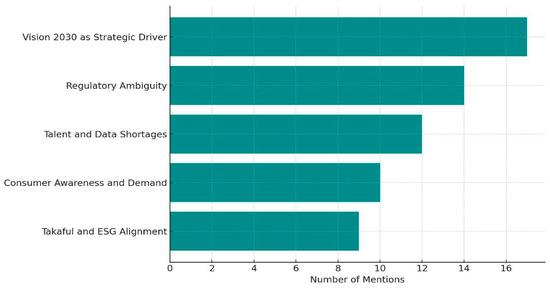

The coding of transcripts using NVivo software followed Braun and Clarke’s [10] six-phase thematic analysis, which resulted in the five dominant themes illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Key themes from interviews and focus groups.

- -

- Vision 2030 as strategic driver (17 mentions):

This theme was the most frequently cited, reflecting the centrality of Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 in shaping ESG priorities across the insurance sector. Participants emphasized that many ESG initiatives such as improved governance, inclusive insurance, and green underwriting are not organically market-driven but rather top-down mandates aligned with national policy. Firms view alignment with Vision 2030 as both a compliance necessity and a strategic opportunity for reputation and investor access.

“We are implementing ESG because Vision 2030 demands it, not because our clients are asking for it,” noted one CEO of a listed insurer.

This highlights the state-led nature of ESG diffusion in Saudi Arabia, which is consistent with the broader governance style in Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries [32].

- -

- Regulatory Ambiguity (14 mentions):

Stakeholders expressed concern over the lack of sector-specific ESG benchmarks and inconsistencies in reporting expectations. While SAMA and the Capital Market Authority have issued guidelines, these are often viewed as non-prescriptive or overlapping, which creates confusion in their implementation.

One CRO commented, “We are still guessing what counts as sufficient ESG disclosure. There is no checklist or verification system.”

This ambiguity risks turning ESG practices into a check-the-box exercise rather than a substantive transformation tool, which echoes findings in emerging markets where institutional clarity is limited [15].

- -

- Talent and Data Shortages (12 mentions):

A critical constraint identified was the shortage of ESG-literate professionals, including actuaries who are familiar with climate risks, sustainability auditors, and impact analysts. In addition, most firms lack reliable ESG performance data systems, which hampers score calculation and benchmarking.

This gap underlines the need for capacity-building and certification programs potentially integrated into licensing or Takaful board requirements if ESG practices are to be embedded at scale.

- -

- Consumer Awareness and Demand (10 mentions)

While interest in ESG-compliant products is growing, especially among digitally engaged youth, the overall consumer awareness remains low. Most participants in focus groups were unfamiliar with the concept of green or ethical insurance, and several associated it with higher costs.

A female participant in the Jeddah group noted, “I care about sustainability, but I don’t know if my insurance company offers anything green or different.”

This reflects a mismatch between insurer efforts and consumer literacy, indicating a need for targeted public education and marketing on ESG product benefits.

- -

- Takaful and ESG Alignment (9 mentions)

Executives from Islamic insurers viewed Takaful models as naturally aligned with ESG principles due to their ethical foundations in mutuality, transparency, and social solidarity. However, most agreed that this alignment remains underleveraged.

“We have an opportunity to position Takaful as a sustainability-first product,” one executive stated, “but we need to modernize how we present it.”

This suggests that Sharia-based insurance could act as a local bridge to global ESG standards, that modernization and disclosure reform are required for this to occur.

4.3. Discussion

This study employed a sequential explanatory mixed-methods design, in which the quantitative analysis was conducted first, followed by a qualitative phase designed to interpret and contextualize the statistical findings. The quantitative component used fixed-effects panel regression models to test the relationship between ESG performance and key financial indicators (return on assets and loss ratio) across 20 Saudi insurance firms over a 10-year period. This was complemented by a qualitative phase that involved 18 semi-structured interviews with executives and regulators and three consumer focus groups that were analyzed thematically using NVivo software and Braun and Clarke’s (2006) [10] six-step coding method. The integration of both methods enabled a multi-layered understanding of ESG dynamics. For example, while the quantitative results demonstrated that higher ESG scores are significantly associated with improved profitability and lower underwriting risk, the qualitative findings clarified that these improvements are largely driven by top-down policy reforms (Vision 2030), regulatory compliance pressure from SAMA [8], and capacity-building gaps within firms. This methodological synergy strengthens both the internal validity (by providing convergent evidence) and explanatory power of our findings, offering insights not just into what ESG-performance patterns exist, but also why they occur and how they are institutionally mediated in an emerging market setting. This integrated approach makes this study particularly relevant for policymakers and scholars interested in ESG adoption beyond Western, market-driven contexts.

The integrated analysis of quantitative and qualitative data provides a nuanced understanding of ESG dynamics within Saudi Arabia’s insurance sector. The positive association between ESG performance and profitability measured through the return on assets metric echoes findings from global meta-analyses [25,26] and reinforces the growing consensus that strong ESG practices contribute to better financial outcomes. This relationship is particularly salient in emerging markets like Saudi Arabia, where ESG investments often yield disproportionate reputational and operational benefits due to the relative novelty and signaling value of such commitments [11].

Governance improvements have been the most visible outcome, being supported by regulatory interventions and Vision 2030 imperatives. These include board reforms, risk oversight enhancements, and better disclosure practices, which aligns with global frameworks such as GRI and SASB. However, the social and environmental pillars have progressed more modestly. The slow uptake in social sustainability practices such as inclusive insurance, gender diversity, and community engagement reflects institutional inertia, limited consumer awareness, and underdeveloped distribution channels [19,22].

Qualitative findings further validate these observations. Executives widely cited Vision 2030 as a guiding force behind sustainability efforts, but lamented the lack of sector-specific ESG benchmarks and consistent regulatory expectations. Participants highlighted a pressing need for ESG capacity-building, including actuarial training, data systems, and third-party assurance mechanisms. The intersection of ESG and Islamic finance emerged as a distinctive local strength. Takaful models, being inherently based on mutuality and ethical principles, were seen as naturally aligned with ESG priorities, which suggests that Sharia-compliant products could act as a bridge between traditional values and contemporary sustainability frameworks [7].

Overall, this study affirms that sustainability and profitability are not mutually exclusive but are mutually reinforcing when embedded within a coherent strategic framework. Saudi insurers stand to benefit from deeper ESG integration not only through financial gains but also by contributing to systemic resilience, regulatory compliance, and reputational capital. To fully realize this potential, policy and industry leaders must address the foundational enablers: consistent regulations, reliable ESG data, inclusive innovation, and professional training. Only then can the sector transition from compliance-oriented ESG practices to a genuinely transformative sustainability model.

These findings reinforce the argument that the adoption of ESG principles in Saudi Arabia is neither wholly market-driven nor purely compliance-based. Rather, it emerges from a unique convergence of state-led transformation, evolving regulatory mandates, and developmental imperatives under Vision 2030.

These outcomes mirror trends in other MENA markets, such as the UAE and Egypt, where ESG adoption is often compliance-driven and uneven across ESG pillars [32]. By situating the Saudi case within the broader context of regional institutional reform, this study affirms that ESG practices in emerging markets are best understood through an institutional theory lens, where state-led legitimacy pressures outweigh market incentives. Moreover, the observed financial benefits of the adoption of ESG principles underscore the resource-based view, wherein ESG capabilities constitute valuable intangible assets that enhance firms’ competitiveness.

This hybrid governance model distinguishes Saudi Arabia from both typical developed and emerging market ESG trajectories and offers a valuable empirical case for understanding how ESG practices can operate as a strategic lever in non-Western institutional contexts. This study therefore contributes not only to ESG scholarship but also to broader debates on governance innovation, sustainable finance, and institutional transitions in emerging economies.

5. Conclusions and Implications

The literature reveals that the integration of ESG practices in Saudi Arabia’s insurance sector is progressing but remains at varying stages of development. While governance aspects have received significant attention, environmental and social dimensions require further development. Vision 2030 serves as a key driver for reform, with Takaful and sustainable product innovation offering promising opportunities for future growth. However, the successful implementation of this reform depends on addressing current challenges in regulatory oversight, standardization, and capacity building.

Building on the empirical findings and stakeholder insights of this study, we conclude that the integration of ESG principles into insurance operations in Saudi Arabia is both financially advantageous and socially essential. The evidence shows that insurers who invest in structured, transparent ESG practices experience tangible benefits, including improved profitability and reduced underwriting risk. Governance practices, underpinned by Vision 2030 mandates and regulatory pressure from the Saudi Central Bank, have matured significantly. The environmental and social dimensions, however, continue to lag, which suggests the need for a more balanced and comprehensive approach. These findings carry several important implications. Policymakers must prioritize ESG policy standardization across the insurance sector, and should potentially transition from voluntary disclosure regimes to mandatory frameworks that are aligned with international benchmarks such as the TCFD and GRI. Regulators can further support the adoption of ESG practices by offering incentives for sustainable insurance products, establishing green premium subsidies, and encouraging public–private partnerships that address community resilience and climate risk. From a managerial standpoint, insurance firms should strengthen ESG governance at the board level, invest in ESG analytics and disclosure infrastructure, and incorporate sustainability metrics into product design and customer engagement. Moreover, capacity-building initiatives, including training for actuaries, risk managers, and underwriters, are critical for embedding ESG values into core insurance functions. On a societal level, the enhanced integration of ESG practices in the insurance sector can support Saudi Arabia’s climate commitments, reduce systemic financial vulnerabilities, and promote financial inclusion, particularly through microinsurance and Takaful products. By viewing sustainability as an opportunity rather than a compliance obligation, insurers in Saudi Arabia can play a pivotal role in shaping a resilient and inclusive financial ecosystem that aligns with national development goals.

Limitations and Future Research

While this study offers new empirical insights into the integration of ESG principles in Saudi Arabia’s insurance sector, it is subject to certain limitations that future research could address. First, the dataset relies primarily on publicly disclosed ESG data, which may be inconsistent or incomplete, particularly for the earlier years in the panel. Second, the fixed-effects regression model, while effective in capturing firm-level variation over time, does not fully address potential endogeneity or unobserved heterogeneity in strategic ESG practice adoption. Future studies could use instrumental variable approaches or natural experiments to strengthen the causal inference of their approach. Third, the qualitative component, while rich in insight, is based on a sample of 18 interviews and three focus groups, which may not be fully representative of the entire market. Expanding the qualitative sample or employing large-scale surveys could enhance the generalizability of the chosen approach. Additionally, this research focused exclusively on the Saudi context; comparative studies across GCC countries or broader MENA markets would offer valuable regional benchmarks. Furthermore, the sample selection being restricted to 20 out of 28 licensed insurers with consistent ESG reporting between 2015 and 2024 introduces the potential for survivorship and selection bias. Firms with sustained ESG disclosures are more likely to be larger, financially stable, and better aligned with regulatory expectations such as Vision 2030. Consequently, the analysis may overstate the strength or generalizability of the ESG practices–performance relationship by excluding firms with limited disclosure capacity, that are in financial distress, or which are non-compliant. While this approach ensures longitudinal validity and data reliability, it has limited external validity and may bias the findings toward stronger ESG performers. Future research could address this limitation by using imputation techniques, broadening the sample to include partially reporting firms, or applying Heckman correction models to control for selection effects.

Finally, future research could explore consumers’ demand and willingness to pay for green or inclusive insurance products, which would shed light on the market viability of ESG innovations and inform product development strategies.

Funding

This research was supported and funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research of Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University (IMSIU), (grant number IMSIU-DDRSP2502).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to current local research governance frameworks in Saudi Arabia. This practice is based on the official guidelines issued by the National Committee of Bioethics (NCBE), under Royal Decree No. M/59 dated 14/09/1431H, and further elaborated in the "Law of Ethics of Research on Living Creatures". The NCBE’s regulations outline that: “Exempt reviews are conducted by the Chair or an assigned IRB member, and such projects do not require a full committee meeting or the issuance of a formal exemption certificate.” You can consult the full NCBE regulatory document at the following official link: https://irb.alfaisal.edu/wp-content/uploads/pdf/NCBE-Guidelines.pdf, accessed on 1 June 2025.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the author on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Boufounou, P.; Tinos, D. Stock Markets Integration Perspectives Towards Sustainable Finance: Evidence of Developed and Emerging Financial Markets; Reference Module in Social Sciences; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodaed Alsheikh, A.; Hodaed Alsheikh, W. The level of climate risk reporting performance and firm characteristics: Evidence from the Saudi Stock Exchange. Invest. Manag. Financ. Innov. 2023, 20, 360–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L. Environmental performance factors: Insights from CSR-linked compensation, committees, disclosure, targets, and board composition. J. Sustain. Financ. Invest. 2024, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Environment Programme Finance Initiative (UNEP FI). Principles for Sustainable Insurance (PSI). 2022. Available online: https://www.unepfi.org/psi/ (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Azid, T.; Alnodel, A.A. Determinants of Shari’ah governance disclosure in financial institutions. Int. J. Ethic-Syst. 2018, 35, 207–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelili Amuda, Y.; Alabdulrahman, S. Reinforcing policy and legal framework for Islamic insurance in Islamic finance: Towards achieving Saudi Arabia Vision 2030. Int. J. Law Manag. 2023, 65, 600–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, K. Managing risk by Takaful Malaysia. In Islamic Management Practices in Financial Institutions; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; pp. 92–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saudi Central Bank (SAMA). Guidelines on ESG Reporting for Financial Institutions. 2024. Available online: https://rulebook.sama.gov.sa/en/d4-focus-environmental-social-and-governance-esg (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- OECD. ESG and Sustainability in Finance; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2023; Available online: https://www.oecd.org/finance/esg-and-sustainability.htm (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amel-Zadeh, A.; Serafeim, G. Why and how investors use ESG information: Evidence from a global survey. Financ. Anal. J. 2018, 74, 87–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apicella, G.; Carannante, M.; D’aMato, V. Policyholders’ subjective beliefs: Approaching new drivers of insurance ESG reputational risk. Decis. Econ. Financ. 2025, 47, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maama, H. Achieving financial sustainability in Ghana’s banking sector: Is environmental, social and governance reporting contributive? Glob. Bus. Rev. 2021, 2, 09721509211044300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boffo, R.; Patalano, R. ESG Investing: Practices, Progress and Challenges; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Singhania, M.; Saini, N. Institutional framework of ESG disclosures: Comparative analysis of developed and developing countries. J. Sustain. Financ. Invest. 2023, 13, 516–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Kim, K.; Ivantsova, A. Insights from the mandatory insurer climate risk disclosure survey in the United States. Risk Manag. Insur. Rev. 2023, 26, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. World Development Report 2022: Finance for an Equitable Recovery; World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churchill, C.; Matul, M. (Eds.) Protecting the Poor: A Microinsurance Compendium; International Labour Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Giráldez-Puig, P.; Moreno, I.; Perez-Calero, L.; Guerrero Villegas, J. ESG controversies and insolvency risk: Evidence from the insurance industry. Manag. Decis. 2025, 63, 610–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, P.J.; Powell, W.W. The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1983, 48, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, A.E.; Baalbaki Shibly, F.; Haddad, R. Voluntary disclosure of accounting ratios and firm-specific characteristics: The case of GCC. J. Financ. Rep. Account. 2020, 18, 301–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Plano Clark, V.L. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wooldridge, J.M. Econometric Analysis of Cross Section and Panel Data, 2nd ed.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Friede, G.; Busch, T.; Bassen, A. ESG and financial performance: Aggregated evidence from more than 2000 empirical studies. J. Sustain. Financ. Invest. 2015, 5, 210–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfonso-Ercan, C. Private equity and ESG investing. In Values at Work; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, M. Islamic finance, benchmarking, and the LIBOR transition. In Benchmarking Islamic Finance; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; pp. 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, S.; Rohleder, M.; Wilkens, M.; Zink, J. The Effects of ESG Investing on (Un)Sustainable Stock Returns: Distinguishing Static and Dynamic ESG Allocation. SSRN 2024. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=5131089 (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Eccles, R.G.; Ioannou, I.; Serafeim, G. The impact of corporate sustainability on organizational processes and performance. Manag. Sci. 2014, 60, 2835–2857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krüger, P. Corporate goodness and shareholder wealth. J. Financ. Econ. 2015, 115, 304–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chebbi, K.; Ammer, M.A. Board composition and ESG disclosure in Saudi Arabia: The moderating role of corporate governance reforms. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).