Investigating the Impact of Social Marketing on Tourists’ Behavior for Attaining Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Consumer Behavior in Tourism for Attaining SDG11&12

2.2. The Applications of Social Marketing in Tourism

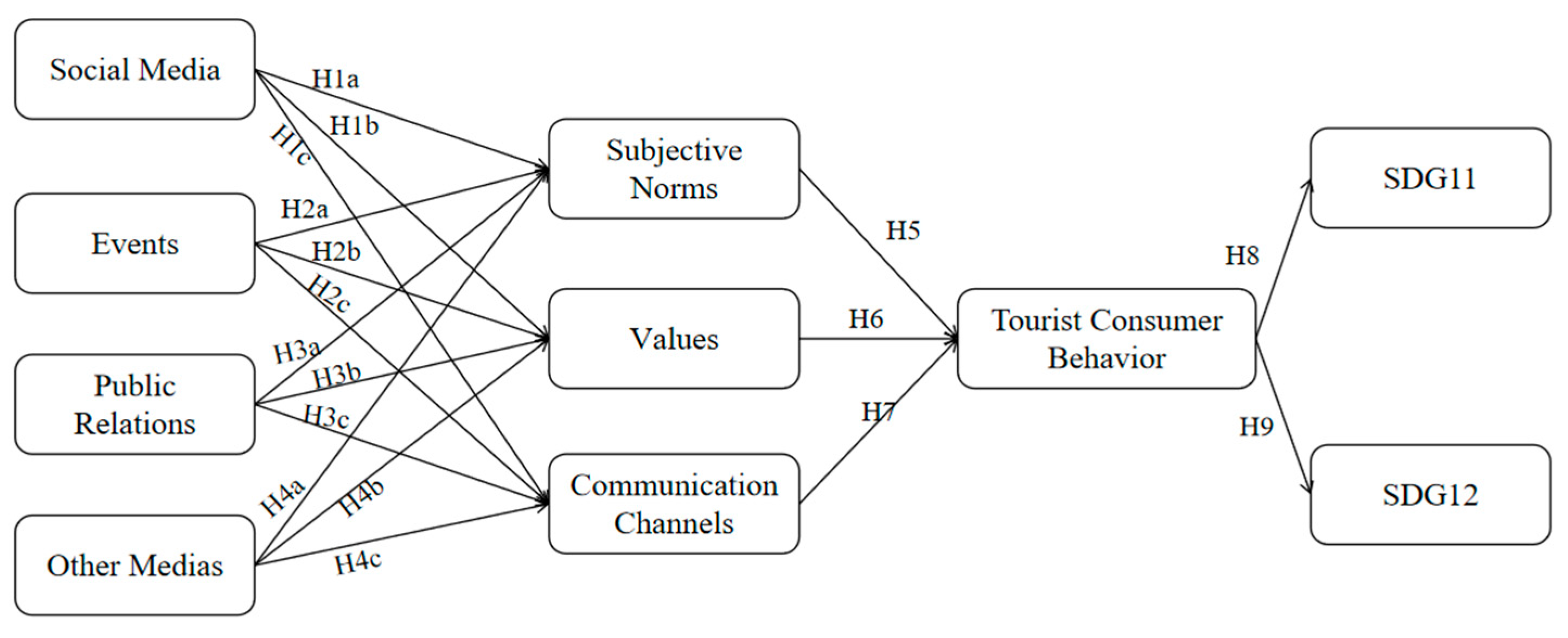

3. Theoretical Framework, Hypotheses Development, and Conceptual Model

3.1. The Means/Media of Social Marketing and Their Effect

3.1.1. The Influence of Social Media on Subjective Norms, Values, and Communication Channels

3.1.2. The Influence of Events on Subjective Norms, Values, and Communication Channels

3.1.3. The Influence of Public Relations on Subjective Norms, Values, and Communication Channels

3.1.4. Other Media

3.2. The Effect of Influencing/Mediating Factors on Consumer Behavior

3.2.1. Subjective Norms

3.2.2. Values

3.2.3. Communication Channels

4. Method

4.1. Questionnaire Design

4.2. The Sample and Data Collection

5. Results

5.1. Reliability and Validity Test of the Questionnaire

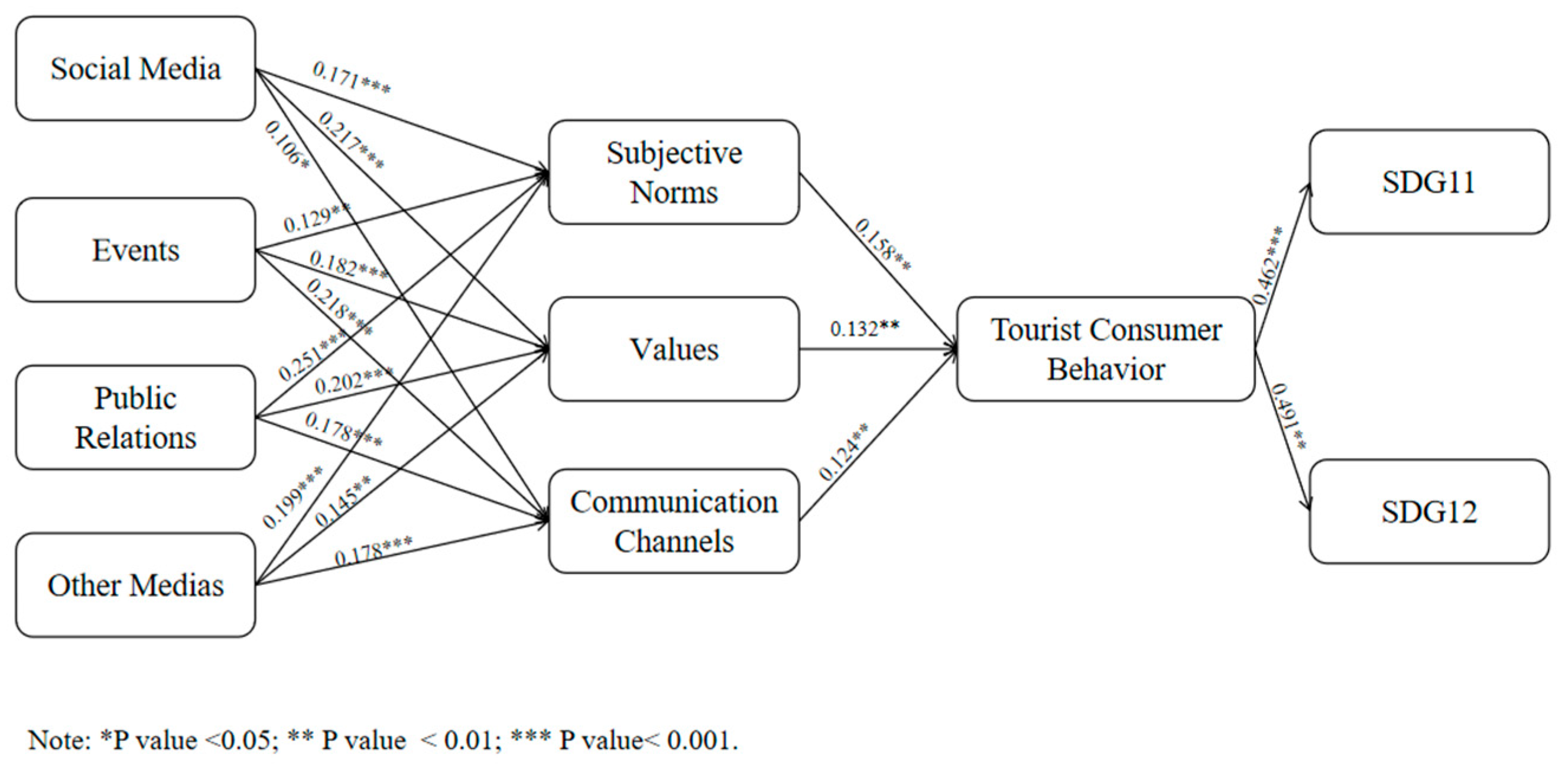

5.2. Structural Model Evaluation

5.3. Mediating Effect Analysis

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions and Implications

7.1. Theoretical Implication

7.2. Practical Implications

7.3. Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UNWTO. World Tourism Organization: Global Carbon Emissions from Tourism and Transportation Will Reach 1.998 Billion Tons in 2030. Available online: https://news.un.org/en/content/navigate-news (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- UNWTO. World Tourism Organization: World Tourism Barometer. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/un-tourism-world-tourism-barometer-data (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Goniewicz, K.; Khorram-Manesh, A.; Burkle, F.M. Beyond Boundaries: Addressing Climate Change, Violence, and Public Health. Prehospital Disaster Med. 2023, 38, 551–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Ali, A.; Chen, Y.; She, X. The Effect of Transport Infrastructure (Road, Rail, and Air) Investments on Economic Growth and Environmental Pollution and Testing the Validity of EKC in China, India, Japan, and Russia. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 30, 32585–32599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sangroya, D.; Nayak, J.K. Factors Influencing Buying Behaviour of Green Energy Consumer. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 151, 393–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, J.; Basil, D.Z.; Wymer, W. Using Social Marketing to Enhance Hotel Reuse Programs. J. Bus. Res. 2010, 63, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheau-Ting, L.; Mohammed, A.H.; Weng-Wai, C. What Is the Optimum Social Marketing Mix to Market Energy Conservation Behaviour: An Empirical Study. J. Environ. Manag. 2013, 131, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh, P.R.; Dodds, R. The Impact of Intermediaries and Social Marketing on Promoting Sustainable Behaviour in Leisure Travellers. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 338, 130537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory-Smith, D.; Wells, V.K.; Manika, D.; McElroy, D.J. An Environmental Social Marketing Intervention in Cultural Heritage Tourism: A Realist Evaluation. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 25, 1042–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkaczynski, A.; Rundle-Thiele, S.; Truong, V.D. Influencing Tourists’ Pro-Environmental Behaviours: A Social Marketing Application. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 36, 100740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peattie, K.; Peattie, S. Social Marketing: A Pathway to Consumption Reduction? J. Bus. Res. 2009, 62, 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunkoo, R.; Sharma, A.; Rana, N.P.; Dwivedi, Y.K.; Sunnassee, V.A. Advancing Sustainable Development Goals through Interdisciplinarity in Sustainable Tourism Research. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 31, 735–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boluk, K.A.; Cavaliere, C.T.; Higgins-Desbiolles, F. A Critical Framework for Interrogating the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals 2030 Agenda in Tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 847–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakari, A.; Li, G.; Khan, I.; Jindal, A.; Tawiah, V.; Alvarado, R. Are Abundant Energy Resources and Chinese Business a Solution to Environmental Prosperity in Africa? Energy Policy 2022, 163, 112829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.-Y.; Li, H.; Chen, X.-Z.; Yu, L. Can Tax Incentives Foresee the Restructuring Performance of Tourism Firms?—An Event-Driven Forecasting Study. Tour. Manag. 2024, 102, 104882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Tonder, E.; Fullerton, S.; De Beer, L.T.; Saunders, S.G. Social and Personal Factors Influencing Green Customer Citizenship Behaviours: The Role of Subjective Norm, Internal Values and Attitudes. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 71, 103190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Q.; Umer, Q.; Zhou, R.; Asmi, A.; Asmi, F. How Publications and Patents Are Contributing to the Development of Municipal Solid Waste Management: Viewing the UN Sustainable Development Goals as Ground Zero. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 325, 116496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, V.; Silva, G.M.; Dias, Á. Sustainability Practices in Hospitality: Case Study of a Luxury Hotel in Arrábida Natural Park. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leknoi, U.; Yiengthaisong, A.; Likitlersuang, S. Social Factors Influencing Waste Separation Behaviour among the Multi-Class Residents in a Megacity: A Survey Analysis from a Community in Bangkok, Thailand. Sustain. Futures 2024, 7, 100202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhler, J.; Whitmarsh, L.; Nykvist, B.; Schilperoord, M.; Bergman, N.; Haxeltine, A. A transitions model for sustainable mobility. Ecol. Econ. 2009, 68, 2985–2995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, Á.; Aldana, I.; Pereira, L.; da Costa, R.L.; António, N. A Measure of Tourist Responsibility. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halder, P.; Hansen, E.N.; Kangas, J.; Laukkanen, T. How National Culture and Ethics Matter in Consumers’ Green Consumption Values. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 265, 121754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogiemwonyi, O.; Jan, M.T. The Correlative Influence of Consumer Ethical Beliefs, Environmental Ethics, and Moral Obligation on Green Consumption Behavior. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. Adv. 2023, 19, 200171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Liu, S.; Li, H.; Yang, Z.; Liang, S.; Deng, N. Love of Nature as a Mediator between Connectedness to Nature and Sustainable Consumption Behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 242, 118451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H. Consumer Behavior and Environmental Sustainability in Tourism and Hospitality: A Review of Theories, Concepts, and Latest Research. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 29, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, N.; Kotler, P. Social Marketing: Influencing Behaviors for Good; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kotler, P.; Lee, N. Social Marketing: Changing Behaviors for Good, 5th ed.; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Truong, V.D.; Hall, C.M. Corporate Social Marketing in Tourism: To Sleep or Not to Sleep with the Enemy? J. Sustain. Tour. 2016, 25, 884–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, V.D. Social Marketing: A Systematic Review of Research 1998–2012. Soc. Mark. Q. 2014, 20, 15–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, M. Social Marketing for Social Change. Soc. Mark. Q. 2016, 22, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borden, D.S.; Coles, T.; Shaw, G. Social Marketing, Sustainable Tourism, and Small/Medium Size Tourism Enterprises: Challenges and Opportunities for Changing Guest Behaviour. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 25, 903–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagle, L.; Hay, R.; Farr, M. Harnessing the Science of Social Marketing and Behaviour Change for Improved Water Quality in the GBR: Background Review of the Literature; Reef and Rainforest Research Centre Limited: Cairns, QLD, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hanafizadeh, P.; Shafia, S.; Bohlin, E. Exploring the Consequence of Social Media Usage on Firm Performance. Digit. Bus. 2021, 1, 100013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, J.; Blair-Stevens, C. Social Marketing Pocket Guide; National Social Marketing Centre: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasbullah, N.A.; Osman, A.; Abdullah, S.; Salahuddin, S.N.; Ramlee, N.F.; Soha, H.M. The Relationship of Attitude, Subjective Norm and Website Usability on Consumer Intention to Purchase Online: An Evidence of Malaysian Youth. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2016, 35, 493–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S. An Overview of the Schwartz Theory of Basic Values. Psychol. Cult. Artic. 2012, 2, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabioun, M. A Multi-Theoretical View on Social Media Continuance Intention: Combining Theory of Planned Behavior, Expectation-Confirmation Model and Consumption Values. Digit. Bus. 2024, 4, 100070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreasen, A.R. Attitude and Consumer Behavior: A Decision Model in New Research; Institute of Business and Economic Research, University of California: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1965; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, X.T. Sociological Research Methods; Renmin University of China Press: Beijing, China, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Fleisher, L.; Wen, K.Y.; Miller, S.M.; Diefenbach, M.; Stanton, A.L.; Ropka, M.; Morra, M.; Raich, P.C. Development and Utilization of Complementary Communication Channels for Treatment Decision Making and Survivorship Issues among Cancer Patients: The CIS Research Consortium Experience. Internet Interv. 2015, 2, 392–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suk, M.; Kim, M.; Kim, W. The Moderating Role of Subjective Norms and Self-Congruence in Customer Purchase Intentions in the LCC Market: Do Not Tell Me I Am Cheap. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2020, 41, 100595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgeson, F.P. The External Leadership of Self-Managing Teams: Intervening in the Context of Novel and Disruptive Events. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 497–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Organ, K.; Koenig-Lewis, N.; Palmer, A.; Probert, J. Festivals as agents for behaviour change: A study of food festival engagement and subsequent food choices. Tour. Manag. 2015, 48, 84–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyeiwaah, E.; Zhao, Y. Residents’ Perceived Social Sustainability of Food Tourism Events. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2024, 53, 101276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, F.; Liu, M. Sociology of Events: From “Structure-Event” to “Relational-Event”. Sociol. Stud. 2024, 01, 204–225. [Google Scholar]

- McCaffrey, S. Community Wildfire Preparedness: A Global State-of-The-Knowledge Summary of Social Science Research. Curr. For. Rep. 2015, 1, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernays, E.L. Crystallizing Public Opinion; New Hall Press: Hoylake, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cutlip, S.M. The Unseen Power; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, A.; Rana, N.P.; Parayitam, S. Role of Social Currency in Customer Experience and Co-Creation Intention in Online Travel Agencies: Moderation of Attitude and Subjective Norms. Int. J. Inf. Manag. Data Insights 2022, 2, 100114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath, R.L.; Waymer, D. Public Relations Intersections: Statues, Monuments, and Narrative Continuity. Public Relat. Rev. 2019, 45, 101766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, J.E.; Preston, L.E.; Sauter-Sachs, S. Redefining the Corporation: Stakeholder Management and Organizational Wealth; California Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, D.K.; Hinson, M.D. Tracking How Social and Other Digital Media Are Being Used in Public Relations Practice: A Twelve-Year Study. Public Relat. J. 2017, 11, 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Gutuskey, L.; Wolford, B.K.; Wilkin, M.K.; Hofer, R.; Fantacone, J.M.; Scott, M.K. Healthy Choices Catch On: Data-Informed Evolution of a Social Marketing Campaign. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2022, 54, 818–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tandon, A.; Dhir, A.; Madan, P.; Srivastava, S.; Nicolau, J.L. Green and Non-Green Outcomes of Green Human Resource Management (GHRM) in the Tourism Context. Tour. Manag. 2023, 98, 104765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casaló, L.V.; Escario, J.-J. Heterogeneity in the Association between Environmental Attitudes and Pro-Environmental Behavior: A Multilevel Regression Approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 175, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garay, L.; Font, X.; Corrons, A. Sustainability-Oriented Innovation in Tourism: An Analysis Based on the Decomposed Theory of Planned Behavior. J. Travel Res. 2018, 58, 622–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, T.; Hsu, C.H.C. Predicting Behavioral Intention of Choosing a Travel Destination. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 589–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparks, B.; Pan, G.W. Chinese Outbound Tourists: Understanding Their Attitudes, Constraints and Use of Information Sources. Tour. Manag. 2009, 30, 483–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastings, G.; Domegan, C. Social Marketing: Rebels with a Cause; Routledge: Abingdon, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- French, J.; Gordon, R. Strategic Social Marketing; Sage Publications S.L.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Han, H.; Hyun, S.S. What Influences Water Conservation and Towel Reuse Practices of Hotel Guests? Tour. Manag. 2018, 64, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.; Peng, N. Antecedents to Consumers’ Green Hotel Stay Purchase Behavior during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Influence of Green Consumption Value, Emotional Ambivalence, and Consumers’ Perceptions. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2023, 47, 101107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiatkawsin, K.; Han, H. Young Travelers’ Intention to Behave Pro-Environmentally: Merging the Value-Belief-Norm Theory and the Expectancy Theory. Tour. Manag. 2017, 59, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dijk, G.; Minocha, S.; Laing, A. Consumers, Channels and Communication: Online and Offline Communication in Service Consumption. Interact. Comput. 2007, 19, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conrads, J.; Lotz, S. The Effect of Communication Channels on Dishonest Behavior. J. Behav. Exp. Econ. 2015, 58, 88–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Holtz, D.; Jaffe, S.; Suri, S.; Sinha, S.; Weston, J.; Joyce, C.; Shah, N.; Sherman, K.; Hecht, B.; et al. The Effects of Remote Work on Collaboration among Information Workers. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2021, 6, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, E.-J.; Oh, S.Y. To Personalize or Depersonalize? When and How Politicians’ Personalized Tweets Affect the Public’s Reactions. J. Commun. 2012, 62, 932–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sano, K.; Sano, H. The Effect of Different Crisis Communication Channels. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 79, 102804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armutcu, B.; Ramadani, V.; Zeqiri, J.; Dana, L.P. The Role of Social Media in Consumers’ Intentions to Buy Green Food: Evidence from Türkiye. Br. Food J. 2023, 126, 1923–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, C.; Shen, G.Q.; Choi, S. The Moderating Effect of Subjective Norm in Predicting Intention to Use Urban Green Spaces: A Study of Hong Kong. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 37, 288–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzidzornu, E.; Angmorterh, S.K.; Aboagye, S.; Angaag, N.A.; Agyemang, P.N.; Edwin, F. Communication Channels of Breast Cancer Screening Awareness Campaigns among Women Presenting for Mammography in Ghana. J. Am. Coll. Radiol. 2024, 21, 1201–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, Q.; Parveen, S.; Yaacob, H.; Zaini, Z.; Sarbini, N.A. COVID-19 and Dynamics of Environmental Awareness, Sustainable Consumption and Social Responsibility in Malaysia. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 56199–56218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, L.; Hsu, M.K.; Boostrom, R.E. From Recreation to Responsibility: Increasing Environmentally Responsible Behavior in Tourism. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 109, 557–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T.-M.; Wu, H.C. How Do Environmental Knowledge, Environmental Sensitivity, and Place Attachment Affect Environmentally Responsible Behavior? An Integrated Approach for Sustainable Island Tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2014, 23, 557–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Danks, N.P.; Ray, S. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using R: A Workbook; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Sarstedt, M.; Hair, J.F.; Pick, M.; Liengaard, B.D.; Radomir, L.; Ringle, C.M. Progress in Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling Use in Marketing Research in the Last Decade. Psychol. Mark. 2022, 39, 1035–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, C.; Kim, W.B.; Lee, S.H.; Baek, E.; Yan, X.; Yeon, J.; Yoo, Y.; Kang, S. Relations among Consumer Boycotts, Country Affinity, and Global Brands: The Moderating Effect of Subjective Norms. Asia Pac. Manag. Rev. 2024, 30, 100335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, P.; He, Y.; Xu, F. Evolutionary Analysis of Sustainable Tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2018, 69, 76–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Q.L.; Hashim, S.B.; Abdullah, N.L.; Zaki, H.O.; Zheng, Z. Bibliometric insights into the impact of values on consumer sustainable environmental behavior: Current trends and future directions. Sustain. Futures 2025, 9, 100582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, J.J.; Shore Ingber, A. Distinguishing Social Virtual Reality: Comparing Communication Channels across Perceived Social Affordances, Privacy, and Trust. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2024, 161, 108427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.; Osman, S.; Zainudin, N.; Yao, P. How Information and Communication Overload Affect Consumers’ Platform Switching Behavior in Social Commerce. Heliyon 2024, 10, e31603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agya, B.A. Technological Solutions and Consumer Behaviour in Mitigating Food Waste: A Global Assessment across Income Levels. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2025, 55, 242–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.S.; Tan, C.C.; Sinha, R.; Selem, K.M. Gaps between customer compatibility and usage intentions: The moderation function of subjective norms towards chatbot-powered hotel apps. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2024, 123, 103910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irfan, A.; Bryła, P. Green Marketing Strategies for Sustainable Food and Consumer Behavior: A Systematic Literature Review and Future Research Agenda. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 486, 144597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, P.F.; Wang, R.; Li, A.P.S.Y.; Qu, A.P.Z. Social Media Advertising through Private Messages and Public Feeds: A Congruency Effect between Communication Channels and Advertising Appeals. Inf. Manag. 2022, 59, 103646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalewski, K.; Lindemann, K.; Halaska, M.J.; Zapardiel, I.; Laky, R.; Chereau, E.; Lindquist, D.; Polterauer, S.; Sukhin, V.; Dursun, P. A Call for New Communication Channels for Gynecological Oncology Trainees. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2017, 27, 620–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Social Marketing Channels | Example |

|---|---|

| Social media | “Curators of Sweden”: The Swedish government assigns the management of the official Twitter account, @Sweden, to different citizens every week, allowing them to share their real-life experiences. This “rotation–curation” model has successfully shaped Sweden’s image as an open and inclusive country. Liberal arts public relations research shows that this “citizen diplomacy” strategy is more likely to gain the trust of international audiences than traditional state advocacy. |

| Events | The Coca-Cola “Share a Coke” event in Kenya involved replacing the logo on Coca-Cola bottles with names to create personalized souvenirs, encouraging everyone to stay in touch with friends and family, create lasting memories, and foster offline social interaction. The event emphasizes “authentic social experiences” to combat social distancing in the digital age. |

| Public Relations | “H&M Garment Recycling System”: H&M translates its environmental commitment into a tangible consumer experience by visualizing the recycling process of used clothes through a transparent window. This PR strategy not only enhances brand reputation but also drives the industry’s focus on the circular economy, demonstrating how “social marketing” can transform consumer behavior through transparent communication. |

| Other Medias | The Michigan Fitness Foundation piloted a new social marketing tagline (i.e., promoting healthy choices) and professionally designed messages and images. The campaign promotes healthy eating and increases public awareness through billboards, bus signs, and ground materials such as banners used by local enforcement agencies, A-frame signs, pop-up tables, and tablecloths. |

| Constructs | Measurement Items | Supporting Library Source |

|---|---|---|

| Social media | SM1: During my trips/holidays, the use of social media (WeChat, Weibo, Red Book, and TikTok) affects my purchase of green products. | Armutcu et al. [70] |

| SM2: The content on social media (WeChat, Weibo, Xiaohongshu, and TikTok) about green products and other sustainable consumption is trustworthy. | ||

| SM3: The content on social media (WeChat, Weibo, Xiaohongshu, and TikTok) regarding green products and sustainable consumption is generally reliable. | ||

| Events (EV) | EV1: During my trips/holidays, participating in or understanding various events and festivals affects my purchase of green products. | |

| EV2: The communication and content of sustainable consumption at various events and festivals are trustworthy. | ||

| EV3: The communication and content of sustainable consumption at various events and festivals are reliable. | ||

| Public Relations (PR) | PR1: During my trips and holidays, PR messages (statements, notices, presentations, and events) affect my purchase of green products. | |

| PR2: The communications and content about sustainable consumption through PR activities are trustworthy. | ||

| PR3: The communications and content about sustainable consumption through PR activities are reliable. | ||

| Other Medias (OM) | OM1: During my trips/holidays, the messages by other media (magazines, journals) affect my purchase of green products. | |

| OM2: The communications and content about sustainable consumption from other media (magazines, newspapers) are trustworthy. | ||

| OM3: The communications and content about sustainable consumption from other media (magazines and newspapers) are reliable. | ||

| Subjective Norms (SN) | SN1: Most people who are important to me support me in adopting green consumption behavior. | Wan et al. [71] |

| SN2: My friends think I should have green consumption behavior. | ||

| SN3: My family thinks that I should adopt green consumption behavior. | ||

| SN4: Colleagues and peers who work with me think that I should adopt sustainable consumption behavior. | ||

| Values (VA) | VA1: The value of “unite nature” has an impact on my consumption behavior. | Han et al. [62] |

| VA2: The value of “respect for the earth” has an impact on my consumption behavior. | ||

| VA3: The value of “pollution prevention” has an impact on my consumption behavior. | ||

| VA4: The value of “protecting and preserving the environment” has an impact on my consumption behavior. | ||

| Communication Channels (CC) | CC1: The mass media (TV, radio, magazines, and billboards) affect my consumption choices. | Dzidzornu et al. [72] |

| CC2: Communications with other people (peers, social groups, relatives, and friends) influence my consumption choices. | ||

| CC3: Communications by other entities (tourism companies, national tourism organizations, local tourism offices, and other bodies) affect my consumption choices. | ||

| Consumer Behavior (CB) | CB1: My consumption habits have become more environmentally friendly during my trips. | Ali et al. [73]; Su et al. [74] |

| CB2: When on holiday, I buy more environmentally friendly and green products. | ||

| CB3: During my trips, I have reduced waste production through prevention, reuse, and recycling. | ||

| CB4: I attempt to convince my travel companions to protect the natural environment of the visited place. | ||

| CB5: I like to participate in environmentally friendly activities | ||

| SDG11 | SDG11-1: I always opt for public transport. | Cheng & Wu [75] |

| SDG11-2: When visiting, I give priority to low-emission and sustainable modes of transport, such as bicycles. | ||

| SDG11-3: I handle waste properly, sorting and recycling. | ||

| SDG11-4: I avoid packaging and reduce the use of plastics. | ||

| SDG12 | SDG12-1: During my trips, I prefer reusable and recyclable products to minimize waste. | Borden et al. [31] |

| SDG12-2: During my trips, I order moderately and pack the remaining food to reduce food waste. | ||

| SDG12-3: During my trips, I save water (in the shower and kitchen). | ||

| SDG12-4: I save energy by properly using electric devices and equipment (e.g., air conditioning) during my trips. |

| Demographic Variable | N | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 258 | 45.10% |

| Female | 314 | 54.90% | |

| Age | 18–25 | 153 | 26.70% |

| 26–35 | 128 | 22.40% | |

| 36–45 | 113 | 19.80% | |

| 46–55 | 75 | 13.10% | |

| 55–65 | 72 | 12.60% | |

| >65 | 31 | 5.4% | |

| Education | Junior high school | 38 | 6.60% |

| Senior high school | 162 | 28.30% | |

| Vocational/College | 162 | 28.30% | |

| Undergraduate | 185 | 32.30% | |

| Postgraduate | 25 | 4.40% | |

| Job | Professionals | 89 | 15.60% |

| Civil servants | 86 | 15.00% | |

| Managers of enterprises | 78 | 13.60% | |

| General staff of enterprises | 71 | 12.40% | |

| Service/sales staff | 55 | 9.60% | |

| Primary sector staff | 31 | 5.40% | |

| Production, transport operators, and related personnel | 44 | 7.70% | |

| Unemployed | 2 | 0.30% | |

| Self-employed | 28 | 4.90% | |

| Retired/pensioner | 41 | 7.20% | |

| Students | 22 | 3.80% | |

| Other | 25 | 4.40% |

| Constructs | CA | OL | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SM | 0.781 | 0.827–0.842 | 0.782 | 0.695 |

| EV | 0.784 | 0.816–0.862 | 0.788 | 0.698 |

| PR | 0.771 | 0.812–0.848 | 0.772 | 0.686 |

| OM | 0.790 | 0.816–0.870 | 0.794 | 0.705 |

| SN | 0.834 | 0.804–0.831 | 0.834 | 0.667 |

| VA | 0.834 | 0.788–0.838 | 0.837 | 0.667 |

| CC | 0.761 | 0.803–0.843 | 0.763 | 0.676 |

| CB | 0.862 | 0.788–0.822 | 0.863 | 0.644 |

| SDG11 | 0.850 | 0.818–0.853 | 0.854 | 0.689 |

| SDG12 | 0.844 | 0.816–0.841 | 0.846 | 0.681 |

| CB | CC | EV | OM | PR | SDG11 | SDG12 | SM | SN | VA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CB | ||||||||||

| CC | 0.550 | |||||||||

| EV | 0.556 | 0.547 | ||||||||

| OM | 0.535 | 0.535 | 0.526 | |||||||

| PR | 0.553 | 0.547 | 0.575 | 0.588 | ||||||

| SDG11 | 0.537 | 0.499 | 0.540 | 0.494 | 0.575 | |||||

| SDG12 | 0.572 | 0.515 | 0.541 | 0.478 | 0.527 | 0.440 | ||||

| SM | 0.521 | 0.463 | 0.529 | 0.478 | 0.624 | 0.549 | 0.426 | |||

| SN | 0.560 | 0.553 | 0.488 | 0.532 | 0.602 | 0.516 | 0.494 | 0.521 | ||

| VA | 0.547 | 0.572 | 0.521 | 0.488 | 0.567 | 0.526 | 0.494 | 0.550 | 0.568 |

| Item | Excess Kurtosis | Skewness | VIF | Q2 | Factor Loading | Explained Variance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Construct 1: Social Marketing | 22.924% | |||||

| Factor 1: Social media | 5.803% | |||||

| SM1 | −0.917 | −0.214 | 1.629 | / | 0.743 | |

| SM2 | −0.656 | −0.218 | 1.583 | / | 0.732 | |

| SM3 | −0.869 | −0.157 | 1.649 | / | 0.754 | |

| Factor 2: Events | 5.744% | |||||

| EV1 | −0.882 | −0.117 | 1.645 | / | 0.734 | |

| EV2 | −0.951 | −0.134 | 1.723 | / | 0.720 | |

| EV3 | −0.785 | −0.258 | 1.559 | / | 0.768 | |

| Factor 3: Public Relations | 5.518% | |||||

| PR1 | −0.761 | −0.261 | 1.548 | / | 0.696 | |

| PR2 | −0.687 | −0.283 | 1.703 | / | 0.753 | |

| PR3 | −0.749 | −0.204 | 1.524 | / | 0.709 | |

| Factor 4: Other Media | 5.859% | |||||

| OM1 | −0.860 | −0.103 | / | 0.746 | ||

| OM2 | −0.696 | −0.215 | / | 0.763 | ||

| OM3 | −0.897 | −0.145 | / | 0.749 | ||

| Construct 2: The Influencing Factors | 20.847% | |||||

| Factor 5: Subjective Norms | 7.566% | |||||

| SN1 | −0.671 | −0.324 | 1.856 | 0.224 | 0.741 | |

| SN2 | −0.829 | −0.238 | 1.788 | 0.201 | 0.774 | |

| SN3 | −0.815 | −0.185 | 1.827 | 0.209 | 0.735 | |

| SN4 | −0.775 | −0.200 | 1.701 | 0.218 | 0,705 | |

| Factor 6: Value | 7.616% | |||||

| VA1 | −0.642 | −0.286 | 1.662 | 0.180 | 0.715 | |

| VA2 | −0.582 | −0.302 | 1.865 | 0.235 | 0.709 | |

| VA3 | −0.722 | −0.271 | 1.811 | 0.211 | 0.746 | |

| VA4 | −0.702 | −0.258 | 1.842 | 0.206 | 0.758 | |

| Factor 7: Communication Channel | 5.665% | |||||

| CC1 | −0.706 | −0.223 | 1.467 | 0.177 | 0.706 | |

| CC2 | −0.846 | −0.103 | 1.586 | 0.221 | 0.716 | |

| CC3 | −0.714 | −0.232 | 1.580 | 0.163 | 0.784 | |

| Construct 3 | 9.082% | |||||

| Factor 8: Consumer Behavior | 9.082% | |||||

| CB1 | −0.745 | −0.239 | 1.778 | 0.233 | 0.692 | |

| CB2 | −0.694 | −0.182 | 1.800 | 0.213 | 0.705 | |

| CB3 | −0.887 | −0.236 | 1.843 | 0.200 | 0.746 | |

| CB4 | −0.812 | −0.217 | 1.955 | 0.253 | 0.705 | |

| CB5 | −0.949 | −0.184 | 1.997 | 0.174 | 0.775 | |

| Construct 4 | 15.677% | |||||

| Factor 9: SDG11 | 7.848% | |||||

| 11-1 | −0.871 | −0.167 | 1.936 | 0.145 | 0.795 | |

| 11-2 | −0.718 | −0.221 | 1.848 | 0.170 | 0.732 | |

| 11-3 | −0.738 | −0.325 | 1.850 | 0.168 | 0.743 | |

| 11-4 | −0.823 | −0.205 | 2.020 | 0.174 | 0.757 | |

| Factor 10: SDG12 | 7.829% | |||||

| 12-1 | −0.806 | −0.212 | 1.856 | 0.145 | 0.766 | |

| 12-2 | −0.885 | −0.144 | 1.907 | 0.162 | 0.754 | |

| 12-3 | −0.835 | −0.298 | 1.823 | 0.137 | 0.751 | |

| 12-4 | −0.678 | −0.203 | 1.849 | 0.158 | 0.745 |

| Path | Stdev | Std | T Value | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1a: SM→SN | 0.044 | 0.171 | 3.873 | 0.000 |

| H1b: SM→VA | 0.042 | 0.217 | 5.130 | 0.000 |

| H1c: SM→CC | 0.044 | 0.106 | 2.428 | 0.015 |

| H2a: EV→SN | 0.042 | 0.129 | 3.080 | 0.002 |

| H2b: EV→VA | 0.044 | 0.182 | 4.188 | 0.000 |

| H2c: EV→CC | 0.044 | 0.218 | 4.930 | 0.000 |

| H3a: PR→SN | 0.045 | 0.251 | 5.633 | 0.000 |

| H3b: PR→VA | 0.045 | 0.202 | 4.460 | 0.000 |

| H3c: PR→CC | 0.044 | 0.178 | 4.019 | 0.000 |

| H4a: OM→SN | 0.041 | 0.199 | 4.894 | 0.000 |

| H4b: OM→VA | 0.045 | 0.145 | 3.225 | 0.001 |

| H4c: OM→CC | 0.042 | 0.205 | 4.927 | 0.000 |

| H5: SN→CB | 0.047 | 0.158 | 3.369 | 0.001 |

| H6: VA→CB | 0.044 | 0.132 | 3.000 | 0.003 |

| H7: CC→CB | 0.044 | 0.124 | 2.810 | 0.005 |

| H8: CB→SDG11 | 0.033 | 0.462 | 14.035 | 0.000 |

| H9: CB→SDG12 | 0.032 | 0.491 | 15.435 | 0.000 |

| Mediator Variable | Path | Std | Stdev | T Statistics | 95% CI of the Difference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LL | UL | |||||

| SN | SM→SN→CB | 0.027 | 0.011 | 2.509 * | 0.009 | 0.050 |

| EV→SN→CB | 0.020 | 0.009 | 2.307 * | 0.006 | 0.040 | |

| PR→SN→CB | 0.040 | 0.014 | 2.827 ** | 0.015 | 0.070 | |

| OM→SN→CB | 0.032 | 0.012 | 2.655 ** | 0.011 | 0.057 | |

| VA | SM→VA→CB | 0.029 | 0.011 | 2.519 * | 0.009 | 0.054 |

| EV→VA→CB | 0.024 | 0.010 | 2.419 * | 0.007 | 0.047 | |

| PR→VA→CB | 0.027 | 0.011 | 2.333 * | 0.008 | 0.053 | |

| OM→VA→CB | 0.019 | 0.009 | 2.230 * | 0.005 | 0.038 | |

| CC | SM→CC→CB | 0.013 | 0.008 | 1.703 | 0.002 | 0.031 |

| EV→CC→CB | 0.027 | 0.012 | 2.327 * | 0.007 | 0.053 | |

| PR→CC→CB | 0.022 | 0.009 | 2.342 * | 0.006 | 0.043 | |

| OM→CC→CB | 0.025 | 0.010 | 2.416 * | 0.007 | 0.048 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chu, Y.; Sotiriadis, M.; Shen, S. Investigating the Impact of Social Marketing on Tourists’ Behavior for Attaining Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Sustainability 2025, 17, 6748. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156748

Chu Y, Sotiriadis M, Shen S. Investigating the Impact of Social Marketing on Tourists’ Behavior for Attaining Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Sustainability. 2025; 17(15):6748. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156748

Chicago/Turabian StyleChu, Yinuo, Marios Sotiriadis, and Shiwei Shen. 2025. "Investigating the Impact of Social Marketing on Tourists’ Behavior for Attaining Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)" Sustainability 17, no. 15: 6748. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156748

APA StyleChu, Y., Sotiriadis, M., & Shen, S. (2025). Investigating the Impact of Social Marketing on Tourists’ Behavior for Attaining Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Sustainability, 17(15), 6748. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156748

_Li.png)