1. Introduction

In the literature, issues related to the accessibility of public services, including medical services, occupy an important place in research in the fields of socio-economic geography, urban planning, health policy, and spatial planning. The growing importance of the issue of accessibility is due to its direct impact on the quality of life of the population, the level of health security, and social equity in access to basic services. Ensuring equitable and effective access to healthcare is also recognized as a crucial component of sustainable development strategies, as it directly influences social cohesion, economic resilience, and environmental efficiency through optimal spatial distribution of services. Therefore, undertaking research on the accessibility of medical services in Olsztyn County required an analysis of existing scientific achievements in this field and an identification of the methods and indicators most commonly used in assessing spatial accessibility. The purpose of this literature review is to organize and discuss key definitions of the concept of accessibility, present the main methodological approaches used in the analysis of public services, and identify categories of indicators used to measure accessibility, with particular emphasis on health services. Incorporating these aspects into local and regional development strategies contributes to improving the overall quality of life while promoting sustainable, inclusive, and spatially balanced growth. Taking into account previous research allows not only for the determination of applicable methodological standards, but also for the identification of areas that require further analysis, which is an important justification for the research approach adopted in this study.

In today’s dynamic society, the issue of service accessibility, such as to schools and cultural facilities or technology, occupies an increasingly important place in debates on quality of life and local community development. Services play a key role in meeting residents’ basic life needs by affecting their daily functioning and overall well-being. Among the wide range of services, healthcare services are frequently identified as key determinants of quality of life and population health outcomes [

1]. Nevertheless, the relationship between the availability of healthcare services and physical and mental health is context-dependent and may vary notably in rural or underserved areas where other factors such as socioeconomic status, transport accessibility, and social capital play crucial roles [

2].

The accessibility of healthcare services is vital to ensuring effective health care. The ease of access to these services is influenced by numerous factors, including the location of medical facilities, the availability of public transport, and service affordability. Therefore, analysis of access to medical services plays a key role in urban planning and health system management to ensure better access to services for the population.

This study focuses on the accessibility of healthcare services in Olsztyn County, located in the Warmian–Masurian Voivodeship in Poland. As a hub of economic, cultural, and scientific activity in the region of Warmia and Mazury, Olsztyn County can be regarded as a starting point for a comprehensive analysis of the accessibility of healthcare services in the entire region. The objective of the proposed approach to analyzing the accessibility of public healthcare services was to identify areas with low access to these services by using spatial data and Geographic Information System (GIS) tools and to guide potential solutions and strategies to improve the current situation. Effective management of the network of healthcare facilities and the optimization of their location can reduce patient waiting times for primary care appointments and increase the effectiveness of the entire healthcare system in Olsztyn County.

The availability of healthcare services was analyzed based on public access to hospitals, pharmacies, dispensaries, outpatient clinics, dental clinics, and ophthalmology clinics. These facilities represent the most popular types of medical services, and they can be regarded as basic healthcare facilities.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Accessibility of Public Services

Accessibility is a term that encompasses various aspects of satisfaction derived from the use of specific goods and services, generally referred to as resources [

3,

4]. The accessibility of resources is an important social problem and a measure of socioeconomic development. According to Sen [

5], lack of access to resources can be equated with lack of resources. Given the development of transport and trade, this point of view seems appropriate. In this approach, high availability of various resources can be a measure of quality of life; therefore, it is an important element of social policy [

6]. In turn, guaranteed and equal access to services of general interest (SGI) is a statutory duty of the authorities at various levels of government [

7]. The availability of SGI has also been investigated by researchers to identify the most effective methods of evaluating the accessibility of these services [

8,

9,

10].

In the literature, the concept of geographical accessibility has been defined as a measure of the potential of a given location to interact with other places in space, depending on the number and importance of available resources and the difficulty (e.g., distance or time) of reaching them [

11]. It reflects the possibility of acquiring specific resources, including services [

12]. Spatial accessibility is a specific variant of this concept, and it can combine economic, social, and physical factors as well as other factors that lead to the achievement of satisfaction [

13]. Spatial accessibility is related mainly to the organization of space, in particular the distribution of services and places where humans perform activities such as work, leisure, or shopping. This dimension of accessibility is often considered in a broader context to include the spatial differentiation of society and phenomena such as poverty and exclusion that affect various social groups, including persons with disabilities or the elderly [

2,

14].

The extent to which residents have access to public facilities, services, or green spaces is a key determinant of quality of life [

15]. Analyses of access to public services and the resulting optimization solutions can significantly contribute to the creation of spaces that are accessible to all members of the public [

16]. Such analyses also provide essential information for assessing residential safety, particularly in crisis situations such as extreme weather events or military conflicts [

17].

The accessibility of public services is most often considered in the context of medical services. Researchers rely on accessibility indicators that integrate distance with the number of hospital beds and morbidity data [

18] or the accessibility of medical services with virtual visits [

19]. Access to educational services has also attracted considerable research interest. The distribution of primary education facilities in urban areas has been investigated by numerous authors [

20,

21,

22]. Recreational and sports facilities are yet another category of public amenities that have been frequently studied in the context of accessibility [

23,

24]. The cited authors relied on different methods and benchmarks for measuring accessibility. The choice of these methods and indicators is determined not only by the research goal, but also by the type of services, their geographic location, and target groups to which these services are addressed [

25].

In most cases, accessibility is measured in terms of the distance that must be traveled to gain access to a specific good or service. Accessibility that is expressed by distance can be referred to as physical accessibility. This distance is measured in a straight line or based on the distance covered by transport routes [

26]. The time needed to access a specific good or service is increasingly often regarded as a measure of accessibility. Accessibility can also be measured in terms of the cost associated with gaining access to a good or service. The period of time over which a service is available is a key measure of the accessibility of IT services or databases [

27].

According to the reviewed literature, the following categories of accessibility can be identified based on the indicators that are most frequently used to evaluate the accessibility of public services:

1. Physical accessibility, which is usually assessed based on the location, distribution, and density of public services in a given community. Physical accessibility is also frequently analyzed in the context of access to public transport and support services for people with disabilities [

28].

2. Financial accessibility, which is assessed mainly based on service costs. These analyses rely on indicators such as public service prices relative to household incomes in different social groups [

29]. The availability of financial aid schemes, including social benefits and tax deductions for lower income groups, and the ease of access to financial services, is a variant of financial accessibility [

30].

3. Information accessibility, which is assessed based on the reliability and readability of information. This measure is applied to determine whether information about public services is clear, available, and understandable to different social groups, including less educated individuals or persons who are not familiar with legal and administrative terms. Access to the Internet and digital technology is a variant of information accessibility that enables community members to access public services such as online registration or digital forms [

31].

4. Cultural and social accessibility, which describes the extent to which ethnic minorities and migrants have access to public services. This type of accessibility is measured based on the accessibility and delivery of public services, including access to documents, registration services, and integration support, for different ethnic and linguistic groups [

32].

Since the above categories are interrelated and usually directly influence each other, it appears that the studied concepts can be most effectively described in terms of spatial accessibility, which can account for the multiplicity and complexity of access to public services when supported by GIS analyses. Geographic Information System tools can be effectively applied to identify the distribution of public facilities, as well as their accessibility in different geographic areas and for different socioeconomic groups.

Accessibility is generally determined by measuring the distance between a person’s place of residence and the nearest public facilities, such as schools, healthcare centers, and public service outlets. Accessibility is also often described with the use of methods such as isochrone mapping analyses, which identify areas where public services can be accessed within a specific time range. These methods are often augmented with socio-technical tools (questionnaires and surveys) that expand our understanding of the limitations and difficulties associated with access to public services. The use of infrastructure data, such as road networks, public transport routes, or the availability of parking spaces in the vicinity of public facilities, is also one of the primary tasks of GIS tools. During spatial analyses, the above information can also be integrated with socioeconomic factors such as income, education, or social status to facilitate the identification of inequalities in access to public services.

However, physical accessibility appears to be of key importance in the discussed context. Assessment of the physical accessibility of public services, particularly the location and availability of public facilities, plays the most important role in analyses aimed at determining whether residents have satisfactory access to the services they need [

33]. According to Lynch [

34], accessibility is a time issue, but it also depends on the “attractiveness” of the itineraries and the ease with which a given route can be identified.

In this study, the authors focused on spatial accessibility, which is widely recognized in the literature as one of the most commonly applied and methodologically robust dimensions of access to public services, including healthcare. Spatial accessibility—defined as the spatial relationship between service locations and the residences of potential users—plays a fundamental role in shaping actual access to services, particularly at local and regional levels [

11]. Unlike other dimensions of accessibility, such as financial, informational, or organizational, which require detailed individual-level data on income, awareness, or administrative procedures, spatial accessibility can be effectively assessed using publicly available spatial datasets and GIS tools that incorporate distance, travel time, and infrastructure layout.

In the context of Olsztyn County—a region characterized by dispersed settlement patterns and limited healthcare availability in many rural municipalities—spatial accessibility is especially relevant. Due to data limitations and resource constraints, it was not feasible to include other dimensions of accessibility in the present analysis. However, spatial accessibility offers a practical and evidence-based starting point for identifying structural inequalities in service provision and can help guide future research incorporating broader dimensions of access as data availability improves.

Public service accessibility has been widely studied in socioeconomic geography, where the geography of services constitutes a distinct subfield [

35]. The topic also appears in disciplines such as public management, urban planning, sociology, and economics [

26]. Depending on the nature of the service, target population, and regional context, various analytical approaches have been developed [

36,

37]. Among these, geospatial methods remain the most common and effective tools, especially for evaluating access to physical infrastructure such as hospitals, schools, or public transport [

12,

38]. Geospatial analyses rely on georeferenced data to examine spatial relationships between users and services, often using tools such as network analysis, distance-based measures, or isochrone mapping [

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44]. These techniques allow for the assessment of travel time, distance, and infrastructure distribution, offering a clear view of territorial inequalities in service access. In studies focusing on users’ perceptions or social barriers, qualitative methods such as surveys or interviews are also employed [

45,

46,

47,

48], but their application typically requires a different research design. Given the spatial nature of the research problem and the availability of spatial data, this study adopts a GIS-based approach to assess the accessibility of healthcare services in Olsztyn County.

2.2. Accessibility Indices

Accessibility indices are calculated to quantify public service accessibility [

49]. Both simple indices and more complex mathematical models can be used for this purpose [

13,

50].

The Potential Accessibility Index measures potential access based on the geographic proximity and density of infrastructure in a given area.

The Service Accessibility Index is calculated to determine the ease of access to public facilities such as schools, hospitals, and offices in a given area. In these analyses, public service accessibility is evaluated based on infrastructure data, such as road networks, public transport routes, and the availability of parking spaces in the vicinity of public facilities.

Multidimensional Accessibility Indices incorporate numerous factors, including physical distance, travel time, travel cost, disabled access, and digital accessibility (such as e-services).

The Equal Access Indicator accounts for socioeconomic factors such as income, education, and social status in analyses of public service accessibility to evaluate inequalities in access to public services [

51,

52].

Research on service accessibility employs a range of methods, from geospatial analyses to surveys, econometric models, and simulation techniques. Each contributes to a broader understanding of how different factors influence accessibility and how service provision can be improved. Future research may benefit from integrating these methods to develop more comprehensive approaches that account for both spatial and socioeconomic dimensions.

Although numerous methods and indices have been developed to measure public service accessibility, many require detailed data that are not always available at the local level. For this reason, spatial accessibility remains a particularly useful and feasible dimension for local-scale analyses. In regions such as Olsztyn County—characterized by a dispersed settlement structure and limited infrastructure in some rural municipalities—there is a need for practical tools adapted to available data. This study responds to that need by applying a GIS-based methodology to assess healthcare accessibility across municipalities. The following section outlines the methodological framework used in this analysis.

3. Data and Methods of Assessment of the Accessibility of Medical Services in Olsztyn County in Poland

3.1. Source Data

The study covered Olsztyn County and local administrative units at the NUTS 4 and 5 level, i.e., 12 municipalities and the city of Olsztyn. The study area was selected due to its geographic specificity. Olsztyn County covers areas with relatively high population density and high levels of urbanization, as well as areas where both of these parameters are low. The above can be attributed to natural features (extensive forests and numerous lakes) and economic indicators (low GDP in the voivodeship of Warmia and Mazury). These variations supported the identification of significant differences in public access to medical services and the validation of the developed procedure. It should be noted that the accessibility of medical services was evaluated using a point method based on the location of healthcare facilities. In order to improve the readability and applicability of the data, the obtained results were presented as mean values for the local administrative units examined. The locations of the analyzed units are presented in

Figure 1.

Data for the analysis were sourced from online database platforms, including OpenStreetMap, BDOT10k, and address databases, sources of detailed geospatial data that have broad applications in many scientific fields, including hydrology, climatology, and agriculture [

53,

54].

The BDOT10k database of topographic objects contains key data for analyzing the accessibility of pharmacies in Olsztyn country. The database provides detailed topographic information for accurate spatial analyses [

55]. This resource can be used to acquire and process information about the locations of road networks and buildings [

56]. These data can be applied to identify areas with low access to healthcare facilities and to determine the distances between the key objects in the analysis.

The locations of healthcare facilities were determined by address geocoding. Address data were acquired from databases (including platforms such as

https://rejestry.ezdrowie.gov.pl/ra/search/public (accessed on 7 January 2024) and translated into X and Y coordinates for analytical purposes [

57]. Geocoding plays a key role in various market segments, where textual addresses are transformed into geographic coordinates to determine the spatial location of clients, branches, and competitors [

58]. Geocoding tools facilitate the localization of public services and they can be used to evaluate service distribution relative to the needs of local communities.

Each of these data sources has strengths and limitations. An integrated approach that accounts for the scope, reliability, and complementarity of the supplied information is required to ensure that these data are optimally used in an evaluation of access to medical services in Olsztyn County.

The data selected for the analysis were validated by cross-coverage (the coverage of geolocation data was cross-validated with information from several sources). The only (minor) discrepancies were identified in OSM data (for two objects). Therefore, the acquired data were considered reliable.

3.2. Research Methodology

The analysis was carried out in two stages. In the first stage, the potential attractiveness of healthcare services was evaluated based on the distance between residential buildings and objects belonging to different categories of medical services and the population of each municipality. Due to the limited availability of detailed spatial data, the analytical approach adopted was the most feasible solution in the study conditions. One of the main challenges in assessing the accessibility of services is the difficulty of precisely determining the actual place of residence of users and their demand for various categories of medical services. The lack of detailed demographic and mobility data at the individual level means that studies of this type often use aggregate information, such as the number of residents within administrative units and the distribution of residential buildings. Spatial accessibility studies are most often based on simplified methods, which, although less precise, allow for a reliable picture of service accessibility at the local and regional levels, providing valuable information to support the process of spatial planning and service infrastructure management. Detailed locations of residential buildings and the populations of the analyzed municipalities were used in the present study. The centroids of residential buildings and healthcare facilities were determined based on BDOT10k data. The OSM database and address data available online in public registers of healthcare facilities (such as

https://rejestry.ezdrowie.gov.pl/ra/search/public (accessed on 7 January 2024) were also used in the study. These data were applied to calculate the indicators of potential demand for services (

IA) according to Equation (1):

where

IA—indicator of potential demand for services.

i—municipality in Olsztyn County.

j—type of service in the overall number n of the analyzed services.

P—population of the analyzed municipality.

—average distance between residential buildings and service facilities j.

The calculated indicator was used to evaluate the average distances between healthcare facilities and potential users in the analyzed municipalities. For the purposes of the study, healthcare facilities were defined as all buildings where medical services are provided, not as economic and administrative units. For example, a hospital may provide medical services in several buildings, including buildings that are separated by a considerable distance. In the present analysis, all buildings were considered as separate objects. The determination of indicator IA in all municipalities of Olsztyn County and their classification makes it possible to identify areas with high population density, long distances between residential buildings and services, and, consequently, low accessibility of healthcare services.

In the second stage of the study, the attractiveness of objects representing a given category of medical services was evaluated based on the factors that significantly affect access to these services. In this study, the attractiveness of medical facilities is understood as a potentially higher probability of users choosing a given facility due to its location and functional environment. The attractiveness index determines the extent to which a given place of healthcare service provision is favorably located in terms of transport accessibility, proximity to other services, the number of residential buildings in the vicinity, and distance from competing facilities of the same category. The more favorable these conditions are, the greater the likelihood that a given facility will be chosen by potential patients, regardless of its formal quality parameters.

The definition adopted in the study refers to the approach used in analyses of the location of public and commercial services, where spatial attractiveness is treated as a function of favorable neighborhood, transport accessibility, and potential demand generated by surrounding residential development [

10,

59,

60]. The following factors were taken into consideration:

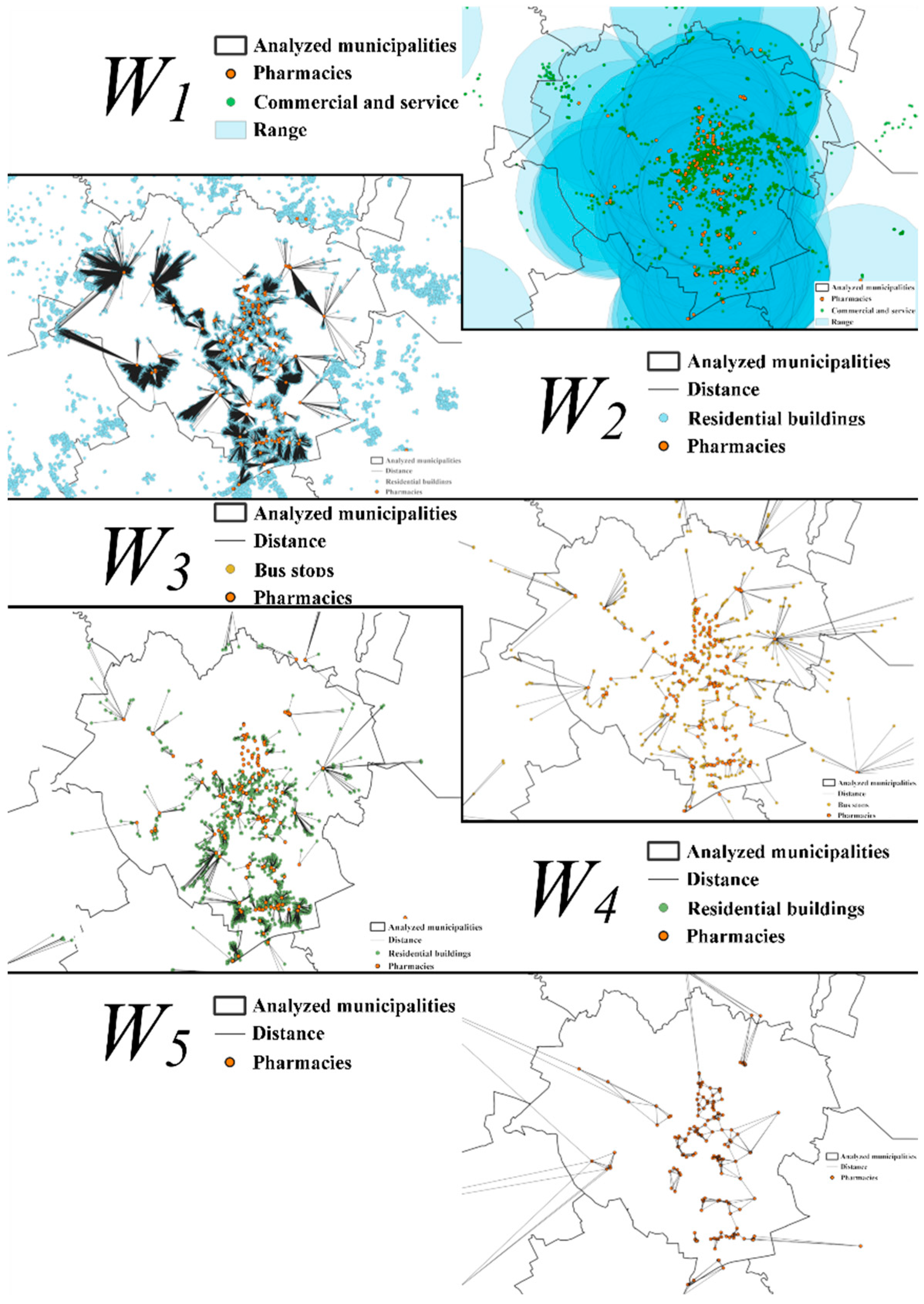

W1—number of retail and service outlets within a 3 km radius of the analyzed healthcare facilities. This parameter was used to determine the attractiveness of an object based on the availability of other services and amenities in the vicinity.

W2—number of residential dwellings situated closest to the analyzed object in the group of service facilities of a given type.

W3—distance between a public transport stop and the nearest object. This measure was used to evaluate the attractiveness of an object based on the accessibility of public transport.

W4—distance between a car park and the nearest object. Similarly to W3, this measure was used to evaluate the attractiveness of an object based on the availability of private transport.

W5—average distance to the three closest objects of the same category. This measure was used to assess the competitive advantage of other service facilities and potential problems with competing for clients.

Figure 2 presents the procedure of calculating W factors for pharmacies in a selected local administrative unit—the city of Olsztyn.

The calculated factors were standardized and averaged, and they were used to evaluate the attractiveness of service facilities in the final assessment. Five factors were considered at this stage of the analysis, but the number of factors can differ depending on the availability of data. These factors are selected based on the specificity of the examined services and the spatial characteristics of the areas in which they are located. The strength of the effect exerted by each factor on the attractiveness of service facilities will be determined in future research. In the present study, the calculated factors were assigned identical weights, but different weights are also possible. The corresponding weights can be determined by conducting surveys or performing detailed analyses of the applicable parameters, such as sales volume.

In the final stage of the study, the municipalities of Olsztyn County were evaluated by calculating the indicators of accessibility of medical services (

AMS) based on population, distance between residential buildings and healthcare facilities, and the ease of access and attractiveness of the studied objects. The indicator

AMS was calculated using the Equation (2):

where

Each object identified in a given category of objects was evaluated. The values of indicator AMS ranged from 0 to 1. Objects with AMS values closer to 1 were characterized by greater importance in the studied area. Values closer to 1 indicate that the analyzed object has many potential users and is characterized by high spatial attractiveness.

The described approach supported the identification of differences in the evaluated municipalities. The proposed procedure can also be used to formulate policy guidelines with the aim of improving access to medical services and promoting the development of objects with low attractiveness scores.

4. Results

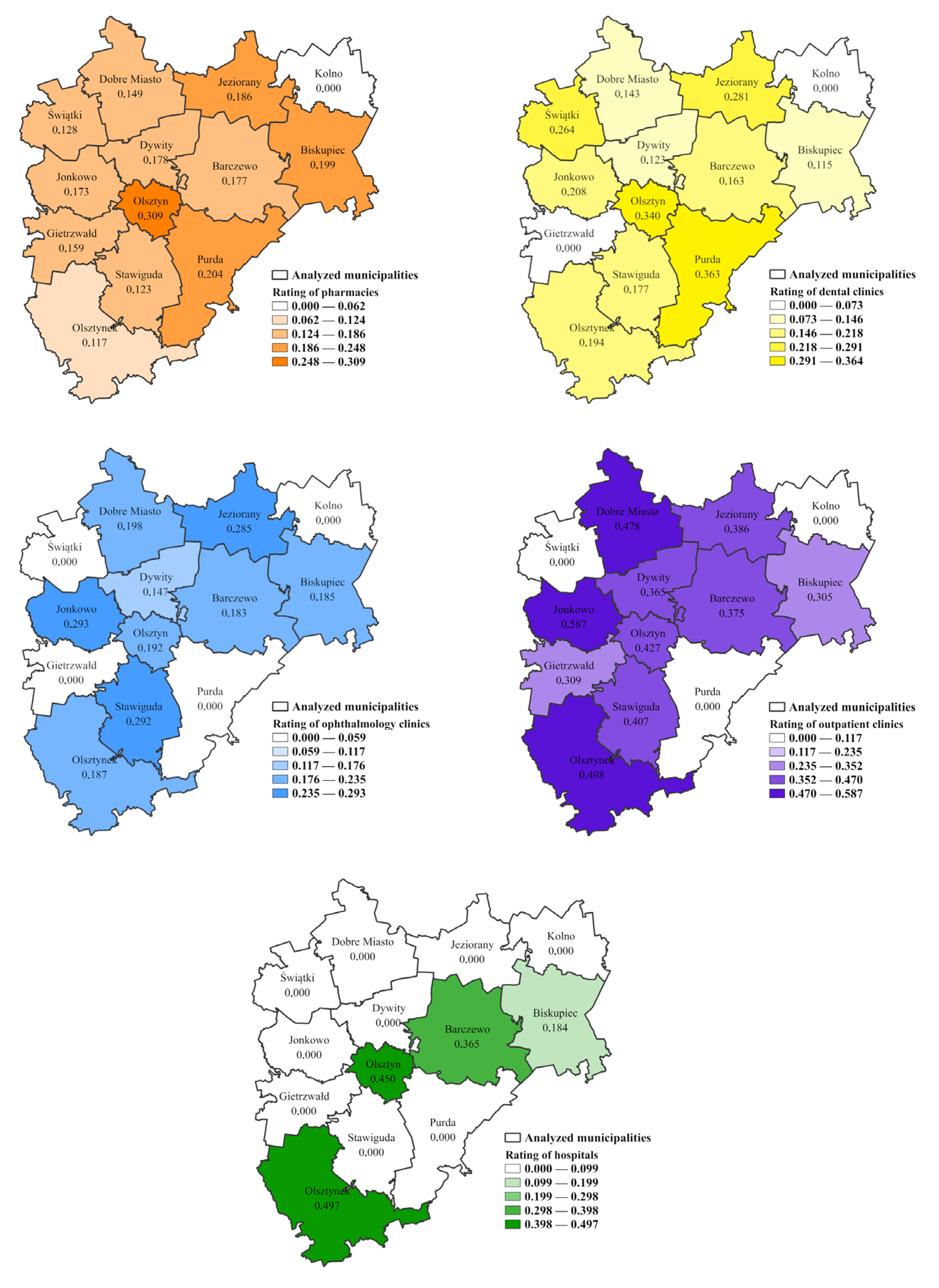

The objects in each category of medical services were evaluated and the results are presented in

Figure 3. The assessment relied on the Jenks method, which clusters data into groups to minimize variance within groups and maximize variance between groups [

61].

The highest concentration of facilities is in Olsztyn, which dominates in all categories, with the most hospitals, pharmacies, clinics, dental offices, and ophthalmology offices. High values were also recorded in Biskupiec, while in municipalities such as Kolno and Świątki, the availability of medical facilities is very limited—in some categories, there are no facilities at all.

These data confirm the tendency, known from the literature, for medical services to be concentrated in larger urban centers, which leads to a widening of the gap between the center and the periphery. The lack of basic medical facilities in rural municipalities increases the risk of health exclusion and limits the safety of residents in the event of sudden health needs.

To increase the readability of the assessment, the ratings in each category of medical services in the municipalities of Olsztyn County and in the city of Olsztyn were averaged and classified by the corresponding units, and the results are presented in cartograms in

Figure 4.

The highest rates were again recorded in Olsztyn and Biskupiec, which means not only a large number of facilities but also good transport accessibility and connection with accompanying services. Average values occurred in Olsztynek, Barczewo, and Dobre Miasto, and the lowest were in Kolno and Świątki.

The results indicate that it is not only the number of facilities that determines the availability of services, but also their location and infrastructure. The presence of parking lots, public transport stops, and other services enhances the attractiveness of facilities and actual access to health services. The lack of these elements in rural municipalities further exacerbates the problem of limited access to medical services.

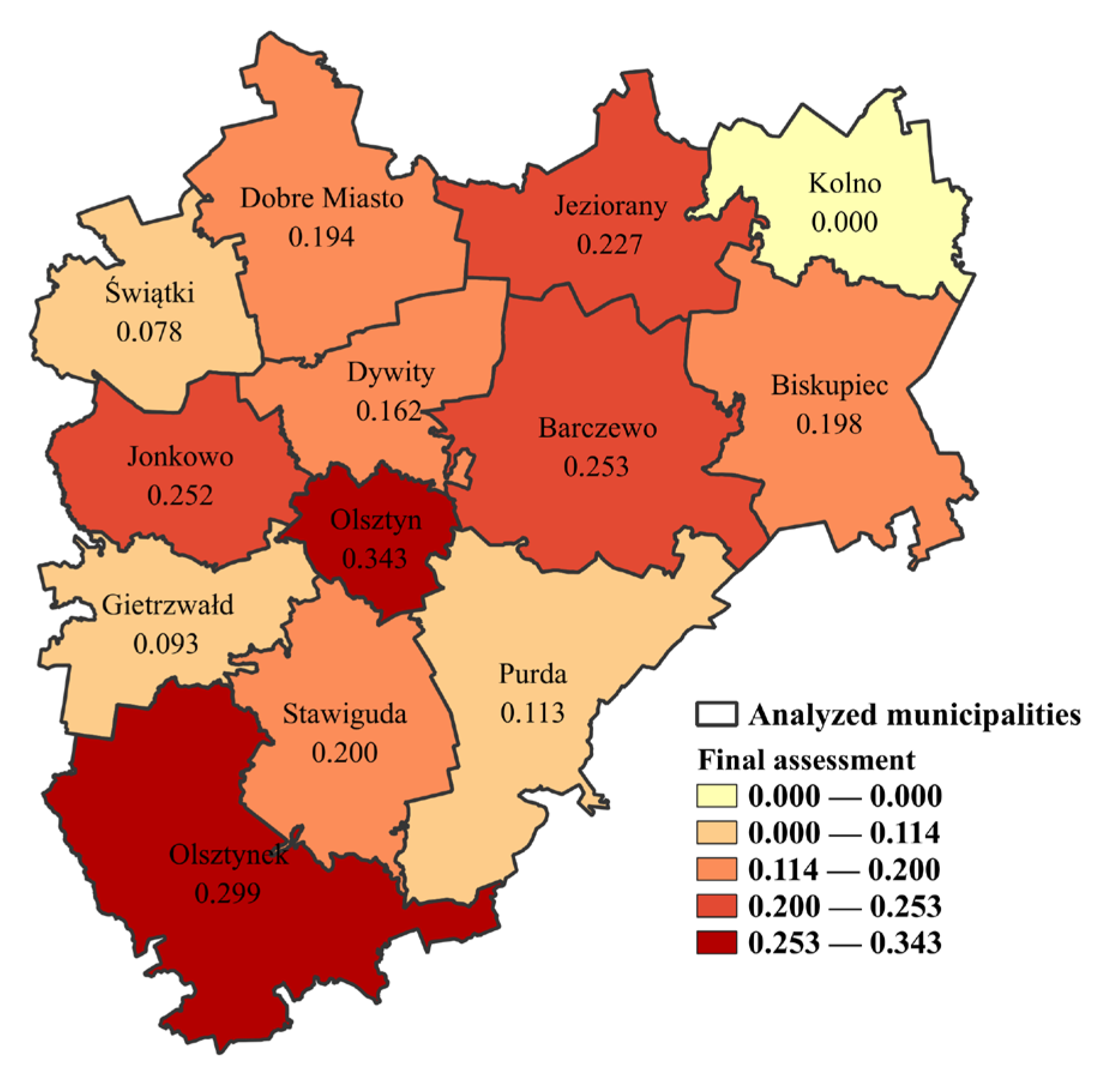

The results obtained in each category of medical services in the examined local administrative units, presented in

Figure 4, were averaged to visualize the overall accessibility of medical services in municipalities. The resulting scores were classified and the final assessment of access to medical services in Olsztyn County is presented in a cartogram in

Figure 5.

The highest values, exceeding 0.3, were obtained by Olsztyn (0.343) and Olsztynek (0.299), indicating very good access to medical services for the residents of these municipalities. Average values were recorded in municipalities such as Biskupiec and Barczewo, and the lowest in Kolno (0.000) and Świątki (0.078), which means very limited access to medical services.

The final AMS results clearly confirm the existence of significant differences in the level of access to medical services within the county. On the one hand, Olsztyn serves as a regional center for medical services with a high standard of infrastructure, while on the other hand, peripheral rural municipalities remain in a situation of deficit, which threatens equal access to health services. These results indicate the need for systematic planning of medical infrastructure development and support for public transport in municipalities with the lowest accessibility rates.

The analysis revealed clear differences in access to healthcare services in the municipalities of Olsztyn County. Urban areas such as the city of Olsztyn have extensive access to various medical services and support infrastructure, which increases living standards and quality of life. In contrast, rural municipalities such as Kolno and Świątki are characterized by poor access to the analyzed categories of medical services. The results of the evaluation were largely influenced by the number of objects and the transport accessibility in the examined local administrative units. The numbers of objects and transport amenities are presented in

Table 1. The city of Olsztyn topped the ranking with 161 pharmacies, 22 hospitals, 15 dental clinics, 33 ophthalmology clinics, and 19 outpatient clinics. Olsztyn has the most developed health infrastructure and its residents have easy access to primary medical services. In addition, high numbers of retail and service outlets (1491), car parks (1464), and public transport stops (396) increase the attractiveness and accessibility of healthcare facilities in the city.

In the group of analyzed municipalities, Biskupiec received the highest scores in all evaluated categories. Biskupiec has 12 pharmacies, 4 hospitals, 14 dental clinics, and 11 ophthalmology clinics; therefore, the local residents have ample access to healthcare services. This municipality also has 158 retail and service outlets and 39 car parks, which promote local access to medical services.

The municipality of Kolno does not operate any healthcare facilities, and it received the lowest score in the classification. There are 761 residential buildings and 23 retail and service outlets in Kolno, but due to the absence of health infrastructure, the residents have to travel to other municipalities to access basic medical services.

Świątki is yet another municipality with low access to medical services. This municipality has only one pharmacy and one dental clinic, which indicates that local residents have limited access to health care. Due to the absence of hospitals, ophthalmologists, and outpatient clinics, the inhabitants of Świątki have to rely on the services provided in the neighboring municipalities.

The standardized values of

W factors describing the accessibility of healthcare facilities in the analyzed municipalities are presented in

Table 2. These values can be used to formulate guidelines for improving access to medical services in Olsztyn County.

The accessibility of outpatient clinics, pharmacies, dental services, and ophthalmology clinics should be improved in Kolno. The municipality of Świątki received low scores for access to outpatient clinics, hospitals, and ophthalmologists because the residents have to travel to other municipalities to access these medical services. Public access to hospitals should be improved in Jeziorany and Dobre Miasto. Similar analyses can be performed in all examined administrative units.

5. Discussion and Summary

The present study was undertaken to evaluate the accessibility of public services, in this case healthcare services, in the municipalities of Olsztyn County. The analysis of access to medical services in Olsztyn County revealed significant differences between urban and rural municipalities. Olsztyn, the capital city of the region of Warmia and Mazury, is characterized by a large number of medical facilities and a well-developed support infrastructure, and its residents have nearly unlimited access to health care. A comprehensive health infrastructure with numerous pharmacies, hospitals, and dental and ophthalmology clinics significantly improves quality of life because the residents do not have to travel to other locations to access medical services. In contrast, rural municipalities such as Kolno and Świątki face serious challenges due to a shortage of local healthcare facilities. These municipalities do not have pharmacies, outpatient clinics, and—most importantly—hospitals; therefore, local healthcare access is significantly limited. The residents have to travel long distances to access the nearest medical facilities, which is not only time-consuming, but could also pose a health threat in medical emergencies.

The lack of support infrastructure such as car parks and public transport stops that facilitate access to medical facilities is an equally important problem. Municipalities such as Olsztyn have well-developed networks of car parks and bus stops, which provide the residents with easy access to healthcare centers. In contrast, in rural municipalities such as Kolno and Świątki, the number of car parks and stops is limited, which additionally restricts access to these facilities.

A certain limitation of the study is the scarcity of comprehensive data, including population data for the examined locations. The researchers had to rely on average and estimated values, which may lead to incomplete conclusions about the accessibility of medical services. Subjective aspects of the accessibility of medical services, such as users’ experiences and perceptions of service quality, were not examined. It should be noted that the quality and effectiveness of healthcare services and customer satisfaction levels were not included in the analysis. The measurements were mainly based on the distance between medical facilities and between medical facilities and residential buildings, and on the availability of support infrastructure, which could oversimplify the overall picture of access to medical services by disregarding issues such as overcrowding and the availability of medical personnel.

Another important consideration is that the analyzed categories of medical services are not of equal significance. The authors are aware of this fact and this issue will be addressed in the future. The final assessment was based on the sum of scores in each service category, suggesting that all categories were assigned equal weight. Obviously, most consumers would argue that facilities such as hospitals should be prioritized over pharmacies. However, this raises a question that the authors cannot answer at this stage of the analysis, namely which is more important: the availability of advanced medical services or access to primary health care services that are often needed? Since this question cannot be answered due to the absence of scientific evidence, the analyzed factors were examined separately and the obtained scores were summed up in the final assessment.

Despite the cognitive value of the analyses, the study has several significant limitations. First, the spatial data on the location of medical services and infrastructure elements come from the OpenStreetMap (OSM) database and public registers. Although OSM data is highly up-to-date and widely used in spatial analyses, its completeness and accuracy may vary depending on the type of area. The literature indicates that in rural and peripheral areas, the OSM database is sometimes less accurate and may not fully reflect the actual distribution of all facilities [

62,

63]. Another significant limitation is the lack of information on the actual demand for medical services in municipalities. Information on the health status of residents or their individual preferences may limit the ability to fully reflect the actual diversity of demand for the services under study. Another limitation results from the simplification of the actual mobility pattern of residents. In reality, the availability of services also depends on the availability of pedestrian infrastructure and spatial barriers (e.g., rivers, forest areas, and railroad crossings). Failure to take these into account may in some cases overestimate or underestimate the level of accessibility determined in the analysis. Future studies plan to extend the analysis to include subjective components and data obtained from surveys and mobile traffic registers. Despite these problems and limitations, it should be emphasized that the study relied on a novel approach that integrates geospatial technologies such as GIS with multidimensional accessibility analyses, where both physical and socioeconomic factors are taken into consideration. These innovative tools provide more accurate and comprehensive insights into the accessibility of public services in Olsztyn County, which significantly contributes to an improvement in quality of life and the effective management of health infrastructure in the region.

To increase the reliability of the results, a simplified sensitivity analysis was performed consisting of testing alternative weighting options in the AMS index. In the first option, equal weights were assigned to all five factors, while in the second option, the weight of the factor of the number of residential buildings in the vicinity of the facility (W4) was doubled. In both cases, the results were similar to the baseline version, and changes in accessibility classification occurred only in municipalities with the lowest AMS values. This confirms the relative stability of the results and the correctness of the model assumptions. At the same time, it points to the need for more in-depth testing in future studies, taking into account user preferences or expert analyses when selecting weights.

It should also be noted that the analysis was static in nature and did not take into account factors that vary over time, such as traffic intensity, waiting times for appointments, opening hours of facilities, or the availability of appointments in registration systems. In practice, the actual availability of medical services is a complex and dynamic phenomenon. However, due to the lack of comprehensive information on the scope of services, the number and type of services, or the hours of availability of services, etc., a certain simplification was applied in the study. However, it provides results that may indicate the availability of basic medical services and even the possibility of obtaining assistance in emergency situations. It also provides an answer as to which municipalities covered by the study should be subject to an in-depth analysis.

The study revealed that urgent action is needed in municipalities with low access to healthcare services, particularly to expand medical and support infrastructure. New pharmacies, dispensaries, and outpatient clinics, as well as improved access to public transport could significantly improve the availability of key healthcare services. In particular, public–private partnerships and investments in the healthcare sector could contribute to sustainable development and equal access to medical services in all municipalities of Olsztyn County.

The identified differences between municipalities call for the implementation of a long-term development strategy in municipalities with low values of the accessibility indicator, such as Kolno and Świątki, to provide the residents with equal access to health care and support infrastructure. Such actions are essential not only for achieving social equity but also for building spatially balanced, healthy, and resilient communities, which are key objectives for sustainable development policy at local and regional levels.

6. Conclusions

Analysis of the average value of the index of access to medical services from all five factors (AMS) revealed considerable differences between municipalities. The highest values of this indicator were determined in the municipalities of Olsztyn (AMS = 0.343) and Olsztynek (AMS = 0.299), which implies that their residents have very good access to medical services. Fast and easy access to these services contributes to improved public health and a higher standard of living.

There is room for improvement in municipalities with moderate access to medical services. Average values of the accessibility indicator could imply that these municipalities would benefit from investment in new medical facilities or public transport to provide local community members with better access to health care.

The municipalities of Dywity, Świątki, and Gietrzwałd are characterized by low access to medical services and the lowest values of the accessibility indicator. Their residents have limited access to health care. The number of medical services is lowest in Kolno. This problem should be urgently addressed by the local authorities.

Integrated remedial measures are needed to improve access to health care in municipalities with the lowest values of the accessibility indicator. Urgent action is required to expand the existing health infrastructure by supporting the construction of new outpatient clinics, pharmacies, and hospitals. To facilitate access to medical services, local authorities should also aim to improve public transport by introducing new lines, increasing the frequency of services, and modernizing bus stops and railway stations. Public–private partnerships could provide satisfactory results in this regard. Local authorities can significantly accelerate the development of health infrastructure by encouraging private investment and promoting the establishment of public–private partnerships in the medical sector.

The results of this study can be applied in various areas of social and economic life. They provide a reliable basis for decision-makers responsible for the local health infrastructure, urban planning, health policy, and the quality of life in Olsztyn County. Moreover, improving access to healthcare services is a fundamental element of sustainable territorial development strategies, contributing to a reduction in social inequalities, strengthening community well-being, and promoting spatially balanced growth. By relying on modern analytical tools and multidimensional accessibility analyses, the study contributes to an improvement in the effectiveness and equity of healthcare services.

Detailed analysis of access to medical services plays a key role in ensuring equal access to health care for all residents. Such analyses are undertaken to resolve spatial conflicts resulting from an imbalance between social and economic factors, which affects the location of healthcare facilities. By integrating accessibility analyses into sustainable development policies, it is possible to shape healthier, more inclusive, and socially cohesive communities, ultimately enhancing the quality of life for current and future generations. The results of the present study will make a significant contribution to the debate on the accessibility of medical services, and they will provide practical guidelines for decision-makers, planners, and healthcare professionals in the process of developing an effective and equitable healthcare system.

The findings of this study have important implications for the sustainable development of local communities in Olsztyn County. Equal access to healthcare services is a key dimension of social sustainability, directly influencing residents’ quality of life, social cohesion, and territorial equity. By identifying areas of healthcare exclusion and spatial disparities in service provision, the study provides a valuable evidence base for policy makers and urban planners seeking to design more inclusive, resilient, and balanced regional development strategies. Furthermore, improved access to healthcare can indirectly support environmental sustainability by reducing the need for long-distance travel for basic medical services, thereby lowering transport-related emissions. From a socio-economic perspective, investments in health infrastructure stimulate local economies, generate new jobs, and enhance the overall attractiveness of municipalities for both residents and potential investors. Finally, by integrating advanced GIS-based spatial analyses into healthcare planning, this research contributes to the development of innovative, data-driven management tools that can improve public service delivery and promote sustainable, healthy, and equitable communities in the long term.