Empowering Maritime Spatial Planning and Marine Conservation Efforts Through Digital Engagement: The Role of Online Platforms

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology: Criteria for Platform Overview

3. Insights for Further Discussion

3.1. Ocean Governance in Maritime Spatial Planning

3.1.1. Needs for Ocean Governance in MSP

3.1.2. Barriers to Ocean Governance in MSP

3.1.3. Enablers of Ocean Governance in MSP

3.2. Results of Platform Relevance

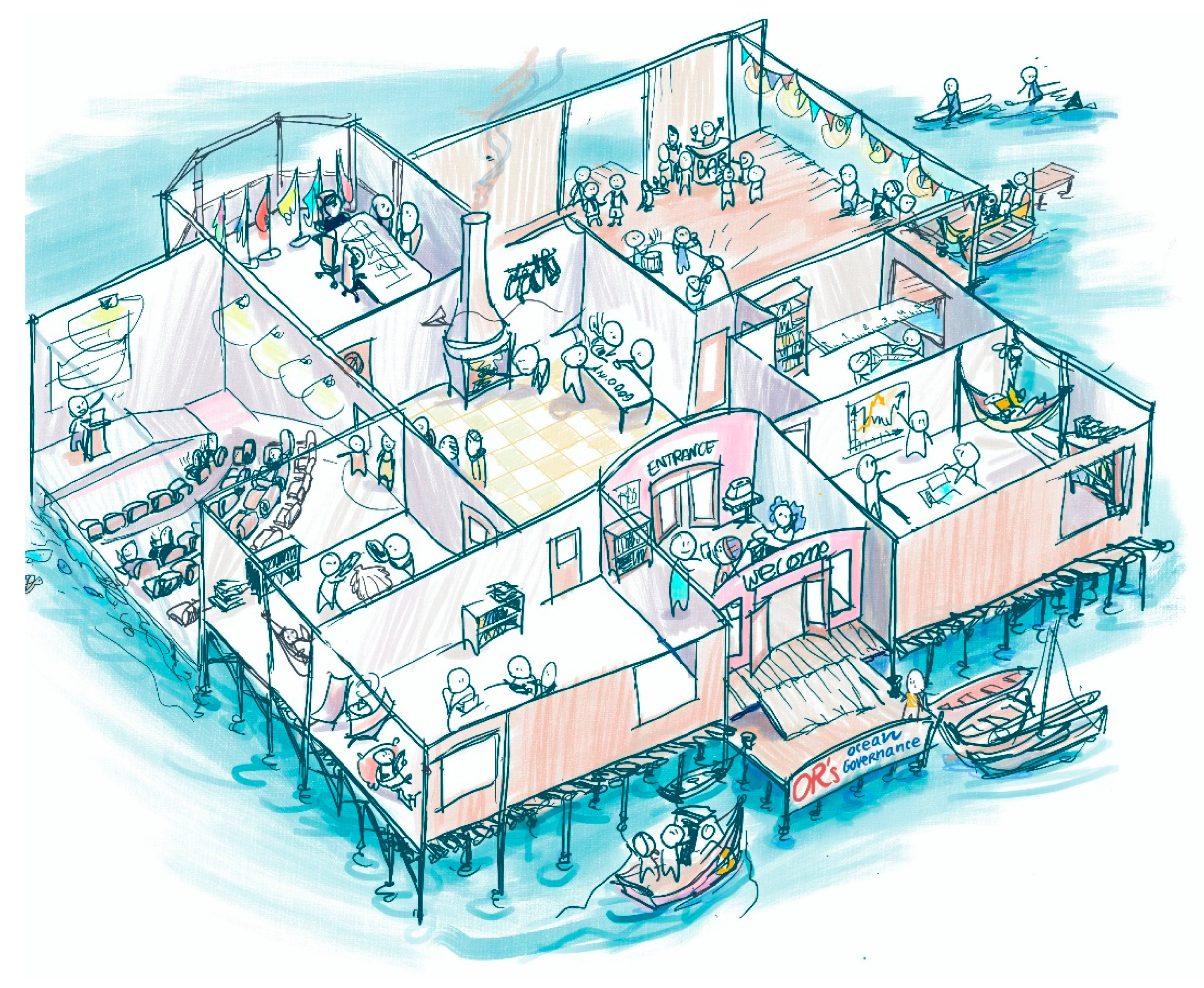

3.3. MSP-OR Platform Creation

3.3.1. Stakeholder Inclusion

3.3.2. Digital Landscape

3.4. Design and Implementation of the MSP-OR Platform

3.5. Evaluation of MSP-OR Platform

4. Recommendations for Future Research: Charting A Course for E-Sustainable Ocean Platforms

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Name | Type of Platform | Format | Topic | Who, What Entities | Frequency of Meetings/How to Create Dialogue | Ocean Governance Lens |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HELCOM | Governance platform | Website, news page, database with publications and map tool, meeting database, sign in to SharePoint (interactive platform for authorised people). Social media: Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn, Flickr | HELCOM serves as a regional platform for environmental policy making in the Baltic Sea region. Signed in 1974 by the Baltic countries and amended over time to keep up with International Maritime Law modifications | The ministerial representatives from membership countries and 8 working groups: Gear, maritime, pressure, response, state & conservation, agriculture, fish, MSP. HELCOM makes recommendations of policies which have to be implemented by the member states. Workgroups consist of representatives from each member state (Baltic state + EU) | Ministerial meetings once every 3/4 years, workgroup meetings ±5 times a year (differs per workgroup), online or in person. | HELCOM facilitates cross-border cooperation between the Baltic states, makes legally binding decisions for the management of the Baltic Sea, and works in groups with representatives from all countries. |

| OSPAR | Governance platform, advisory/ recommendation function, | Website, newsletters, OSMIS as a data and information management system, OAP as an assessments portal, publications subcategorised by topic, social media: LinkedIn, Twitter, member login (Basecamp) for communication among the working group members | OSPAR is a regional sea convention and aims to make agreements with its member states on sustainable practices in the North Atlantic Ocean. Working areas: biological diversity & ecosystems, hazardous substances & eutrophication, human activities, offshore industry, radioactive substances and cross-cutting issues with all subtopics in these areas | OSPAR has a commission and 15 contracting parties and the European Union. OSPAR makes decisions and recommendations, where the decisions are legally binding to its contracting parties, the contracting parties have to set up the measures while OSPAR sets up guidelines | Monthly meetings, meetings per thematic working group, ministerial meetings, presence at international conferences | Not so much a governing function, but more a legislative function. Member States who, if signed, have to comply with agreements. Exchange of knowledge on best techniques and practices. Common framework of monitoring practices. Collaboration from an ecosystem-based approach. |

| MSP Global forum | Learning platform, networking platform, supporting platform | Website with portals to MSP global (international guidance plan and pilot project, MSP forum, with links to past forums and documents and videos archived and MSP roadmap with all the countries MSP profiles layed out and links to evaluation documents and MSP toolkit. Social media: YouTube, Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn, News portal and event page | MSP Global aims to support governments with their MSP process to speed up and synchronise MSP projects. The forum is led by a team of MSP specialists who have worked to develop a joint roadmap and international MSP guide to support the government’s MSP processes, along with six policy briefs for governments about topics related to marine spatial planning. Exchange of knowledge and best practices. | A group of experts and a consultancy group of thematic experts aimed to support MSP planners from all levels of governments all over the world. Platform for governments and planners, as well as other people (such as students). | Six large MSP forum workshops between 2018 and 2020 and regular webinars and workshops, monthly, to present projects and work on themes. | Works towards a common framework of practices in Maritime Spatial Planning that can be implemented all over the world. Facilitates cooperation between projects and countries. By making content available in multiple languages, the knowledge can reach many people. |

| MSP EU | Learning platform, networking platform, supporting platform | Newsletters, workshops, seminars, round-the-table discussions, FAQ page, regional experts available for questions, databases of former practices and library available, links to training and funding opportunities social media: twitter | Gateway for information and communication about MSP development in the EU member states | Who? A team of MSP experts, central and regional (Sea Basins) for European MSP projects | Several meetings a year and additional activities such as thematic workshops on request, frequent newsletter | In terms of ocean governance, MSP EU is a good example of how a platform can be an extension of an implemented regulation (EU MSP-directive), targeting everyone involved in the MSP process |

| IOG Forum | Learning platform, informative platform | Website, Interactive stakeholder conferences, thematic workshops, webinars and discussions, online surveys, social media, login portal for EU(?) | The forum aims to support the framework for international governance and bring stakeholders and ocean actors together. | Stakeholders in all marine sectors in workshops | Frequently supported meetings, upcoming events, and events organised in the past are all documented. | |

| Sargasso Sea Commission | Informative platform, government platform, advising | Newsletter sign up, social media: LinkedIn, Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, Instagram. Website with archives of past meetings and workshops on important themes | Since there is no regional sea authority in the Sargasso Sea (sargassum sea more an sargassum ‘forest’ in North Atlantic ocean, with no land borders, formed by currents), the Commission works together to get international recognition for the importance of the sea and its ecosystems, work together with the fragmented jurisdictions, to forward proposals for protection and work with UNCLOS to develop better legislation for areas like this: advice and guide. | An advisory group of oceans experts’ representatives of allied states (stewardship role), work with the governments of Azores, Bahamas, Bermuda, British Virgin Islands, Canada, Cayman Islands, Dominican Republic, Monaco, UK and US. | Quarterly newsletters, yearly meetings (since corona every two months), workshops | In terms of ocean governance, the Sargasso Sea Commission is an initiative that attempts to manage an area that is beyond borders on national jurisdiction. Even though it has no binding power, it works with governments (regional and national) to play a role in international decision-making and advising international maritime law by working with experts in the field. |

| High Sea Alliance | Informative platform | Website, news portal, Youth Ambassador program with blogs, social media channels: YouTube, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram. Treaty Tracker as a portal to enable stakeholders to follow the negotiations about the high seas on a daily basis in order to increase transparency | The High Sea Alliance aims to connect NGOs to work together to create better conservation for the high seas, establish protected areas for the high seas, and facilitate access to information to increase transparency in order to inform and engage the public and decision makers | Group of ocean specialists, from marine biologists to environmental lawyers working with NGOs to speak on UN conventions as representatives of the high seas | n/a (yearly representation on UN conventions), treaty tracker updated daily | |

| Atlantic Platform (Atlantic Action Plan) | Informative platform | Website with newsletter (signup), database of past projects, teams and descriptions, events (their events and external events) on different topics, workshops and conferences. Links to social media: Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, YouTube (EUAtlantic), EU datahub as an interactive map where all the projects and initiatives can be found | Atlantic Action Plan aims to support the Atlantic Marine Strategy, a EU-mandated strategy to connect and coordinate cooperation between ocean stakeholders across the Atlantic. A team of experts assists with initiatives and accessing EU funding schemes. Promote entrepreneurship and innovation, improve accessibility and connectivity, advance regional development models. Action plan is structured in 7 goals and 4 strategic themes covering both conservation goals as well as blue growth objectives | Team of specialists to advance the workings of the EU Atlantic strategy, working with stakeholders in France, Spain, Portugal and Ireland) | Workshops and other thematic events at least once a month | |

| Ocean and Climate Platform | Collaboration platform, information platform | Website, newsletter, resource database with infographics, scientific sheets, policy recommendations, and help in understanding IPCC reports. Archives with all publications, Links to social media: Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn. On Social media, links to all ocean-related events of partner organisations. Content available in English and French. Workshops and thematic meetings | Science-polity interface where all actors in ocean issues can exchange knowledge and mobilize people from the scientific community, civil society, and policy-makers to advocate for integrating ocean issues in national and international policy-making. | Over 90 research institutes, NGOs, aquariums, private sector, French institutions and international agencies, local authorities. The organization is supported by a scientific expert committee and technical staff | Conferences and thematic meetings, communication campaigns and production of informational tools, frequency not available. Endorsing monthly events of partners in OCP network | OCP aims to be a large network of all layers of society and spread their message to everyone in order to mobilize people and influence governance. Bottom up approach. They interact through events from NGO’s, art shows, exhibitions, conferences and workshops and present information from governmental institutions in information sheets to make it accessible for everyone. |

| EU Marine Board | Scientific platform | Website, newsletter, projects, meeting documents (restricted page), webinars, representation in other forums, work documents, research publications and outputs archived, social media: Instagram, Facebook, twitter, YouTube (with recordings of all webinars) | The Forum aims to facilitate action at the regional level, thereby supporting the implementation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, in particular SDG 14, and build a bridge to a post-2020 pathway for ocean health. EU Marine Board aims to connect scientific research to policy and make recommendations based on scientific research to national governments as well as European Institutions. Bring together scientific stakeholders and identify common challenges | 35 research institutes from 18 European countries, all represented in the board and working together with thousands of scientists to create science policy advice | Bi-annual meetings, monthly webinars to discuss EMB’s publications | EBM is more design to support ocean governance, by providing scientific support, and identify priority issues for governance to work on. In the scientific based policy making, research is vital and EBM is a tool to collect the ongoing research and inform the decision makers |

References

- Zacharias, M. An introduction to governance and international law of the oceans. In Marine Policy; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, J.; Trigal, L.; Sposito, E. (Eds.) Dicionário de Geografia Aplicada: Terminologia da Análise, do Planeamento e da Gestão do Território; Porto Editora: Porto, Portugal, 2016; p. 568. Available online: https://www.wook.pt/livro/dicionario-de-geografia-aplicada/16807109?srsltid=AfmBOoqpuIweR02ZhCLyutP_AVjBF00BE_ObeFRTXYyjE7SIz6i8xPjQ (accessed on 3 February 2023).

- UN. The Ocean and the Sustainable Development Goals Under the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development—A Technical Abstract of The First Global Integrated Marine Assessment. 2017. Available online: https://www.un.org/depts/los/global_reporting/8th_adhoc_2017/Technical_Abstract_on_the_Ocean_and_the_Sustainable_Development_Goals_under_the_2030_Agenda_for_Susutainable_Development.pdf (accessed on 25 September 2021).

- Zaucha, J. Sea basin maritime spatial planning: A case study of the Baltic Sea region and Poland. Mar. Policy 2014, 50, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carneiro, C.; Thomas, H.; Olsen, S.; Benzaken, D.; Fletcher, S.; Stanwell-Smith, D.; Roldan, S.M. Cross-border cooperation in maritime spatial planning. In Final Report: Study on International Best Practices for Cross-Border MSP; Publications of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2017; p. 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partelow, S.; Hadjimichael, M.; Hornidge, A.-K. Ocean Governance; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claudet, J.; Bopp, L.; Cheung, W.W.L.; Devillers, R.; Escobar-Briones, E.; Haugan, P.; Heymans, J.J.; Masson-Delmotte, V.; Matz-Lück, N.; Miloslavich, P.; et al. A roadmap for using the UN decade of ocean science for sustainable development in support of science, policy, and action. One Earth 2020, 2, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koski, C.; Rönneberg, M.; Kettunen, P.; Armoškaitė, A.; Strake, S.; Oksanen, J. User Experiences of Using a Spatial Analysis Tool in Collaborative GIS for Maritime Spatial Planning. Trans. GIS 2021, 25, 1809–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majidi Nezhad, M.; Neshat, M.; Piras, G.; Astiaso Garcia, D.; Sylaios, G. Marine Online Platforms of Services to Public End-Users—The Innovation of the ODYSSEA Project. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calado, H.; Moreira, M.; Santos, N.; Melo, N.; Cipriano, F.D. 2.3—Report on Main Discussed Issues on the Platform. In MSP-OR Project; Grant Agreement No. GA 101035822—MSP-OR—EMFF-MSP-2020; European Climate, Infrastructure and Environment Executive Agency: Brussels, Belgium, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ansell, C.; Alison, G. Collaborative Platforms as a Governance Strategy. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2018, 28, 16–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnevie, I.M.; Hansen, H.S.; Schrøder, L.; Rönneberg, M.; Kettunen, P.; Koski, C.; Oksanen, J. Engaging Stakeholders in Marine Spatial Planning for Collaborative Scoring of Conflicts and Synergies within a Spatial Tool Environment. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2023, 233, 106449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerson, K.; Nabatchi, T.; Balogh, S. An Integrative Framework for Collaborative Governance. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2012, 22, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaymer, C.F.; Stadel, A.V.; Ban, N.C.; Cárcamo, P.F.; Ierna, J.; Lieberknecht, L.M. Merging Top-down and Bottom-up Approaches in Marine Protected Areas Planning: Experiences from around the Globe. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 2014, 24, 128–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, D.; Calado, H.; García-Sanabria, J. A Proposal for Engagement in MPAs in Areas beyond National Jurisdiction: The Case of Macaronesia. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 854, 158711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, K.; Alam, A. Planning for Blue Economy: Prospects of Maritime Spatial Planning in Bangladesh. AIUB J. Sci. Eng. 2018, 17, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wever, L.; Glaser, M.; Gorris, P.; Ferrol-Schulte, D. Decentralisation and Participation in Integrated Coastal Management: Policy Lessons from Brazil and Indonesia. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2012, 66, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasheed, A.; Abdulla, A. Engaging Stakeholders in Marine Governance: Challenges and Opportunities. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2020, 184, 104861. [Google Scholar]

- Von Thenen, M.; Armoškaitė, A.; Cordero-Penín, V.; García-Morales, S.; Gottschalk, J.B.; Gutierrez, D.; Ripken, M.; Thoya, P.; Schiele, K.S. The Future of Marine Spatial Planning: Perspectives from Early Career Researchers. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, N.M.; Coolsaet, B.; Sterling, E.J.; Loveridge, R.; Gross-Camp, N.D.; Wongbusarakum, S.; Sangha, K.K.; Scherl, L.M.; Phan, H.P.; Zafra-Calvo, N.; et al. The Role of Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities in Effective and Equitable Conservation. Ecol. Soc. 2021, 26, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiand, L.; Unger, S.; Rochette, J.; Müller, A.; Neumann, B. Advancing Ocean Governance in Marine Regions through Stakeholder Dialogue Processes. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO-IOC. MSPglobal International Guide on Marine/Maritime Spatial Planning; IOC Manuals and Guides No. 89; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph, T.B.; Ruckelshaus, M.; Swilling, M.; Allison, E.H.; Österblom, H.; Gelcich, S.; Mbatha, P. A Transition to Sustainable Ocean Governance. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pınarbaşı, K.; Galparsoro, I.; Borja, Á.; Stelzenmüller, V.; Ehler, C.N.; Gimpel, A. Decision Support Tools in Marine Spatial Planning: Present Applications, Gaps, and Future Perspectives. Mar. Policy 2017, 83, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanning, L.; Mahon, R. Governance of the Global Ocean Commons: Hopelessly Fragmented or Fixable? Coast. Manag. 2020, 48, 527–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, N.J.; Cisneros-Montemayor, A.M.; Blythe, J.; Silver, J.J.; Singh, G.; Andrews, N.; Calò, A.; Christie, P.; Di Franco, A.; Finkbeiner, E.M.; et al. Towards a Sustainable and Equitable Blue Economy. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 991–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassen, M. Promoting Public Cooperation in Government: Key Drivers, Regulation, and Barriers of the E-Collaboration Movement in Kazakhstan. Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2018, 85, 743–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinley, E.; Crowe, P.R.; Stori, F.; Ballinger, R.; Brew, T.C.; Blacklaw-Jones, L.; Foley, K. ‘Going Digital’—Lessons for Future Coastal Community Engagement and Climate Change Adaptation. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2021, 208, 105629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EPBRS. Concept Note: Network of Knowledge for Biodiversity Governance; EPBRS: Brussels, Belgium, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ribalaygua, C.; García, F.; Sánchez, H.G. European Island Outermost Regions and Climate Change Adaptation: A New Role for Regional Planning. Isl. Stud. J. 2019, 14, 21–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergílio, M.H.; Calado, H.M.G.P. Spatial Planning in Small Islands: The Need to Discuss the Concept of Ecological Structure. Plan. Pract. Res. 2016, 31, 452–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO-IOC. MSPglobal Policy Brief: Ocean Governance and Marine Spatial Planning; IOC Policy Brief; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- García-Sanabria, J.; García-Onetti, J.; Pallero Flores, C.; Cordero Penín, V.; Andrés García, M.; Arcila Garrido, M. MSP Governance Analysis of the European Macaronesia. Deliverable D.6.5 under the WP6 of MarSP. In Macaronesian Maritime Spatial Planning Project; GA No. EASME/EMFF/2016/1.2.1.6/03SI2.763106; European Climate, Infrastructure and Environment Executive Agency: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez, D.; Van Toor, F.; Calado, H.; Campillos, M.; Nuñez, C.C.; Santos, N.; Silva, A. Report on Needs, Barriers, and Enablers for MSP and Capacity Building (D2.1). In MSP-OR Project; GA No. 101035822; European Climate, Infrastructure and Environment Executive Agency: Brussels, Belgium, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ehler, C.; Douvere, F. Marine Spatial Planning: A Step-by-Step Approach Toward Ecosystem-Based Management; IOC Manual & Guide No. 53; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Diederichsen, S.D.; Weiss, C.V.C.; Lukic, I.; Rebours, C.; Walsh, J.P.; McCann, J.; Juell-Skielse, E.; Gröndahl, F.; Scherer, M.E.G. Assessment Framework for Successful Development of Viable Ocean Multi-Use Systems: A Case Study from the Pirajubaé Marine Extractive Reserve, Brazil. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2025, 266, 107689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Barriers | Enablers |

|---|---|

| Logging in to a platform takes too much time. | Push notifications (for example, automatic messages sent via email to the users when documents were submitted for review or consultation) to react with platform use. |

| Expensive to keep a platform going and moderate interaction and content. | Create a network/community to make interaction and collaboration easier --> effective collaboration. |

| Data protection laws can make platform transparency challenging. | Platform as moderator, bringing together data from different working groups. |

| Collaboration strands on checking the compatibility of the initiative rather than a collaborative project. Sometimes, published knowledge can also prevent interaction. | Non-governmental input can be generated through a platform, by presenting documents and making them accessible. |

| Links, websites, and videos expire after a while. To maintain content, move it to a more permanent host. | Platform as a knowledge centre, publish best practices. Tools and guidelines for future projects within the region and outside of the region. |

| Multimedia and innovative solutions can also exclude certain groups and areas (for example, inaccessibility due to a lack of internet). | An interactive PDF presents data in a concentrated but readable way. Other formats of interaction do not always have to be new (e.g., YouTube). |

| Mailing lists can be useful during the implementation phase to highlight new inputs; after that, the tool becomes less useful. | Multiple languages can extend reach and generate more input. |

| Usually, government platforms are more about information rather than communication. | Incorporate different levels of information, aimed at different types of users. |

| When introducing interactive aspects, consider the vetting process to avoid spam and robot accounts. | Several projects seek interactive aspects. The implementation phase requires input from civil society and other non-governmental actors. |

| User engagement is needed before it can be an effective tool. | Online platforms can include hidden groups, where certain content stays private, and other content can be public. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gutierrez, D.; Calado, H.; Toor, F.v.; Moreira, M.; Paramio, M.L.; Martins, F.; Santos, N.; Melo, N.; Newton, A. Empowering Maritime Spatial Planning and Marine Conservation Efforts Through Digital Engagement: The Role of Online Platforms. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6371. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146371

Gutierrez D, Calado H, Toor Fv, Moreira M, Paramio ML, Martins F, Santos N, Melo N, Newton A. Empowering Maritime Spatial Planning and Marine Conservation Efforts Through Digital Engagement: The Role of Online Platforms. Sustainability. 2025; 17(14):6371. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146371

Chicago/Turabian StyleGutierrez, Débora, Helena Calado, Femke van Toor, Mariana Moreira, Maria Luz Paramio, Francisco Martins, Natali Santos, Neuza Melo, and Alice Newton. 2025. "Empowering Maritime Spatial Planning and Marine Conservation Efforts Through Digital Engagement: The Role of Online Platforms" Sustainability 17, no. 14: 6371. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146371

APA StyleGutierrez, D., Calado, H., Toor, F. v., Moreira, M., Paramio, M. L., Martins, F., Santos, N., Melo, N., & Newton, A. (2025). Empowering Maritime Spatial Planning and Marine Conservation Efforts Through Digital Engagement: The Role of Online Platforms. Sustainability, 17(14), 6371. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146371