The Impact of Green Mergers and Acquisitions on the Market Power of Heavily Polluting Enterprises

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

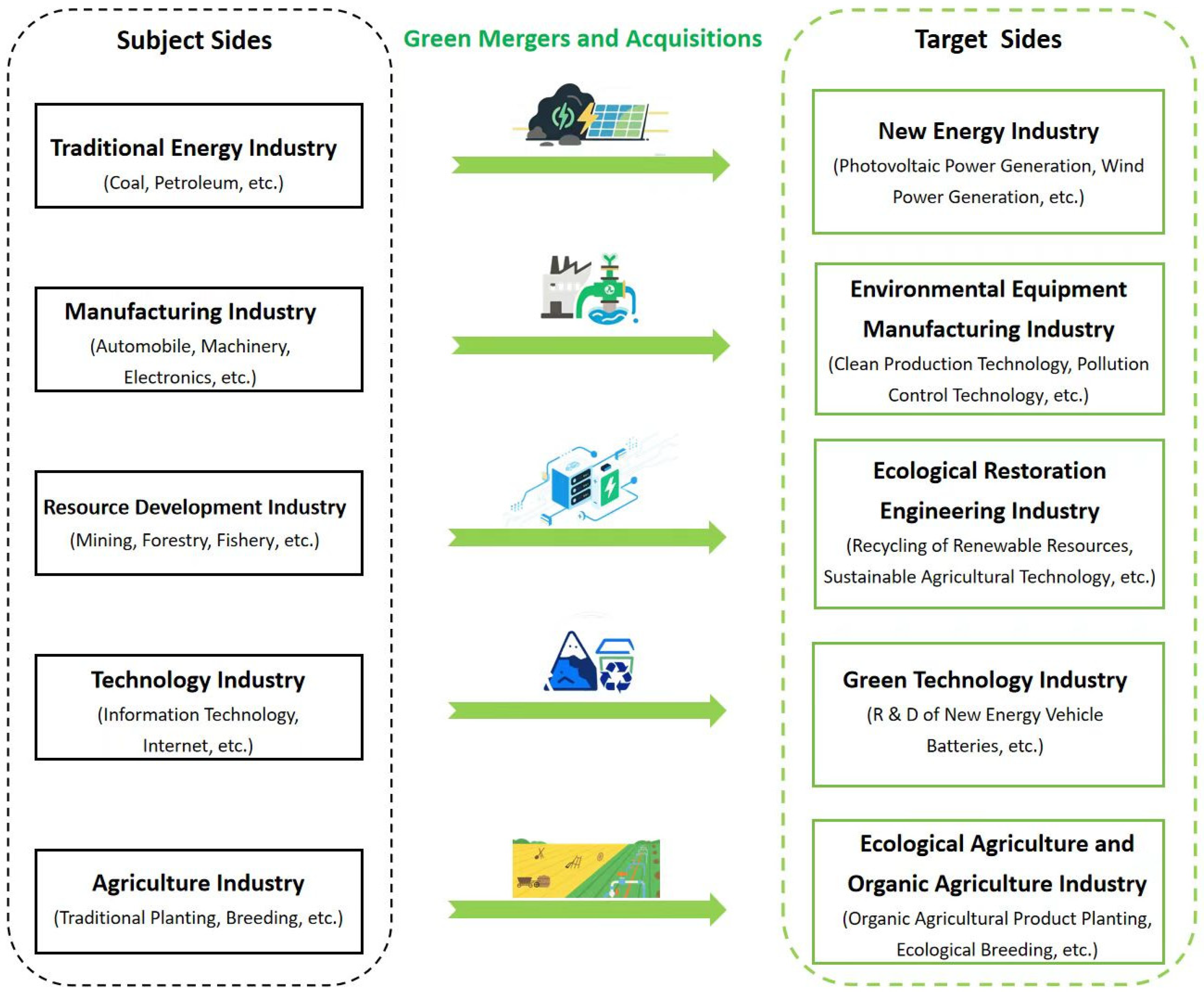

2.1. Green Mergers and Acquisitions

2.2. Mergers and Acquisitions and Enterprise Market Power

2.3. Research Gap

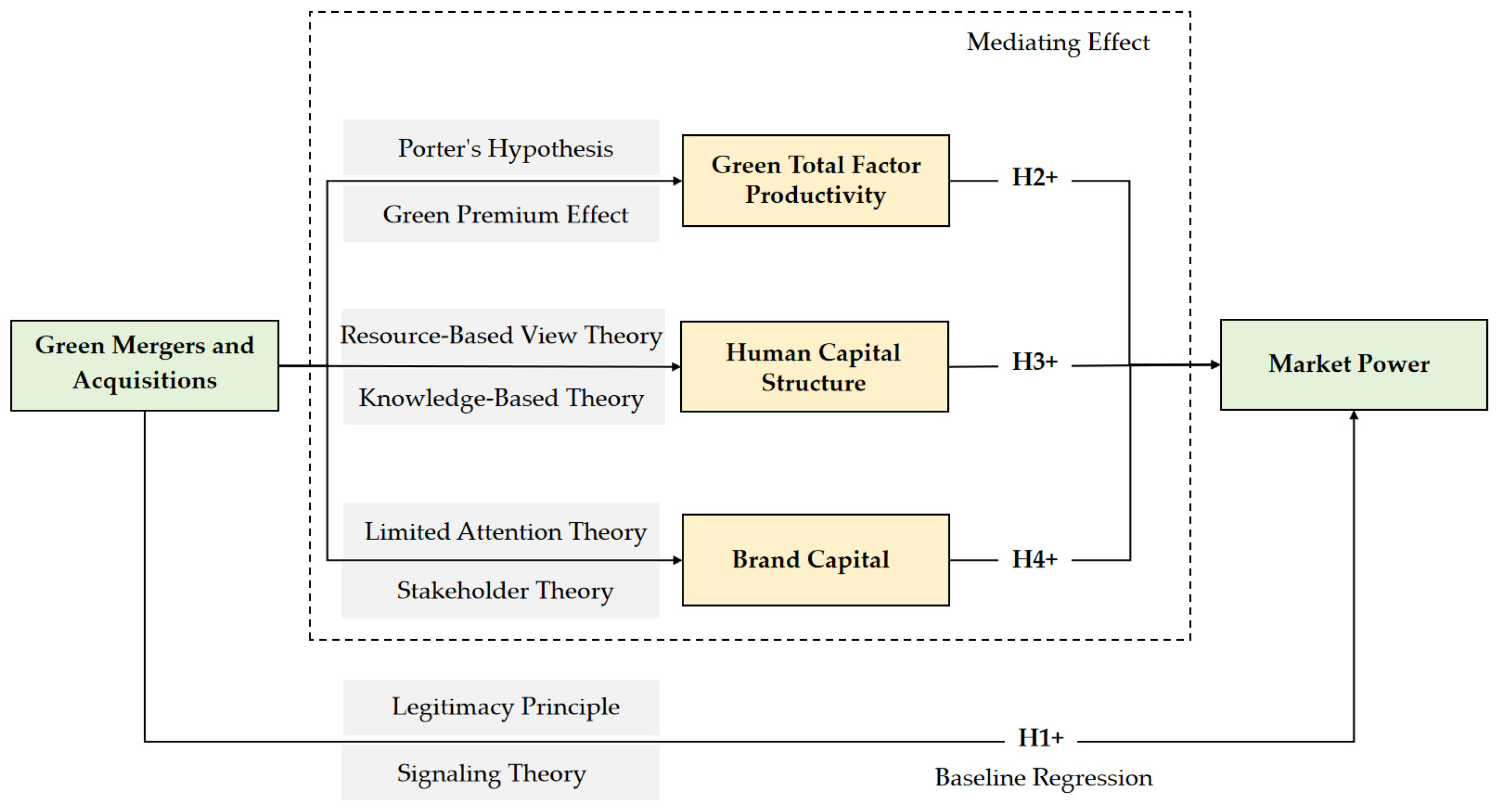

3. Theoretical Analysis and Research Hypotheses

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Data Sources

4.2. Variable Selection

4.2.1. Explained Variable

4.2.2. Explanatory Variable

4.2.3. Mediating Variables

4.2.4. Control Variables

4.3. Dodel Design

4.3.1. Benchmark Regression Model

4.3.2. Mediating Effect Model

5. Empirical Analysis

5.1. Descriptive Statistics Result

5.2. The Baseline Regression Result

5.3. Robustness Test Result

5.3.1. Empirical Testing with Matched Samples

5.3.2. Other Robustness Tests

5.3.3. Endogeneity Test

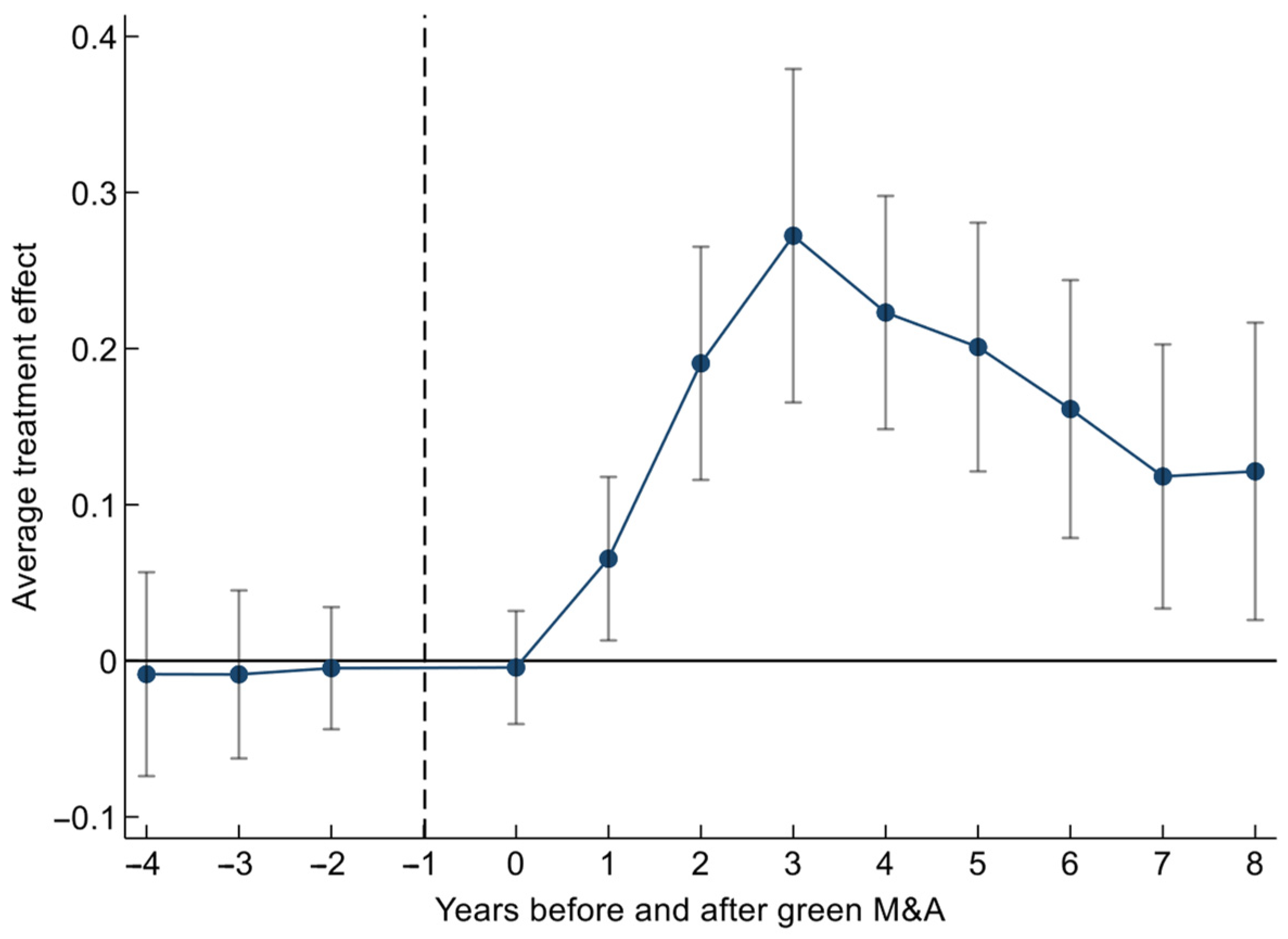

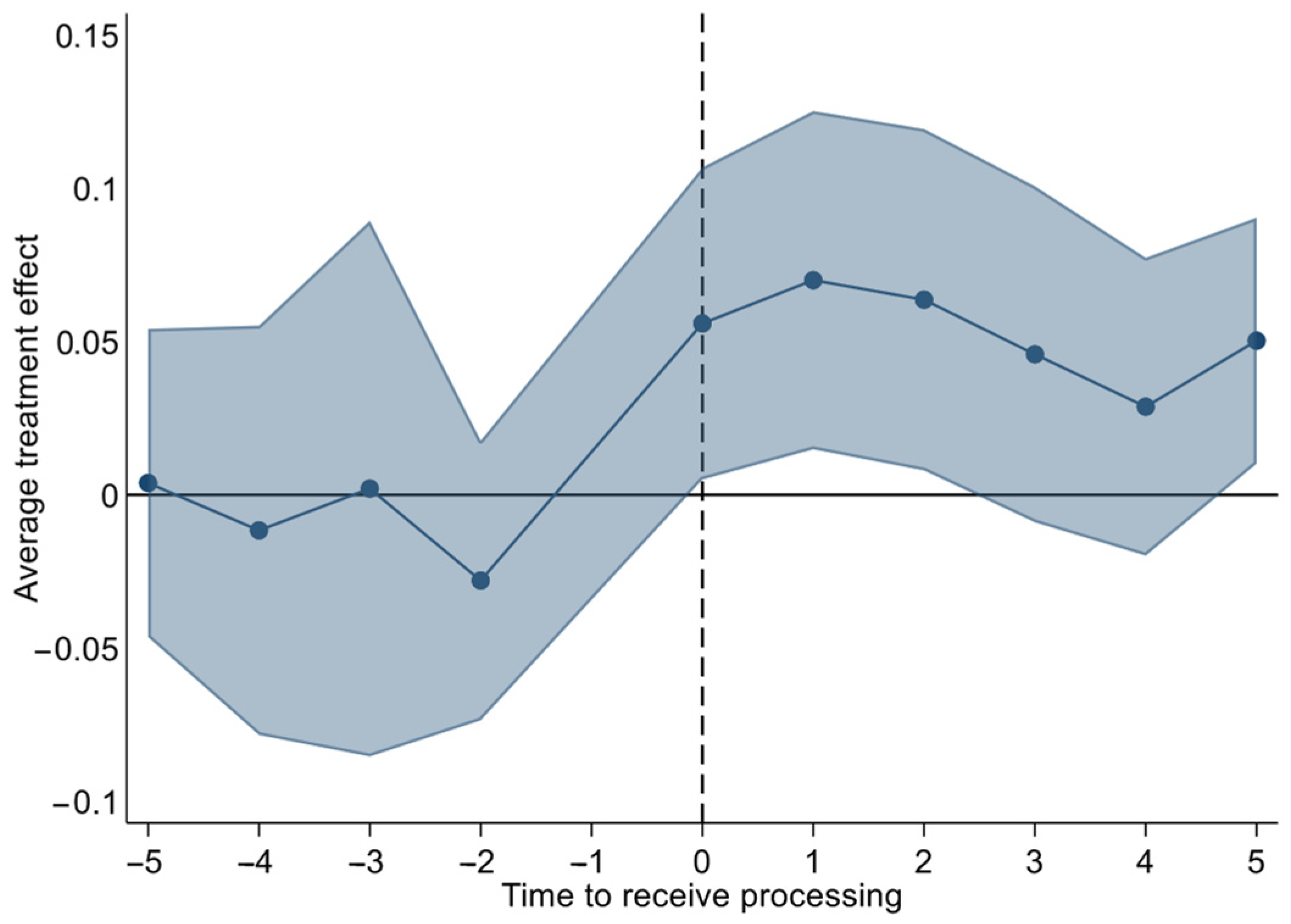

5.3.4. Parallel Trend Test

5.3.5. Counterfactual Tests

5.3.6. Placebo Test

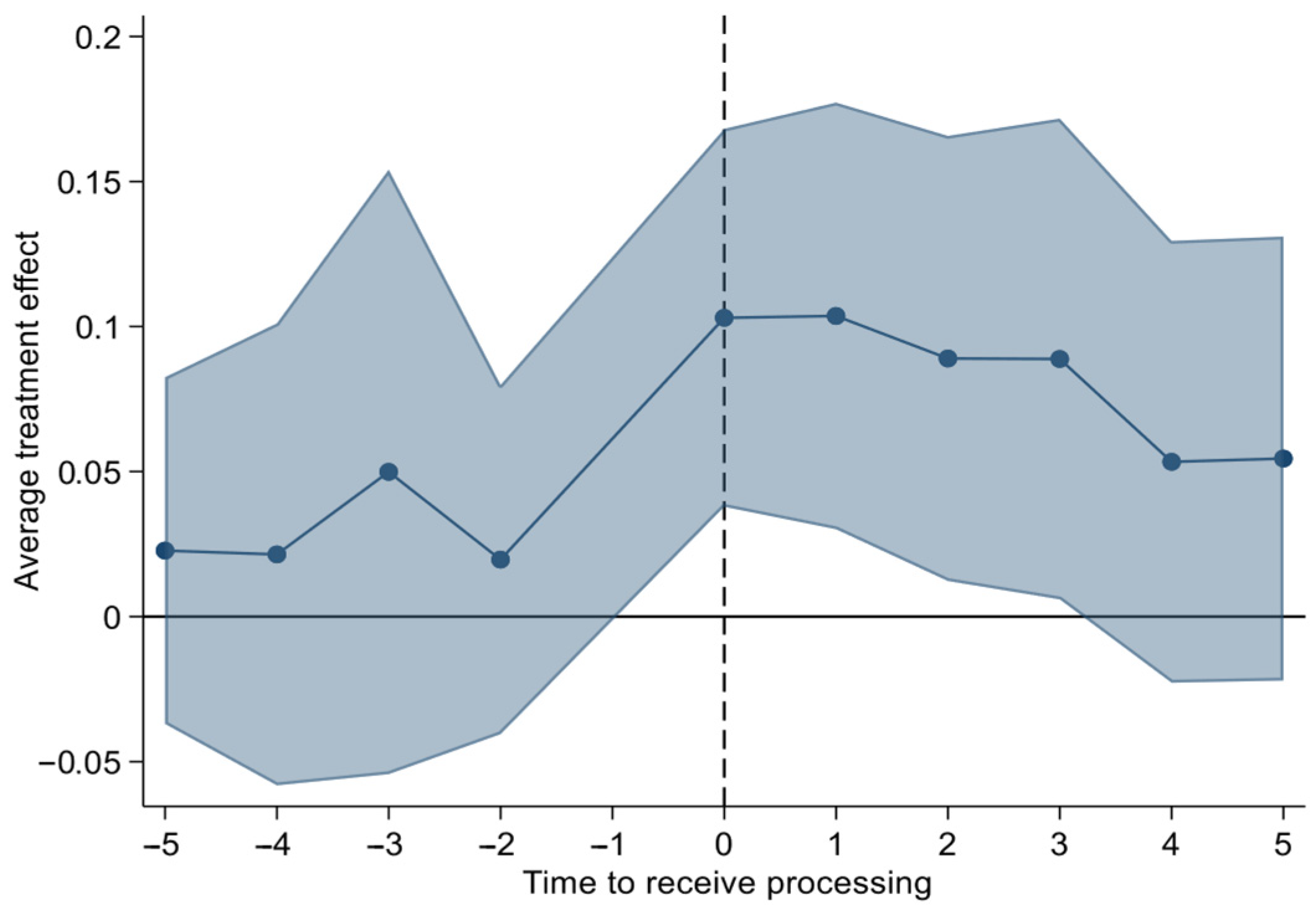

5.3.7. Multi-Time DID Heterogeneous Treatment Effects

5.4. Mediating Effect Test

5.4.1. Mediating Effect Test of Green TFP

5.4.2. Mediating Effect Test of Human Capital

5.4.3. Mediating Effect Test of Brand Capital

5.5. Heterogeneity Test

5.5.1. Heterogeneity of Merger and Acquisition Methods

5.5.2. Enterprise Heterogeneity: State-Owned Enterprises vs. Non-State-Owned Enterprises

5.5.3. Enterprise Heterogeneity: Growing, Mature, and Declining Enterprises

6. Discussion and Conclusions

6.1. Discussion

6.2. Conclusions

6.3. Recommendations

6.4. Limitations and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, C.Q.; Cheng, L.X. Study on general industrial solid waste and carbon reduction in China: Coupling coordination model, life cycle assessment and environmental safety control. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2024, 39, 101557. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, J.; Zhou, M.; Yi, M.; Fu, S. Unveiling the impact of digital industrialization on synergistic governance of pollution and carbon reduction in China: A geospatial perspective. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2024, 31, 36454–36473. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Wu, K.; Liang, X. Does low-carbon pilot policy promote corporate green total factor productivity? Econ. Anal. Policy 2024, 84, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Griffith, R.; Miller, H. Taxable corporate profits. Fisc. Stud. 2014, 35, 535–557. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Wang, H. Factor market distortion, technological innovation, and environmental pollution. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2022, 29, 87692–87705. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, G.; Ji, G.; Tan, K.H. Impact of regulatory intervention and consumer environmental concern on product introduction. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2020, 230, 107898. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Zhao, C.; Ning, J.; Yin, S.; Zhang, D. Does ecological accountability restrain the financialization of heavily polluting enterprises? Evidence from China. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 12, 1400725. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, N.; Zhou, L.; Xu, L.; Xiang, S. Symbolic or substantive CSR: Effect of green mergers and acquisitions premium on firm value in China. Chin. Manag. Stud. 2024, 18, 628–655. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B.; Xu, L.; McIver, R.; Wu, Q.; Pan, A. Green M&A, legitimacy and risk-taking: Evidence from China’s heavy polluters. Account. Financ. 2020, 60, 97–127. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K.; Zhang, X. The effect of media coverage on disciplining firms’ pollution behaviors: Evidence from Chinese heavy polluting listed companies. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 280, 123035. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, X.; Chen, D.; Zhou, Y.W.; Lin, Q. Horizontal mergers in low carbon manufacturing. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2022, 297, 359–368. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, X.; Li, S.; Luo, P.; Li, Z. Green mergers and acquisitions and green innovation: An empirical study on heavily polluting enterprises. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 48937–48952. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Sun, Z.; Zhou, Y. Green merger and acquisition and green technology innovation: Stimulating quantity or quality? Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2023, 103, 107265. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, W.; Yuan, T. Green innovation of Chinese industrial enterprises to achieve the ‘dual carbon’goal–based on the perspective of green M&A. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2023, 30, 1809–1813. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Wang, W.; Gao, H.; Zhu, H. The Impact of Green Mergers and Acquisitions on Corporate Environmental Performance: Evidence from China’s Heavy-Polluting Industries. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3796. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Sun, Z.; Sheng, A.; Zhang, L.; Kan, Y. Can green technology mergers and acquisitions enhance sustainable development? Evidence from ESG ratings. Susuain. Dev. 2024, 32, 6072–6087. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Sun, Z.; Sun, M.; Zhou, Y. The effective path of green transformation of heavily polluting enterprises promoted by green merger and acquisition—Qualitative comparative analysis based on fuzzy sets. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 63277–63293. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, J.; Li, H.; Wang, G. The impact of green mergers and acquisitions on illegal pollution discharge of heavy polluting firms: Mechanism, heterogeneity and spillover effects. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 340, 117973. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, J. Can the green merger and acquisition strategy improve the environmental protection investment of listed company? Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2021, 86, 106470. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Z.; Sun, X.; Wang, W.; Wang, W. Source reduction strategy or end-of-pipe solution? The impact of green merger and acquisition on environmental investment strategy of Chinese heavily polluting enterprises. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 413, 137530. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, J. Green merger and acquisition and export expansion: Evidence from China’s polluting enterprises. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 30, 204–217. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, P.; Huang, Q. Green mergers and acquisitions and corporate environmental responsibility: Substantial transformation or strategic arbitrage? Econ. Anal. Policy 2024, 83, 1023–1040. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Yuan, B.L.; Zheng, J.J. Strategic Response or Substantive Response? The Effect of China’s Carbon Emissions Trading Policy on Enterprise Green Innovation. Nankai Bus. Rev. 2024, 27, 129–140. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Sun, Z.Y.; Sheng, A.Q. Substantial Transformation or Strategic Response? The Impact of Green Mergers and Acquisitions on Enterprise Green Technology Innovation. Sci. Technol. Prog. Policy 2023, 40, 68–78. [Google Scholar]

- Nocke, V.; Yeaple, S. An assignment theory of foreign direct investment. Rev. Econ. Stud. 2008, 75, 529–557. [Google Scholar]

- Fred, W.J. Takeovers, Restructuring and Corporate Governance; Pearson Education India: Noida, India, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Neary, J.P. Cross-border mergers as instruments of comparative advantage. Rev. Econ. Stud. 2007, 74, 1229–1257. [Google Scholar]

- Moeller, S.B.; Schlingemann, F.P.; Stulz, R.M. Wealth destruction on a massive scale? A study of acquiring-firm returns in the recent merger wave. J. Financ. 2005, 60, 757–782. [Google Scholar]

- Lauterbach, B.; Mugerman, Y.; Shemesh, J. Prospect theory in M&A: Do historical purchase prices affect merger offer premiums and announcement returns? J. Behav. Exp. Financ. 2024, 42, 100931. [Google Scholar]

- Stiebale, J.; Szücs, F. Mergers and market power: Evidence from rivals’ responses in European markets. Rand J. Econ. 2022, 53, 678–702. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, X.; Yang, H.; Yang, P. The Impact of Cross-Border Mergers and Acquisitions on Corporate Organisational Resilience: Insights from Dynamic Capability Theory. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.D.; Fang, S.H.; Jiang, D.C. Market Performance in Digital Transformation: Can Digital M&As Enhance Manufacturing Firm’s Market Power? J. Quant. Technol. 2022, 39, 90–110. [Google Scholar]

- Pang, S.; Hua, G.; Liu, Y. Legitimacy and Opportunism: Examining Climate Risk and Green Mergers and Acquisitions in Polluting Firms. Bus. Ethics 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, X. Green mergers and acquisitions in corporate low-carbon transition: A driving mechanism based on dual external pressures. Rev. Int. Econ. 2025, 98, 103865. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Z.; Sun, X.; Wang, L.; Wang, W. Substantive transformation or strategic response? The impact of a negative social responsibility performance gap on green merger and acquisition of heavily polluting firms. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2025, 68, 1238–1262. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, W. Environmental information disclosure, credit scale and credit cost. Acad. J. Bus. Manag. 2020, 2, 37–51. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Zhao, H. A configuration analysis of the driving path of corporate physical investments: Necessary condition analysis and qualitative comparative analysis based on fuzzy sets. Manag. Decis. Econ. 2025, 46, 681–697. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, S.L.; Dowell, G. Invited editorial: A natural-resource-based view of the firm: Fifteen years after. J. Manag. 2010, 37, 1464–1479. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, Y.; Xie, W.; Qian, X.; Lv, J. Peer effect in mergers and acquisitions for green innovation. J. Innov. Knowl. 2025, 10, 100734. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, S.L.; Ahuja, G. Does it pay to Be green? An empirical examination of the relationship between emission reduction and firm performance. Bus. Strategy Environ. 1996, 5, 30–37. [Google Scholar]

- Jovanovic, B.; Rousseau, P.L. Mergeras Reallocation. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2008, 90, 765–776. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Z.; Li, Y.; Shao, X. Strategic green marketing and cross-border merger and acquisition completion: The role of corporate social responsibility and green patent development. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 343, 130961. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B.; Gong, S. How does digital transformation drive green technology M&A under the carbon cap and trade policy? Technol. Soc. 2025, 81, 102868. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.; Sun, L. Basin ecological compensation and urban green total factor productivity: Evidence from typical trans-provincial river basins in China. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2025, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemczyk, J.; Sus, A.; Borowski, K.; Jasiński, B.; Jasińska, K. The dominant motives of mergers and acquisitions in the energy sector in Western Europe from the perspective of green economy. Energies 2022, 15, 1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Chi, Y. Path selection for enterprises’ green transition: Green innovation and green mergers and acquisitions. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 412, 137397. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, T.; Kumar, N. How do green acquirers select targets? Value of green innovation in takeovers. Br. J. Manag. 2025, 36, 1303–1325. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, H.Y.; Wang, J.H.; Li, M.X. Does the Environmental Credit Evaluation Promote the Green Total Factor Productivity of Enterprises? J. Audit. Econ. 2024, 39, 96–106. [Google Scholar]

- Gugler, K.; Mueller, D.C.; Yurtoglu, B.B.; Zulehner, C. The effects of mergers: An international comparison. Int. J. Ind. Organ. 2003, 21, 625–653. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, Y.; Tarba, S.Y. Human resource practices and performance of mergers and acquisitions in Israel. Hum. Resour. Manag. Res. 2010, 20, 203–211. [Google Scholar]

- Saa-Perez, P.D.; Garcia-Falcon, J.M. A resource-based view of human resource management and organizational capabilities development. Int. J. Hum. Resourc. Manag. 2002, 13, 123–140. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Q.; Shang, Y. The Green Innovation Effect of Green Mergers and Acquisitions: Strategic Fitting or Substantial Transformation. J. Financ. Dev. Res. 2023, 6, 36–46. [Google Scholar]

- Makri, M.; Hitt, M.A.; Lane, P.J. Complementary technologies, knowledge relatedness, and invention outcomes in high technology mergers and acquisitions. Strateg. Manag. J. 2010, 31, 602–628. [Google Scholar]

- Bronnenberg, B.J.; Dubé, J.P. The formation of consumer brand preferences. Annu. Rev. Econom. 2017, 9, 353–382. [Google Scholar]

- Bahadir, S.C.; Bharadwaj, S.G.; Srivastava, R.K. Financial value of brands in mergers and acquisitions: Is value in the eye of the beholder? J. Mark. 2008, 72, 49–64. [Google Scholar]

- Meyvis, T.; Janiszewski, C. When are broader brands stronger brands? An accessibility perspective on the success of brand extensions. J. Consum. Res. 2004, 31, 346–357. [Google Scholar]

- Andrade, G.; Mitchell, M.; Stafford, E. New evidence and perspectives on mergers. J. Econ. Perspect. 2001, 15, 103–120. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, F.X.; Shen, Y.Y.; Xia, X.X. The spillover effect of advertising on the capital market: Evidence from financial constraints. J. Corp. Financ. 2024, 84, 102529. [Google Scholar]

- Junni, P.; Sarala, R.M.; Tarba, S.Y.; Weber, Y. The role of strategic agility in acquisitions. Br. J. Manag. 2015, 26, 596–616. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, A.L.; Liu, X.; Qiu, J.L. Can Green M&A of Heavy Polluting Enterprises Achieve Substantial Transformation under the Pressure of Media. China Ind. Econ. 2019, 2, 174–192. [Google Scholar]

- De Loecker, J.; Warzynski, F. Markups and Firm-Level Export Status. Am. Econ. Rev. 2012, 102, 2437–2471. [Google Scholar]

- Ackerberg, D.A.; Caves, K.; Frazer, G. Identification Properties of Recent Production Function Estimators. Econometrica 2015, 83, 2411–2451. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.N.; Fei, J.H. Measurement, difference sources and causes of green production efficiency in heavily polluting enterprises. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2021, 31, 102–109. [Google Scholar]

- Belo, F.; Lin, X.J.; Vitorino, M.A. Brand capital and firm value. Rev. Econ. Dyn. 2019, 17, 150–169. [Google Scholar]

- Corrado, C.; Hulten, C.; Sichel, D. Measuring Capital and Technology: An Expanded Framework Measuring Capital in the New Economy; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hasan, M.M.; Taylor, G. Brand capital and credit ratings. Eur. J. Financ. 2023, 29, 228–254. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, T. Mediating Effects and Moderating Effects in Causal Inference. Chin. Ind. Econ. 2022, 5, 100–120. [Google Scholar]

- McMullin, J.L.; Schonberger, B. Entropy-balanced accruals. Rev. Account. Studs. 2020, 25, 84–119. [Google Scholar]

- Spierdijka, L.; Zaourasa, M. Measuring banks’ market power in the presence of economies of scale: A scale-corrected Lerner index. J. Bank. Financ. 2018, 87, 40–48. [Google Scholar]

- Wooldridge, J.M. Econometric Analysis of Cross Section and Panel Data; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Hshieh, S.; Zhang, F. Hiring High-Skilled Labor Through Mergers and Acquisitions. J. Financ. Quant. Anal. 2024, 59, 2762–2798. [Google Scholar]

- Shiljas, K.; Kumar, D. The interplay of cash flow uncertainty and firm life cycle on sustainability disclosure. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2024, 33, 8471–8492. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, G.H. How Did Merger and Acquisitions Boost the Market Power—Evidence from Chinese Firms. China Ind. Econ. 2021, 5, 170–188. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y. Mixed Ownership Mergers and Acquisitions and Innovation-Driven Development: A Longitudinal Case Study of Guangdong Provincial State-Owned Enterprise “Hanlan Environment” during 2001–2015. J. Manag. World. 2016, 8, 150–163. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, Y. Evaluation analysis on industrial green total factor productivity and energy transition policy in resource-based region. Energy Environ. 2022, 3, 419–434. [Google Scholar]

- Chiarini, A.; Bag, S. Using green human resource management practices to achieve green performance: Evidence from Italian manufacturing context. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2024, 33, 4694–4707. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, Y.; Ding, X.; Jiang, L. Corporate environmental pictures information disclosure and investor market reaction: A new perspective from large-scale pictures feature mining. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 437, 140616. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Implication | Measurement Mode |

|---|---|---|

| MKP | Market power | Calculated by the translog function |

| GMA | Green mergers and acquisitions | Content analysis method |

| Gtfp | Green total factor productivity | Super-efficiency SBM model |

| Hum | Human capital structure | Number of employees of Shuobo/total number of employees |

| Bc | Brand capital | Perpetual inventory method |

| Size | Size of enterprise | The logarithm of total assets is taken |

| Lev | Asset–liability ratio | Total liabilities/total assets |

| TobinQ | Tobin’s Q value | Market value/total assets |

| Board | Size of directors | The logarithm of the number of directors is taken |

| Dual | Dual-career path | The chairman and the general manager are the same person 1, otherwise 0 |

| Top 1 | Shareholding proportion of the largest shareholder | Number of shares held by the largest shareholder/total number of shares |

| Listage | Years on the market | The logarithm of the difference between the current year and the listing year is taken |

| Variable | Observations | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MKP | 6487 | 1.235 | 0.427 | 0.723 | 3.186 |

| GMA | 6487 | 0.186 | 0.271 | 0 | 1 |

| Gtfp | 6487 | 1.011 | 0.038 | 0.664 | 1.392 |

| Hum | 6487 | 0.187 | 0.288 | 0 | 0.261 |

| Bc | 6487 | 16.655 | 2.766 | 7.755 | 21.149 |

| Size | 6487 | 22.565 | 1.380 | 19.910 | 26.376 |

| Lev | 6487 | 0.445 | 0.212 | 0.045 | 0.967 |

| TobinQ | 6487 | 1.821 | 1.164 | 0.197 | 7.236 |

| Board | 6487 | 2.175 | 0.194 | 1.609 | 2.708 |

| Dual | 6487 | 0.195 | 0.396 | 0 | 1 |

| Top 1 | 6487 | 0.356 | 0.151 | 0.095 | 0.764 |

| Listage | 6487 | 2.452 | 0.706 | 0 | 3.332 |

| Variable | (1) MKP | (2) MKP | (3) MKP |

|---|---|---|---|

| GMA | 0.204 *** (12.01) | 0.092 *** (5.45) | 0.177 *** (7.967) |

| Size | 0.006 (0.99) | 0.100 *** (3.950) | |

| Lev | −0.091 *** (−3.89) | −0.024 *** (−3.332) | |

| TobinQ | −0.007 ** (−2.21) | −0.014 *** (−3.930) | |

| Board | −0.073 *** (−2.88) | −0.025 (−0.992) | |

| Dual | 0.003 (0.31) | −0.002 (−0.178) | |

| Top 1 | 0.001 *** (2.81) | 0.002 *** (3.701) | |

| Listage | 0.156 *** (18.91) | 0.025 ** (2.027) | |

| Constant | 1.219 *** (74.25) | 0.877 *** (6.40) | 1.091 *** (4.518) |

| Ind-fixed effect | YES | YES | YES |

| Time-fixed effect | YES | YES | YES |

| R2 | 0.002 | 0.018 | 0.782 |

| N | 6487 | 6487 | 6487 |

| Variable | (1) 1:1 PSM | (2) 1:3 PSM | (3) CEM | (4) EBM |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GMA | 0.139 *** (3.872) | 0.172 *** (4.171) | 0.259 *** (4.069) | 0.093 *** (5.764) |

| Constant | 0.948 ** (2.110) | 1.351 *** (2.312) | 5.725 * (1.713) | 1.386 *** (4.561) |

| Control variables | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Ind-fixed effect | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Time-fixed effect | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| R2 | 0.892 | 0.821 | 0.984 | 0.816 |

| N | 1038 | 2112 | 409 | 6487 |

| Variable | (1) Interaction Fixed Effects | (2) Replace the Explained Variable | (3) Replace the Explanatory Variable | (4) Eliminate Policy Interference | (5) Replace the Estimation Method | (6) Add Control Variables | (7) Exclude Multiple Green M&As |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GMA | 0.081 *** (4.862) | 0.103 *** (15.149) | 0.012 *** (5.618) | 0.059 *** (4.179) | 0.073 *** (6.164) | 0.085 *** (5.089) | 0.053 ** (2.269) |

| Constant | 1.632 *** (10.202) | −0.967 *** (−13.247) | 1.347 *** (7.521) | 1.735 ** (11.162) | 1.031 *** (10.216) | 1.324 *** (7.409) | 1.372 *** (5.520) |

| Green credit | 0.110 *** (14.618) | ||||||

| Low carbon | 0.078 *** (12.035) | ||||||

| Control variables | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Ind-fixed effect | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Time-fixed effect | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| R2 | 0.786 | 0.597 | 0.781 | 0.784 | 0.716 | 0.782 | 0.818 |

| N | 6487 | 6487 | 6487 | 6487 | 5613 | 6487 | 3172 |

| Variables | The First Stage | The Second Stage |

|---|---|---|

| GMA | MKP | |

| Dialect | 0.541 *** (4.546) | 0.050 ** (2.228) |

| Constant | −0.170 (−1.298) | 1.294 *** (6.861) |

| Control variables | YES | YES |

| Ind-fixed effect | YES | YES |

| Time-fixed effect | YES | YES |

| N | 6487 | 6487 |

| R2 | 0.880 | 0.820 |

| F | 131.84 *** | 43.87 *** |

| Unidentifiable test | 1610.69 *** | |

| Weak instrumental variable test | 2064.91 *** |

| Variable | (1) Two Years in Advance | (2) One Year in Advance | (3) One Year Delay | (4) Two Years in Delay |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GMA | 0.032 (1.575) | 0.014 (0.871) | 0.059 *** (3.395) | 0.027 (1.521) |

| Constant | 1.078 *** (5.121) | 1.324 *** (7.408) | 1.322 *** (7.068) | 1.295 *** (6.522) |

| Control variables | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Ind-fixed effect | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Time-fixed effect | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| R2 | 0.791 | 0.781 | 0.801 | 0.819 |

| N | 6487 | 6487 | 6487 | 6487 |

| Variable | (1) Gtfp | (2) Hum | (3) Bc |

|---|---|---|---|

| GMA | 0.101 *** (5.879) | 0.093 *** (6.103) | 0.585 *** (4.795) |

| Constant | 0.911 *** (4.409) | −0.668 *** (4.175) | 1.544 (1.405) |

| Control variables | YES | YES | YES |

| Ind-fixed effect | YES | YES | YES |

| Time-fixed effect | YES | YES | YES |

| R2 | 0.646 | 0.154 | 0.712 |

| N | 6487 | 6487 | 6487 |

| Variable | (1) Domestic | (2) Cross-Border |

|---|---|---|

| GMA | 0.096 *** (5.065) | 0.048 (1.395) |

| Constant | 1.281 *** (6.792) | 1.262 *** (3.655) |

| Control variables | YES | YES |

| Ind-fixed effect | YES | YES |

| Time-fixed effect | YES | YES |

| R2 | 0.779 | 0.789 |

| N | 1223 | 5264 |

| Variable | Heterogeneity of Property Rights | Heterogeneity of Life Cycle | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Non-State-Owned | (2) State-Owned | (3) Growing | (4) Mature | (5) Declining | |

| GMA | 0.096 *** (5.065) | 0.048 (1.395) | 0.038 (1.248) | 0.104 *** (3.243) | 0.054 * (1.680) |

| Constant | 1.281 *** (6.792) | 1.262 *** (3.655) | 0.883 ** (2.550) | 0.754 ** (2.175) | 0.043 (1.580) |

| Control variables | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Ind-fixed effect | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Time-fixed effect | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| R2 | 0.779 | 0.789 | 0.808 | 0.820 | 0.838 |

| N | 1223 | 5264 | 1935 | 2195 | 2357 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, W. The Impact of Green Mergers and Acquisitions on the Market Power of Heavily Polluting Enterprises. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6290. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146290

Fu Y, Wang Z, Zhao W. The Impact of Green Mergers and Acquisitions on the Market Power of Heavily Polluting Enterprises. Sustainability. 2025; 17(14):6290. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146290

Chicago/Turabian StyleFu, Yunpeng, Zixuan Wang, and Wenjia Zhao. 2025. "The Impact of Green Mergers and Acquisitions on the Market Power of Heavily Polluting Enterprises" Sustainability 17, no. 14: 6290. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146290

APA StyleFu, Y., Wang, Z., & Zhao, W. (2025). The Impact of Green Mergers and Acquisitions on the Market Power of Heavily Polluting Enterprises. Sustainability, 17(14), 6290. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146290