1. Introduction

Climate change is one of the greatest challenges facing humanity [

1] and a critical issue for governments worldwide. Human activities—especially greenhouse gas emissions—have caused significant climate disruptions, leading to more frequent extreme weather events and natural disasters. Examples include hurricanes in the U.S. in 2017, wildfires in Australia in 2020, and extreme heat and drought in southern China in 2022, all of which have intensified ecosystem vulnerability [

2]. In response to climate risks, governments are compelled to increase fiscal spending and often face declining tax revenues, thus reducing overall public revenue stability [

3,

4]. These risks are reshaping global production systems, geopolitical dynamics, and financial markets [

5,

6].

The concept of climate risk was first introduced in the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)’s 2001 assessment report, which emphasized both its likelihood and consequences. The 2017 G20 Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures further developed a framework for defining and categorizing climate risks. Broadly, climate risks can be classified into physical and transition risks [

7]. Physical risks stem from acute climate-related disasters—such as floods and typhoons—as well as chronic environmental changes like rising sea levels. These events can disrupt the real economy [

8,

9], damage fixed assets [

10,

11,

12,

13], halt business operations, and increase default risk [

14,

15]. In a globalized economy, these effects propagate through supply chains [

16], indirectly reducing consumption, dampening investment, and potentially triggering recessions. This in turn erodes firms’ collateral values and credit ratings [

17,

18,

19], affecting asset pricing in financial markets [

20,

21] and contributing to a rise in non-performing loans for banks.

In parallel, to advance low-carbon transitions and mitigate climate impact, governments are adopting regulatory measures such as carbon taxes. These policies drive firms to pursue green innovation, often involving high investment costs and the risk of transition failure [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26]. Meanwhile, shifting consumer preferences may lead to declining market shares and asset depreciation for high-carbon companies [

27,

28], further contributing to stock price volatility [

29]. Physical and transition risks are interconnected [

30]; although they operate through different channels, both transmit shocks from the real economy to the financial system [

31,

32], compounding into broader systemic risks. This intersection of environmental and climate economics has catalyzed a growing research field known as climate finance [

21,

33].

In the field of climate finance, assessing the impact of climate risk on asset pricing is a central topic—reflected in both credit and equity markets. Climate risks significantly influence corporate financing decisions [

34,

35]. Investors’ heightened sensitivity to climate-related risks can quickly translate into higher risk premiums, increasing capital costs, restricting access to financing, and ultimately reducing firms’ capacity to operate sustainably [

36]. The existing literature has extensively explored how climate risks affect equity financing and financing costs, reaching largely consistent conclusions. For instance, climate shocks prompt institutional investors to reduce holdings in firms with high climate risk exposure [

37]. Additionally, climate activism has depressed the stock prices of carbon-intensive companies [

38], while generating positive risk premiums in emerging market equities [

39].

The relationship between climate risks and corporate credit is also a growing area of interest [

40,

41]. This study focuses specifically on the link between climate risk and corporate debt financing [

42]. According to the pecking order theory, firms prefer debt over equity when seeking external capital [

43], and debt financing remains the dominant source of capital for Chinese firms [

44,

45]. However, climate risks complicate firms’ access to debt financing, affecting both supply and demand.

On the supply side, investors are more cautious when bonds are exposed to potential asset depreciation caused by climate change. For example, rising sea levels reduce residential property values, which is reflected in long-term mortgage pricing. Bond underwriters also face higher search costs when marketing climate-exposed bonds, which leads to higher bond yields [

21,

46] and, ultimately, increased borrowing costs [

47,

48,

49].

On the demand side, the scale of corporate debt financing is also shaped by climate risks. Yet, the findings are mixed. Some studies, drawing on static trade-off theory, argue that climate risk raises operational uncertainty and distress costs—including business disruptions, higher insurance premiums, and supply chain volatility—causing firms to adopt more conservative capital structures and reduce leverage [

50,

51,

52]. Conversely, other research suggests that climate uncertainty may increase leverage. In this view, firms respond to climate pressures by taking on more responsibility and investment, thereby increasing debt financing [

53,

54].

These divergent findings reflect varying research perspectives. Studies of corporate leverage tend to emphasize demand-side factors, though some acknowledge supply-side influences through increased debt costs. Research on debt financing costs, meanwhile, typically adopts a supply-side perspective, focusing on how climate risks affect financial institutions’ credit assessments and pricing.

This study bridges these perspectives by examining corporate debt financing capacity—defined by both the scale and cost of debt—in the context of climate risk. We argue that firms with strong operating performance, profitability, and growth potential [

55,

56], as well as effective governance structures, are less likely to default [

57,

58,

59]. For these firms, financial institutions face reduced information asymmetry and are more proactive in credit assessment. As climate risks intensify, banks are increasingly incorporating such risks into their credit decisions [

60], and financial regulators are embedding climate considerations into macroprudential policy frameworks [

61]. When firms face rising operational risks and uncertainty, default probabilities increase [

62,

63], prompting banks to tighten lending standards, reduce loan availability [

64], and raise risk premiums. Thus, changes in corporate debt financing capacity under climate risk are largely driven by credit rationing behavior among financial institutions, manifested as a reduced debt scale and higher interest rate risk premiums.

To validate the above arguments, we examine the role of corporate carbon emissions as a moderating variable within the context of China’s “dual carbon” goals. In an era of government-led green finance and green credit promotion, carbon emission levels have become a key indicator of corporate environmental responsibility, directly influencing firms’ financing behavior in capital markets [

65]. As environmental regulations in China tighten, firms face differentiated incentives and penalties, resulting in varied impacts on their carbon emissions [

66]. At the same time, the development of a green finance system channels capital toward low-carbon and environmentally friendly sectors, creating disparities in financial access based on firms’ carbon footprints [

67,

68].

Specifically, low-carbon firms are better aligned with the green finance agenda and are more likely to receive support through green credit, thus enjoying more favorable debt financing conditions. In contrast, high-carbon firms face stricter regulatory scrutiny and greater operational risks, placing them at a disadvantage in the debt market. Against this backdrop, we use changes in corporate carbon emissions as a moderating variable to test the causal effects of climate change risk on debt financing. We hypothesize that under similar levels of climate risk, firms that successfully reduce emissions will find it easier to obtain debt financing and will face lower financing costs. This would suggest that under the green credit regime, financial institutions allocate credit based on carbon emission levels—a supply-side mechanism—rather than corporate capital structure decisions.

Conversely, if no significant differences are observed, this would support the alternative view that changes in debt financing capacity due to climate risk are primarily driven by firms’ internal financing choices. In addition, our analysis investigates the mechanisms through which climate risks affect debt financing capacity and explores heterogeneity across firms and regions.

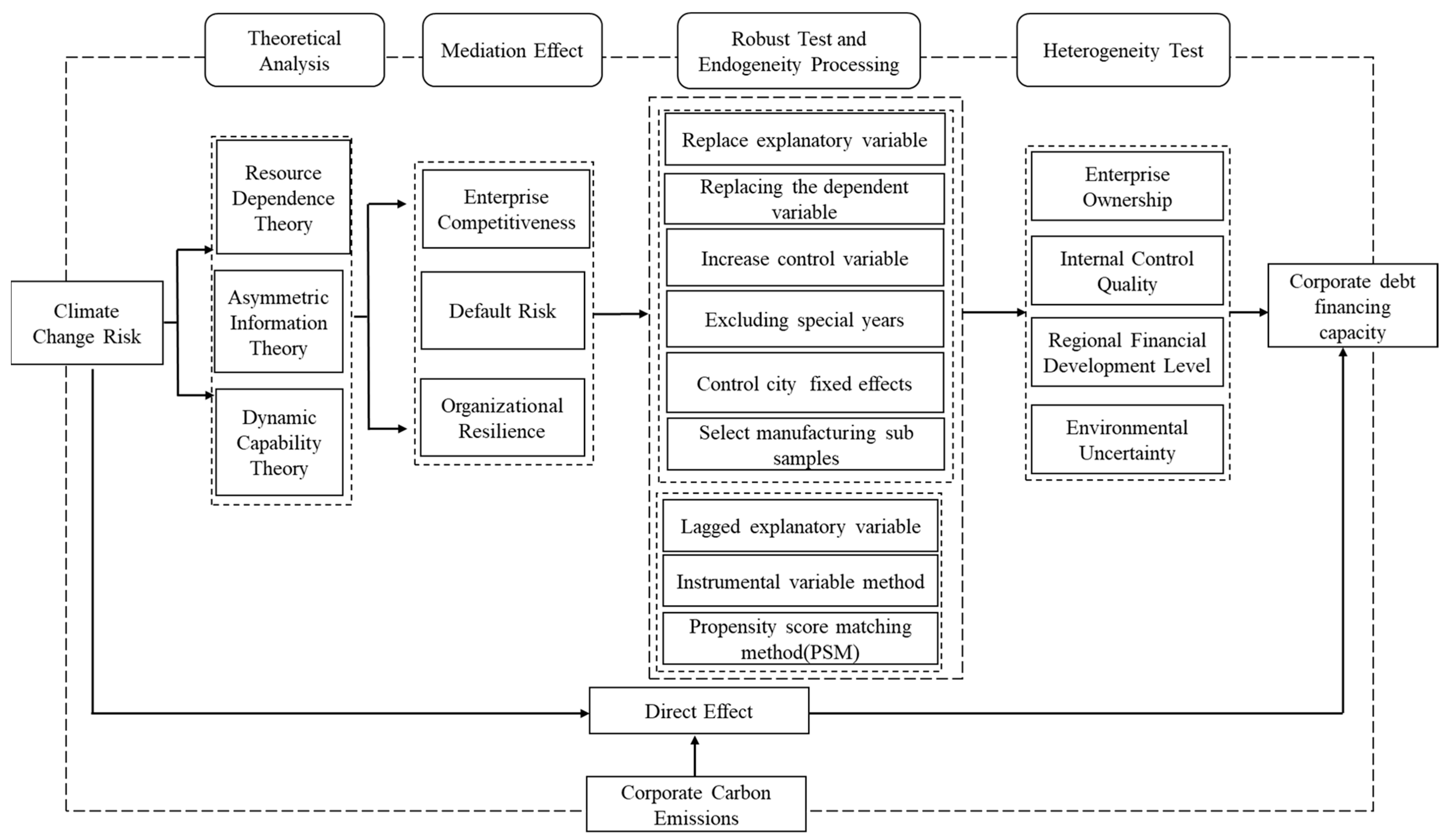

Compared to previous research, this study presents several key innovations and contributions: (1) As climate change risks increasingly affect businesses, the relationship between these risks and debt financing remains ambiguous. This study adopts climate change risk as an explanatory variable and explores its effects on corporate debt financing capacity from the perspectives of debt volume and financing costs, while also examining the underlying mechanisms. (2) Current assessments of climate change risk often rely on extreme weather events such as heatwaves, droughts, and heavy rains. However, these indicators fail to capture the significant risks associated with the transition to a low-carbon economy and do not provide a comprehensive view of climate change risk. Furthermore, as extreme weather events are closely tied to geographical locations, they may not be suitable for micro-level firms. To address this limitation, this study utilizes textual analysis to evaluate corporate-level climate change risk by analyzing keywords related to climate change in annual reports. Firstly, the climate change risk indicator developed through textual analysis can extract multidimensional information, thereby overcoming the limitations of macro-geographic indicators that typically reflect only a single dimension of quantitative data and mitigating biases associated with the examination of individual indicators. Secondly, unlike macro-geographic indicators, which primarily rely on meteorological stations or satellite data that have lower temporal resolution and static characteristics, the indicators constructed at the enterprise level through textual analysis offer higher spatial and temporal resolution. They are capable of capturing dynamic feedback from human systems regarding climate change, which helps prevent the oversight of subtle socio-economic impacts. Finally, the integration of textual analysis and machine learning enables the processing of richer descriptive information and unstructured text, resulting in a more comprehensive and accurate assessment of climate change risk. (3) Given the close relationship between corporate carbon emissions and access to credit under China’s green credit policy, this study investigates the moderating role that carbon emissions play in the relationship between climate change risk and corporate debt financing capacity. It further examines how changes in corporate carbon emissions affect the connection between climate change and debt financing, thereby providing a theoretical foundation for understanding how climate change risk influences corporate debt financing through the actions of financial institutions. (4) Additionally, this study explores the mechanisms by which climate change risk undermines corporate debt financing capacity, identifying factors such as reduced competitiveness, increased default risk, and diminished organizational resilience. A heterogeneous analysis is conducted across four dimensions: ownership structure, internal control quality, regional financial development, and environmental uncertainty, further revealing factors that may modify the relationship between climate change risk and corporate debt financing.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 reviews existing research by synthesizing and summarizing the literature on climate change risk and corporate debt financing capacity, analyzing the logical relationship between the two through relevant theoretical frameworks, and subsequently formulating research hypotheses.

Section 3 constructs the research framework, detailing the data sources and measurement methods for the variables, and establishes the research model.

Section 4 conducts a comprehensive empirical analysis and validation. First, it examines the impact of climate change risk on corporate debt financing capacity. To ensure the robustness of the results, a series of robustness checks and endogeneity treatments are performed, specifically focusing on the moderating role of corporate carbon emissions in the relationship between climate change risk and corporate debt financing capacity. Additionally, the mediating effects of competitiveness, default risk, and organizational resilience are assessed, along with multiple heterogeneity tests. In

Section 5, we conclude the study, highlighting the key contributions while also addressing the limitations encountered during our research. Finally,

Section 6 offers targeted recommendations for businesses, financial institutions, and government policymakers. The overall research framework is illustrated in

Figure 1.

5. Conclusions

This study utilizes data from A-share listed companies in China spanning from 2010 to 2022 to examine the impact of climate change risks on corporate debt financing capacity. The empirical results indicate that, after controlling for potential influencing factors, climate change risks significantly diminish a firm’s ability to finance through debt. Specifically, the findings reveal a decrease in debt financing volume and an increase in the cost of debt capital. This core conclusion remains robust even after a series of checks for robustness and treatments for endogeneity.

These findings expand the research landscape in climate finance and green finance, reconciling existing discrepancies by unifying perspectives on how climate change risks affect both debt financing volume and cost. The results suggest that the influence primarily originates from the supply side, rather than being driven by corporate capital structure decisions or the risk assessments performed by credit institutions. To further validate this perspective, the study introduces changes in corporate carbon emissions as a moderating variable, demonstrating that fluctuations in carbon emissions guide credit funding and exert a negative moderating effect on the relationship between climate change risks and debt financing capacity. This indirectly supports the notion that both debt volume and capital cost are influenced by the actions of supply-side financial institutions. Moreover, this research explores the pathways through which climate change risks undermine corporate debt financing capability. These include diminished competitiveness, increased default risks, and reduced organizational resilience. Heterogeneity analyses reveal that the impact of climate change risks on debt financing capacity varies according to ownership structure, internal control quality, regional financial development levels, and the degree of external environmental uncertainty. Notably, the suppressive effect of climate change risks on debt financing capacity is stronger in non-state-owned enterprises, firms with lower internal control quality, companies operating in regions with higher financial development, and environments characterized by greater uncertainty.

Given the growing implications of climate change, these results elucidate the relationship between climate change risks and corporate debt financing capacity. They offer valuable insights into understanding the risks posed by climate change, adapting to and mitigating these risks, guiding capital flows, facilitating industrial transformation, and promoting low-carbon sustainable economic development.

However, the study acknowledges certain limitations, particularly concerning the measurement of climate change risks, which rely on annual report disclosures and may contain noise and interference. This suggests opportunities for future research in this area. A scientifically sound assessment and measurement of micro-level corporate climate change risks will be crucial for further investigation. Additionally, given that dual carbon targets are specific policies set by the Chinese government, further examination is needed to determine the applicability of these conclusions to climate finance practices in other countries.

6. Policy and Managerial Suggestions

Our research offers valuable insights for formulating green policies and guiding corporate sustainable development decisions. We have clarified the impact of climate change risk on corporate debt financing capacity, which is essential for shaping corporate strategies and operational adjustments. By identifying the underlying mechanisms, this research can help firms restructure their business models, enhance organizational resilience, and proactively address climate change. Furthermore, it can assist financial institutions in optimizing operations, refining risk assessment models, reducing credit risk, innovating financial products and services, and improving the efficiency of financial resource allocation, thereby contributing to stability in financial markets. Policymakers, who are responsible for facilitating a green economic transition and ensuring social stability, can leverage these findings to inform decision-making and enhance governance.

Based on our empirical results, we propose the following recommendations:

Firstly, banks and financial institutions, as the pricing agents for climate change risks and lenders, need to enhance their risk assessment systems by integrating climate change risks into their corporate credit risk evaluation models and incorporating a climate risk scoring module into the credit approval process. They should develop climate risk stress testing models to assess potential losses in loan portfolios under various climate disaster scenarios. Additionally, expanding their analysis of relevant soft indicators related to corporate climate change risks will provide a deeper understanding of firms’ dynamic capabilities in addressing these challenges. Financial institutions can also issue green bonds and sustainability-linked loans to provide dedicated funding for companies effectively managing climate change risks, thereby increasing the supply of climate-related credit; promote climate-linked loans by dynamically tying loan interest rates and terms to the climate performance indicators of borrowing enterprises, facilitating their emission reduction efforts; integrate data from the CDP platform and employ Internet of Things (IoT) technology for real-time monitoring; require high-risk sector borrowers to install sensor networks (e.g., monitoring water levels and temperatures in factories) that connect directly to the bank’s risk management platform, enhancing post-loan monitoring and activating risk mitigation mechanisms based on climate risk thresholds; and establish dedicated climate risk reserves for enterprises categorized by varying risk levels to finance debt relief or technological upgrades necessitated by climate events.

Secondly, at the corporate level, firms should conduct systematic assessments of the physical and transition risks associated with climate change. This involves establishing dedicated climate risk management teams within their risk management departments and regularly performing climate scenario stress tests, such as simulating the impacts of extreme weather events on supply chain disruptions. Collaboration with research institutions to develop climate risk early warning systems is essential for effectively monitoring these physical and transition risks. Companies should also actively pursue the green transformation of their supply chains, set clear timelines for phasing out outdated capacities, and invest in forestry carbon sink projects to help offset their carbon emissions. Furthermore, enhancing both the quantity and quality of disclosures related to climate change risks and their mitigation strategies is crucial. Firms should publish independent climate-themed reports as part of their annual reports to improve information symmetry. Simultaneously, strengthening internal control quality can help reduce creditors’ misjudgments regarding climate change risks.

Finally, the government needs to actively guide the flow of low-carbon funds and improve relevant policies within the green finance system. This includes increasing financial subsidies and tax incentives related to climate change responses, establishing special funds for green technology development, and implementing differentiated carbon taxes for companies based on their carbon emissions. Enhanced financial support, particularly for non-state-owned enterprises, is crucial to helping them overcome credit constraints arising from climate risks. For instance, the government should implement state-backed loans and establish a climate whitelist for non-state-owned enterprises, enabling them to benefit from expedited loan approvals and preferential interest rates. Additionally, it should provide purchase and interest subsidies for green transformation investments in these enterprises and offer preferential treatment in green government procurement to support their sustainable initiatives. A stable policy framework targeting climate change risks should be established that promotes standardized regulations for climate information disclosure to reduce uncertainties resulting from policy fluctuations. Additionally, a national-level climate information-sharing platform for enterprises should be created to integrate carbon emissions data and other relevant information. This would increase the information available to financial institutions and help reduce information asymmetry between these institutions and companies. From a long-term development perspective, the government can implement integrated policies that focus on financial optimization, green infrastructure, and technological support in ecologically vulnerable areas. By creating replicable models through pilot programs, the government can fundamentally enhance enterprises’ capabilities to address climate change risks.