Interaction Between Ethical Leadership, Affective Commitment and Social Sustainability in Transition Economies: A Model Mediated by Ethical Climate and Moderated by Psychological Empowerment in the Colombian Electricity Sector

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Study Contextualization

1.2. Linear Link Between Ethical Leadership-Affective Commitment

1.3. Ethical Leadership—Affective Commitment Through the Mediating Effect of Ethical Climate

1.4. Psychological Empowerment as a Moderating Factor

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Ethical Leadership

2.2.2. Ethical Climate

2.2.3. Psychological Empowerment

2.2.4. Affective Commitment

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

3.2. Descriptive Statistics and Discriminant Validity

3.3. Mediating Effect Analysis

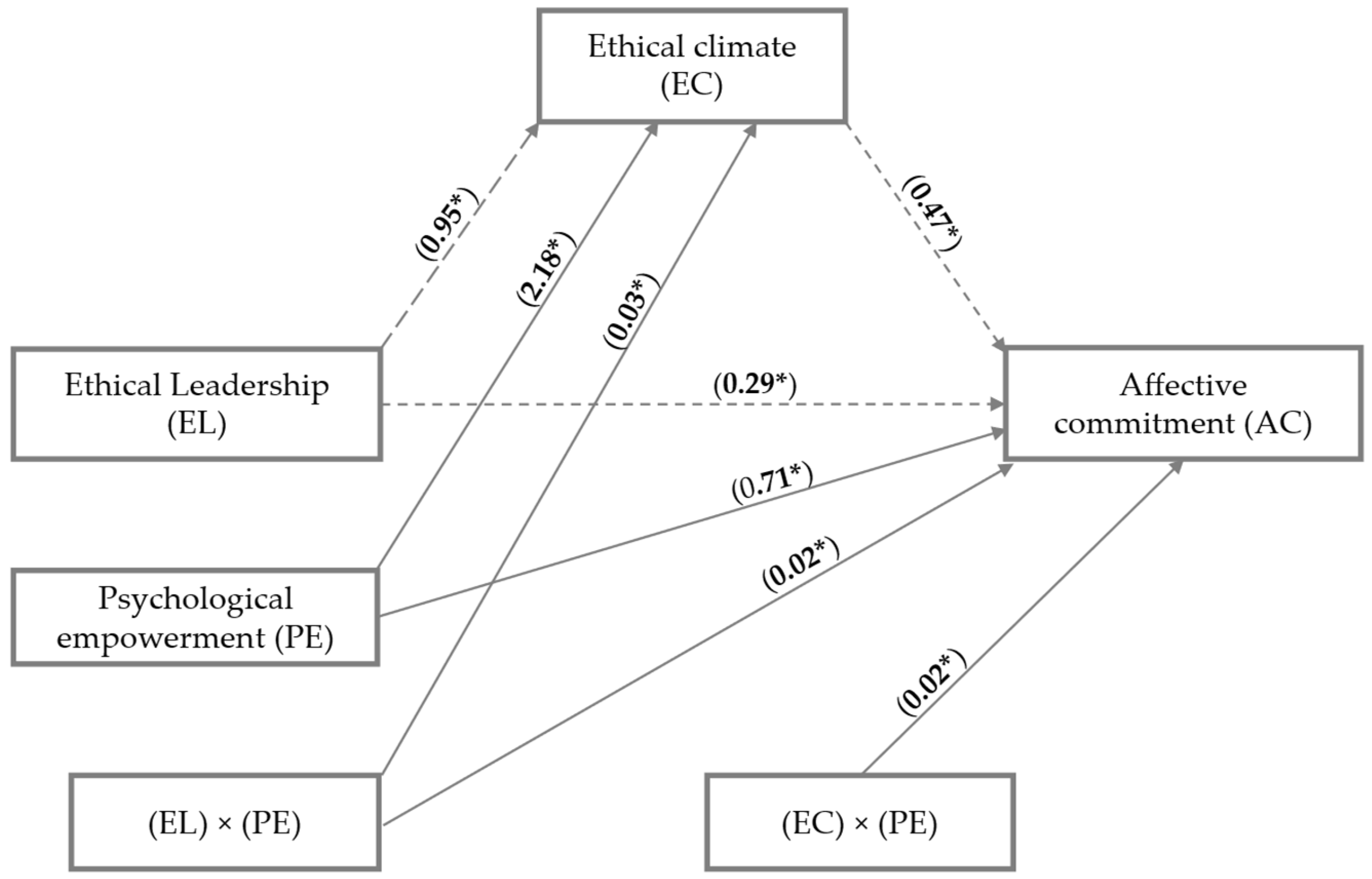

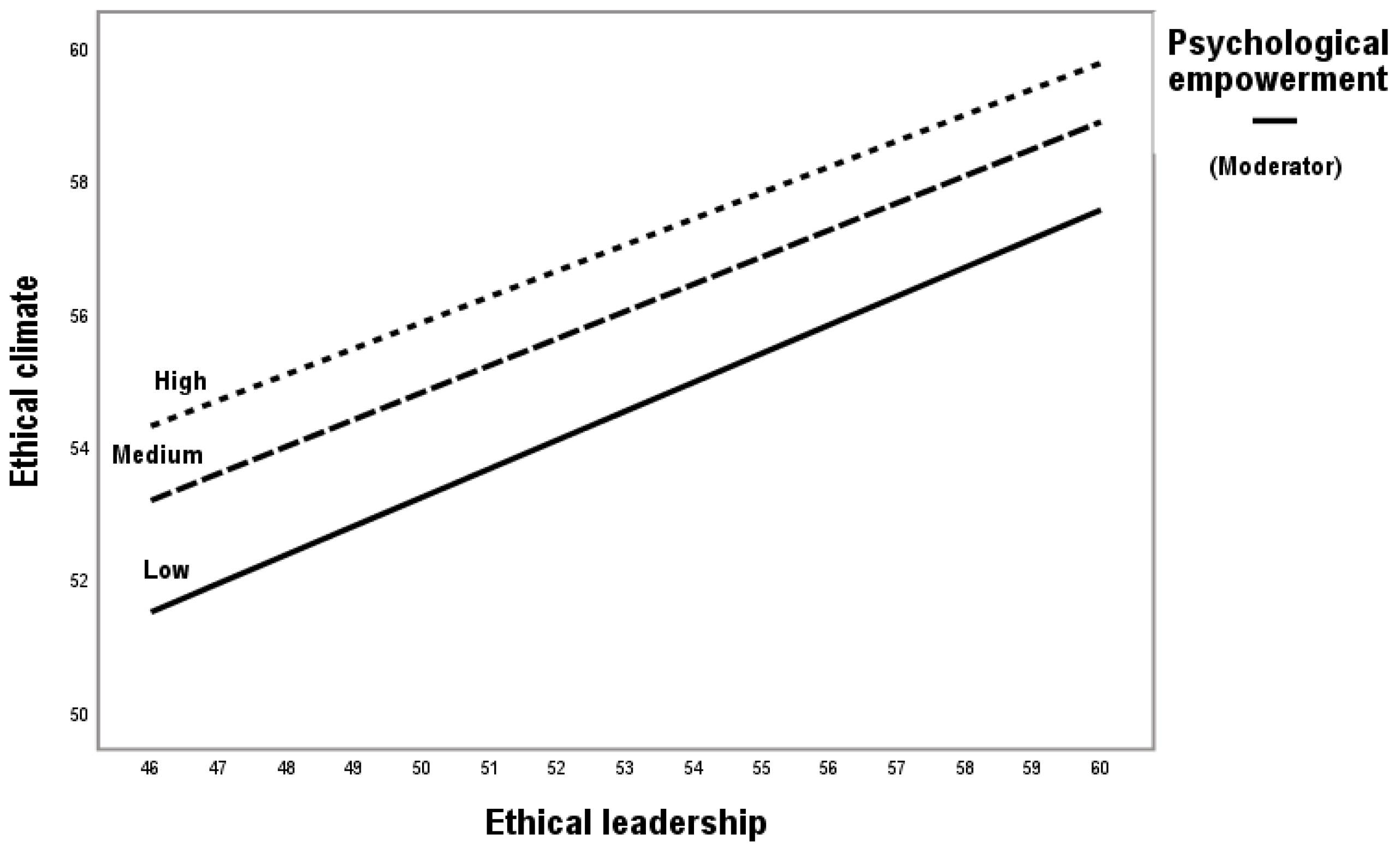

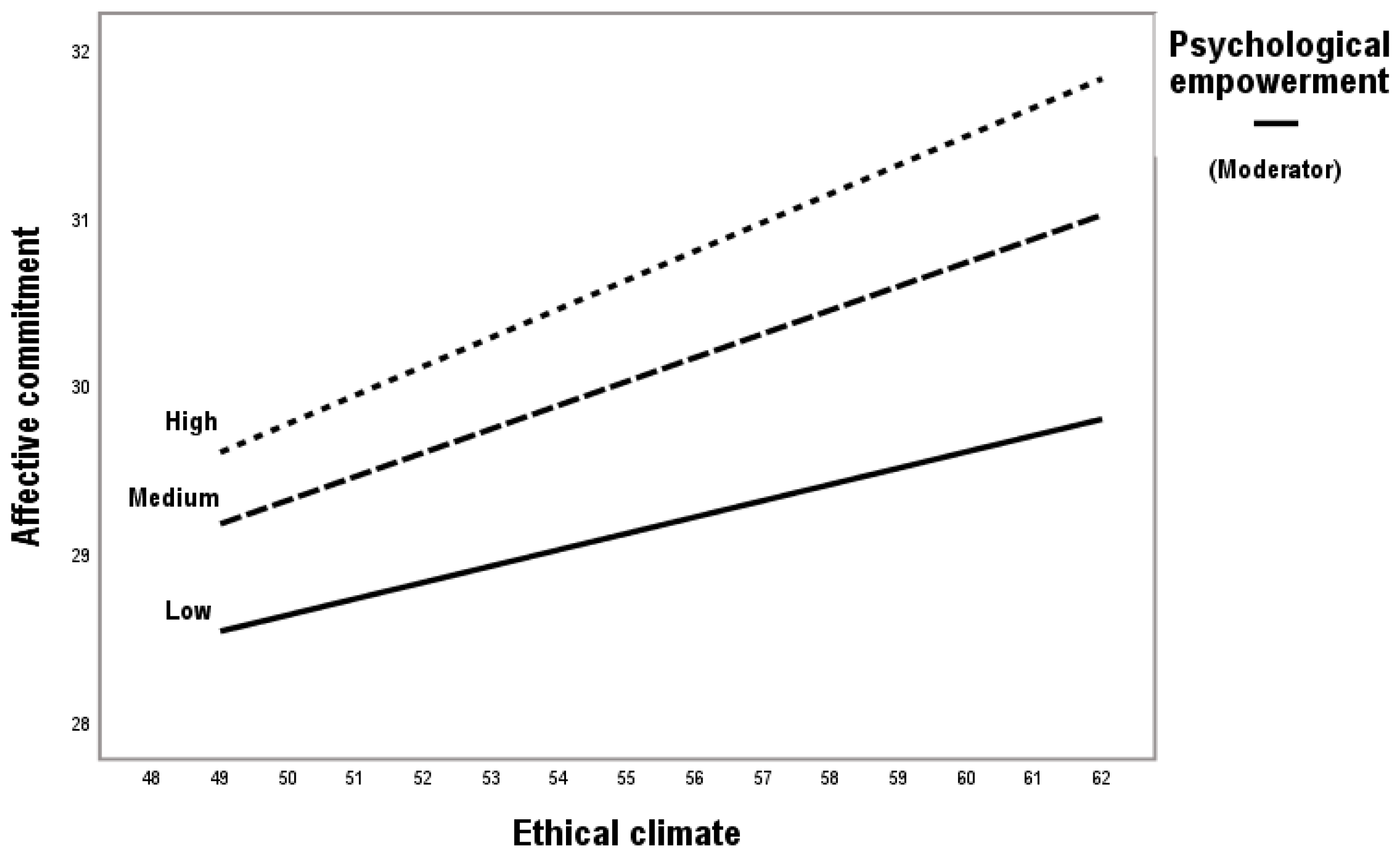

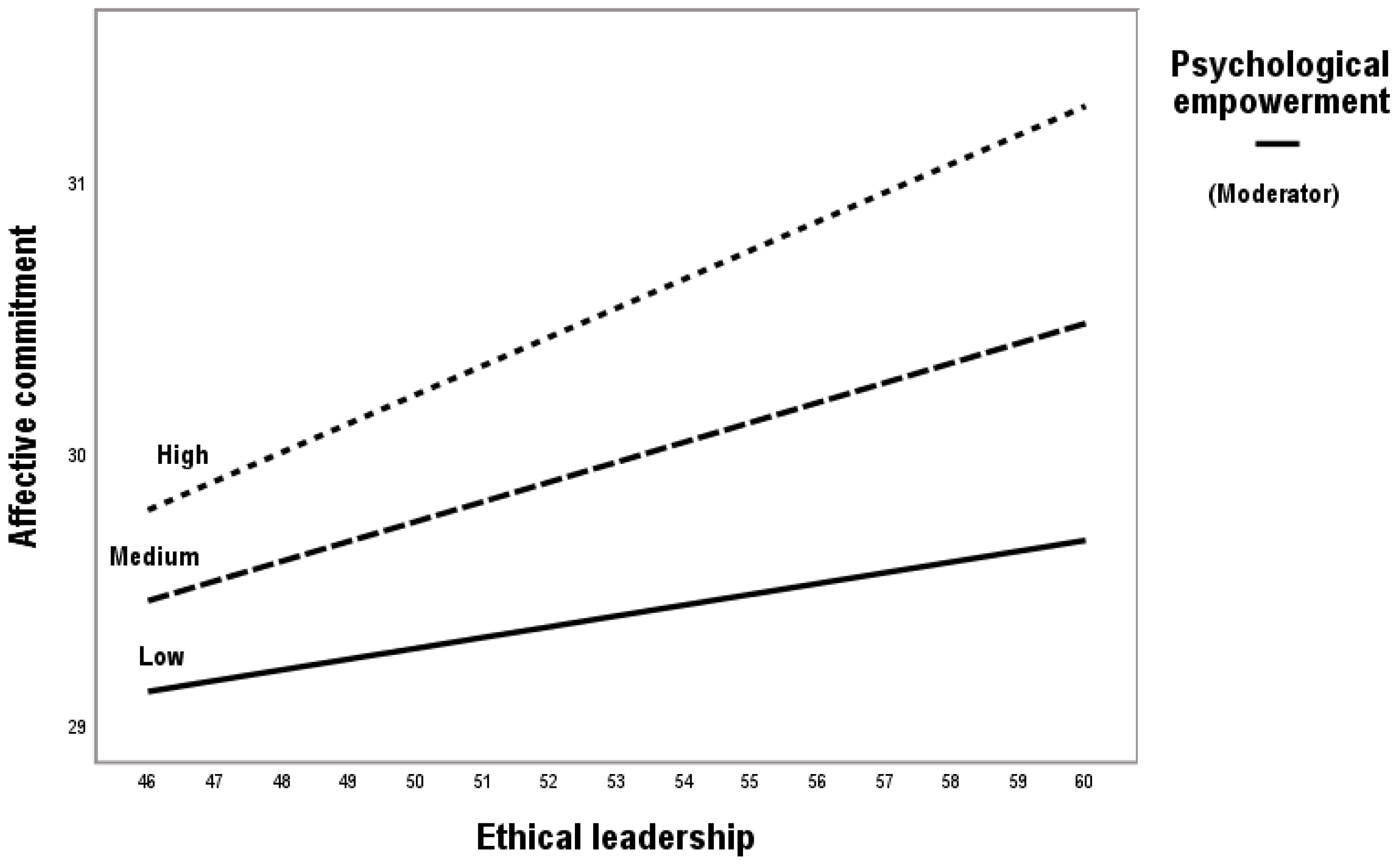

3.4. Moderated Mediation Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Theoretical Implications

4.2. Practical Implications

4.3. Limitations and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CFA | confirmatory factor analysis |

| GFI | goodness of fit index |

| RMSR | mean squared residual |

| RMSEA | root mean square error of approximation |

| IFI | incremental fit index |

| NFI | normed fit index |

| CFI | comparative fit index |

| N | number of items |

| M | means |

| SD | standard deviations |

| EC | ethical climate |

| EL | ethical leadership |

| PE | psychological empowerment |

| AC | affective commitment |

| AVE | average variance extracted |

| DV | discriminant validity |

| CFC | composite reliability |

| CR | critical coefficients |

| IM | intrinsic motivation |

References

- Suhonen, R.; Stolt, M.; Virtanen, H.; Leino-Kilpi, H. Organizational ethics: A literature review. Nurs. Ethics 2011, 18, 285–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demirtas, O.; Akdogan, A.A. The Effect of Ethical Leadership Behavior on Ethical Climate, Turnover Intention, and Affective Commitment. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 130, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Halbusi, H.; Ruiz-Palomino, P.; Morales-Sánchez, R.; Abdel Fattah, F.A.M. Managerial ethical leadership, ethical climate and employee ethical behavior: Does moral attentiveness matter? Ethics Behav. 2021, 31, 604–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Halbusi, H.; Williams, K.A.; Mansoor, H.O.; Hassan, M.S.; Hamid, F.A.H. Examining the impact of ethical leadership and organizational justice on employees’ ethical behavior: Does person–organization fit play a role? Ethics Behav. 2019, 30, 514–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, H.; Zhu, L.; Jin, X. Construed Organizational Ethical Climate and Whistleblowing Behavior: The Moderated Mediation Effect of Person–Organization Value Congruence and Ethical Leader Behavior. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, M.; Bhattacharjee, S.; Mahmood, M.; Uddin, M.A.; Biswas, S.R. Ethical leadership for better sustainable performance: Role of employee values, behavior and ethical climate. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 337, 130527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Vandenberghe, C. Ethical Leadership and Team Ethical Voice and Citizenship Behavior in the Military: The Roles of Team Moral Efficacy and Ethical Climate. Group Organ. Manag. 2020, 45, 514–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.E.; Treviño, L.K.; Harrison, D.A. Ethical leadership: A social learning perspective for construct development and testing. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2005, 97, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamilah, M.; Mamduh, U.; Damayanti, I.A.; Anshori, M.I. Ethical Leadership: Literature Study. Indones. J. Contemp. Multidiscip. Res. 2023, 2, 655–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.-J.; Kim, M.-J.; Kim, T.-H. “The Power of Ethical Leadership”: The Influence of Corporate Social Responsibility on Creativity, the Mediating Function of Psychological Safety, and the Moderating Role of Ethical Leadership. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.J.; Cho, J.; Baek, Y.; Pillai, R.; Oh, S.H. Does ethical leadership predict follower outcomes above and beyond the full-range leadership model and authentic leadership?: An organizational commitment perspective. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2019, 36, 821–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Halbusi, H.; Williams, K.A.; Ramayah, T.; Aldieri, L.; Vinci, C.P. Linking Ethical leadership and ethical climate to employees’ ethical behavior: The moderating role of person–organization fit. Pers. Rev. 2021, 50, 159–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victor, B.; Cullen, J.B. The Organizational Bases of Ethical Work Climates. Adm. Sci. Q. 1988, 33, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradesa, H.A.; Dawud, J.; Affandi, M.N. Mediating Role of Affective Commitment in The Effect of Ethical Work Climate on Felt Obligation Among Public Officers. JEMA J. Ilm. Bid. Akunt. Dan Manaj. 2019, 16, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Halbusi, H.; Tang, T.L.P.; Williams, K.A.; Ramayah, T. Do ethical leaders enhance employee ethical behaviors? Organizational justice and ethical climate as dual mediators and leader moral attentiveness as a moderator: Empirical support from Iraq’s emerging market. In Monetary Wisdom; Tang, T.L.-P., Ed.; Academic Press: Murfreesboro, TN, USA, 2024; pp. 317–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, J.B.; Parboteeah, K.P.; Victor, B. The Effects of Ethical Climates on Organizational Commitment: A Two-Study Analysis. J. Bus. Ethics 2003, 46, 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.P.; Maltin, E.R. Employee commitment and well-being: A critical review, theoretical framework and research agenda. J. Vocat. Behav. 2010, 77, 323–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.-S.; Lin, C.-C. The Effects of Ethical Leadership and Ethical Climate on Employee Ethical Behavior in the International Port Context. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 124, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loi, R.; Lam, L.W.; Ngo, H.Y.; Cheong, S. Exchange mechanisms between ethical leadership and affective commitment. J. Manag. Psychol. 2015, 30, 645–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, M.; Qing, M.; Hwang, J.; Shi, H. Ethical Leadership, Affective Commitment, Work Engagement, and Creativity: Testing a Multiple Mediation Approach. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Işik, A.N. Ethical leadership and school effectiveness: The mediating roles of affective commitment and job satisfaction. Int. J. Educ. Leadersh. Manag. 2020, 8, 60–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.-C.; You, C.-S.; Tsai, M.-T. A multidimensional analysis of ethical climate, job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and organizational citizenship behaviors. Nurs. Ethics 2012, 19, 513–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, J. Exploring relationships among ethical climate types and organizational commitment. J. Indian Bus. Res. 2017, 9, 20–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahraei Beiranvand, M.; Beiranvand, S.; Beiranvand, S.; Mohammadipour, F. Explaining the effect of authentic and ethical leadership on psychological empowerment of nurses. J. Nurs. Manag. 2021, 29, 1081–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spreitzer, G.M. Psychological Empowerment in the Workplace: Dimensions, Measurement, and Validation. Acad. Manag. J. 1995, 38, 1442–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qing, M.; Asif, M.; Hussain, A.; Jameel, A. Exploring the impact of ethical leadership on job satisfaction and organizational commitment in public sector organizations: The mediating role of psychological empowerment. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2020, 14, 1405–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Vandenberghe, C. Ethical leadership and organizational commitment: The dual perspective of social exchange and empowerment. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2021, 42, 976–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkoç, İ.; Türe, A.; Arun, K.; Okun, O. Mediator effects of psychological empowerment between ethical climate and innovative culture on performance and innovation in nurses. J. Nurs. Manag. 2022, 30, 2324–2334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Jin, J. The relationships of ethical climate, physician–nurse collaboration and psychological empowerment with critical care nurses’ ethical conflict in China: A structural equation model. J. Nurs. Manag. 2022, 30, 2434–2441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Otaibi, S.M.; Amin, M.; Winterton, J.; Bolt, E.E.T.; Cafferkey, K. The role of empowering leadership and psychological empowerment on nurses’ work engagement and affective commitment. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2023, 31, 2536–2560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; You, Y.; Zhu, J. Principal–Teacher Management Communication and Teachers’ Job Performance: The Mediating Role of Psychological Empowerment and Affective Commitment. Asia-Pac. Educ. Res. 2020, 29, 365–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yogalakshmi, J.A.; Suganthi, L. Impact of perceived organizational support and psychological empowerment on affective commitment: Mediation role of individual career self-management. Curr. Psychol. 2020, 39, 885–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Sun, X.; Lu, J.; He, Y. How Ethical Leadership Prompts Employees’ Voice Behavior? The Roles of Employees’ Affective Commitment and Moral Disengagement. Front. Psychol. 2022, 12, 732463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahadori, M.; Ghasemi, M.; Hasanpoor, E.; Hosseini, S.M.; Alimohammadzadeh, K. The influence of ethical leadership on the organizational commitment in fire organizations. Int. J. Ethics Syst. 2021, 37, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, K.; Lin, W.; Li, J.C.; Wang, L. Employee Trust in Supervisors and Affective Commitment. Psychol. Rep. 2016, 118, 829–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmawa, I.W.G.; Widyani, A.A.D.; Sugianingrat, I.A.P.W.; Martini, I.A.O. Ethical entrepreneurial leadership and organizational trust for organizational sustainability. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2020, 7, 1818368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Z.C.; Tan, C.E.; Choong, Y.O. Occupational Safety & Health Management and Corporate Sustainability: The Mediating Role of Affective Commitment. Saf. Health Work 2023, 14, 415–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilyas, S.; Abid, G.; Ashfaq, F. Ethical leadership in sustainable organizations: The moderating role of general self-efficacy and the mediating role of organizational trust. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2020, 22, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, D.M.; Kuenzi, M.; Greenbaum, R.L. Examining the Link Between Ethical Leadership and Employee Misconduct: The Mediating Role of Ethical Climate. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 95 (Suppl. S1), 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Torner, C.; Corral-Marfil, J.A.; Tarrats-Pons, E. The relationship between ethical leadership and emotional exhaustion in a virtual work environment: A moderated mediation model. Systems 2024, 12, 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Torner, C. Ethical leadership and benevolent climate. The mediating effect of creative self-efficacy and the moderator of continuance commitment. Rev. Galega Econ. 2023, 32, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloustani, S.; Atashzadeh-Shoorideh, F.; Zagheri-Tafreshi, M.; Nasiri, M.; Barkhordari-Sharifabad, M.; Skerrett, V. Association between ethical leadership, ethical climate and organizational citizenship behavior from nurses’ perspective: A descriptive correlational study. BMC Nurs. 2020, 19, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali Awad, N.H.; Al-anwer Ashour, H.M. Crisis, ethical leadership and moral courage: Ethical climate during COVID-19. Nurs. Ethics 2022, 29, 1441–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. Self-referent mechanisms in social learning theory. Am. Psychol. 1979, 34, 439–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Model of Causality in Social Learning Theory. In Cognition and Psychotherapy; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1985; pp. 81–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A.; Barbaranelli, C.; Caprara, G.V.; Pastorelli, C. Self-Efficacy Beliefs as Shapers of Children’s Aspirations and Career Trajectories. Child Dev. 2001, 72, 187–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumjaun, A.; Narod, F. Social Learning Theory—Albert Bandura. In Science Education in Theory and Practice; Akpan, B., Kennedy, T.J., Eds.; Springer Texts in Education; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grojean, M.W.; Resick, C.J.; Dickson, M.W.; Smith, D.B. Leaders, Values, and Organizational Climate: Examining Leadership Strategies for Establishing an Organizational Climate Regarding Ethics. J. Bus. Ethics 2004, 55, 223–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schminke, M.; Ambrose, M.L.; Neubaum, D.O. The effect of leader moral development on ethical climate and employee attitudes. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2005, 97, 135–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özden, D.; Arslan, G.G.; Ertuğrul, B.; Karakaya, S. The effect of nurses’ ethical leadership and ethical climate perceptions on job satisfaction. Nurs. Ethics 2019, 26, 1211–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y. CEO Ethical Leadership, Ethical Climate, Climate Strength, and Collective Organizational Citizenship Behavior. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 108, 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, M.-T.; Huang, C.-C. The Relationship among Ethical Climate Types, Facets of Job Satisfaction, and the Three Components of Organizational Commitment: A Study of Nurses in Taiwan. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 80, 565–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.J.; Bashir, F.; Nasim, I.; Ahmad, R. Understanding Affective, Normative & Continuance Commitment through the Lens of Training & Development. IRASD J. Manag. 2021, 3, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odoardi, C.; Battistelli, A.; Montani, F.; Peiró, J.M. Affective Commitment, Participative Leadership, and Employee Innovation: A Multilevel Investigation. Rev. Psicol. Trab. Las Organ. 2019, 35, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llorente-Alonso, M.; García-Ael, C.; Topa, G. A meta-analysis of psychological empowerment: Antecedents, organizational outcomes, and moderating variables. Curr. Psychol. 2024, 43, 1759–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibi, A.; Afsar, B. Leader-member exchange and innovative work behavior: The role of intrinsic motivation, psychological empowerment, and creative process engagement. Perspect. Innov. Econ. Bus. 2018, 18, 25–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dust, S.B.; Resick, C.J.; Margolis, J.A.; Mawritz, M.B.; Greenbaum, R.L. Ethical leadership and employee success: Examining the roles of psychological empowerment and emotional exhaustion. Leadersh. Q. 2018, 29, 570–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Chen, J. How Does Psychological Empowerment Prevent Emotional Exhaustion? Psychological Safety and Organizational Embeddedness as Mediators. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 546687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghani-Tafti, M.; Barkhordari-Sharifabad, M.; Nasiriani, K.; Fallahzadeh, H. Ethical leadership, psychological empowerment and caring behavior from the nurses’ perspective. Clin. Ethics 2022, 17, 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almasradi, R.B.; Sarwar, F.; Droup, I. Authentic Leadership and Socially Responsible Behavior: Sequential Mediation of Psychological Empowerment and Psychological Capital and Moderating Effect of Perceived Corporate Social Responsibility. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.-S.; Thapa, B. Relationship of Ethical Leadership, Corporate Social Responsibility and Organizational Performance. Sustainability 2018, 10, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Torner, C.; Corral-Marfil, J.A.; Jiménez-Pérez, Y.; Tarrats-Pons, E. Impact of Ethical Leadership on Autonomy and Self-Efficacy in Virtual Work Environments: The Disintegrating Effect of an Egoistic Climate. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochoa Pacheco, P.; Coello-Montecel, D.; Tello, M. Psychological Empowerment and Job Performance: Examining Serial Mediation Effects of Self-Efficacy and Affective Commitment. Adm. Sci. 2023, 13, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seibert, S.E.; Wang, G.; Courtright, S.H. Antecedents and consequences of psychological and team empowerment in organizations: A meta-analytic review. J. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 96, 981–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, J.-H.; Xiang, X.-T.; Shen, L. The impact of teachers’ organizational silence on job performance: A serial mediation effect of psychological empowerment and organizational affective commitment. Asia Pac. J. Educ. 2024, 44, 355–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, H.; Fanbo, M.; Patwary, A.K. Examining Organizational Commitment to Environmental Performances Among Hotel Employees: The Role of Ethical Leadership, Psychological Ownership and Psychological Empowerment. Sage Open 2024, 14, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, B.; Khan, A.A.; Bashir, S.; Arjoon, S. Impact of ethical leadership on creativity: The role of psychological empowerment. Curr. Issues Tour. 2017, 20, 839–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedgwick, P. Stratified cluster sampling. BMJ 2013, 347, f7016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, H.D.; Căpușneanu, S.; Javed, T.; Rakos, I.-S.; Barbu, C.M. The Mediating Role of Attitudes towards Performing Well between Ethical Leadership, Technological Innovation, and Innovative Performance. Adm. Sci. 2024, 14, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, J.; Opoku-Dakwa, A. Ethical Work Climate 2.0: A Normative Reformulation of Victor and Cullen’s 1988 Framework. J. Bus. Ethics 2022, 178, 629–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.P.; Allen, N.J.; Smith, C.A. Commitment to organizations and occupations: Extension and test of a three-component conceptualization. J. Appl. Psychol. 1993, 78, 538–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.G.; Zhu, W.; Kwon, B.; Bang, H. Ethical leadership and follower unethical pro-organizational behavior: Examining the dual influence mechanisms of affective and continuance commitments. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2023, 34, 4313–4343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R.W. Cross-Cultural Research Methods. In Environment and Culture; Altman, I., Rapoport, A., Wohlwill, J.F., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1980; Volume 4, pp. 47–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, N.P. Sources of Method Bias in Social Science Research and Recommendations on How to Control It. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2012, 63, 539–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Software review: Software programs for structural equation modeling: Amos, EQS, and LISREL. J. Psychoeduc. Assess. 1998, 16, 343–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Partial, conditional, and moderated moderated mediation: Quantification, inference, and interpretation. Commun. Monogr. 2018, 85, 4–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonett, D.G.; Wright, T.A. Cronbach’s alpha reliability: Interval estimation, hypothesis testing, and sample size planning. J. Organ. Behav. 2015, 36, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W. The partial least squares approach for structural equation modeling. In Modern Methods for Business Research; Marcoulides, G.A., Ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1998; pp. 295–336. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y.; Nassen, K.D. Representation of measurement error in marketing variables: Review of approaches and extension to three-facet designs. J. Econom. 1998, 89, 393–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a Silver Bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error: Algebra and Statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuzaid, A.N. The relationship between ethical leadership and organizational commitment in banking sector of Jordan. J. Econ. Adm. Sci. 2018, 34, 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torlak, N.G.; Kuzey, C.; Dinç, M.S.; Güngörmüş, A.H. Effects of ethical leadership, job satisfaction and affective commitment on the turnover intentions of accountants. J. Model. Manag. 2021, 16, 413–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buch, R. Leader–member exchange as a moderator of the relationship between employee–organization exchange and affective commitment. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2015, 26, 59–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guevara Bedoya, L.M.; Sanín Posada, A.; Tobar García, L.E. Mediación del compromiso afectivo entre las prácticas de gestión humana y las conductas de ciudadanía organizacional en jefes colombianos. Cuad. Hispanoam. Psicol. 2020, 19, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Torner, C.; González-Carrasco, M.; Miranda Ayala, R.A. Ethical Leadership and Emotional Exhaustion: The Impact of Moral Intensity and Affective Commitment. Adm. Sci. 2024, 14, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halbusi, H.A.; Tehseen, S. Impact of ethical leadership on affective commitment through mediating impact of ethical climate: A Conceptual study. Durreesamin J. 2018, 4, 1–18. Available online: http://eprints.sunway.edu.my/id/eprint/885 (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- Santiago-Torner, C. Ethical climate and creativity: The moderating role of work autonomy and the mediator role of intrinsic motivation. Cuad. Gestión 2023, 23, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.E.; Treviño, L.K. Do Role Models Matter? An Investigation of Role Modeling as an Antecedent of Perceived Ethical Leadership. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 122, 587–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, R.; Shashi; Cerchione, R.; Singh, R.; Dahiya, R. Effect of ethical leadership and corporate social responsibility on firm performance: A systematic review. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 409–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, K.D.; Cullen, J.B. Continuities and Extensions of Ethical Climate Theory: A Meta-Analytic Review. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 69, 175–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simha, A.; Cullen, J.B. Ethical Climates and Their Effects on Organizational Outcomes: Implications From the Past and Prophecies for the Future. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2012, 26, 20–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, Y.C.; Andrade, J.M.; Ramírez, E. Liderazgo Transformacional y Responsabilidad Social en Asociaciones de Mujeres Cafeteras en el Sur de Colombia. Inf. Tecnológica 2019, 30, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Fearful expectations and avoidant actions as coeffects of perceived self-inefficacy. Am. Psychol. 1986, 41, 1389–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sookdawoor, O.; Grobler, A. The dynamics of ethical climate: Mediating effects of ethical leadership and workplace pressures on organisational citizenship behaviour. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2022, 9, 2128250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, R.; Volpone, S.D.; Avery, D.R.; McKay, P. You Support Diversity, But Are You Ethical? Examining the Interactive Effects of Diversity and Ethical Climate Perceptions on Turnover Intentions. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 100, 581–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teresi, M.; Pietroni, D.D.; Barattucci, M.; Giannella, V.A.; Pagliaro, S. Ethical Climate(s), Organizational Identification, and Employees’ Behavior. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guohao, L.; Pervaiz, S.; Qi, H. Workplace Friendship is a Blessing in the Exploration of Supervisor Behavioral Integrity, Affective Commitment, and Employee Proactive Behavior—An Empirical Research from Service Industries of Pakistan. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2021, 14, 1447–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Sun, J.J.; Shaffer, M.A.; Lin, C.V. High commitment work systems and employee well-being: The roles of workplace friendship and task interdependence. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2022, 61, 399–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garces, E.; Tomei, J.; Franco, C.J.; Dyner, I. Lessons from last mile electrification in Colombia: Examining the policy framework and outcomes for sustainability. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2021, 79, 102156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Torner, C. Ethical leadership and organizational commitment in the Colombian electricity sector: The importance of work self-efficacy. Tec Empres. 2025, 19, 68–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demircioglu, M.A. The Effects of Innovation Climate on Employee Job Satisfaction and Affective Commitment: Findings from Public Organizations. Rev. Public Pers. Adm. 2023, 43, 130–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meredith, C.; Moolenaar, N.; Struyve, C.; Vandecandelaere, M.; Gielen, S.; Kyndt, E. The importance of a collaborative culture for teachers’ job satisfaction and affective commitment. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2023, 38, 43–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kariri, H.D.H.; Radwan, O.A. The Influence of Psychological Capital on Individual’s Social Responsibility through the Pivotal Role of Psychological Empowerment: A Study Towards a Sustainable Workplace Environment. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekoulou, P.; Anastasopoulou, A.; Trivellas, P. Employee Performance Implications of CSR for Organizational Resilience in the Banking Industry: The Mediation Role of Psychological Empowerment. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinomona, E.; Popoola, B.A.; Imuezerua, E. The Influence of Employee Empowerment, Ethical Climate, Organisational Support and Top Management Commitment on Employee Job Satisfaction. A Case of Companies in the Gauteng Province of South Africa. J. Appl. Bus. Res. (JABR) 2016, 33, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, S. Influence of psychological empowerment on affective, normative and continuance commitment. J. Indian Bus. Res. 2011, 3, 263–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Research on intrinsic and extrinsic motivation is alive, well, and reshaping 21st-century management approaches: Brief reply to Locke and Schattke (2019). Motiv. Sci. 2019, 5, 291–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation from a self-determination theory perspective: Definitions, theory, practices, and future directions. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2020, 61, 101860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rantika, S.D.; Yustina, A.I. Effects of ethical leadership on employee well-being: The mediating role of psychological empowerment. J. Indones. Econ. Bus. 2017, 32, 121–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albasal, N.A.; Eshah, N.; Minyawi, H.E.; Albashtawy, M.; Alkhawaldeh, A. Structural and psychological empowerment and organizational commitment among staff nurses in Jordan. Nurs. Forum 2022, 57, 624–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldham, G.R.; Hackman, J.R. Relationships Between Organizational Structure and Employee Reactions: Comparing Alternative Frameworks. Adm. Sci. Q. 1981, 26, 66–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, A.M. Psychological empowerment and organizational commitment among employees in the lodging industry. J. Hum. Resour. Hosp. Tour. 2020, 19, 277–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A.M.M.; Chiu, W.M.; Fellows, R. Enhancing commitment through work empowerment. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2007, 14, 568–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafer, W.E. Ethical climate, organizational-professional conflict and organizational commitment. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2009, 22, 1087–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Torner, C.; González-Carrasco, M.; Miranda-Ayala, R. Relationship Between Ethical Climate and Burnout: A New Approach Through Work Autonomy. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Torner, C. The influence of teleworking on creative performance by employees with high academic training: The mediating role of work autonomy, self-efficacy, and creative self-efficacy. Rev. Galega Econ. 2023, 32, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasin, R. Responsible leadership and employees’ turnover intention. Explore the mediating roles of ethical climate and corporate image. J. Knowl. Manag. 2021, 25, 1760–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimiaghdam, S.; Niroumand, T. Analyzing the relationship between perceived social responsibility and employees’ affective commitment and green behaviors: Mediating role of ethical climate. Int. J. Ethics Soc. 2022, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Torner, C. Ethical Leadership and Organizational Commitment. The Unexpected Role of Intrinsic Motivation. Rev. Univ. Empresa 2023, 25, e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Torner, C. Teletrabajo y clima ético: El efecto mediador de la autonomía laboral y del compromiso organizacional. Rev. Métodos Cuantitativos Para Econ. Empresa 2023, 36, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | N | M | SD | EC | EL | PE | AC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethical climate (EC) | 11 | 54.96 | 7.06 | 0.71 | |||

| Ethical leadership (EL) | 10 | 51.60 | 8.22 | 0.55 ** | 0.83 | ||

| Psychological empowerment (PE) | 12 | 58.91 | 7.54 | 0.36 ** | 0.38 ** | 0.89 | |

| Affective commitment (AC) | 6 | 29.81 | 4.82 | 0.34 ** | 0.29 ** | 0.39 ** | 0.83 |

| Cronbach’s-Alpha | TStatistics | CReliabitily | AVE 1 | DV 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EC | 0.88 | gt 1.96 | 0.740 | 0.510 | 0.710 |

| EL | 0.92 | gt 1.96 | 0.850 | 0.690 | 0.830 |

| PE | 0.87 | gt 1.96 | 0.730 | 0.800 | 0.890 |

| AC | 0.86 | gt 1.96 | 0.860 | 0.690 | 0.830 |

| Predictors | Model 1 (AC) | Model 2 (EC) | Model 3 (AC) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | t | β | SE | t | β | SE | t | |

| EL | 0.20 ** | 0.07 | 4.84 ** | 0.59 ** | 0.05 | 7.04 ** | 0.16 ** | 0.02 | 6.34 ** |

| EC | 0.50 ** | 0.06 | 12.16 ** | ||||||

| R2 | 0.21 ** | 0.31 ** | 0.43 ** | ||||||

| F | 41.85 ** | 66.98 ** | 97.70 ** | ||||||

| Indirect effect EC of EL on AC: β = 0.05; SE = 0.02 [0.02; 0.08] | |||||||||

| Predictors | Model 1 (EC) | Model 2 (AC) | Model 3 (AC) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | t | β | SE | t | β | SE | t | |

| EL | 0.95 ** | 0.18 | 5.26 ** | 0.29 ** | 0.20 | 3.18 ** | |||

| PE | 2.18 ** | 0.61 | 3.59 ** | 0.71 ** | 0.60 | 2.17 ** | |||

| EL × PE | 0.03 ** | 0.02 | 3.08 ** | 0.02 ** | 0.01 | 2.90 ** | |||

| EC | 0.47 ** | 0.22 | 3.43 ** | ||||||

| EC × PE | 0.02 ** | 0.03 | 2.24 ** | ||||||

| R2 | 0.34 ** | 0.15 ** | 0.15 ** | ||||||

| F | 75.17 ** | 34.20 ** | 34.20 ** | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Santiago-Torner, C.; Jiménez-Pérez, Y.; Tarrats-Pons, E. Interaction Between Ethical Leadership, Affective Commitment and Social Sustainability in Transition Economies: A Model Mediated by Ethical Climate and Moderated by Psychological Empowerment in the Colombian Electricity Sector. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6068. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17136068

Santiago-Torner C, Jiménez-Pérez Y, Tarrats-Pons E. Interaction Between Ethical Leadership, Affective Commitment and Social Sustainability in Transition Economies: A Model Mediated by Ethical Climate and Moderated by Psychological Empowerment in the Colombian Electricity Sector. Sustainability. 2025; 17(13):6068. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17136068

Chicago/Turabian StyleSantiago-Torner, Carlos, Yirsa Jiménez-Pérez, and Elisenda Tarrats-Pons. 2025. "Interaction Between Ethical Leadership, Affective Commitment and Social Sustainability in Transition Economies: A Model Mediated by Ethical Climate and Moderated by Psychological Empowerment in the Colombian Electricity Sector" Sustainability 17, no. 13: 6068. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17136068

APA StyleSantiago-Torner, C., Jiménez-Pérez, Y., & Tarrats-Pons, E. (2025). Interaction Between Ethical Leadership, Affective Commitment and Social Sustainability in Transition Economies: A Model Mediated by Ethical Climate and Moderated by Psychological Empowerment in the Colombian Electricity Sector. Sustainability, 17(13), 6068. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17136068