1. Introduction

The CE now encompasses a wide range of practices, from natural resource management to eco-design, recycling, and extending the lifespan of products [

1,

2,

3]. In theory, these practices aim to reconcile environmental and socio-economic imperatives in a win–win approach in which economic development is aligned with the preservation of natural resources through source reduction and different strategies to optimize the flow of materials into circulation [

4]. However, in practice, CE is part of the competitive dynamics of ownership, in which states, companies, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and local authorities adopt their own strategies to meet divergent economic and political objectives [

5,

6,

7].

The food sector is a good example of these tensions. Due to its multidimensional [

8,

9,

10] and multisectoral nature [

11,

12,

13], it brings together political, economic, environmental, and social issues. For example, protecting agricultural land, reterritorializing the agri-food economy, and promoting social justice require integrated approaches, but these efforts are often hindered by fragmented sectoral legislation and conflicting actor priorities [

13]. This complicates the integration of CE, in which circular initiatives require close coordination along supply chains as well as efficient reverse logistics [

11,

14]. Moreover, the specificities of food products (e.g., perishability, price volatility, and dependence on coordinated logistics) further amplify these coordination challenges. Organizational dynamics therefore play an essential role in determining the feasibility and prioritization of circular initiatives, influencing whether actors collaborate effectively, compete, or remain constrained by institutional frameworks [

15,

16].

In such a context, mapping the interests, capacities, and attitudes of actors allows us to understand how organizational dynamics influence the transition to CE [

17,

18]. While recent studies have highlighted coordination challenges in circular supply chains [

19,

20], few have explored how these dynamics manifest across the different stages of complex, multi-actor systems like food chains, in which power asymmetries, regulatory roles, and constraints may differ [

16,

21]. This article contributes to the literature by applying a sector-specific and stage-sensitive lens, showing how actor dynamics shift from upstream production to midstream processing and downstream recovery. Thus, the central question explored in this article is how the dynamics between actors, including their capacities, interests, and attitudes toward CE, affect the nature of the initiatives prioritized at different stages of the food system supply chain?

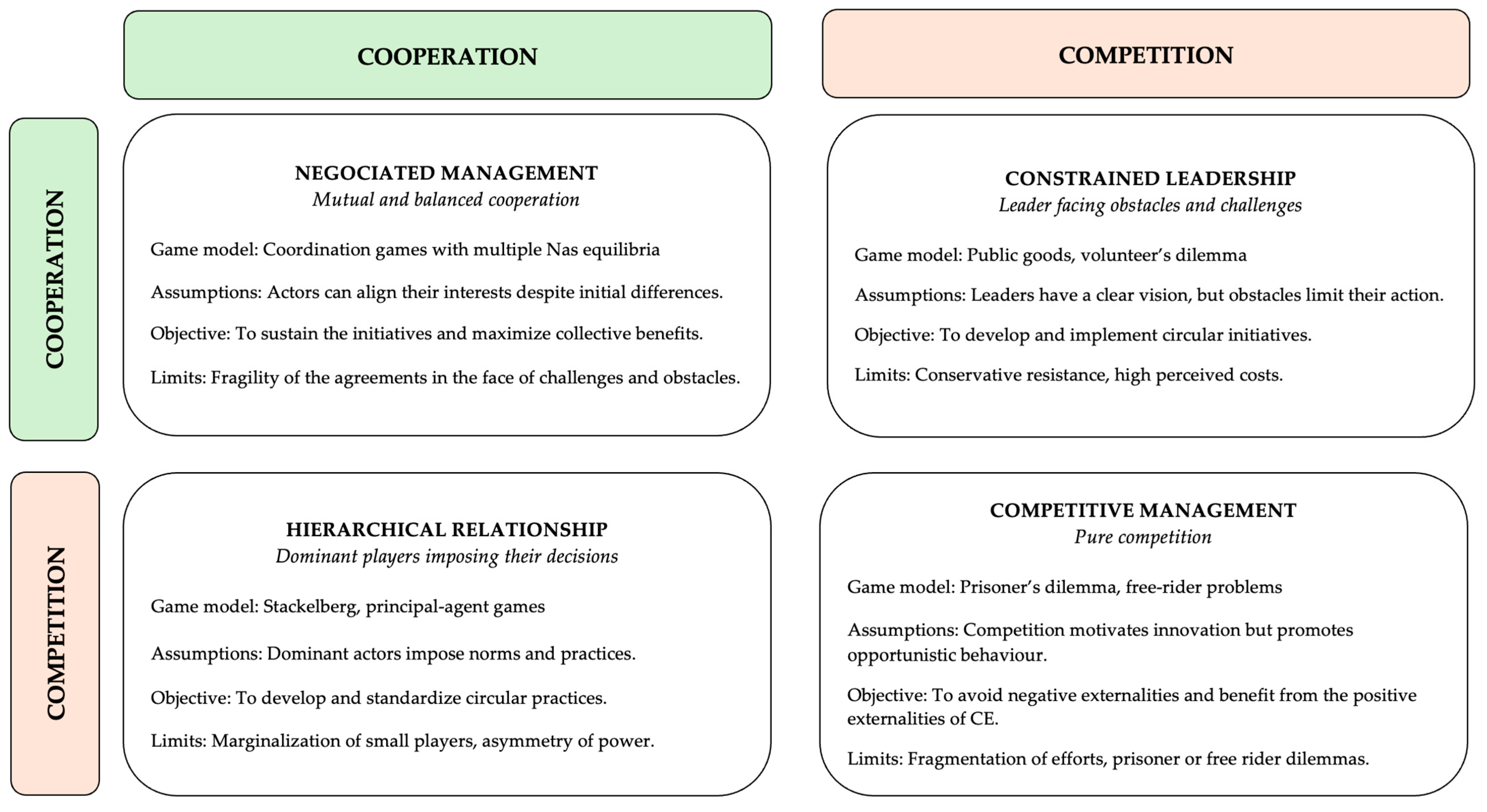

Conceptually, this study draws on game theory, building on Carrard’s typology of management dynamics [

22,

23,

24,

25]. His framework identifies four interaction types—negotiated management, constrained leadership, hierarchical relationships, and competitive management—that each offer insight into the strategic interactions between actors, the conditions required for cooperation, and the barriers posed by power asymmetries and externalities. Negotiated management refers to balanced collaborations in which compromises help maximize collective benefits. Constrained leadership captures tensions when innovative leaders encounter institutional or cultural resistance. Hierarchical relationships reflect asymmetrical power dynamics, in which dominant actors impose strategic orientations. Competitive management is characterized by rivalry, opportunistic behaviour, and the prioritization of short-term economic gains.

Empirically, these dynamics are explored through a case study of Saint-Hyacinthe, a mid-sized Canadian city located in the Montérégie region of the province of Québec, which has a population of 57,239 [

26]. Recognized as a hub in the agri-food sector in Québec and designated as an agri-food technopole, Saint-Hyacinthe benefits from a diversified network of related players. In addition, the Montérégie region has recently launched a formal transition toward CE by adopting a dedicated roadmap, further reinforcing the relevance of this territory for analysing circular dynamics. Based on two collaborative workshops involving community-based, institutional, and industrial actors, we compiled 244 entries across 12 participatory boards. These data were used to assess cooperation and competition, actor interests, attitudes toward circular initiatives, and implementation capacities.

Our results reveal that management dynamics differ across the various stages of the food system’s supply chain. Notably, the most widely supported CE initiatives are not always those with the greatest transformative potential. Instead, they tend to align with the dominant interests and capacities of key actors. Strategies that offer immediate benefits to influential players are typically favoured, whereas initiatives requiring broad cooperation or substantial upfront investment often struggle to gain traction—especially in the absence of strong incentives or adaptable implementation mechanisms.

The remainder of this article is organized as follows.

Section 2 outlines the conceptual framework, drawing on game theory to analyse strategic interactions in CE contexts.

Section 3 describes the case study and the methodological approach, including the collaborative workshops conducted with a range of stakeholders.

Section 4 presents the empirical results, detailing how cooperation, competition, hierarchy, and constrained leadership shape the adoption of circular strategies at the upstream, midstream, and downstream stages of the food supply chain.

Section 5 discusses the main implications of these findings, both theoretical and policy oriented. The conclusion summarizes the study’s key contributions, acknowledges its limitations, and suggests directions for future research, particularly regarding the evolution of inter-organizational dynamics over time.

4. Results

Results are organized into three sections corresponding to the stages of the food value chain.

Section 4.1 analyses upstream strategies, including sustainable agriculture, optimizing operations, meal planning, food preservation, choosing low-impact inputs, and clarifying expiration dates.

Section 4.2 examines strategies in the middle of the chain, focusing on the redistribution of surplus food (donations, resales) and the logistical optimization of unsold food (better preservation, reuse of leftovers, management of expiry dates, processing of downgraded food, and recovery of by-products).

Section 4.3 deals with downstream strategies, addressing the recovery and recovery of residual organic matter through composting (residential, community, and industrial) and anaerobic digestion.

Based on the analysis tables and participant discussions, the main findings for each stage highlight distinct dynamics, interests, attitudes, and capacities toward circular economy strategies.

4.1. Rethinking Production and Consumption: Tensions and Limits of Upstream Collaborations

First, strategies aimed at optimizing operations, preserving food, and clarifying expiry dates are widely adopted by distribution chains and receive some support from financial institutions. Participants noted that these initiatives are generally implemented without major resistance as they do not require significant changes to existing practices. Community and government actors expressed strong support for these strategies, viewing them as tangible means to reduce food waste and enhance food security.

Second, there is only moderate to marginal interest in more transformative strategies, such as sustainable agriculture, meal planning, and the use of low-impact inputs. According to

Table 3 and

Table 4 on actors’ attitudes and capacities, these initiatives are often merely tolerated or even rejected by certain stakeholders—particularly distribution chains and financial institutions—who view them as less profitable in the short term. Meal planning in particular is not yet perceived by the financial sector as an economically viable approach. On the production side, discussions revealed various challenges to adopting more sustainable practices. While some producers have begun implementing environmentally friendly measures, many remain reluctant due to workload pressures, regulatory constraints, and climate uncertainty.

Third, participants highlighted a general preference for initiatives focused on logistical optimization rather than those requiring deeper changes in production or consumption models. Many emphasized that financial institutions tend to prioritize actions with immediate economic returns, whereas government and community actors are more likely to promote long-term sustainability goals (

Table 5). Several participants also pointed out that siloed approaches among government bodies and economic institutions hinder the implementation of integrated, cross-cutting strategies (

Table 6).

4.2. Optimization and Redistribution: Logistical Challenges and Power Asymmetries in the Middle of the Chain

First, regarding interests (

Table 7), food donations and the resale of surplus at reduced prices were the strategies that generated the most discussion. Several participants viewed these initiatives as win–win solutions, enabling distributors to reduce losses while enhancing their social image and allowing community organizations to access food supplies. However, participants noted differences between large distributors and smaller retailers: while supermarkets are increasingly implementing structured recovery systems, small shops—particularly in more remote areas—often manage unsold goods less consistently, with food still being discarded. Legal constraints related to expiry dates were reported as limiting certain initiatives, especially in processing and distribution facilities.

Second, in terms of dynamics (

Table 8), participants emphasized that, although surplus redistribution is often portrayed as collaborative, distribution chains frequently impose specific requirements regarding volumes, timelines, and food quality. Some noted that community organizations are required to adapt to conditions set by distributors rather than establish their own supply systems. A lack of transport infrastructure and storage capacity was also cited as a major barrier preventing these organizations from fully benefiting from available surplus.

Third, regarding attitudes and capacities (

Table 9 and

Table 10), participants observed that distribution chains tend to favour initiatives that reinforce their competitiveness and corporate social responsibility while maintaining control over redistribution channels. In contrast, community-based actors face structural limitations—including insufficient funding, restrictive regulations, and logistical hurdles—that hinder their ability to absorb and redistribute surplus effectively. The tables also indicate that financial institutions and some economic stakeholders remain largely disengaged from these initiatives.

4.3. Closing the Loop: Waste Recovery and the Delicate Balance of Circular Flows

First, downstream relational dynamics (

Table 11 and

Table 12) are characterized by partial complementarity between industrial actors, public institutions, and agricultural producers. Participants noted that food producers and processors supply organic waste, while innovation and technology actors provide recovery solutions. However, discussions revealed that infrastructure is not always sufficient to ensure an efficient flow of organic matter to treatment facilities. Several participants emphasized that producers and distributors remain hesitant to engage fully in these recovery processes, citing logistical costs and the complexity of existing systems.

Second, attitudes and capacities (

Table 13 and

Table 14) vary significantly depending on economic and logistical constraints. The tables show strong support from public institutions and technological innovators for composting and anaerobic digestion, yet producers and community-based actors face substantial operational barriers. Participants highlighted challenges such as high infrastructure costs, limited access to municipal facilities (e.g., composting bins), and restrictive regulations that hinder broader adoption. Some noted that agri-food and distribution companies tend to tolerate these recovery strategies rather than actively prioritize them, viewing their implementation as an added burden with limited direct benefits.

Third, moderate competitive dynamics emerge when upstream optimization strategies reduce the availability of organic waste, thereby threatening the viability of downstream recovery systems. Participants pointed out that waste reduction at the source or its diversion to alternative uses (e.g., animal feed) can jeopardize the functioning of composting and biomethanization facilities, creating operational challenges for actors responsible for managing residual flows.

5. Discussion

These results, which highlight an uneven emphasis on CE initiatives across different stages of the supply chain as well as varying attitudes among actors, can be interpreted through the lens of game theory.

Table 15 summarizes the management dynamics and strategic tensions identified throughout the workshops, which are discussed in the following section.

5.1. Influence of Negotiated Management

In the case of Saint-Hyacinthe, negotiated management was observed across all stages of the food supply chain, though it took different forms. Upstream, it emerged through collaborations between community-based organizations, government bodies, and agricultural actors around logistics optimization, food preservation, and more sustainable farming practices. These partnerships were driven by a shared intent to gradually align interests through resource pooling and the recognition of complementarities as a foundation for collective action [

23]. However, negotiations tended to favour initiatives with immediate economic benefits over those requiring long-term commitments. More transformative efforts would demand broader behavioural shifts—particularly among consumers—which lie beyond the immediate influence of these collaborations. Despite this willingness to cooperate, such efforts remain fragile due to structural barriers (e.g., regulatory hurdles and limited institutional support) and uneven capacities among actors. For instance, participants noted that farmers were open to allowing on-farm gleaning only if food banks provided both labour and transportation—essentially requiring a turnkey solution—since producers lack time and cannot absorb additional handling costs. As highlighted in the literature, these forms of coordination require mechanisms to stabilize commitments and clarify mutual expectations in order to avoid discontinuity [

67]. However, siloed operations across government and economic institutions continue to complicate the implementation of cross-cutting strategies, as these actors often operate on different timelines and priorities—financial institutions prioritize short-term profitability, while community and public actors pursue longer-term sustainability goals.

In the middle of the supply chain, interactions between distribution chains and community organizations also reflect the logic of negotiated management. By leveraging the logistical capacities of the former and the territorial embeddedness of the latter, these arrangements seek to strike a balance between economic efficiency and social equity. However, food redistribution arrangements highlight how structural constraints can weaken genuine negotiation. Although they are often framed as collaborative, these processes are shaped by the limited negotiating power of community organizations, which face shortfalls in transportation infrastructure, storage space, and stable funding. As a result, they must often adapt to conditions set by distributors rather than engage in true bilateral negotiations. In such heterogeneous contexts, cooperation depends heavily on mutual recognition and the stability of commitments between actors [

40]. In the case of Saint-Hyacinthe, regulatory barriers, uncertain funding, and asymmetrical power dynamics undermine the development of durable partnerships—particularly where incentives remain unbalanced in favour of dominant players [

32].

Downstream, collaborations between producers, processors, and technological innovators rely on complementary technical and logistical capacities to support composting and anaerobic digestion. However, the broader rollout of these initiatives is constrained by misaligned incentives, regulatory obstacles, and uncertainty around return on investment. Public institutions can serve a critical intermediary role by fostering connections, reducing perceived risks of opportunism, and building trust—an essential ingredient for cooperation in a context marked by fragmented responsibilities [

34,

40]. Still, downstream negotiated management must contend with the challenge of reconciling competing optimization goals across the system. Participants noted that producer and distributor reluctance—citing logistical costs and system complexity—illustrates how upstream efficiency gains can unintentionally undermine downstream viability. These interdependencies highlight the need for more robust negotiation frameworks capable of addressing cross-stage impacts and aligning system-wide incentives.

5.2. Influence of Constrained Leadership

Constrained leadership is especially characteristic of transformative initiatives that require deep structural changes and a long-term vision. Across all stages of the supply chain, constrained leadership emerges when actors seeking to advance CE innovations encounter institutional, regulatory, and economic barriers that limit their reach.

Upstream, community-based and governmental actors promote practices such as sustainable agriculture, meal planning, and the use of low-impact inputs. However, their leadership remains constrained within an environment shaped by short-term profitability logic, which discourages investment in transformative circular practices in the absence of adequate public or institutional incentives [

33]. These challenges are compounded by the complex implementation requirements that are often required for transformative initiatives. Participants noted that sustainable practices are perceived as demanding significant investments and adjustments across the value chain, creating resistance—even when environmental benefits are widely acknowledged. Producers in particular face high workloads and growing climatic uncertainties, while regulatory frameworks often fail to reflect on-the-ground operational realities. As a result, even when incentives for innovation exist, agricultural producers report being held back by regulatory obstacles, high upfront costs, and inertia in both distribution chains and the financial sector. As one participant put it, they are “piloting the plane while building it.”

In the middle of the supply chain, constraints on community leadership are further reinforced by their dependence on distributor-imposed conditions for fundamental operations, such as food redistribution. While community actors bring valuable territorial knowledge and a strong commitment to circular principles, their leadership potential is systematically undermined by structural limitations—including a lack of transportation infrastructure, insufficient storage capacity, and rigid regulatory frameworks. These barriers prevent them from fully capitalizing on available resources and opportunities. As a result, their efforts remain peripheral to the dominant logic of power, even as they are symbolically valorised within corporate social responsibility discourses [

23]. One NGO representative observed, “Even though community support is part of their mandate, the closer we get to a company’s core motivation—making profits—the less appealing virtue becomes.” Workshop participants emphasized that community initiatives are often the first to be abandoned when profitability is at risk, highlighting how dominant structures may acknowledge the value of circularity but are rarely willing to share the risk or invest in low-return efforts.

Downstream, constrained leadership is reflected in efforts to recycle organic matter through initiatives such as composting and biomethanization. Although these efforts are supported by public institutions and technology providers, they face deployment challenges due to insufficient cross-sector coordination and a lack of clear strategic alignment [

32]. Downstream leadership is also hindered by a paradox: successful upstream interventions can unintentionally undermine downstream initiatives. For example, when source reduction or alternative reuse strategies succeed, they may reduce the volume of organic waste available for composting or biomethanization, thereby limiting the operational viability of recovery infrastructure. This creates a systemic tension in which isolated leadership successes at one stage of the chain can jeopardize broader circular economy goals, underscoring the need for negotiated management approaches that account for interdependencies across sectors. In addition, the mobilization of downstream actors depends on the relevance and accessibility of public incentives, which must be tailored to the operational realities on the ground [

34]. In Saint-Hyacinthe, this dynamic is particularly visible in the limited access that community-based actors—such as collective kitchens—have to key infrastructure like the biomethanization plant. Participants reported that burdensome paperwork and stringent insurance requirements illustrate a disconnect between institutional ambitions and the everyday conditions required for implementation.

5.3. Influence of Hierarchical Relationships

As structuring power relations, hierarchical dynamics strongly shape interactions within the food value chain by concentrating control over standards, resources, and recognition mechanisms—often to the detriment of actors with limited capacity or institutional influence [

23]. Upstream, this hierarchy is particularly evident in the position of agricultural producers, who are caught between the demands of distribution chains—especially those shaped by consumer expectations—and public environmental regulations. For example, large retail chains typically purchase fruits and vegetables that meet strict cosmetic and packaging criteria. Participants noted that while producers may harvest surplus crops to reduce field losses, large portions of these can be rejected if they fail to meet retailers’ expectations in terms of size or appearance. To preserve contractual relationships, farmers are often forced to absorb the disposal costs themselves or to arrange—at their own expense—for pickup by charitable organizations or gleaning initiatives. These quality standards establish a power imbalance in which producers shoulder the financial and logistical burdens, with little to no leverage to negotiate more circular solutions for imperfect produce. This limits their ability to adopt more ambitious circular practices, even when there is interest and willingness to do so. The result is a form of strategic imbalance, in which flexibility is constrained by the dominant influence of actors both upstream and downstream from the producers’ position in the chain [

22,

42].

Hierarchical relationships are most prominent in the middle of the chain, particularly in interactions between distribution chains and community organizations. The latter must adapt to the standards, logistical practices, and requirements imposed by distributors—whether in terms of volume, timing, or the quality of redistributed food. This imbalance limits their ability to design initiatives that reflect local realities and relegates them to the role of implementers within a framework set by others [

23,

40]. For example, food donations are often organized around the storage constraints of large distributors. Participants noted that delivery slots were assigned without prior consultation, forcing community organizations to mobilize last-minute volunteers or, in some cases, discard food due to scheduling mismatches. This top-down planning structure leaves little room for negotiation, pushing community partners into reactive roles. The power imbalance is further amplified when distributors publicly promote their social or environmental initiatives while continuing to prioritize short-term profitability. As a result, hierarchical control extends beyond quality standards to encompass the dominant economic logic shaping the entire value chain. Initiatives lacking immediate financial returns often struggle to gain support, regardless of their social or environmental value. Producers, in turn, are constrained not only by distributor demands but also by a financial sector that reinforces short-term profitability, adding layers of hierarchical pressure and further limiting their agency. Game theory provides a useful lens for interpreting this dynamic as a game of authority, in which dominant actors impose rules without engaging in genuine power-sharing [

42,

43].

Downstream, hierarchical logic also manifests through passive control or relative disengagement by major agri-food and distribution companies. While initiatives such as composting and biomethanization are tolerated, they remain largely peripheral to the dominant economic logic. During the second workshop, several participants noted that large retailers and processors rarely enter into long-term supply agreements with Saint-Hyacinthe’s biomethanization plant. When they do send organic waste, it is “on a case-by-case basis, when it suits them,” making it difficult for the facility to secure the consistent tonnage required to operate at full capacity. A municipal representative added that the plant’s gate-fee revenues are heavily dependent on public and agricultural volumes, as major agri-food firms “always keep a cheaper fallback option—out-of-region landfilling or shipment to a private subsidiary.” Participants agreed that this strategic disengagement enables dominant firms to claim they “offer the option” of recovery without taking on logistical or financial risks. As a result, the municipality is left to absorb fixed operational costs and relies on ad hoc provincial subsidies to keep the facility viable. This exemplifies how hierarchical power can be exercised through inaction, maintaining a deliberate distance from operational responsibility and thereby limiting systemic transformation [

34,

41].

5.4. Influence of Competitive Management

Competitive management is especially pronounced upstream and midstream, where it shapes the strategic priorities of dominant actors. Upstream, competition among distribution chains drives a focus on short-term profitability through strategies such as logistics optimization and expiry date clarification. These priorities are further reinforced by prevailing financial logics that favour rapid returns on investment over circular initiatives with delayed benefits. As one participant observed, “When it comes to the distribution chain and the financial sector, it’s always the financial side that wins out… decisions are made more in an Excel spreadsheet than through human relationships.” This dynamic helps explain why transformative strategies—such as sustainable agriculture, meal planning, and the selection of low-impact inputs—receive only marginal to moderate interest from key players. Distribution chains and financial institutions often tolerate or dismiss these initiatives, viewing them as less immediately profitable and more complex to implement due to the required investments and adjustments across the supply chain. The competitive imperative thus creates a systemic bias against deep transformations in production and consumption practices, reinforcing a form of prisoner’s dilemma: each actor pursues what is economically rational in the short term while collectively stalling progress toward more ambitious circular solutions [

23,

33].

In the middle of the chain, competition is reflected in the management of food surplus recovery. While some initiatives are framed as collaborative, they are often appropriated by large companies seeking to strengthen their strategic positioning or enhance their brand image [

44,

45]. This logic contributes to the fragmentation of collective efforts, in which actions are driven more by visibility or marketing goals than by a commitment to systemic transformation. One local organization noted that although large grocery chains do donate food surpluses, they often impose strict conditions—such as fixed schedules or quantities—and leverage these donations for public relations purposes, highlighting their corporate social responsibility. However, they rarely adjust their internal logistics to align with the operational realities of community organizations. As a result, NGOs are left to absorb the logistical and financial burdens, while corporations reap reputational benefits. This dynamic reflects free-rider strategies [

45], in which large firms gain symbolic value from CE participation while minimizing their actual contributions and maintaining strategic flexibility. Competition between companies further exacerbates these imbalances, limiting opportunities for coordination or genuine resource sharing among actors [

25].

Downstream, competitive management surfaces more indirectly, particularly through the trade-offs between upstream waste reduction and the viability of recovery infrastructure. In Saint-Hyacinthe, some community actors involved in food waste prevention expressed concern that their success could inadvertently threaten the operational thresholds needed to sustain the biomethanization plant. When upstream waste reduction efforts or redirection toward more profitable uses (e.g., animal feed) are effective, they may reduce the volume of organic matter available for recovery, undermining the economic sustainability of downstream infrastructure. This illustrates a suboptimal coordination game, in which competitive optimization at the individual level destabilizes the broader circular economy system [

33].

5.5. Public Policy Implications

The integration of CE principles into food systems management hinges on complex interactions among collaboration, hierarchy, competition, and leadership. Carrard’s typology [

22,

23,

24,

25] reminds us that none of these dynamics is inherently beneficial or detrimental to circularity; what matters are the underlying incentives, power relations, and degrees of agency. These findings lead to three key policy implications.

First, tailored incentive mechanisms are required to mitigate power asymmetries and curb opportunistic behaviour. Conditional subsidies and incentive-based contracts can foster long-term commitments from producers, distributors, and recyclers. A system of differentiated payments could, for instance, reward demonstrable investments in CE practices, while gradually enforced regulations could compel major players to set food redistribution and loss-reduction targets.

Second, to prevent locally rational but systemically inefficient decisions, collective coordination mechanisms must be established. Public–private coalitions, territorial performance contracts, or sectoral roundtables could help align strategies—particularly in surplus redistribution and organic waste management. In cases in which some companies capture the benefits of circularity without bearing the costs, targeted (rather than punitive) regulations could be used to rebalance responsibilities.

Third, circular governance requires adaptable rules grounded in ongoing knowledge of material flows. Continuous flow monitoring by a public authority paired with real-time data analysis would allow for the early detection of systemic imbalances and timely policy adjustments. For instance, if upstream reductions in surplus food begin to threaten the feedstock supply of biomethanization infrastructure, corrective measures such as differentiated subsidies or phased obligations could be introduced.

In sum, influencing strategic behaviour in support of the circular economy calls for adaptive incentives, stronger cross-sector coordination, and flexible regulatory mechanisms. Advancing this agenda requires continued modelling of strategic interactions and systemic interdependencies to guide collective decisions toward a circular transition that is both effective and equitable for all stakeholders.

5.6. Theoretical Contributions

Our findings contribute to the analysis of organizational dynamics in the circular economy by integrating well-established dimensions—such as power asymmetries, divergent interests, and heterogeneous capacities [

21,

68,

69]—into a systemic perspective. Unlike fragmented approaches, our study adopts a holistic view of the entire circular value chain, highlighting how these variables interact and shape the implementation of strategies across different stages. It also extends the conventional use of game theory, which is often critiqued for limited predictive power due to the complexity of real-world behaviours and the assumption of perfect rationality [

16,

23,

70]. Nonetheless, our results reaffirm the value of this theoretical framework for understanding policy interactions in CE contexts [

28,

32] while emphasizing the importance of contextual variables—such as capability asymmetries, conflicting interests, and regional dynamics—in interpreting these dynamics [

71]. Future research could examine mechanisms for aligning interests in specific regional settings. Longitudinal studies tracking shifts in actors’ attitudes, capacities, and interests over time would also provide a dynamic lens to identify effective policy levers. Lastly, deeper analysis of upstream–downstream interdependencies could help anticipate the systemic ripple effects of strategic decisions.

6. Conclusions

This study examined how actor dynamics, interests, capacities, and attitudes influence the implementation of CE initiatives across different stages of the food value chain. Drawing on a typology of four interaction dynamics—negotiated management, constrained leadership, hierarchical relationships, and competitive strategies—we identified distinct configurations that either enable or hinder the success of circular practices at each stage.

Our findings show that organizational dynamics play a critical role in shaping CE implementation, with notable variations along the food supply chain. Upstream, negotiated management supports the emergence of practices such as sustainable agriculture and food preservation, though these remain fragile when confronted with short-term economic logics and hierarchical pressures that marginalize less profitable approaches. In the midstream segment, food surplus redistribution relies on negotiated arrangements between distributors and community organizations, but these are limited by logistical constraints, asymmetrical incentives, and leadership imbalances that restrict deeper collaboration. Downstream, organic waste valorisation efforts face financial and infrastructural barriers, compounded by weak alignment with upstream flows, revealing poorly coordinated interdependencies that undermine overall system efficiency.

This study therefore highlights three important conclusions for CE research: (1) the implementation of circular initiatives fundamentally depends on the type and quality of strategic interactions among actors; (2) power asymmetries, institutional barriers, and sector-specific incentives shape these interactions at least as much as economic rationality; and (3) game-theoretical reasoning, when paired with empirical analysis, provides a powerful lens to understand how circular transitions unfold within contested and evolving governance relationships.

This case study has certain limitations. Its regional focus may limit the transferability of findings, and its reliance on stakeholder perceptions may underrepresent latent dynamics or informal interactions. Nonetheless, the approach provides a useful heuristic for mapping actor configurations and interaction patterns, offering a foundation for broader comparative or longitudinal research.

Future studies could further examine how these management dynamics unfold in other sectors or governance settings, and how they evolve over time. Investigating the interdependencies across segments of the value chain would also help anticipate the ripple effects of localized decisions—an essential step toward more coherent, coordinated, and inclusive circular transitions.