Discovering the Dynamics and Impact of Motorcycle Tourism: Insights into Rural Events, Cultural Interaction, and Sustainability

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Research Background

2.1. Motorcycling: Beyond Travelling—A Culture of Freedom, Adventure, and Community

- (i)

- Motivation and experience

- (ii)

- Cultural and landscape engagement

- (iii)

- Social media and community influence

- (iv)

- Logistics and planning

2.2. Motorcycle Tourism in Rural Areas: Economic Growth, Socio-Cultural Dynamics, and Environmental Considerations

2.3. Sustainability and Cultural Interaction in Motorcycle Tourism

2.4. Gender Perspective in Motorcycle Tourism and Social Sustainability

Gender Dynamics in Motorcycle Tourism: Motivations and Cultural Transformations

2.5. Revitalising Rural Tourism: Revealing the True Spirit of Motorcycle Tourism

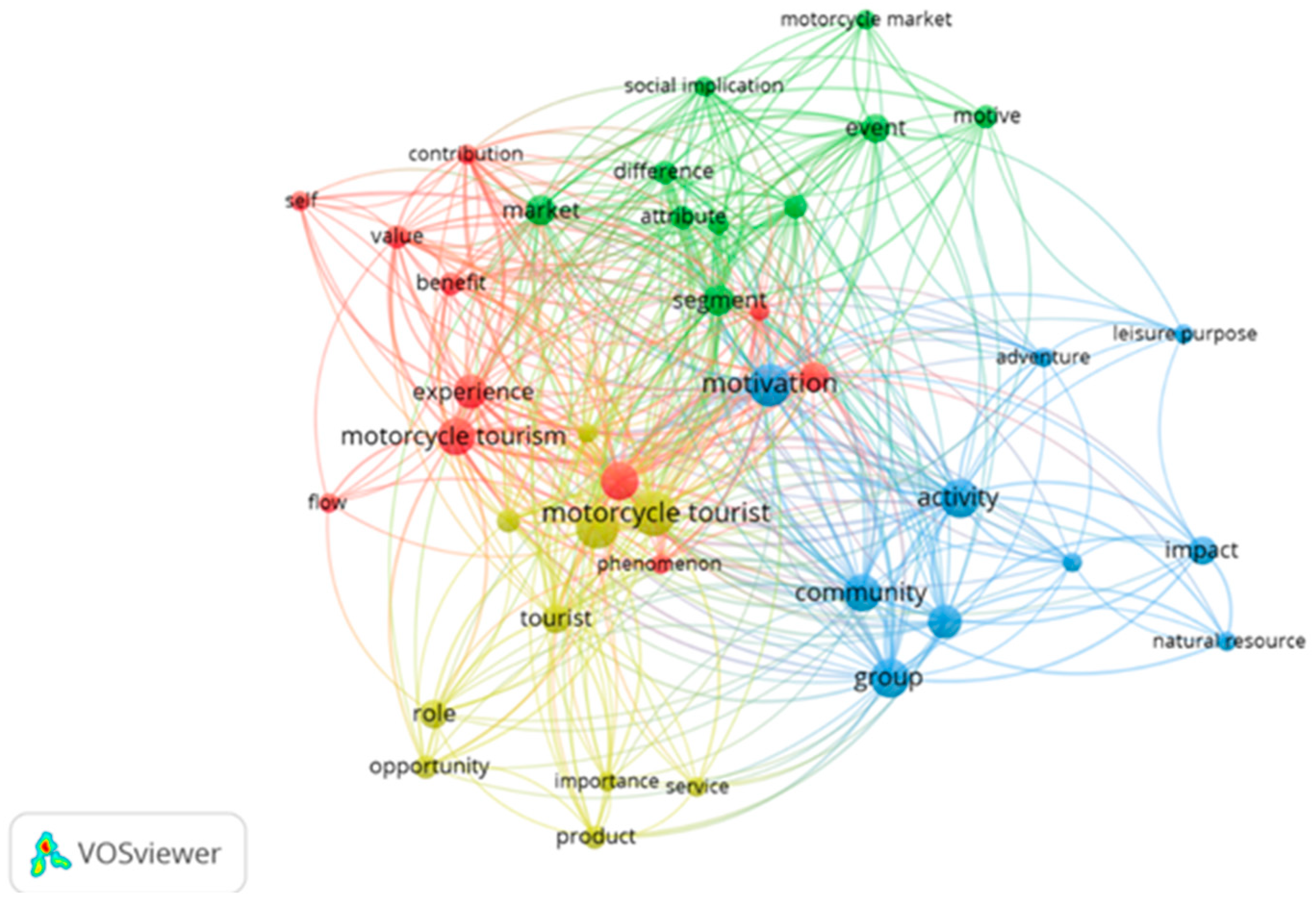

2.6. Terms That Bring Together Tourism, Motivation, Rural Areas, and Motorcycle–Clusters of Terms from the General Literature

2.7. Harnessing the Potential: Motorcycle Tourism in Rural Areas and Its Impacts on Local Economies and Culture

- (i)

- Economic impact: The economic impact of motorcycle tourism on rural tourism has been demonstrated to be a significant positive influence. The expenditure of motorcycle tourists on a variety of services and products, ranging from accommodation to local crafts, has been demonstrated to inject vital resources into rural economies [63,68].

- (ii)

- Sustainable development: The integration of local business offerings, including wineries and artisans, aligns with the sustainable development facet of motorcycle tourism. This approach has been demonstrated to support local economies whilst also helping to preserve the local culture and environment [66].

- (iii)

- Development of infrastructure and the formulation of strategic plans: These are of supreme importance. The necessity of investing in heritage restoration and infrastructure, in addition to the strategic positioning of motorcycle tourism within national tourism strategies, underscores the significance of infrastructure development and meticulous planning to enhance the experience of motorcyclists and provide support to local communities [17,66].

- (iv)

- Understanding the motivations and interests of motorcycle tourists in order to effectively attract them to a destination: It has been demonstrated that merely hosting events is insufficient to appeal to this demographic; a more profound understanding of their unique motivations and interests is necessary. This understanding is crucial to the creation of tailored experiences that meet the specific needs of motorcyclists, ensuring prolonged stays and repeat visits [24].

- (v)

- Cultural and community impact: The observation that motorcyclists often extend their stay beyond the duration of events and explore local areas indicates potential for greater cultural exchange and community engagement, leading to a deeper appreciation of rural lifestyles and traditions [66].

2.8. Research Hypotheses

3. Methodology and Methods

3.1. Analysis of the Results

3.2. Sample Profile

3.3. Exploratory Data Analysis

3.4. Binary Regression Model

3.5. Factors Influencing Destination Choice and Visitor Retention

4. Discussion of Findings

- The relationship between age and preference for the type of accommodation (present study).

- The influence of educational level on participation in local activities.

- Gender disparities regarding participation in activities and exploration of the region (the following investigation).

4.1. Confirmation of Hypotheses

4.2. Cultural Interaction, Motivations, and Inclusion

4.2.1. Cultural Interaction and Tourist Motivations

4.2.2. Cultural Authenticity and the Visitor Experience

4.2.3. Gender Perspectives and Barriers in Motorcycle Tourism

5. Theoretical and Practical Implications

6. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cudny, W.; Jolliffe, J. Car tourism–conceptualization and research advancement. Geogr. Časopis Geogr. J. 2019, 71, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scol, J. Motorcycle tourism: Renewed geographies of a marginal tourism practice. Via Tour. Rev. 2016, 9, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, A.; Bernardo, A.; Gomes, C.; Silva, F.; Peneirol, J.; Machado, S. Moto Turismo, uma cultura de aposta como produto turístico. Tour. Hosp. Int. J. 2021, 16, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peric, M.; Vitezic, V. Impact of global economic crisis on firm growth. Small Bus. Econ. 2016, 46, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getz, D.; Page, S.J. Progress and prospects for event tourism research. Tour. Manag. 2016, 52, 593–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X. Residents’ Perceptions of Small-scale Rural Events: A Dual Theory Approach. Events Tour. Rev. 2021, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Rocha, J.M.; Nunes Filho, D.M.; Ximes, R.A.S.; Neto, L.G.; dos Santos, U.M.R. Turismo de Eventos e o Desenvolvimento da Fronteira Oeste do RS: Uma análise do 3 Moto Festa Na Cidade de São Gabriel-RS. In Proceedings of the Anais do VI Seminário de Pesquisa em Turismo de Mercosul, Universidade de Caxias do Sul, Caxias do Sul, Brasil, 9–10 July 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sykes, D.M.; Kelly, K.G. Motorcycle tourism demand generators and dynamic interaction leisure. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2014, 8, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramoa, C.E.D.A.; Pires, P.D.S. O mototurismo e a sua relação com o turismo de aventura e o ecoturismo. Tur. Visão E Ação. 2019, 21, 195–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frash, R.E., Jr.; Blose, J.E. Serious leisure as a predictor of travel intentions and flow in motorcycle tourism. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2019, 44, 516–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cater, C. Motorcycle Tourism in Ceredigion; Tourism Society: Hertfordshire, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cater, C.I. Long way up: Peripheral motorcycle tourism to the North Cape. In Arctic Tourism Experiences: Production, Consumption, and Sustainability; CABI Publishing: Oxfordshire, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Scherhag, K.; Scuttari, A. Introduction to the Special Issue on “Motorcycle Tourism”. Z. Für Tour. 2022, 14, 243–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sykes, D. Cruising and Clanning: The Motorcycle Tourism Tribal Experience. In Consumer Tribes in Tourism: Contemporary Perspectives on Special-Interest Tourism; Pforr, C., Dowling, R., Volgger, M., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cater, C.I. Tourism on two wheels: Patterns of motorcycle leisure in Wales. Tour. Manag. 2017, 61, 180–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.C.; Ai, C.H.; Chang, Y.Y. What drives experiential sharing intentions towards motorcycle touring? The case of Taiwan. J. China Tour. Res. 2021, 17, 90–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Hurtado, J.M.; Oliva-López, F.; Berbel-Pineda, J.M. Antecedents and outcomes of memorable tourism experiences in tourism recreation: The case of motorcycle tourism. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2022, 49, 1126–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherhag, K.; Gross, S.; Sand, M. Adventures on two wheels–Comparative study of motorcycle adventure tourists in Germany, Austria and Switzerland. Z. Für Tour. 2022, 14, 303–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frash, R.E., Jr.; Blose, J.E.; Smith, W.W.; Scherhag, K. A multidisciplinary marketing profile of motorcycle tourists: Explorers escaping routine to find flow on scenic routes. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2018, 43, 432–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziakas, V. Understanding an event portfolio: The uncovering of interrelationships, synergies, and leveraging opportunities. J. Policy Res. Tour. Leis. Events 2010, 2, 144–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, A.; Lopes, S.; Santos, P. Two-wheeled tourism: Motard, a subculture of interest for tourism and hospitality in isolated areas? In Proceedings of the ATMC 2019—“Marketing for More Sustainable and Collaborative Tourism.”, Namur, Belgium, 4–7 September 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Dileep, M.R.; Pagliara, F. Drive Tourism: Cars, Motorcycles and RVs. In Transportation Systems for Tourism; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickerson, N.P.; Grau, K.; Sage, J.L.; Bermingham, C. Motorcycle Touring in Montana: A Market Analysis; Institute for Tourism and Recreation Research, University of Montana: Missoula, MT, USA, 2019; pp. 1–47. Available online: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/itrr_pubs/384 (accessed on 18 December 2024).

- Sykes, D.; Kelly, K.G. Motorcycle drive tourism leading to rural tourism opportunities. Tour. Econ. 2016, 22, 543–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gronau, W.; Große Hokamp, J. Motorcycle Tourism: The long ride towards an academic field of research—A literature review. Z. Für Tour. 2022, 14, 248–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León, Y.M. The impact of tourism on rural livelihoods in the Dominican Republic’s coastal areas. J. Dev. Stud. 2007, 43, 340–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, A.; Shaheer, I. Missing tales of motorcycle backpackers. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2024, 49, 671–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramoa, C.E.A.; Pires, P.S.; Añaña, E.S. Motorcycle tourism and nature: An analysis of motorcyclists motivations to travel. Leis. Stud. 2021, 40, 407–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, L. Tourism and leisure motorcycle riding. In Drive Tourism; Routledge: London, UK, 2010; pp. 160–172. [Google Scholar]

- UNWTO. Sustainable Development of Tourism, Definition. 2018. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/sustainable-development (accessed on 4 September 2024).

- Butler, R.W. Sustainable tourism: A state-of-the-art review. Tour. Geogr. 1999, 1, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gronau, W.; Hokamp, J.G.; Scherhag, K. Motorcycle Tourism and Sustainability. In Niche Tourism and Sustainability: Perspectives, Practices and Prospects; CABI: Oxfordshire, UK, 2025; pp. 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chylińska, D.; Kołodziejczyk, K. Wounded landscape: Environmental and social consequences of (illegal) motor tourism in forests on the example of Worek Okrzeszyna (the Central Sudetes on the Polish-Czech borderland). Quaest. Geogr. 2023, 42, 121–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, S.P.; de Almeida, C.R.; Pintassilgo, P.; Raimundo, R. Sustainable Drive Tourism Routes: A Systematic Literature Review. Soc. Sci. 2022, 11, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raul, G.A.D.; Gandy, G.M.S.; Briston, Y.S.I.; Willy, P.C.J. Proposal for the Implementation of Electric Motorcycle Taxis for Sustainable Urban Transportation in Districts of Peru. E3S Web Conf. 2024, 566, 04004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, S. Impact of tourism sustainability on regional development: A systematic literature review. J. Policy Res. Tour. Leis. Events 2024, 16, 290–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojović, P.; Vujko, A.; Knežević, M.; Bojović, R. Sustainable approach to the development of the tourism sector in the conditions of global challenges. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkissoon, H.; Uysal, M.S. Authenticity as a value co-creator of tourism experiences. In Creating Experience Value in Tourism; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 2018; pp. 98–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, G. Creativity and tourism: The state of the art. Ann. Tour. Res. 2011, 38, 1225–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Institute for Gender Equality. Gender Equality Index. Available online: https://eige.europa.eu/ (accessed on 8 September 2024).

- Pritchard, A.; Morgan, N. De-centring tourism’s intellectual universe or the dialectic between change and tradition. In The Critical Turn in Tourism Studies; Ateljevic, I., Pritchard, A., Morgan, N., Eds.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2007; pp. 12–28. [Google Scholar]

- Miyake, E. The Gendered Motorcycle: Representations in Society, Media and Popular Culture; Bloomsbury Publishing: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Maslow, A.H. Motivation and Personality, 3rd ed.; Pearson Education: Delhi, India, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Sabat, R. Imagens de gêneros e produção de cultura. In Gênero em Discursos da Mídia; Mulheres: Florianópolis, Brazil, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Schouten, J.W.; McAlexander, J.H. Subcultures of consumption: An ethnography of the new bikers. J. Consum. Res. 1995, 22, 43–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terry, A.; Maddrell, A.; Gale, T.; Arlidge, S. Specators’ negotiations of risk, masculinity and performative mobilities at the TT races. Mobilities 2015, 10, 628–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burbano-Valente, J.; Gafaro-Barrera, M.E.; Torres-Quintero, A.P.; Dominguez-Torres, M.T. Masculinities in transit: The voices of motorcyclists. Masculinities Soc. Change 2019, 8, 145–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borstlap, H.; Saayman, M. Is there difference between men and women motorcyclists? Acta Commer. 2018, 18, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, P.D.S. O Processo de Identificação dos Membros de Tribos Urbanas: O Caso do Grupo de Motociclismo da Harley-Davidson. Doctoral Dissertation, Fundação Getúlio Vargas, Escola de Administração de Empresas de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mesquita, M.E.A. Territórios e territorialidades urbanas em Goiânia: As tribos dos moto clubes. Bol. Goiano Geogr. 2008, 27, 125–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Reilly, K.H.; Wang, S.M.; Crossa, A. Gender disparities in New York City bike share usage. Int. J. Sustain. Transp. 2022, 16, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romy, A.; Dewan, M. The Bikerni: An ethnographic study on women motorcyclists in modern India. J. Tour. Cult. Change 2021, 19, 868–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.M.; Hespanhol, R.A.D.M. Discussão sobre comunidade e características das comunidades rurais no município de Catalão (GO). Soc. Nat. 2016, 28, 361–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Heide, T.; Scuttari, A. Holiday Preferences and Travel Behavior of German Motorcyclists. A Cluster Analysis. Z. Für Tour. 2022, 14, 284–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, W.E. Pseudo-Deviance and The “New Biker” Subculture: Hogs, Blogs, Leathers, and Lattes. Deviant Behav. 2008, 30, 89–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anico, M.; Peralta, E. Patrimónios e Identidades: Ficções Contemporâneas; Celta: Oeiras, Portugal, 2006; pp. 15–20. [Google Scholar]

- Bernardi, B. Introdução aos Estudos Etno-Antropológicos, 70th ed.; Edições: Lisboa, Portugal, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Coll, A.N. Propostas Para Uma Diversidade Cultural Intercultural na Era da Globalização; Instituto Pólis: São Paulo, Brazil, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang, X.; Hou, X.; Feng, Z.; Lin, Z.; Li, J. Subjective norms, attitudes, and intentions of AR technology use in tourism experience: The moderating effect of millennials. Leis. Stud. 2021, 40, 392–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, D.M.; Gagne, P.; Orend, A. Commodification and popular imagery of the biker in American culture. J. Pop. Cult. 2010, 43, 942–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodmann, T. Riding a straight line between the wild one and wild hogs. Int. J. Motorcycle Stud. 2014, 10. Available online: http://ijms.nova.edu/Spring2014/IJMS_Artcl.Goodmann.html (accessed on 30 November 2024).

- Artal-Tur, A.; Briones-Peñalver, A.J.; Bernal-Conesa, J.A.; Martínez-Salgado, O. Rural community tourism and sustainable advantages in Nicaragua. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 2232–2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Khan, S.U.; Khan, S.; Khan, I.U.; Mehmood, S. Greening gateways: Navigating tourists pro-environmental behavior through norms and emotions. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provetti, R. A caminho do Céu, uma Viagem de Moto pelo Altiplano Andino; Nova Letra Gráfica e Editora: Em Blumenau, Brazil, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. VOSviwer Manual Version 1. 6.10, CWTS Meaningful Metrics; Leiden Universiteit: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 1–53. Available online: https://www.vosviewer.com/documentation/Manual_VOSviewer_1.6.10.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2024).

- Sukanya, P. Women and Motorcycling: Participation in macho recreation. In Gender and Media: Significant Sociological Trends in India; Coudhuri, S., Basu, C., Eds.; Caste, Netaji Subhas Open University: Kolkata, India, 2017; pp. 123–135. [Google Scholar]

- Epure, C.E. Femininity at the helm of a gendered motorcycle world what stands between a woman and a motorcycle? Rev. Univ. Sociol. 2022, 18, 49–56. [Google Scholar]

- Sykes, D.M.; Kelly, K.G.; Ireland, B.N. Mapping the study of motorcycle tourism: Impacts and opportunities. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Tourism and Events: Opportunities, Impacts and Change 2012, Belfast, North Ireland, 20–22 June 2012; pp. 20–22. [Google Scholar]

- Jonker, J.; Pennink, B. The Essence of Research Methodology: A Concise Guide for Master and PhD Students in Management Science; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Quadri-Felitti, D.; Sykes, D.; Chen, F. Is motorcycle tourism ready to rev up in Pennsylvania? An exploratory study of suppliers’ business attitudes of motorcycle tourism. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2018, 13, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easterby-Smith, M.; Jaspersen, L.J.; Thorpe, R.; Valizade, D. Management and Business Research; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Cronbach, L.J. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrica 1951, 16, 297–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marôco, J. Análise Estatística com o SPSS Statistics, v18–v27; Report: Lisboa, Portugal, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hosmer, D.W.; Lemeshow, S. Applied Logistic Regression; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Roque, A.; Almeida, J. Rural and interpretative and regenerative tourism: A new strategic vision for reaching the 21st century. In Turismo y Región: Una Mirada Global al Desarrollo Sostenible; Editorial Corporación Universitaria del Huila: Neiva, Columbia, 2023; pp. 46–56. [Google Scholar]

- Abreu, L.A.D.; Walkowski, M.D.C.; Perinotto, A.R.C.; Fonseca, J.F.D. Community-Based Tourism and Best Practices with the Sustainable Development Goals. Adm. Sci. 2024, 14, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardo, E.; Abranja, N. Ensaio Científico sobre Abordagens Retrospetivas da Autenticidade do Turismo e das Relações entre Comunidades. Tour. Hosp. Int. J. 2024, 23, 72–101. [Google Scholar]

- Kastenholz, E.; Carneiro, M.J.; Eusébio, C.; Figueiredo, E. Host–guest relationships in rural tourism: Evidence from two Portuguese villages. Anatolia 2013, 24, 367–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panyik, E.; Costa, C.; Rátz, T. Implementing Integrated Rural Tourism: An Event-Based Approach. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 1352–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, N.M. Turismo e Recursos Endógenos como Catalizadores do Desenvolvimento Local Sustentável nos Territórios de Baixa Densidade Populacional. In Turismo, Sociedade e Ambiente; Atena Editora: Ponta Grossa, Brasil, 2020; pp. 23–29. [Google Scholar]

- Joshi, S.; Panzer-Krause, S.; Zerbe, S.; Saurwein, M. Rural Tourism in Europe from a Landscape Perspective: A Systematic Review. Eur. J. Tour. Res. 2024, 36, 3616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pine, B.J.; Gilmore, J.H. Authenticity: What Consumers Really Want; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2007; p. 299. [Google Scholar]

- Lopes, S.F. Os desafios de ser mulher no cenário dos esportes de aventura: The challenges of being a woman in the adventure sports scenario. Braz. J. Health Rev. 2021, 4, 25316–25341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, F.G.N.; Dantas, A.V.S.; Santos, A.M.; da Silva, M.J.V.; Lanzarini, R. Empoderamento feminino: A experiência da mulher no Ecoturismo e no Turismo de Aventura no RN. Rev. Bras. Ecotur. 2024, 17, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunardi, R.; De Souza, M.; Perurena, F. Participação e decisão no turismo rural: Uma análise a partir da perspectiva de gênero. Rev. Tur. Análise 2015, 26, 334–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Krittayaruangroj, K.; Suriyankietkaew, S.; Hallinger, P. Research on sustainability in community-based tourism: A bibliometric review and future directions. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2023, 28, 1031–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rid, W.; Ezeuduji, I.O.; Pröbstl-Haider, U. Segmentation by motivation for rural tourism activities in The Gambia. Tour. Manag. 2014, 40, 102–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Almeida, T.C.; Emmendoerfer, M.L. Turismo de base comunitária e desenvolvimento local sustentável: Conexões e reflexões. Rev. Tur. Contemp. 2023, 11, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardiner, S.; Janowski, I.; Kwek, A. Self-identity and adventure tourism: Cross-country comparisons of youth consumers. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2023, 46, 101061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, P.S.; Shamurailatpam, S.D. Effects and Implications of Event Tourism on Sustainable Community Development: A Review. In Event Tourism and Sustainable Community Development; Springer: Singapore, 2023; pp. 31–49. [Google Scholar]

| Male Gender | Female Gender |

|---|---|

| Adventure and Thrill-seeking | Affirmation and Breaking with Stereotypes |

| Connection and Companionship | Generating links with a community |

| Freedom and Independence | The search for the Self and Personal Growth |

| Technical and Mechanical Curiosity | Proximity to Nature and the Environment |

| Characteristic | Classification | Total Sample (n = 233) | Percentage % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 73 | 31.3 |

| Male | 160 | 68.7 | |

| Age | 18–24 | 6 | 2.6 |

| 25–34 | 29 | 12.4 | |

| 34–44 | 75 | 32.2 | |

| 44–54 | 79 | 33.9 | |

| 55–64 | 36 | 15.5 | |

| Over 64 years | 8 | 3.4 | |

| Education level | Until lower secondary | 112 | 48.1 |

| Until upper secondary | 92 | 39.5 | |

| Higher education | 29 | 12.4 | |

| Employment | Higher level/specialist in intellectual and technical professions | 29 | 12.4 |

| Specialised technical | 45 | 19.3 | |

| Employee of services/trade/administrative or employee in industry or agriculture | 108 | 46.4 | |

| Other professional occupation | 28 | 12.0 | |

| Student/retired/domestic/inactive | 23 | 9.9 | |

| Type of accommodationin this activity | Local accommodation | 20 | 8.6 |

| Caravan | 14 | 6.0 | |

| Hostel | 8 | 3.4 | |

| Hotel | 36 | 15.5 | |

| Tent at the event venue | 129 | 55.4 | |

| Home family/friends | 26 | 11.2 |

| Factors and Items | Loadings by Factor | Total Variance Explained (%) | Cronbach’s Alpha by Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| F1—Cultural | 38.466 | 0.877 | |

| Cultural heritage of the region | 0.885 | ||

| Intangible heritage of the region | 0.884 | ||

| Historical heritage | 0.867 | ||

| Landscape and nature | 0.653 | ||

| Contact with the culture of the region | 0.548 | ||

| Knowing new places | 0.506 | ||

| F2—Hospitality | 11.284 | 0.617 | |

| Socialising | 0.798 | ||

| Hospitality | 0.707 | ||

| Adventure | 0.532 | ||

| Making new friendships | 0.522 | ||

| F3—Location | 8.474 | 0.671 | |

| Programme of the event | 0.832 | ||

| Location | 0.830 | ||

| F4—Climate | 8.058 | ||

| Climate | 0.843 | ||

| KMO | 0.809 | ||

| Bartlett’s test of sphericity | = 1368.459; Sig. (p-value) < 0.001 | ||

| Cronbach’s alpha total | 0.841 | ||

| Categorical Variable Codings | Parameter Coding | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | ||

| Age (j = 1) | 18–24 (D11) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 25–34 (D12) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 35–44 (D13) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 45–54 (D14) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| 55–64 (D15) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| >64 years (D16) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| What type of accommodation do you use when carrying out this activity? (j = 2) | Local accommodation (D21) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Caravan (D22) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Hostel (D23) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Hotel (D24) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Tent at the event venue (D25) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| Home family/friends (D26) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| How many times have you been to this event? (j = 3) | 1 to 3 (D31) | 0 | 0 | 0 | - | - |

| 3 to 5 (D32) | 1 | 0 | 0 | - | - | |

| 5 to 8 (D33) | 0 | 1 | 0 | - | - | |

| More than 8 (D34) | 0 | 0 | 1 | - | - | |

| How often do you perform this activity yearly? (j = 4) | 1 to 3 times (D41) | 0 | 0 | 0 | - | - |

| 3 to 5 times (D42) | 1 | 0 | 0 | - | - | |

| 5 to 8 times (D43) | 0 | 1 | 0 | - | - | |

| More than 8 times (D44) | 0 | 0 | 1 | - | - | |

| Variables in the Equation | β | S.E. | Wald | df | Sig. (p-Value) | Exp(β) (OR) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 0 | Constant | 3.475 | 0.384 | 81.972 | 1 | 0.001 | 32.286 |

| Variables in the Equation | β | S.E. | Wald | df | Sig. (p-Value) | Exp(β) (Odds Ratio) | 95% C.I. for EXP(β) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||||

| Step 1 a | Cultural (F1) | −1.096 | 0.297 | 13.646 | 1 | 0.001 | 0.334 | 0.187 | 0.598 |

| Constant | 4.282 | 0.615 | 48.525 | 1 | 0.001 | 72.405 | |||

| Step 2 b | Cultural (F1) | −0.941 | 0.294 | 10.222 | 1 | 0.001 | 0.390 | 0.219 | 0.695 |

| Type of accommodation used when carrying out this activity (D25) | 0.498 | 0.242 | 4.230 | 1 | 0.040 | 1.646 | 1.024 | 2.646 | |

| Constant | 2.259 | 1.000 | 5.102 | 1 | 0.024 | 9.578 | |||

| Hosmer and Lemeshow Test | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Step | Chi-Square | df | Sig. (p-Value) |

| 1 | 15.644 | 5 | 0.008 |

| 2 | 7.948 | 7 | 0.337 |

| Variables in the Equation | β | S.E. | Wald | df | Sig. (p-Value) | Exp(β) (Odds Ratio) | 95% C.I. for EXP(β) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||||

| Final Step | Cultural (F1) | −0.636 | 0.279 | 5.189 | 1 | 0.023 | 0.530 | 0.258 | 1.087 |

| Local accommodation (D21) | 3.204 | 1.230 | 6.785 | 1 | 0.009 | 24.640 | 1.036 | 585.921 | |

| Hostel (D23) | 3.547 | 1.026 | 11.943 | 1 | 0.001 | 34.714 | 2.468 | 488.351 | |

| Hotel (D24) | 4.370 | 0.748 | 34.130 | 1 | 0.001 | 79.050 | 11.511 | 542.877 | |

| Hosmer and Lemeshow Test | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Step | Chi-Square | df | Sig. (p-Value) |

| 1 | 9.800 | 3 | 0.020 |

| 2 | 13.453 | 7 | 0.062 |

| Model Summary | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Step | −2 Log Likelihood | Cox & Snell R Square | Nagelkerke R Square |

| 1 | 64.705 | 0.670 | 0.893 |

| 2 | 59.023 | 0.678 | 0.904 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Monteiro, A.; Lopes, S.; Do Carmo, M. Discovering the Dynamics and Impact of Motorcycle Tourism: Insights into Rural Events, Cultural Interaction, and Sustainability. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5733. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17135733

Monteiro A, Lopes S, Do Carmo M. Discovering the Dynamics and Impact of Motorcycle Tourism: Insights into Rural Events, Cultural Interaction, and Sustainability. Sustainability. 2025; 17(13):5733. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17135733

Chicago/Turabian StyleMonteiro, Anabela, Sofia Lopes, and Manuel Do Carmo. 2025. "Discovering the Dynamics and Impact of Motorcycle Tourism: Insights into Rural Events, Cultural Interaction, and Sustainability" Sustainability 17, no. 13: 5733. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17135733

APA StyleMonteiro, A., Lopes, S., & Do Carmo, M. (2025). Discovering the Dynamics and Impact of Motorcycle Tourism: Insights into Rural Events, Cultural Interaction, and Sustainability. Sustainability, 17(13), 5733. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17135733