Determinants of Entrepreneurship in Ambato, Ecuador: Statistical Predictive and Component Modeling

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Theory of Entrepreneurial Behavior

2.2. Theory of Gender Discrimination in Entrepreneurship

2.3. Human Capital Theory and Experiential Learning

2.4. Entrepreneurship Life Cycle Theory

2.5. Institutionality and Entrepreneurship

2.6. Data Mining and Decision-Making

2.7. Hypothesis

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Approach

3.2. Participants

3.3. Instrument

3.4. Structuring the Model

3.4.1. Decision Trees

- Gini Index Reduction: Similar to information gain, it measures the reduction of impurities.

- is the Gini index of the node before division.

- is the total number of samples in the node before division.

- and are the number of samples in the left and right nodes after division.

- and are the Gini indices of the left and right nodes after splitting.

3.4.2. Principal Component Analysis (PCA)—Theoretical Background

- Preprocessing in machine learning and statistical modeling;

- Exploratory analysis to identify hidden patterns or clusters in the data;

- Improving computational efficiency by reducing the number of variables to be considered.

- Covariance matrix (C)

- Eigenvectors (V) and eigenvalues (D)

3.4.3. Random Forest

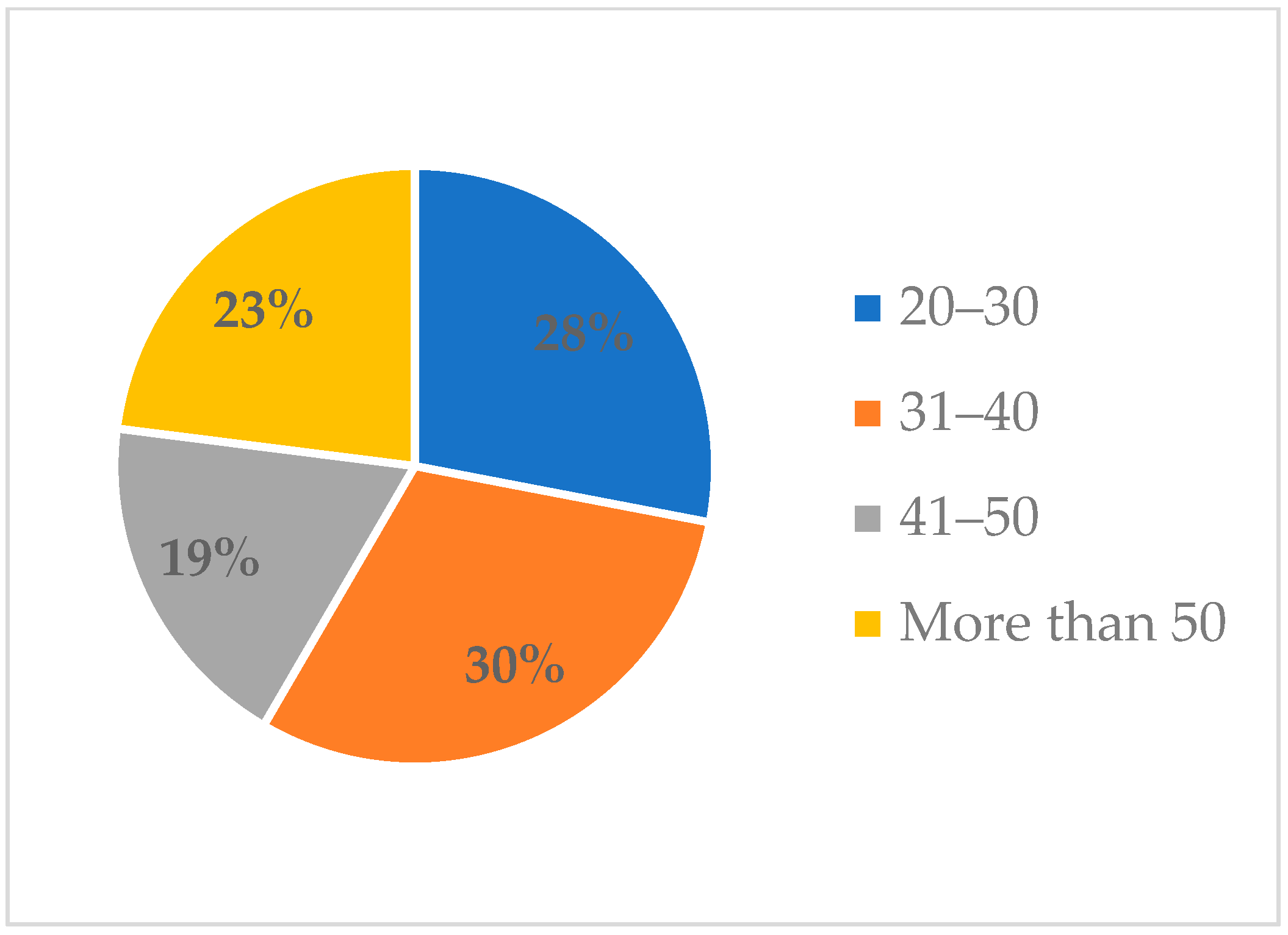

3.5. Characterization of the Sample

3.5.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.5.2. Phi Correlation

4. Results

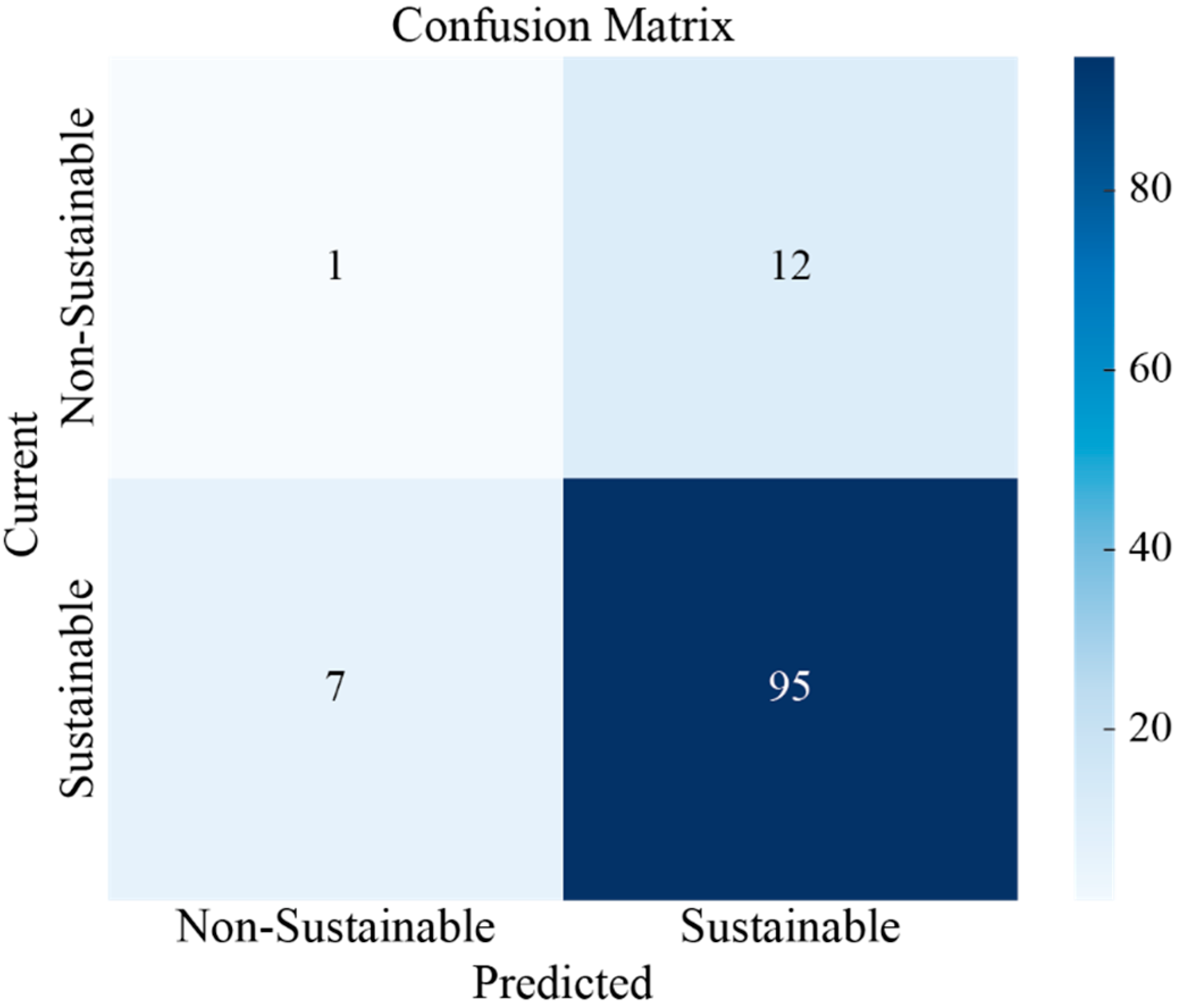

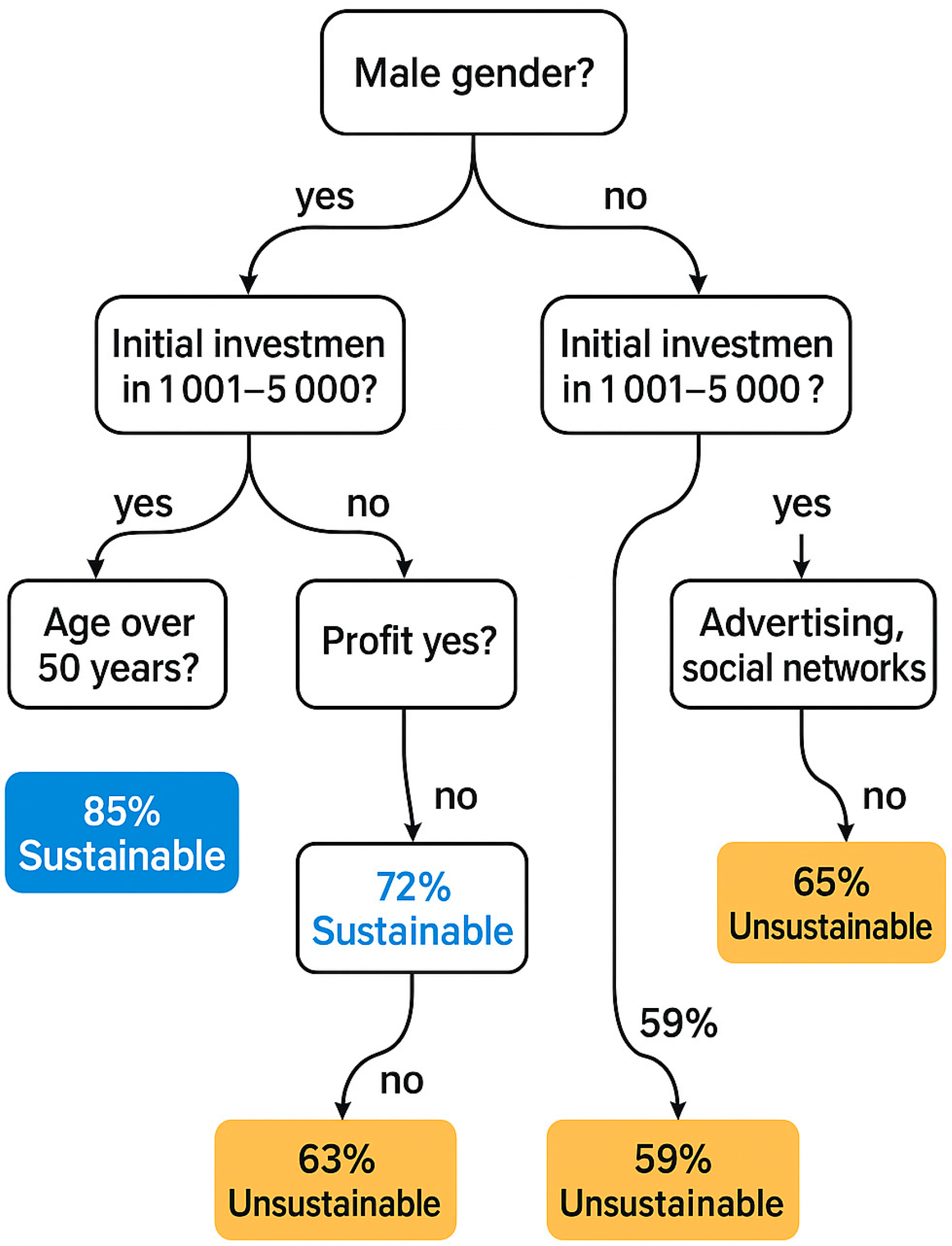

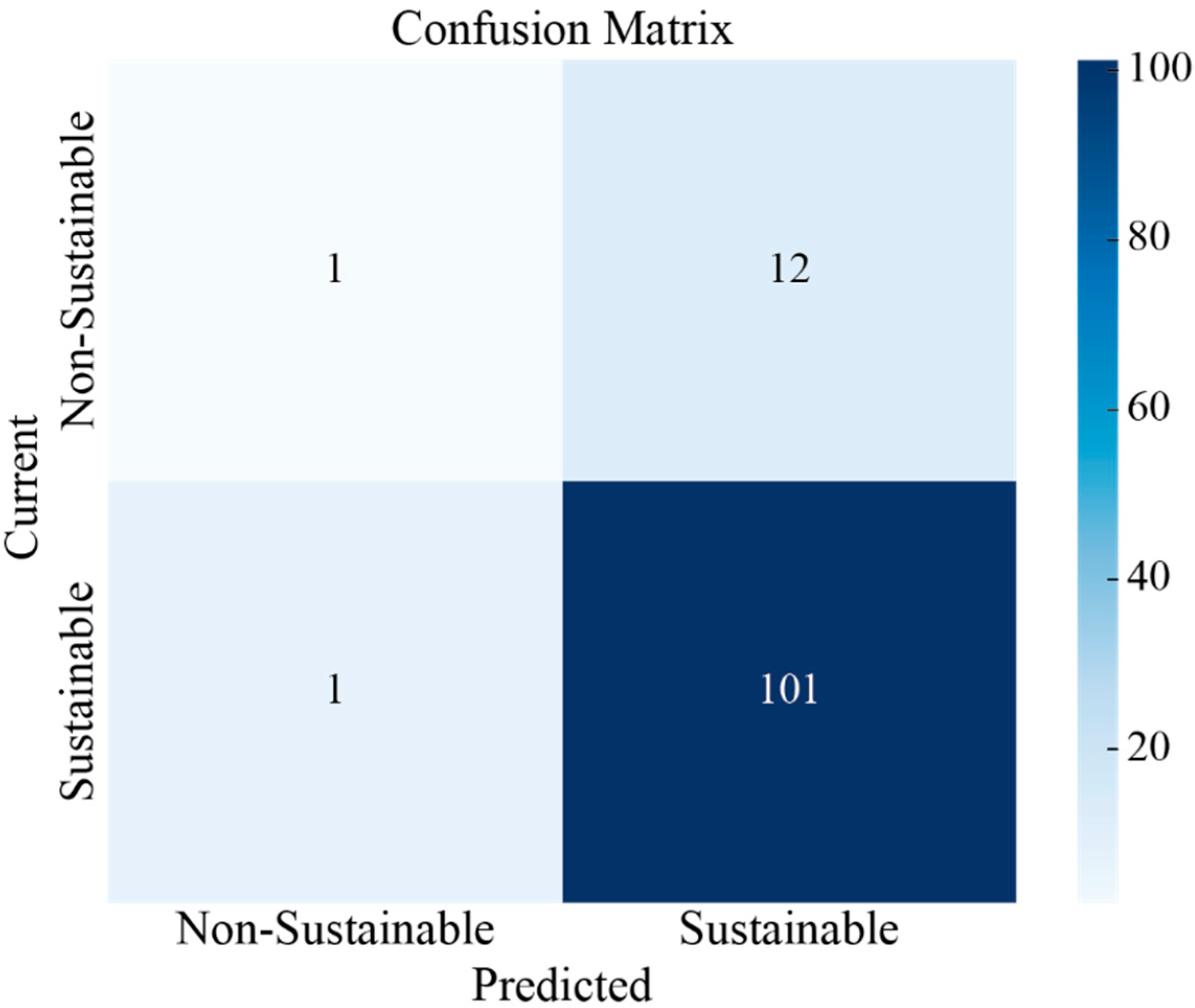

4.1. Model I. Decision Trees

- Accuracy: 0.12, indicating that only 12% of activities predicted to be unsustainable are. This case suggests a high rate of false positives in this category.

- Recall: 0.08, which means that only 8% of the actual unsustainable activities are correctly identified by the model, showing a low capacity to detect truly unsustainable cases.

- F1-score: 0.10, a combined measure of accuracy and recall, confirms the low performance of the model in this class, which may affect decision-making related to interventions or support for these endeavors.

- Accuracy: 0.89, indicating that 89% of activities classified as sustainable are indeed so.

- Recall: 0.93, which implies that the model correctly identifies 93% of all sustainable activities present in the sample.

- F1-score: 0.91 reflects a very favorable balance between accuracy and recall, showing that the model is reliable in predicting sustainable ventures in the context of Ambato.

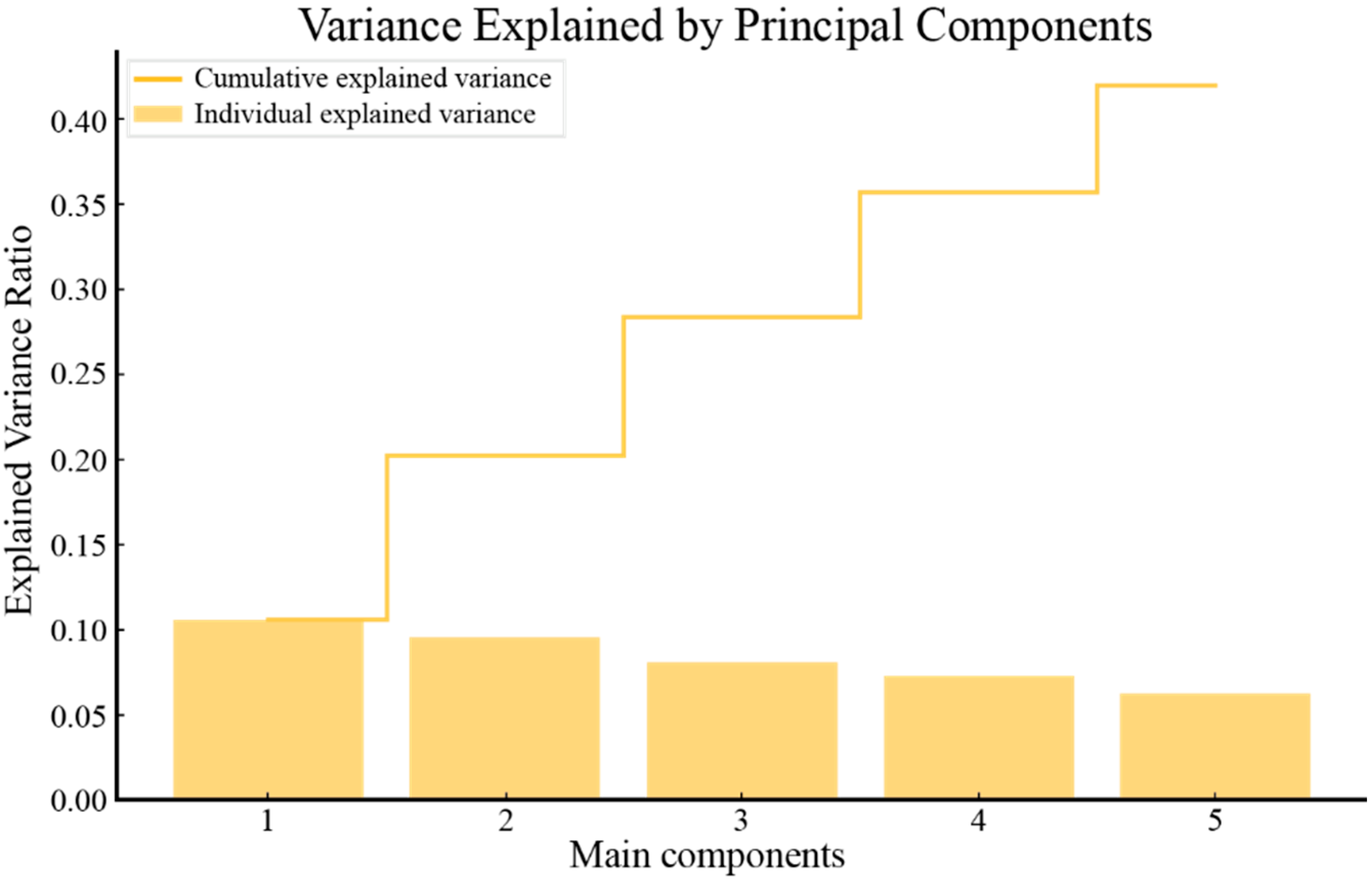

4.2. Model II. Dimensionality and Prediction

4.2.1. Principal Component Analysis (PCA)—Empirical Application

- PC1 could be related to structural factors of the business, such as formalization, access to financing, or the level of training of the entrepreneur.

- PC2 could be associated with operational or environmental variables, such as the use of technology, support networks, or market stability.

- Highlight the main dimensions that affect the sustainability of businesses;

- Reduce the number of variables without losing relevant information, which is especially useful in field studies with limited resources;

- Strengthen analysis and prediction models for better decision-making in local economic development policies.

4.2.2. Random Forest

- Age: 0.511622. This case indicates that the variable contributes strongly positively to CP1. As age increases, PC1 also tends to increase.

- Education level: −0.434221. The variable has a strong negative contribution to PC1. As the level of education increases, PC1 tends to decrease.

- Activity time: 0.299822 This variable also contributes positively to CP1, although less than age. A greater amount of time spent on the activity is associated with an increase in CP1.

- Entrepreneurship aspects: 0.200602. This variable has a positive and relatively lower contribution to PC1, indicating that a greater focus on entrepreneurship aspects is associated with an increase in PC1.

- Designing differentiated training programs according to age and educational level;

- Promoting the intergenerational exchange of experiences, where young entrepreneurs can contribute innovation and the elderly can provide stability and guidance;

- Focusing public policies on strengthening practical capacities without neglecting the incentive for formal training.

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| SRI | Servicio de Rentas Internas |

| CART | Classification and Regression Trees |

| PC1/PC2 | Main Component 1/2 |

Appendix A

- 1.

- Geographical location

- In which parish is your business located?

- Is the area where your business operates urban or rural?

- 2.

- Characteristics of the entrepreneur

- What level of formal education have you attained?

- What is your age range?

- What is your gender?

- 3.

- Characteristics of entrepreneurship

- What do you consider to be the main aspects that motivated or facilitated your venture (e.g., experience, knowledge, economic need, market opportunity)?

- What was the approximate range of initial investment in your venture?

- How long has your business been in operation?

- What media do you use to promote your business?

- Has your business generated profits (profits)?

- What kind of problems have you faced in your activity? (You can check more than one option.)

- 4.

- Funding and support

- What was the main source of financing to start your business?

- Have you received any government support for your business?

- 5.

- Sustainability and projection

- Do you consider your economic activity to be sustainable in the long term?

- In case of difficulties, have you considered suspending your economic activity?

- What do you think would be the main factor that could lead to the closure of your business (e.g., low profitability, competition, lack of support, changes in the market)?

- 6.

- Organization and development

- Does your venture have a defined business model?

- How many people do you currently have as support or staff?

- Have you received training or training related to business management?

References

- Haltiwanger, J. Entrepreneurship in the twenty-first century. Small Bus. Econ. 2021, 58, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soria-Barreto, K.; Ruiz-Campo, S.; Al-Adwan, A.S.; Zuniga-Jara, S. University Students Intention to Continue Using Online Learning Tools and Technologies: An International Comparison. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R. Exploring the Impact of Socio-Cultural Factors on Entrepreneurship Development in Emerging Markets. 2024. Available online: https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-3938479/v1 (accessed on 14 June 2025).

- Mohana Sundari, V. Analyzing Practical Tools and Scenarios for Entrepreneurial Exploration; IGI Global Scientific Publishing: Hershey, PA, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Ren, X.; Jiang, X.; Chen, G. In the context of mass entrepreneurship network embeddedness and entrepreneurial innovation performance of high-tech enterprises in Guangdong province. Manag. Decis. 2023, 62, 2532–2557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chahal, J.; Dagar, V.; Shoukat, M.H. Sustainable entrepreneurship: Examining stimulus-organism-response to the nexus of environment, education and motivation. Manag. Decis. 2025, 63, 1391–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipinski, J.; Shomali, R.Q. Navigating Adversity: Revisiting Entrepreneurial Theories in the Context of the Occupied Palestinian Territories. Adm. Sci. 2024, 14, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardini, M.G.; Khaizure, T.; Godwin, G. Exploring the Effectiveness of E-Learning in Fostering Innovation and Creative Entrepreneurship in Higher Education. Startupreneur Bus. Digit. SABDA J. 2024, 3, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, J.M.; Gomes, S.; Nogueira, E. Educational insights into digital entrepreneurship: The influence of personality and innovation attitudes. J. Innov. Entrep. 2025, 14, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajabnoor, N. Fostering environmental, social and governance-oriented startups: Accessing the moderating effect of universities on entrepreneurial leadership. Edelweiss Appl. Sci. Technol. 2024, 8, 145–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moharrak, M.; Nguyen, N.P.; Mogaji, E. Business environment and adoption of AI: Navigation for internationalization by new ventures in emerging markets. Thunderbird Int. Bus. Rev. 2024, 66, 355–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwilinski, A.; Lyulyov, O.; Pimonenko, T. The Role of Innovation Development in Advancing Green Finance. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2025, 18, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malewska, K.; Cyfert, S.; Chwiłkowska-Kubala, A.; Mierzejewska, K.; Szumowski, W. The missing link between digital transformation and business model innovation in energy SMEs: The role of digital organisational culture. Energy Policy 2024, 192, 114254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treanor, L.; Marlow, S. A nudge in the right direction? Gender-informed support by female business-incubation managers for female STEM-entrepreneurs. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2025, 37, 92–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alasmari, S.; Ali, A.J.; Khalid, J.; Chuanmin, M.; Rasheed, M.S. Servant leadership and employee creativity in Islamic context: Role of employee empowerment and knowledge sharing. Int. J. Islam. Middle East. Finance Manag. 2025. ahead of printing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defant, M. Evolutionary Basis of Gender Dynamics: Understanding Patriarchy, the Pay Gap, and the Glass Ceiling. J. Lib. Stud. 2025, 29, 10–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eklund, M.; Khalilpour, K.; Voinov, A.; Hossain, M. Community microgrids: A decision framework integrating social capital with business models for improved resiliency. Appl. Energy 2024, 367, 123458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhter, S.; Lin, C.; Guo, F.; Ahmed, K. Self-Efficacy of Students as a Mediator between Entrepreneurial Learning Engagement and EFL Learners’ Performance towards Writing Skill. J. Posthumanism 2025, 5, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoogendoorn, B.; Uhlaner, L.; van der Zwan, P.; Stephan, U. Entrepreneurship, age, and social value creation: A constraint-based individual perspective. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2024, 62, 1286–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mestwerdt, S.; Mrożewski, M.; Seckler, C. An institutional perspective on fear of failure and its effects across three entrepreneurship stages. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2024, 21, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonilla Jurado, D.; Oña Sinchiguano, B.; López Núñez, H. Measurement of technological innovation as a central axis of family business growth in the bodywork sector of the Province of Tungurahua. Rev. Lasallista Investig. 2018, 15, 271–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, T.J.; Lee, C.K.; Simmons, S.A.; Lee, J.Y. Reflection on failure and the performance of subsequent ventures: Application of reflective learning theory. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2025, 21, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Xun, H.; Xie, B.; Zeng, M.; Maharjan, D. Why and when entrepreneurs with calling perform better? The effects of calling and money motivation on entrepreneurial performance. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2025, 12, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kariv, D.; Giglio, C.; Corvello, V. Fostering Entrepreneurial intentions: Exploring the interplay of education and endogenous factors. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2025, 21, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naskar, S.T.; Hota, P.K.; Gupta, V. The efficiency paradox: How high-performance work systems interact with entrepreneurial orientation in hostile environments to impact firm performance in US firms. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2025, 21, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caputo, A.; Nguyen, V.H.A.; Delladio, S. Risk-taking, knowledge, and mindset: Unpacking the antecedents of entrepreneurial intention. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2025, 21, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, T.; Sun, L.; Wang, J.; Li, C. Team internal social capital and entrepreneurial learning: A dual-path exploration in new venture teams. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2025, 12, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Jorge, F.; Bermejo-Olivas, S.; Díaz-Garrido, E.; Soriano-Pinar, I. Success in entrepreneurship: The impact of self-esteem and entrepreneurial orientation. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2025, 21, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevi, G.; Ancillai, C.; Pascucci, F.; Palladino, R. Investigating female entrepreneurship: A micro-perspective of drivers and barriers for aspiring and experienced women entrepreneurs. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2025, 21, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez-Suárez, M.; Arilla, R.; Delbello, L. The perception of effort as a driver of gender inequality: Institutional and social insights for female entrepreneurship. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2025, 21, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Wu, Y. Doing Well and Doing Good: How Responsible Entrepreneurship Shapes Female Entrepreneurial Success. J. Bus. Ethic 2022, 178, 803–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Rosado, N.; Campos-Sánchez, A. ‘Need and opportunity’ as motivations for female entrepreneurship in Latin America. Sci. Et PRAXIS 2024, 4, 31–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, R.; Bakhshi, P.; Chandani, A.; Birau, R.; Mendon, S. Challenges faced by women entrepreneurs in South Asian countries using interpretive structural modeling. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2023, 10, 2244755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, A.; Gandhi, P.; Khare, P. Women empowerment through entrepreneurship: Case study of a social entrepreneurial intervention in rural India. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2021, 31, 1122–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, D.M.; Júnior, C.V.B.; de Almeida, M.I.S.; de Miranda, D.A. The relationship between gender policies and the creation of businesses by women. Regepe Entrep. Small Bus. J. 2023, 12, e2438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigam, N.; Shatila, K. Entrepreneurial intention among women entrepreneurs and the mediating effect of dynamic capabilities: Empirical evidence from Lebanon. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2024, 30, 916–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, B.; Shami, M.; Li, F. Gender attitudes and business venturing in low gender egalitarianism culture: A study of Egypt and Jordan. Small Bus. Econ. 2025, 64, 2153–2177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghouse, S.M.; Iii, D.B.; Alipour, K. Shaping the future Entrepreneurs: Influence of human capital and self-efficacy on entrepreneurial intentions of rural students. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2024, 22, 101035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, G. Innovative management model of human resources for entrepreneurial enterprises under the concept of sustainable development. Int. J. Innov. Sustain. Dev. 2025, 19, 367–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paunović, M.; Milovanović, V.; Štrbac, D.; Domazet, I. Intellectual capital as a driver of value creation in Serbian entrepreneurial firms. Int. J. Manpow. 2025, 46, 111–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branca, E.; Vanderstraeten, J.; Slabbinck, H.; Maes, I.M.R. The impact of entrepreneurial education on key entrepreneurial competencies: A systematic review of learning strategies and tools. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2025, 23, 101144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruthensteiner, V.; Leitner, K.-H. The role of human and financial capital in the business model design-performance relationship: Evidence from Austrian start-ups. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2025, 21, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonilla Jurado, D.M. Las tecnologías de la información y la comunicación en los ERP para la gestión empresarial. Cienc. Adm. 2024, 11, 147–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojo, M.; Bonilla Jurado, D.; Masaquiza, C. The development of new products and their impact on production: Case Study. Univ. Sociedad 2018, 10, 134–142. Available online: http://rus.ucf.edu.cu/index.php/rus (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Alzate-Alvarado, A.L.; Ribes-Giner, G.; Moya-Clemente, I. Influence of technological capability, management teams and access to finance on sustainable entrepreneurship over time. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2025, 21, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branca, E.; Intenza, M.; Doni, F. Startup entrepreneurs’ personality traits and resilience: Unveiling the interplay of prior experience. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2025, 21, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, P.L.; Ferreira, J.J.; de Oliveira, R.T. Learning before, during and after entrepreneurial failure. Bus. Process. Manag. J. 2024, 30, 1592–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korunka, C.; Kessler, A.; Frank, H.; Lueger, M. Personal characteristics, resources, and environment as predictors of business survival. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2010, 83, 1025–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonilla Jurado, D.; Noboa Larrea, G.; Ruiz Abril, K.; Cabrera Vélez, J. Academia, government and business, a perspective from the link with the community. Rev. De Investig. Enlace Univ. 2020, 19, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, D.; Sehrawat, M. Entrepreneurial Venture Funding and Growth in Industry 4.0 Era. In Principles of Entrepreneurship in the Industry 4.0 Era; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2022; pp. 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, J. Empirical research on high-growth entrepreneurship: A literature review and Latam research agenda. Manag. Res. J. Iberoam. Acad. Manag. 2022, 20, 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, R.; Ahmed, R.; Streimikiene, D.; Streimikis, J. Cross-cultural perspectives on entrepreneurship training effectiveness: Understanding the role of training duration, methodology, and expertise. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2025, 21, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazir, J.; Das, P. A systematic literature review on factors of perception impacting entrepreneurial success based on PRISMA framework. J. Innov. Entrep. 2025, 14, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalaleo Analuisa, F.R.; Chenet Zuta, M.E.; Martínez Yacelga, A.P.; Bonilla Jurado, D.M. Imagen corporativa desde la perspectiva de la comunicación empresarial: Caso Asociación Artesanal Cuero y Afines de Quisapincha. Rev. De Comun. De La Seeci 2023, 56, 265–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.; Mohamad, N.; Yusof, R. The Relationship between Financial Literacy and Entrepreneurship Spirit with Mediating Effect of Personal Financial Management. Pertanika J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2025, 33, 873–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regmi, R.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, H. Entrepreneurship strategy, natural resources management and sustainable performance: A study of an emerging market. Resour. Policy 2023, 86, 104202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.; Pandey, P.; Aggarwal, P.; Bhagwat, S.R.; MP, S. Examining the Impact of Data Mining on Decision-Making Processes. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Smart Generation Computing, Communication and Networking (SMART GENCON), Bangalore, India, 29–31 December 2023; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mydyti, H. Data Mining Approach Improving Decision-Making Competency along the Business Digital Transformation Journey: A Case Study—Home Appliances after Sales Service. SEEU Rev. 2021, 16, 45–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, M.A.; Mohamud, I.H.; Sahal, A.M.; Farah, M.A. A bibliometric analysis of academic trends in human resource management practice from 2000 to 2023. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2024, 11, 2427217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 1988. Available online: https://www.routledge.com/Statistical-Power-Analysis-for-the-Behavioral-Sciences/Cohen/p/book/9780805802832 (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Laurisz, N.; Gáspár, T.; Gałat, W.; Juhász, T. The other side of the coin: Expectations of Polish and Hungarian students on soft skills in the labour market—A futures perspective. Eur. J. Futur. Res. 2024, 12, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Díez, R.; Saiz-Santos, M.; Araujo, A. Industrial circular entrepreneurship: Supporting sustainability in the machine tool industry of the Basque Country, Spain. Manag. Res. J. Iberoam. Acad. Manag. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caliendo, M.; Kritikos, A.S.; Stier, C. The influence of start-up motivation on entrepreneurial performance. Small Bus. Econ. 2023, 61, 869–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Solís, O.; Luzuriaga-Jaramillo, A.; Bedoya-Jara, M.; Naranjo-Santamaría, J.; Bonilla-Jurado, D.; Acosta-Vargas, P. Effect of Generative Artificial Intelligence on Strategic Decision-Making in Entrepreneurial Business Initiatives: A Systematic Literature Review. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avnimelech, G.; Zelekha, Y. Religion and the gender gap in entrepreneurship. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2023, 19, 629–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavenner, K.; Crane, T.A.; Bullock, R.; Galiè, A. Intersectionality in gender and agriculture: Toward an applied research design. Gend. Technol. Dev. 2022, 26, 385–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perikleous, P.; Kafkalias, A.; Theodosiou, Z.; Barlas, P.; Christoforou, E.; Otterbacher, J.; Demartini, G.; Lanitis, A. How does the crowd impact the model? A tool for raising awareness of social bias in crowdsourced training data. In Proceedings of the 31st ACM International Conference on Information & Knowledge Management, Atlanta, GA, USA, 17–21 October 2022; pp. 4951–4954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verheul, I.; Thurik, R. Start-Up Capital: “Does Gender Matter?”. Small Bus. Econ. 2001, 16, 329–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haltiwanger, J.; Hyatt, H.R.; Spletzer, J.R. Rising Top, Falling Bottom: Industries and Rising Wage Inequality. Am. Econ. Rev. 2024, 114, 3250–3283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable 1 | Variable 2 | Φ (Phi) | Interpretation * |

|---|---|---|---|

| usefulness | sustainable activity | 0.72 | Moderate |

| usefulness | business model | 0.61 | Moderate |

| business model | training | 0.81 | Strong |

| suspend _activity | business model | 0.65 | Moderate |

| governmental support | usefulness | 0.78 | Moderate |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

López-Solís, O.; Luzuriaga-Jaramillo, A.; Bedoya-Jara, M.; Naranjo-Santamaría, J.; Negrete-Costales, O.; López-Naranjo, L.; Jara-Vásquez, E.; Acosta-Vargas, P. Determinants of Entrepreneurship in Ambato, Ecuador: Statistical Predictive and Component Modeling. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5726. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17135726

López-Solís O, Luzuriaga-Jaramillo A, Bedoya-Jara M, Naranjo-Santamaría J, Negrete-Costales O, López-Naranjo L, Jara-Vásquez E, Acosta-Vargas P. Determinants of Entrepreneurship in Ambato, Ecuador: Statistical Predictive and Component Modeling. Sustainability. 2025; 17(13):5726. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17135726

Chicago/Turabian StyleLópez-Solís, Oscar, Alberto Luzuriaga-Jaramillo, Mayra Bedoya-Jara, Joselito Naranjo-Santamaría, Omar Negrete-Costales, Lorena López-Naranjo, Ernesto Jara-Vásquez, and Patricia Acosta-Vargas. 2025. "Determinants of Entrepreneurship in Ambato, Ecuador: Statistical Predictive and Component Modeling" Sustainability 17, no. 13: 5726. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17135726

APA StyleLópez-Solís, O., Luzuriaga-Jaramillo, A., Bedoya-Jara, M., Naranjo-Santamaría, J., Negrete-Costales, O., López-Naranjo, L., Jara-Vásquez, E., & Acosta-Vargas, P. (2025). Determinants of Entrepreneurship in Ambato, Ecuador: Statistical Predictive and Component Modeling. Sustainability, 17(13), 5726. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17135726