Advancing Marine Sustainability Capacity in the Black Sea—Insights from Open Responsible Research and Innovation (ORRI)

Abstract

1. Introduction

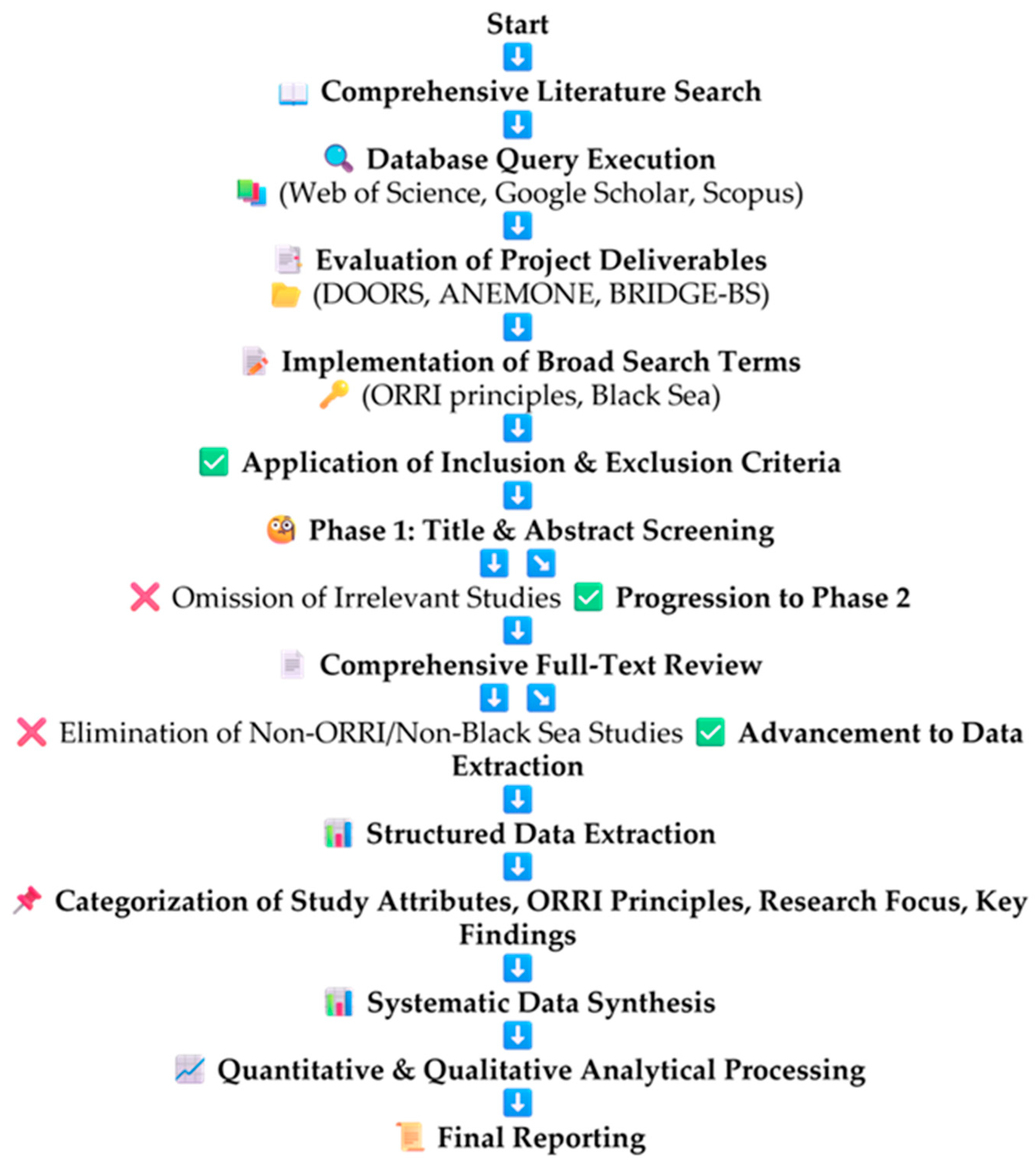

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Selection Process

- Phase 1—Title and Abstract Screening

- Phase 2—Full-Text Review

2.4. Data Extraction and Synthesis

- Study attributes: Citation details (authors, year, title).

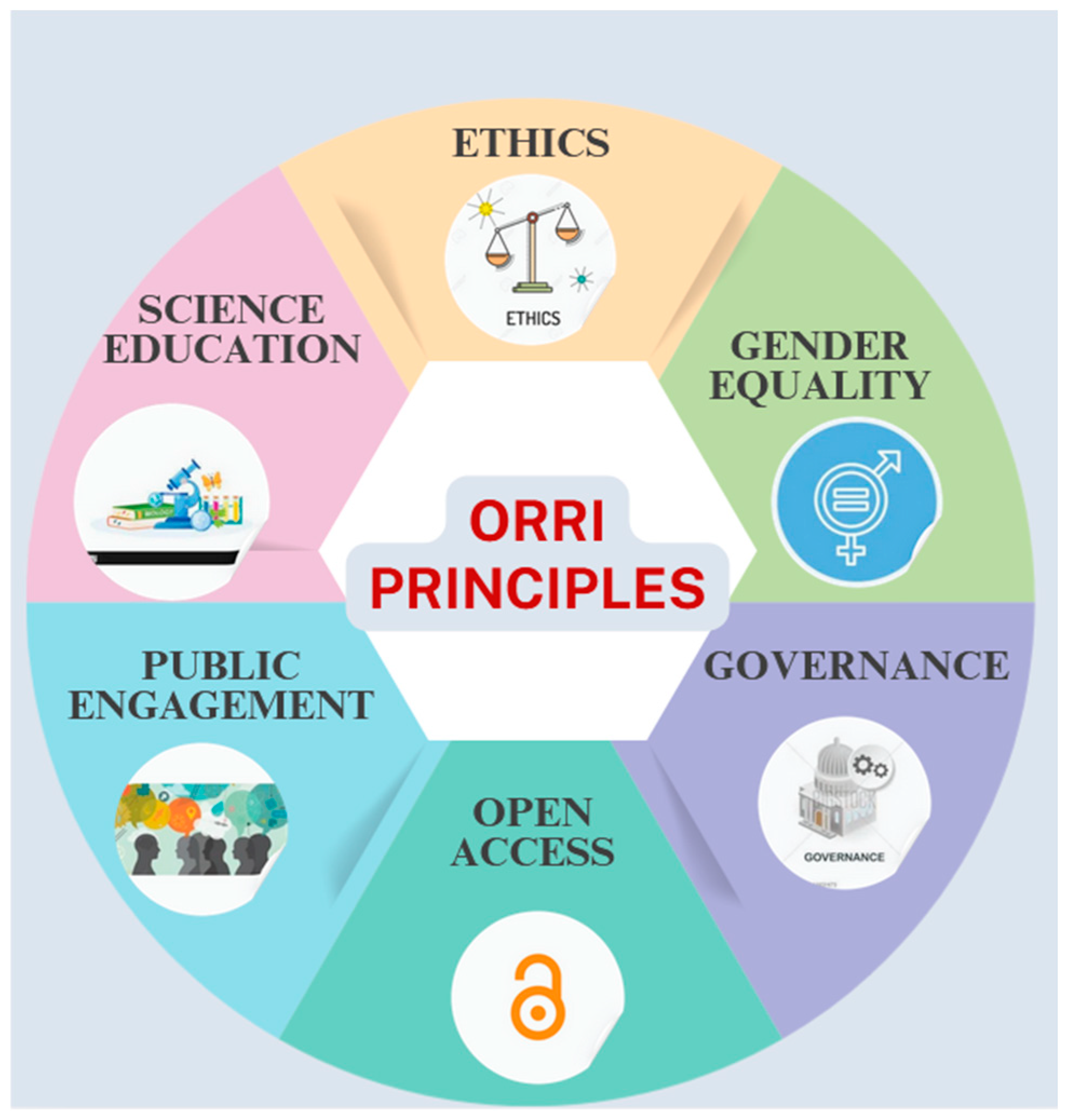

- ORRI principles addressed: Identification of relevant ORRI principles (public engagement, open access, gender equality, science education, ethics, and governance).

- Research focus: Brief description of objectives, methodologies, and geographical scope, focusing on Black Sea marine research.

- Key findings: Summary of results, conclusions, and implications for ORRI practices.

- (1)

- Quantitative synthesis: Identified trends in the adoption of ORRI principles, such as their frequency of application and integration in Black Sea research.

- (2)

- Qualitative synthesis: Analyzed specific practices, challenges, and successes, providing insight into how ORRI principles were implemented in the region, and identifying the best practices and lessons learned.

3. Results

3.1. ORRI in Black Sea

3.2. Black Sea Key Projects and Their Contributions to ORRI

4. Discussion

4.1. Advancing RRI Theory Through Regional Analysis: Lessons from ORRI in the Black Sea

4.2. A Comparative Framework for ORRI Institutionalization

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| RRI | Responsible Research and Innovation |

| ORRI | Open Responsible Research and Innovation |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| ANEMONE | Assessing the vulnerability of the Black Sea marine ecosystem to human pressures |

| DOORS | Developing Optimal and Open Research Support for the Black Sea |

| BRIDGE-BS | Advancing knowledge, delivering research, empowering citizens for sustainable and climate-neutral Black Sea |

| SoS | System of systems |

| BGA | Blue Growth Accelerator |

| SRIA | Strategic Research and Innovation Agenda |

| MARLITER | Improved online public access to environmental monitoring data and data tools for the Black Sea Basin supporting cooperation in the reduction of marine litter |

| MARINA | Marine Knowledge Sharing Platform for Federating Responsible Research and Innovation Communities |

References

- Owen, R.; Macnaghten, P.; Stilgoe, J. Responsible Research and Innovation: From Science in Society to Science for Society, with Society. Sci. Public Policy 2012, 39, 751–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Schomberg, R. A Vision of Responsible Research and Innovation. In Responsible Innovation: Managing the Responsible Emergence of Science and Innovation in Society; Owen, R., Bessant, J., Heintz, M., Eds.; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2013; pp. 51–74. [Google Scholar]

- Völker, T.; Mazzonetto, M.; Slaattelid, R.; Strand, R. Translating Tools and Indicators in Territorial RRI. Front. Res. Metr. Anal. 2023, 7, 1038970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazarko, L. Responsible Research and Innovation in Enterprises: Benefits, Barriers and the Problem of Assessment. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2020, 6, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakobsen, S.-E.; Fløysand, A.; Overton, J. Expanding the Field of Responsible Research and Innovation (RRI)—From Responsible Research to Responsible Innovation. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2019, 27, 2329–2343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Directorate-General for Research and Innovation Responsible Research and Innovation—Europe’s Ability to Respond to Societal Challenges; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2012.

- Gerber, A.; Forsberg, E.-M.; Shelley-Egan, C.; Arias, R.; Daimer, S.; Dalton, G.; Cristóbal, A.B.; Dreyer, M.; Griessler, E.; Lindner, R.; et al. Joint Declaration on Mainstreaming RRI across Horizon Europe. J. Responsible Innov. 2020, 7, 708–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hecker, S.; Haklay, M.; Bowser, A.; Makuch, Z.; Vogel, J.; Bonn, A. Citizen Science and Responsible Research and Innovation. In Citizen Science: Innovation in Open Science, Society and Policy; Hecker, S., Haklay, M., Bowser, A., Makuch, Z., Vogel, J., Bonn, A., Eds.; UCL Press: London, UK, 2018; ISBN 9781787352339. [Google Scholar]

- Sorokin, Y.I. The Black Sea: Ecology and Oceanography; Biology of Inland Waters Series; Backhuys Publishers: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bakan, G.; Büyükgüngör, H. The Black Sea. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2000, 41, 24–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaitsev, Y.P.; Alexandrov, B.G.; Berlinsky, N.A.; Zenetos, A. Seas Around Europe: The Black Sea: An Oxygen-Poor Sea. Europe’s Biodiversity: Biogeographical Regions and Seas; European Environment Agency: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Miladinova, S.; Stips, A.; Moy, D.M.; Garcia-Gorriz, E. Pathways and Mixing of the North Western River Waters in the Black Sea. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2020, 236, 106630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cîndescu, A.-C.; Petrișoaia, S.; Marin, D.; Buga, L.; Sirbu, G.; Spinu, A. The Variability of the Beach Morphology and the Evolution of the Shoreline in the Strongly Anthropized Sector of Eforie North, the Romanian Coast of the Black Sea. Cercet. Mar.-Rech. Mar. 2024, 53, 6–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turp, M.T.; An, N.; Bilgin, B.; Şimşir, G.; Orgen, B.; Kurnaz, M.L. Projected Summer Tourism Potential of the Black Sea Region. Sustainability 2023, 16, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afanasyev, A.A.; Kalognomos, S.; Lappo, A.D.; Danilova, L.V.; Konovalov, A.M. The Blue Economy and the Black Sea: Research Trends and Prospects for Scientific Cooperation in the Black Sea Region. In Innovative Trends in International Business and Sustainable Management; Springer: Singapore, 2023; pp. 519–528. [Google Scholar]

- Cozzi, S.; Ibáñez, C.; Lazar, L.; Raimbault, P.; Giani, M. Flow Regime and Nutrient-Loading Trends from the Largest South European Watersheds: Implications for the Productivity of Mediterranean and Black Sea’s Coastal Areas. Water 2019, 11, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massa, F.; Onofri, L.; Fezzardi, D. Aquaculture in the Mediterranean and the Black Sea: A Blue Growth Perspective. In Handbook on the Economics and Management of Sustainable Oceans; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ristea, E.; Bisinicu, E.; Lavric, V.; Parvulescu, O.C.; Lazar, L. A Long-Term Perspective of Seasonal Shifts in Nutrient Dynamics and Eutrophication in the Romanian Black Sea Coast. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazar, L.; Vlas, O.; Pantea, E.; Boicenco, L.; Marin, O.; Abaza, V.; Filimon, A.; Bisinicu, E. Black Sea Eutrophication Comparative Analysis of Intensity between Coastal and Offshore Waters. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisinicu, E.; Abaza, V.; Boicenco, L.; Adrian, F.; Harcota, G.-E.; Marin, O.; Oros, A.; Pantea, E.; Spinu, A.; Timofte, F.; et al. Spatial Cumulative Assessment of Impact Risk-Implementing Ecosystem-Based Management for Enhanced Sustainability and Biodiversity in the Black Sea. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazar, L.; Spanu, A.; Boicenco, L.; Oros, A.; Damir, N.; Bisinicu, E.; Abaza, V.; Filimon, A.; Harcota, G.; Marin, O.; et al. Methodology for Prioritizing Marine Environmental Pressures under Various Management Scenarios in the Black Sea. Front. Mar. Sci. 2024, 11, 1388877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazar, L.; Boicenco, L.; Pantea, E.; Timofte, F.; Vlas, O.; Bișinicu, E. Modeling Dynamic Processes in the Black Sea Pelagic Habitat—Causal Connections Between Abiotic and Biotic Factors in Two Climate Change Scenarios. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oros, A.; Coatu, V.; Damir, N.; Danilov, D.; Ristea, E. Recent Findings on the Pollution Levels in the Romanian Black Sea Ecosystem: Implications for Achieving Good Environmental Status (GES) Under the Marine Strategy Framework Directive (Directive 2008/56/EC). Sustainability 2024, 16, 9785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ristea, E.; Pârvulescu, O.C.; Lavric, V.; Oros, A. Assessment of Heavy Metal Contamination of Seawater and Sediments Along the Romanian Black Sea Coast: Spatial Distribution and Environmental Implications. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Childs, N. The Black Sea in the Shadow of War. Survival 2023, 65, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renolafitri, H.; Yolandika, C. Impact of the Russia-Ukraine War on the Environmental, Social and Economic Conditions of the Black Sea. Econ. Manag. Soc. Sci. J. 2022, 1, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesser, I.O. Global Trends, Regional Consequences: Wider Strategic Influences on the Black Sea; Xenophon Paper No. 4; International Centre for Black Sea Studies (ICBSS): Athens, Greece, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Pădureanu, M.-A.; Oneașcă, I. From Synergy to Strategy in the Black Sea Region: Assessing Opportunities and Challenges; EIR Working Papers Series; Econstor: Hamburg, Germany, 2024; p. 51. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stilgoe, J.; Owen, R.; Macnaghten, P. Developing a Framework for Responsible Innovation. Res. Policy 2013, 42, 1568–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Federation of Social Workers. Available online: https://www.ifsw.Org/New-Policy-Paper-Social-Work-and-the-United-Nations-Sustainable-Development-Goals-Sdgs/ (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- Georgeson, L.; Maslin, M. Putting the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals into Practice: A Review of Implementation, Monitoring, and Finance. Geo Geogr. Environ. 2018, 5, e00049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorooshian, S. The Sustainable Development Goals of the United Nations: A Comparative Midterm Research Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 453, 142272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jan van Eck, N.; Waltman, L. VOSviewer Manual; Univeristeit Leiden: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gheorghe, A.M.; Paiu, A.; Mirea-Cândea, M.; Paiu, R.M. Public Engagement-A Step Towards Responsible Research and Innovation. Rev. Cercet. Mar.-Rev. Rech. Mar.-Mar. Res. J. 2017, 47, 267–272. [Google Scholar]

- Albayrak, T. Cross Border Cooperation for Sustainable Environment Protection. Sci. Bull. Nav. Acad. 2021, XXIV, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbier, M.; Reitz, A.; Pabortsava, K.; Wölfl, A.-C.; Hahn, T.; Whoriskey, F. Ethical Recommendations for Ocean Observation. Adv. Geosci. 2018, 45, 343–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokos, M.; De-Bastos, E.; Realdon, G.; Wojcieszek, D.; Papathanasiou, M.; Tuddenham, P. Navigating Ocean Literacy in Europe: 10 Years of History and Future Perspectives. Mediterr. Mar. Sci. 2022, 23, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DOORS Project. Developing Optimal and Open Research Support for the Black Sea. Available online: https://www.doorsblacksea.eu/ (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Black Sea CONNECT. Strategic Research and Innovation Agenda for the Black Sea (SRIA). Available online: http://connect2blacksea.org/the-sria (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- BRIDGE-BS Project. Bridging Science, Innovation, and Policy for the Black Sea. Available online: https://bridgeblacksea.org/ (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- LitOUTer Project. Raising Public Awareness and Reducing Marine Litter for Protection of the Black Sea Ecosystem. Available online: https://litouterproject.eu/ (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- MARLITER Project. Improved Online Public Access to Environmental Monitoring Data and Data Tools for the Black Sea Basin Supporting Cooperation in the Reduction of Marine Litter. Available online: https://marliter.bsnn.org/ (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- ANEMONE Project. Assessing the Vulnerability of the Black Sea Marine Ecosystem to Human Pressures. Available online: https://www.rmri.ro/Home/Programmes.InternationalProjects.html?lang=en (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- MARINA Project. Marine Knowledge Sharing Platform for Federating Responsible Research and Innovation Communities. Available online: https://www.marina-platform.eu (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Gheorghe, A.-M.; Lungu, B.; Mihailov, P.; Yordanova, D.; Alkan, A.O.; Marin, M.C.; Alexandrov, P.A.; Palazov, A.I.; Mihailescu, M.P.; Kolarov, S.; et al. From Public Engagement to Citizen Science—Black Sea Model; Ed. Cd Press: Constanța, Romania, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Gheorghe, A.-M.; Boicenco, L.; Panayotova, M.; Denga, Y.; Atabay, H.; Ozturk, A.A.; Cândea, M.; Paiu, A.; Ionașcu, A.; Paiu, M.; et al. Marine Litter Status on Black Sea Shore Through Citizen Science; CD Press: București, Romania, 2021; ISBN 9786065285613. [Google Scholar]

- Fauville, G.; Strang, C.; Cannady, M.A.; Chen, Y.-F. Development of the International Ocean Literacy Survey: Measuring Knowledge across the World. Environ. Educ. Res. 2019, 25, 238–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lothian, S.; Haas, B. The Outliers: Stories of Success in Implementing Sustainable Development Goal 14. Ocean Soc. 2024, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanteler, D.; Bakouros, I. Enhancing Cross-Border Disaster Management in the Balkans: A Framework for Collaboration Part I. J. Innov. Entrep. 2024, 13, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, M. Governance Criteria for Effective Transboundary Biodiversity Conservation. Int. Environ. Agreem. Politics Law Econ. 2016, 16, 797–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mpofu, E.; Radinger-Peer, V.; Musakwa, W.; Penker, M.; Gugerell, K. Discourses on Landscape Governance and Transfrontier Conservation Areas: Converging, Diverging and Evolving Discourses with Geographic Contextual Nuances. Biodivers. Conserv. 2023, 32, 4597–4626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thibault, R.T.; Amaral, O.B.; Argolo, F.; Bandrowski, A.E.; Davidson, A.R.; Drude, N.I. Open Science 2.0: Towards a Truly Collaborative Research Ecosystem. PLoS Biol. 2023, 21, e3002362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latour, M.; van Laerhoven, F. A New Perspective on the Work of Boundary Organisations: Bridging Knowledge between Marine Conservation Actors in Pacific Small Island Developing States. Environ. Sci. Policy 2024, 162, 103903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinfield, S. Achieving Global Open Access: The Need for Scientific, Epistemic and Participatory Openness; Taylor and Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2024; ISBN 9781040100578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kujala, J.; Sachs, S.; Leinonen, H.; Heikkinen, A.; Laude, D. Stakeholder Engagement: Past, Present, and Future. Bus. Soc. 2022, 61, 1136–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, M.; Triantaphyllou, D. A 2020 Vision for the Black Sea Region: The Commission on the Black Sea Proposes. Southeast Eur. Black Sea Stud. 2010, 10, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ombaka, B.; Muturi, M. Importance of Ethics in Safeguarding and Ensuring High Quality Research. J. Afr. Interdiscip. Stud. 2024, 8, 89–100. Available online: https://kenyasocialscienceforum.wordpress.com/2024/06/13/ombaka-b-muturi-m-2024-importance-of-ethics-in-safeguarding-and-ensuring-high-quality-research-journal-of-african-interdisciplinary-studies-86-89-100/ (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Qassimi, N.M. Ensuring Ethical Research Practices: A Comprehensive Examination of Actions Aligned with Ethical Principles. Zenodo 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miteu, G.D. Ethics in Scientific Research: A Lens into Its Importance, History, and Future. Ann. Med. Surg. 2024, 86, 2395–2398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Campa, S.; Sanahuja, R. Gender Mainstreaming and RRI: The Double Challenge. In Ethics and Responsible Research and Innovation in Practice: The ETHNA System Project; González-Esteban, E., Feenstra, R.A., Camarinha-Matos, L.M., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; Volume 13875, pp. 188–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bührer, S.; Wroblewski, A. The Practice and Perceptions of RRI—A Gender Perspective. Eval. Program Plan. 2019, 77, 101717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, L.; Nielsen, M.W.; Schiebinger, L. A Framework for Sex, Gender, and Diversity Analysis in Research. Science 2022, 377, 1492–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rai, M.; Paul, S. Exploring Gender Justice for Attaining Equality. In Gender Equality; Leal Filho, W., Azul, A.M., Brandli, L., Lange Salvia, A., Özuyar, P.G., Wall, T., Eds.; Encyclopedia of the UN Sustainable Development Goals; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 266–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamala, K.; Kamalakar, G. Gender Equality and Human Rights: A Contemporary Analysis. Int. J. Political Sci. 2024, 10, 31–35. Available online: https://rfppl.co.in/subscription/upload_pdf/31-35-ijops-1721638418.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Clavero, S.; Galligan, Y. Delivering Gender Justice in Academia through Gender Equality Plans? Normative and Practical Challenges. Gend. Work. Organ. 2021, 28, 1115–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unterhalter, E. Global Inequality, Capabilities, Social Justice: The Millennium Development Goal for Gender Equality in Education. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2005, 25, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paredes-Frigolett, H.; Pyka, A.; Leoneti, A.B.; Nachar-Calderón, P. Governance of Responsible Research and Innovation: A Social Welfare, Psychologically Grounded Multicriteria Decision Analysis Approach. Heliyon 2025, 11, e40863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkerhoff, D.W. Accountability and Good Governance: Concepts and Issues. In International Development Governance; Huque, A.S., Zafarullah, H., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2017; pp. 269–287. [Google Scholar]

- Chanda, C.T.; Madoda, D.; Sain, Z.H.; Chisebe, S.; Chansa, C.T.; Sylvester, C. Good Governance: A Pillar to National Development. Int. J. Res. Publ. Rev. 2024, 5, 6215–6223. [Google Scholar]

- Azeem, H.M.; Sheer, A.; Umar, M. Unveiling the Power of the Right to Information: Promoting Transparency, Accountability, and Effective Governance. Al-Kashaf Res. J. Soc. Sci. 2023, 3, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Glass, L.-M.; Newig, J. Governance for Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals: How Important Are Participation, Policy Coherence, Reflexivity, Adaptation and Democratic Institutions? Earth Syst. Gov. 2019, 2, 100031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krickovic, A. “All Politics Is Regional”: Emerging Powers and the Regionalization of Global Governance. Glob. Gov. Rev. Multilater. Int. Organ. 2015, 21, 557–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Indicators for Promoting and Monitoring Responsible Research and Innovation: Report from the Expert Group on Policy Indicators for Responsible Research and Innovation; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2015.

- Aidinlis, S. The ‘Urgencies’ of Implementing an RRI Approach in EU-Funded Law Enforcement Technology Development: Between Frameworks and Practice. J. Responsible Innov. 2025, 12, 2390198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, C.; Heeks, R. Policies to Support Inclusive Innovation; Centre for Development Informatics, Institute for Development Policy and Management, SEED: Manchester, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bäckstrand, K.; Koliev, F.; Mert, A. Governing SDG Partnerships: The Role of Institutional Capacity, Inclusion, and Transparency. In Partnerships and the Sustainable Development Goals; Murphy, E., Banerjee, A., Walsh, P.P., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velikova, V.; Oral, N. Governance of the Protection of the Black Sea: A Model for Regional Cooperation. In Environmental Security in Watersheds: The Sea of Azov; Lagutov, V., Ed.; NATO Science for Peace and Security Series C: Environmental Security; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acikmese, S.A.; Triantaphyllou, D. The Black Sea Region: The Neighbourhood Too Close to, yet Still Far from the European Union. J. Balk. Near East. Stud. 2014, 16, 279–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triantaphyllou, D. The ‘Security Paradoxes’ of the Black Sea Region. Southeast Eur. Black Sea Stud. 2009, 9, 225–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, L.; Gross, T.; Hillebrand, H.; Sandberg, A.; Sayama, H. Sustainability: We Need to Focus on Overall System Outcomes Rather than Simplistic Targets. People Nat. 2024, 6, 391–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monsonís-Payá, I.; Iñigo, E.A.; Blok, V. Participation in Monitoring and Evaluation for RRI: A Review of Procedural Approaches Developing Monitoring and Evaluation Mechanisms. J. Responsible Innov. 2023, 10, 2233234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuijff, M.; Dijkstra, A.M. Practices of Responsible Research and Innovation: A Review. Sci. Eng. Ethics 2020, 26, 533–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, D. Open-Access Publishing Fees Deter Researchers in the Global South. Nature 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, A.T.; Shinwari, Z.K.; Islam, A. Fostering Openness in Open Science: An Ethical Discussion of Risks and Benefits. Front. Political Sci. 2022, 4, 930574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, A.D.; Myers, T.C.; Steury, T.D.; Krzton, A.; Yanes, J.; Barber, A.; Barry, J.; Barua, S.; Eaton, K.; Gosavi, D.; et al. Does It Pay to Pay? A Comparison of the Benefits of Open-Access Publishing across Various Sub-Fields in Biology. PeerJ 2024, 12, e16824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armeni, K.; Brinkman, L.; Carlsson, R.; Eerland, A.; Fijten, R.; Fondberg, R.; Heininga, V.E.; Heunis, S.; Koh, W.Q.; Masselink, M.; et al. Towards Wide-Scale Adoption of Open Science Practices: The Role of Open Science Communities. Sci. Public Policy 2021, 48, 605–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simard, M.-A.; Ghiasi, G.; Mongeon, P.; Larivière, V. National Differences in Dissemination and Use of Open Access Literature. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0272730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pampel, H. Promoting Open Access in Research-Performing Organizations: Spheres of Activity, Challenges, and Future Action Areas. Publications 2023, 11, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van ’t Veer, A. Fostering a National Community-Led Network to Accelerate Open Science Practices: Foster OSC-NL. In ResearchEquals; Liberate Science GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, J.Y.; Wieland, L.S.; Lee, M.S.; Liu, J.; Witt, C.M.; Moher, D.; Cramer, H. Open Science Practices in Traditional, Complementary, and Integrative Medicine Research: A Path to Enhanced Transparency and Collaboration. Integr. Med. Res. 2024, 13, 101047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, E.A. Linking Policy and Practice in Monitoring Socially Responsible Research and Innovation (RRI): A Conceptual Framework to Evaluate Progress through the UNESCO-Led Recommendation on Science and Scientific Researchers. Open Res. Eur. 2023, 2, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farrugia, D.M.; Vilches, S.L.; Gerber, A. Effective Inter-Organisational Networks for Responsible Research and Innovation and Global Sustainability: A Scoping Review. Open Res. Eur. 2022, 1, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lola, M.S.; Ramlee, M.N.A.; Isa, H.; Abdullah, M.I.; Hussin, M.F.; Zainuddin, N.H.; Rahman, M.N. Forecasting towards Planning and Sustainable Development Based on a System Dynamic Approach: A Case Study of the Setiu District, State of Terengganu, Malaysia. Open J. Stat. 2016, 6, 931–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddi, A.; Lardreau, E.; Sapinho, D. Open Access in Europe: A National and Regional Comparison. Scientometrics 2021, 126, 3131–3152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalheiro, E.A.; Oliveira, I.R.; Leandro, D.; Kontz, L.B. Governance, Development, and Environment: Pathways to a Sustainable Future. Sustain. Futures 2025, 100813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, B.; Mackay, M.; Novaglio, C.; Fullbrook, L.; Murunga, M.; Sbrocchi, C.; McDonald, J.; McCormack, P.C.; Alexander, K.; Fudge, M.; et al. The Future of Ocean Governance. Rev. Fish Biol. Fish. 2022, 32, 253–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, O.R.; Osherenko, G.; Ekstrom, J.; Crowder, L.B.; Ogden, J.; Wilson, J.A.; Day, J.C.; Douvere, F.; Ehler, C.N.; McLeod, K.L.; et al. Solving the Crisis in Ocean Governance: Place-Based Management of Marine Ecosystems. Environ. Sci. Policy Sustain. Dev. 2007, 49, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMento, J.F.; Hickman, A.J. Environmental Governance of the Great Seas: Law and Effect; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Torfing, J.; Sørensen, E. The European Debate on Governance Networks: Towards a New and Viable Paradigm? Policy Soc. 2014, 33, 329–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, R.; Evans, K.; Alexander, K.; Bettiol, S.; Corney, S.; Cullen-Knox, C.; Cvitanovic, C.; de Salas, K.; Emad, G.R.; Fullbrook, L.; et al. Connecting to the Oceans: Supporting Ocean Literacy and Public Engagement. Rev. Fish Biol. Fish. 2022, 32, 123–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skarlatidou, A.; Haklay, M. Citizen Science Impact Pathways for a Positive Contribution to Public Participation in Science. J. Sci. Commun. 2021, 20, A02. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidstrup, M.V.; Gabova, S.; Kilintzis, P.; Samara, E.; Kouskoura, A.; Bakouros, Y.; Roth, F. The RRI Citizen Review Panel: A Public Engagement Method for Supporting Responsible Territorial Policymaking. J. Innov. Entrep. 2024, 13, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schimmelfennig, F.; Leuffen, D.; De Vries, C.E. Differentiated Integration in the European Union: Institutional Effects, Public Opinion, and Alternative Flexibility Arrangements. Eur. Union Politics 2023, 24, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galiè, A.; McLeod, A.; Campbell, Z.A.; Ngwili, N.; Terfa, Z.G.; Thomas, L.F. Gender Considerations in One Health: A Framework for Researchers. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1345273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.R. Ethics in Social Science Research: Challenges and Future Directions. In Ethics in Social Science Research; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2024; pp. 243–263. [Google Scholar]

- Correia, M.I.T.D. Ethics in Research. Clin. Nutr. Open Sci. 2023, 47, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappelletto, M.; Giuffredi, R.; Kastanidi, E.; Vassilopoulou, V.; L’Astorina, A. Grounding Ocean Ethics While Sharing Knowledge and Promoting Environmental Responsibility: Empowering Young Ambassadors as Agents of Change. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 717789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hügel, S.; Davies, A.R. Public Participation, Engagement, and Climate Change Adaptation: A Review of the Research Literature. WIREs Clim. Change 2020, 11, e645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cederroth, C.R.; Earp, B.D.; Gómez Prada, H.C.; Jarach, C.M.; Lir, S.A.; Norris, C.M.; Pilote, L.; Raparelli, V.; Rochon, P.; Sahraoui, N.; et al. Integrating Gender Analysis into Research: Reflections from the Gender-Net Plus Workshop. EClinicalMedicine 2024, 74, 102728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmén, R.; Arroyo, L.; Müller, J.; Reidl, S.; Caprile, M.; Unger, M. Integrating the Gender Dimension in Teaching, Research Content & Knowledge and Technology Transfer: Validating the EFFORTI Evaluation Framework Through Three Case Studies in Europe. Eval. Program Plan. 2020, 79, 101751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Project | Key ORRI Principles Addressed | Notable Practices/Outputs |

|---|---|---|

| DOORS [39] | Open Access, Governance, Science Education, Public Engagement, Ethics | System of Systems for data sharing; Knowledge Transfer & Training (KTT) framework; Blue Growth Accelerator (BGA); inclusive decision-making tools. |

| Black Sea CONNECT [40] | Governance, Public Engagement, Open Science, Ethics | Strategic Research and Innovation Agenda (SRIA); Black Sea Young Ambassadors promoting ORRI values across the region. |

| BRIDGE-BS [41] | Ethics, Open Access, Public Engagement, Science Education, Governance | Open-access models; participatory governance; D7.1 (Accelerator Platform Guidelines); D9.1 (Good Practices for Training); co-creation; informal education. |

| LitOUTer [42] | Public Engagement, Science Education, Open Access, Responsiveness | Marine litter modelling; stakeholder involvement; decision-support tools; transboundary collaboration. |

| MARLITER [43] | Open Access, Science Education, Ethics, Gender Equality | Web-based monitoring tool; youth training programs, Guidebook on Marine Litter Reduction with circular economy and ethics components. |

| ANEMONE [44] | Public Engagement, Science Education | Citizen science activities (D4.1–D4.3); cetacean monitoring; community participation in marine data collection and education. |

| MARINA [45] | Public Engagement, Science Education, Governance | 45 Multi-Stakeholder Mobilization & Mutual Learning (MML) workshops; dialogue across sectors; use of citizen science for awareness and knowledge co-production. |

| ORRI Pillar | Black Sea Region (Scaffolded Adaptation Model) | Northern/Western Europe (Structurally Embedded Model) |

|---|---|---|

| Public Engagement | Project-driven, often externally initiated (EU-funded) | Integrated into national strategies and supported by long-term funding |

| Science Education | Delivered through workshops, summer schools, and project-based outreach | Part of the formal and informal education systems, supports lifelong learning |

| Open Access | Limited institutional policies, low infrastructure support | National mandates and policies ensure open access to research outputs |

| Gender Equality | Largely absent from research design and leadership structures | Mandated and monitored; supported by gender action plans and inclusion policies |

| Ethics | Fragmented or ad hoc, rarely institutionally formalized | Well-developed ethical review systems with institutional and national oversight |

| Governance | Disconnected, low coordination across institutions and borders | Strong governance mechanisms; inclusive, cross-sectoral, and policy-aligned |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bisinicu, E.; Lazar, L.; Candea, M.M.; Serra, E.G. Advancing Marine Sustainability Capacity in the Black Sea—Insights from Open Responsible Research and Innovation (ORRI). Sustainability 2025, 17, 5656. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125656

Bisinicu E, Lazar L, Candea MM, Serra EG. Advancing Marine Sustainability Capacity in the Black Sea—Insights from Open Responsible Research and Innovation (ORRI). Sustainability. 2025; 17(12):5656. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125656

Chicago/Turabian StyleBisinicu, Elena, Luminita Lazar, Mihaela Mirea Candea, and Elena Garcia Serra. 2025. "Advancing Marine Sustainability Capacity in the Black Sea—Insights from Open Responsible Research and Innovation (ORRI)" Sustainability 17, no. 12: 5656. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125656

APA StyleBisinicu, E., Lazar, L., Candea, M. M., & Serra, E. G. (2025). Advancing Marine Sustainability Capacity in the Black Sea—Insights from Open Responsible Research and Innovation (ORRI). Sustainability, 17(12), 5656. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125656