Exploring Sustainable HRM Through the Lens of Employee Wellbeing

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Sustainable HRM

- Socially responsible HRM refers to a socially responsible approach to HRM, which includes corporate social responsibility-related personnel policies.

- Green HRM focuses on environmentally conscious HR strategies, including hiring environmentally conscious staff, providing green training, evaluating performance against the organization’s green standards, and providing a green reward system for achieving green goals.

- Triple-bottom-line HRM seeks to accomplish the environmental, social, and economic goals simultaneously to attain sustainability by minimizing the adverse environmental effects caused by an organization’s operations.

- Common good HRM intends to use HRM policies and practices to help all employees. Such policies and practices involve the participation of employees in decision making, proper grievance handling, job security, and providing help to employees in cases of need.

2.2. Employee Wellbeing

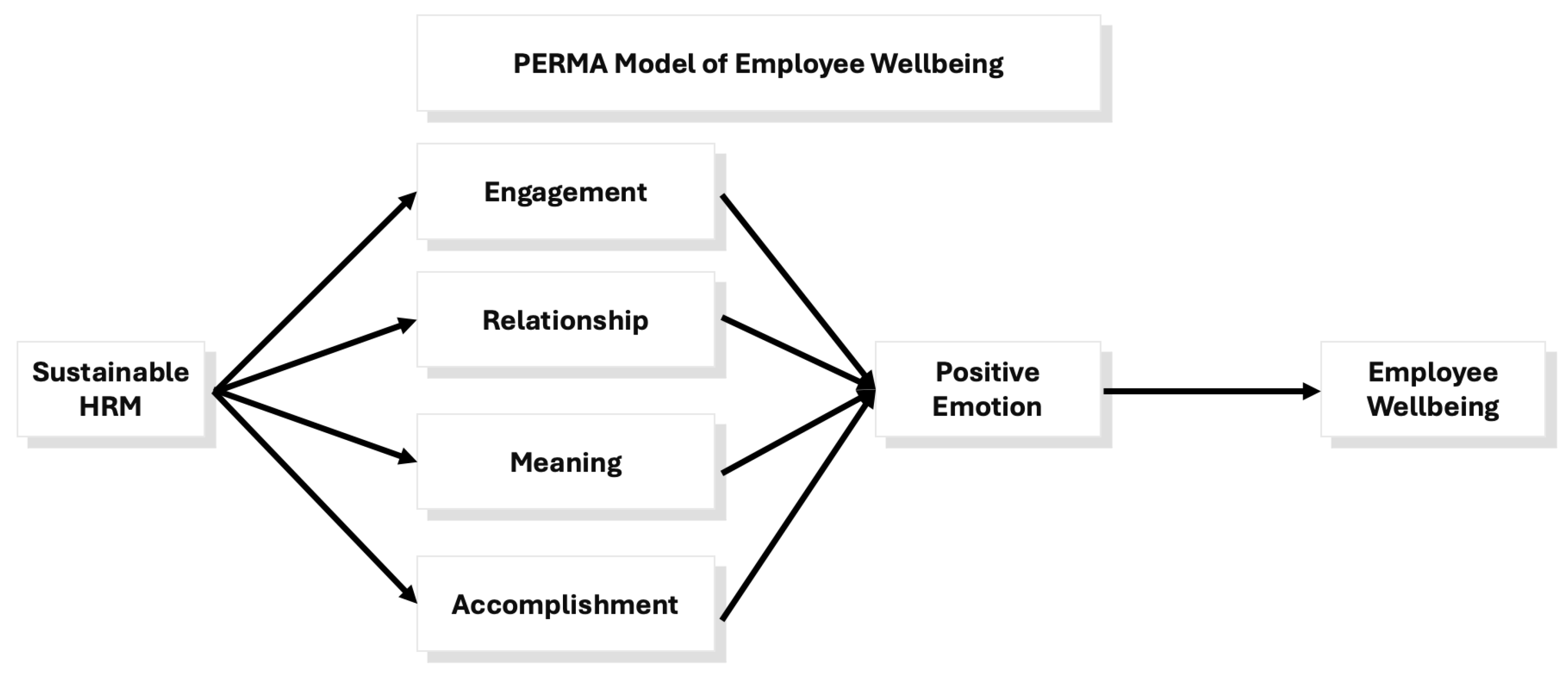

2.3. PERMA Model of Wellbeing

3. Theoretical Framework

- Investing in employees

- Recruitment and selection

- Training and development

- Mentoring and career support

- Providing engaging work

- Jobs designed to provide autonomy and challenge

- Information provision and feedback

- Skill utilization

- Positive social and physical environment

- Health and safety a priority

- Equal opportunities/diversity management

- Zero tolerance for bullying and harassment

- Required and optional social interaction

- Fair collective rewards/high basic pay

- Employment security/employability

- Voice

- Extensive two-way communication

- Employee surveys

- Collective representation

- Organizational support

- Participative/supportive management

- Involvement in climate and practices

- Flexible and family-friendly work arrangements

- Developmental performance management

3.1. Engagement

- Engaging work and task identity with job resources;

- Jobs designed to provide autonomy and challenge;

- Information provision and feedback;

- Flexible work schedule, family-friendly work arrangements;

- Work–life balance, managing work–family conflict, life and family support;

- Healthy and safe working conditions, mental health support;

- Job security.

3.2. Relationship

- Equal opportunities, diversity management, zero tolerance for bullying/harassment;

- Two-way communication, information sharing and employee surveys/voice;

- Social interaction, involvement, teamwork, partnership, and collective representation;

- Interpersonal relationships and relationship with immediate manager;

- Participative and supportive management and leadership;

- Sufficient supervisor and organizational support.

3.3. Meaning

- Challenging jobs, job quality, enriching and meaningful tasks;

- Strengthening and empowering (autonomy, voice, and feedback);

- Competency and skill variety and utilization;

- Self-motivation and self-efficacy;

- Employees’ role in an organization;

- Involved climate and team-building culture;

- Investment in employees and indirect compensation;

- Attractive career future and organizational support for career-related activities.

3.4. Accomplishment

- Employee learning and development;

- Developmental performance management;

- Mentoring, career support, and organizational support;

- Fair rewards and compensation system;

- Recognition program;

- Tolerance to errors.

4. Discussions

5. Conclusions and Implications

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations. Sustainability. 2025. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/academic-impact/sustainability#:~:text=In%201987%2C%20the%20United%20Nations,to%20meet%20their%20own%20needs (accessed on 4 April 2025).

- United Nations. The 17 Goals. 2025. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 4 April 2025).

- Grawitch, M.J.; Ballard, D.W.; Erb, K.R. To be or not to be (stressed): The critical role of a psychologically healthy workplace in effective stress management. Stress Health 2015, 31, 264–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabriel, K.P.; Aguinis, H. How to prevent and combat employee burnout and create healthier workplaces during crises and beyond. Bus. Horiz. 2022, 65, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinar, A.; Bilodeau, S. Sustainable workplace mental wellbeing for sustainable SMEs: How? Sustainability 2022, 14, 5290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, A.G. The impact of sustainable practices on employee well-being and organizational success. Braz. J. Dev. 2025, 11, e78599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abid, G.; Ahmed, S.; Elahi, N.; Ilyas, S. Antecedents and mechanism of employee well-being for social sustainability: A sequential mediation. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2020, 24, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadick, A.; Kamardeen, I. Enhancing employees’ performance and well-being with nature exposure embedded office workplace design. J. Build. Eng. 2020, 32, 101789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasisi, T.T.; Constanta, E.; Eluwole, K.K. Workplace favoritism and workforce sustainability: An analysis of employees’ well-being. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, D.E. Human resource management and employee well-being: Towards a new analytic framework. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2017, 27, 22–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramar, R. Beyond strategic human resource management: Is sustainable human resource management the next approach? Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2014, 25, 1069–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huselid, M.A. The impact of human resource management practices on turnover, productivity, and corporate financial performance. Acad. Manag. J. 1995, 38, 635–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehnert, I.; Parsa, S.; Roper, I.; Wagner, M.; Muller-Camen, M. Reporting on sustainability and HRM: A comparative study of sustainability reporting practices by the world’s largest companies. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2016, 27, 88–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combs, J.; Liu, Y.; Hall, A.; Ketchen, D. How much do high-performance work practices matter? A meta-analysis of their effects on organizational performance. Pers. Psychol. 2006, 59, 501–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boxall, P.F.; Purcell, J. Strategy and Human Resource Management, 2nd ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lawler, J.J.; Chen, S.J.; Wu, P.C.; Bae, J.; Bai, B. High performance work systems in foreign subsidiaries of American Multinationals: An institutional model. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2011, 42, 202–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godard, J. High performance and the transformation of work? The implications of alternative work practices for the experience and outcomes of work. Ind. Labor Relat. Rev. 2001, 54, 776–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marescaux, E.; De Winne, S.; Forrier, A. Developmental HRM, employee well-being and performance: The moderating role of developing leadership. Eur. Manag. Rev. 2019, 16, 317–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariappanadar, S. Stakeholder harm index: A framework to review work intensification from the critical HRM perspective. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2014, 24, 313–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peccei, R.; van de Voorde, K.; van Veldhoven, M. HRM, well-being and performance: A theoretical and empirical review. In HRM and Performance: Achievements and Challenges; Paauwe, J., Guest, D., Wright, P., Eds.; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2013; pp. 15–45. [Google Scholar]

- Peccei, R.; Van De Voorde, K. Human resource management-well-being-performance research revisited: Past, present, and future. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2019, 29, 539–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauff, S.; Krick, A.; Klebe, L.; Felfe, J. High-performance work practices and employee wellbeing—Does health-oriented leadership make a difference? Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 833028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartram, T.; Cooper, B.; Cooke, F.; Wang, J. Thriving in the face of burnout? The effects of wellbeing-oriented HRM on the relationship between workload, burnout, thriving and performance. Empl. Relat. 2023, 45, 1234–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhoir, M.; Sinha, V. Employee well-being human resource practices: A systematic literature review and directions for future research. Future Bus. J. 2024, 10, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, J. Putting employees at the centre of sustainable HRM: A review, map and research agenda. Empl. Relat. 2022, 44, 533–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, F.L.; Dickmann, M.; Parry, E. Building sustainable societies through human-centred human resource management: Emerging issues and research opportunities. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2022, 33, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herlina, M.G.; Iskandar, K. Integrating sustainable HRM, AI, and employee well-being to enhance engagement in Greater Jakarta: An SDG 3 perspective. In Proceedings of the E3S Web Conference, London, UK, 20–22 August 2025; Volume 601, p. 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manuti, A.; Giancaspro, M.L.; Molino, M.; Ingusci, E.; Russo, V.; Signore, F.; Zito, M.; Cortese, C.G. “Everything will be fine”: A study on the relationship between employees’ perception of sustainable HRM practices and positive organizational behavior during COVID19. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaugg, R.J.; Blum, A.; Thom, N. Sustainability in Human Resource Management: Evaluation Report; IOP-Press: Bern, Switzerland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Thom, N.; Zaugg, R.J. Nachhaltiges und innovatives personal management. In Innovations Management; Nachhaltiges Schwarz, E.J., Ed.; Gabler: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2004; pp. 215–245. [Google Scholar]

- Wikhamn, W. Innovation, sustainable HRM and customer satisfaction. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 76, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl, G.K.; Brewster, C.J.; Collings, D.G.; Hajro, A. Enhancing the role of human resource management in corporate sustainability and social responsibility: A multi-stakeholder, multidimensional approach to HRM. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2020, 30, 100708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aust, I.; Matthews, B.; Muller-Camen, M. Common good HRM: A paradigm shift in sustainable HRM? Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2020, 30, 100705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faisal, S. Twenty-years journey of sustainable human resource management research: A bibliometric analysis. Adm. Sci. 2023, 13, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stadler, R.; Walters, T.; Jepson, A. Sustainable humans: A framework for applying sustainable HRM principles to the events industry. Event Manag. 2022, 26, 1817–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, I.J.; Flint-Taylor, J. Leadership, psychological well-being and organizational outcomes. In The Oxford Handbook on Organisational Well-Being; Cartwright, S., Cooper, C., Eds.; Robertson Cooper: Manchester, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Western, M.; Tomaszewski, W. Subjective wellbeing, objective wellbeing and inequality in Australia. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0163345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Layard, R. Happiness: Lessons from a New Science; Penguin: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E. Subjective well-being: The science of happiness and a proposal for a national index. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundqvist, C. Well-being in competitive sports—The feel-good factor? A review of conceptual considerations of well-being. Psychol. Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. 2001, 4, 109–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 141–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryff, C.D.; Keyes, C.L.M. The structure of psychological well-being revisited. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 69, 719–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterman, A.S. Two conceptions of happiness: Contrasts of personal expressiveness (eudaimonia) and hedonic enjoyment. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1993, 64, 678–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, M.E. Flourish: A Visionary New Understanding of Happiness and Wellbeing; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Promoting Mental Health: Concepts, Emerging Evidence, Practice: Summary Report; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Warr, P. Psychology at Work. Penguin UK: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Peccei, R. Human Resource Management and the Search for the Happy Workplace; Erasmus Research Institute of Management, Rotterdam School of Management, Rotterdam School of Economics: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Tehrani, N.; Humpage, S.; Willmott, B.; Haslam, I. What’s Happening with Well-Being at Work? Change Agenda; Chartered Institute of Personnel Development: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Rothmann, S. From happiness to flourishing at work: A Southern African perspective. In Wellbeing Research in South Africa; Wissing, M., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2013; pp. 123–151. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker, A.B.; Oerlemans, W. Subjective well-being in organizations. In The Oxford Handbook of Positive Organizational Scholarship; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011; Volume 49, pp. 178–189. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E.; Lucas, R.E.; Oishi, S. Subjective well-being: The science of happiness and life satisfaction. In Handbook of Positive Psychology; Snyder, C.R., Lopez, S., Eds.; Oxford University Press: London, UK, 2002; pp. 63–73. [Google Scholar]

- Page, K.M.; Vella-Brodrick, D.A. The ‘what’, ‘why’ and ‘how’ of employee well-being: A new model. Soc. Indic. Res. 2009, 90, 441–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taris, T.W.; Schaufeli, W.B. Individual well-being and performance at work: A conceptual and theoretical overview. In Well-Being and Performance at Work: The Role of Context; van Veldhoven, M., Peccei, R., Eds.; Psychology Press: East Sussex, UK, 2015; pp. 15–34. [Google Scholar]

- Tuzovic, S.; Kabadayi, S. The influence of social distancing on employee wellbeing: A conceptual framework and research agenda. J. Serv. Manag. 2020, 32, 145–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, T.A.; Cropanzano, R.; Bonett, D.G. The moderating role of employee positive well being on the relation between job satisfaction and job performance. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2007, 12, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, M.E. Authentic Happiness: Using The New Positive Psychology to Realize Your Potential for Lasting Fulfillment; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg, A.; Doyle, N. Psychology at work: Improving wellbeing and productivity in the workplace. In Psychology at Work; Warr, P., Ed.; British Psychological Society: London, UK, 2017; pp. 44–62. [Google Scholar]

- Harter, J.K.; Schmidt, F.L.; Keyes, C.L.M. Well-being in the workplace and its relationship to business outcomes. In Flourishing: The Positive Person and the Good Life; Keyes, C.L.M., Haidt, J., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2003; pp. 205–224. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E. Subjective well-being. Psychol. Bull. 1984, 95, 542–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryff, C.D.; Singer, B.H. Know thyself and become what you are: A eudaimonic approach to psychological well-being. J. Happiness Stud. 2008, 9, 13–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beacham, A.; Brainard, A.; Janosy, N.; Reese, J. A brief evidence-based intervention to enhance workplace well-being and flourishing in health care professionals: Feasibility and pilot outcomes. J. Wellness 2020, 2, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavin, S.J.; Schindler, D.; Chibnall, J.T.; Fendell, G.; Shoss, M. PERMA: A model for institutional leadership and culture change. Acad. Med. 2012, 87, 1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kern, M.L.; Waters, L.E.; Adler, A.; White, M.A. Assessing employee wellbeing in schools using a multifaceted approach: Associations with physical health, life satisfaction, and professional thriving. Psychology 2014, 5, 500–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, M.L.; Waters, L.E.; Adler, A.; White, M.A. A multidimensional approach to measuring well-being in students: Application of the PERMA framework. J. Posit. Psychol. 2015, 10, 262–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bynum, J.A. Leadership Styles and the Well-Being of Special Education Teachers. Ph.D. Thesis, Grand Canyon University, Phoenix, AZ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kun, A.; Gadanecz, P. Workplace happiness, well-being and their relationship with psychological capital: A study of Hungarian teachers. Curr. Psychol. 2019, 41, 185–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanmugam, P.; Hidayat, R. Assessing grit and well-being of Malaysian ESL teachers: Application of the PERMA model. Malays. J. Learn. Instr. 2022, 19, 153–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purwaniningtyas, D.A.; Adira, N.; Kusmaryani, R.E.; Nurhayati, S.R. Teacher well-being & engagement: The importance of teachers’ interpersonal relationships quality at school. Psychol. Res. Interv. 2023, 6, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovich, M.; Simpson, V.; Foli, K.; Hass, Z.; Phillips, R. Application of the PERMA model of well-being in undergraduate students. Int. J. Community Well-Being 2023, 6, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donaldson, S.I.; van Zyl, L.E.; Donaldson, S.I. PERMA+4: A framework for work-related wellbeing, performance and positive organizational psychology 2.0. Front. Psychol. 2022, 12, 817244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehnert, I. Sustainable human resource management. In A Conceptual and Exploratory Analysis from a Paradox Perspective; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, E.; Taylor, S.; Muller-Camen, M. HRM’s Role in Corporate Social and Environmental Sustainability; Research Report SHRM Society: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- De Prins, P.; Van Beirendonck, L.; De Vos, A.; Segers, J. Sustainable HRM: Bridging theory and practice through the ‘Respect Openness Continuity (ROC)’-model. Manag. Rev. 2014, 25, 263–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stankeviciute, Z.; Savaneviciene, A. Designing sustainable HRM: The core characteristics of emerging field. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stankeviciute, Z.; Savaneviciene, A. Can sustainable HRM reduce work-related stress, work-family conflict, and burnout? Int. Stud. Manag. Organ. 2019, 49, 79–98. [Google Scholar]

- Abiola, T.; Olorukooba, H.O.; Afolayan, J. Wellbeing elements leading to resilience among undergraduate nursing students. Int. J. Afr. Nurs. Sci. 2017, 7, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaghaghi, F.; Abedian, Z.; Forouhar, M.; Esmaily, H.; Eskandarnia, E. Effect of positive psychology interventions on psychological well-being of midwives: A randomized clinical trial. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2019, 8, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, C.W.; Burke, J.; Muzyk, A. Contributing to a healthier world: Exploring the impact of wellbeing on nursing burnout. J. Happiness Health 2022, 2, 70–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oddiri, U.; Islam, S.; Lu, W. Understanding the impact of Schwartz Rounds on pediatric clinicians’ well-being using the positive emotion, engagement, relationships, meaning, and accomplishment (PERMA) model for flourishing: A qualitative analysis. Cureus 2023, 15, e46324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephan, A.T. Grandparent caregiver wellbeing: A strengths-based approach utilizing the positive emotions, engagement, relationships, meaning, and accomplishment (PERMA) framework. J. Fam. Issues 2023, 44, 1400–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, M.E. Authentic Happiness; Free Press: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson, B.L. Positive emotions and upward spirals in organizations. In Positive Organizational Scholarship; Cameron, K., Dutton, J., Quinn, R., Eds.; Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Inc.: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2003; pp. 163–175. [Google Scholar]

- Hazelton, S. Positive emotions boost employee engagement: Making work fun brings individual and organizational success. Hum. Resour. Manag. Int. Dig. 2014, 22, 34–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouweneel, E.; Le Blanc, P.M.; Schaufeli, W.B. Don’t leave your heart at home: Gain cycles of positive emotions, resources, and engagement at work. Career Dev. Int. 2012, 17, 537–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.S.; Statler, M. Material matters: Increasing emotional engagement in learning. J. Manag. Educ. 2014, 38, 586–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, M.E. PERMA and the building blocks of well-being. J. Posit. Psychol. 2018, 13, 333–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, S.I. Evaluating Employee Positive Functioning and Performance: A Positive Work and Organizations Approach. Ph.D. Thesis, Claremont Graduate University, Claremont, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson, S.I.; Heshmati, S.; Lee, J.Y.; Donaldson, S.I. Examining building blocks of well-being beyond PERMA and self-report bias. J. Posit. Psychol. 2020, 16, 811–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. Finding Flow: The Psychology of Engagement with Everyday Life; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kahn, W.A. Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Acad. Manag. J. 1990, 33, 692–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. Towards a model of work engagement. Career Dev. Int. 2008, 13, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Xanthopoulou, D. Creativity and charisma among female leaders: The role of resources and work engagement. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2013, 24, 2760–2779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. The job demands-resources model: State of the art. J. Manag. Psychol. 2007, 22, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Verbeke, W. Using the job demands-resources model to predict burnout and performance. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2004, 43, 83–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B.; Nachreiner, F.; Schaufeli, W.B. The job demands-resources model of burnout. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.; Bakker, A.; Van Rhenen, W. How changes in job demands and resources predict burnout, work engagement, and sickness absenteeism. J. Organ. Behav. 2009, 30, 893–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Voorde, K.; Veld, M.; van Veldhoven, M. Connecting empowerment-focused HRM and labour productivity to work engagement: The mediating role of job demands and resources. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2016, 26, 192–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutton, J.; Heaphy, E. The power of high-quality connections. In Positive Organizational Scholarship; Cameron, K., Dutton, J., Quinn, R., Eds.; Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Inc.: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2003; pp. 263–278. [Google Scholar]

- Colbert, A.E.; Bono, J.E.; Purvanova, R.K. Flourishing via workplace relationships: Moving beyond instrumental support. Acad. Manag. J. 2016, 59, 1199–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P.M. Exchange and Power in Social Life: New Introduction by the Author; Transaction Publisher: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Blau, P.M. Justice in social exchange. Sociol. Inq. 1964, 34, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouldner, A.W. The norm of reciprocity: A preliminary statement. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1960, 25, 161–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, R.; Fasolo, P.; Davis-Lamastro, V. Perceived organisational support and employee diligence, commitment and innovation. J. Appl. Psychol. 1990, 75, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryee, S.; Budhwar, P.S.; Chen, Z.X. Trust as a mediator of the relationship between organizational justice and work outcomes: Test of a social exchange model. J. Organ. Behav. 2002, 23, 267–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlwood, A. The employee experience of high involvement management in Britain. In Unequal Britain at Work; Felstead, A., Gallie, D., Green, F., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015; pp. 167–190. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R.; Deci, E. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, T. Positive organizational behavior: An idea whose time has truly come. J. Organ. Behav. 2003, 24, 437–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B.; Branigan, C. Positive emotions broaden the scope of attention and thought-action repertoires. Cogn. Emot. 2003, 19, 313–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steger, M.F. Meaning and well-being. In Handbook of Well-Being; Diener, E., Oishi, S., Tay, L., Eds.; DEF Publishers: Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 2018; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, B.; Dekas, K.; Wrzesniewski, A. On the meaning of work: A theoretical integration and review. Res. Organ. Behav. 2010, 30, 91–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, M.; Ashforth, B. Fostering meaningfulness in working and at work. In Positive Organizational Scholarship; Cameron, K., Dutton, J., Quinn, R., Eds.; Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Inc.: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2003; pp. 309–327. [Google Scholar]

- Appelbaum, E.; Batt, R. The New American Workplace; ILR Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Appelbaum, E.; Bailey, R.; Berg, P.; Kalleberg, A. A Manufacturing Competitive Advantage: The Effects of High Performance Work Systems on Plant Performance and Company Outcomes; Cornell University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Duckworth, A. Grit: The Power of Passion and Perseverance; Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Baranik, L.E.; Lau, A.R.; Stanley, L.J.; Barron, K.E.; Lance, C.E. Achievement goals in organizations: Is there support for mastery-avoidance? J. Manag. Issues 2013, 25, 46–61. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, J.; Kern, M.L. The PERMA-Profiler: A brief multidimensional measure of flourishing. Int. J. Wellbeing 2016, 6, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J.; Wright, P. On becoming a strategic partner: Examining the role of human resources in gaining competitive advantage. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 1998, 37, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arulrajah, A.A.; Opatha, H.H.D.N.P. Analytical and theoretical perspectives on green human resource management: A simplified underpinning. Int. Bus. Res. 2016, 9, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madero-Gomez, S.M.; Rubio Leal, Y.L.; Olivas-Lujan, M.; Yusliza, M.Y. Companies could benefit when they focus on employee wellbeing and the environment: A systematic review of sustainable human resource management. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sustainable HRM | PERMA Model |

|---|---|

| Engagement |

| Relationship |

| Meaning |

| Accomplishment |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bai, B. Exploring Sustainable HRM Through the Lens of Employee Wellbeing. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5646. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125646

Bai B. Exploring Sustainable HRM Through the Lens of Employee Wellbeing. Sustainability. 2025; 17(12):5646. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125646

Chicago/Turabian StyleBai, Bing. 2025. "Exploring Sustainable HRM Through the Lens of Employee Wellbeing" Sustainability 17, no. 12: 5646. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125646

APA StyleBai, B. (2025). Exploring Sustainable HRM Through the Lens of Employee Wellbeing. Sustainability, 17(12), 5646. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125646