Talent Development in Science and Technology Parks (STPs) Within the Context of Sustainable Education Systems: Experiential Learning and Mentorship Practices in a Phenomenological Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. STPs and Sustainable Talent Development in Higher Education: A Conceptual Framework

1.1.1. The Role of STPs in Sustainable Education Systems

1.1.2. Talent Development Through Experiential Learning

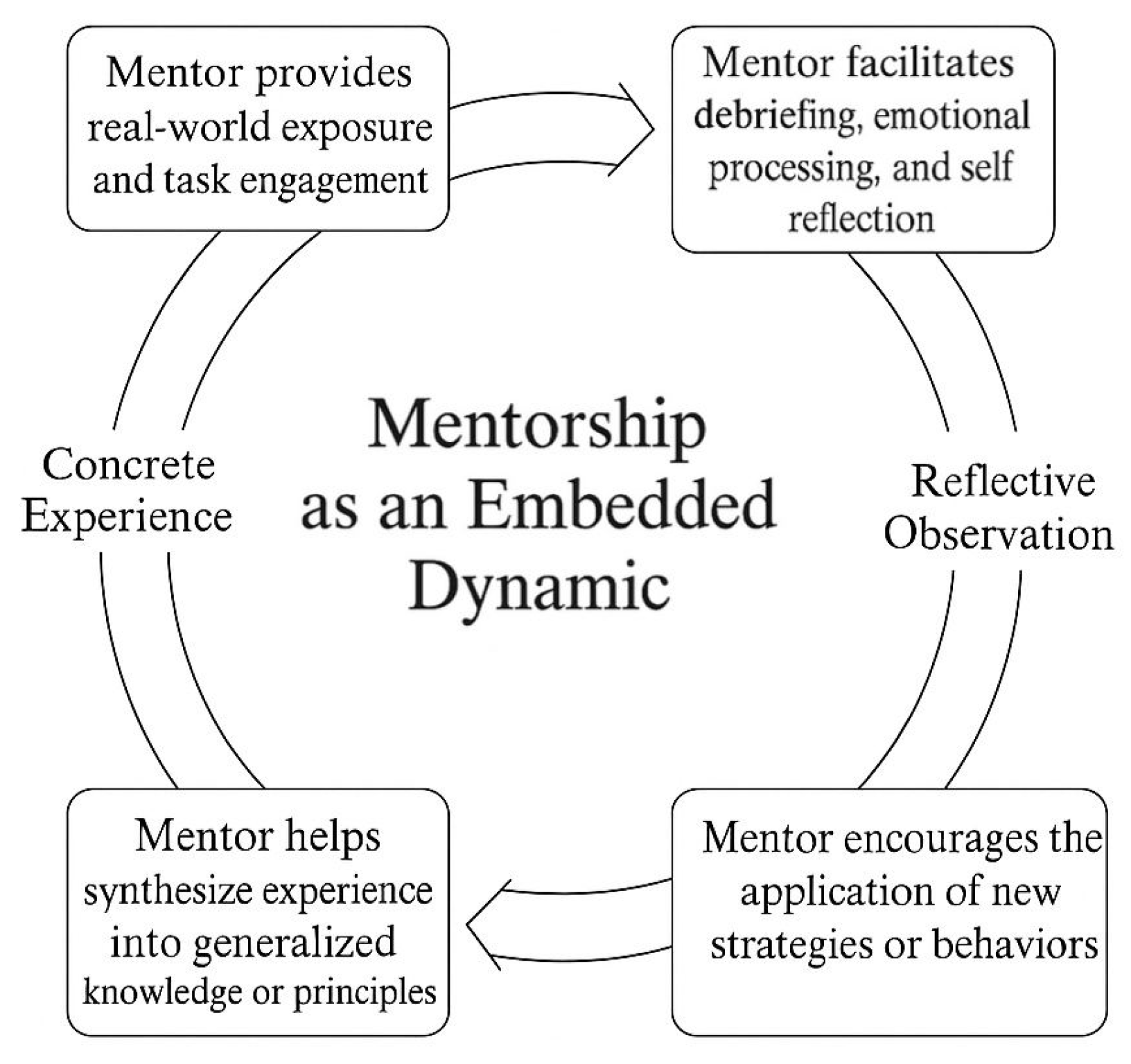

1.1.3. Talent Development Through Mentorship

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Data Collection Strategy

2.4. Data Analysis and Thematic Categorization

3. Findings

3.1. Main Theme 1: Talent Development Through Experiential Learning

3.1.1. Transfer of Theoretical Knowledge into Practice

- Learning through Real Tasks

- Testing Knowledge in the Field

- Comprehension through Application

3.1.2. Deepening of Learning Through Experience

- Development of Flexible Thinking

- Awareness of Knowledge

- New Learning Strategies

3.1.3. Concretization and Retention of Learning

- Internalization of Knowledge

- Emotional Engagement through Application

- Memorability

3.1.4. Professional Identity and Role Awareness

- Feeling Like an Employee

- Taking Responsibility

- Role Integration within the Team

3.1.5. Career Orientation and Transformative Awareness

- Discovery of Vocational Interest/Disinterest

- Clarification of Future Plans

- Development of Self-Awareness

3.2. Main Theme 2: Talent Development Through Mentorship

3.2.1. Technical and Psychosocial Guidance from the Mentor

- Task-Oriented Guidance

- Encouragement to Ask Questions

- Support for Self-Confidence

3.2.2. The Mentor as a Role Model

- Observation of Professional Behavior

- Behavioral Modeling

- Aspiration to Assume Similar Roles

3.2.3. Trust and Openness in the Mentorship

- Open Communication

- Emotional Safety

- Learning without Judgment

3.2.4. Connection Between Mentorship and Career Orientation

- Career Guidance

- Raising Awareness

- Offering Alternative Pathways

4. Discussion

4.1. Experiential Learning as a Driver of Transformative Talent Development

4.2. Strategic Mentorship as a Catalyst for Professional Identity and Career Navigation

5. Conclusions

5.1. Limitations of This Study

5.2. Directions for Future Studies

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| R&D | Research and Development |

| STPs | Science and Technology Park(s) |

Appendix A. Semi-Structured Interview Guide

- What types of experiential learning activities did you participate in during your time at the STP?

- In what ways do you think these experiences contributed to your learning?

- Did you have the opportunity to work one-on-one with a mentor?

- If so, what were the contributions of the mentorship relationship to your development?

- How would you describe the nature of your communication with your mentor?

- How frequently and in what ways did you interact with professionals at the STP?

- Were you able to observe the workplace culture? What kind of impression did it leave on you?

- Do you believe you experienced any development in your professional competencies during this process?

- How would you describe your professional self—has this changed before and after the experience?

- What was the most significant challenge you encountered?

- In your opinion, how can such experiences be made more effective?

- Was there any aspect you felt was lacking during this process?

References

- Benneworth, P.; Hospers, G.J. Urban competitiveness in the knowledge economy: Universities as new planning animateurs. Prog. Plann. 2007, 67, 105–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, M.; Urbano, D.; Fayolle, A. Entrepreneurial activity and regional competitiveness: Evidence from European entrepreneurial universities. J. Technol. Transf. 2016, 41, 105–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etzkowitz, H.; Zhou, C. The Triple Helix: University–Industry–Government Innovation and Entrepreneurship; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collings, D.G.; Mellahi, K. Strategic talent management: A review and research agenda. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2009, 19, 304–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallardo-Gallardo, E.; Dries, N.; González-Cruz, T.F. What is the meaning of ‘talent’ in the world of work? Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2013, 23, 290–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savickas, M.L. The theory and practice of career construction. In Career Development and Counseling: Putting Theory and Research to Work; Brown, S.D., Lent, R.W., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005; pp. 42–70. [Google Scholar]

- Albahari, A.; Pérez-Canto, S.; Barge-Gil, A.; Modrego, A. Technology parks versus science parks: Does the university make the difference? Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2018, 128, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Supporting Entrepreneurship and Innovation in Higher Education in Turkey; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2019; Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/supporting-entrepreneurship-and-innovation-in-higher-education-in-the-netherlands_9789264292048-en.html (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Link, A.N.; Scott, J.T.U.S. science parks: The diffusion of an innovation and its effects on the academic missions of universities. Int. J. Ind. Organ. 2003, 21, 1323–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germain, E.; Klofsten, M.; Löfsten, H.; Mian, S. Science parks as key players in entrepreneurial ecosystems. R&D Manag. 2023, 53, 603–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yüksel, M.; Yıldız, A. Türkiye’de teknoparkların öğrenci gelişimine katkısı: Uygulamalı öğrenme ve istihdam etkileşimi üzerine bir inceleme. Yükseköğr. Bilim Derg. 2020, 10, 45–58. [Google Scholar]

- UNIDO. A New Generation of Science and Technology Parks: Promoting Sustainable Development in the Innovation Economy; United Nations Industrial Development Organization: Vienna, Austria, 2021; Available online: https://hub.unido.org/sites/default/files/publications/Publication_%20New%20Generation%20of%20STI%20parks_2021.pdf (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Cai, Y.; Etzkowitz, H. Theorizing the Triple Helix model: Past, present, and future. Triple Helix 2020, 7, 189–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control; Freeman: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Kolb, D.A. Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Kram, K.E. Mentoring at Work: Developmental Relationships in Organizational Life; Scott Foresman: Glenview, IL, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Glittová, K.; Šipikal, M. University science parks as an innovative tool for university–business cooperation. In Proceedings of the 17th European Conference on Innovation and Entrepreneurship; Academic Conferences International: Reading, UK, 2022; pp. 648–655. Available online: https://papers.academic-conferences.org/index.php/ecie/article/view/399 (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Melo, G.; Sanhueza, D.; Morales, S.; Peña-Lévano, L. What does the pandemic mean for experiential learning? Lessons from Latin America. Appl. Econ. Teach. Resour. 2021, 3, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Ćudić, B.; Alešnik, P.; Hazemali, D. Factors impacting university–industry collaboration in European countries. J. Innov. Entrep. 2022, 11, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rui, C.; Lokshin, B.; Mohnen, P. Knowledge spillovers and science parks: Evidence from China. Ann. Econ. Stat. 2024, 153, 173–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, P.H.; Siegel, D.S.; Wright, M. Science parks and incubators: Observations, synthesis and future research. J. Bus. Ventur. 2005, 20, 165–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, D.S.; Westhead, P.; Wright, M. Science parks and the performance of new technology-based firms: A review of recent UK evidence and an agenda for future research. Small Bus. Econ. 2003, 20, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecluyse, L.; Knockaert, M.; Spithoven, A. The contribution of science parks: A literature review and future research agenda. J. Technol. Transf. 2019, 44, 559–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aranguren, M.J.; Navarro, M.; Wilson, J.R. Strengthening the university’s third mission through building regional innovation ecosystems. Sci. Public Policy 2022, 49, 890–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. The Future of Education and Skills: Education 2030; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2018; Available online: https://www.oecd.org/education/2030-project/ (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- UNESCO. Education for Sustainable Development Goals: Learning Objectives; UNESCO Publishing: Paris, France, 2017; Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000247444 (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- UNESCO. Reimagining Our Futures Together: A New Social Contract for Education; UNESCO Publishing: Paris, France, 2021; Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000379707 (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- OECD. Education Policy Outlook 2021: Shaping Responsive and Resilient Education in a Changing World; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boud, D.; Solomon, N. Work-based learning, graduate attributes and lifelong learning. In Graduate Attributes, Learning and Employability; Hager, P., Holland, S., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2006; pp. 207–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yorke, M. Employability in Higher Education: What It Is–What It Is Not; Learning & Employability Series 1; The Higher Education Academy: York, UK, 2006; Available online: http://www.heacademy.ac.uk/assets/documents/tla/employability/id116_employability_in_higher_education_336.pdf (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Autio, E.; Kenney, M.; Mustar, P.; Siegel, D.; Wright, M. Entrepreneurial innovation: The importance of context. Res. Policy 2014, 43, 1097–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarysse, B.; Wright, M.; Bruneel, J.; Mahajan, A. Creating value in ecosystems: Crossing the chasm between knowledge and business ecosystems. Res. Policy 2014, 43, 1164–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith-Ruig, T. Exploring the links between mentoring and work-integrated learning. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2013, 33, 769–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Competitive Regional Clusters: National Policy Approaches; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şengür, M.; Bayzin, S. Üniversite–sanayi işbirliğinde teknoparkların rolü. Ekon. Sos. Araşt. Derg. 2019, 15, 299–313. [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler, A.; Debatin, T.; Stoeger, H. Learning resources and talent development from a systemic point of view. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2019, 1445, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garg, A. Online education: A learner’s perspective during COVID-19. Asia-Pac. J. Manag. Res. Innov. 2021, 16, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Yu, Z. A meta-analysis and systematic review of the effect of chatbot technology use in sustainable education. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eraut, M. Informal learning in the workplace. Stud. Contin. Educ. 2004, 26, 247–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raelin, J.A. Work-Based Learning: Bridging Knowledge and Action in the Workplace; John Wiley & Sons: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Cadorin, E.; Klofsten, M.; Albahari, A.; Etzkowitz, H. Science parks and the attraction of talents: Activities and challenges. Triple Helix 2019, 6, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, T.D.; Eby, L.T.; Poteet, M.L.; Lentz, E.; Lima, L. Career benefits associated with mentoring for proteges: A meta-analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2004, 89, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crisp, G.; Cruz, I. Mentoring college students: A critical review of the literature between 1990 and 2007. Res. High. Educ. 2009, 50, 525–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivey, G.W.; Dupré, K.E. Workplace mentorship: A critical review. J. Career Dev. 2020, 49, 714–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, H.-G.; Sok, S.; Heng, K. The benefits of peer mentoring in higher education: Findings from a systematic review. J. Learn. Dev. High. Educ. 2024, 31, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, T.D.; Eby, L.T. (Eds.) Definition and evolution of mentoring. In The Blackwell Handbook of Mentoring: A Multiple Perspectives Approach; John Wiley & Sons: Oxford, UK, 2007; pp. 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandler, D.E.; Kram, K.E.; Yip, J. An ecological systems perspective on mentoring at work: A review and future prospects. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2011, 5, 519–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eby, L.T.; Allen, T.D.; Hoffman, B.J.; Baranik, L.E.; Sauer, J.B.; Baldwin, S.; Morrison, M.A.; Kinkade, K.M.; Maher, C.P.; Curtis, S.; et al. An interdisciplinary meta-analysis of the potential antecedents, correlates, and consequences of protégé perceptions of mentoring. Psychol. Bull. 2013, 139, 441–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussey, L.; Campbell-Meier, J. Are you mentoring or coaching? Definitions matter. J. Librariansh. Inf. Sci. 2020, 53, 510–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavanaugh, K.; Cline, D.; Belfer, B.; Chang, S.; Thoman, E.; Pickard, T.; Holladay, C.L. The positive impact of mentoring on burnout: Organizational research and best practices. J. Interprof. Educ. Pract. 2022, 28, 100521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang-Saad, A.Y.; Morton, C.S.; Libarkin, J.C. Entrepreneurship assessment in higher education: A research review for engineering education researchers. J. Eng. Educ. 2018, 107, 263–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holcomb, D. The impact of COVID-19 on formal mentorship: A qualitative study of social work faculty. Adv. Soc. Work 2024, 24, 675–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambunjak, D.; Straus, S.E.; Marusic, A. A systematic review of qualitative research on the meaning and characteristics of mentoring in academic medicine. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2010, 25, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Yang, G.; Yan, C.; Li, J.; Zhang, J. Predictive effect of resilience on self-efficacy during the COVID-19 pandemic: The moderating role of creativity. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 1066759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eby, L.T.; Allen, T.D.; Evans, S.C.; Ng, T.; Dubois, D. Does mentoring matter? A multidisciplinary meta-analysis comparing mentored and non-mentored individuals. J. Vocat. Behav. 2008, 72, 254–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Poth, C.N. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches, 4th ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Van Manen, M. Researching Lived Experience: Human Science for an Action Sensitive Pedagogy; SUNY Press: Albany, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Moustakas, C. Phenomenological Research Methods; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J.A.; Flowers, P.; Larkin, M. Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis: Theory, Method and Research; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Marsick, V.J.; Watkins, K. Informal and incidental learning. New Dir. Adult Contin. Educ. 2001, 89, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Guest, G.; Bunce, A.; Johnson, L. How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods 2006, 18, 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lincoln, Y.S.; Guba, E.G. Naturalistic Inquiry; Sage Publications: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Yıldırım, A.; Şimşek, H. Sosyal Bilimlerde Nitel Araştırma Yöntemleri, 8th ed.; Seçkin Yayıncılık: Ankara, Türkiye, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kallio, H.; Pietilä, A.M.; Johnson, M.; Kangasniemi, M. Systematic methodological review: Developing a framework for a qualitative semi-structured interview guide. J. Adv. Nurs. 2016, 72, 2954–2965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaismoradi, M.; Jones, J.; Turunen, H.; Snelgrove, S. Theme development in qualitative content analysis and thematic analysis. J. Nurs. Educ. Pract. 2016, 6, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, T.H. Experiential learning–A systematic review and revision of Kolb’s model. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2020, 28, 1064–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezirow, J. Transformative Dimensions of Adult Learning; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Mahapoonyanont, N. Reflecting on experiential learning: Insights from higher education students. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Education and Social Science (ICESS-2024), Songkhla, Thailand, 6 August 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Stirling, A.; Kerr, G.; Banwell, J.; MacPherson, E.; Heron, A. A Practical Guide for Work-Integrated Learning; Higher Education Quality Council of Ontario: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2020; Available online: https://heqco.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/HEQCO_WIL_Guide_ENG_ACC.pdf (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Ashforth, B.E.; Mael, F. Social identity theory and the organization. Acad. Manage. Rev. 1989, 14, 20–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregg, M.F.; Magilvy, J.K. Professional identity of Japanese nurses: Bonding into nursing. Nurs. Health Sci. 2001, 3, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Super, D.E. A life-span, life-space approach to career development. In Career Choice and Development, 2nd ed.; Brown, D., Brooks, L., Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1990; pp. 197–261. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, D.T. Careers In and Out of Organisations; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, C. Freedom to Learn; Charles E. Merrill: Columbus, OH, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, T.D.; Eby, L.T. Relationship effectiveness for mentors: Factors associated with learning and quality. J. Manag. 2003, 29, 469–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragins, B.R.; Kram, K.E. (Eds.) The roots and meaning of mentoring. In The Handbook of Mentoring at Work: Theory, Research, and Practice; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2007; pp. 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Nabi, G.; Walmsley, A.; Mir, M.; Osman, S. The impact of mentoring in higher education on student career development: A systematic review and research agenda. Stud. High. Educ. 2024, 50, 739–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracy, S.J. Qualitative quality: Eight “big-tent” criteria for excellent qualitative research. Qual. Inq. 2010, 16, 837–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Code | Gender | Department | Academic Year | Type of Experience | Role in the STPs | Duration (Months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K1 | Female | Industrial Engineering | 4 | Entrepreneurship Project | Co-founder (Business Development) | 6 |

| K2 | Male | Business Administration | 3 | Internship + Mentorship | HR Intern and Mentorship Mentee | 4 |

| K3 | Female | Electrical and Electronics Engineering | 4 | R&D Project Assistantship | Project Assistant | 5 |

| K4 | Male | Computer Engineering | 3 | Start-up Technical Team | Software Development Support Staff | 8 |

| K5 | Female | Molecular Biology | 2 | Laboratory Observation Internship | Molecular Analysis Observer | 3 |

| K6 | Male | International Trade | 4 | Mentorship + Project Planning | Marketing Strategy Support Personnel | 6 |

| K7 | Female | Mechatronics Engineering | 3 | Robotics Applied R&D | Mechanical Prototyping Technician | 7 |

| K8 | Male | Electrical and Electronics Engineering | 2 | Summer Internship | Hardware Assembly Intern | 2 |

| K9 | Female | Psychology | 4 | Mentorship Program | Co-mentor Facilitator | 5 |

| K10 | Male | Political Science | 3 | Field Research + Analysis | Field Researcher | 4 |

| K11 | Female | Software Engineering | 2 | Incubation Center Participation | Software Support Specialist at Incubation Startup | 6 |

| K12 | Male | Business Administration | 4 | Project-Based Consultancy | Business Model Development Officer | 5 |

| K13 | Female | Chemical Engineering | 3 | Mentorship + Laboratory Practice | Chemical Process Observation Assistant | 4 |

| K14 | Male | Economics | 4 | Data Science Project | Data Analytics Assistant | 6 |

| K15 | Female | Civil Engineering | 3 | Start-up Project | Field Simulation Support Technician | 5 |

| Main Themes | Sub-Themes | Codes |

|---|---|---|

| Main Theme 1: Talent Development through Experiential Learning | 1.1. Transfer of Theoretical Knowledge into Practice | (i) Learning through real tasks |

| (ii) Testing knowledge in the field | ||

| (iii) Comprehension through application | ||

| 1.2. Deepening of Learning through Experience | (i) Development of flexible thinking | |

| (ii) Awareness of knowledge | ||

| (iii) New learning strategies | ||

| 1.3. Concretization and Retention of Learning | (i) Internalization of knowledge | |

| (ii) Emotional engagement through application | ||

| (iii) Memorability | ||

| 1.4. Professional Identity and Role Awareness | (i) Feeling like an employee | |

| (ii) Taking responsibility | ||

| (iii) Role integration within the team | ||

| 1.5. Career Orientation and Transformative Awareness | (i) Discovery of vocational interest/disinterest | |

| (ii) Clarification of future plans | ||

| (iii) Development of self-awareness | ||

| Main Theme 2: Talent Development through Mentorship | 2.1. Technical and Psychosocial Guidance from the Mentor | (i) Task-oriented guidance |

| (ii) Encouragement to ask questions | ||

| (iii) Support for self-confidence | ||

| 2.2. The Mentor as a Role Model | (i) Observation of professional behavior | |

| (ii) Behavioral modeling | ||

| (iii) Aspiration to assume similar roles | ||

| 2.3. Trust and Openness in the Mentorship | (i) Open communication | |

| (ii) Emotional safety | ||

| (iii) Learning without judgment | ||

| 2.4. The Relationship between Mentorship and Career Orientation | (i) Career guidance | |

| (ii) Raising awareness | ||

| (iii) Offering alternative pathways |

| Sub-Themes | Codes | Representative Quotes | Frequency (n = 15) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1.1. Transfer of Theoretical Knowledge into Practice | (i) Learning through Real Tasks | P3: “Setting up the circuit wasn’t just an experiment—it affected a part of the final product. That made me much more careful. You learn differently with that kind of responsibility.” P6: “Preparing a sample budget at a desk is one thing, but creating a real cost sheet is something else entirely. Knowing it would be presented made it so exciting for me. I tried really hard not to make mistakes—and that’s when I truly learned.” | 10/15 |

| (ii) Testing Knowledge in the Field | P5: “In the university lab, everything was sterile and orderly. But where we worked here, materials were limited. Still, adapting a method even with limited resources was really exciting—it was a first for me.” P12: “In class, we always had assumptions like ‘the customer will behave like this’ or ‘the market works like that.’ But there was no such clarity in the real data. I had to try many different things just to figure out what to do.” | 8/15 | |

| (iii) Comprehension through Application | P4: “It wasn’t just about writing the code. First, I had to plan it, then test it. In our classes, we learned each of these steps as separate topics each week, but here they were all integrated.” P11: “I knew the code structure, but I learned when, where, and how to use it in the field. The code I wrote didn’t work in one of the modules, and it took me two days to figure out why—but I’ll never forget it again.” | 9/15 | |

| 1.2. Deepening of Learning through Experience | (i) Development of Flexible Thinking | P6: “The budget allocated for the project was insufficient. We quickly had to develop another formula. At first, I panicked, but then I witnessed how our team came together to find a solution and implemented it. It was a completely different experience—a hard lesson that plans can change at any moment.” P10: “When the dataset was updated, I had to delete half of the report. I was frustrated at first, but then I restructured it using different sources. That’s when I realized you have to adapt quickly—giving up wasn’t an option.” | 9/15 |

| (ii) Awareness of Knowledge | P3: “I knew the formulas, but when I was assembling the circuit, some values didn’t match the theory. It made me rethink everything. You need to make adjustments based on the real situation.” P5: “I had memorized some analysis methods, but here I couldn’t decide when to use which one. I had to go back and really learn to understand them.” | 7/15 | |

| (iii) New Learning Strategies | P5: “There was someone working next to me who constantly explained how he thought. Honestly, that was a big advantage for me. By observing and listening to him, I changed my own methods. I even take notes differently now.” P8: “I realized that memorizing everything from start to finish, like I’ve done throughout my education, doesn’t work. When there’s an error in the code, you have to carefully read the specific documentation and look at examples others have created.” | 8/15 | |

| 1.3. Concretization and Retention of Learning | (i) Internalization of Knowledge | P1: “Once I became responsible for the work, I realized I started to think about what I had learned actually meant.” P3: “The formula was no longer just a formula. Once I used it, I could see what it was really for. That’s why it becomes impossible to forget.” | 10/15 |

| (ii) Emotional Engagement through Application | P2: “When I was giving my presentation and my supervisor made eye contact with me and actually listened to what I was saying, I felt so happy. It felt completely different to realize that what I had learned was actually useful.” P7: “What I did in the assembly was just fixing a small part but seeing that part working in the end made me really happy. It was the first moment I could say, ‘I did this.’” | 9/15 | |

| (iii) Memorability | P3: “No matter how many times we studied circuit connections for exams at the university; we would forget them. But what I struggled with in a real project is still in my mind. When you make a mistake and fix it, you don’t forget it.” P6: “A mistake I made in a budget analysis taught me a lot. I never forgot to check that point in the next three reports. That incident is etched into my memory.” | 9/15 | |

| 1.4. Professional Identity and Role Awareness | (i) Feeling like an Employee | P11: “I participated in the meetings about the software we were developing, just like everyone else. They didn’t differentiate—they included me in the whole process. That gave me a full understanding of the project from start to finish.” P12: “I was surprised when I was invited to the meeting. I was only expected to observe, but they asked for my opinion—and what I said was taken seriously. That’s when I truly felt I was part of the work.” | 10/15 |

| (ii) Taking Responsibility | P1: “The deadline for the project presentation was fixed. We had to finish it on time. Unlike in classes, there were no extensions. It felt like a real job responsibility.” P5: “Mixing the samples was easy, but it could affect the entire outcome. If I hadn’t been careful, the whole process would have been ruined. It was stressful, but also very instructive for me.” | 9/15 | |

| (iii) Role Integration within the Team | P3: “At first, it wasn’t clear who was doing what. But once it was established that I was in charge of testing the electrical circuits, things changed. The team began to recognize me in that role—and I started to recognize myself that way, too.” P6: “I was organizing the meetings. I handled scheduling and content sharing. Because of that, the team didn’t just see me as a student, but as someone who coordinated the work.” | 8/15 | |

| 1.5. Career Orientation and Transformative Awareness | (i) Discovery of Vocational Interest/Disinterest | P5: “I realized that lab work wasn’t as suitable for me as I had thought. I found that I’m more drawn to dynamic jobs that involve social interaction.” P14: “At first, it seemed like an interesting job, but when I got into the application, I realized it didn’t appeal to me. Office work wasn’t as satisfying as I had expected.” | 10/15 |

| (ii) Clarification of Future Plans | P3: “I kept wondering whether system design or software was more suitable for me. Here, I worked mainly on hardware, but I felt more comfortable in software. Now I want to move in that direction.” P6: “I was torn between marketing and finance. Here, I worked with the marketing team, and I’ve made my decision—this field suits me better.” | 8/15 | |

| (iii) Development of Self-Awareness | P2: “I realized I need to be more open in communication. I used to get defensive when receiving feedback—now I’m learning to manage that.” P9: “I got really excited—and even a bit anxious—during my first interaction with a client. I love this field, but I realized I need to improve my stress management.” | 9/15 |

| Sub-Themes | Codes | Representative Quotes | Frequency (n = 15) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2.1. Technical and Psychosocial Guidance from the Mentor | (i) Task-Oriented Guidance | P3: “I didn’t know the proper sequence for setting up the circuit. But my mentor broke the tasks into parts and explained each one. That allowed me to complete them step by step.” P8: “The task I was given at first was very difficult. I didn’t know what to do. My mentor showed me step by step, and then I started to gain confidence.” | 9/15 |

| (ii) Encouragement to Ask Questions | P5: “In books, I just read and moved on, but here, asking a question and getting a direct answer was completely different. My mentor always said, ‘If you don’t ask, you can’t learn.’” P10: “My mentor always said, ‘Say it when you don’t understand.’ When I asked questions, he never reacted negatively—he just explained. That was really valuable.” | 10/15 | |

| (iii) Support for Self-Confidence | P6: “My mentor didn’t answer questions directly. When he said, ‘You decide,’ I hesitated at first. But when I saw that the decision I made actually worked, my confidence grew.” P8: “At first, I wanted to avoid the task. I kept thinking, ‘I can’t do this.’ But my mentor kept saying, ‘You can handle this,’ and it really encouraged me. I actually started believing in myself.” | 9/15 | |

| 2.2. The Mentor as a Role Model | (i) Observation of Professional Behavior | P3: “There was a problem just hours before the project was due. Everyone was panicking, but our mentor stayed completely calm. That attitude was very instructive for me.” P12: “I began to see my mentor not just as an instructor but as someone to look up to. His attitude in meetings and the way he gave feedback taught me a lot.” | 8/15 |

| (ii) Behavioral Modeling | P9: “My mentor’s eye contact, tone of voice, and the way he asked questions stuck with me. I’ve started using those same things myself.” P11: ”My mentor always worked in small steps and would go back when there were errors. Now I code the same way—thinking like he does.” | 9/15 | |

| (iii) Aspiration to Assume Similar Roles | P2: “When she talked about her career journey, I was deeply inspired. Now I can clearly see what I need to do to become a systems engineer like her.” P11: “She had founded her own startup—she was both technical and visionary. I want to be an entrepreneur too. She really inspired me to follow a path like hers.” | 10/15 | |

| 2.3. Trust and Openness in the Mentoring Relationship | (i) Open Communication | P2: “My mentor was very approachable. I never felt like I had to be overly formal. That made it easier to ask questions and helped me improve myself.” P4: “I made a mistake in the code, but instead of getting upset, my mentor asked why I thought it happened. That helped me become more open about my mistakes.” | 10/15 |

| (ii) Emotional Safety | P3: “I used to want to hide my mistakes, but my mentor’s approach was so supportive. Now I show what I’ve done without fear, because I know I won’t be blamed.” P11: “There were times I completely froze while coding. But when my mentor said, ‘We’ll look at it together, don’t worry,’ I felt so relieved. That kind of support meant a lot.” | 9/15 | |

| (iii) Learning without Judgment | P4: “I used to be afraid of admitting mistakes. But here, my mentor treated them as a natural part of the process, and that made learning much easier for me.” P8: “I repeated the same coding error a few times. But instead of scolding me, my mentor said, ‘Take another look—what might you have missed?’ That helped me accept the mistake and work through it.” | 9/15 | |

| 2.4. The Relationship between Mentorship and Career Orientation | (i) Career Guidance | P3: “After my conversations with my mentor, I decided which area I wanted to work in. I was uncertain before, but their guidance really gave me direction.” P11: “My mentor was a technical lead. After talking with her, I realized I wasn’t just interested in coding—I was also interested in team leadership. She helped me see that.” | 10/15 |

| (ii) Raising Awareness | P2: “After a meeting, my mentor said, ‘You communicate well with people—you should make use of that.’ I wasn’t even aware of it.” P5: “My mentor told me, ‘Your technical skills are strong, but you need to work on your analytical thinking.’ That sentence was a turning point for me—I had never questioned that part of myself before.” | 9/15 | |

| (iii) Offering Alternative Pathways | P4: “I had always thought of working in corporate companies, but my mentor talked about her startup experience. That sparked my interest in that area too.” P6: “Working abroad had never crossed my mind. My mentor suggested a few programs, and once I looked into them, I got really interested. Now I’m preparing for that path.” | 8/15 |

| Sub-Themes | Relevant SDGs |

|---|---|

| Transfer of Theoretical Knowledge into Practice | SDG 4.4—Technical and vocational skills |

| Deepening of Learning through Experience | SDG 4.7—Experiential and reflective learning |

| Concretization and Retention of Learning | SDG 4.1—Effective learning outcomes SDG 4.7—Meaningful, learner-centered education |

| Professional Identity and Role Awareness | SDG 8.6—Youth not in education, employment or training (NEET) |

| Career Orientation and Transformative Awareness | SDG 8.b—Youth employment strategies |

| Sub-Themes | Relevant SDGs |

|---|---|

| Technical and Psychosocial Guidance from the Mentor | SDG 4.7—Supportive, inclusive learning approaches |

| The Mentor as a Role Model | SDG 4.5—Equal opportunities through mentorship |

| Trust and Openness in the Mentorship | SDG 4.a—Safe, nonjudgmental learning environments |

| Relationship between Mentorship and Career Orientation | SDG 8.6—Career planning for youth SDG 8.b—Youth-oriented labor market |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

İlhan, Ü.D.; Duran, C. Talent Development in Science and Technology Parks (STPs) Within the Context of Sustainable Education Systems: Experiential Learning and Mentorship Practices in a Phenomenological Study. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5637. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125637

İlhan ÜD, Duran C. Talent Development in Science and Technology Parks (STPs) Within the Context of Sustainable Education Systems: Experiential Learning and Mentorship Practices in a Phenomenological Study. Sustainability. 2025; 17(12):5637. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125637

Chicago/Turabian Styleİlhan, Ümit Deniz, and Cem Duran. 2025. "Talent Development in Science and Technology Parks (STPs) Within the Context of Sustainable Education Systems: Experiential Learning and Mentorship Practices in a Phenomenological Study" Sustainability 17, no. 12: 5637. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125637

APA Styleİlhan, Ü. D., & Duran, C. (2025). Talent Development in Science and Technology Parks (STPs) Within the Context of Sustainable Education Systems: Experiential Learning and Mentorship Practices in a Phenomenological Study. Sustainability, 17(12), 5637. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125637