Evaluating the Dynamic Effects of Environmental Taxation and Energy Transition on Greenhouse Gas Emissions in South Africa: An Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Theoretical Framework

- Energy Transition Theory

1.2. Research Objectives

- To examine the long-run and short-run effects of environmental tax, coal consumption, and renewable energy consumption use on GHG emissions.

- To determine whether these instruments support the country’s energy transition goals.

- To provide evidence-based policy recommendations to enhance environmental and economic outcomes.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Impact of Environmental Tax on Greenhouse Gas Emissions

2.2. Impact of Renewable Energy Consumption on Greenhouse Gas Emissions

2.3. Impact of Coal Consumption on Greenhouse Gas Emissions

2.4. Impact of Net Energy Imports on Greenhouse Gas Emissions

3. Data and Methods

3.1. Data Sources

3.2. Model Specification

3.2.1. Data Processing and Transformation

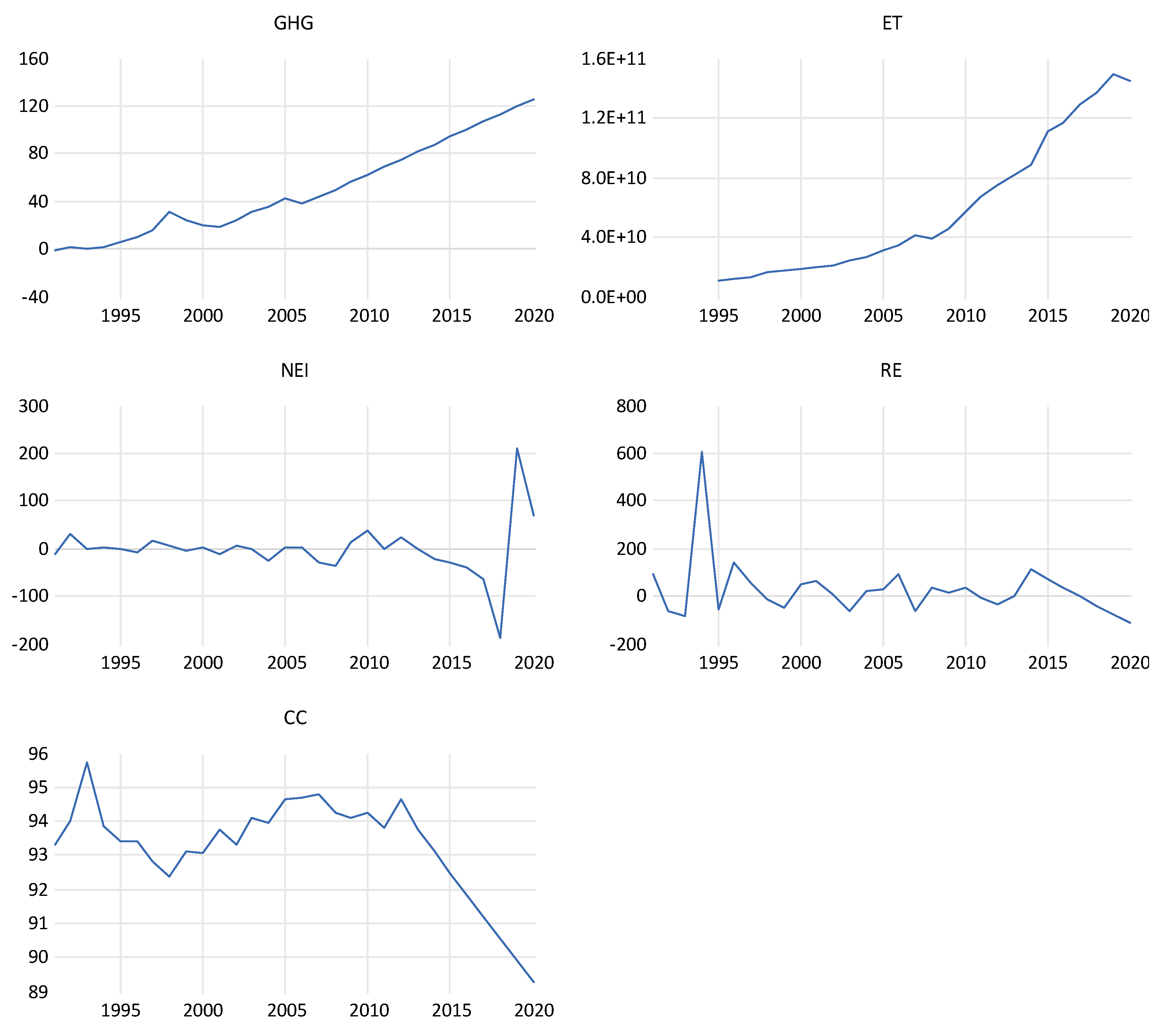

- Greenhouse Gas Emissions (GHG): Quantified in kilotons of CO2-equivalent, the original data were sourced from the World Bank database. No changes were made to maintain clarity in levels.

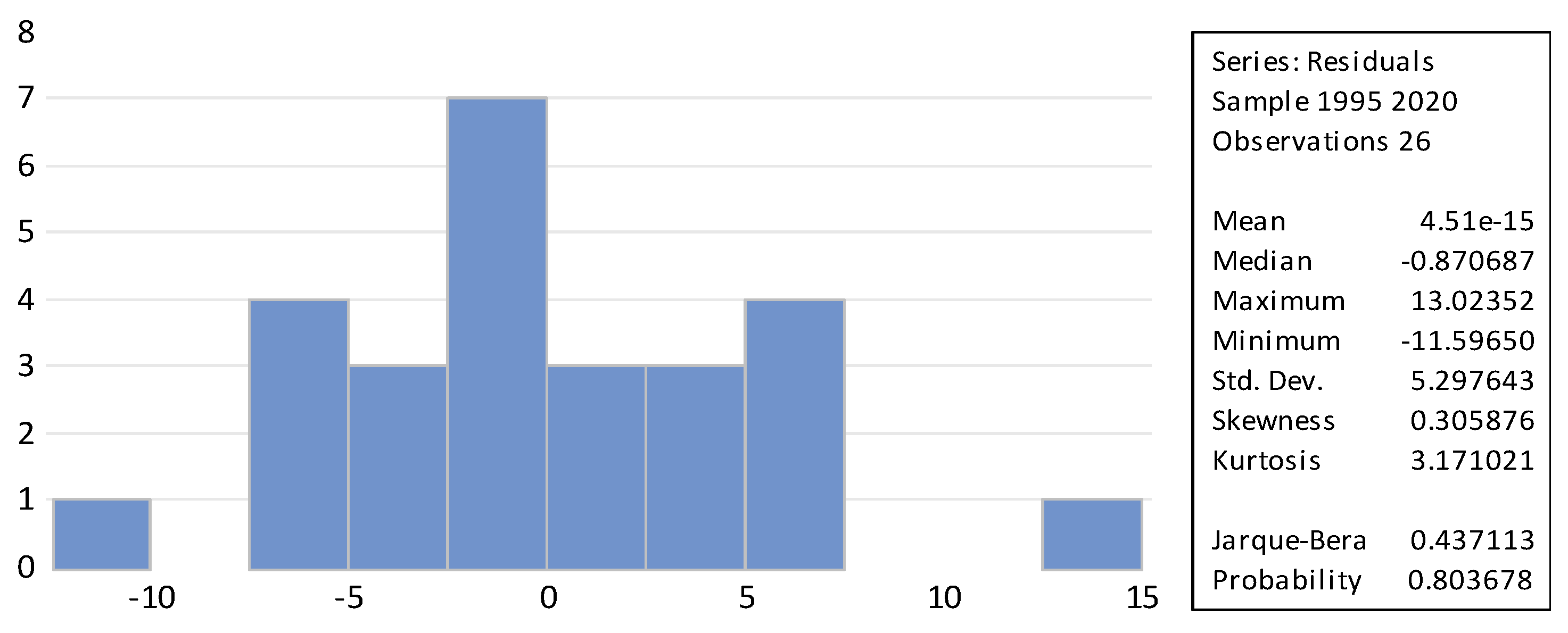

- Environmental Tax Revenue (ET): This variable reflects the overall tax income generated from environmental tax tools, stated in nominal South African rand. Because of the existence of zero and near-zero values in the initial years of the sample (1995–1999), logarithmic transformation was not utilized. Utilizing log transformations in these instances would require incorporating arbitrary constants (e.g., log (ET + 1)), potentially skewing estimation outcomes and affecting economic interpretability [38]. According to the descriptive statistics (Section 4.2), the ET series exhibits positive skewness (skewness = 0.7485), indicating a lengthy right tail frequently seen in fiscal and revenue-related metrics. Although ARDL estimation is typically resilient to non-normal regressors, we recognize the possible effects on finite-sample inference and tackle this by conducting post-estimation residual diagnostics. Specifically, Jarque–Bera tests for normality on the model residuals validate normality (p = 0.8037), confirming that the skewness of the regressor does not affect the reliability of the t-statistics or F-tests applied in inference.

- Net Energy Import (NEI): Defined as the gap between energy imports and exports, NEI measures South Africa’s reliance on foreign energy sources. A favorable NEI signifies being a net energy importer, showing a dependence on external fuel sources. This variable holds theoretical significance as it reflects the indirect influence of energy trade on emissions via fuel mix composition, energy pricing, and technological spillovers. Although greater imports of cleaner fuels might lower emissions, dependence on imported fossil fuels or inefficiencies in energy conversion methods could worsen emissions. Therefore, the anticipated sign is theoretically unclear and reliant on context. Due to the existence of negative values (indicating net exports in specific years), log transformation was not possible; the series was kept in its original form and differenced according to stationarity results.

- Renewable Energy Consumption (RE): This variable measures the overall yearly usage of renewable energy (in GWh), including sources like solar, wind, hydroelectric, biomass, and geothermal energy. It was obtained from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators and indicates total renewable energy deployment instead of its proportional share. Due to its non-stationary characteristics in level form and in line with ARDL model prerequisites, the RE variable underwent a transformation through first differencing, thus quantifying the variation in renewable energy consumption from one year to the next. This differencing resulted in the appearance of both positive and negative values, which align conceptually with yearly rises and falls in renewable energy adoption.

- Coal Consumption (CC): Expressed in million tonnes of oil equivalent (Mtoe), these data were utilized in its original form without alteration, due to the fairly consistent variance. The normality of the distribution was evaluated, and first differencing was conducted as required based on the results of unit root tests.

3.2.2. Justification and Description of Variables

- NEI is expected to exert a negative effect, assuming imports replace domestically produced carbon-intensive energy sources; however, effects may be ambiguous in the case of fossil fuel-dominated imports.

3.3. Estimation Strategy and Diagnostic Test

3.3.1. Unit Root Tests

3.3.2. Optimal Lag Selection

3.3.3. Bounds Test

3.3.4. Estimating Short-Run Coefficients

3.3.5. Research Reliability and Validity

3.3.6. Post-Test/Diagnostics

- Normality Test

- Multicollinearity

- Heteroskedasticity

- Serial Correlation

- Ramsey Test

- Stability Test

3.4. Model Assumptions and Limitations

4. Findings and Discussion

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Preliminary Tests

4.2.1. A Stationarity Test

- Visual Inspection

4.2.2. Expanded Presentation of Unit Root Tests

Interpretation

4.3. Determination of Optimal Lag Length

- Interpretation and Justification

4.4. ARDL Bounds Testing Result

4.4.1. ARDL Bounds Testing Result

4.4.2. Long-Run Estimates

- Long-Run Interpretation

- Environmental Taxes (ETs)

- Net Energy Imports (NEIs)

- Renewable Energy Consumption (RE)

- Coal Consumption (CC)

- Short-Run Coefficients (Table 7)

| Dependent Variable: GHG | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Included Observations: 26 | ||||

| ECM Short-Run Dynamic ARDL Estimation | ||||

| Variable | Coefficient | Std. Error | t-Statistic | Prob. |

| D(CC) (coal consumption) | −1.7301 | 1.4998 | −1.4998 | 0.2630 |

| CointEq (−1) | −0.2799 | 0.0471 | −5.9452 | 0.0000 |

- Short-Run Estimates

- Coal Usage (Short-run)

- Error CorrectionTerm (ECT)

4.5. Post-Test Results (Diagnostic Tests)

- NormalityTest (Jarque–Bera Test and Figure 2)

- Heteroskedasticity (Breusch–Pagan–Godfrey Test)

- Serial Correlation (Breusch–Godfrey LM Test)

- Multicollinearity(Variance Inflation Factor—VIF)

- Specification Test (Ramsey RESET Test)

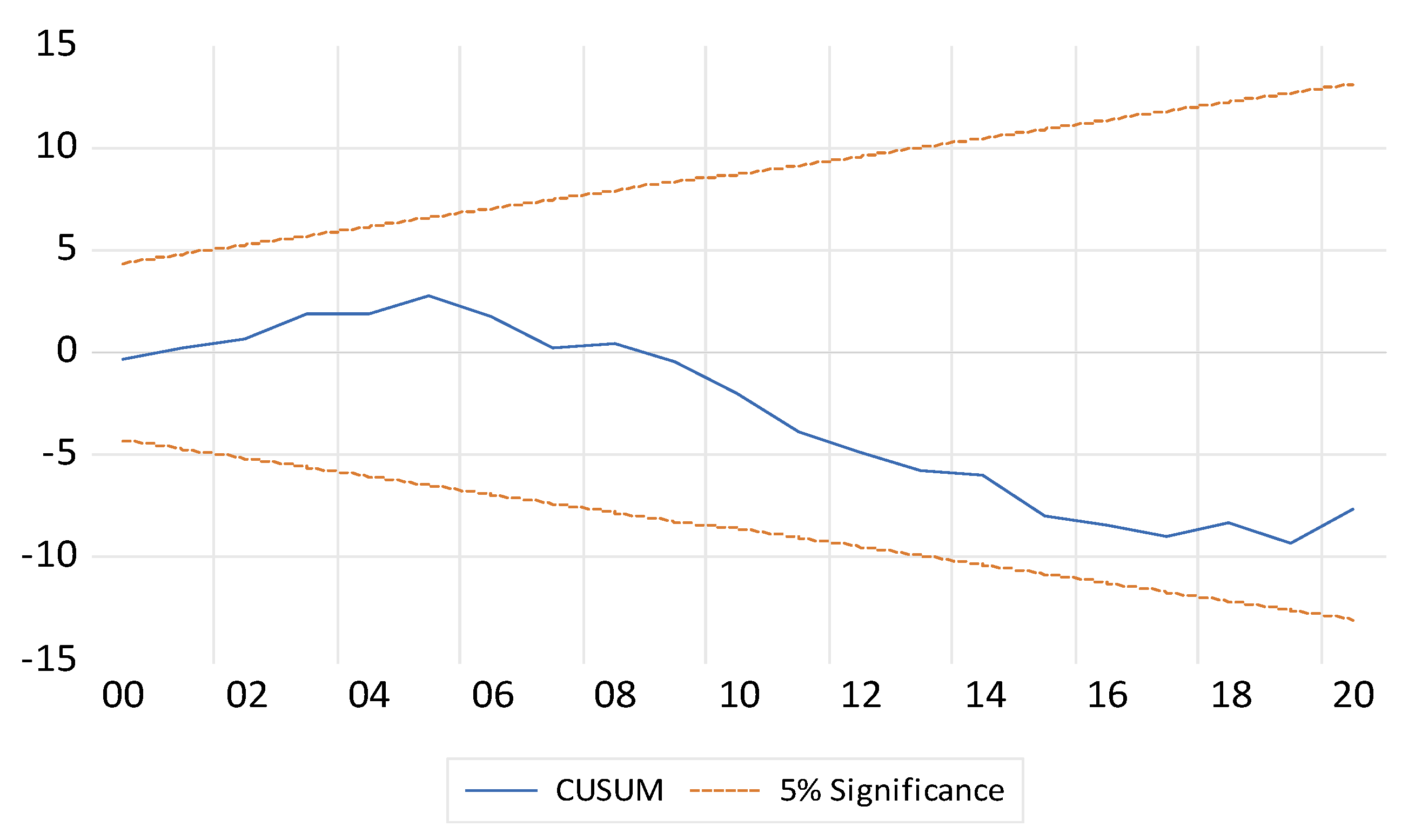

- Stability Test (CUSUM Chart, Figure 3)

- Validation of Models and Diagnostics for Robustness

- Policy and Academic Implications

4.6. Conclusions

5. Summary of Key Findings and Policy Recommendation

5.1. Summary of Key Findings

- Environmental Taxation: An Incoherent Fiscal Instrument

- Net Energy Imports: Slight Direct Effect

- Renewable Energy: Limited Emissions Effectiveness

- Coal Usage: A Continuing Emissions Catalyst

- Short-Term Irrelevance, Long-Term Consistency

5.2. Policy Recommendations

- Short-Term Priorities (0–5 years)

- Adjustment of the Carbon Tax Structure

- Action: Remove exemptions for carbon-heavy industries and adjust the tax rate to match the marginal abatement cost.

- Institutional Responsibility: National Treasury and South African Revenue Service (SARS).

- Anticipated Effect: Enhance the price indication for lowering emissions and produce funds for eco-friendly investments.

- System for Monitoring Digital Emissions

- Initiative: Create a nationwide, real-time digital system for monitoring sector-specific GHG emissions.

- Institutional Accountability: Department of Forestry, Fisheries, and the Environment (DFFE), collaborating with CSIR.

- Anticipated Effect: Improve regulatory supervision and clarity in emissions reporting.

- Focused Green Industrial Benefits

- Action: Broaden incentive programs (e.g., Section 12L of the Income Tax Act) for local manufacturing of solar panels, electrolyzers, and grid parts.

- Institutional Accountability: Department of Trade, Industry and Competition (DTIC); Industrial Development Corporation (IDC).

- Anticipated Outcome: Boost local eco-friendly production and lessen reliance on technology imports.

- Coal Transition Area Investment Initiative

- Action: Initiate retraining programs and support funds for SMEs in Mpumalanga and other areas dependent on coal.

- Institutional Accountability: Department of Employment and Labour; Presidential Climate Commission.

- Anticipated Outcome: Alleviate workforce dislocation and encourage local economic variety.

- Measures for Long-Term Structure (5–15 years)

- Integrated Renewable Energy Implementation

- Action: Increase public–private investments in renewable energy via competitive auctions and power purchase agreements (PPAs), in accordance with the IRP.

- Institutional Responsibility: Department of Mineral Resources and Energy (DMRE); Eskom; Office of Independent Power Producers (IPPOs).

- Anticipated Outcome: Lower carbon emissions from electricity production and decrease Eskom’s carbon intensity.

- Grid Update and Connectivity

- Action: Enhance and broaden the national transmission network to facilitate decentralized renewable energy production.

- Institutional Accountability: Eskom Transmission Company; National Energy Regulator of South Africa (NERSA).

- Anticipated Effect: Mitigate transmission bottlenecks and enhance renewable grid integration.

- Formation of an Energy Transition and Climate Finance Agency

- Action: Organize concessional and blended financing for decarbonization, encompassing JET-IP alignment and global green bonds.

- Responsibility of Institutions: National Treasury; DBSA; Task Team for Presidential Climate Finance.

- Anticipated Outcome: Generate sustained investment for infrastructure related to mitigation and adaptation.

5.3. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Satgar, V. The climate crisis and systemic alternatives. In The Climate Crisis: South African and Global Democratic Eco-Socialist Alternatives; Wits University Press: Johannesburg, South Africa, 2018; pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Sasu, D.D. Africa: CO2 Emissions by Country. 2024. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1268395/production-based-co2-emissions-in-africa-by-country/ (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Hanto, J.; Schroth, A.; Krawielicki, L.; Oei, P.Y.; Burton, J. South Africa’s energy transition–unraveling its political economy. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2022, 69, 164–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- South African Revenue Service. Carbon Tax. 2023. Available online: https://www.sars.gov.za/customs-and-excise/excise/environmental-levy-products/carbon-tax/ (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Vuzane, R. An Analysis of Carbon Tax and Other Environmental Levies: A South African and International Perspective. Master’s Dissertation, Rhodes University, Grahamstown, South Africa, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Errendal, S.; Ellis, J.; Jeudy-Hugo, S. The Role of Carbon Pricing in Transforming Pathways to Reach Net Zero Emissions: Insights from Current Experiences and Potential Application to Food Systems; OECD: Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Nene, S.; Nagy, H. Legal regulations and policy barriers to development of renewable energy sources in South Africa. In Engineering for Rural Development, Proceedings of the International Scientific Conference (Latvia) (No. 20), Jelgava, Latvia, 26–28 May 2021; Latvia University of Life Sciences and Technologies: Jelgava, Latvia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ndlovu, V.; Inglesi-Lotz, R. The causal relationship between energy and economic growth through research and development (R&D): The case of BRICS and lessons for South Africa. Energy 2020, 199, 117428. [Google Scholar]

- Adepeju, I.Z. Managing Climate Risks in Africa: Insights from South Africa and Ethiopia. Doctoral Dissertation, Memorial University of Newfoundland, St. John’s, NL, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change). Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis; Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Burke, M.J.; Stephens, J.C. Political power and renewable energy futures: A critical review. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2018, 35, 78–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smil, V. Energy in World History; Routledge: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson, M.Z.; Delucchi, M.A.; Bauer, Z.A.; Goodman, S.C.; Chapman, W.E.; Cameron, M.A.; Yachanin, A.S. 100% clean and renewable wind, water, and sunlight all-sector energy roadmaps for 139 countries of the world. Joule 2017, 1, 108–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onofrei, M.; Vintilă, G.; Dascalu, E.D.; Roman, A.; Firtescu, B.N. The impact of environmental tax reform on greenhouse gas emissions: Empirical evidence from european countries. Environ. Eng. Manag. J. (EEMJ) 2017, 16, 2843–2849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotnik, Ž.; Maja, K.; Škulj, D. The effect of taxation on greenhouse gas emissions. Transylv. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2014, 10, 168–185. [Google Scholar]

- Rybak, A.; Joostberens, J.; Manowska, A.; Pielot, J. The impact of environmental taxes on the level of greenhouse gas emissions in Poland and Sweden. Energies 2022, 15, 4465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Qin, D. Sustainable mining and the role of environmental regulations and incentive policies in BRICS. Resour. Policy 2024, 90, 104718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarfraz, M.; Ivascu, L.; Cioca, L.I. Environmental regulations and CO2 mitigation for sustainability: Panel data analysis (PMG, CCEMG) for BRICS nations. Sustainability 2021, 14, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisdom, O.; Apollos, N.; Samuel, O. Carbon accounting and economic development in sub-Saharan Africa. Asian J. Econ. Bus. Account. 2022, 22, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.K.; Zhang, X. Firm’s imperfect compliance and pollution emissions: Theory and evidence from South Africa. Asian J. Econ. Bus. Account. 2019, 1, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, M.; Sati, M.; Uniyal, S. Impact of Renewable Energy in Reducing Greenhouse Gas Emissions. In Renewable Energy and Green Technology; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2021; pp. 127–139. [Google Scholar]

- Mandimby, A.S. Effect of Renewable Energi on CO2 Emissions in BRICS Countries. Quant. Econ. Manag. Stud. 2024, 5, 372–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riti, J.S.; Riti, M.K.J.; Oji-Okoro, I. Renewable energy consumption in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA): Implications on economic and environmental sustainability. Curr. Res. Environ. Sustain. 2022, 4, 100129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocak, E.; Ulug, E.E.; Oralhan, B. The impact of electricity from renewable and non-renewable sources on energy poverty and greenhouse gas emissions (GHGs): Empirical evidence and policy implications. Energy 2023, 272, 127125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ismail, F.S.; Alam, M.S.; Shafiullah, M.; Hossain, M.I.; Rahman, S.M. Impacts of renewable energy generation on greenhouse gas emissions in Saudi Arabia: A comprehensive review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziuku, S.; Meyer, E.L. Mitigating climate change through renewable energy and energy efficiency in the residential sector in South Africa. Int. J. Renew. Energy Technol. 2012, 2, 33–43. [Google Scholar]

- Ayodele, T.R.; Munda, J.L. The potential role of green hydrogen production in the South Africa energy mix. J. Renew. Sustain. Energy 2019, 11, 044301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, A.; Lan, J.; Lenzen, M. Trends in global greenhouse gas emissions from 1990 to 2010. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 4722–4730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.; Rahman, Z.U.; Zhang, X.; Islam, M.S. An assessment of the effect of green innovation, income, and energy use on consumption-based CO2 emissions: Empirical evidence from emerging nations BRICS. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 365, 132636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guedie, R.; Ngnemadon, A.S.A.; Fotio, H.K.; Nembot, L. Disaggregated analysis of the effects of energy consumption on greenhouse gas emissions in Africa. Energy Econ. Lett. 2022, 9, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, N.C.; Saha, D. Impact of coal mining on ambient air in respect of global warming: A critical approach. Indones. J. Soc. Environ. Issues (IJSEI) 2023, 4, 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Song, X.; Liu, Y. China’s coal consumption in a globalizing world: Insights from Multi-Regional Input-Output and structural decomposition analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 711, 134790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, J.; Yang, F.; Xu, Y. Coal consumption and carbon emission reductions in BRICS countries. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0300676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adebayo, T.S.; Kirikkaleli, D.; Adeshola, I.; Oluwajana, D.; Akinsola, G.D.; Osemeahon, O.S. Coal consumption and environmental sustainability in South Africa: The role of financial development and globalization. Int. J. Renew. Energy Dev. 2021, 10, 527–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekun, F.V.; Etokakpan, M.U.; Agboola, M.O.; Uzuner, G.; Wada, I. Modelling coal energy consumption and economic growth: Does asymmetry matter in the case of South Africa? Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2023, 32, 2029–2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadorsky, P. Trade and energy consumption in the Middle East. Energy Econ. 2011, 33, 739–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omri, A.; Nguyen, D.K. On the determinants of renewable energy consumption: International evidence. Energy 2014, 72, 554–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghvaee, V.M.; Hajiani, P.; Aloo, A.S. Elasticities of Energy, Environment, and Economy in Long and Short Run: Using Simultaneous Equations, Error Correction and Cointegration Models. J. Emerg. Issues Econ. Financ. Bank. 2017, 6, 2155–2186. [Google Scholar]

- Gujarati, D.N. Basic Econometrics, 4th ed.; Tata McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ibeabuchi, I.J.; Amaefule, C.; Shoaga, A. Determinants of greenhouse gas emissions. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. Res. 2022, 6, em0194. [Google Scholar]

- Michel, B.; Falcao, T. OECD (2022) Public Consultation on Pillar One–Amount A: Draft Model Rules for Nexus and Revenue Sourcing: Comments by B. Michel and T. Falcao. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4266352 (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Aldy, J.E.; Stavins, R.N. Using the market to address climate change: Insights from theory & experience. Daedalus 2012, 141, 45–60. [Google Scholar]

- Paavo, E. The Impact of Commercial Banks Development on Economic Growth in Namibia. Master’s Thesis, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Yakubu, Y.; Salisu, B.M.; Umar, B. Electricity supply and manufacturing output in Nigeria: Autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) Bound testing approach. J. Econ. Sustain. Dev. 2015, 6, 7–19. [Google Scholar]

- Liew, V. On Autoregressive Order Selection Criteria. Master’s Thesis, Universiti Putra Malysia, Serdang, Malaysia, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Demirhan, H. dLagM: An R package for distributed lag models and ARDL bounds testing. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0228812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asteriou, D.; Hall, S.G. Applied Econometrics; Bloomsbury Publishing: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ogujiuba, K.; Mngometulu, N. Does social investment influence poverty and economic growth in South Africa: A cointegration analysis? Economies 2022, 10, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fullerton, D.; Metcalf, G.E. Tax Incidence; National Bureau of Economic: Cambridge, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Woolridge, J.M. Introductory Econometrics: A Modern Approach; South Western Cengage Learning: Mason, OH, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Abbreviation | Description | Expected Sign | Units | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Greenhouse Gas Emissions | GHG | Total greenhouse gas emissions in kilotonnes of CO2 equivalent, encompassing anthropogenic CO2, CH4, N2O, and F-gases (HFCs, PFCs, and SF6), excluding short-cycle biomass burning. | Dependent | Kt CO2 | World Bank |

| Environmental Tax Revenue | ETAX | Revenue from taxes where the base is a physical unit or proxy with a negative environmental impact (e.g., carbon content, fuel volume). It reflects fiscal instruments aimed at curbing pollution and incentivizing cleaner behavior. | Negative (–) | Local Currency Units | IMF (via OECD/UNEP databases) |

| Net Energy Imports | NEI | Net imports of energy (in oil equivalents) capture structural reliance on foreign energy sources, affecting emissions via energy mix, security, and pricing. | Negative (–) | % of energy use | World Bank |

| Renewable Energy Consumption | RE | Total renewable energy consumption in physical units (e.g., GWh), not as a share | Negative (–) | GWh or % points | World Bank |

| Coal Consumption | COAL | Total consumption of coal (primary and derived), including hard coal, lignite, and peat, used mainly in power generation. Coal is a major driver of carbon emissions due to its high carbon intensity. | Positive (+) | Million tonnes oil equivalent (Mtoe) | World Bank |

| Statistic | GHG | ET | NEI | RE | CC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 57.1000 | 5.88 × 1010 | −3.2512 | 9.7349 | 93.0960 |

| Median | 46.9545 | 4.00 × 1010 | −1.3725 | 13.8956 | 93.4070 |

| Maximum | 125.9758 | 1.49 × 1011 | 211.8577 | 142.2365 | 94.7701 |

| Minimum | 6.3425 | 1.09 × 1010 | −189.3993 | −115.3336 | 89.2494 |

| Std. Dev. | 36.8137 | 4.64 × 1010 | 62.5476 | 61.6073 | 1.4847 |

| Skewness | 0.4212 | 0.7485 | 0.5954 | 0.0767 | −1.1647 |

| Kurtosis | 1.8876 | 2.1235 | 9.2140 | 2.5906 | 3.5695 |

| Jarque–Bera | 2.1093 | 3.2600 | 43.3677 | 0.2071 | 6.2302 |

| Probability | 0.3483 | 0.1959 | 0.0000 | 0.9016 | 0.0444 |

| Sum | 1484.599 | 1.53 × 1012 | −84.5303 | 253.1077 | 2420.495 |

| Sum Sq. Dev. | 33,881.29 | 5.39 × 1022 | 97,805.06 | 94,886.46 | 55.10883 |

| Observations | 26 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 26 |

| Variable | Model Specification | ADF | PP | Order of Integration | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Levels | First Difference | Levels | First Difference | |||

| GHG | Intercept and trend | 0.0148 *** | 0.3033 | 0.9158 | 0.0000 *** | 1 |

| Intercept | 0.9998 | 0.0006 *** | 1.0000 | 0.0006 *** | 1 | |

| ET | Intercept and trend | 0.8232 | 0.0056 *** | 0.8254 | 0.0056 *** | 1 |

| Intercept | 0.9997 | 0.0140 *** | 0.9997 | 0.0120 *** | 1 | |

| NEI | Intercept and trend | 0.0000 *** | 0.0000 *** | 0.0000 *** | 0.0000 *** | 1 and 0 |

| Intercept | 0.0000 *** | 0.0000 *** | 0.0000 *** | 0.0000 *** | 1 and 0 | |

| RE | Intercept and trend | 0.0000 *** | 0.0000 *** | 0.0000 *** | 0.0001 *** | 1 and 0 |

| Intercept | 0.0000 *** | 0.0000 *** | 0.0000 *** | 0.0001 *** | 1 and 0 | |

| CC | Intercept and trend | 0.9886 | 0.0002 *** | 0.9654 | 0.0002 *** | 1 |

| Intercept | 0.9688 | 0.0021 *** | 0.9759 | 0.0001 *** | 1 | |

| Lags | LogL | LR | FPE | AIC | SC | HQ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | −1032.191 | NA | 7.47 × 1029 | 82.9753 | 83.21908 * | 83.04291 |

| 1 | −929.4702 | 156.1359 * | 1.56 × 1027 * | 76.75762 * | 78.22027 * | 77.16330 * |

| Test Statistic | Value | Signif. | I(0) | I(1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F-statistic | 4.6636 | 10% | 2.2 | 3.09 |

| K | 4 | 5% | 2.56 | 3.49 |

| 2.5% | 2.88 | 3.87 | ||

| 1% | 3.29 | 4.37 |

| Dependent Variable: GHG | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Included Observations: 26 | ||||

| Long-Run Coefficients Using the ARDL | ||||

| Variable | Coefficient | Std. Error | t-Statistic | Prob. |

| ET | 9.01 × 10−10 | 1.04 × 10−10 | 8.6749 | 0.0000 |

| NEI | 0.0089 | 0.0502 | 0.1776 | 0.8609 |

| RE | −0.0722 | 0.0711 | −1.0146 | 0.3230 |

| CC | 6.6656 | 3.9499 | 1.6875 | 0.1079 |

| C | −605.6720 | 367.2469 | −1.6492 | 0.1155 |

| Normality Test | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| If the p-value is below 0.05, we reject the null hypothesis, which assumes that the residuals are normally distributed in normality testing. In this model, the probability of 0.80 exceeds the significance level of 0.05, leading us to not reject the null hypothesis. | |||

| Multicollinearity | |||

| Variable | Centered VIF | ||

| ET | 2.1494 | ||

| NEI | 1.0630 | ||

| RE | 1.2068 | ||

| CC | 2.2746 | ||

| The null hypothesis is rejected since all values under VIF are less than 5; therefore, there is no multicollinearity. | |||

| Heteroskedasticity | |||

| F-statistic | 1.2272 | Prob. F(4.38) | 0.3294 |

| Obs. * R-square | 4.9260 | Prob. Chi-square (4) | 0.2950 |

| Scaled explained SS | 3.4884 | Prob. Chi-square (4) | 0.4797 |

| Therefore, since the chi-square probability is 0.2950, which exceeds the 0.05 significance level, the null hypothesis cannot be refuted, indicating that the variances in the model remain consistent. Note: Asterisks in the regression tables denote statistical significance levels at p < 0.1 (), p < 0.05 (), and p < 0.01 (), respectively. | |||

| Serial Correlation | |||

| F-statistic | Durbin–Watson statistic | Observed R-Squared | Prob. chi-square |

| 0.8846 | 1.5 | 0.2.2147 | 0.3304 |

| In this case, the R-square p-value of 0.3304 exceeds the 5 percent significance level, indicating that the null hypothesis of no autocorrelation cannot be disproved. | |||

| Stability Test | |||

| The CUSUM test is applied to check the stability of the estimated parameters of the model. The result from the CUSUM reveals that the estimated lines are within the critical limits of the 5% level of significance. Therefore, it is confirmed that the variables of the estimated model remained stable during the sample period of the study. | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kanayo, O.; Maponya, L.; Semenya, D. Evaluating the Dynamic Effects of Environmental Taxation and Energy Transition on Greenhouse Gas Emissions in South Africa: An Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) Approach. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5531. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125531

Kanayo O, Maponya L, Semenya D. Evaluating the Dynamic Effects of Environmental Taxation and Energy Transition on Greenhouse Gas Emissions in South Africa: An Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) Approach. Sustainability. 2025; 17(12):5531. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125531

Chicago/Turabian StyleKanayo, Ogujiuba, Lethabo Maponya, and Dikeledi Semenya. 2025. "Evaluating the Dynamic Effects of Environmental Taxation and Energy Transition on Greenhouse Gas Emissions in South Africa: An Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) Approach" Sustainability 17, no. 12: 5531. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125531

APA StyleKanayo, O., Maponya, L., & Semenya, D. (2025). Evaluating the Dynamic Effects of Environmental Taxation and Energy Transition on Greenhouse Gas Emissions in South Africa: An Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) Approach. Sustainability, 17(12), 5531. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125531