1. Introduction

Sustainability has become a defining principle of the 21st century, symbolising the pursuit of a more equitable and prosperous society that preserves the environment and cultural heritage for future generations [

1]. At its core, sustainability means meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs [

2]. As the responsibility for sustainable development increasingly falls on all members of society, companies are expected to act responsibly, given their significant impact on environmental and social issues [

3,

4].

Corporate sustainability governance translates sustainable development principles into business practices, requiring companies to integrate environmental, social, and economic considerations into their operations [

5]. Despite the development of various sustainability frameworks, such as environmental management systems and sustainability reporting, their effectiveness often falls short, largely due to a lack of strategic orientation in implementing sustainability goals [

3,

6].

Achieving corporate sustainability requires balancing economic development, environmental protection, and social responsibility [

5,

7]. Corporate sustainability strategies are strategies aimed at balancing the social, environmental, and economic needs of both companies and society [

8]. They integrate social and environmental dimensions into the strategic management process and emphasise the strategic positioning of companies in terms of sustainable development [

3]. A strategic approach to sustainability management not only addresses these challenges but also offers companies a competitive advantage by capitalising on opportunities and minimising risks across the environmental, social, and economic pillars of sustainability [

9,

10,

11]. The strategic approach has gained traction in both the academic and business communities, emphasising the need to make sustainability an integral part of corporate strategy [

12,

13].

While considerable attention has been paid to the conceptual design of sustainability strategies, less focus has been placed on their practical implementation [

14]. For companies committed to sustainability, the key question now is not whether to implement sustainability strategies but how to implement them [

15]. Current research suggests a shift toward understanding the practicalities of implementation, with a need for empirical studies to explore this process within real-world settings [

12,

16,

17].

The objective of this research is to explore the critical success factors influencing the successful implementation of corporate sustainability strategies in production companies and to contribute to improved organisational practices and understanding of these processes. The focus on production companies is deliberate, as industrial organisations play a particularly significant role in the transition toward sustainability, given their substantial environmental and social impacts as well as their potential for systemic change [

3]. The contribution is the development of a taxonomy of critical success factors (CSFs) for implementing corporate sustainability strategies. This research addresses the following questions:

RQ1: What are the CSFs for implementing corporate sustainability strategies?

RQ2: What is the role of identified CSFs in the successful implementation of corporate sustainability strategies?

RQ3: What are the interrelationships between the identified CSFs?

This paper is structured into seven sections:

Section 1 is an introduction,

Section 2 outlines the theoretical foundation of the research, and

Section 3 details the adopted methodology.

Section 4 identifies the CSFs, introducing the taxonomy of the CSFs, whereas

Section 5 describes the interrelationships between the CSFs.

Section 6 discusses the results and

Section 7 provides the conclusions, academic and practical contributions, and suggestions for future work.

2. Theoretical Background

The concept of sustainable development was introduced to the broader public by the World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED), also known as the Brundtland Commission, in its report that defines sustainable development as development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs [

2]. Sustainable development encompasses three pillars—environmental, economic, and social—and is based on the idea that it is necessary to balance and integrate economic and socio-environmental goals to achieve long-term value creation for all stakeholders [

18].

Companies are increasingly at the center of the sustainability debate, as they are often seen as responsible for numerous negative impacts on the environment and society, and they play a key role in transitioning society towards sustainable development [

4]. To achieve sustainability, companies must implement the principles of sustainable development into their products, policies, and practices. Sustainability in companies is achieved at the intersection of economic success, environmental responsibility, and social responsibility [

7]. Corporate sustainability is a way for companies to address global challenges and accelerate sustainable development [

13]. The primary reason for adopting a sustainable approach is to reduce the negative environmental and social impacts of corporate activities while improving (or at least not diminishing) the economic performance of the company. Both the company itself and other businesses, nature, and society benefit from a company’s sustainable development [

3].

There is no universal definition of corporate sustainability, but it is generally understood as achieving positive economic, social, and environmental performance in the present without compromising the company’s future economic performance [

13]. Elkington has defined corporate sustainability as a triple responsibility of companies, being environmental, social, and economic responsibility, commonly referred to as the three Ps: people, planet, and prosperity [

19]. In their efforts towards sustainability, companies strive for balanced development in the economic, social, and environmental spheres [

20].

Meuer [

13] and colleagues identified 33 definitions of corporate sustainability and, through their analysis, explained the different understandings of the concept in academic circles. In summary, the various definitions of corporate sustainability most frequently relate to the four components derived from the definition of the WCED—consideration of future generations—or from the Triple Bottom Line (TBL) of corporate responsibility—economic, social, and environmental responsibility [

13].

Key elements can be distilled, including the balance between environmental, social, and economic aspects of business operations, consideration of stakeholders, and the simultaneous consideration of short-term and long-term impacts.

For the purposes of this research, we have established the following definition of corporate sustainability:

Corporate sustainability is the way in which companies operate to ensure long-term economic success and value creation through processes and activities that minimise negative impacts and maximise positive impacts on the environment and society, while maintaining a balance between short-term and long-term impacts.

The terms

corporate social responsibility and

ESG (an acronym for environmental, social, and governance) are often used synonymously with the term

corporate sustainability. All three terms have some similarities, but also some differences. Both corporate sustainability and social responsibility share a focus on the TBL. However, corporate sustainability is more strategic in nature, focusing on integrating sustainability into core business operations, while corporate social responsibility aims to ensure broader societal well-being, with less emphasis on embedding sustainability into core business functions. ESG, on the other hand, is a measurable approach that assesses the environmental, social, and governance aspects of companies, which is important for investors [

21,

22]. Another often-used term is

circular economy, which is more distinct. The circular economy focuses mainly on environmental aspects like waste reduction and resource efficiency, contributing to sustainable development. However, it is primarily concerned with environmental issues, rather than social and economic ones [

23].

This study is explicitly positioned within the domain of corporate sustainability. It addresses the strategic integration of sustainability into the governance, structures, and operations of organisations. Corporate commitment to sustainability has become increasingly relevant in both academic and business circles in recent years. Such a commitment to sustainable development requires a strategic approach that ensures that sustainability is an integral part of the company’s business strategy and processes [

12].

For companies, a strategic approach to sustainability management means securing the benefits of environmental and social investments [

9]. It involves developing a long-term competitive advantage that enables the company to capitalise on opportunities in all three areas of sustainability—environmental, social, and economic—while minimising risks in all three areas [

11]. Sustainability management is, therefore, a company’s strategic and profit-driven response to environmental and social issues arising from its operations [

10]. For these reasons, companies are increasingly recognising the need for strategic sustainability management to remain competitive [

1].

Corporate sustainability strategies are strategies aimed at balancing the social, environmental, and economic needs of both companies and society [

8]. They integrate social and environmental dimensions into the strategic management process and emphasise the strategic positioning of companies in terms of sustainable development [

3]. They involve the integration of sustainability goals into both short- and long-term strategic objectives and require alignment with the needs of internal and external stakeholders [

3]. Compared to conventional business strategies, sustainability strategies differ primarily in the inclusion of additional environmental and social factors, which increases complexity and requires broader stakeholder engagement. This complexity arises from the long-term nature of sustainability planning and the need to account for extended environmental and societal impacts, such as climate change and stakeholder expectations [

12,

24]. These strategies, however, can vary considerably in scope and orientation. Baumgartner and Ebner [

25] identify several distinct types—such as introverted, extroverted, conservative, and visionary strategies—which differ in how comprehensively sustainability is integrated into business activities and in the underlying motivation for engaging with sustainability. Some strategies focus primarily on compliance and risk avoidance, while others pursue sustainability as a driver of innovation and long-term competitive advantage [

25].

Based on a review of the literature on strategic sustainability management conducted by Engert and colleagues [

12] from 1991, when the first contributions to this field began to emerge, to 2013, and based on a review of the literature on strategic sustainability management conducted by Nguyen and colleagues [

16] from 2016 to 2022, we find that the number of contributions started to increase after 2007 [

12] and continued to grow after 2016 [

16] indicating increasing interest in this field.

Scientific contributions to the field of strategic sustainability management are mostly based on the classical approach to strategic management research, supplemented by specific insights from the field of sustainability [

14]. Although the importance of developing a sustainability strategy is widely recognised, little attention has so far been paid to its implementation. Most research still focuses on conceptual design rather than practical implementation [

14]. For companies that have decided to consider economic, social, and environmental responsibility, the question is no longer whether to implement sustainability strategies, but how [

15]. Many authors argue that the focus of future research should shift from the question of whether companies should implement sustainability strategies to how they should do so in practice. They call for empirical studies on the implementation of sustainability in the corporate environment [

12,

14,

16,

17].

Successfully embedding sustainability into corporate operations requires identifying the critical success factors that determine whether a strategy is effectively executed. The notion that certain elements are critical to organisational success has long been recognised. Rockart [

26], who expanded on the work of Daniels [

27], introduced the concept of critical success factors (CSFs)—key tasks that must be performed exceptionally well for a company to be successful. The CSFs for any company are a limited number of areas, the results of which, if satisfactory, ensure the achievement of a competitive advantage for the company and thus support the achievement of organisational goals [

26].

Based on the definition of critical success factors, when applied in the context of sustainability strategy implementation, critical success factors for implementing corporate sustainability strategies are those factors that positively or negatively affect the success of sustainability strategy implementation [

12]. Therefore, companies must identify and manage these key success factors to ensure the successful implementation of sustainability strategies and achieve the goals outlined in the strategies.

3. Methods

The systematic literature review (SLR) methodology was chosen for this study because it provides a structured, transparent, and replicable approach to synthesising existing research while minimising bias. The SLR was conducted according to the step-by-step systematic review process presented by Thomé for operations management [

28]. While systematic reviews are well established in fields such as psychology and medicine, management science has historically lacked similar rigour. Thomé et al. address this gap with a step-by-step methodology that ensures transparency and replicability through systematic inclusion criteria, backward and forward searches, coding reliability checks, and quality assessments. Although originally developed for operations management, their approach is equally applicable to strategic management, making it a robust choice for this study.

The purpose of this research was to answer the research questions RQ1–RQ3, as listed in the

Section 1.

The selected databases were Scopus and ScienceDirect, both last accessed on 19 November 2024. A set of keywords was applied to databases, including corporate sustainability strategy, implementation, and critical success factors or success factors. The selection of keywords was informed by an initial, unsystematic review of the literature, through which we identified seminal sources and recurring terminology in the field. Multiple keyword sets were tested iteratively, and the final combination was selected based on its ability to yield results most aligned with the focus of this study. Recognising the inherent limitations associated with inconsistent keyword usage across publications, we complemented the database search with an extensive backward and forward snowballing procedure to enhance the comprehensiveness and robustness of the review. Three reviewers independently screened all records and extracted data, resolving any discrepancies by consensus. No automation tools were used in either stage. This review was conducted in accordance with PRISMA guidelines (see

Supplementary Materials to consult the PRISMA checklist); the review was not registered.

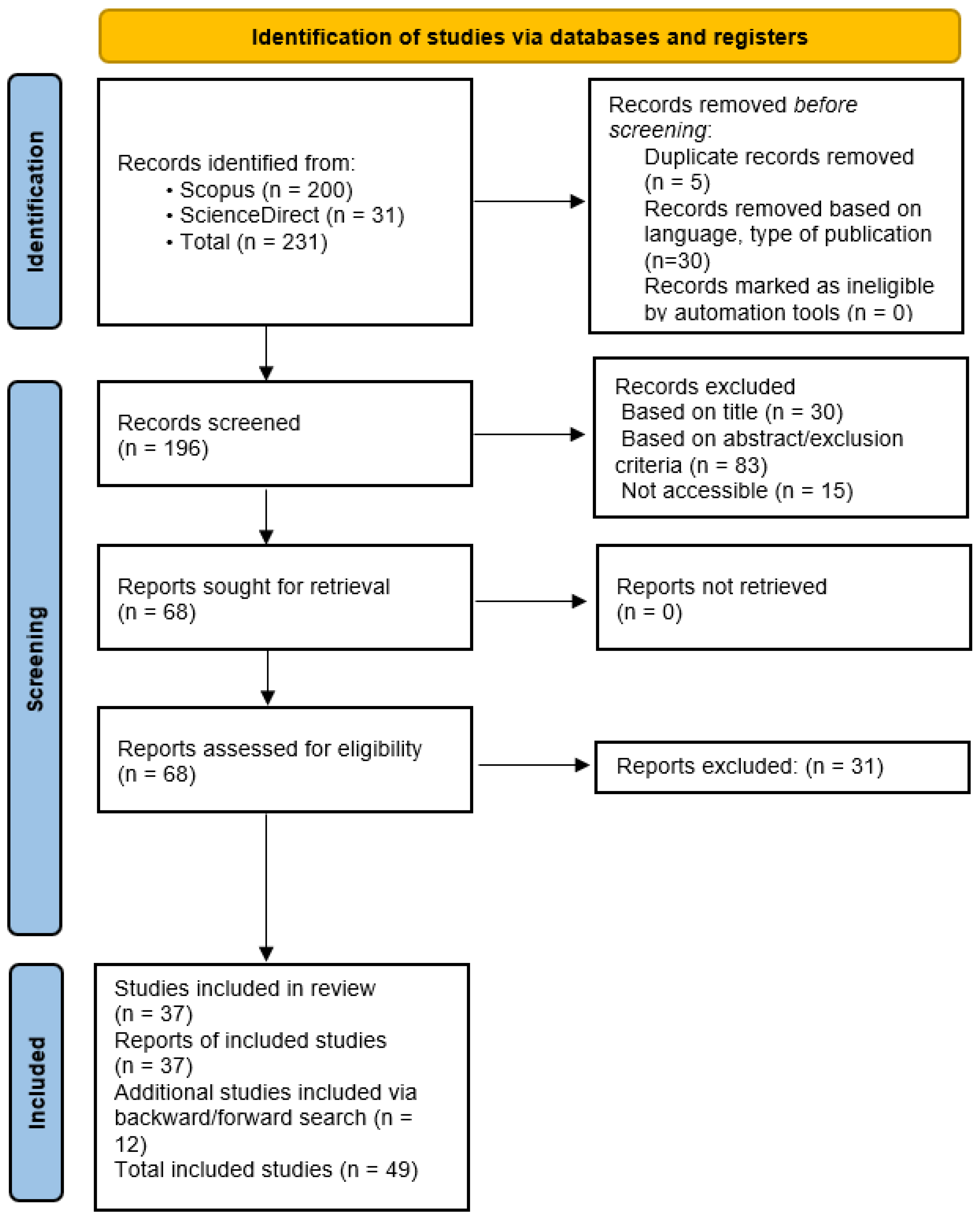

No time constraints were specified for publications. The SLR process is presented with the PRISMA flow diagram in

Figure 1. Initial research returned a total of

231 publications. In the next step, we applied inclusion and exclusion criteria, as shown in

Table 1. The inclusion and exclusion criteria ensured the selection of the relevant literature for the systematic literature review. Only peer-reviewed journal articles, conference papers, and books published in English were included. This review focused on studies that examined the implementation of sustainability strategies in production companies, excluding research on sustainability at the societal level, service sectors, agriculture, health care, and the like. The inclusion criteria covered terms such as sustainability, corporate sustainability, social responsibility, and ESG, which are not strict synonyms but are often used interchangeably to describe similar concepts. Although this study is explicitly focused on corporate sustainability, related terms such as corporate social responsibility and ESG were included due to their frequent use as conceptual equivalents in the literature. As previously clarified, these terms share overlapping characteristics but differ in emphasis and scope. Terms with a more limited or distinct focus—such as circular economy, which primarily addresses environmental aspects—were excluded to maintain alignment with the strategic and integrative perspective of corporate sustainability. Studies that addressed general or partial implementation of sustainability strategies, such as supply chain practices or environmental policies, were included, while those that focused solely on circular economy implementation were excluded. After applying inclusion and exclusion criteria,

201 publications remained, of which

5 were duplicates. A review of the abstracts identified

83 publications, and a review of the full texts identified

37 publications for content review. Backward and forward searches identified

12 additional publications, bringing the total number of included publications to

49. The large number of articles identified through backward and forward searches resulted from the variation in keyword usage across studies, as similar topics were often described using different terms. This made it challenging to define a precise keyword set, necessitating a broader search strategy to ensure the inclusion of the relevant literature.

Content analysis provides a synthesis of knowledge in the field of research under investigation, employing the literature review approach, which is characterised as a qualitative synthesis of findings [

28]. To systematically classify the results of the content analysis, the taxonomy approach was chosen, using the iterative taxonomy development method of Nickerson et al. [

29]. Nickerson provides a structured step-by-step process for developing a taxonomy to group objects of interest into a domain based on common characteristics, along with a set of stopping conditions to validate the results obtained [

29].

First, the purpose of the taxonomy was established, aimed at identifying CSFs for the implementation of corporate sustainability strategies in production companies. Subsequently, the meta-characteristic of the taxonomy was defined as the internal success factors that influence the implementation of corporate sustainability strategies. This meta-characteristic highlights the internal organisational elements that affect how sustainability is integrated and managed within a company.

As an iterative method, the conditions that terminate the process were determined according to Nickerson [

29], with the set of final conditions comprising two approaches: objective and subjective. For the final conditions, the taxonomy must adhere to the established definition, requiring it to consist of dimensions with mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive characteristics. The objective ending conditions require that no object is merged with a similar one or split into multiple objects during the last iteration, no new dimensions or characteristics are introduced, and no dimensions or characteristics are merged or split in the final iteration. The subjective ending conditions emphasise conciseness, ensuring that the number of dimensions is meaningful without being overwhelming, with a suggested range of seven plus or minus two [

30]. Robustness is necessary to provide sufficient differentiation among objects, while extendibility ensures that new dimensions or characteristics can be easily added when needed. It took 4 iterations of the method to obtain the taxonomy. After each iteration, the taxonomy was refined until all ending conditions were met, ensuring that the final version was both robust and extendable.

To ensure the reliability and validity of the taxonomy, two authors independently coded the initial pool of identified CSFs using a shared, iteratively refined coding protocol. After the first round, the level of overlap between the two code sets was high; remaining discrepancies were resolved through two reconciliation workshops until full consensus was achieved. To guard against individual bias, the near-final taxonomy was then reviewed by an external panel comprising three sustainability scholars and two senior manufacturing managers. Their feedback resulted in minor wording adjustments, while the category structure remained unchanged.

The empirical-to-conceptual approach was chosen for the taxonomy. First, objects to be classified were identified, followed by the identification of common characteristics based on the meta-characteristics. Finally, these characteristics were used to define dimensions for classification.

4. Identification of Critical Success Factors for Implementing Corporate Sustainability Strategies

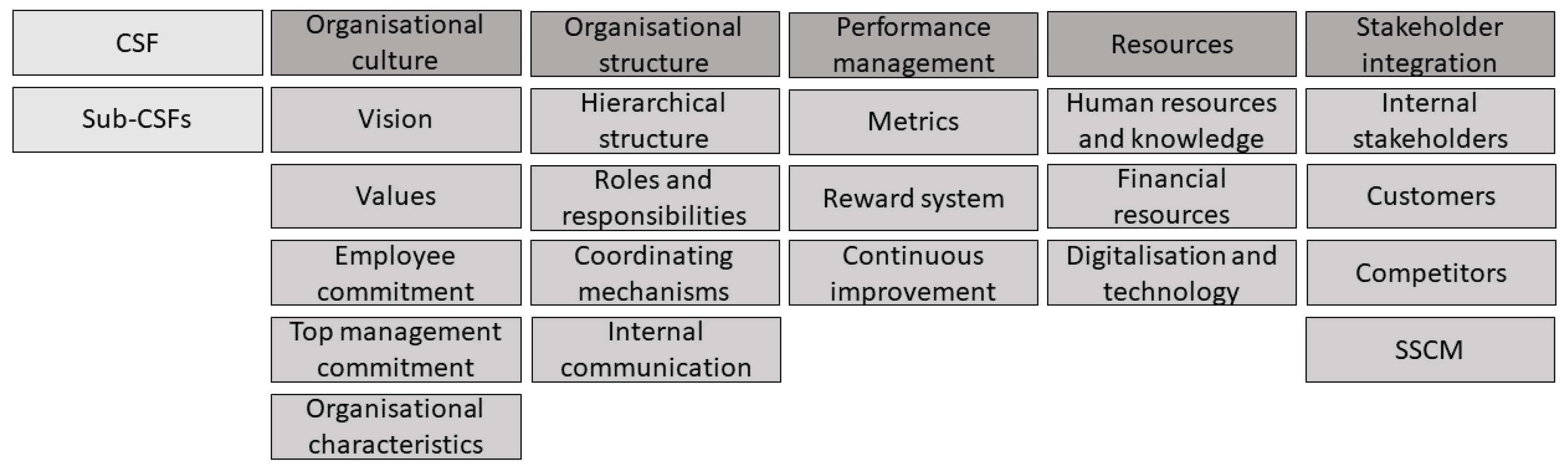

In our research, we identified 243 CSFs that influence the implementation of corporate sustainability strategies in production companies, with some factors recurring across multiple publications. These CSFs were categorised into five main groups: organisational culture, organisational structure, performance management, resources, and stakeholder integration. Each main group was divided into subcategories to provide a clear and structured understanding of the factors.

4.1. Taxonomy of Critical Success Factors

The developed taxonomy provides a structured overview of the CSFs, each grouped into relevant categories to highlight their role in implementing corporate sustainability strategies.

Figure 2 shows the taxonomy and the identified CSFs. The top row lists the main CSFs, which include organisational culture, organisational structure, performance management, resources, and stakeholder integration. Below each CSF, the corresponding sub-CSFs are presented, representing key elements that contribute to the successful implementation of sustainability strategies. The first group,

organisational culture, emphasises key aspects such as vision, values, employee commitment, top management commitment, and organisational characteristics like collaboration, innovation, and learning orientation. The second group,

organisational structure, focuses on hierarchical structures, roles and responsibilities, coordinating mechanisms, and internal communication.

Performance management, the third group, includes metrics, reward systems, and continuous improvement processes. The fourth group,

resources, highlights the importance of human resources and knowledge, financial resources, and digitalisation and technology. Lastly,

stakeholder integration encompasses the importance of relationships with internal stakeholders, customers, competitors, and the implementation of sustainable supply chain practices.

Each critical success factor and subcategory is supported by references from the literature, which are listed in

Table 2. These references provide the theoretical foundation and practical insights that validate the inclusion of each factor in the taxonomy. This approach ensures that the taxonomy is both comprehensive and grounded in existing research.

The role and importance of identified CSFs in implementing corporate sustainability strategies is explored in greater detail in

Section 4.2.

4.2. Role of Critical Success Factors

Section 4.2 provides a more detailed explanation of how the identified CSFs support the implementation of corporate sustainability strategies.

4.2.1. Organisational Culture

Organisational culture can act as both a barrier and enabler for sustainability [

31]. Effectively integrating sustainability into strategic management requires embedding it into the organisational culture [

12,

43,

44], shaping how organisations think, act, and address sustainability challenges [

32].

Organisational culture is defined by Schein as

a pattern of basic assumptions that members of an organisation have learned in the process of solving problems of external adaptation and internal integration, which have worked well enough to be considered valid and consequently to be taught to new members as the correct way to perceive, think, and feel in relation to those problems [

76], or as

a set of basic assumptions which members of an organisation have in their mind and which influence them in thinking and acting [

77]. Sustainability-oriented culture extends these definitions to include shared values and beliefs focused on sustainability and balancing economic, social, and environmental outcomes [

33,

34,

35]. It provides the justification for people’s actions and helps employees to determine desirable behaviors (concerning sustainability) in the absence of close monitoring and control by managers [

36]. A sustainability-oriented culture ensures that sustainability becomes a core part of decision-making, is seamlessly integrated into operations [

5], and strengthens employee commitment to sustainability goals [

44].

Kantabutra and Avery propose a self-reinforcing sustainability model based on vision, values, and individuals who embody them [

38]. A clear

sustainability vision acts as a declaration of leadership’s commitment to sustainability, guiding employees to focus on priorities that matter most to the organisation and its stakeholders [

33,

39].

Sustainability values, such as social responsibility and innovation, shape behaviour and foster a strong culture through leadership commitment and alignment with personal values [

34,

78]. Effectively communicating vision and values ensures that employees align their actions with organisational goals, fostering commitment to sustainability [

39,

40]. This commitment motivates employees to take ownership of sustainability initiatives and integrate them into their daily work [

39].

Top management commitment is critical, driving sustainability integration into decision-making and activities across business units. Without this leadership, key functions like procurement and supply chain management may lack engagement in sustainability initiatives [

41]. Top management commitment has a significant influence on strategic decisions and fosters a genuine commitment to sustainability [

14,

43,

44,

45,

79]. This commitment extends to middle management and employees, who often reflect the leadership’s values and practices [

33]. Motivated employees who view sustainability as integral to their work contribute to achieving TBL outcomes, meaning economic, social, and environmental performance, thus enhancing stakeholder satisfaction and brand equity [

5,

39]. This motivation can be strengthened by enhancing employee qualifications, increasing their understanding of the importance of sustainability, or by recognising their contributions through appropriate reward systems [

14]. TBL achievements further reinforce shared sustainability assumptions, transforming them into ingrained beliefs and strengthening the culture [

33,

42,

76].

Collaboration, innovation, and

learning orientation in an organisation are vital for sustainability. Collaborative cultures foster teamwork, decentralised decision-making, and open communication, enabling knowledge sharing and solution development [

33,

35]. Innovation promotes adaptive approaches [

37], while learning-oriented cultures drive continuous improvement [

12]. Individuals play a crucial role in this process, as change agents help shape sustainability culture by influencing behaviour, facilitating integration mechanisms, and adapting sustainability principles to the organisational context [

46].

4.2.2. Organisational Structure

Organisational structure is important for corporate sustainability, as it shapes how tasks, responsibilities, and coordinating mechanisms are designed to achieve sustainability objectives. Drawing on Mintzberg’s definition, the organisational structure is

the sum total of the ways in which its labour is divided into distinct tasks and then coordinated [

80]. Beyond ensuring coherence and efficiency, it must also adapt to meet the interdisciplinary demands of sustainability, by integrating environmental, social, and economic goals [

12,

81].

Embedding sustainability into strategic management requires aligning

hierarchical structures with sustainability objectives [

14,

81]. Traditional hierarchies often need adaptation, with clearly defined

roles and responsibilities to avoid inefficiencies, especially in subsidiaries or joint ventures [

47,

48]. Many organisations address this by establishing dedicated sustainability departments, steering committees, or cross-functional teams to ensure accountability and align resources with corporate sustainability goals [

14,

48,

53].

Collaboration across functions and departments is vital for embedding sustainability into strategic management, as well as addressing the interdisciplinary challenges that require input from diverse domains [

12,

14,

45].

Coordinating mechanisms, such as sustainability councils or cross-functional Kaizen teams, play a pivotal role in linking sustainability efforts with organisational accountability. Establishing a sustainability council and remuneration committee ensures that top management performance is tied to sustainability outcomes, which promotes better monitoring and accountability [

48,

49]. Regular cross-departmental meetings and feedback loops ensure that sustainability becomes a shared responsibility across all departments, including traditionally less involved ones, strengthening alignment and integration [

5,

14,

17,

48,

50].

Effective

internal communication, as mentioned in organisational culture, is essential for implementing sustainability strategies, bridging the gap between stated corporate values and practices [

12,

14,

48] and fostering employee commitment [

44]. Robust mechanisms reinforce sustainability objectives at all levels, with top management playing a key role by actively engaging employees through emails, intranet updates, and meetings to align vision, values, and trust [

5,

33]. Transparent messaging helps employees understand sustainability goals and integrate them into their daily operations, creating a shared sense of purpose [

12,

51,

52]. Cross-departmental communication is equally critical, facilitating collaboration and coherence in strategies through regular interactions and meetings [

14]. Effective cross-functional communication not only improves collaboration but also strengthens the organisation’s ability to implement sustainability initiatives consistently [

41].

4.2.3. Performance Management

Performance management is important for corporate sustainability, as it ensures that sustainability objectives are integrated into decision-making and operations. It also enables organisations to align their strategies with sustainability goals by providing tools and frameworks for monitoring, evaluating, and improving performance [

43,

54,

55]. Among these tools, the Sustainability Balanced Scorecard (SBSC) serves as a structured framework that integrates sustainability into strategic management by embedding economic, social, and environmental objectives into performance measurement, supporting decision-making and aligning corporate sustainability efforts with broader strategic goals [

57,

58,

59,

60].

Metrics are fundamental to effective corporate sustainability performance management, providing tools to monitor, evaluate, and manage progress towards sustainability objectives, ensuring transparency and informed decision-making [

55].

Organisations often face challenges in assessing performance before and after implementing strategies, particularly in selecting and adapting indicators to align with management tools [

12,

14,

45,

48,

56]. Setting measurable performance indicators at organisational, business unit, and individual levels ensures a clear link between sustainability targets and concrete actions. Including sustainability in key performance indicators (KPIs) focuses attention on critical issues and makes goals more tangible [

5,

14]. Setting measurable, role-specific targets enables all employees to contribute effectively to the company’s sustainability goals [

5].

Assessing a company’s sustainability performance requires a combination of qualitative and quantitative metrics, as each provides complementary insights. Qualitative metrics identify areas for improvement, while quantitative metrics track progress, delivering reliable results. This dual approach, as recommended by the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), ensures a comprehensive understanding of sustainability performance [

54].

Metrics aligned with the TBL are essential for a holistic evaluation. By encompassing social, environmental, and economic dimensions, TBL metrics ensure that organisations address all facets of sustainability in their strategies and operations [

32,

39]. Integrating non-financial metrics, such as social equity and environmental impact, into performance assessments ensures that progress is aligned with objectives [

12]. The regular monitoring and analysis of the TBL dimensions enable companies to identify gaps, make timely adjustments, and ensure continuous alignment with their sustainability goals [

32].

While TBL metrics provide a comprehensive framework for assessing sustainability performance, organisations also require structured systems to integrate these metrics into their daily operations and decision-making. The adoption of management systems plays a critical role in promoting sustainability by ensuring that organisations have an established system for managing impacts and tracking progress [

44]. Integrated management systems (IMSs) combine frameworks like ISO 14001 (Environmental Management System), EMAS (Eco-management and Audit Scheme), ISO 9001 (Quality Management System), and SA8000 (Standard for Social Accountability) to enhance sustainability performance. These systems ensure transparency, accountability, and operational efficiency, providing a robust foundation for sustainable operations and organisational change [

12,

14,

55].

Reward systems are pivotal in aligning employee performance with sustainability objectives [

14,

45,

49]. Organisations achieve this by integrating sustainability-focused key performance indicators (KPIs) into performance reviews and reward structures, providing role-specific clarity and measurable expectations [

5,

48]. This alignment ensures that individual contributions are directly linked to broader corporate sustainability goals [

14].

Continuous improvement is an essential component of performance management, requiring the ongoing evaluation of both old and new measures to drive progress [

45,

54]. Continuous improvement regarding sustainability is defined as fostering a culture of enhancing the three dimensions of sustainability across products, processes, systems, and supply chains by engaging supply chain partners and stakeholders [

49].

4.2.4. Resources

The availability of financial resources,

human resources and knowledge [

61], and technological resources [

62] is a critical success factor for the implementation of corporate sustainability strategies [

5,

14,

43,

44,

48,

49].

According to the Knowledge-Based Theory, knowledge is the most important strategic resource [

82] and can provide a sustainable competitive advantage when effectively managed [

39]. Integrating sustainability into strategic management requires creating, sharing, and developing knowledge within and across organisational boundaries [

39,

45,

54]. Internal training programmes and periodic refresher courses enhance employees’ understanding of sustainability’s environmental, social, and operational impacts, helping align daily tasks with broader goals [

5,

14,

48,

49].

Management skills and strategic recruitment practices are essential to achieving sustainability objectives. The ability of top management to adopt cleaner practices and implement sustainable technologies is pivotal [

37,

63]. Targeted awareness and training programmes, organised by governments and policymakers, play a key role in enhancing their skills, particularly in planning and managing sustainability projects [

49]. Sustainable organisations focus on hiring talent that aligns with their vision and core values, ensuring that new recruits contribute to their long-term goals [

33,

39,

62]. To build resilience and uphold their principles, sustainable companies avoid layoffs and focus on retaining high-performing successors, who share the organisation’s vision [

33].

Adequate

financial resources are essential for embedding sustainability into strategic management, as this requires significant investment in new technologies, certifications, and human resources. This is particularly true in the early stages [

12], which can be a barrier as the financial benefits are often unclear [

45]. Although these investments can seem substantial, they yield long-term benefits, such as financial savings, cost avoidance, and improved economic performance [

12,

49]. Larger organisations often possess a greater financial capacity for the implementation of sustainability initiatives [

61,

64], while SMEs face constraints and may prioritise short-term gains over long-term sustainability. Government support, including subsidies, tax breaks and financing programmes, is crucial for assisting SMEs and fostering green supply chains, technological upgrades, and sustainable growth, particularly in developing regions [

37,

44,

49].

Digitalisation and technological advancements are critical drivers of sustainable development, enabling organisations to adapt to their rapidly changing technological environments [

68]. Digitalisation, defined as

the transformation of business models and processes through information and communication technology (ICT) [

54], accelerates the transition to environmentally sustainable practices and improves competitiveness [

37,

49,

54]. Industry 4.0 is a key enabler of this transformation, driving automation, efficiency, and real-time decision-making [

65]. Blockchain, the Internet of Things (IoT), and cyber–physical systems (CPSs) play a crucial role in transforming supply chains into more sustainable, transparent, and efficient systems [

67].

Key Industry 4.0 technologies, such as the IoT, CPSs, and sensors, play a significant role in enhancing resource efficiency by enabling real-time data collection and feedback, thereby improving operational sustainability [

65]. Additive manufacturing reduces waste and supports circular economy practices [

65], while blockchain enhances supply chain transparency by addressing issues such as fraud, pollution, and human rights violations [

66]. Big data and robotics further support sustainability through advanced analytics and automation, though their impact on job creation highlights challenges from the TBL perspective. Cloud computing and system integration technologies also support sustainable development, but their impact is greater in industries that are already advanced in automation and digitisation [

65].

Industry-specific technologies and effective data management systems are essential for advancing sustainability initiatives. Within the Industry 4.0. framework, tailored technologies in areas such as sustainable manufacturing, waste management, and resource recycling address the unique needs of different industries, ensuring that sustainability practices align with sector-specific challenges [

49,

65].

Information systems play a pivotal role in an organisation’s transition to sustainability by providing updated data, enabling timely decision-making, and reducing uncertainties and risks in supply chain sustainability initiatives. The use of information and communication technologies is essential for collecting, integrating, automating, and monitoring sustainability-related data, such as greenhouse gas emissions, energy consumption, and waste streams [

49]. These systems enable organisations to assess performance, implement improvements, and align their operations with overarching sustainability objectives [

54].

4.2.5. Stakeholder Integration

Integrating stakeholders into corporate sustainability strategies is essential in a competitive business environment, where stakeholders expect companies to adopt sustainable practices and maintain socially responsible supply chains [

55]. Stakeholder theory emphasises the ethical responsibility to consider the needs of stakeholders, such as employees, customers, and communities, when making decisions, fostering long-term relationships, and improving corporate sustainability [

83]. Prioritising stakeholder relationships and meeting their expectations is a fundamental part of driving sustainable initiatives [

37]. Building strong relationships with stakeholders requires mapping their needs, maintaining continuous communication, and incorporating reciprocal feedback from sources such as market research and employee input [

69].

Internal stakeholders, including employees, investors, and management, drive sustainability through leadership and collaboration, while external stakeholders, such as customers, suppliers, NGOs, governments, and communities, influence corporate practices and monitor compliance [

44,

70].

Customers play a pivotal role in market-driven companies [

45] as their buying decisions determine revenue [

44,

71]. Growing consumer awareness of social and environmental issues, amplified by social media, has pressured companies to adopt sustainable policies. Educating consumers about the environmental impact of products boosts demand for sustainable solutions, fostering innovation and customer-driven sustainability [

37,

49,

70]. However, over-prioritising customer needs can create long-term risks by neglecting other stakeholders. Companies must balance customer demands with broader sustainability objectives [

69].

Competitors can have a positive effect on the implementation of sustainability when their actions influence corporate management, customers, or suppliers to adopt sustainable practices [

44,

45,

71]. Coopetition, a blend of competition and cooperation, enables competitors to collaborate for shared benefits, such as expanding market opportunities, reducing risks, and fostering innovation [

39,

52]. Through their sustainability initiatives, competitors can set benchmarks that encourage others in the industry to adopt higher standards, driving collective progress [

71]. External relationships, such as alliances, networks, and ecosystems, provide access to essential resources and capabilities while fostering interactions that generate social, environmental, and economic value [

37,

44,

72]. Ecosystems, in particular, allow competitors to align on shared goals and develop interdependencies that enhance value creation without the need for direct collaboration. This alignment supports industry-wide improvements and the collective advancement of sustainable practices [

72].

Suppliers play a pivotal role as stakeholders [

45] in achieving sustainability through

sustainable supply chain management (SSCM). SSCM involves managing materials, information, and capital flows while aligning with the economic, environmental, and social dimensions of sustainable development, as derived from stakeholder requirements [

73]. The purchasing department is central to SSCM, interacting with suppliers, contractors, and other stakeholders to integrate sustainability objectives throughout the supply chain [

71]. Collaboration is crucial to be able to overcome challenges such as globalisation and outsourcing, which complicate sustainability efforts [

62]. Building trusting, long-term relationships with suppliers promotes effective communication, collaborative problem-solving, and the successful implementation of sustainability programmes. Aligning goals and establishing mutual understanding between supply chain partners improves both sustainability performance and competitiveness [

49].

Effective supplier sustainability management combines compliance and development strategies [

74] to evolve the traditional buyer–supplier dynamic into a collaborative partnership [

41]. Compliance strategies include tools such as codes of conduct, audits, and monitoring mechanisms that align supplier behaviour with organisational expectations. Codes of conduct establish shared values and ethical standards, while audits and monitoring verify compliance with those standards [

41,

74]. Tools such as TBL audits evaluate the economic, environmental, and social dimensions, fostering accountability even in regions with weak enforcement mechanisms. Compliance strategies are more effective when paired with supplier audits and risk assessments, ensuring comprehensive evaluations of supplier performance [

41]. Supplier development strategies (SDSs) focus on strengthening supplier capabilities through direct approaches like training, education, and technical or financial support. These strategies also include indirect methods, such as supplier evaluations and informal audits, which encourage suppliers to address challenges independently. Collaboration is a cornerstone of SDSs, fostering trust, joint problem-solving, and long-term relationships. Beyond individual capabilities, SDSs often target logistics, resource allocation, and energy efficiency, yielding positive impacts on external activities like transportation and internal operations, such as material management [

74]. The results indicate that compliance strategies have a wide, positive impact on all supplier environmental activities, while environmental supplier development, in the form of direct projects, only affects supplier environmental activities in logistics and transport [

75]. By combining compliance and development strategies, organisations build a resilient supplier base that aligns with sustainability objectives while improving overall supply chain efficiency and long-term competitiveness [

74].

5. Interrelationships Between Critical Success Factors

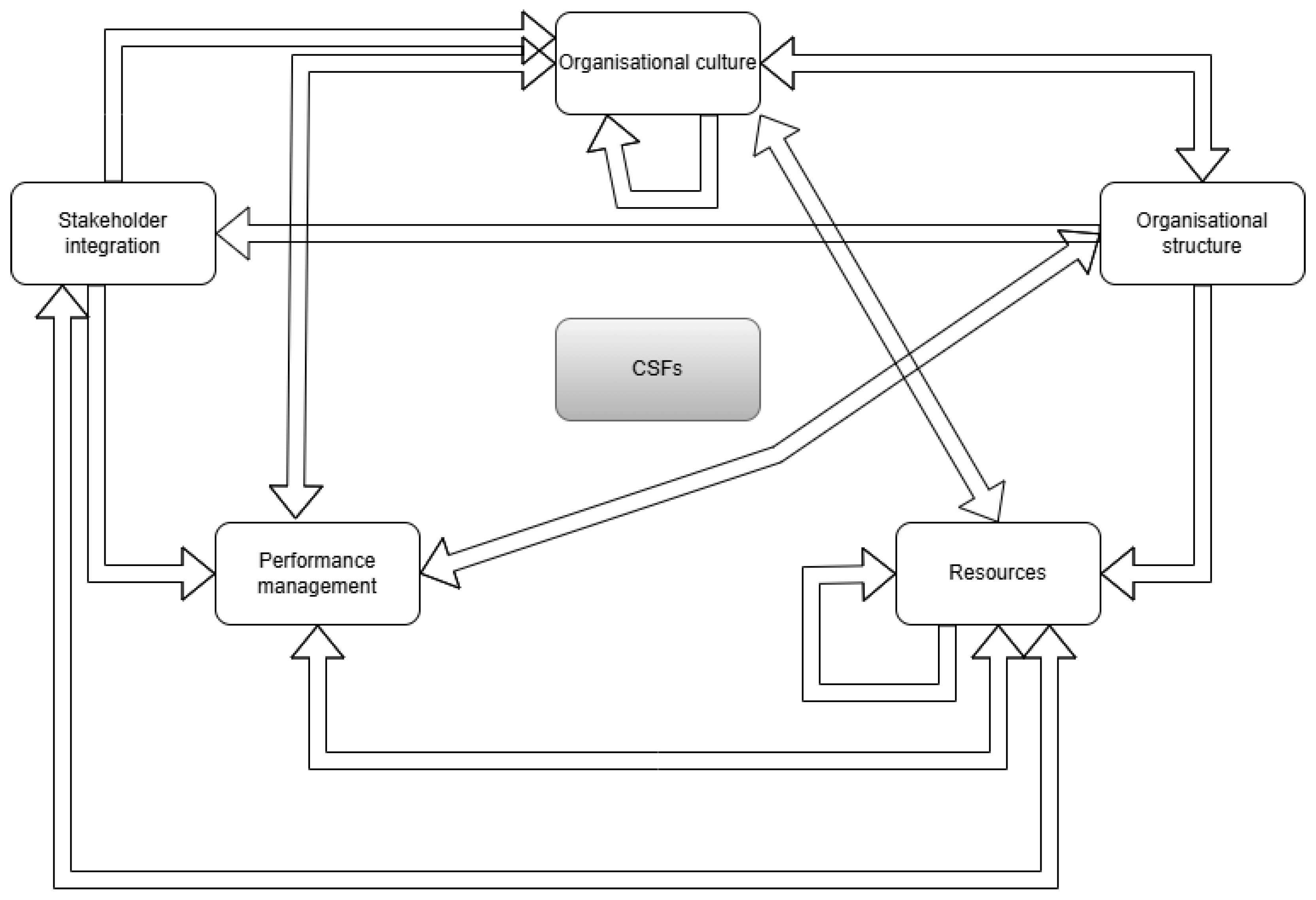

The implementation of corporate sustainability strategies relies on the interrelations between CSFs. These factors form a dynamic, interdependent system, where no single CSF can function effectively in isolation. Based on the findings from the literature review, we identify and present these interrelationships in the

Figure 3, where arrows indicate the direction of influence. A CSF at the start of an arrow impacts the CSF at the arrow’s endpoint. Bidirectional arrows indicate mutual influence, highlighting feedback loops. This visualisation provides a structural view of how CSFs interact in sustainability strategy implementation. In the following discussion, we further examine these interrelationships and their implications.

Top management commitment acts as a central driver, influencing several CSFs. It shapes organisational culture by embedding sustainability values into daily operations, motivating employees, and fostering long-term engagement [

5,

61], and it is crucial in driving the change process. It influences organisational structure, ensuring effective communication channels and institutionalising sustainability in the form of sustainability departments, councils, and overall architecture [

37,

43]. Top management shapes the performance management system and the reward system, drawing employees’ attention to the sustainability issues over the long term and increasing their motivation and commitment, which in turn strengthens organisational culture [

5,

43,

48,

61]. Top management commitment is further crucial for resource allocation, as leadership drives investments in financial, human, and technological resources required to overcome barriers, such as knowledge gaps and cost constraints. By prioritising sustainability initiatives, top management ensures that adequate resources are available to adopt tools, build capabilities, and support long-term sustainability goals [

12,

43,

55]. Management’s strategic decision to hire new employees, who uphold the same values as the organisation, further strengthens the organisational culture [

39].

Organisational structure plays a key role in aligning CSFs such as performance management, organisational culture, resources, and stakeholder integration to support corporate sustainability. Organisational structure enables performance management by creating sustainability-focused units such as sustainability departments, councils, and committees. These ensure clear responsibilities, integrate sustainability into performance systems, and align individual efforts with measurable goals [

53]. The establishment of sustainability councils and remuneration committees further supports this by linking the performance of the top management to sustainability outcomes, ensuring accountability and monitoring [

48]. It strengthens organisational culture through internal communication channels—such as shared events and symbols—that embed sustainability values across departments [

39]. This alignment also raises awareness and connects the organisation with stakeholders, promoting shared environmental and social goals [

41]. Additionally, regularly scheduled cross-functional meetings integrate sustainability into performance and initiatives, emphasising that sustainability “should be part of everyone’s job” and promoting collaboration across departments, industries, and suppliers [

17]. For resource allocation, a clear structure ensures leadership prioritises financial, human, and technological resources to overcome challenges like cost and knowledge gaps. Coordination between management and employees ensures these resources align with sustainability priorities [

5].

At the same time,

performance management influences organisational structure by providing integrated sustainability data that aligns with complex global operations. This integration connects distributed personnel and expertise to actionable insights, enabling structural adjustments that better support sustainability goals. Quantifying the link between sustainability actions, performance, and financial outcomes strengthens the business case for sustainability, encouraging organisations to adapt their structures for greater efficiency and alignment with sustainability priorities [

17]. Performance management also impacts motivation through reward systems. Reward systems tied to sustainability outcomes provide incentives for employees to align their efforts with organisational goals. While some managers argue that reward systems drive only short-term motivation, others emphasise that recognition and appreciation foster long-term commitment to sustainability values and goals [

14].

Resources are a foundation for enabling and strengthening other CSFs, essential for implementing corporate sustainability strategies. Financial resources support technology adoption by overcoming barriers like high costs, skills shortages, and organisational limitations [

67]. Investments in digital tools enable accurate data collection, integration, and the real-time monitoring of sustainability metrics, such as energy use and emissions. This enhances performance management by improving monitoring, accountability, and operational efficiency, enabling informed decision-making and progress tracking [

49,

54]. Within Industry 4.0, these digital advancements further transform supply chains into more sustainable, transparent, and efficient ecosystems by leveraging the IoT, blockchain, and AI to optimise resource use, enhance traceability, and improve decision-making [

67]. At the same time, digital ecosystems are reshaping stakeholder integration by enabling collaboration between companies, suppliers, and institutions through interconnected platforms and data-sharing technologies. These ecosystems facilitate multi-stakeholder engagement and improve coordination in sustainable production and decision-making processes [

72]. Knowledge resources improve motivation and change management. Training equips employees to understand the impact of sustainability on their tasks, boosting their commitment and aligning their efforts with organisational goals [

12,

14]. Organisational learning fosters innovation, flexibility, and the skills needed to manage transitions toward sustainability [

12,

32]. Human resources shape organisational culture by aligning recruitment and retention with sustainability values. Prioritising talent that shares the company’s vision and avoiding layoffs during challenges builds a resilient culture and ensures long-term alignment with sustainability goals [

33].

Stakeholder integration enhances performance management by providing insights for developing sustainability metrics, such as TBL indicators. Feedback from customers, suppliers, and third-party rankings ensures performance systems align sustainability goals with operations and strategy [

17]. It also reinforces organisational culture by raising awareness and influencing external stakeholders. For example, educating consumers about the environmental impact of products increases demand for sustainable solutions, motivating companies to innovate and adopt sustainable practices [

44,

49]. In terms of resources, stakeholder relationships provide access to external capabilities, particularly for firms with limited internal resources. Strong supplier networks and collaborations drive innovation, support sustainable technologies, and address resource constraints. In addition, these relationships promote knowledge sharing, enabling the exchange of ideas and skills both internally and externally. This collaboration encourages organisational learning and innovation, supported by a clear sustainability vision that promotes new ideas and continuous improvement [

37,

39,

72].

6. Discussion

Despite the proliferation of sustainability frameworks and increased awareness, the gap between strategic intent and effective implementation persists. This is often due to conflicting short-term financial priorities, insufficient sustainability competencies at the middle management level, and organisational inertia that hinders the translation of goals into action. The successful implementation of corporate sustainability strategies relies on the interconnectedness of CSFs that form a dynamic and interdependent system.

In response to

RQ1, this study identifies five CSFs that influence the implementation of corporate sustainability strategies:

organisational culture, organisational structure, performance management, resources, and stakeholder integration. These factors were derived from a systematic literature review, which identified a total of 243 individual CSFs. To ensure a structured and comprehensive classification, we followed the taxonomy development approach according to Nickerson [

29], and categorised the identified CSFs into five groups. The classification is both exhaustive and exclusive, covering all relevant aspects of sustainability strategy implementation while allowing for the easy integration of additional factors as these are identified. Compared with earlier CSF overviews that focus on isolated factors, our taxonomy visualises the systemic interplay among five success dimensions (

Figure 3) and, for example, singles out ‘digitalisation and technology’ within the resource base—a factor increasingly decisive in production environments yet overlooked in prior syntheses.

Each of the five CSFs consist of sub-CSFs to provide a more detailed understanding. Organisational culture includes vision, values, employee commitment, top management commitment, and organisational characteristics such as collaboration, innovation, and learning orientation. Organisational structure encompasses hierarchical structure, roles and responsibilities, coordinating mechanisms, and internal communication. Performance management includes metrics, reward systems, and continuous improvement processes. Resources refer to human resources and knowledge, financial resources, and digitalisation and technology. Finally, stakeholder integration includes relationships with internal stakeholders, customers, competitors, and suppliers.

In response to RQ2, we examine the role of the identified CSFs in the successful implementation of corporate sustainability strategies.

Organisational culture ensures that sustainability becomes a core part of corporate decision-making by embedding shared values, vision, and leadership commitment. A strong sustainability-oriented culture fosters employee engagement, collaboration, and innovation. Leadership plays a crucial role in shaping this culture by setting clear sustainability priorities, demonstrating commitment through actions, and influencing employees to integrate sustainability into their daily work.

Organisational structure facilitates sustainability by establishing clear responsibilities, accountability mechanisms, and cross-functional collaboration. Dedicated sustainability departments, steering committees, and interdisciplinary teams help align sustainability objectives with corporate strategies. Effective coordinating mechanisms, such as sustainability councils and cross-departmental meetings, ensure that sustainability is embedded in all business functions. Internal communication is key to ensuring effective information flow between departments and translating sustainability goals into action.

Performance management ensures transparency and accountability in sustainability strategy implementation. Performance metrics should be TBL-oriented and measurable and include both quantitative and qualitative aspects at the organisational, business unit, and individual levels. A TBL approach ensures consideration of economic, social, and environmental dimensions, with qualitative measures identifying areas for improvement and quantitative measures tracking progress. Setting metrics at all levels directly links sustainability objectives to operations and decision-making. Integrating sustainability into performance evaluations and reward systems further reinforces its importance, aligning employee contributions with long-term sustainability goals.

Resources—including human resources and knowledge, financial resources, and digitalisation and technology—play a critical role in the implementation of sustainability. Employees must be equipped with the necessary skills to effectively integrate sustainability into operations. While implementation requires significant upfront investments in infrastructure, compliance, and process improvements, these expenditures lead to long-term financial benefits such as cost savings and operational efficiency. Digitalisation and technology further enhance sustainability by enabling real-time performance tracking, resource optimisation, and greater supply chain transparency.

Stakeholder integration plays a key role in aligning corporate sustainability efforts with external expectations and requirements. Customers drive demand for sustainable products, while competitors influence the industry-wide adoption of sustainability practices. Companies ensure sustainability in their upstream supply chains through compliance strategies, such as codes of conduct, audits, and monitoring, and supplier development strategies, including training, education, and financial or technical support. External partnerships, including business networks and alliances, facilitate resource sharing and promote sustainability innovation.

A key contribution of this study is the comprehensive answer to RQ3, which shows that each CSF plays a distinct and essential role while simultaneously reinforcing the others. No factor works alone; they interact and support each other to achieve long-term sustainability goals.

Top management commitment is the central driver of sustainability. It shapes organisational culture by embedding sustainability values into daily operations and fostering long-term employee commitment. It influences organisational structure by institutionalising sustainability through dedicated units and governance mechanisms. It also impacts performance management by embedding sustainability into evaluation and reward systems and plays a key role in resource allocation.

Organisational structure aligns other CSFs by establishing sustainability-focused units, such as departments, councils, and committees, ensuring clear responsibilities and accountability. These structures integrate sustainability into performance systems, linking individual efforts to measurable goals. Regular cross-functional meetings promote collaboration between departments, while sustainability councils and remuneration committees connect top management performance to sustainability outcomes. Organisational structure also strengthens organisational culture through internal communication channels, reinforcing shared sustainability values. A well-defined structure ensures that leadership effectively prioritises financial, human, and technological resources.

Performance management reinforces the implementation of sustainability by quantifying the link between sustainability actions, performance, and financial outcomes, thereby strengthening the business case for sustainability. It provides structured data that influence organisational structure, enabling companies to make structural adjustments that better support sustainability objectives. Integrated sustainability data connect distributed personnel and expertise to actionable insights, improving operational efficiency. Additionally, performance management impacts employee motivation, as clear performance tracking and incentive structures drive engagement with sustainability initiatives.

Resources directly support the implementation of sustainability by enabling technology adoption, motivation, and organisational alignment. Financial resources facilitate investments in digital tools that enhance performance management by enabling the real-time monitoring of sustainability metrics. Knowledge resources contribute to change management and motivation, equipping employees with the skills to integrate sustainability into their daily tasks. Human resources further shape organisational culture, as recruitment and retention strategies that focus on sustainability values ensure that the workforce is aligned with long-term corporate sustainability objectives.

Stakeholder integration strengthens performance management by providing external insights that help develop sustainability metrics. It strengthens organisational culture by raising awareness and influencing external stakeholders, such as suppliers and customers, to adopt sustainability principles. In terms of resources, stakeholder relationships provide access to external capabilities that further enable sustainability initiatives.

Together, these CSFs form an interconnected system, where each factor reinforces and enables the others. This systemic interaction highlights the importance of a holistic approach to sustainability strategy implementation, ensuring that sustainability is not managed in isolation but embedded in all aspects of corporate operations.

7. Conclusions, Implications, and Limitations

This research advances academic understanding of sustainability management by providing insights into effective strategy implementation. Scholars increasingly emphasise the need to shift the focus from whether companies should adopt sustainability strategies to how they can effectively implement them in practice. Reflecting this shift, recent studies have highlighted the importance of exploring the complexities of implementation rather than simply promoting the adoption of sustainability. In order to address this gap, this research introduces a structured framework that defines CSFs and explains their interrelationships. The developed taxonomy systematically organises these factors and thereby provides a valuable foundation for analysing strategy implementation in production companies. In contrast to earlier CSF overviews that emphasise isolated factors, this taxonomy illustrates the systemic interplay among five success dimensions and, among others, distinguishes digitalisation and technology within the resource base—an increasingly relevant factor in production environments that has been overlooked in previous syntheses. The novelty of this study lies primarily in its methodological approach. While the identified CSFs are drawn from the existing literature, none of the reviewed studies developed a structured taxonomy. As far as we are aware, this is the most recent systematic literature review on the topic, and it serves as the empirical foundation for the taxonomy’s development. By applying the iterative method of Nickerson et al. [

29], this study consolidates fragmented insights into a coherent, conceptually grounded taxonomy, offering a structured basis for advancing both theoretical understanding and empirical analysis of sustainability strategy implementation.

This work provides practical value for companies by presenting a taxonomy of critical success factors (CSFs) for the implementation of corporate sustainability strategies. The taxonomy, developed through a systematic literature review, enables production companies to identify and understand the key internal factors that influence implementation efforts. It supports management in recognising which areas require strategic attention—such as organisational culture, structure, performance management, resource allocation, and stakeholder engagement—in order to improve implementation readiness and effectiveness. By structuring these factors clearly, the taxonomy helps companies navigate the organisational complexities of translating sustainability strategies into practice.

The proposed taxonomy can serve as a strategic management tool, helping decision-makers identify critical internal factors, evaluate their organisation’s implementation readiness, and prioritise initiatives that support long-term sustainability goals. More concretely, it provides guidance for companies on how to design organisational structures that support sustainability implementation, which elements of organisational culture to foster—such as commitment, collaboration, and learning orientation—how to establish performance management systems that incorporate sustainability metrics, where to direct human, financial, and technological resources, and how to effectively engage and integrate stakeholders such as employees, customers, suppliers, and partners. In doing so, the taxonomy offers actionable support for translating sustainability strategies into organisational practice. It can be applied in a range of implementation-related scenarios, such as during the planning phase of strategy execution, for internal readiness assessments or gap analyses, in guiding change management processes, or in developing training and capacity-building initiatives aimed at strengthening implementation enablers.

Beyond internal corporate benefits, the taxonomy also supports external stakeholders, such as regulatory bodies, financial institutions, local communities, and NGOs, by helping companies align with compliance requirements, investor expectations, and societal needs. This combination of academic and practical contributions makes the taxonomy useful for both researchers and businesses aiming to achieve more sustainable operations.

However, this study has certain limitations. It was constrained by a limited number of articles drawn from two databases (Scopus and ScienceDirect) and restricted to academic journal articles published in English up to September 2024. Future research could address these limitations by including a broader range of sources, languages, and publication types. Additionally, empirical validation of the interrelationships identified in this study, using approaches such as Delphi methods or real-life testing, would provide further confirmation and practical relevance. Future studies could also explore how the relative importance of CSFs varies by industry, region, and the size of organisations, offering tailored strategies for sustainability implementation. In this regard, methods such as the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) could be employed to determine the relative weights of individual CSFs in different organisational contexts, enabling a more nuanced and prioritised approach to strategy implementation. Furthermore, as sustainability strategies can differ significantly in their orientation—ranging from compliance-focused to innovation-driven—each may prioritise different aspects of sustainability. Accordingly, future research could examine how the relevance and configuration of CSFs shift across strategic profiles, supporting a more differentiated and context-sensitive approach to sustainability implementation. In addition to these points, the generalisability of our findings beyond production companies presents another important direction for future research. While this taxonomy was developed with a focus on production companies, many of the identified CSFs—such as performance management, digitalisation, and stakeholder engagement—are potentially applicable across different sectors. Future research could therefore investigate how the taxonomy can be validated and adapted to suit the specific needs of service-oriented firms, multinational corporations, and public sector organisations, thereby enhancing its relevance across a broader range of organisational settings.

Ultimately, this study underscores that corporate sustainability is a systemic effort, where the integration and alignment of CSFs are essential for the achievement of tangible economic, environmental, and social outcomes. While we have identified the interrelationships between CSFs, future research could focus on defining and quantifying the strength of these interconnections to provide deeper insights into their dynamics. Expanding the understanding of these relationships through both theoretical and practical lenses will help companies implement sustainability strategies more effectively, thereby driving long-term success in an increasingly complex and interconnected world.