Dynamic Identification of Relative Poverty Among Chinese Households Using the Multiway Mahalanobis–Taguchi System: A Sustainable Livelihoods Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Construction of the Index System for Identifying Relative Poverty from the Perspective of Sustainable Livelihoods

3. Construction of the Multiway Mahalanobis–Taguchi System

3.1. Proposal of the Multiway Mahalanobis–Taguchi System

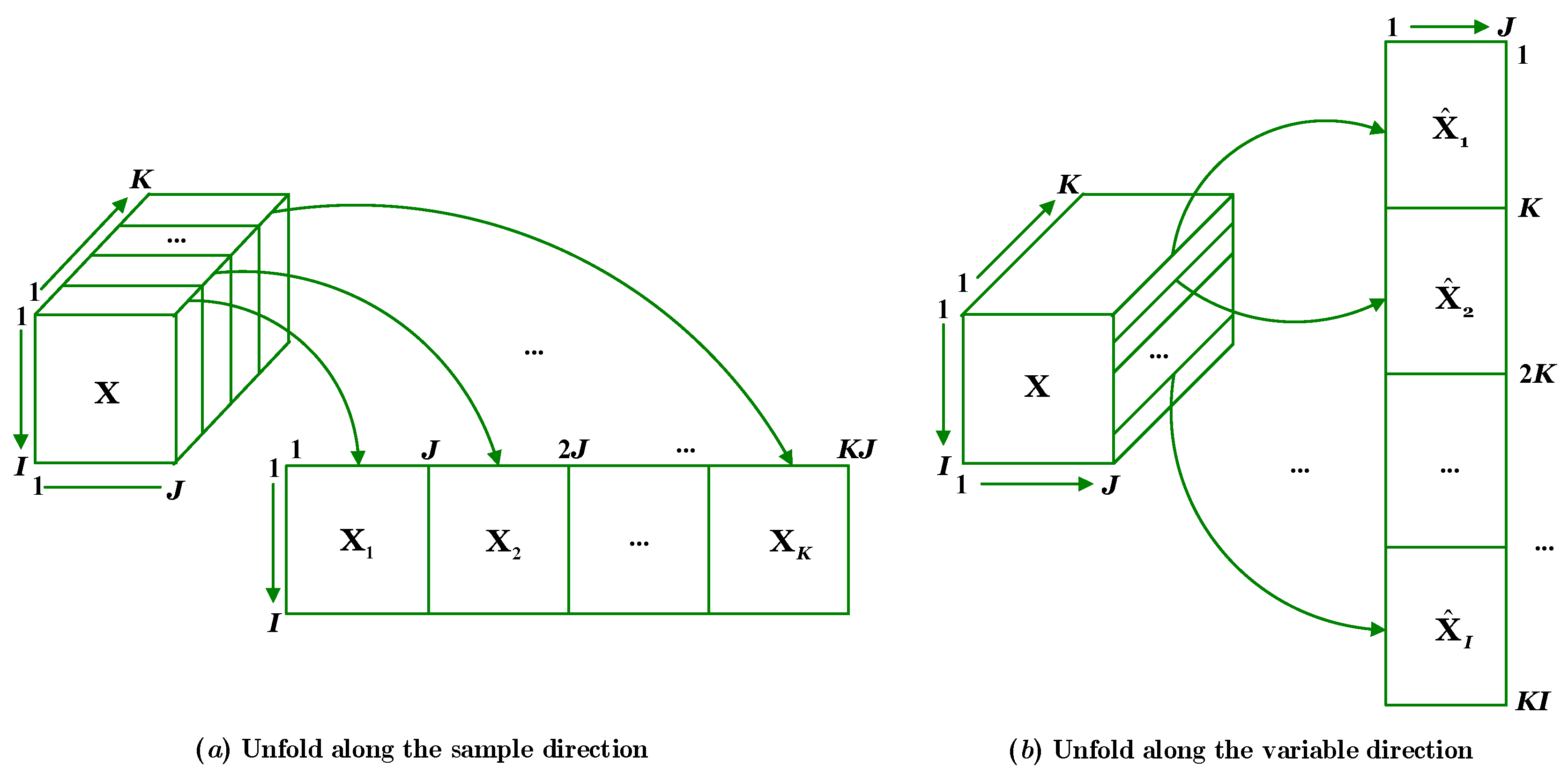

3.2. Multiway Mahalanobis Distance

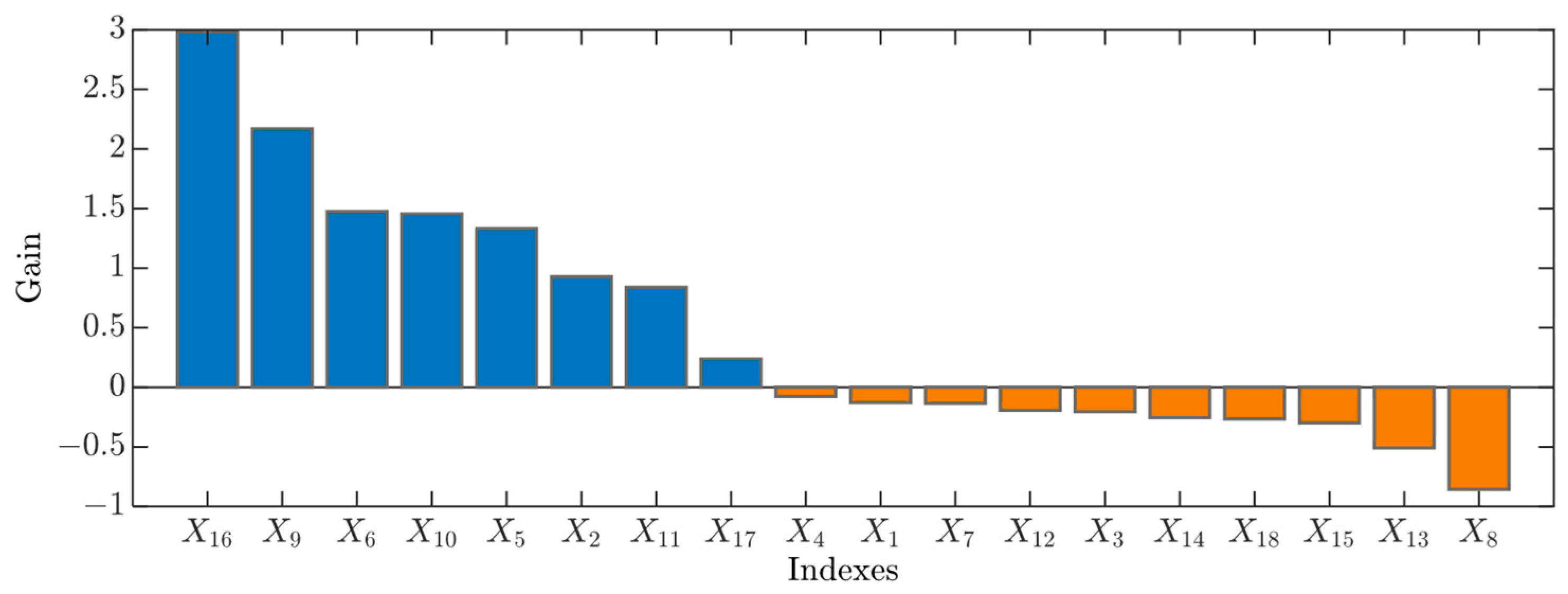

3.3. Taguchi Orthogonal Experimental Design

3.4. Calculation Steps

4. Case Study Application

4.1. Data Source and Sampling Methods

4.2. Evaluation Indexes for Identification Performance

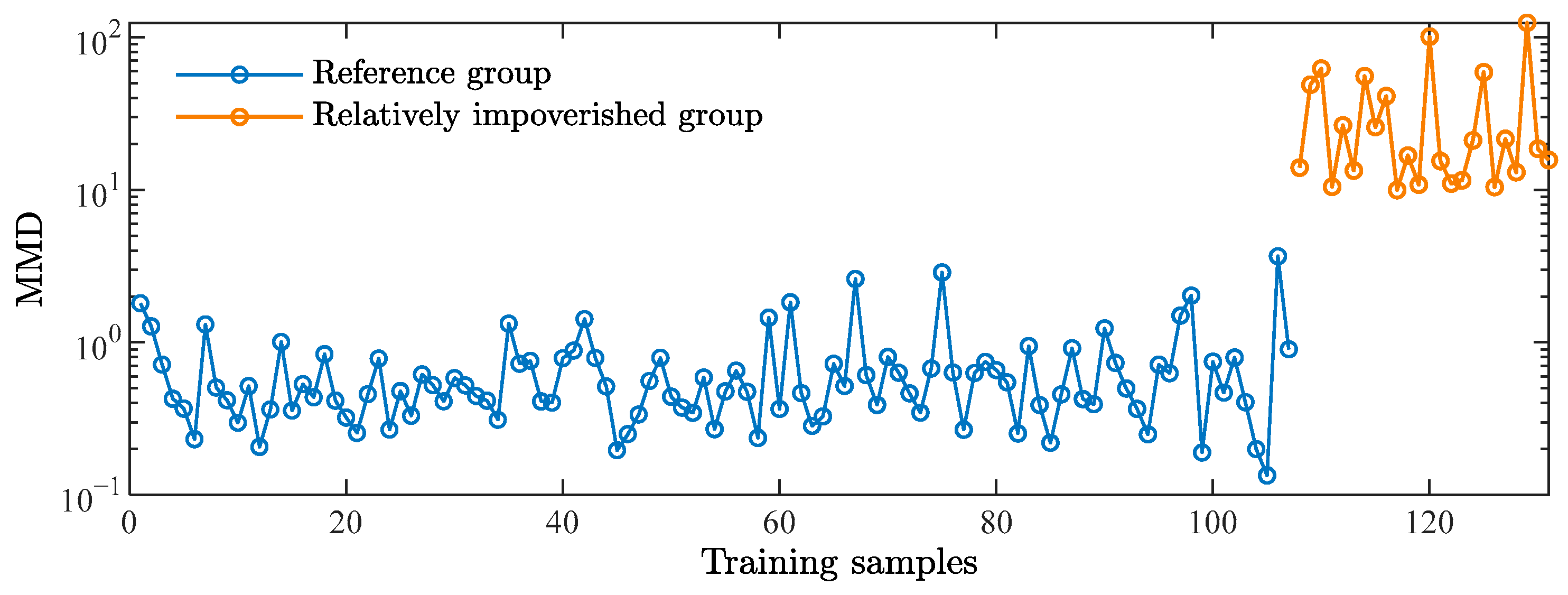

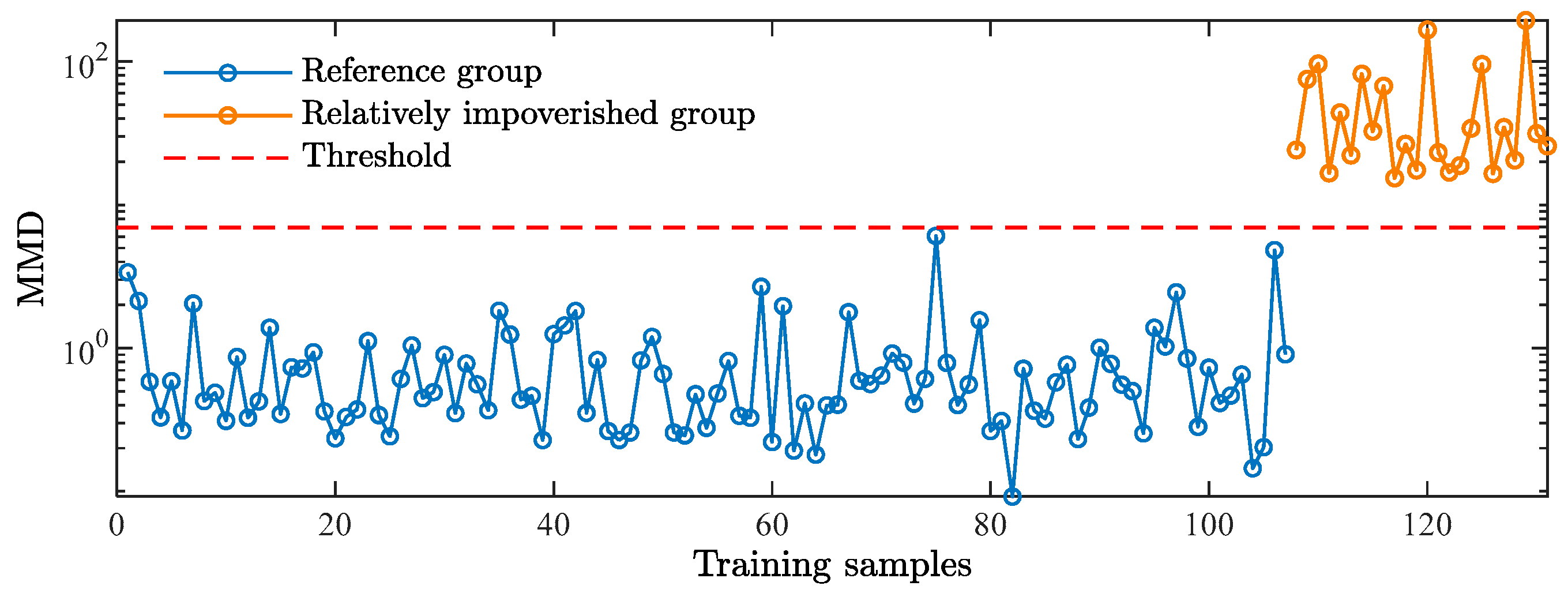

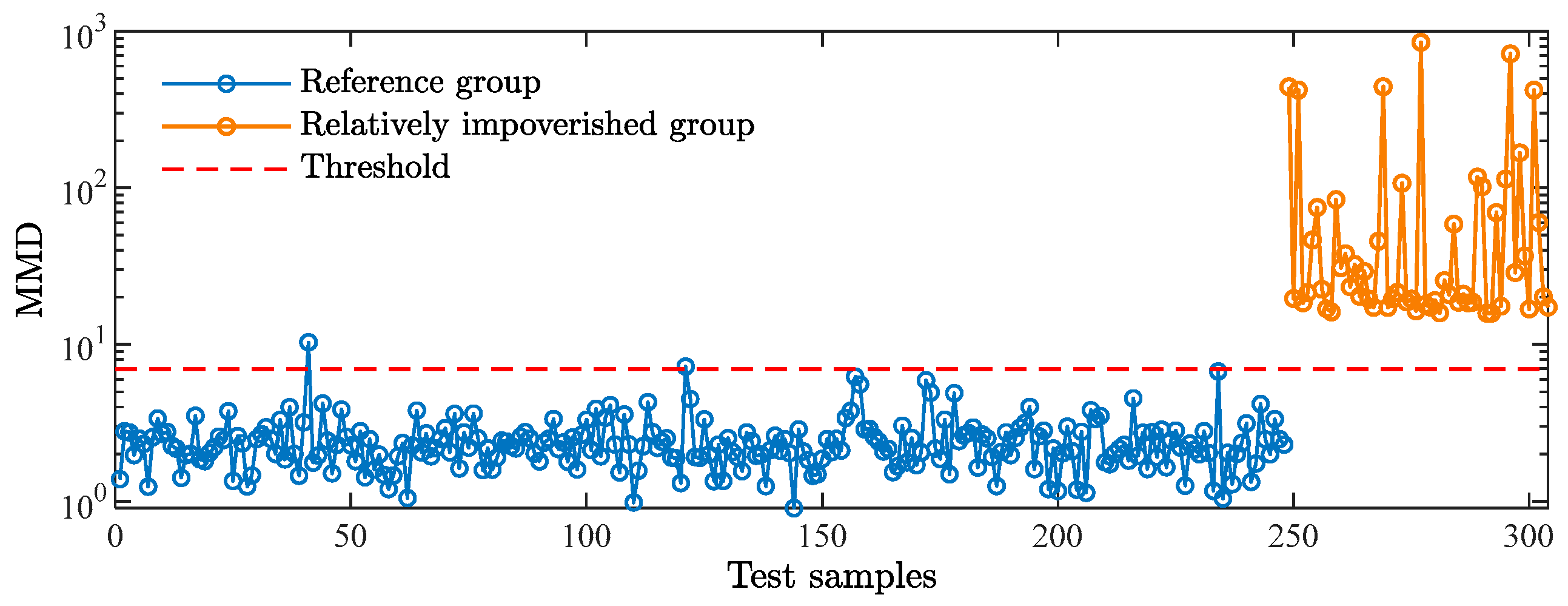

4.3. Identification Threshold

4.4. Identification Steps

4.5. Method Comparison

4.6. Discussion

5. Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

5.1. Conclusions

5.2. Policy Recommendations

- In eastern regions: The focus should be placed on addressing social exclusion and an unequal access to digital resources. For example, a dynamic monitoring system should be established to cover vocational skill training, the accessibility of public services, and the penetration rate of digital skills. Enterprises should be encouraged to provide digital employment training for migrant populations through fiscal subsidies, in order to narrow the gap in access to digital resources.

- In western regions: The focus should be on ecological vulnerability and inadequate infrastructure (e.g., land degradation and natural disaster risks). For example, natural capital indices should be linked to ecological compensation mechanisms; house-holds’ resilience can be enhanced through targeted subsidies; and infrastructure upgrades should be prioritized in high-risk areas.

- Short-term (addressing sudden shocks): Provide rapid assistance to households impoverished by natural disasters or economic fluctuations through emergency financial tools (e.g., low-interest loans, disaster insurance, linked to financial capital indexes).

- Medium-term (breaking the intergenerational transmission of poverty): Prioritize investment in the regeneration of human capital, such as linking children’s school enrollment rates with education subsidies to ensure a continuous education for children in poor households; provide employment placement support for households participating in vocational training to enhance their long-term income capacity.

- Long-term (building sustainable livelihoods): Integrate livelihood environment indexes (e.g., infrastructure, public services) to promote “ecologically friendly industries” (e.g., eco-tourism, organic agriculture) in ecologically fragile areas to reduce the reliance on traditional natural resources, while expanding agricultural product sales channels through digital technologies (e.g., e-commerce platforms) to enhance the accumulation of physical capital (durable consumer goods).

- First, integrate multi-source data (e.g., civil, educational, medical insurance, remote sensing monitoring data) to calculate household poverty levels through MMD.

- Second, set early-warning thresholds based on Youden’s index to trigger warnings for households with an MMD exceeding the threshold, distinguishing between “high-risk poverty return” and “structural poverty” groups.

- Finally, automatically match temporary relief policies to high-risk poverty return households, such as those facing sudden medical expenses due to illness. For structurally poor households with long-term human capital shortages, push “education + employment” combined assistance programs.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yaohong, W.; Firdaus, R.B.R.; Xu, J.; Dharejo, N.; Jun, G. China’s Rural Revitalization Policy: A PRISMA 2020 Systematic Review of Poverty Alleviation, Food Security, and Sustainable Development Initiatives. Sustainability 2025, 17, 569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A. Development as Freedom; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Silver, H. Social Exclusion and Social Solidarity: Three Paradigms. Int. Lab. Rev. 1994, 133, 52. [Google Scholar]

- Alkire, S.; Foster, J. Counting and multidimensional poverty measurement. J. Public Econ. 2011, 95, 476–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Sicular, T. The Distribution of Household Income in China: Inequality, Poverty and Policies. China Q. 2014, 217, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C.; Li, S.; Sicular, T. The Long-Term Evolution of National Income Inequality and Rural Poverty in China. China Econ. Rev. 2020, 62, 101465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, J.E. Absolute versus Relative Poverty. Am. Econ. Rev. 1998, 88, 335–341. [Google Scholar]

- He, X.; Xi, H.; Li, X. Multi-Dimensional Decomposition, Measurement, and Governance Mechanism of Relative Poverty in Chinese Households under the Goal of Common Prosperity: Empirical Analysis Based on CFPS2020 Data. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, R.; Li, P. A Study on the Measurement of Relative Poverty in Developing Countries with Large Populations. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X. On the Relationship Between Income Poverty and Multidimensional Poverty in China. In Multidimensional Poverty Measurement: Theory and Methodology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 85–106. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S. Dovetailing Poverty Alleviation with Rural Revitalization. In Poverty Alleviation and Targeted Measures: Theory and Practice; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025; pp. 267–298. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, G.; Hu, X.; Liu, W. China’s Poverty Reduction Miracle and Relative Poverty: Focusing on the Roles of Growth and Inequality. China Econ. Rev. 2021, 68, 101643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parolin, Z.; Pintro-Schmitt, R.; Esping-Andersen, G.; Fallesen, P. Intergenerational Persistence of Poverty in Five High-Income Countries. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2024, 9, 254–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.R. Regional Inequality and Poverty in China. World Dev. 2018, 112, 231–245. [Google Scholar]

- Bourguignon, F. The Globalization of Inequality; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett, C.B.; Carter, M.R. The Economics of Poverty Traps and Persistent Poverty: Empirical and Policy Implications. J. Dev. Stud. 2013, 49, 976–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravallion, M. The Debate on Globalization, Poverty and Inequality: Why Measurement Matters. Int. Aff. 2003, 79, 739–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luzzi, G.F.; Flückiger, Y.; Weber, S. A Cluster Analysis of Multidimensional Poverty in Switzerland. In Quantitative Approaches to Multidimensional Poverty Measurement; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 63–79. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, L.; Sun, S. Can China’s New Rural Pension Scheme Alleviate the Relative Poverty of Rural Households? An Empirical Analysis Based on the PSM-DID Method. Aust. Econ. Pap. 2023, 62, 396–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruejols, L.; Wang, H.; Zhao, Q.; Bai, Y.; Zhang, L. Comparison of Machine Learning Predictions of Subjective Poverty in Rural China. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2023, 15, 379–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Liu, Y.; Hu, P.; Ding, S.; Gao, S.; Zhang, M. What Influence Farmers’ Relative Poverty in China: A Global Analysis Based on Statistical and Interpretable Machine Learning Methods. Heliyon 2023, 9, e19525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Guo, L. Multi-Label Classification of Chinese Rural Poverty Governance Texts Based on XLNet and Bi-LSTM Fused Hierarchical Attention Mechanism. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 7377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarry, R.; Chaumont, M.; Berti-Équille, L.; Subsol, G. Assessment of CNN-Based Methods for Poverty Estimation from Satellite Images. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Pattern Recognition, Virtual, 10–11 January 2021; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 550–565. [Google Scholar]

- Goodfellow, I.; Bengio, Y.; Courville, A. Deep Learning; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- DFID. Sustainable Livelihoods Guidance Sheets; Department for International Development (DFID): London, UK, 1999; Volume 445, p. 710.

- Natarajan, N.; Newsham, A.; Rigg, J.; Suhardiman, D. A Sustainable Livelihoods Framework for the 21st Century. World Dev. 2022, 155, 105898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taguchi, G.; Taguchi, G.; Jugulum, R. The Mahalanobis-Taguchi Strategy: A Pattern Technology System; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2002; ISBN 0471023337. [Google Scholar]

- Taguchi, G.; Jugulum, R. New Trends in Multivariate Diagnosis. Indian J. Stat. 2000, 62B, 233–248. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C.F.J.; Hamada, M.S. Experiments: Planning, Analysis, and Optimization, 2nd ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bock, H.H.; Diday, E. Analysis of Symbolic Data; Springer: Paris, France, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Malerba, D.; Esposito, F.; Gioviale, V.; Tamma, V. Comparing Dissimilarity Measures for Symbolic Data Analysis. Proc. Exch. Technol. Know-How New Technol. Stat. 2001, 1, 473–481. [Google Scholar]

- Rojas, M. Experienced Poverty and Income Poverty in Mexico: A Subjective Well-Being Approach. World Dev. 2008, 36, 1078–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Vliet, O.; Wang, C. Social Investment and Poverty Reduction: A Comparative Analysis across Fifteen European Countries. J. Soc. Policy 2015, 44, 611–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepe, M.S. The Statistical Evaluation of Medical Tests for Classification and Prediction; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Barandela, R.; Sánchez, J.S.; García, V.; Rangel, E. Strategies for Learning in Class Imbalance Problems. Pattern Recognit. 2003, 36, 849–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Z.P.; Li, Y.W.; Fatima, N. A Theoretical Survey on Mahalanobis-Taguchi System. Measurement 2019, 136, 501–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youden, W.J. Statistical Methods for Chemists; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1951. [Google Scholar]

- Wooldridge, J.M. Two-way fixed effects, the two-way Mundlak regression, and difference-in-differences estimators. SSRN Electron. J. 2021, 1–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, T.; Zhang, Q.; Zhao, L.; Lin, Y.S.; Peng, M.L.; Gong, J.; Huang, X.J. Long Short-Term Memory with Dynamic Skip Connections. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Honolulu, HI, USA, 27 January–1 February 2019; Volume 33, pp. 6481–6488. [Google Scholar]

| Dimension | Index | Screening Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Human Capital | Average years of education for adults (X1) | Reflect the long-term impact of the knowledge reserve on income-earning ability and block the intergenerational transmission of poverty. |

| Health status of household members (X2) | Measure the direct weakening of diseases in terms of labor capacity, echoing the health–poverty alleviation policy. | |

| School enrollment rate for children of school age (X3) | Monitor educational equity and prevent the intergenerational transmission of capability poverty. | |

| Participation rate in vocational skill training (X4) | Meet the requirements of industrial upgrading and improve the adaptability to non-agricultural employment. | |

| Financial Capital | Annual per capita household income (X5) | Serve as a core explicit index for accessing economic resources. |

| Family savings/debt ratio (X6) | Warn of debt risks and identify groups with weak economic resilience. | |

| Natural Capital | Area and quality of cultivated land (X7) | Reflect the livelihood foundation of agriculture-based households and align with policies such as returning farmland to forests. |

| Degree of dependence on natural resources (X8) | Monitor the pressure on alternative livelihoods in ecologically fragile areas caused by environmental policies (e.g., logging bans). | |

| Physical Capital | Compliance rate of housing conditions (X9) | Housing is the core of basic living security, directly affecting health and safety. Dilapidated or simple-structured houses are vulnerable to natural disasters, exacerbating vulnerability to poverty. |

| Accessibility of safe drinking water (X10) | Access to safe drinking water is fundamental to health and productivity. The lack of drinking water increases the risk of diseases and the cost of living. | |

| Coverage rate of sanitary facilities (X11) | Poor sanitation facilities are prone to the transmission of disease, increasing the burden of medical expenses. | |

| Number of durable consumer goods (X12) | Household appliances and transportation tools reflect the convenience of life and the ability to resist risks. | |

| Transportation convenience (X13) | Transportation conditions affect access to employment opportunities, as well as the accessibility of education and healthcare resources, limiting social participation. | |

| Social Capital | Strength of social network support (X14) | Social networks serve as an informal safeguard for families to cope with sudden risks (e.g., illness, unemployment), reflecting the mutual aid capacity of social relationships. |

| Degree of participation in community organizations (X15) | The ability to undertake collective action enhances opportunities for the acquisition of resources and policy benefits through organizations such as cooperatives and mutual aid associations. | |

| Livelihood Environment | Degree of infrastructure completion (X16) | Infrastructure is the foundation of economic development, directly affecting production efficiency and market access. |

| Accessibility of public services (X17) | The accessibility of public services such as education, medical care, and markets reduces the inequality of opportunities and lowers living costs. | |

| Degree of exposure to natural disaster risks (X18) | Environmental vulnerability directly threatens the stability of livelihoods, especially for household’s dependent on agriculture and natural resources. |

| Experiment | The MMDs of Abnormal Samples | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 2 | … | |||

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | … | ||||

| 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | … | ||||

| 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | … | ||||

| 4 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | … | ||||

| 5 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | … | ||||

| 6 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | … | ||||

| 7 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | … | ||||

| 8 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | … | ||||

| Dimension | Index | Explanation and Assignment |

|---|---|---|

| Human Capital | Average years of education for adults (X1) | The average years of education of the main labor force in a household reflect the household’s capacity to generate income through knowledge and skills. A low level of education may lead to the intergenerational transmission of poverty. (more than 16 years = 5, 12–16 years = 4, 9–12 years = 3, 6–9 years = 2, less than 6 years = 1) |

| Health status of household members (X2) | The proportion of household members suffering from chronic diseases or disabilities. The health level directly affects the labor capacity and the burden of medical expenditure. (%) | |

| School enrollment rate for children of school age (X3) | The actual enrollment rate of children aged 6 to 15 in the household, which measures the fairness of educational opportunities. A low enrollment rate may indicate a shortage of future human capital. (%) | |

| Participation rate in vocational skill training (X4) | The proportion of household members participating in vocational skill training reflects the household’s ability to improve employment opportunities through skill enhancement. (%) | |

| Financial Capital | Annual per capita household income (X5) | The annual average value of the total household income divided by the number of household members directly reflects the ability to acquire economic resources and is a core measurement standard for poverty. |

| Family savings/debt ratio (X6) | The proportion of household savings or liabilities to the annual income. A high debt ratio can indicate economic vulnerability and debt risks. (%) | |

| Natural Capital | Area and quality of cultivated land (X7) | The area of arable land owned by a household and its soil fertility level represent the foundation of their livelihood for agriculture-dependent households; land scarcity may lead to poverty. (more than 5 mu with high fertility = 5, 3–5 mu with high fertility = 4, 1–3 mu with medium fertility = 3, less than 1 mu with low fertility = 2, no land or barren land = 1) |

| Degree of dependence on natural resources (X8) | The proportion of household income depends on natural resources such as forestry and fisheries; over-reliance on natural resources makes households vulnerable to environmental changes. (%) | |

| Physical Capital | Compliance rate of housing conditions (X9) | Housing structure (e.g., brick–concrete or reinforced concrete) and whether the per capita living area meets standards reflect the level of basic living security. (reinforced concrete/≥15 m2 = 5, brick–concrete/12–15 m2 = 4, brick–timber/8–12 m2 = 3, simple structure/5–8 m2 = 2, dilapidated house/per capita area < 5 m2 = 1) |

| Accessibility of safe drinking water (X10) | Whether a household can consistently access drinking water that meets sanitary standards; the lack of safe drinking water poses health risks and increases living costs. (indoor direct supply = 5, walking < 30 min = 4, walking 30–60 min = 3, walking > 1 h to fetch water = 2, no stable water source = 1) | |

| Coverage rate of sanitary facilities (X11) | Whether a household has access to a private toilet (e.g., flush toilet); poor sanitation conditions may increase the risk of disease. (private flush toilet = 5, shared flush toilet = 4, simple dry toilet = 3, open-air toilet = 2, no toilet = 1) | |

| Number of durable consumer goods (X12) | The number of household appliances (e.g., refrigerator, washing machine) and means of transportation (e.g., electric vehicles, cars) reflects the level of convenience in life and resilience to risks. (≥7 items, including high-value assets such as cars = 5, 5–6 items = 4, 3–4 items = 3, 1–2 items = 2, 0 items = 1) | |

| Transportation convenience (X13) | The walking time from a household to the nearest public transportation stop, which affects access to employment opportunities and social participation. (≤5 min = 5, 5–15 min = 4, 15–30 min = 3, 30–60 min = 2, >60 min = 1) | |

| Social Capital | Strength of social network support (X14) | Whether a household can receive financial or material assistance from relatives, friends, or the community in emergencies; social networks are a critical resource for risk management. (abundant and reliable support = 5, stable and basic support = 4, regular but partial support = 3, occasional and minimal support = 2, no support at all = 1) |

| Degree of participation in community organizations (X15) | Whether household members participate in organizations such as cooperatives or mutual aid groups; the capacity for collective action influences access to resources and opportunities to benefit from policies. (active participation in ≥2 organizations = 5, regular participation in 1 organization = 4, occasional participation in activities = 3, past participation but has withdrawn = 2, no participation = 1) | |

| Livelihood Environment | Degree of infrastructure completion (X16) | The level of infrastructure coverage in the community, including roads, electricity, and communication networks; underdeveloped infrastructure limits economic development opportunities. (fully paved roads, stable electricity, and high-speed internet = 5; access to electricity and internet with partially paved roads = 4; fully paved roads and stable electricity but no internet = 3; partially paved roads and unstable electricity = 2; no paved roads and frequent power outages = 1) |

| Accessibility of public services (X17) | The distance or travel time from a household to the nearest school, hospital, and market; insufficient access to public services increases living costs and exacerbates inequality. (all services within ≤1 km = 5, all services within 1–3 km = 4, all services within 3–5 km = 3, some services within 5–10 km = 2, all services >10 km = 1) | |

| Degree of exposure to natural disaster risks (X18) | The frequency and extent of losses caused by natural disasters, such as floods and droughts, in the region over the past five years. Environmental vulnerability threatens livelihood stability. (no disaster records = 5, one minor disaster = 4, one disaster with 10–30% loss = 3, two disasters with >30% income loss = 2, ≥3 major disasters in the past five years = 1) |

| Poverty County | Reference Group | Relatively Impoverished Group | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 355 | 80 | 435 |

| B | 140 | 83 | 223 |

| C | 135 | 102 | 237 |

| Total | 630 | 265 | 895 |

| Experiment | Index | Relatively Impoverished Samples | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| … | ||||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | … | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 1 | 2 | … | 24 | ||

| 1 | 2 | 2 | … | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0.1613 | 2.5434 | … | 0.9366 | 1.0922 |

| 2 | 2 | 2 | … | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0.9833 | 1.9016 | … | 0.7165 | 0.9194 |

| 3 | 2 | 2 | … | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0.3098 | 2.4973 | … | 0.1728 | 0.8391 |

| 4 | 2 | 2 | … | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0.1421 | 0.2575 | … | 0.2410 | −2.3333 |

| 5 | 2 | 2 | … | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1.2026 | 1.6602 | … | 1.9966 | 3.1094 |

| 6 | 2 | 1 | … | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1.8406 | 1.9633 | … | 0.7212 | 1.1410 |

| 7 | 2 | 1 | … | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0.6463 | 0.5173 | … | 1.0173 | 2.3984 |

| 8 | 2 | 1 | … | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2.4517 | 6.3508 | … | 0.8380 | 6.0300 |

| 9 | 2 | 1 | … | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2.6194 | 11.3449 | … | 1.6978 | 6.8837 |

| 10 | 2 | 1 | … | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0.5962 | 1.4079 | … | 0.3471 | 2.2859 |

| 11 | 1 | 2 | … | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0.8248 | 0.9760 | … | 0.6427 | 3.2936 |

| 12 | 1 | 2 | … | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0.1621 | 0.6307 | … | 0.5013 | −0.0161 |

| 13 | 1 | 2 | … | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2.7658 | 15.4974 | … | 2.6709 | 4.8211 |

| 14 | 1 | 2 | … | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0.8102 | 4.6317 | … | 0.1507 | 1.8118 |

| 15 | 1 | 2 | … | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.2420 | 0.5824 | … | 0.2939 | 0.8105 |

| 16 | 1 | 1 | … | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0.2568 | 1.3467 | … | 0.8638 | 2.3034 |

| 17 | 1 | 1 | … | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0.3237 | 0.4912 | … | 0.9723 | 1.0161 |

| 18 | 1 | 1 | … | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1.8383 | 1.8746 | … | 0.6600 | 2.1084 |

| 19 | 1 | 1 | … | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0.1281 | 0.3894 | … | 0.7938 | −1.5811 |

| 20 | 1 | 1 | … | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2.2584 | 13.2092 | … | 1.8052 | 6.5009 |

| Sample Data | Classification Method | Evaluation Indexes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Sensitivity | Specificity | G-Means | ||

| Poverty County A | MMTS | 0.95 ± 0.02 | 0.93 ± 0.03 | 0.97 ± 0.01 | 0.96 ± 0.02 |

| Two-way FE | 0.88 ± 0.12 | 0.85 ± 0.10 | 0.90 ± 0.06 | 0.87 ± 0.08 | |

| Dynamic LSTM | 0.90 ± 0.10 | 0.87 ± 0.09 | 0.92 ± 0.05 | 0.90 ± 0.07 | |

| Poverty County B | MMTS | 0.96 ± 0.02 | 0.94 ± 0.02 | 0.98 ± 0.01 | 0.97 ± 0.01 |

| Two-way FE | 0.89 ± 0.15 | 0.86 ± 0.12 | 0.91 ± 0.07 | 0.88 ± 0.10 | |

| Dynamic LSTM | 0.91 ± 0.12 | 0.88 ± 0.11 | 0.93 ± 0.06 | 0.91 ± 0.08 | |

| Poverty County C | MMTS | 0.97 ± 0.01 | 0.95 ± 0.02 | 0.98 ± 0.01 | 0.97 ± 0.01 |

| Two-way FE | 0.90 ± 0.18 | 0.87 ± 0.15 | 0.92 ± 0.08 | 0.89 ± 0.12 | |

| Dynamic LSTM | 0.92 ± 0.14 | 0.89 ± 0.13 | 0.94 ± 0.07 | 0.92 ± 0.09 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Chen, W. Dynamic Identification of Relative Poverty Among Chinese Households Using the Multiway Mahalanobis–Taguchi System: A Sustainable Livelihoods Perspective. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5384. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125384

Chang Z, Wang Y, Chen W. Dynamic Identification of Relative Poverty Among Chinese Households Using the Multiway Mahalanobis–Taguchi System: A Sustainable Livelihoods Perspective. Sustainability. 2025; 17(12):5384. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125384

Chicago/Turabian StyleChang, Zhipeng, Yuehua Wang, and Wenhe Chen. 2025. "Dynamic Identification of Relative Poverty Among Chinese Households Using the Multiway Mahalanobis–Taguchi System: A Sustainable Livelihoods Perspective" Sustainability 17, no. 12: 5384. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125384

APA StyleChang, Z., Wang, Y., & Chen, W. (2025). Dynamic Identification of Relative Poverty Among Chinese Households Using the Multiway Mahalanobis–Taguchi System: A Sustainable Livelihoods Perspective. Sustainability, 17(12), 5384. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125384