Factors Affecting the Implementation of Green Supply Chain in Companies in Indonesia: A Qualitative Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

- How do senior logistics managers conceptualize and apply GSCM within Indonesian supply chain operations?

- What are the most critical internal and external barriers hindering GSCM implementation at the operational level?

- What organizational motivations and contextual factors most significantly drive or constrain GSCM initiatives in the logistics sector?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Sustainability

2.2. Green Supply Chain

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Design

3.2. Procedure

3.3. Population and Sample

3.4. Source of Data

3.5. Data Analysis

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Respondent Demographics

4.2. Analysis of Findings

4.2.1. How Is Green Supply Chain Management (GSCM) Implemented in Companies in Indonesia?

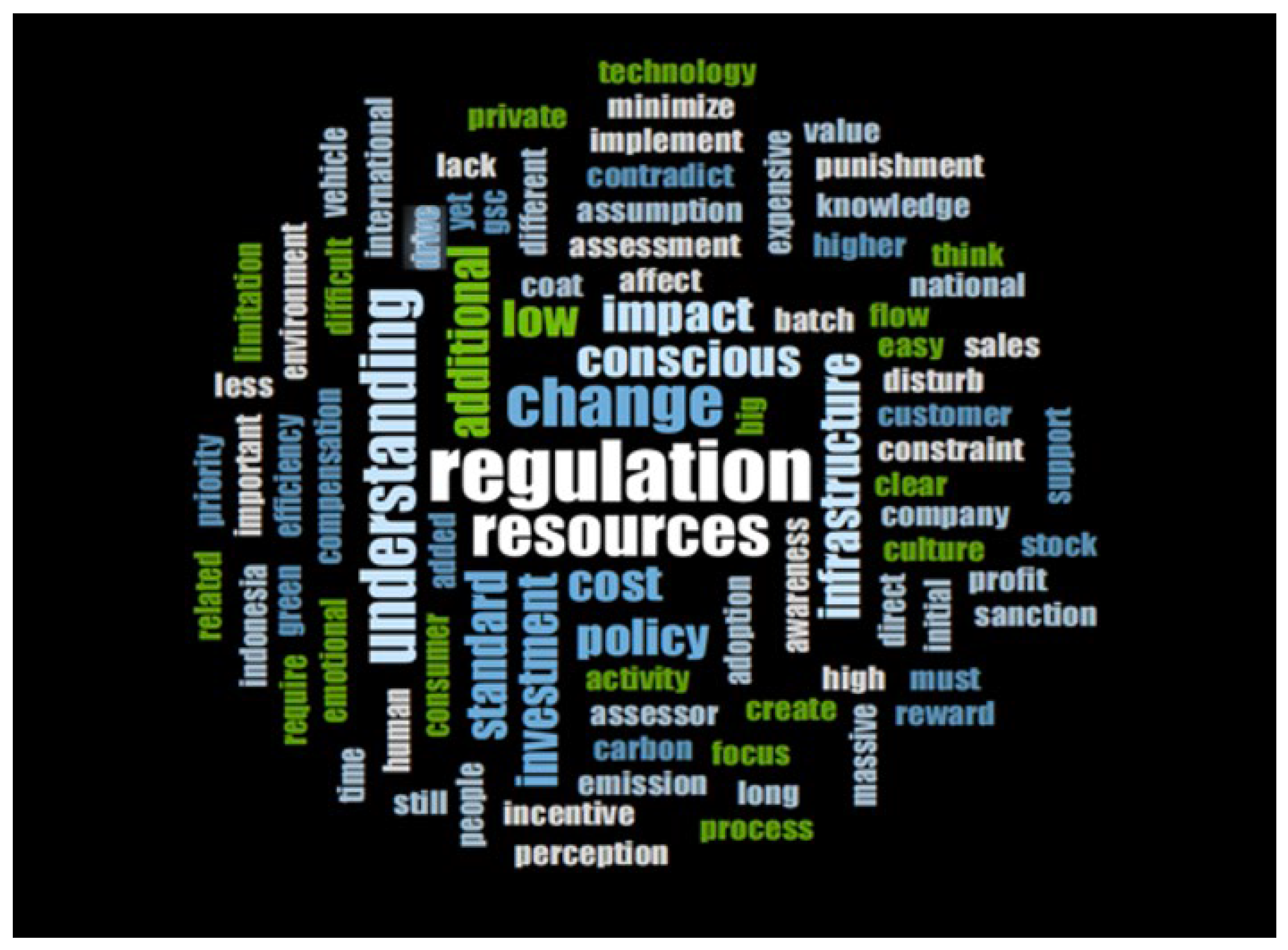

4.2.2. Current Challenges and Barriers to the Implementation of GSCM in Companies

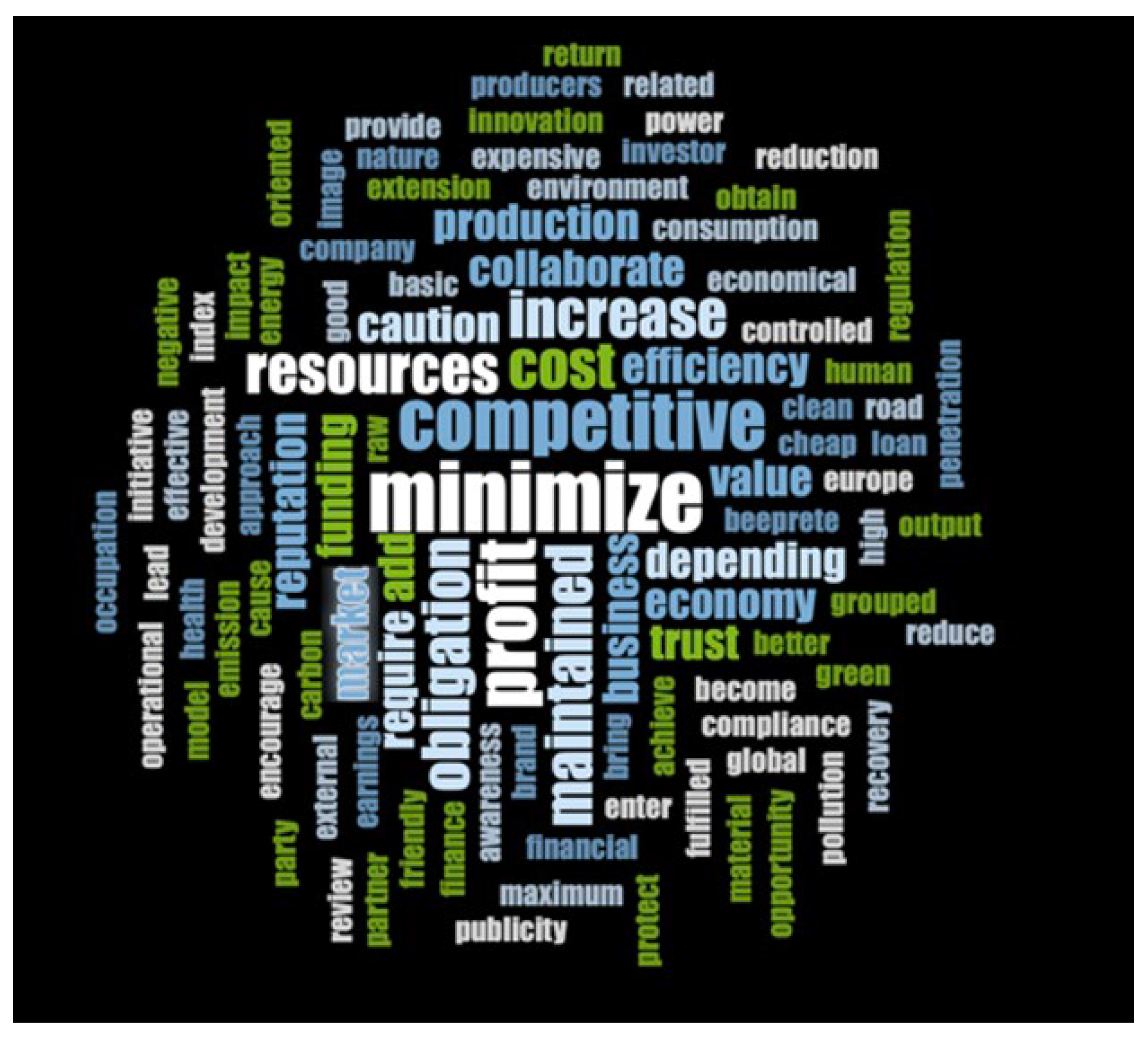

4.2.3. The Key Factors Influencing the Implementation of GSCM, and How It Has Been Applied in Companies Thus Far

- Energy Transition and Alternative Fuels

- 2.

- Emissions Reduction and Pollution Control

- 3.

- Infrastructure and Technological Innovation

- 4.

- Waste Reduction and Resource Efficiency

- 5.

- Ethical Sourcing and Supplier Evaluation

- 6.

- Technology-Driven Monitoring and Reporting

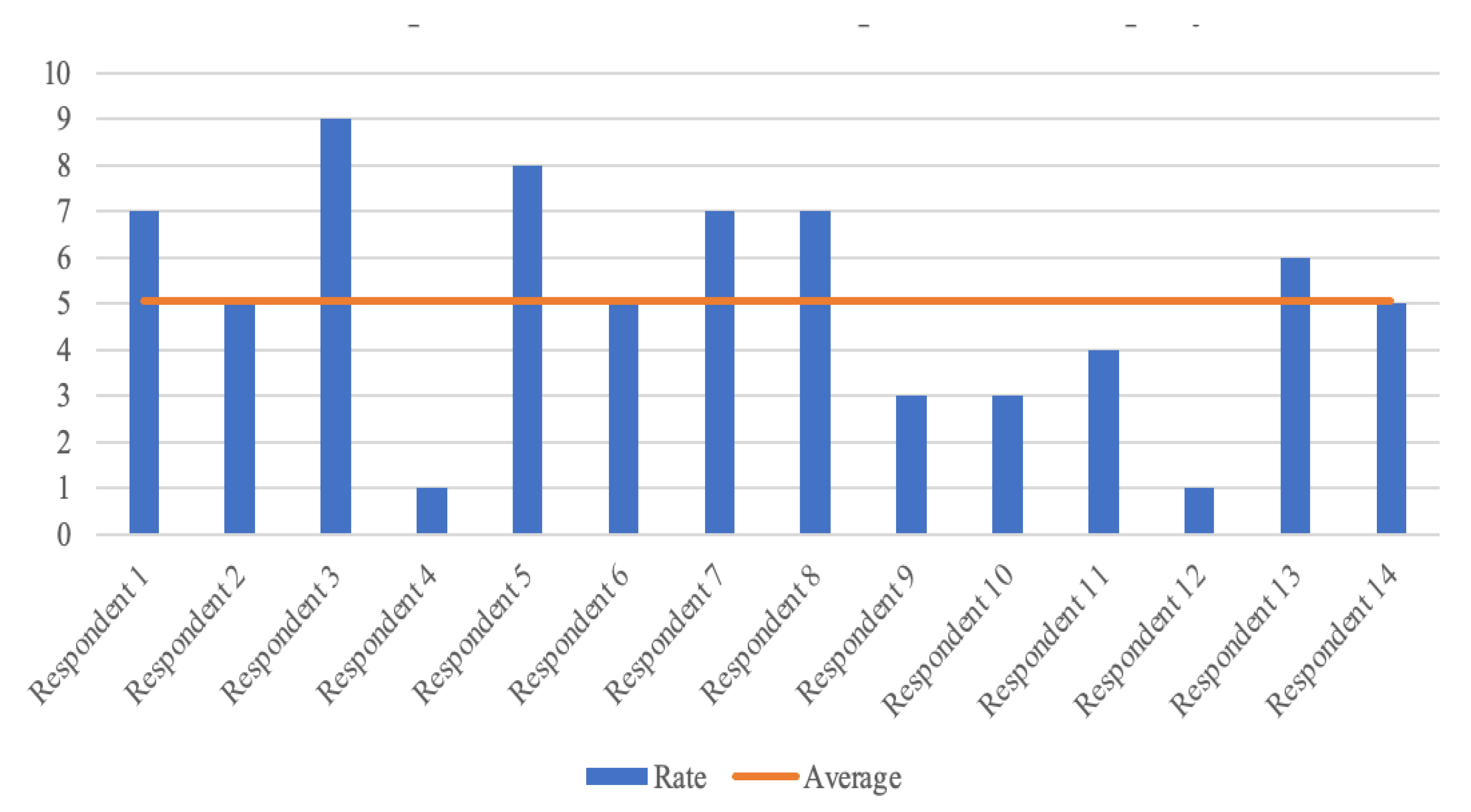

4.2.4. How Significant Is the Implementation of GSCM in Companies?

4.3. Discussion

5. Conclusions

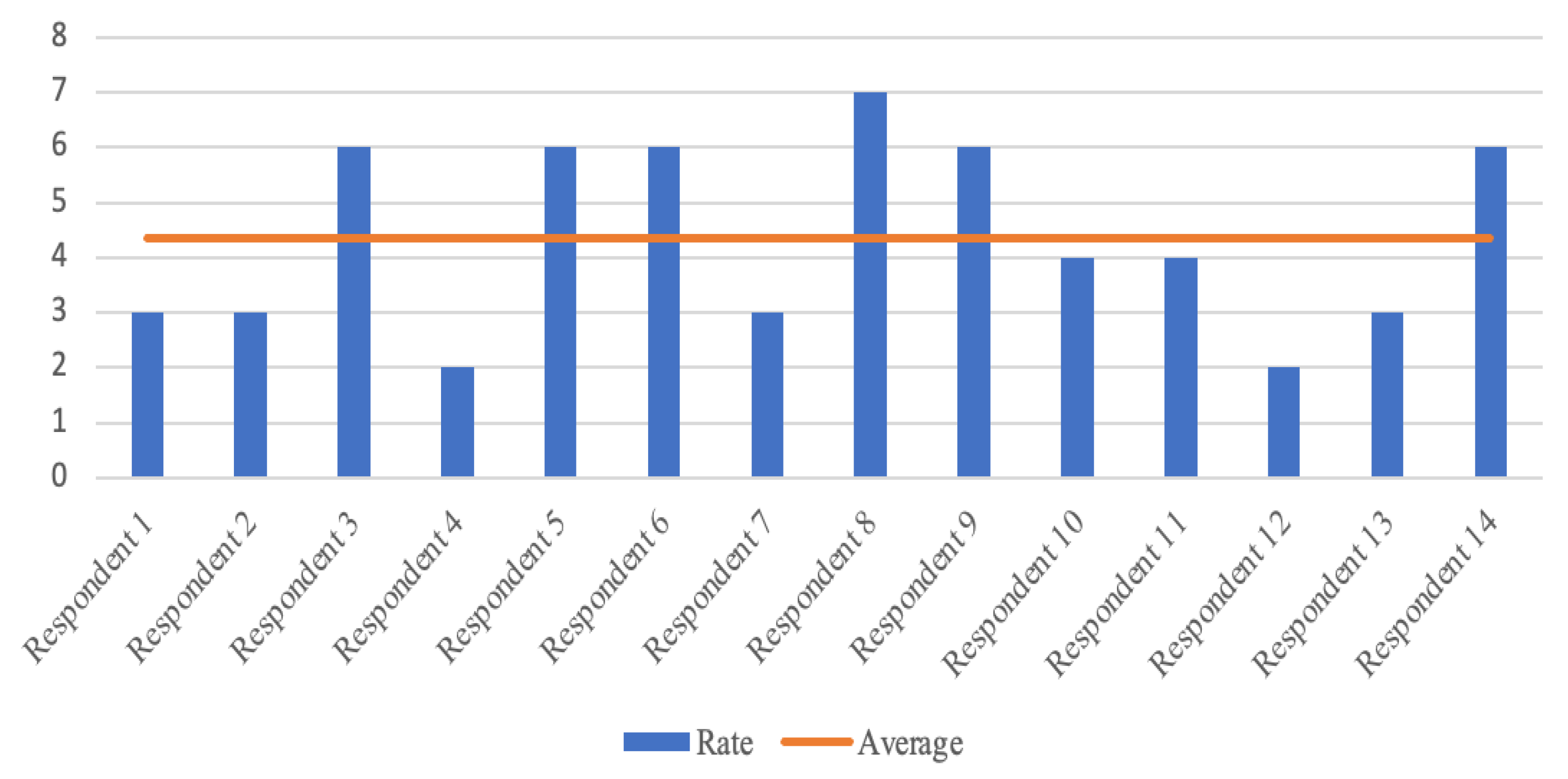

- Respondents generally view green supply chain practices as environmentally focused efforts, such as recycling to reduce environmental impact, aligning with theoretical definitions, but some express conceptual confusion, seeing green supply chains as short-term initiatives within the broader, more strategic and long-term framework of sustainable supply chains. GSCM adoption remains limited, with an average perceived implementation score of 4.36 out of 10.

- Key barriers include financial constraints, a lack of regulatory enforcement, limited technical knowledge, and insufficient customer pressure.

- Company size and exposure to international collaboration significantly influence GSCM engagement. This supports our working hypothesis that larger and internationally exposed firms are more proactive in adopting sustainable practices. Smaller or domestically focused companies often lag due to restricted access to resources, strategic frameworks, or external incentives.

5.1. Theoritical Implications

5.2. Managerial Implication

5.3. Limitations and Further Research Direction

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sanders, N.R.; Wood, J.D. Foundations of Sustainable Business; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, M. Supply Chain and Its Environmental Impact. 2015. Available online: https://www.morethanshipping.com/supply-chain-and-its-environmental-impact/ (accessed on 18 July 2024).

- Almond, R.E.A.; Grooten, M.; Petersen, T. WWF (2020) Living Planet Report 2020—Bending the Curve of Biodiversity Loss. 2020. Available online: https://www.wwf.org.uk/sites/default/files/2020-09/LPR20_Full_report.pdf (accessed on 18 July 2024).

- Ingwersen, W.; Li, M. Supply Chain Greenhouse Gas Emission Factors for US Industries and Commodities. 2020. Available online: https://cfpub.epa.gov/si/si_public_record_report.cfm?Lab=CESER&dirEntryId=349324 (accessed on 18 July 2024).

- Haar, J.; Sánchez-Flores, R.B.; Courtemanche, P. The Status, Policies and Outlook for Green Supply Chains in North America; Wilson Center: Washington, DC, USA, 2023; Available online: https://www.wilsoncenter.org/article/status-policies-and-outlook-green-supply-chains-north-america (accessed on 18 July 2024).

- Mustafi, M.A.A.; Dong, Y.-J.; Hosain, M.S.; Amin, M.B.; Rahaman, M.A.; Abdullah, M. Green Supply Chain Management Practices and Organizational Performance: A Mediated Moderation Model with Second-Order Constructs. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holling, H.; Backhaus, L. A Meta-Analysis of Green Supply Chain Management Practices and Firm Performance. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battistella, C.; Cicero, L.; Preghenella, N. Sustainable organisational learning in sustainable companies. Learn. Organ. 2020, 28, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.Y.; Ebrahimi, B. A scalable method for identifying key indicators to assess urban environmental sustainability: A case study in Norway. City Environ. Interact. 2024, 22, 100144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J. Towards the Sustainable Corporation: Win-Win-Win Business Strategies for Sustainable Development. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1994, 36, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabbera, S.; Tibaingana, A.; Kiwala, Y.; Mugarura, J.T. Triple bottom line practices and the growth agro-processing enterprises in Uganda. Clean. Circ. Bioeconomy 2024, 8, 100081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosgaard, M.A.; Kristensen, H.S. From certified environmental management to certified SDG management: New sustainability perceptions and practices. Sustain. Futures 2023, 6, 100144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelkareem, R.S.; Mady, K.; Lebda, S.E.; Elmantawy, E.S. The effect of green competencies and values on carbon footprint on sustainable performance in healthcare sector. Clean. Responsible Consum. 2024, 12, 100179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, P.; Silva, S.C.; Roza, A.S.; Dias, J.C. Enhancing consumer purchase intentions for sustainable packaging products: An in-depth analysis of key determinants and strategic insights. Sustain. Futures 2024, 7, 100193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.U.; Saqib, A.; Abbasi, M.A.; Mikhaylov, A.; Pinter, G. Green Leadership, environmental knowledge Sharing, and sustainable performance in manufacturing Industry: Application from upper echelon theory. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2023, 60, 103540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Guan, X.; Wang, Z.; Qin, T.; Sun, R.; Wang, Y. Optimizing green supply chain circular economy in smart cities with integrated machine learning technology. Heliyon 2024, 10, 29825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deste, M.; Yıldırım, T.; Yurttaş, A. Analysis of the studies made in the field of green supply chain management by bibliometric method. Green Technol. Sustain. 2024, 2, 100062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özaşkın, A.; Görener, A. An integrated multi-criteria decision-making approach for overcoming barriers to green supply chain management and prioritizing alternative solutions. Supply Chain. Anal. 2023, 3, 100027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apeji, U.D.; Sunmola, F.T. Principles and Factors Influencing Visibility in Sustainable Supply Chains. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2022, 200, 1516–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okonta, D.E. Investigating the impact of building materials on energy efficiency and indoor cooling in Nigerian homes. Heliyon 2023, 9, 20316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carissimi, M.C.; Creazza, A.; Colicchia, C. Crossing the chasm: Investigating the relationship between sustainability and resilience in supply chain management. Clean. Logist. Supply Chain. 2023, 7, 100098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opoku, R.K.; Nyamah, E.Y.; Nyamah, E.Y.; Agyapong, G.; Frimpong, S.E. Sustainable manufacturing practices and sustainable performance: Evidence from Ghana’s food manufacturing sector. Clean. Logist. Supply Chain. 2023, 9, 100120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osei, M.B.; Papadopoulos, T.; Acquaye, A.; Stamati, T. Improving sustainable supply chain performance through organisational culture: A competing values framework approach. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2023, 29, 100821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seuring, S.; Aman, S.; Hettiarachchi, B.D.; Lima, F.A.; Schilling, L.; Sudusinghe, J.I. Reflecting on theory development in sustainable supply chain management. Clean. Logist. Supply Chain. 2022, 3, 100016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warasthe, R.; Brandenburg, M.; Seuring, S. Sustainability, risk and performance in textile and apparel supply chains. Clean. Logist. Supply Chain. 2022, 5, 100069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, H.N.; Ahmed, S.; Ahmed, T.; Taqi, H.M.M.; Ali, S.M. Disruptive supply chain technology assessment for sustainability journey: A framework of probabilistic group decision making. Heliyon 2024, 10, 25630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El jaouhari, A.; Arif, J.; Samadhiya, A.; Kumar, A. Net zero supply chain performance and industry 4.0 technologies: Past review and present introspective analysis for future research directions. Heliyon 2023, 9, e21525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asrol, M.; Marimin, M.; Yani, M.; Rohayati. A multi-criteria model of supply chain sustainability assessment and improvement for sugarcane agroindustry. Heliyon 2024, 10, 28259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vishwakarma, A.; Dangayach, G.S.; Meena, M.L.; Gupta, S. Analysing barriers of sustainable supply chain in apparel & textile sector: A hybrid ISM-MICMAC and DEMATEL approach. Clean. Logist. Supply Chain. 2022, 5, 100073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torkayesh, A.E.; Hendiani, S.; Walther, G.; Venghaus, S. Fueling the future: Overcoming the barriers to market development of renewable fuels in Germany using a novel analytical approach. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2024, 316, 1012–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inês, A.; Diniz, A.; Moreira, A.C. A review of greenwashing and supply chain management: Challenges ahead. Clean. Environ. Syst. 2023, 11, 100136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, R.R.; Ravi, V. Analysis of barriers of sustainable supply chain management in electronics industry: An interpretive structural modelling approach. Clean. Responsible Consum. 2021, 3, 100026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, M.R.; Ghosh, S.K.; Alam, M.F.B.; Rahman, M.F. A fuzzy multi-criteria model with Pareto analysis for prioritizing sustainable supply chain barriers in the textile industry: Evidence from an emerging economy. Sustain. Oper. Comput. 2024, 5, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekaran, U.; Bougie, R. Research Methods For Business: A Skill Building Approach, 8th ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wahyuni, S.; Safira, A.; Pramesti, M. Investigating the impact of growth mindset on empowerment, life satisfaction and turn over intention: Comparison between Indonesia and Vietnam. Heliyon 2023, 9, 12741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Years of Experiences in Supply Chain Fields | Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|

| <3 years | 1 | 7% |

| 3–5 years | 1 | 7% |

| 5–10 years | 0 | 0% |

| >10 years | 12 | 86% |

| Total | 14 | 100% |

| Job Positions | ||

| CEO/Owner | 6 | 43% |

| Directors | 4 | 29% |

| Senior Managers/GM | 1 | 7% |

| Managers | 2 | 14% |

| Others (Board commissioner) | 1 | 7% |

| Total | 14 | 100% |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 3 | 21% |

| Male | 11 | 79% |

| Total | 14 | 100% |

| Industry | ||

| Logistic & Distribution | 10 | 71% |

| FMCG | 3 | 21% |

| Logistic Association | 1 | 7% |

| Total | 14 | 100% |

| Size of Employee Body | ||

| <100 | 2 | 14% |

| 100–500 | 1 | 7% |

| >500 | 11 | 79% |

| Total | 14 | 100% |

| Respondents | Green Supply Chain Definition |

|---|---|

| Respondent 1 | GSCM refers to the implementation of environmentally friendly and sustainable practices. It is derived from two words: “green”, which means environmentally friendly, and “sustainable”, which means sustainable at every stage of the supply chain process. The goal is to minimize negative impacts on the environment. GSCM is viewed from three aspects: environmental, social, and economic, which must be balanced in a sustainable supply chain. |

| Respondent 2 | It relates to recycling and its impact on the environment. However, the difference between a green supply chain and a sustainable supply chain is not well understood, as these terms are not commonly used in Indonesia today. |

| Respondent 6 | GSCM is a process where we use environmentally friendly inputs and transform these inputs into outputs that can be further modified and reused at the end of their life cycle, thus creating a sustainable supply chain. |

| Respondent 7 | GSCM focuses on the short term, while SSC (sustainable supply chain) addresses the long term. GSCM involves environmentally friendly activities and is one of the initiatives of sustainability activities. Sustainability encompasses various factors, including environmental, economic, social, political, and other factors. |

| Respondent 8 | GSCM is essentially an evolution of supply chain management, which theoretically represents the theories or methods used from upstream to downstream. “Green” in the supply chain means incorporating environmental elements into the supply chain process itself, such as being environmentally friendly. In terms of transportation, GSCM can be interpreted as using materials that can be recycled, such as the use of B35 fuel in ships. |

| Respondent 9 | GSCM is an operational supply chain that works to minimize environmental damage from operations occurring within the supply chain process itself. On the other hand, it not only aims to minimize damage to the environment but also strives to enhance customer value and profit, particularly in terms of the company’s bonus margin. |

| Respondent 10 | In warehouses, GSCM typically involves changing fuel from diesel to electricity to reduce pollution. |

| Respondent 11 | GSCM relates to energy efficiency and the use of environmentally friendly equipment. |

| Respondent 13 | GSCM is the supply chain that you create where you are minimizing negative damage for the environment and try to procure ethically. GSCM is more like a continuous improvement process and journey to work. |

| Respondent 14 | GSCM initially arose from concerns regarding climate change and global warming, which ultimately lead to environmental damage. From this issue, the government and companies developed a solution, namely GSCM, which pays more attention to environmental considerations. |

| Respondent | GSCM Implementation in Companies |

|---|---|

| Respondent 1 |

|

| Respondent 2 |

|

| Respondent 3 |

|

| Respondent 4 |

|

| Respondent 5 |

|

| Respondent 6 |

|

| Respondent 7 |

|

| Respondent 8 |

|

| Respondent 9 |

|

| Respondent 10 |

|

| Respondent 11 |

|

| Respondent 12 |

|

| Respondent 13 |

|

| Respondent 14 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dwidienawati, D.; Indrajaya, B.L.; Zanten, E.V. Factors Affecting the Implementation of Green Supply Chain in Companies in Indonesia: A Qualitative Study. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5349. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125349

Dwidienawati D, Indrajaya BL, Zanten EV. Factors Affecting the Implementation of Green Supply Chain in Companies in Indonesia: A Qualitative Study. Sustainability. 2025; 17(12):5349. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125349

Chicago/Turabian StyleDwidienawati, Diena, Bella Lorenza Indrajaya, and Erik Van Zanten. 2025. "Factors Affecting the Implementation of Green Supply Chain in Companies in Indonesia: A Qualitative Study" Sustainability 17, no. 12: 5349. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125349

APA StyleDwidienawati, D., Indrajaya, B. L., & Zanten, E. V. (2025). Factors Affecting the Implementation of Green Supply Chain in Companies in Indonesia: A Qualitative Study. Sustainability, 17(12), 5349. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125349