1. Introduction

Following the implementation of the 2030 Agenda and its 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), of the United Nations [

1], sustainability has become a key factor to be undertaken in any aspect or activity that takes place in our society, and the wine sector is not left out of it. This aspect should not only be undertaken by the public initiative [

2] but should be accompanied by awareness and support from the private sector [

2]. Gómez and Molina [

3] highlight how wine tourism in Spain has contributed to strengthening the brand equity of designations of origin, emphasizing its strategic role in product differentiation and positioning.

Initially, the concept of sustainability was linked exclusively to environmental concerns. However, with the passage of time, this was expanded and has been extended to two other dimensions that today go hand in hand with it, such as economic and social [

4].

Recent studies, such as [

5], have emphasized the transformative role of wine tourism in promoting sustainability and innovation within wineries. Their case study of Bodegas Franco-Españolas illustrates how wine tourism can act as a strategic tool not only for economic diversification but also for fostering social cohesion and environmental responsibility, reinforcing the need for a holistic approach to sustainability in the wine sector.

The case of Valdeorras, as explored in [

6], illustrates how the revival of the Godello grape variety has been driven by a unique synergy between tradition and innovation. This process, rooted in local knowledge and supported by institutional collaboration, highlights the potential of wine tourism as a tool for sustainable rural development and cultural preservation.

In this context, our research seeks to answer the following question: How do sustainability practices in wineries influence wine tourism and contribute to the circular economy in Galicia? This question guides the analysis of the interactions between sustainability, economic development, and tourism dynamics in the region.

This expansion of dimensions within the concept of sustainability has led to an increase in the complexity of determining the actions linked to it, as well as its measurement, mainly because 8 of the 17 SDGs include considerations of this new and broader concept. Several authors have already referred to this greater complexity in different studies [

7,

8], to which we must add the growing concern that goes hand in hand with climate change, in order to preserve current resources through an efficient and rational use of them so that they can be passed on to new generations [

9,

10,

11]. In this way, all business sectors, including the Spanish wine sector, have become aware and internalized in recent decades of the need to carry out actions related to environmental care, among which those related to the use of renewable energies or the generalization of the wide range of activities linked to recycling stand out clearly.

This set of three dimensions, interrelated within the concept of sustainability, implies that it has been expanded globally to include different actions that have an impact on the territories and the local population. A cohesion that will now pursue that sustainability, from the economic point of view, refers to the generation of wealth, through the implementation of activities that respect the environment, sustainability from the environmental dimension, which is distributed equitably within the territory in which it is generated and the local population, sustainability from the social dimension [

12,

13].

Thus, when speaking of sustainability in the world of tourism and therefore, in the world of wine tourism, we must indicate that it refers to the contribution to sustainable development made by the wine sector throughout the territory and its population, as indicated by the UNWTO [

14].

In Spain, the Sustainable Tourism Strategy of Spain 2030 indicates that principles such as socioeconomic growth, conservation of natural and cultural values, social benefit, participation and governance, permanent adaptation and leadership are to be followed in the development of tourism and wine tourism sustainability [

15,

16], where these last two aspects indicated could even add new dimensions to the concept of sustainability by expanding the previous three coexisting ones with that of the contribution to citizen participation in decision making affecting their territory and that of leadership and public participation.

Wine tourism linked to the wine sector is a topic that has been discussed for decades [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22] and that tourism and wine tourism have had environmental, social and economic consequences, positive or negative [

23] is undeniable. But also something that does not admit discussion is the fact that if we focus on wine tourism and sustainability, the former is linked to a primary sector product such as viticulture and winemaking, which leads us to affirm that few tourism sectors can be as linked to sustainability as wine tourism, where the changing conditions coupled with climate change make them areas where concern for the preservation and care of the natural resources they possess, vital for the population and the business fabric of their environment, is extreme [

24,

25]. Sustainability in wine tourism is both the means and the end of the same strategy [

26].

But it is at this point where a more local than global awareness of the union of sustainability and wine tourism should be taken [

27], with a clear focus on the concept of circular economy, understood as focused on three main principles, such as waste-free design (creating products that can be easily repaired, reused or recycled), the maintenance of products and materials in use and the regeneration of natural systems, giving back to nature more of what we take, such as using compost instead of chemical fertilizers, activities in the direction proposed by the concept of circular economy [

28].

And the fact is that, traditionally, there has always been an attempt to provide a global solution to the union of both when it is precisely the opposite, since it has been shown that it results in greater awareness within the wine sector to provide specific actions for each territory, because each area, its population and its history [

29], requires customization that increases the involvement of all the actors that act around wine tourism [

30,

31].

A triple analysis must be carried out when talking about wine tourism and sustainability, that of the wine tourist (demander of experiences) and his or her perception of both factors, that of the wine sector professional (provider of experiences), and that of the local population where the return of the wine tourism activity takes place, as it is not possible to use the same criteria for all the protagonists in this analysis. The link between sustainability and territorial development is a necessity [

32].

This point is analyzed by other authors [

33,

34] making it clear that, in terms of wine tourism and sustainability, it is necessary to cover economic, social and environmental aspects by improving and/or creating services in the area and quality infrastructure, enhancing cultural heritage, creating employment and double satisfaction, on the one hand, to tourists and, on the other, to local residents. All this with the protection of the natural resources of the territory.

The objective is that wine tourism can become a true backbone of the territory, highlighting for some authors [

35] the role that wineries can play in this regard, with an awareness that has been growing in recent years, for example, with the approval of the European Wine Tourism Charter, which recognizes the importance of linking and interacting with the territory and local culture, under the perspective of sustainability [

36]. Wine tourism allows linking all the natural, cultural and gastronomic heritage of a given territory, disseminating the local history and sustainable practices developed by wineries.

And it is here where we enter into the analysis of wine tourism in Galicia, where we find the particularities of its territory, its heritage (whether cultural, natural or gastronomic) [

37] that allow us to determine what type of activities could be carried out in the sector so that the return of the wealth generated would have an impact on the territory and the population and, therefore, increase the weight in the GDP of the economy of the community.

The UNWTO offers different measurement systems, including Measuring the Sustainability of Tourism (MSF), which considers the three dimensions of sustainability (environmental, economic and social). It considers aspects such as tourism supply, employment and good jobs, infrastructure, water use, renewable energies, waste management, protection of the environment and the biosphere, and links with culture and heritage, among others.

As for the scientific literature on Circular Economy, it has been increasing in recent years, especially after the passage of the COVID-19 pandemic, although previous studies have already started to focus on it [

38]. There are different approaches and treatments of how the Sustainability and Circular Economy should be intertwined as, while theoretical strategies refer to the economic system, practical strategies refer to the actions to be taken to implement a Circular Economy system [

39].

In this paper, we contrast these aspects and their relevance for the different actors in the case of Galicia, carrying out a series of satisfaction and activity surveys, weighting in them a series of items among all the protagonists of Galician wine tourism, such as the wine tourists themselves, the activity providers (mainly wineries) and the social environment, following the work done in other previous studies within the field of wine tourism [

40] that allowed presenting and proposing different indicators [

41], as well as work presented directly on the situation in Galicia in the context of the circular economy [

42,

43].

Based on this framework, we propose the following hypotheses:

H1: The circular economy in the Galician wine sector is reinforced by specific sustainability-oriented practices—particularly those related to the use of renewable energies and the development of sustainable tourism activities—which have a significant impact on local economic development and winery revenues.

H2: A high proportion of the wineries in Galicia implement sustainability-related activities; however, only certain types of these activities, namely renewable energy usage and sustainable tourism initiatives, are statistically associated with improved financial performance.

2. Materials and Methods

In this paper, we analyze the information obtained from surveys carried out to the different actors within the Galician wine tourism activity.

Our first survey was carried out among the 116 wineries present in the public portal

Enoturismo en Galicia (

https://www.enoturismoengalicia.com) in which we asked about the activities linked to Sustainability and Circular Economy they had carried out and if these had had an impact on their turnover and on the surrounding territory. We obtained 100 responses to our survey.

In the second survey, we requested information from the 14 establishments that offer accommodation on the aforementioned portal, from a museum that is affiliated to it and from two restaurants also on this portal. The information obtained was used to determine whether these companies carried out any type of activity related to Sustainability and the Circular Economy, as well as whether or not these types of activities, carried out by wineries in their immediate geographical environment, had contributed to improving their turnover.

Finally, our third and fourth surveys were aimed at obtaining information on the profiles of wine tourists, on the one hand, those who had already enjoyed activities in Galicia on some occasion and, on the other hand, wine tourists who had not carried out activities in Galicia but had done so in other communities in Spain or internationally. We thus obtained data on the main reasons that moved wine tourists to carry out their experiences, and what they demanded, also measuring the degree of satisfaction with which their expectations were met in the specific case of wine tourists in Galicia. This survey was conducted through the portal on sobrelias.com, a digital magazine linked to the wine sector that is more than 8 years old, using the program QSM Version (10.1.1).

With the data obtained from the first survey, an analysis of the relationship between sustainable activities and circular economy and the improvement of wineries’ income was carried out. We sought to identify whether the implementation of sustainable activities in companies is associated with improved income. To this end, we conducted a survey with 10 closed questions (“yes” or “no”) to a set of 116 wineries, obtaining 100 responses to the survey. Of these, 5 questions focused on sustainable activities and 1 question on revenue improvement. Chi-square tests and Phi coefficient calculations were performed to analyze associations.

The data from the second survey were used to analyze the positive and negative perception, as well as the proactive and collaborative attitude of these establishments to promote and participate in new activities related to sustainable wine tourism and circular economy. Seventeen surveys of 8 closed questions (“yes” or “no”) were carried out, obtaining 17 responses. Given the small number of the sample, we opted for a descriptive analysis, accompanied by a binomial model for some of the questions asked. With our sample size, the precision of the estimates was limited. The confidence intervals were wider than if our sample had been larger.

With the data from our third and fourth surveys, we analyzed the typical profile of wine tourists in Galicia and outside Galicia. In the third survey, we analyzed the experiences of wine tourists with experiences already completed in Galicia and we obtained 124 surveys. In the fourth survey, we obtained 264 surveys. In both surveys, we asked 12 questions, one of which was a sociodemographic control question (age range). One of the questions, referring to the origin/provenance of the wine tourist, had a dichotomous option, while the remaining 10 questions had different degrees of valuation. We performed two multivariate ANOVA analyses, one for wine tourists with experiences in Galicia and the other for those with experiences outside Galicia, to observe the variable “Level of satisfaction with the wine tourism experience” weighted by the factors “Cultural Heritage”, “Natural Heritage”, “Gastronomic Richness”, “Sustainable Wine Tourism” and “Adequate Infrastructure”. Finally, we carried out a descriptive analysis of those weighting factors that wine tourists with experiences in Galicia and outside Galicia take most into account, for which we have evaluated the responses obtained with values from 1 to 5.

3. Results

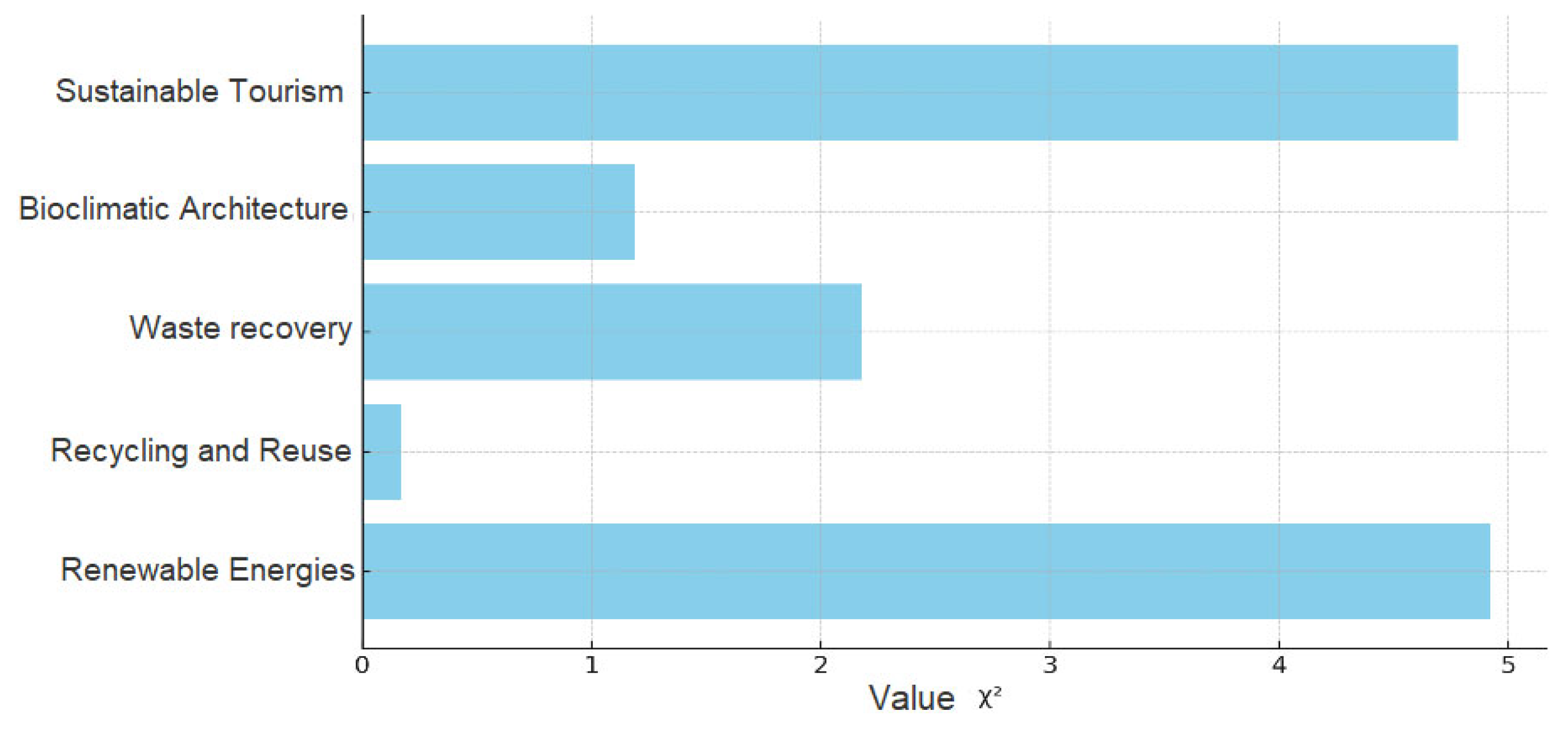

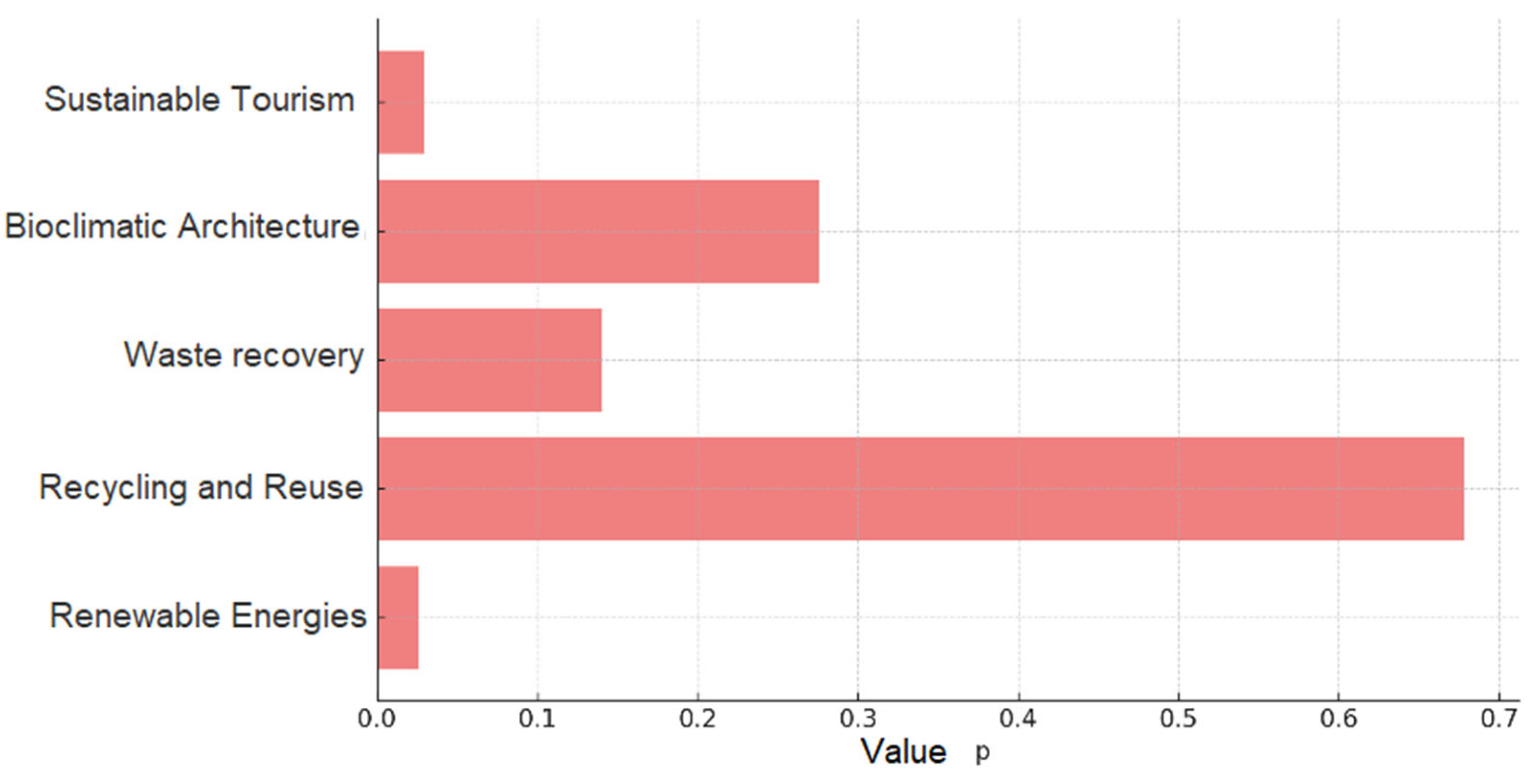

On the information obtained from the winery survey, we performed the Chi-square test for each activity (

Figure 1), calculated the

p-value for each activity (

Figure 2) and calculated the Phi Coefficient for the strength of the association (

Figure 3).

Figure 1 shows the chi-square values for each sustainable activity evaluated. As shown in

Figure 2, only renewable energy and sustainable tourism activities have

p-values below 0.05, indicating statistical significance.

The results indicate that the use of renewable energies and sustainable tourism activities are significantly associated with increased income. In contrast, recycling, waste utilization, and bioclimatic architecture do not show a significant association. The strengths of the associations (Phi) are moderate, around 0.15.

The survey of the companies linked to the portal (enoturismoengalicia.com) that are located in the geographical area of the wineries that carry out wine tourism activities provided us with information for a descriptive analysis.

Table 2 summarizes the descriptive statistics of responses from businesses located near wineries engaged in sustainable wine tourism. The table below (

Table 2) shows two key values of analysis for each item, namely the mean and the standard deviation, where the latter indicated how much the responses vary around the former. A low value means that the responses are very similar to each other, while a high value means that there is more variety in the responses.

75% of those surveyed carry out sustainable wine tourism and circular economy activities. There is some variability in the answers to which we can add that 100% of the respondents answered that there are wineries in their area that carry out these activities. There is no variability, which has led to the fact that 93.75% of respondents have seen an increase in their turnover thanks to these activities. There is very little variability.

This has motivated 87.5% of the respondents to collaborate directly with the wineries. There is little variability as 100% believe that these activities would increase the wealth of the area and 81.25% believe that these activities help people to stay in rural areas. All this means that 93.75% of those surveyed would propose and promote these activities.

Where there is a greater range of responses is in whether they consider that the public authorities are carrying out joint or promotional work for this type of sustainability and circular economy activities, since there, the percentage of respondents indicating that public participation (support) is the correct one is 68.75% (

Figure 4).

Figure 4 illustrates the percentage of positive responses to each survey item. The summary of our descriptive analysis indicates that, in general, respondents have a very positive view of sustainable wine tourism and circular economy activities. Most believe that they would increase their income, benefit the local economy and help maintain population in rural areas. However, there is a little more disagreement regarding public support, not considering that it is sometimes sufficient.

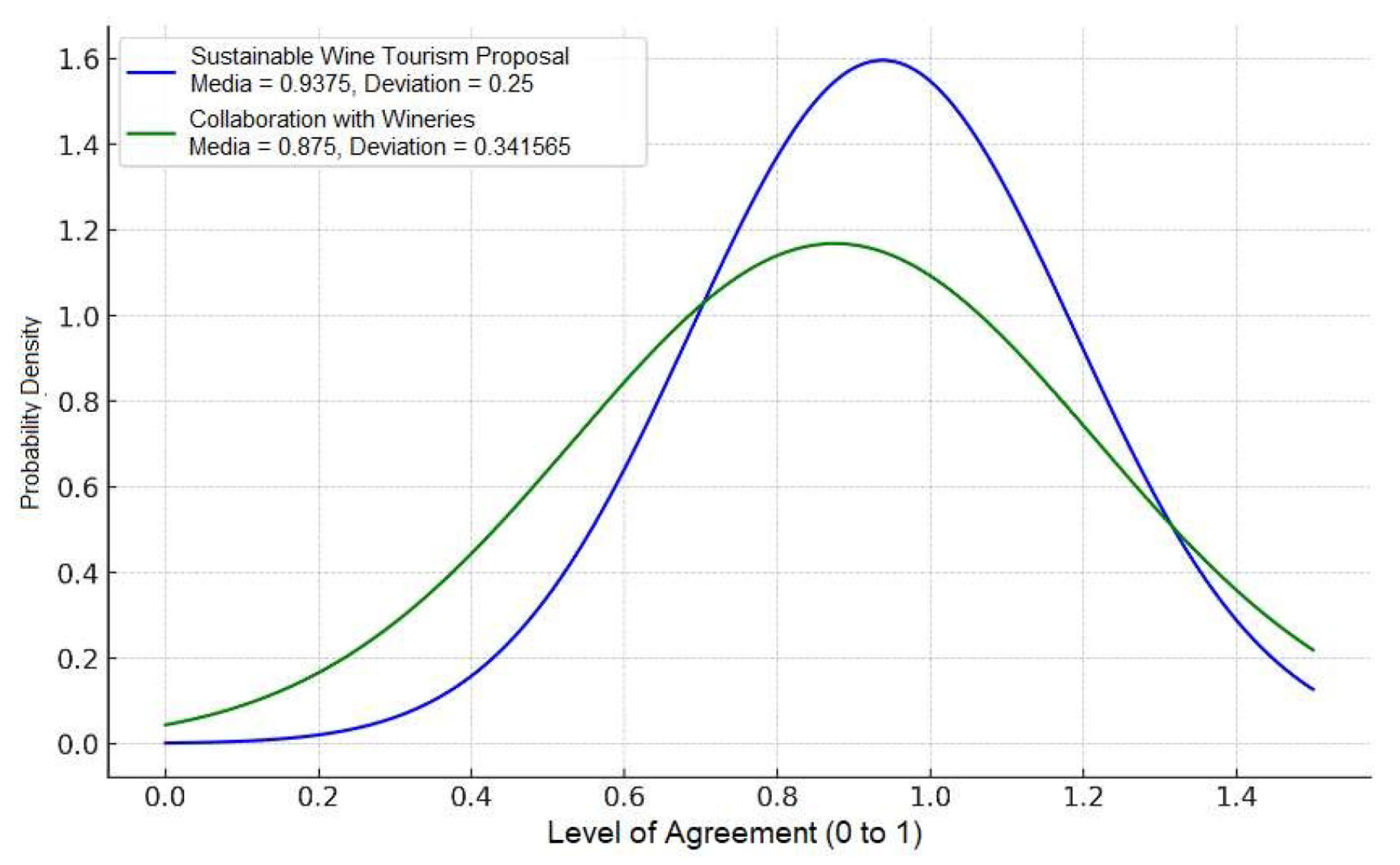

3.1. Binomial Model for Two Items (Figure 5)

Figure 5 illustrates the binomial distribution of responses regarding collaboration and promotion of sustainable wine tourism. The mean (μ) for the question “Would you propose and promote sustainable wine tourism activities?” is 0.9375, indicating that nearly 94% of respondents agree with the proposition. This high rating is very positive. The standard deviation (σ) is 0.25, suggesting that most responses are close to the mean, with minimal variability. This indicates strong overall support for promoting sustainable wine tourism activities, reflecting a generally positive acceptance of the idea.

Figure 5.

Binomial analysis of willingness to propose and current collaboration in sustainable wine tourism.

Figure 5.

Binomial analysis of willingness to propose and current collaboration in sustainable wine tourism.

For the question “Do you collaborate directly with the wineries in your area to carry out activities related to sustainable wine tourism and circular economy together?”, the mean (μ) is 0.875, showing that 87.5% of respondents actively collaborate with local wineries. The standard deviation (σ) is 0.341565, indicating some variability in responses. While most respondents collaborate with wineries, a few show some reluctance.

These results suggest a high level of collaboration between different actors within the same territory regarding sustainable wine tourism and circular economy activities. However, not all non-winery participants are equally engaged.

It suggests that the level of collaboration between the different actors within the same territory in terms of sustainable wine tourism and circular economy is high, but not for all of the non-winery participants.

To conclude the analysis of our work, we conducted two surveys. The first one determined the typical profile of the wine tourists who have already carried out some type of activity in Galicia. The second showed the typical profile of wine tourists with experiences not carried out in the Galician community. We analyzed geographical areas of origin, average time and average expenditure of the typical wine tourist, degree of satisfaction with the experience based on different factors linked to the circular economy such as natural heritage, cultural heritage, gastronomic offer or the realization of activities linked to sustainable wine tourism. We made a comparison of both profiles that showed differences and similarities, allowing the determination of those aspects that represented advantages to be the destination of preference.

3.2. Multivariate ANOVA Analysis: Multiple Linear Regression

As a variable to be weighted we have determined the “Degree of satisfaction with the wine tourism experience”, being the factors to be measured that have a possible influence on it the variables “Cultural Heritage”, “Natural Heritage”, “Gastronomic Richness”, “Sustainable Wine Tourism” and “Infrastructures and Means of Transportation”.

The initial equation is as follows:

where

Ŷ: Degree of satisfaction with the wine tourism experience;

K: Constant;

a, b, c, d, e: Parameters;

X1: Cultural Heritage Relevance;

X2: Relevance of Natural Heritage;

X3: Relevance of Gastronomic Wealth;

X4: Relevance of Sustainable Enotourism activities;

X5: Relevance of the correct Infrastructure and Means of Transportation.

This model allows us to assess the relative influence of each factor on the overall satisfaction of wine tourists.

3.3. Experienced Wine Tourists in Galicia

The analysis of wine tourists who have experienced wine tourism in Galicia reveals several key insights. The multiple correlation coefficient (R) is 0.941937, indicating a strong relationship between the factors considered and the degree of satisfaction. The coefficient of determination (R2) is 0.887245, suggesting that approximately 88.72% of the variability in satisfaction can be explained by the factors analyzed.

The intercept value of 1.33 is statistically significant, indicating that even when all factors are zero, the average satisfaction is positive. The analysis shows that Cultural Heritage has a negligible impact on satisfaction, with a coefficient of −0.00284 and a p-value of 0.9665, indicating it is not statistically significant. Natural Heritage also has a slight negative relationship with satisfaction, with a coefficient of −0.06758 and a p-value of 0.3265, which is not statistically significant.

Conversely, Gastronomic Richness has a strong positive impact on satisfaction, with a coefficient of 0.52976 and a highly significant

p-value of 3.16 × 10

−16. Sustainable Wine Tourism has a slight positive impact, with a coefficient of 0.04491 and a

p-value of 0.5097, indicating it is not statistically significant. Infrastructure and Means of Transportation have a moderate positive influence on satisfaction, with a coefficient of 0.24341 and a significant

p-value of 0.00032. The results of the regression analysis are summarized in

Table 3. The regression equation obtained was as follows (

Table 3):

3.4. Wine Tourists with Experiences Outside Galicia

The analysis of wine tourists who have experienced wine tourism outside Galicia shows different results. The multiple correlation coefficient (R) is 0.902142, indicating a strong relationship between the factors considered and the degree of satisfaction. The coefficient of determination (R2) is 0.813861, suggesting that approximately 81.39% of the variability in satisfaction can be explained by the factors analyzed.

The intercept value of 1.2493 is statistically significant, indicating that even when all factors are zero, the average satisfaction is positive. Cultural Heritage has a negligible impact on satisfaction, with a coefficient of −0.00586 and a p-value of 0.926, indicating it is not statistically significant. Natural Heritage has a notable positive impact on satisfaction, with a coefficient of 0.5132 and a highly significant p-value of 2.78 × 10−12.

Gastronomic Wealth also has a strong positive impact on satisfaction, with a coefficient of 0.5175 and a highly significant

p-value of 1.44 × 10

−12. Sustainable Wine Tourism has a slight positive impact, with a coefficient of 0.08628 and a

p-value of 0.202, indicating it is not statistically significant. Infrastructure and Means of Transportation have a moderate negative impact on satisfaction, with a coefficient of −0.3148 and a significant

p-value of 0.00014.

Table 4 presents the regression results for wine tourists with experiences outside Galicia. The regression equation obtained was as follows (

Table 4):

3.5. Descriptive Analysis of Wine Tourists’ Profiles

The profile of the wine tourists who carry out activities in Galician wineries is mostly from within the community (80.65%). On the other hand, 64.02% of wine tourists in other areas of Spain are from the community in which they carry out their activity.

Wine tourists in Galicia are between 36 and 55 years of age (48.39%) and carry out their activity as a couple (38.70%). In other areas of Spain, the majority of wine tourists are also between 36 and 55 years of age (56.06%), but they prefer to spend their time with their families (32.20%).

The wine tourist in Galicia mainly carries out his activity in one day, 75%, compared to the wine tourist in other areas, who represents 64.39%. This difference also occurs in those profiles that carry out their experience for two days, being 16.13% in Galicia and 24.62% in other areas of the country.

As for the expenditure per visitor per day, in Galicia 83.08% is below €50 and in the rest of the country it is 76.51%. In the range between €50 and €100, wine tourists in Galicia account for 12.09% compared to 17.04% in the rest of the country.

The degree of satisfaction with their experience in Galicia is “completely satisfied” 52.42% compared to 51.51% in other areas, “very satisfied” 38.71% in Galicia compared to 35.95% in other areas and “satisfied” 6.55% in Galicia compared to 7.58% in other areas. Wine tourists who carry out their activity in Galicia show a higher percentage of satisfaction than those in other areas.

In addition, if they would repeat the experience in Galicia “completely” 32.26%, “very probably” 33.87%, “probably” 29.03%, “unlikely” 4.03% and “not at all likely” 0.81%. Differences are shown with respect to wine tourists from other areas who would repeat destination “completely” 30.30%, “very probably” 35.98%, “probably” 25.75%, “not very likely” 4.54% and “not at all likely” 3.43%. Wine tourists in Galicia are more likely to repeat the experience. These results highlight the differences in tourist behavior and satisfaction between Galicia and other regions.

3.6. Weighting and Relevance Factors

We want to analyze whether there are significant differences in the average scores of the different aspects evaluated (cultural heritage, natural heritage, gastronomic richness, sustainable wine tourism and infrastructure and means of transport) between the two groups of wine tourists.

Figure 6 indicate factors valued by wine tourists in their experiences.

Figure 7 compares the average scores of key factors between tourists in Galicia and those in other regions. The average values obtained are shown in

Table 5 below.

The analysis of the data obtained in the surveys indicated that wine tourists who have had wine tourism experiences in Galicia rate them better than those who have had them in other places (not Galicia) supported by the Natural Heritage factor and by Gastronomic Richness (3.9 vs. 3.74 and 4.28 vs. 4.13, respectively), on a scale of 1 to 5.

It also showed that the factors Cultural Heritage, Sustainable Wine Tourism, and Infrastructures and Means of Transport, are factors more valued by wine tourists who carry out their experiences outside Galicia compared to those who have carried them out in this community (3.41 vs. 3.34, 3.42 vs. 3.25 and 3.92 vs. 3.72, respectively), on a scale of 1 to 5.

These findings enable us to reconsider the two initial hypotheses proposed in this study.

Regarding H1, the statistical analysis confirms that specific sustainability practices—namely, the use of renewable energy and sustainable tourism—are significantly associated with higher revenues in Galician wineries (p-values of 0.026 and 0.029, respectively). These results validate the idea that not all sustainability practices contribute equally to the circular economy, but rather that targeted efforts in energy and tourism are particularly impactful.

With respect to H2, the survey data show that, although the majority of wineries report undertaking sustainability-related activities, only a subset of these practices (namely the aforementioned ones) correlate significantly with improved income. Therefore, the hypothesis must be nuanced: while sustainability is widely implemented, its economic effectiveness depends on the type of action undertaken.

5. Conclusions

The first conclusion we obtained is that wine tourists who have carried out their wine tourism experiences in areas that do not belong to Galicia, valued more factors such as Cultural Heritage, Sustainable Wine Tourism activities and Infrastructure and means of transport. Meanwhile, the enotourists who carried out their enotourism experiences in Galicia, valued its Natural Heritage and its Gastronomic Wealth more.

The factor with the highest weighting in terms of the difference in both surveys is the factor Infrastructure and means of transport, with a weighting difference of 0.20 in favor of experiences outside Galicia. This is a community located at the extreme end of the peninsula, quite distant geographically from other areas of the country, very conditioned by the orography, linked to small vineyards (smallholdings) that force wine tourists to spend a lot of time getting from their origin to Galicia and, within this community, to make transfers to other parts of the country through infrastructures that are not equipped like those in other areas of the country, with no alternative means of transport, having to use their own vehicle to reach the final destination of the chosen wine tourism experience. Deficient infrastructures, lack of alternative means of transport and wine tourism areas that are difficult to access, make this a negative factor for wine tourists in Galicia compared to those in other areas. It is concluded that wine tourists want to enjoy their experience without having to waste too much time getting to the location, which is a negative handicap in this community.

In summary, this study highlights the importance of sustainability practices in wineries as a driver of wine tourism development and their contribution to the circular economy in Galicia. The findings demonstrate that while natural heritage and gastronomy are key strengths of the region, there is significant room for improvement in infrastructure and the implementation of sustainable wine tourism activities.

From a theoretical perspective, this research contributes to the growing body of literature on sustainable tourism and circular economy by providing empirical evidence from a regional case study. It reinforces the idea that sustainability in wine tourism must be approached holistically, considering environmental, economic, and social dimensions.

From a managerial standpoint, the results suggest that wineries and tourism stakeholders in Galicia should invest in improving accessibility and diversifying sustainable tourism offerings. Strengthening collaboration among wineries, local businesses, and public institutions is essential to enhance the visitor experience and maximize the socio-economic benefits for rural communities.

This study is not without limitations. The sample size for non-winery stakeholders was relatively small, which may affect the generalizability of the findings. Additionally, the study focused on a single region, which limits the ability to compare across different wine tourism destinations.

Future research should aim to expand the sample to include a broader range of stakeholders and explore longitudinal data to assess the long-term impact of sustainability practices. Comparative studies between regions could also provide deeper insights into best practices and scalable strategies for sustainable wine tourism.

6. Limitations and Future Studies

In this study, we have been limited in the number of surveys we have been able to carry out with the actors indirectly linked to wine tourism activities, those companies that collaborate, although they are not the ones that carry them out, in their implementation and realization.

Additionally, the study is geographically limited to the region of Galicia, which may restrict the generalizability of the findings to other wine tourism destinations with different socio-economic, cultural, or environmental contexts. The cross-sectional nature of the data also limits the ability to assess long-term impacts of sustainability practices on wine tourism and the circular economy.

Another limitation lies in the reliance on self-reported data, which may be subject to response bias or social desirability effects, particularly in questions related to sustainability. Furthermore, the relatively small sample size of non-winery stakeholders (e.g., accommodation providers, restaurants, and cultural institutions) reduces the statistical power of the analysis and may not fully capture the diversity of perspectives within the sector.

In a future study we will analyze this fundamental part of wine tourism in more depth, since it is, after all, one of the fundamental actors that can benefit the most from Sustainability and the Circular Economy.

Future research should consider longitudinal designs to track the evolution of sustainability practices over time and their cumulative effects. Expanding the scope to include comparative studies across different wine regions could also provide valuable insights into best practices and scalable models for sustainable wine tourism.

_Li.png)