Place-Based Impact: Accelerating Agri-Technology Adoption in an Evolving ‘Place’

Abstract

1. Introduction

“those dimensions of self that define the individual’s personal identity in relation to the physical environment by means of a complex pattern of conscious and unconscious ideas, feelings, values, goals, preferences, skills, and behavioral tendencies relevant to a specific environment”.

“characterized by ideologies of state interventionism, liberal democracy, redistribution, and equal development, [so] reforms at the level of planning legislation and administration, as well as structural reforms of local and regional government, [have] led to the founding of national spatial planning systems. Influenced by positivist spatial planning perspectives… territorial reconfigurations based on sharp administrative divisions (counties and municipalities), a hierarchical positioning of cities and towns, and a continuity of access to public and private services throughout national territories [have taken place] which would have otherwise remained concentrated in just a few urban areas”.([20] p. 3)

“The Government is today (Friday 31 January 2025) launching a consultation on a new strategic approach to managing land use in England to give decision makers the data they need to protect our most productive agricultural land, boosting Britain’s food security in a time of global uncertainty and a changing climate. This will support the Government’s missions under the Plan for Change, including delivering new housebuilding, energy infrastructure and new towns (https://www.gov.uk/government/news/government-launches-national-conversation-on-land-use accessed on 2 March 2025).”

“This Government has a cast-iron commitment to maintain long-term food production. The primary purpose of farming will always be to produce food that feeds the nation. This framework will give decision makers the toolkit they need to protect our highest quality agricultural land. This vision for land is one in which we guarantee our long-term food security and future-proof our farm businesses, support new housebuilding and energy infrastructure, and reduce conflicts that hold up development by creating land with multiple benefits—supporting economic growth on the limited land we have available. The Framework will help farm businesses to maximize the potential of multiple uses of land, supporting long-term food production capacity and unlocking opportunities for businesses to drive private finance into the sector. It will support the need to incentivize multi-functional land use that includes food production…”

“From a planning perspective, we may thus distinguish between implicit and explicit spatial consciousness, as well as strongly or weakly articulated spatial consciousness… Based on forms of individual or collective awareness of one’s own spatial presence, as individual or community, and of real-world spatial phenomena and processes, explicit spatial consciousness may provide the intellectual means to bridge the gap between spatial and aspatial dimensions of social processes, governance, and participation”.

“a strong and taken for granted bond, prevalent among people who have spent their whole life in one place, who have strong family connections in it and who cannot imagine leaving”.([26] p. 71)

2. Conceptual Approach

- Detailed exploration of a real-world context—using qualitative and quantitative data and studies to explore a given case in order to examine real situations rather than theoretical conjecture (the “what, where, when and who”);

- Causal and contributory factors and framings—considering causal and contributory factors and framings that inform certain outcomes (the “how and why”);

- Conceptual development—using existing concepts and theories to generate new insights (the “what, and what ifs”).

3. Theoretical Framing of Place, Space, and Place-Related Policy

- Assets in place include natural assets and resources, heritage and natural vistas, knowledge and climatic environment;

- Services encompass health, education, employment opportunities, justice, welfare and government support of communities, in terms of not only provision but also accessibility especially in rural areas;

- Governance embraces the processes and activities that support the communities to thrive or conversely fail to thrive;

- Identities reflect who we think we are and what we believe the place to be [44].

“place-making becomes a mask for the displacement of those incumbent low-income people seen as transgressive and undesirable, and for their replacement with a better-resourced and presumably better-behaved population in an envisioned, desired future”.

| Factor | Description | Ethical Perspectives |

|---|---|---|

| Centralized and remote policy making | Bureaucratic nature of government focuses on delivering broad, desirable objectives with less regard for localized desirable and undesirable outcomes. This can be described as national spatial development strategies such as in the draft UK Planning and Infrastructure Bill. | A utilitarian perspective arises from the adoption of spatial development strategies as the policy is designed to enable the greater good for the country or the region rather than win–win outcomes which recognize place. |

| Confusion between policies being location-sensitive and place-based | Whilst place-based policies reflect the heritage of values, aspirations, and identities of a place, location-sensitive policies reflect the needs of a location at a specific point in time. | A relativism perspective arises here. Place-based policies reflect cultural norms rather than applying general rules to all contexts. Location-sensitive policies reflect specific rules that can be applied to deliver specific objectives and meet specific needs. What is right and appropriate is relative to each type of policy. |

| Definitional obscurity | Where plans and specifications are obscure with different potential interpretations, or hidden meanings, this will impact on the effectiveness of their implementation and the level of ambiguity within associated narratives on what is intended in terms of objectives and outcomes. | Definitional obscurity will drive a different perspective in addressing a given issue promoting a relativist perspective. Different actors will have different perceptions of what is a good or bad intention or outcome based on their cultural norms and standards and viewpoints especially those who have a positivist viewpoint and those who have an interpretivist viewpoint. |

| Economic restructuring | Economic restructuring driven by technology adoption often results in labor displacement and shifts toward services or amenities that may not align with existing perceptions and identities of place. This can promote place-making based on future potential or place-masking, which overlooks existing place identities. | A utilitarian perspective arises where policy enables the greater good rather than win–win outcomes. The driver for economic restructuring, national and/or regional spatial development plans, and market level drivers for economic restructuring may limit the integration of place-making or even promote place-masking. |

| Policy where the individual and the greater good are explicitly in conflict | Policy can be in explicit conflict when the rights of the individual, commitment to private property ownership because they are pitched against collective benefits such as delivering policy agendas such the development and deployment of spatial development plans addressing The Methane Pledge, biodiversity (30 by 30) in the UK or national net zero emissions targets. | A utilitarian perspective arises where policy enables the greater good rather than win–win outcomes. Power dynamics and imbalances will influence who wins and who loses in these scenarios. |

| Sectoral organization of government | Institutional separation in the government of economic concerns (treasury) and a wider range of social concerns (employment, welfare, health, education, justice), make it difficult to recognize and act where competing governmental interests either converge or are in conflict. | Ethical egoism holds that moral norms serve the function of promoting the self-interest of a particular individual or agent. Self-interest can converge between agents or be in conflict. |

| Stakeholder communication and trust deficits | Lack of effective communication between local stakeholders (e.g., farmers, communities, policymakers) can lead to tensions, especially when individual decisions—such as adopting financially incentivized land uses like solar panels—conflict with community perceptions, expectations, or long-term visions for place. | A relational ethics perspective applies, emphasizing the need for dialogue, trust, and mutual understanding to balance individual choices with collective well-being. |

| Project/Site | Description | Nature of Conflict | Stakeholders Involved | Outcome/Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bicathorpe Oil Drilling [56] | Oil drilling plans in the Lincolnshire Wolds, an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB) | Legal challenges due to environmental impacts and protected landscape status. | Local councils, environmental groups (SOS Biscathorpe), Planning Inspectorate. | High Court legal proceedings ongoing. |

| Gate Burton Energy Park [57] | Proposed large-scale solar farm in Lincolnshire. | Delays due to archaeological assessments, tensions between renewable energy goals and heritage preservation. | Developers, local authorities, archaeologists, local communities. | Project delayed by over six months, incurring an additional £1 million in costs. |

| Nocton Dairies ‘Super Dairy’ [58] | Proposal for intensive dairy operation housing up to 8100 cows. | Public opposition due to environmental concerns, animal welfare, and local community impact. | Nocton Dairies, Environment Agency, local residents, North Kesteven District Council. | Application withdrawn after extensive opposition and regulatory concerns. |

| Winterton Solar Farm [59] | 10 MW solar farm planned on agricultural land. | Conflict over landscape, biodiversity, renewable energy versus agricultural land preservation. | North Lincolnshire Council, developers, local residents. | Planning permission granted on appeal with mitigation conditions. |

- Self-identity aspects (attitude, feelings and behavior) such as the effects of digitalization on farmer identity, farmer skills, and farm work;

- Institutional shape (see Table 1) namely power, ownership, privacy and ethics in digitalizing agricultural production systems and value chains and also economics and management of digitalized agricultural production systems and value chains and digitalization and agricultural knowledge and innovation systems (AKIS);

- Physical shape, i.e., the contextual geography of adoption, uses and adaptation of digital technologies on farm.

- The influence of transition on self-esteem and well-being when self-identity is reframed to a new status that the individual (and wider community) does not identify with, and the place no longer provides a positive reinforcement of identity or values.

- The interaction between self-efficacy and place attachment, especially place dependence, and the ability of the individual (and wider community) to cope when the landscape and the practices within that landscape are stigmatized to drive policy change or are culturally stigmatized in the name of economic development [13], or to address nature recovery or the mitigation of pollution risk from agriculture [62]. The stigma can also extend to the derived products such as meat or milk when agricultural practices and the associated products, which are described as damaging in terms of greenhouse gas emissions versus plant-based alternatives.

- The continuity of self in relation to place-identity where changes to landscape are associated with grief or loss, i.e., land that has been in the possession of families for generations can be lost and also carry a stigma of something that is no longer pure or natural… where this bond between a person and land increases with age, it will become more difficult for new meanings to be given to communities if “the population is older and more rooted [in the place] as compared to an area with high mobility and a lower average age” [4] (p. 113).

- The loss of distinctiveness. Locations can have a heritage of particular breeds of livestock or crops (in the case of Lincolnshire, Lincoln Red cattle or Lincoln Longwool sheep), and a transition to types of agriculture where this distinctiveness is lost impact on perceptions of this new place.

4. Lincolnshire: Findings from an Explanatory Case Study

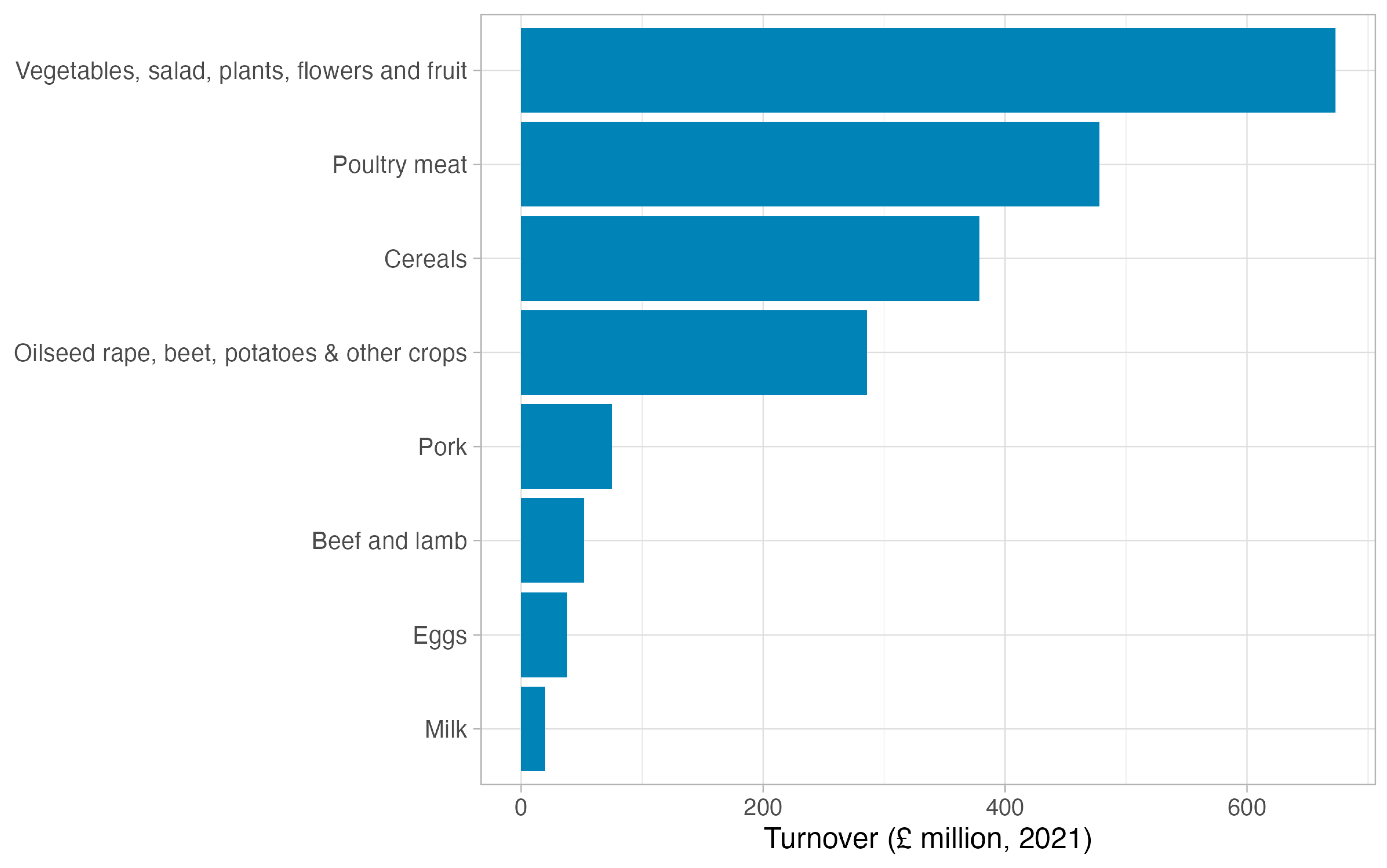

“The UK Food Valley food chain had average annual output over the period 2019–2021 estimated at: £10.7 billion of turnover in agriculture and food processing and distribution, generating a contribution to the economy of £4 billion; £3.9 billion of turnover in food retail and catering, generating £1.1 billion for the economy; to give a total food chain with sales of £14.6 billion and contributing £5.1 billion to the economy”.[66]

4.1. Causal and Contributory Factors and Framings—Considering Causal and Contributory Factors and Framings That Inform Certain Outcomes (The How and Why)

“Specialized farmers delegate product marketing and the purchase of inputs to centralized agencies and concentrate their efforts solely on production activities… regions can only remain competitive if marketing and logistics are highly centralized, as this is the only way that production can meet the requirements of the centralized purchase platforms of large scale retailers”.

“The Planning and Infrastructure Bill is central to the government’s plan to get Britain building again and deliver economic growth. The Bill will speed up and streamline the delivery of new homes and critical infrastructure, supporting delivery of the government’s Plan for Change milestones of building 1.5 million safe and decent homes in England and fast-tracking 150 planning decisions on major economic infrastructure projects by the end of this Parliament. It will also support delivery of the government’s Clean Power 2030 target by ensuring that key clean energy projects are built as quickly as possible”.[70]

- Delivering a faster and more certain consenting process for critical infrastructure by “upgrading the country’s major economic infrastructure—including our electricity networks and clean energy sources, roads, public transport links and water supplies—is essential to delivering basic services and growing the economy”;

- Introducing a more strategic approach to nature recovery with introducing a new Nature Restoration Fund that “will unlock and accelerate development while going beyond simply offsetting harm to unlock the positive impact development can have in driving nature recovery”;

- Improving certainty and decision making in the planning system, where local communities shape decisions but that planning committees can still operate as effectively as possible so “the Bill will ensure that they play their proper role in scrutinizing development without obstructing it, whilst maximizing the use of experienced professional planners”.

- Unlocking land and securing public value for large-scale investment “to unlock more sites for development, the Bill will ensure that compensation paid to landowners through the compulsory purchase order process is fair but not excessive, and that development corporations can operate effectively”.

- Introducing effective new mechanisms for cross-boundary strategic planning “to develop strategic planning with effective cross-boundary working to address development and infrastructure needs”.

“It allows Natural England (or another designated delivery body) to bring forward Environmental Delivery Plans (EDPs), that will set out the strategic action to be taken to address the impact that development has on a protected site or species and, crucially, how these actions go further than the current approach and support nature recovery. Where an EDP is in place [developed by experts in Natural England] and a developer utilizes it, the developer would no longer be required to undertake their own assessments, or deliver project-specific interventions, for issues addressed by the EDP…. The budget allocated £14 million for the Nature Restoration Fund in the next financial year, but its steady state operation will be on a full cost recovery basis”.[72]

“Natural England may acquire land compulsorily if the Secretary of State authorizes it to do so. The power … may be exercised in relation to land only if Natural England requires the land for purposes connected with the taking of a conservation measure”.

4.2. Conceptual Development—Using Existing Concepts and Theories to Generate New Insights (The What, and What Ifs)

- Sustained political will from political system to public support;

- Interagency co-ordination between national agencies and all levels of government;

- Capacity of national systems—strong institutional capacity (technical, human and financial);

- International and regional cooperation—collaboration with and support for international and regional partners and networks;

- Sustained financing—adequate, sustained and planned financing from a range of sources [75].

“the deep structure that accounts for the stability of an existing socio-technical system. It refers to the semi-coherent set of rules that orient and coordinate the activities of the social groups that reproduce the various elements of socio-technical systems”.

| System Level | Description | Drivers | Outputs | Agri-Technology Related Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1—Supranational bodies and associations | International geopolitical, environmental, and economic systems, influencing national policies and market conditions | Geo-political climate International non-governmental bodies Transnational corporations | Intergovernmental agreements International standards and codes of practice Pledges/commitments Policies | The Methane Pledge Sustainable Development Goals International Biodiversity Agreements |

| 2—Government (policy and budgeting) | National and regional governments setting laws, policies, and financial priorities | Political climate Public awareness Public finances Public opinion | Government spending plans Laws/legislation policy | 30 by 30 (biodiversity strategy) Planning and Infrastructure Bill |

| 3—Regulatory bodies and associations | Institutions translating legislation into enforceable regulations, standards, and rules | Legislation and intergovernmental agreements and commitments need to be converted into market-based rules and/or regulations | Judgments Laws Standards | Environmentally permitting for agri-technology Permitting and regulation for use of agri-technology in public spaces (e.g., autonomous machinery on public footpaths) Animal welfare standards GHG emissions regulations |

| 4—Local government (policy and budgeting) | Local authorities responsible for implementing national policies and addressing place-based needs | Local governance priorities Community engagement Budget constraints | Local planning decisions Infrastructure support Community initiatives | Local zoning for agri-technology facilities Support for local food hubs Funding for agri-technology training and educational programs at local educational institutions |

| 5—Organizations (companies and households) | Businesses, farms, cooperatives, and households making operational and investment decisions in response to market and regulatory conditions | Changing market conditions Changing regulatory conditions External company/household pressures Internal company/household pressures | Technology adoption Investment decisions Supply chain adjustments | Adoption of precision agriculture technology Adoption of solar panels on farmland Big data leveraged to inform decision making |

| 6—Technical and operational management | Day-to-day decision making and practices in farms, agribusinesses, and related operations | Technical feasibility Resource availability Skill levels | Implementation of technology Operational efficiency Environmental management | Use of AI-based crop monitoring Integrated pest management Data-driven irrigation systems |

| 7—Equipment and internal environment | The design, maintenance, and condition of the physical equipment and local operational environments. | Equipment availability Technological innovation Maintenance capacity | Equipment performance Workplace safety Production efficiency | Availability of automated machinery Use of renewable energy sources on farms Implementation of robotics in food processing |

| 8—People | The values, skills, attitudes, and wellbeing of individuals involved in the system—farm owners/managers, farm workers, consumers, policy makers | Education Training Social norms Health and wellbeing | Behavioral changes Workforce capability Community resilience | Farmer training in digital tools Stakeholder engagement in policy design Public trust in agri-technology |

| Inclusion Level | Inclusion Activity | Government (Policy and Budgeting) | Regulatory Bodies and Associations | Local Government (Policy and Budgeting) | Organizations, Management, Environment | People |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level 1: Inclusion of Intention | Explicit commitments or stated goals to ensure relevant stakeholders are embedded in project planning documents and policy frameworks from the outset. These stakeholders will be from both national and regional settings. | Develop national strategies that require inclusive planning and stakeholder input. | Set expectations for stakeholder representation in funding frameworks and standards. | Embed stakeholder representation in local development and technology strategies, e.g., in Lincolnshire the Lincolnshire Food Valley initiative. | Consult with producer groups, environmental NGOs, and agri-technology networks. | Express interests, concerns, and priorities at the earliest stages. |

| Level 2: Inclusion of Consumption | End-users (e.g., farmers, cooperatives) are actively engaged in pilot projects or trials, providing real-time feedback on the usability and effectiveness of agri-technologies. This stage of engagement ensures place-based impact. | Fund real-life demonstration programs that promote stakeholder participation. | Support collaborative, multi-stakeholder workgroups Monitor performance and user inclusion in pilot initiatives and regulatory sandboxes. | Identify suitable pilot adoption sites and lead local engagement with farmer innovation networks. | Implement governance infrastructures, place-based impact accelerators such as LINCAM Ceres [86] and coordinate feedback mechanisms to deliver place-based impact. | Develop farmer and community networks to support participation in trials and testing and provide experiential feedback. |

| Level 3: Inclusion of Impact | Regular impact assessments are conducted, surveying both direct participants (e.g., technology adopters) and affected non-participating stakeholders to gauge broader socio-economic effects. This stage will consider socio-economic and environmental factors such as displacement of labor, impact on diffuse pollution from agricultural land, improvements in animal welfare etc. | Support regional impact evaluations and incorporate findings into policy. | Use impact data to inform regulatory review processes, e.g., the UK Industrial Strategy. Inform strategic funding of research and development in core impactful industrial sectors including agri-tech. | Facilitate local feedback collection and knowledge exchange forums. Provide opportunities for knowledge exchange which can feed into local policy innovation and through to national policy. | Conduct assessments and collect operational data. Provide opportunities for knowledge exchange which can feed into local policy innovation and through to national policy. | Contribute lived experience and reflections on the impact of technology. Provide opportunities for knowledge exchange which can feed into local policy innovation and through to national policy. Consider the impact on migrant harvest workers specifically who are engaging with place to ensure inclusion and appropriate impact assessment. |

| Level 4: Inclusion of Process | Participatory workshops or collaborative design sessions actively integrate stakeholder perspectives into technology design, adaptation, and implementation strategies. The development of inclusive processes of innovation will ensure both responsible research and innovation and inclusive innovation and that the processes themselves are fair, just and non-exclusionary. | Promote participatory approaches in innovation funding schemes. | Encourage inclusive design in technical and advisory guidance. | Co-lead collaborative design sessions with stakeholders. | Facilitate multi-actor workshops and inclusive design processes. Consider how participation can be encouraged from silent sectors of communities who have preciously not engaged in micro- and small business advocacy activities to promote inclusive and just transition. | Co-design solutions and influence implementation approaches. Consider how participation can be encouraged from silent communities who have preciously not engaged in community advocacy to promote inclusive and just transition. |

| Level 5: Inclusion of Structure | Stakeholder feedback is formalized within institutional processes and consistently informs strategic decisions and policies regarding agri-technology development and use. This stage will ensure that there is a focus not only on spatial consciousness but also the spatial connectedness and an integration of economic growth interventions and aspects of place-making. | Require multi-stakeholder governance structures in funded projects. | Include community representation in formal advisory groups. | Create permanent local governance mechanisms for oversight. Develop adaption and mitigation strategies for communities that are affected by spatial development, e.g., addressing loss of services and community spaces. | Integrate feedback processes into operational structures and develop adaption and mitigation strategies at the organizational level, e.g., retraining programs, redeployment programs for staff that are affected. | Contribute structured input through formal consultation processes; participate in scheduled reviews or standing committees. |

| Level 6: Post-structural inclusion | Stakeholders (e.g., farmers, local communities) have ongoing roles in governance, decision-making boards, or advisory committees shaping technology deployment and land use planning. This stage ensures that aspects of spatial connectedness continue to be central to spatial development strategies. | Enable legal or institutional pathways for community co-governance. | Adapt policy mechanisms to reflect shared governance and oversight. | Support and fund local advisory boards with long-term responsibilities. | Institutionalize bottom–up accountability and review structures. | Develop skills and capacity so individuals have confidence to participate in governance structures (e.g., community boards, land-use planning panels), with co-decision-making responsibilities. Consider the involvement of all place-based communities including migrant workers. |

5. Concluding Thoughts

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Defra | Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs |

| EDP | Environmental Delivery Plan |

| NGO | Non Governmental Organisation |

| NRF | Nature Recovery Fund |

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

| UK | United Kingdom |

References

- Sonnino, R.; Marsden, T.; Moragues-Faus, A. Relationalities and convergences in food security narratives: Towards a place-based approach. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 2016, 41, 477–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, L. Innovating in an Uncertain World: Understanding the Social, Technical and Systemic Barriers to Farmers Adopting New Technologies. Challenges 2024, 15, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krauss, W.; Bremer, S. The role of place-based narratives of change in climate risk governance. Clim. Risk Manag. 2020, 28, 100221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wester-Herber, M. Underlying concerns in land-use conflicts—The role of place-identity in risk perception. Environ. Sci. Policy 2004, 7, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, C.S.; Fynbo, L. Social Stigmatization of Pig Farmers: Medical Perspectives on Modern Pig Farming. In Risking Antimicrobial Resistance: A Collection of One-Health Studies of Antibiotics and Its Social and Health Consequences; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lähdesmäki, M.; Siltaoja, M.; Luomala, H.; Puska, P.; Kurki, S. Empowered by stigma? Pioneer organic farmers’ stigma management strategies. J. Rural. Stud. 2019, 65, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naylor, R.; Hamilton-Webb, A.; Little, R.; Maye, D. The ‘good farmer’: Farmer identities and the control of exotic livestock disease in England. Sociol. Rural. 2018, 58, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerink, J.; Pleijte, M.; Schrijver, R.; van Dam, R.; de Krom, M.; de Boer, T. Can a ‘good farmer’ be nature-inclusive? Shifting cultural norms in farming in The Netherlands. J. Rural. Stud. 2021, 88, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigors, B.; Wemelsfelder, F.; Lawrence, A.B. What symbolises a “good farmer” when it comes to farm animal welfare? J. Rural. Stud. 2023, 98, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, L.; Dooley, J.J.; Dunsford, I.; Goodman, M.K.; MacMillan, T.C.; Morgans, L.C.; Rose, D.C.; Sexton, A.E. Threat or opportunity? An analysis of perceptions of cultured meat in the UK farming sector. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7, 1277511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schillo, R.S.; Robinson, R.M. Inclusive innovation in developed countries: The who, what, why, and how. Technol. Innov. Manag. Rev. 2017, 7, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meij, E.; Haartsen, T.; Meijering, L. Enduring rural poverty: Stigma, class practices and social networks in a town in the Groninger Veenkoloniën. J. Rural. Stud. 2020, 79, 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biddau, F.; D’Oria, E.; Brondi, S. Coping with territorial stigma and devalued identities: How do social representations of an environmentally degraded place affect identity and agency? Sustainability 2023, 15, 2686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selfa, T.; Marini, V.; Abrams, J. Place attachment and perceptions of land-use change: Cultural ecosystem services impacts of eucalyptus plantation expansion in Ubajay, Entre Ríos, Argentina. Ecol. Soc. 2021, 26, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Strijker, D.; Wu, Q. Place identity: How far have we come in exploring its meanings? Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Yan, S.; Strijker, D.; Wu, Q.; Chen, W.; Ma, Z. The influence of place identity on perceptions of landscape change: Exploring evidence from rural land consolidation projects in Eastern China. Land Use Policy 2020, 99, 104891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proshansky, H.M. The city and self-identity. Environ. Behav. 1978, 10, 147–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davoudi, S.; Strange, I. (Eds.) Conceptions of Space and Place in Strategic Spatial Planning; Routledge: London, UK, 2009; pp. 7–42. [Google Scholar]

- Davoudi, S. The legacy of positivism and the emergence of interpretive tradition in spatial planning. Region. Stud. 2012, 46, 429–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galland, D.; Grønning, M. Spatial consciousness. In The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopaedia of Urban and Regional Studies; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defra. (Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs) Land Use Framework for England. 2025. Available online: https://consult.defra.gov.uk/land-use-framework/land-use-consultation/supporting_documents/Land%20Use%20Consultation.pdf (accessed on 2 March 2025).

- Lingham, S.; Kowalska, A.; Kowalski, J.; Maye, D.; Manning, L. The potential impact of Brexit on UK food standards and food security: Perspectives of repositioning neoliberalist policy. Foods 2025, 14, 1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BBC (British Broadcasting Company). What on Earth Is a Yellowbelly? 2014. Available online: https://www.bbc.co.uk/lincolnshire/asop/people/what_is_a_yellowbelly.shtml (accessed on 13 March 2025).

- Anton, C.E.; Lawrence, C. The relationship between place attachment, the theory of planned behaviour and residents’ response to place change. J. Environ. Psychol. 2016, 47, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayitno, G.; Rukmi, W.I.; Ashari, M.I. Assessing the social factors of place dependence and changes in land use in sustainable agriculture: Case of Pandaan District, Pasuruan Regency, Indonesia. J. Socioecon. Dev. 2021, 4, 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trąbka, A. From functional bonds to place identity: Place attachment of Polish migrants living in London and Oslo. J. Environ. Psychol. 2019, 62, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R. The inherited city as a resource. In The Built Environment: Creative Enquiry into Design and Planning; Crisp: Menlo Park, CA, USA, 1994; pp. 253–263. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/37051017/The_Built_Environment_A_Collaborative_Inquiry_Into_Design_and_Planning_2nd_Edi_3 (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- Williams, D.R.; Vaske, J.J. The measurement of place attachment: Validity and generalizability of a psychometric approach. For. Sci. 2003, 49, 830–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greider, T.; Garkovich, L. Landscapes: The social construction of nature and the environment. Rural. Sociol. 1994, 59, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, A. “My father wasn’t really interested in machinery”: New perspectives on the modernisation of agriculture in 20th century Lincolnshire. Int. J. Reg. Local Hist. 2016, 11, 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sousa Jabbour, A.B.L.; Jabbour, C.J.C.; Foropon, C.; Godinho Filho, M. When titans meet–Can industry 4.0 revolutionise the environmentally-sustainable manufacturing wave? The role of critical success factors. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2018, 132, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morella, P.; Lambán, M.P.; Royo, J.; Sánchez, J.C. Study and analysis of the implementation of 4.0 technologies in the agri-food supply chain: A state of the art. Agronomy 2021, 11, 2526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coronado, E.; Kiyokawa, T.; Ricardez, G.A.G.; Ramirez-Alpizar, I.G.; Venture, G.; Yamanobe, N. Evaluating quality in human-robot interaction: A systematic search and classification of performance and human-centered factors, measures and metrics towards an industry 5.0. J. Manuf. Syst. 2022, 63, 392–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hervas-Oliver, J.L.; Estelles-Miguel, S.; Mallol-Gasch, G.; Boix-Palomero, J. A place-based policy for promoting Industry 4.0: The case of the Castellon ceramic tile district. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2019, 27, 1838–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panori, A.; Kakderi, C.; Komninos, N.; Fellnhofer, K.; Reid, A.; Mora, L. Smart systems of innovation for smart places: Challenges in deploying digital platforms for co-creation and data-intelligence. Land Use Policy 2021, 111, 104631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RPG (Rural Policy Group). The Sustainable Food Report 2022. Available online: https://ruralpolicygroup.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/RPG-Sustainable-Food-Report-2023.pdf (accessed on 18 March 2025).

- Kowalska, A.; Manning, L. Using the rapid alert system for food and feed: Potential benefits and problems on data interpretation. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 61, 906–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, S.; Khatooni, M. Saturation in qualitative research: An evolutionary concept analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. Adv. 2024, 6, 100174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fusar Poli, E.; Fontefrancesco, M.F. Trends in the implementation of biopesticides in the Euro-Mediterranean region: A narrative literary review. Sustain. Earth Rev. 2024, 7, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Applications of Case Study Research; SAGE Publications: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Cash-Gibson, L.; Martinez-Herrera, E.; Escrig-Pinol, A.; Benach, J. Why and how Barcelona has become a health inequalities research hub? A realist explanatory case study. J. Crit. Realism 2023, 22, 49–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fincher, R.; Pardy, M.; Shaw, K. Place-making or place-masking? The everyday political economy of “making place”. Plan. Theory Pract. 2016, 17, 516–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimer, B.; Markey, S. Place-Based Policy: A Rural Perspective. Community Research Connexions. Funded by Human Resources and Social Development Canada. 2008. Available online: https://billreimer.net/research/files/ReimerMarkeyRuralPlaceBasedPolicySummaryPaper20081107.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Barca, F.; McCann, P.; Rodríguez-Pose, A. The case for regional development intervention: Place-based versus place-neutral approaches. J. Reg. Sci. 2012, 52, 134–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busso, M.; Gregory, J.; Kline, P. Assessing the incidence and efficiency of a prominent place based policy. Am. Econ. Rev. 2013, 103, 897–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumark, D.; Simpson, H. Place-based policies. In Handbook of Regional and Urban Economics; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; Volume 5, pp. 1197–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klepac, B.; Mowle, A.; Riley, T.; Craike, M. Government, governance, and place-based approaches: Lessons from and for public policy. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2023, 21, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, P.B.; Oberg, A.; Nelson, L. Rural gentrification and linked migration in the United States. J. Rural. Stud. 2010, 26, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, M. Rural gentrification and the processes of class colonization. J. Rural. Stud. 1993, 9, 123–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, M.; Smith, D.; Brooking, H.; Duer, M. Re-placing displacement in gentrification studies: Temporality and multidimensionality in rural gentrification displacement. Geoforum 2021, 118, 66–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korir, L.; Drake, A.; Collison, M.; Camacho Villa, C.; Sklar, E.; Pearson, S.; Manning, L. Investing in technology to address labour shortages in UK fresh produce and horticulture: How does this redefine standards of good agricultural practice? Local Econ. 2024, 29, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, D.C.; Wheeler, R.; Winter, M.; Lobley, M.; Chivers, C.A. Agriculture 4.0: Making it work for people, production, and the planet. Land Use Policy 2021, 100, 104933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dono, G.; Cortignani, R.; Dell’Unto, D.; Deligios, P.; Doro, L.; Lacetera, N.; Mula, L.; Pasqui, M.; Quaresima, S.; Vitali, A.; et al. Winners and losers from climate change in agriculture: Insights from a case study in the Mediterranean basin. Agric. Syst. 2016, 147, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, L.; Brewer, S.; Craigon, P.J.; Frey, J.; Gutierrez, A.; Jacobs, N.; Kanza, S.; Munday, S.; Sacks, J.; Pearson, S. Reflexive governance architectures: Considering the ethical implications of autonomous technology adoption in food supply chains. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 133, 114–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Guardian. Campaigners Get Go-Ahead to Challenge Plans for Oilfield in Lincolnshire Wolds. 4 March 2024. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2024/mar/04/campaigners-get-go-ahead-to-challenge-plans-for-oilfiield-in-lincolnshire-wolds (accessed on 28 May 2025).

- The Times. Solar Power Developers Held Up by Search for Buried Relics. 12 February 2025. Available online: https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/solar-power-developers-held-up-by-search-for-buried-relics-sxzfnt9lj (accessed on 28 May 2025).

- Smithers, R. Lincolnshire’s US-Style ‘Mega’ Dairy Farm on Hold as Plans Are Withdrawn. The Guardian, 16 February 2011. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2011/feb/16/lincolnshire-mega-dairy-farm-plans-withdrawn (accessed on 28 May 2025).

- Planning Inspectorate. Appeal Decision: Winterton Solar Farm. January 2023. Available online: https://www.shropshire.gov.uk/media/27497/cd-722-winterton-solar-decision.pdf (accessed on 28 May 2025).

- Klerkx, L.; Jakku, E.; Labarthe, P. A review of social science on digital agriculture, smart farming and agriculture 4.0: New contributions and a future research agenda. NJAS-Wagening. J. Life Sci. 2019, 90, 100315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newell, P.; Mulvaney, D. The political economy of the ‘just transition’. Geogr. J. 2013, 179, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Chen, Y.; Chang, W.Y. Place Attachment, Self-Efficacy, and Farmers’ Farmland Quality Protection Behavior: Evidence from China. Land 2023, 12, 1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roddis, P.; Roelich, K.; Tran, K.; Carver, S.; Dallimer, M.; Ziv, G. What shapes community acceptance of large-scale solar farms? A case study of the UK’s first ‘nationally significant’ solar farm. Sol. Energy 2020, 209, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greater Lincolnshire Local Enterprise. Agri-Food Sector. 2025. Available online: https://www.greaterlincolnshirelep.co.uk/priorities-and-plans/sectors/agri-food-sector/ (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- Greater Lincolnshire Local Enterprise Partnership. Agri-Food Sector Plan. 2017. Available online: https://www.greaterlincolnshirelep.co.uk/assets/documents/8012_GL_LEP_2017_Agri_Food_Plan_2017_WEB.pdf (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- UK Food Valley. 2025. Available online: https://www.greaterlincolnshirelep.co.uk/funding-and-projects/uk-food-valley/ (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- Official Statistics—Total Income from Farming in the East Midlands. Updated 30 October 2024. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/total-income-from-farming-for-the-regions-of-england/total-income-from-farming-in-the-east-midlands (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- Agriculture Across Lincolnshire. 2022. Available online: https://lincolnshire.moderngov.co.uk/documents/s57979/Appendix%20B%20-%20Agriculture%20Across%20Lincolnshire-%20Evidence%20Considered.pdf (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- De Roest, K.; Ferrari, P.; Knickel, K. Specialisation and economies of scale or diversification and economies of scope? Assessing different agricultural development pathways. J. Rural. Stud. 2018, 59, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- His Majesty’s Government. Guide to the Planning and Infrastructure Bill. 2025. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-planning-and-infrastructure-bill/guide-to-the-planning-and-infrastructure-bill (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- His Majesty’s Government. Factsheet: Strategic Planning. 2025. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-planning-and-infrastructure-bill/factsheet-strategic-planning (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- Planning and Infrastructure Bill. Available online: https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/bills/cbill/59-01/0250/240250.pdf (accessed on 28 May 2025).

- His Majesty’s Government. Factsheet: Nature Restoration Fund. 2025. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-planning-and-infrastructure-bill/factsheet-nature-restoration-fund (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- OECD. Policy Guidance: Enabling Inclusive Governance; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Partnership for Education. Paving Pathways for Inclusion: 3 Levers Countries Can Use to Include Refugees in Education Systems. 2024. Available online: https://www.globalpartnership.org/blog/paving-pathways-inclusion-3-levers-countries-can-use-include-refugees-education-systems (accessed on 22 January 2025).

- Schot, J.; Steinmueller, W.E. Three frames for innovation policy: R&D, systems of innovation and transformative change. Res. Policy 2018, 47, 1554–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geels, F.W. The multi-level perspective on sustainability transitions: Responses to seven criticisms. Environ. Innov. Soc. Trans. 2011, 1, 24–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geels, F.W. From sectoral systems of innovation to socio-technical systems: Insights about dynamics and change from sociology and institutional theory. Res. Policy 2004, 33, 897–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, R.; Waterson, P. ‘When Food Kills’: A socio-technical systems analysis of the UK Pennington 1996 and 2005 E. coli O157 Outbreak reports. Saf. Sci. 2016, 86, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svedung, I.; Rasmussen, J. Graphic representation of accident scenarios: Mapping system structure and the causation of accidents. Saf. Sci. 2002, 40, 397–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mungai, P.; Jimenez, A.; Kleine, D.; Van Belle, J.P. The role of the marginalized and unusual suspects in the production of digital innovations: Models of innovation in an African context. In International Development Informatics Association Conference; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 261–278. [Google Scholar]

- Chataway, J.; Hanlin, R.; Kaplinsky, R. Inclusive innovation: An architecture for policy development. Innov. Dev. 2014, 4, 33–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geels, F.W.; Sovacool, B.K.; Schwanen, T.; Sorrell, S. Sociotechnical transitions for deep decarbonization. Science 2017, 357, 1242–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henfridsson, O.; Nandhakumar, J.; Scarbrough, H.; Panourgias, N. Recombination in the open-ended value landscape of digital innovation. Inf. Organ. 2018, 28, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buck, C.; Krombacher, A.; Röglinger, M.; Körner-Wyrtki, K. Doing good by going digital: A taxonomy of digital social innovation in the context of incumbents. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2023, 32, 101806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exciting New Phase for Ceres Agri-Tech. Available online: https://www.ceresagritech.org/about/ (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Powell, J.M.; Shibeika, A. Brexit and beyond: Addressing skills shortage in the UK construction industry. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. Manag. Procure. Law 2025, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLeod, G.; Jones, M. Renewing the Geography of Regions. Environ. Plan. D Soc. Space 2001, 9, 669–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macleod, G.; Jones, M. Territorial, scalar, networked, connected: In what sense a ‘regional world’? Reg. Stud. 2007, 41, 1177–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| External Appearance | Internal Thoughts | |

|---|---|---|

| People | Physical appearance (physical traits, dress, physical aptitude). Behavior (diet, dialect, practices). | Attitude (goals, aspirations, preferences) Feelings (sense of belonging, self-identification with place(s), e.g., place where born, place where farming, feelings towards traditional breeds of farm animals or crops associated with place). Memory and nostalgia: personal or familial histories tied to the land. Values and ethics: stewardship, sustainability, custodianship of the land. Perceptions of change: attitudes toward land use change (e.g., resistance to urbanization). |

| Place | Physical shape (landscape, infrastructure, terroir aspects (water, temperature, sunshine hours), soil classification, land use). Symbolic shape (boundary on the map, place names, historical landmarks, e.g., cathedrals, castles, natural places of significance—sites of special scientific interest). Institutional shape (governance, services, provisions for education, health, business development support). | Collective perception (discourse about the place, marketing of the place) Individual perception (boundaries of place, representative elements of place) Sense of continuity: perceptions of place over time. Cultural meanings: stories, myths, or folklore attached to a place. Place-based identity politics: inclusion/exclusion (e.g., who belongs, who is considered ‘local’). Perceived agency: belief in ability to influence land use decisions or governance. |

| Area of Work | Industry 4.0 Characteristics | Industry 5.0 Characteristics | Example KPI (4.0) | Example KPI (5.0) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AREA framework implementation for responsible innovation by designers | Process standardization | Ethical innovation, responsible technology adoption | Adoption rate of AREA framework by designers (%) to ensure safe adoption of technology | Number of stakeholder consultations per design cycle; reduction in people days lost due to workplace injury (as a % of work year) |

| Development of autonomous machinery | Automation to address labor shortages, data-driven decision making | Human–robot collaboration, adapting farming system to societal needs to promote sustainability | Performance speed (e.g., picks per minute) | Reduction in food waste (%) through automation |

| Food safety and quality mapping to inform effective management | Optimizing for compliance and reduction in food safety incidents | Human–tech collaboration adapting food safety and quality management systems to ensure reasonable precautions and due diligence | Number of food safety and quality incidents per operational hour | Reduction in incidents of foodborne disease, deaths, hospitalizations and illness |

| Hygienic design of machine hardware | Optimized for compliance and reduction in food safety incidents | Sustainability-focused materials, human health consideration | Number of food safety incidents per operational hour | Use of sustainable, food-safe materials (%) |

| KPI development | Performance metrics (speed, accuracy, efficiency) | Broader impact (worker well-being, environmental impact) | Pick accuracy (%), ROI | Reduction in workplace injuries through automation of tasks (i.e., interacting with ergonomically designed robots may cause fewer repetitive strain injuries than manual harvesting as a % of work year) |

| Spatial Development (Space-Making) | Place-Making | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Economic | Agriculture Jobs Property values Tourism | Aesthetic | Glint and glare (from technology adoption, e.g., solar panels) Landscape Vista |

| Environmental | Carbon (greenhouse gas emissions) Flooding Wildlife and habitats (biodiversity) | Impact | Air pollution Cumulative impacts Light pollution Noise pollution Traffic |

| Process | Alternative options Mitigation measures Trust and transparency | Social | Health and wellbeing Place attachment Recreation |

| Life-cycle | Business model Design End-of-life/site remediation Project scale Technology | Temporal | Heritage Legacy |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Manning, L.; Grant, J.H. Place-Based Impact: Accelerating Agri-Technology Adoption in an Evolving ‘Place’. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5292. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125292

Manning L, Grant JH. Place-Based Impact: Accelerating Agri-Technology Adoption in an Evolving ‘Place’. Sustainability. 2025; 17(12):5292. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125292

Chicago/Turabian StyleManning, Louise, and Jack H. Grant. 2025. "Place-Based Impact: Accelerating Agri-Technology Adoption in an Evolving ‘Place’" Sustainability 17, no. 12: 5292. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125292

APA StyleManning, L., & Grant, J. H. (2025). Place-Based Impact: Accelerating Agri-Technology Adoption in an Evolving ‘Place’. Sustainability, 17(12), 5292. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125292