Reframing Sustainability in Post-Mining Landscapes: A Foundational Framework for Institutional and Behavioral Integration in Indonesia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design and Theoretical Foundation

2.2. Data Collection and Analytical Strategy

2.3. Coding Framework Development and NVivo Analysis

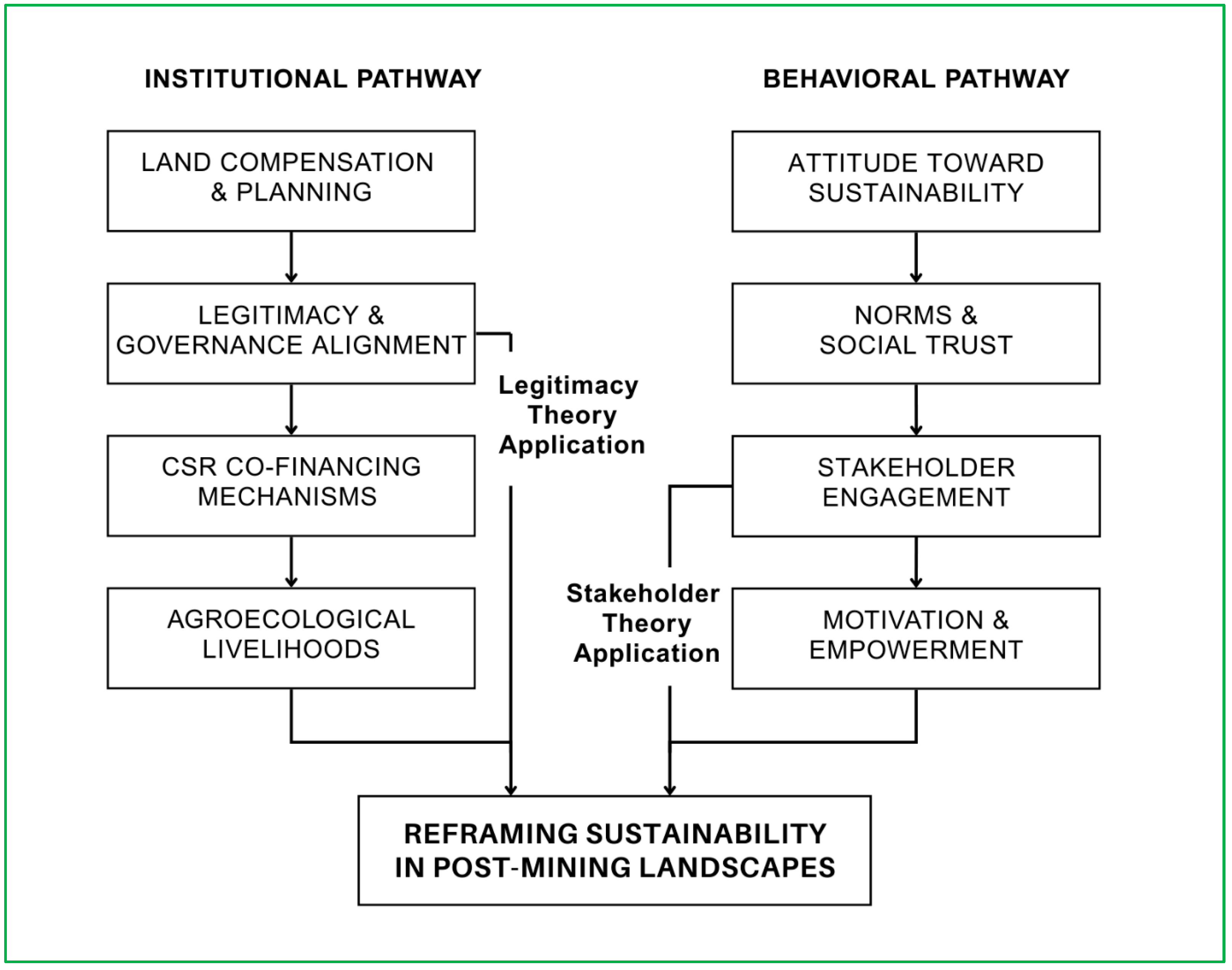

2.4. Operationalizing the Dual-Pathway Framework

2.5. Contextual Framing: The Post-Mining Problem in Indonesia

2.6. Research Validity and Analytical Rigor

2.7. Research Limitations and Methodological Reflection

3. Results

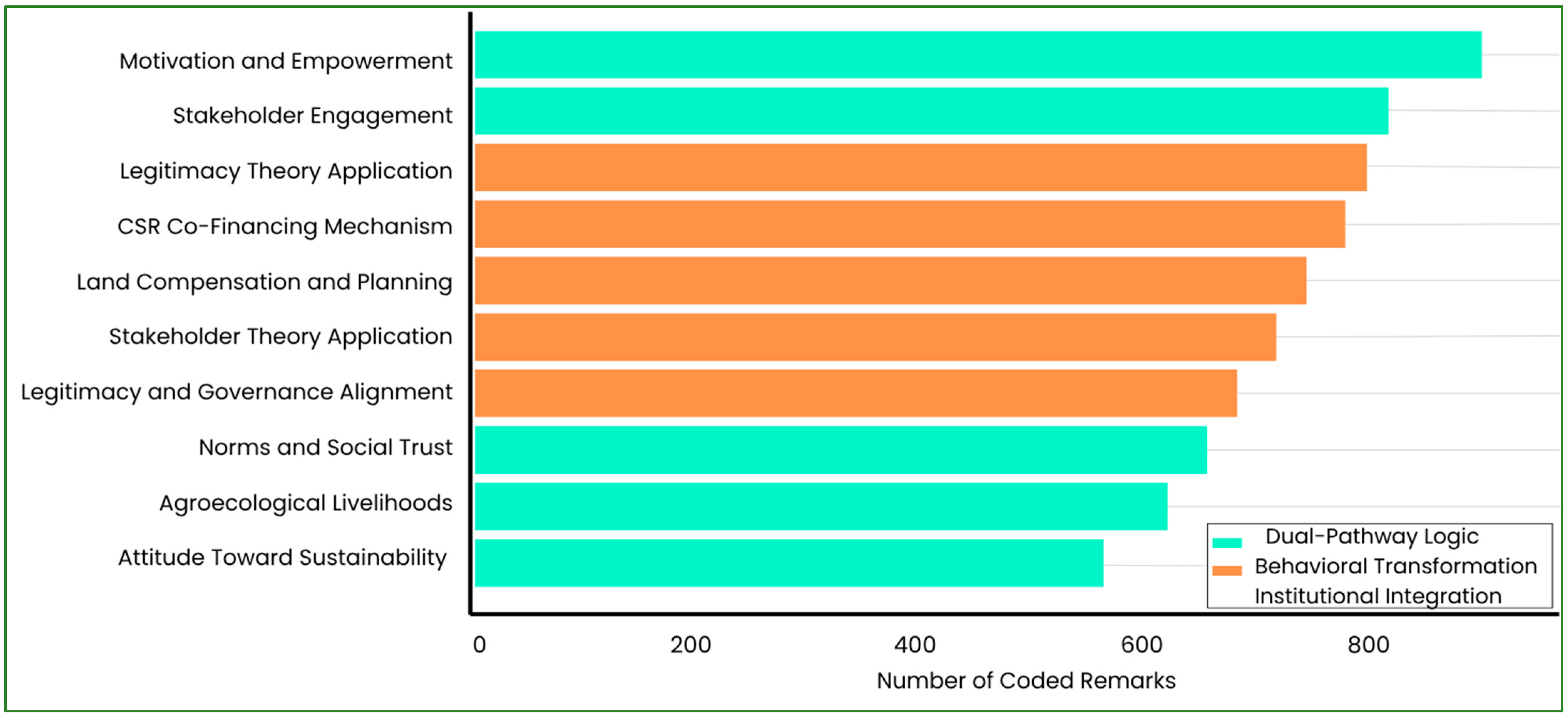

3.1. Empirical Overview of Thematic Patterns

3.2. Institutional Integration Themes

3.2.1. Land Compensation and Planning

3.2.2. Legitimacy and Governance Alignment

3.2.3. CSR Co-Financing Mechanisms

3.2.4. Agroecological Livelihoods

3.3. Behavioral Integration Themes

3.3.1. Attitude Toward Sustainability

3.3.2. Norms and Social Trust

3.3.3. Stakeholder Engagement

3.3.4. Motivation and Empowerment

3.4. Cross-Cutting Tensions and Stakeholder Contradictions

3.4.1. Fragmented Institutional Intent vs. Behavioral Reality

3.4.2. Top–Down Policies Undermining Local Agency

3.4.3. Symbolic Participation and Distrust

3.4.4. Institutional Rigidity vs. Behavioral Adaptation

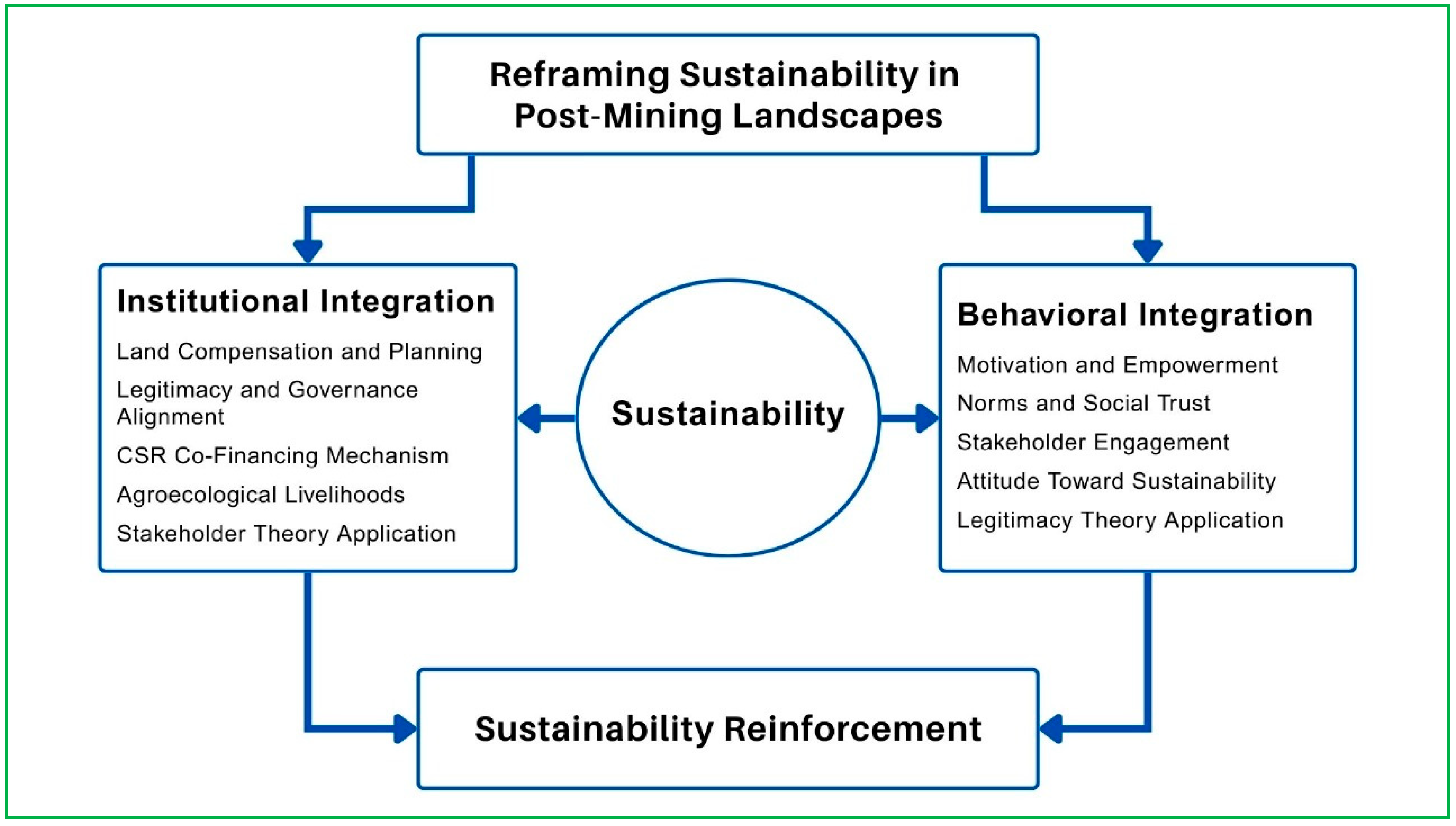

3.4.5. Toward a Reinforcing Model of Sustainability Integration

3.5. Strategic Insights, Limitations, and Future Pathways

3.6. Policy and Governance Implications

3.7. Practical Implications for Community Empowerment

4. Conclusions and Policy Recommendation

- Anchor post-mining recovery in agroecological and community-driven livelihood systems, such as cacao-based cooperatives, to generate economic and environmental resilience.

- Align land compensation mechanisms with legitimacy frameworks, ensuring transparency, consent, and spatial justice in post-mining land redistribution.

- Co-design CSR initiatives through inclusive, multi-stakeholder processes, minimizing elite capture and enhancing community ownership.

- Establish local empowerment institutions (e.g., cooperatives, training centers, or participatory councils) as long-term platforms for behavioral transformation and livelihood restoration.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Parent Nodes and Conceptual Definition

| # | Parent Nodes | Conceptual Definition |

| 1 | Land Compensation and Planning | Refers to inclusive and participatory mechanisms to ensure fair and transparent land redistribution, compensation, and use planning in post-mining contexts. This includes recognizing customary rights, participatory mapping, and integrating community livelihoods into spatial strategies. |

| 2 | Legitimacy and Governance Alignment | Focuses on aligning institutional structures and governance procedures with community expectations, regulatory transparency, and policy legitimacy. It emphasizes trust-building, transparency in licensing, and participatory regulatory reform. |

| 3 | CSR Co-Financing Mechanism | Denotes the strategic use of CSR resources as co-financing instruments for sustainable recovery in post-mining regions, ensuring alignment between company initiatives and community needs through accountable, inclusive, and long-term funding models. |

| 4 | Agroecological Livelihoods | Refers to ecological and culturally grounded farming practices such as cacao-based systems, agroforestry, and intercropping that provide sustainable income, restore ecosystems, and empower communities in post-mining areas. |

| 5 | Attitude toward Sustainability | Captures community perceptions, beliefs, and behavioral intentions toward sustainable land use, emphasizing willingness to adopt restoration practices, long-term stewardship, and environmental identity transformation. |

| 6 | Norms and Social Trust | Highlights the cultural, ethical, and social norms that guide behavior in land reclamation, including adherence to communal rules, trust in institutions, and the role of adat (customary) systems in shaping sustainable transitions. |

| 7 | Stakeholder Engagement | Encompasses mechanisms for meaningful and continuous interaction among diverse stakeholders—government, private sector, communities, and Indigenous groups—through dialogue, partnership, and collaborative planning in post-mining development. |

| 8 | Motivation and Empowerment | Refers to the internal and external drivers of change that enhance individuals’ and communities’ capabilities to act, including access to training, resources, recognition, and support systems that foster transformation agency. |

| 9 | Legitimacy Theory Application | Explores how various forms of legitimacy—pragmatic, moral, and cognitive—are constructed and perceived in post-mining governance, affecting institutional trust, policy acceptance, and social license to operate. |

| 10 | Stakeholder Theory Application | Applies stakeholder theory to understand how diverse interests are identified, prioritized, and integrated into decision-making, highlighting power dynamics, engagement strategies, and the distribution of benefits and responsibilities. |

Appendix B. Parent Nodes and Child Nodes

| # | Child Node | Child Node Definition | Frequencies |

| 1.1 | Access to microfinance | Access to small loans and financial services | 151 |

| 1.2 | Community-led initiatives | Initiatives led by local actors without external mandates | 90 |

| 1.3 | Decision-making autonomy | Freedom and capacity to make decisions about land use | 83 |

| 1.4 | Local entrepreneurship incentives | Support for creating small local businesses post-mining | 195 |

| 1.5 | Psychological resilience | Psychological strength to cope with transition and risks | 95 |

| 1.6 | Recognition and reward mechanisms | Acknowledgement of community achievements and contributions | 121 |

| 1.7 | Training and skills development | Skill-building initiatives supporting post-mining livelihoods | 84 |

| 1.8 | Visioning and goal setting | Envisioning a desirable future and setting goals for it | 94 |

| 2.1 | Dialogues with Indigenous communities | Consultation and negotiations with Indigenous communities | 87 |

| 2.2 | Engagement mapping | Mapping and understanding stakeholders’ interests and influence | 93 |

| 2.3 | Farmer cooperatives role | Role of farmer groups in mobilizing and implementing programs | 92 |

| 2.4 | Gender-inclusive representation | Ensuring gender balance in participation and benefits | 186 |

| 2.5 | Grievance redressal systems | Systems for addressing grievances and resolving complaints | 93 |

| 2.6 | Multi-stakeholder forums | Structured forums involving multiple stakeholder groups | 90 |

| 2.7 | NGO involvement | NGO participation in planning, advocacy, and oversight | 89 |

| 2.8 | Participation in planning | Inclusive decision-making in local development planning | 88 |

| 3.1 | Cognitive legitimacy patterns | Public comprehension of organizational roles and actions | 91 |

| 3.2 | Institutional credibility | Belief in the reliability and performance of institutions | 98 |

| 3.3 | Legitimacy crises | Breakdowns in legitimacy due to failures or crises | 93 |

| 3.4 | Moral legitimacy indicators | Moral judgment of the rightness of institutional behavior | 92 |

| 3.5 | Perception of fairness | Perceived fairness in decisions and treatment by institutions | 152 |

| 3.6 | Pragmatic legitimacy cues | Tangible signs of usefulness in institutional performance | 95 |

| 3.7 | Reputation management | Management of public image and institutional reputation | 92 |

| 3.8 | Role of transparency | Use of transparency as a legitimacy-enhancing practice | 95 |

| 4.1 | Allocation of CSR funds | Budget allocation strategies for CSR to support reclamation and livelihoods | 93 |

| 4.2 | Cross-sector CSR alignment | Coordination between different sectors to enhance CSR effectiveness | 87 |

| 4.3 | CSR for livelihood transition | Use of CSR funds to support vocational training and farming transitions | 95 |

| 4.4 | CSR reporting standards | Standards used to evaluate CSR practices and sustainability impact | 147 |

| 4.5 | Linking CSR to SDGs | Aligning CSR activities with Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) | 92 |

| 4.6 | Monitoring CSR outcomes | Tracking the results and impacts of CSR-funded projects | 86 |

| 4.7 | Multi-year budgeting schemes | Planning CSR funds across multiple years to support continuity | 93 |

| 4.8 | Public-private partnerships | Collaborative funding models between corporations and public bodies | 93 |

| 5.1 | Conflict resolution over land | Processes to resolve disputes over overlapping or contested land claims | 85 |

| 5.2 | Customary land rights recognition | Recognition of traditional land rights based on local customs (adat) and Indigenous claims | 83 |

| 5.3 | Land asset valuation | Assessment of land value for fair compensation and reclamation planning | 89 |

| 5.4 | Legal harmonization for land status | Legal synchronization between customary and formal land regulations | 90 |

| 5.5 | Long-term land use strategy | Strategic planning for sustainable and long-term use of reclaimed land | 63 |

| 5.6 | Participatory land mapping | Mapping land use collaboratively with communities to define post-mining allocations | 89 |

| 5.7 | Resettlement planning | Planning and implementation of equitable resettlement programs | 181 |

| 5.8 | Spatial zoning for post-mining use | Designating zones for agriculture, housing, conservation in reclaimed mining areas | 86 |

| 6.1 | Balancing stakeholder claims | Strategies for equitably addressing conflicting stakeholder needs | 93 |

| 6.2 | Conflict mediation strategies | Techniques for resolving stakeholder-related disputes | 92 |

| 6.3 | Institutional responsiveness | Institutional ability to respond to stakeholder input | 96 |

| 6.4 | Managing stakeholder expectations | Efforts to manage and align stakeholder expectations | 89 |

| 6.5 | Power–legitimacy–urgency typology | Framework assessing power, legitimacy, and urgency of actors | 97 |

| 6.6 | Salience-based prioritization | Prioritization of stakeholders based on legitimacy and urgency | 94 |

| 6.7 | Stakeholder dialogue frameworks | Protocols for inclusive dialogue and consensus-building | 89 |

| 6.8 | Stakeholder mapping tools | Tools for mapping influence and role of stakeholders | 97 |

| 7.1 | Anti-corruption safeguards | Measures to prevent corruption in mining and reclamation programs | 133 |

| 7.2 | Community consultation mechanisms | Mechanisms for engaging local communities in project planning stages | 92 |

| 7.3 | Compliance with EIA or AMDAL | Ensuring compliance with EIA (AMDAL) and environmental safeguards | 30 |

| 7.4 | Institutional trust building | Efforts to rebuild institutional credibility and public trust | 90 |

| 7.5 | Policy coherence across agencies | Harmonization of regulations and planning across multiple government agencies | 94 |

| 7.6 | Regulatory enforcement capacity | Capacity of institutions to enforce environmental and land-use policies | 91 |

| 7.7 | Role of local government | Local government roles in monitoring, planning, and enforcing land rehabilitation | 89 |

| 7.8 | Transparent permitting process | Openness and accountability in the process of issuing mining permits | 92 |

| 8.1 | Community rule adherence | Respecting traditional norms and social rules in land matters | 87 |

| 8.2 | Intergenerational knowledge | Transferring knowledge across generations about land and nature | 95 |

| 8.3 | Local leadership influence | Influence of local leaders on land and governance decisions | 92 |

| 8.4 | Norms of environmental care | Social expectations regarding care for the environment | 91 |

| 8.5 | Reciprocity in group behavior | Mutual aid and social reciprocity in sustainability practices | 72 |

| 8.6 | Shared values on land use | Culturally shared principles for appropriate land use | 66 |

| 8.7 | Social sanctions | Community-imposed sanctions for violating sustainability norms | 98 |

| 8.8 | Trust in external institutions | Trust in external institutions such as government or NGOs | 93 |

| 9.1 | Agroforestry practices | Land rehabilitation through tree planting and ecological restoration | 93 |

| 9.2 | Climate-resilient agriculture | Farming systems resilient to climate variability and shocks | 74 |

| 9.3 | Cocoa-based rehabilitation models | Agroforestry-based land rehabilitation integrating cocoa crops | 92 |

| 9.4 | Farmer field schools | Field-based learning for sustainable farming among smallholders | 87 |

| 9.5 | Intercropping systems | Combining multiple crops to maximize land productivity | 94 |

| 9.6 | Market access support | Support for marketing and logistics of post-mining agricultural products | 73 |

| 9.7 | Organic certification programs | Programs ensuring organic compliance in production systems | 88 |

| 9.8 | Soil health restoration | Improving the physical, chemical, and biological health of soil | 78 |

| 10.1 | Belief in sustainable agriculture | Belief in farming or ecological alternatives to mining | 59 |

| 10.2 | Economic security perception | Sense of economic security from sustainable land use | 84 |

| 10.3 | Emotional connection to the land | Personal or cultural attachment to land and place | 90 |

| 10.4 | Long-term vision of livelihoods | Future-oriented planning for livelihoods after mining closure | 27 |

| 10.5 | Optimism about post-mining life | Hopefulness and confidence in future land-based outcomes | 84 |

| 10.6 | Perceived value of restoration | Community-perceived importance of restoring degraded land | 90 |

| 10.7 | Willingness to conserve land | Willingness of residents to preserve rehabilitated land | 77 |

| 10.8 | Youth engagement in sustainability | Youth participation and interest in sustainability actions | 80 |

| Total | 7513 |

Appendix C. Environmental Themes and NVivo Coding Map

| # | Environmental Theme/Issue | Addressed Through NVivo Node(s) | Literature Source Type | Linked NVivo Parent Node(s) | Mapped NVivo Node(s) |

| 1 | Soil degradation and rehabilitation | Soil health restoration, Agroforestry practices, Organic certification programs | Sustainable agriculture reports, Soil science in community studies | Agroecological Livelihoods | Agroecological Livelihoods → Soil health restoration |

| 2 | Water management in post-mining areas | Climate-resilient agriculture, Farmer field schools, Market access support | Post-mining recovery planning, Institutional environmental reviews | Agroecological Livelihoods | Agroecological Livelihoods → Climate-resilient agriculture |

| 3 | Ecosystem restoration | Cocoa-based rehabilitation models, Agroecological Livelihoods, Biodiversity values (coded subnode) | NGO project evaluations, agroecology studies | Agroecological Livelihoods, Environmental Preparedness | Agroecological Livelihoods → Cocoa-based rehabilitation models; Environmental Preparedness → Biodiversity protection |

| 4 | Climate resilience | Climate-resilient agriculture, Sustainability belief systems | Resilience literature, institutional adaptation frameworks | Attitude toward Sustainability, Agroecological Livelihoods | Agroecological Livelihoods → Climate-resilient agriculture; Attitude toward Sustainability → Sustainability belief systems |

| 5 | Land use planning | Spatial zoning for post-mining use, Long-term land use strategy | Spatial justice research, participatory planning articles | Land Compensation and Planning | Land Compensation and Planning → Spatial zoning for post-mining use; Long-term land use strategy |

| 6 | Erosion control and revegetation | Revegetation practices (coded under Agroforestry), Soil health restoration | Community forestry and land rehabilitation studies | Agroecological Livelihoods, Environmental Preparedness | Agroecological Livelihoods → Agroforestry practices; Soil health restoration |

| 7 | Risk and disaster preparedness | Institutional trust building, Risk management (cross-coded under Governance Alignment) | Disaster risk management and community preparedness literature | Legitimacy and Governance Alignment | Legitimacy and Governance Alignment → Institutional trust building; Risk and disaster preparedness |

| 8 | Biodiversity protection | Agroforestry practices, Sustainable pest control, Biodiversity restoration (embedded theme) | Biodiversity conservation through sustainable land use | Agroecological Livelihoods, Environmental Preparedness | Agroecological Livelihoods → Sustainable pest control; Environmental Preparedness → Biodiversity protection |

| 9 | Environmental awareness and norms | Norms of environmental care, Intergenerational knowledge, Local leadership influence | Environmental psychology, local norms studies | Norms and Social Trust | Norms and Social Trust → Norms of environmental care; Intergenerational knowledge |

| 10 | Environmental regulation compliance | Compliance with EIA/AMDAL, Regulatory enforcement capacity | Environmental governance and mining law literature | Legitimacy and Governance Alignment | Legitimacy and Governance Alignment → Compliance with EIA/AMDAL; Regulatory enforcement capacity |

References

- Tomassi, A.; Falegnami, A.; Meleo, L.; Romano, E. The greenSCENT competence framework. In The European Green Deal in Education, 1st ed.; McDonagh, S.A., Caforio, A., Pollini, A., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2024; Chapter 2; pp. 8–27. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Suchman, M.C. Managing legitimacy: Strategic and institutional approaches. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 571–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leinfelder, R.R.; Iramina, W.S.; de Eston, S.M. Mining as a tool for reclamation of a degraded area. Rev. Esc. Minas Oura Preto 2015, 68, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Khobragade, K. Impact of mining activity on environment: An overview. Int. J. Sci. Res. Publ. (IJSRP) 2020, 10, 784–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karsadi, K.; Aso, L. Multidimensional Impacts of Nickel Mining Exploitation towards the Lives of the Local Community. J. Ilmu Sos. Dan Hum. 2023, 12, 222–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsaoly, R.M.; Zais, M.; Samiun, M.; Muhammad, N.I.; Kalengkongan, Y.S. Dampak alih fungsi lahan pertanian ke pertambangan terhadap kehidupan sosial ekonomi masyarakat di Desa Lelilef Waibulen Kabupaten Halmahera Tengah. J. Ekon. Pembang. Unkhair 2024, 15, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Putera, A.; Sukotjo, E.; Dharmawati, T.; Mokodompit, E.A. Model of community empowerment based on local wisdom through corporate social responsibility in North Konawe District. Asia Pac. J. Manag. Educ. 2020, 3, 1–10. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/search.Search.html?query=Model+of+community+empowerment+based+on+local+wisdom+through+corporate+social+responsibility+in+North+Konawe+District&type=publication (accessed on 6 June 2025). [CrossRef]

- Saleh, A.; Dalimunthe, A.H. Model of corporate social responsibility (CSR) gold mining for community empowerment Batangtoru District of South Tapanuli in North Sumatra Province. Bp. Int. Res. Crit. Inst.-J. (BIRCI-J.) 2018, 1, 144–152. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/search.Search.html?query=Model+of+Corporate+Social+Responsibility+%28CSR%29+Gold+Mining+for+Community+Empowerment+Batangtoru+District+of+South+Tapanuli+in+North+Sumatra+Province&type=publication (accessed on 30 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Adei, D.; Addei, I.; Kwadjosse, H.A. A study of the effects of mining activities on the health status of people: A case study. Res. J. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2011, 3, 99–104. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/294794859_A_Study_of_the_Effects_of_Mining_Activities_on_the_Health_Status_of_People_A_Case_Study (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- Hu, Q.; Lu, C.; Chen, T.; Chen, W.; Yuan, H.; Zhou, M.; Qiu, Z.; Bao, L. Evaluation and analysis of the gross ecosystem product towards the sustainable development goals: A case study of Fujian Province, China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3925. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/368727147_Evaluation_and_Analysis_of_the_Gross_Ecosystem_Product_towards_the_Sustainable_Development_Goals_A_Case_Study_of_Fujian_Province_China (accessed on 30 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Bhukya, V. Corporate social responsibility practices in the top ten Indian companies and its impact on community development. Int. J. Humanit. Manag. Soc. Sci. (IJ-HuMaSS) 2023, 6, 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewantara Lavinia, R.C. Mechanism implementation of corporate social responsibility by the mining company. WISESA J. Pengabdi. Masy. 2022, 1, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dariah, A.; Abdurachman, A.; Subardja, D. Reclamation of ex-mining land for agricultural extensification. J. Sumberd. Lahan 2012, 4, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Kindangen, J.G.; Kairupan, A.N.; Joseph, G.H.; Rawung, J.B.M.; Indrasti, R. Sustainable agricultural development through agribusiness approach and provision of location specific technology in North Sulawesi. E3S Web Conf. 2023, 444, 01003. Available online: https://www.e3s-conferences.org/articles/e3sconf/abs/2023/81/e3sconf_iconard2023_01003/e3sconf_iconard2023_01003.html (accessed on 30 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Landicho, L.D.; Ramirez, M.A.J.P. Strengthening adaptive capacity of rural farming communities in Southeast Asia: Experiences, best practices and lessons for scaling-up. APN Sci. Bull. 2023, 2023, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adiansyah, J.S.; Sukuryadi, S.; Ariyanto, A.; Nurhayati, N.; Muliatiningsih, M.; Wijaya, A.; Matrani, B.F.A.; Johari, H.I. Pemberdayaan masyarakat lingkar tambang dalam pengolahan limbah organik. J. Pengabdi. Magister Pendidik. IPA 2018, 7, 961–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirshenava, S. Post-mining land-use planning: An integration of mined land suitability assessment and SWOT analysis in Chadormalu iron ore mine of Iran. In Proceedings of the 27th International Mining Congress and Exhibition of Turkey, IMCET 2022, Antalya, Turkey, 22–25 March 2022; pp. 726–741. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/search.Search.html?query=Post-mining+land-use+planning%3A+An+integration+of+mined+land+suitability+assessment+and+SWOT+analysis+in+Chadormalu+iron+ore+mine+of+Iran&type=publication (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- Lockie, S.; Franettovich, M.; Petkova-Timmer, V.; Rolfe, J.; Ivanova, G. Coal mining and the resource community cycle: A longitudinal assessment of the social impacts of the Coppabella coal mine. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2009, 29, 330–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillo, I.; Bilame, O.; Anthony Assenga, E. Corporate social responsibility practices: Insights from North Mara gold mine, Tanzania. Int. J. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2023, 12, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikerd, J.E. The need for a systems approach to sustainable agriculture. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 1993, 46, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayiah, M.; Fayiah, M.S. Long and short term implications of mineral mining operations in Sierra Leone: A review. Nat. Resour. Conserv. Res. 2024, 7, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valle Díaz, F.R.; Apaza-Apaza, O.; Rodriguez-Peceros, R.I.; Huamán-Cuya, A.; Valle-Sherón, J.F.; Luque-Rivera, J.V.; Dávila-Ignacio, C.V.; Chaccara-Huachaca, H. Sustainability of informal artisanal mining in the peruvian andean region. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostetska, K.; Laurinaitis, M.; Savenko, I.; Sedikova, I.; Sylenko, S. Mining management based on inclusive economic approach. E3S Web Conf. 2020, 201, 01009. Available online: https://www.e3s-conferences.org/articles/e3sconf/abs/2020/61/e3sconf_usme2020_01009/e3sconf_usme2020_01009.html (accessed on 30 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Paterson, B.L.; Dubouloz, C.-J.; Chevrier, J.; Ashe, B.; King, J.; Moldoveanu, M. Conducting qualitative metasynthesis research: Insights from a metasynthesis project. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2009, 8, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bainton, N.; Kemp, D.; Lèbre, E.; Owen, J.R.; Marston, G. The energy-extractives nexus and the just transition. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 29, 624–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, H.; King, J.C.; Peden, A.E.; Franklin, R.C. Systematic review of the impact of heatwaves on health service demand in Australia. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 960. Available online: https://bmchealthservres.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12913-022-08341-3 (accessed on 30 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Indonesian Mining Institute. Report on Indonesia Mining Sector Diagnostic; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/704581575962514304/pdf/Report-on-Indonesia-Mining-Sector-Diagnostic.pdf (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- Widiatedja, I.G.N.P. Fragmented Approach to spatial management in Indonesia: When it will be ended? Kertha Patrika 2021, 43, 145–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulistyawan, B.S.; Verweij, P.A.; Boot, R.G.A.; Purwanti, B.; Rumbiak, W.; Wattimena, M.C.; Rahawarin, P.; Adzan, G. Integrating participatory GIS into spatial planning regulation: The case of Merauke District, Papua, Indonesia. Int. J. Commons 2018, 12, 26–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett-Page, E.; Thomas, J. Methods for the synthesis of qualitative research: A critical review. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2009, 9, 59. Available online: https://bmcmedresmethodol.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2288-9-59 (accessed on 30 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Dhuria, D.; Chetty, P. Explaining Validity and Reliability of Qualitative Data in Nvivo. Project Guru. Available online: https://www.projectguru.in/explaining-validity-reliability-qualitative-data-nvivo/ (accessed on 31 May 2025).

- Song, F.; Parekh, S.; Hooper, L.; Loke, Y.; Ryder, J.; Sutton, A.; Hing, C.; Kwok, C.; Pang, C.; Harvey, I. Dissemination and publication of research findings: An updated review of related biases. Health Technol. Assess. 2010, 14, 1–193. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/41561626_Dissemination_and_publication_of_research_findings_An_updated_review_of_related_biases (accessed on 30 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Olmos-Vega, F.M.; Stalmeijer, R.E.; Varpio, L.; Kahlke, R. A practical guide to reflexivity in qualitative research: AMEE Guide No. 149. Med. Teach. 2022, 45, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Poth, C.N. Qualitative Inquiry & Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches, 4th ed.; Sage Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2018; Available online: https://revistapsicologia.org/public/formato/cuali2.pdf (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- UNEP. Making Peace with Nature: A Scientific Blueprint to Tackle the Climate, Biodiversity and Pollution Emergencies; United Nations: Nairobi, Kenya, 2021; Available online: https://www.unep.org/resources/making-peace-nature (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- Montenegro de Wit, M. What grows from a pandemic? Toward an abolitionist agroecology. J. Peasant Stud. 2020, 48, 99–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, J.D.; Lafortune, G.; Kroll, C.; Fuller, G.; Woelm, F. Sustainable Development Report 2022 Sustainable Development Report 2022 From Crisis to Sustainable Development: The SDG as Roadmap to 2030 and Beyond; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2022; Available online: https://s3.amazonaws.com/sustainabledevelopment.report/2022/2022-sustainable-development-report.pdf (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- BPS-Statistics Indonesia. Keadaan Angkatan Kerja di Indonesia Agustus 2023 (Labor Force Situation in Indonesia August 2023); BPS-Statistics Indonesia: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2023; Available online: https://www.bps.go.id/id/publication/2023/12/08/f8c567805aa8a6977bd4594a/keadaan-angkatan-kerja-di-indonesia-agustus-2023.html (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- Afrizal, A.; Berenschot, W. Resolving Land Conflicts in Indonesia. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Southeast Asia 2020, 176, 561–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soja, E.W. Seeking Spatial Justice: An Innovative New Way of Understanding and Changing the Unjust Geographies in Which We Live; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2010; Available online: https://www.upress.umn.edu/9780816666683/seeking-spatial-justice/ (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- Down to Earth. Business, Human Rights and Climate in the UK-Indonesia Relationship. Down to Earth: International Campaign for Ecological Justice in Indonesia. Available online: https://www.downtoearth-indonesia.org/story/business-human-rights-and-climate-uk-indonesia-relationship (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- Wily, L.A. The Tragedy of Public Lands: The Fate of the Commons Under Global Commerical Pressure; International Land Coalition: Rome, Italy, 2011; Available online: https://www.iccaconsortium.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/legal-example-the-tragedy-of-public-lands-2011.pdf (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- Larson, A.M. Tenure Rights and Access to Forests: A Training Manual for Research Issues; Center for International Forestry Research: Bogor, Indonesia, 2012; Available online: https://www.cifor-icraf.org/publications/pdf_files/Books/BLarson1201.pdf (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- Siahaan, J.R.; Pagalung, G.; Demmallino, E.B.; Saleng, A.; Sulaiman, A.A.; Nagu, N. A TBL Performance Measurement Model for the Sustainability of Post-Mining Landscapes of Indonesia; Hasanuddin University: Makassar, Indonesia, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandagie, W.C.; Susanto, K.P.; Endri, E.; Wiwaha, A. Corporate governance, financial performance and sustainability disclosure: Evidence from Indonesian energy companies. Uncertain Supply Chain Manag. 2024, 12, 1791–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Feasibility Study: Systematic Disclosures of Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) Data in Indonesia; World Bank: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2021; Available online: https://portaldataekstraktif.esdm.go.id/storage/post-file/20240614160358/210729%20-%20mainstreaming%20feasibility%20summary%20-%20msg%20meeting.pdf (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- UNDP. Building Resilience Through Livelihoods and Economic Recovery; United Nations Development Programme: New York, NY, USA, 2022; Available online: https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/2023-06/livelihoods_and_economic_recovery.pdf (accessed on 2 May 2025).

- Kementerian ESDM. Laporan Kinerja Kementerian Energi dan Sumber Daya Mineral Republik Indonesia Tahun 2023; Kementerian ESDM: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2024; Available online: https://www.esdm.go.id/assets/media/content/content-laporan-kinerja-kementerian-esdm-tahun-2023.pdf (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- Zulpahmi, L.I.; Shafrullah, F.; Wibowo, B.P.; Sumardi, A.W.N.; Fadhilah, A.S.H. Enhancing corporate social responsibility (CSR) transparency: The role of corporate governance in Indonesia mining sector. Libr. Prog. Int. 2024, 44, 2140–2156. [Google Scholar]

- Siahaan, J.R.; Pagalung, G.; Demmallino, E.B.; Saleng, A.; Sulaiman, A.A.; Nagu, N. A Community Development Performance Model for the Sustainability of Post-Mining Landscapes of Indonesia; Hasanuddin University: Makassar, Indonesia, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. The State of Food and Agriculture 2020; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuliani, E.L.; de Groot, W.T.; Knippenberg, L.; Bakara, D.O. Forest or oil palm plantation? Interpretation of local responses to the oil palm promises in Kalimantan, Indonesia. Land Use Policy 2020, 96, 104616. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0264837718319963 (accessed on 30 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Understanding Institutional Diversity; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, R.; Franks, D. Costs of Company-Community Conflict in the Extractive Sector; Cambridge: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014; Available online: https://www.csrm.uq.edu.au/media/docs/603/Costs_of_Conflict_Davis-Franks.pdf (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- Owen, J.R.; Kemp, D. Social licence and mining: A critical perspective. Resour. Policy 2013, 38, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasetio, J.E.; Sabihaini, S.; Astuti, W.T.; Susanto, A.A.; Pradessa, S.G. Integration of CSR and SDGs in realizing village values Sambirejo, Sleman Regency. SHS Web Conf. 2025, 212, 04001. Available online: https://www.shs-conferences.org/articles/shsconf/abs/2025/03/shsconf_icarsess2024_04001/shsconf_icarsess2024_04001.html (accessed on 30 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Bappenas. Pedoman Teknis Penyusunan Rencana Aksi Tujuan Pembangunan Berkelanjutan (TPB)/Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs); Perhimpunan Filantropi Indonesia: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2020; Available online: https://filantropi.or.id/repositori/pedoman-teknis-penyusunan-rencana-aksi-tujuan-pembangunan-berkelanjutan-tpb-sustainable-development-goals-sdgs/ (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. Psihol. Suspìlʹstvo 2024, 90, 63–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugroho, A.P.; Hidayat, A.; Kusuma, H. The influence of religiosity and self-efficacy on the saving behavior of the slamic banks. Banks Bank. Syst. 2017, 12, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kementerian Pertanian. Laporan Tahunan; Kementerian Pertanian: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kementerian Pertanian. Statistik Ketenagakerjaan Sektor Pertanian; Kementerian Pertanian: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ashurov, S.; Musse, O.S.H.; Abdelhak, T. Evaluating corporate social responsibility in achieving sustainable development and social welfare. BRICS J. Econ. 2024, 5, 77–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lassa, J.A.; Nappoe, G.E.; Sulistyo, S.B. Creating an institutional ecosystem for cash transfer programming in post-disaster settings: A Case from Indonesia. Gen. Econ. 2022, 1–21. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/358520276_Creating_an_institutional_ecosystem_for_cash_transfer_programming_Lessons_from_post-disaster_governance_in_Indonesia (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- Sinaga, R.R. Corporate social responsibility as strategy in Indonesia context. SAKI: Studi Akunt. Dan Keuang. Indones. 2024, 7, 139–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahim, A.; Malik, A.; Hastuti, D.R.D.; Sabar, W.; Irwandi, I. Fishermen’s exchange rate on capture fisheries business in the coastal area. In Research Trends in Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences; Sundaray, J.K., Ed.; AkiNik Publications: New Delhi, India, 2023; Volume 16, Chapter 2; pp. 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putu, S.D.I.G.; Majid, M.N. Optimising green industry development to strengthen the national economy. J. Lemhannas RI 2024, 12, 373–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obidzinski, K.; Takahashi, I.; Dermawan, A.; Komarudin, H.; Andrianto, A. Can large scale land acquisition for agro-development in Indonesia be managed sustainably? Land Use Policy 2013, 30, 952–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qonita, F. Dynamic governance in bureaucratic reform: A case study of Dispendukcapil Surabaya. J. Mengkaji Indones. 2024, 3, 243–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, H.; Fachruddin, S. Regulation Model of Southeast Sulawesi Provincial Government on community empowerment and development through corporate social and responsibility (CSR) in mining sector. Int. J. Qual. Res. 2022, 1, 164–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rela, I.Z.; Firihu, M.Z.; Awang, A.H.; Iswandi, M.; Malek, J.A.; Nikoyan, A.; Nalefo, L.; Batoa, H.; Salahuddin, S. Formation of farming community resilience models for sustainable agricultural development at the mining neighborhood in Southeast Sulawesi Indonesia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puslitkoka. Penandatanganan MOU Pengembangan Kakao di Daerah Tambang. Puslitkoka. Available online: https://iccri.net/penandatanganan-mou-antara-puslitkoka-pt-rpn-dan-pt-berau-coal-untuk-pengembangan-kakao-di-daerah-tambang/ (accessed on 13 May 2025).

- Savirani, A.; Wardhani, I.S. Local social movements and local democracy: Tin and gold mining in Indonesia. Taylor Fr. Publ. Cover J. Homepage S. East Asia Res. 2022, 30, 489–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darmawan, L.; Jamil, R.; Rees, C.J. Human resource management and corporate social responsibility: A case study of a vocational and education training (VET) programme in Indonesia. Ind. Commer. Train. 2023, 55, 457–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resnawaty, R.; Rivani, R. Empowered community vs dependent community: Corporate social responsibility (CSR) implications by mining companies in South Sumatra Province. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 2017, 8, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, W. Ketika Tren Kakao di SULAWESI Gerus Pertanian Tanaman Pangan. Mongabay (Situs Berita Lingkungan). Available online: https://www.mongabay.co.id/2022/01/19/ketika-tren-kakao-di-sulawesi-gerus-pertanian-tanaman-pangan/ (accessed on 13 May 2025).

- Sitepu, M.E.; Hariandi, D.; Septirosya, T. Effectiveness test of local arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) and cocoa waste compost on the growth of cocoa seedlings (Theobroma cacao L.) in former mining sites. JERAMI Indones. J. Crop Sci. 2024, 6, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosmana, A.; Sakrabani, R.; Sjam, S.; Nasaruddin, N.; Asman, A.; Pandin, B.Y.S. Plant residue based-composts applied in combinationwith trichoderma asperellum improve cacao seedling growth in soil derived from nickel mine area. J. Anim. Plant Sci. 2019, 29, 291–298. Available online: http://www.thejaps.org.pk/docs/V-29-01/34.pdf (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- Mirasari, R. Pemanfaatan rumput sebagai kompos untuk kesuburan tanah bekas tambang batu dengan uji bibit tanaman kakao (Theobroma cacao L.). Bul. Poltanesa 2020, 21, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeweld, W.; Van Huylenbroeck, G.; Tesfay, G.; Speelman, S. Smallholder farmers’ behavioural intentions towards sustainable agricultural practices. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 187, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danielsen, F.; Eicken, H.; Funder, M.; Johnson, N.; Lee, O.; Theilade, I.; Argyriou, D.; Burgess, N.D. Community monitoring of natural resource systems and the environment. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2022, 47, 637–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofosu-Ampong, K.; Abera, W.; Müller, A.; Adjei-Nsiah, S.; Boateng, R.; Acheampong, B. Framing behaviour change for sustainable agriculture: Themes, approaches, and future directions. Farming Syst. 2024, 3, 100123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratama, N.S.; Lindrianasari, L.; Saipuddin, U. Role of Benefits, Impacts and Community Trust in Predicting Mining Operational Acceptance in the Community. Int. J. Innov. Educ. Res. 2019, 7, 236–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clodoveo Simona, M.L.G.; Filomena, C. The cocoa value chain: From nutraceutical properties to sustainability issues. A focus on fair trade in Italy. Preprint. 2024. 2024010264. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/377225339_The_Cocoa_Value_Chain_From_Nutraceutical_Properties_to_Sustainability_Issues_A_Focus_on_Fair_Trade_in_Italy (accessed on 30 April 2024).

- Prasetyawati, T.; Al-Habib, G.S.; Mukhtaruddin, M. Corporate social responsibility (CSR): Insights from a systematic literature review. Int. J. Educ. Soc. Sci. Res. 2024, 3, 226–237. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/386748000_Corporate_Social_Responsibility_CSR_Insights_From_A_Systematic_Literature_Review (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- Santoso, S.; Kasih, E.W.; Saputra, R.M. Analysis of implemented policy strategies and innovations in legal management of natural resources and renewable energy in Indonesia. J. Ris. Dan Inov. Manaj. 2023, 1, 306–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putra, R.E.; Syafiola, M.F. Corporate social responsibility and coastal community transformation: A structuration perspective on livelihood diversification and environmental resilience in Indonesia. Society 2025, 13, 648–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siahaan, J.R.; Pagalung, G.; Demmallino, E.B.; Saleng, A.; Sulaiman, A.A.; Nagu, N. A Transformation-Readiness Model for the Sustainability of Post-Mining Landscapes of Indonesia; Hasanuddin University: Makassar, Indonesia, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Sukanteri, N.P.; Lestari, P.F.K.; Yuniti, I.G.A.D.; Tamba, I.M. Policy and competitiveness of integrated agricultural-based technology for cocoa production in Indonesia: Application of a policy analysis matrix. Rev. Gest. Soc. E Ambient. 2024, 18, e06441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wulandari, D.; Agus, C.; Rosita, R.; Mansur, I.; Maulana, A.F. Impact of tin mining on soil physio-chemical properties in Bangka, Indonesia. J. Sains Dan Teknol. Lingkung. 2022, 14, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, Z.A.; Kunasekaran, P.; Alam, M. The role of social capital and social media in tourism development towards the wellbeing of the Mah Meri community in Carey Island, Malaysia. Pertanika J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2025, 33, 113–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parent Node | Child Node | Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| Motivation and Empowerment | Access to microfinance, Community-led initiatives, Decision-making autonomy, Local entrepreneurship incentives, Psychological resilience, Recognition and reward mechanisms, Training and skills development, Visioning and goal setting | 913 |

| Stakeholder Engagement | Dialogues with Indigenous communities, Engagement mapping, Farmer cooperative role, Gender-inclusive representation, Grievance redressal systems, Multi-stakeholder forums, NGO involvement, Participation in planning | 818 |

| Legitimacy Theory Application | Cognitive legitimacy patterns, Institutional credibility, Legitimacy crises, Moral legitimacy indicators, Perception of fairness, Pragmatic legitimacy cues, Reputation management, Role of transparency | 808 |

| CSR Co-Financing Mechanism | Allocation of CSR funds, Cross-sector CSR alignment, CSR for livelihood transition, CSR reporting standards, Linking CSR to SDGs, Monitoring CSR outcomes, Multi-year budgeting schemes, Public-private partnerships | 786 |

| Land Compensation and Planning | Conflict resolution over land, Customary land rights recognition, Land asset valuation, Legal harmonization for land status, Long-term land use strategy, Participatory land mapping, Resettlement planning, Spatial zoning for post-mining use | 766 |

| Stakeholder Theory Application | Balancing stakeholder claims, Conflict mediation strategies, Institutional responsiveness, Managing stakeholder expectations, Power–legitimacy–urgency typology, Salience-based prioritization, Stakeholder dialogue frameworks, Stakeholder mapping tools | 747 |

| Legitimacy and Governance Alignment | Anti-corruption safeguards, Community consultation mechanisms, Compliance with EIA or AMDAL, Institutional trust building, Policy coherence across agencies, Regulatory enforcement capacity, Role of local government, Transparent permitting process | 711 |

| Norms and Social Trust | Community rule adherence, Intergenerational knowledge, Local leadership influence, Norms of environmental care, Reciprocity in group behavior, Shared values on land use, Social sanctions, Trust in external institutions | 694 |

| Agroecological Livelihoods | Agroforestry practices, Climate-resilient agriculture, Cocoa-based rehabilitation models, Farmer field schools, Intercropping systems Market access support, Organic certification programs, Soil health restoration | 679 |

| Attitude toward Sustainability | Belief in sustainable agriculture, Economic security perception, Emotional connection to land, Long-term vision of livelihoods, Optimism about post-mining life, Perceived value of restoration, Willingness to conserve land, Youth engagement in sustainability | 591 |

| # | Institutional Theme | Observed Issue | Real-World Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Land Compensation and Planning | Unclear land status and elite-dominated compensation processes. | In Southeast Sulawesi, delayed compensation led to protests from landowners excluded from formal mapping. |

| 2 | Legitimacy and Governance Alignment | Regulatory misalignment between national and local governance. | In Morowali, communities reported overlapping licenses issued without public consultation. |

| 3 | CSR Co-Financing Mechanisms | CSR used more for image than co-financed development. | In Kolaka, CSR funds were used to build unutilized infrastructure without stakeholder input. |

| 4 | Agroecological Livelihoods | Pilot programs lack institutional coordination for scale-up. | In Central Sulawesi, cacao programs stalled due to poor coordination between environment and agriculture ministries. |

| # | Behavioral Theme | Observed Issue | Real-World Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Attitude Toward Sustainability | Skepticism toward sustainability due to focus on short-term economic gain. | In Central Sulawesi, farmers questioned the value of replanting degraded land without secure access to markets. |

| 2 | Norms and Social Trust | Erosion of trust in post-mining areas like Morowali due to unfulfilled promises. | In Morowali, multiple villages refused CSR aid after prior projects failed to deliver promised outcomes. |

| 3 | Stakeholder Engagement | Tokenistic participation in CSR planning processes; elite capture reported. | In Kolaka, CSR forums were attended mainly by subdistrict leaders and lacked farmer representation. |

| 4 | Motivation and Empowerment | Decline in motivation where training/support was inconsistent. | In South Konawe, empowerment levels rose when cacao cooperatives received government extension support. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Siahaan, J.R.; Pagalung, G.; Demmallino, E.B.; Saleng, A.; Sulaiman, A.A.; Nagu, N. Reframing Sustainability in Post-Mining Landscapes: A Foundational Framework for Institutional and Behavioral Integration in Indonesia. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5278. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125278

Siahaan JR, Pagalung G, Demmallino EB, Saleng A, Sulaiman AA, Nagu N. Reframing Sustainability in Post-Mining Landscapes: A Foundational Framework for Institutional and Behavioral Integration in Indonesia. Sustainability. 2025; 17(12):5278. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125278

Chicago/Turabian StyleSiahaan, Justan Riduan, Gagaring Pagalung, Eymal Bahsar Demmallino, Abrar Saleng, Andi Amran Sulaiman, and Nadhirah Nagu. 2025. "Reframing Sustainability in Post-Mining Landscapes: A Foundational Framework for Institutional and Behavioral Integration in Indonesia" Sustainability 17, no. 12: 5278. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125278

APA StyleSiahaan, J. R., Pagalung, G., Demmallino, E. B., Saleng, A., Sulaiman, A. A., & Nagu, N. (2025). Reframing Sustainability in Post-Mining Landscapes: A Foundational Framework for Institutional and Behavioral Integration in Indonesia. Sustainability, 17(12), 5278. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125278