Income and Subjective Well-Being: The Importance of Index Choice for Sustainable Economic Development

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature on Differences Among SWB Measures

3. Methods

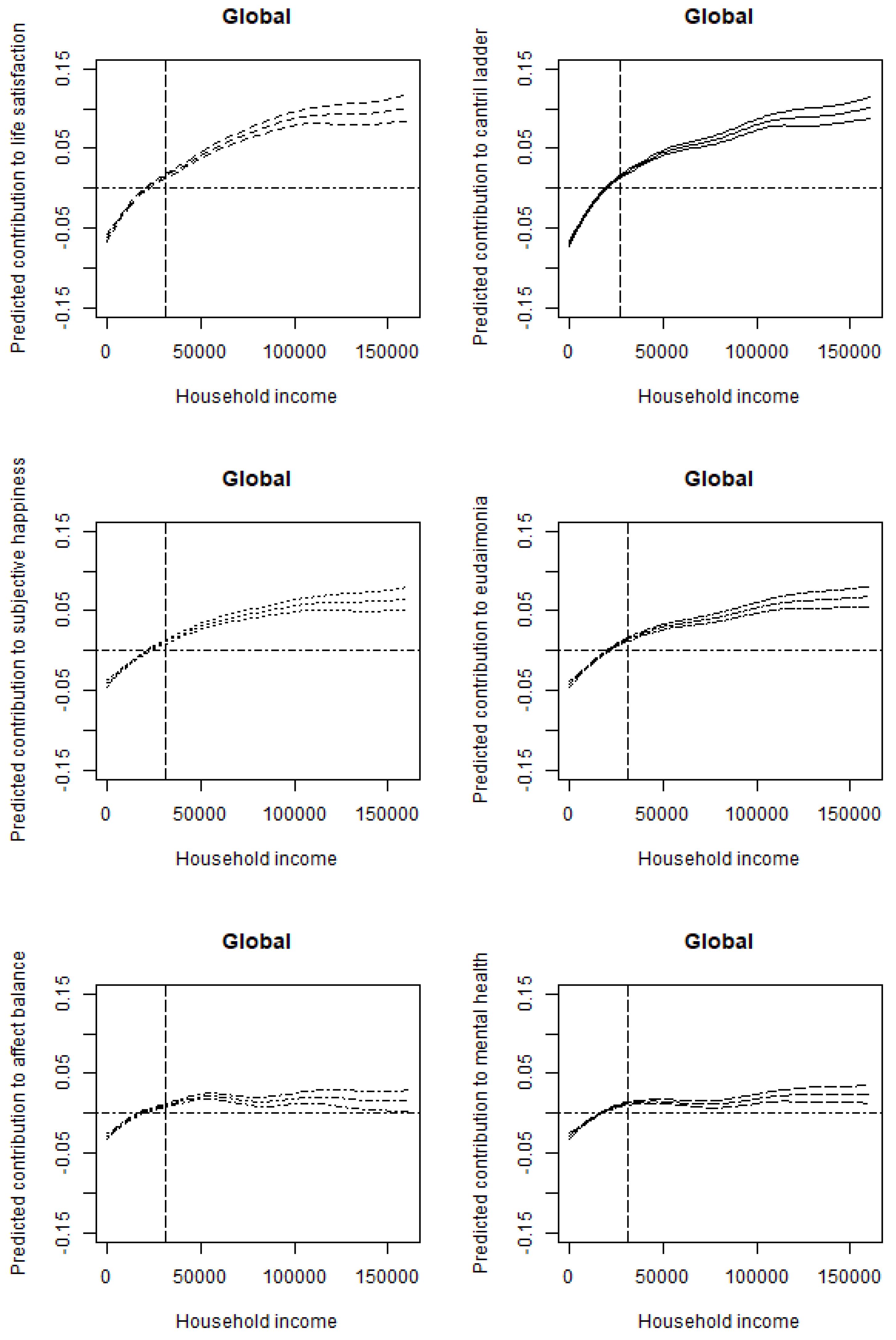

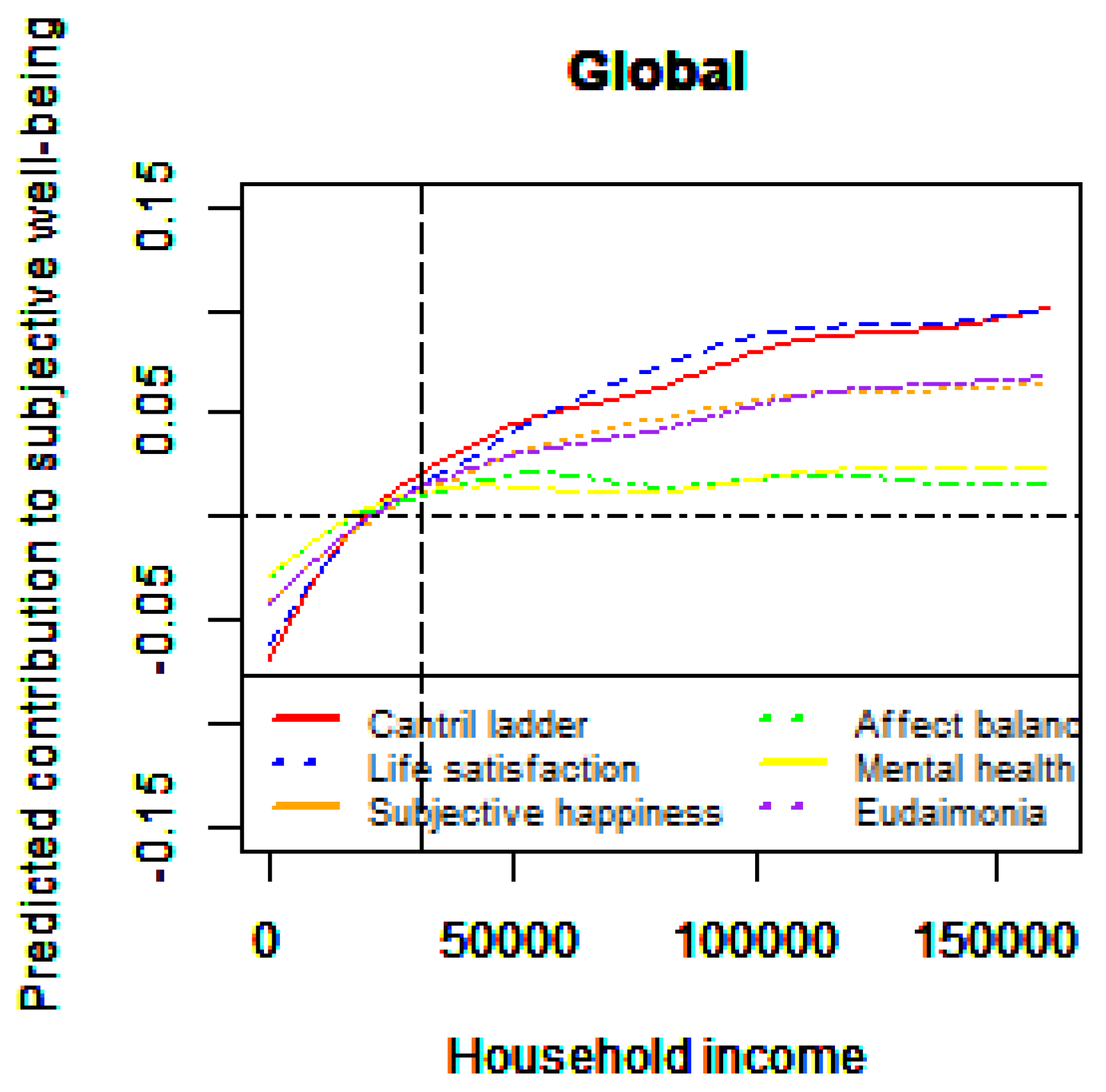

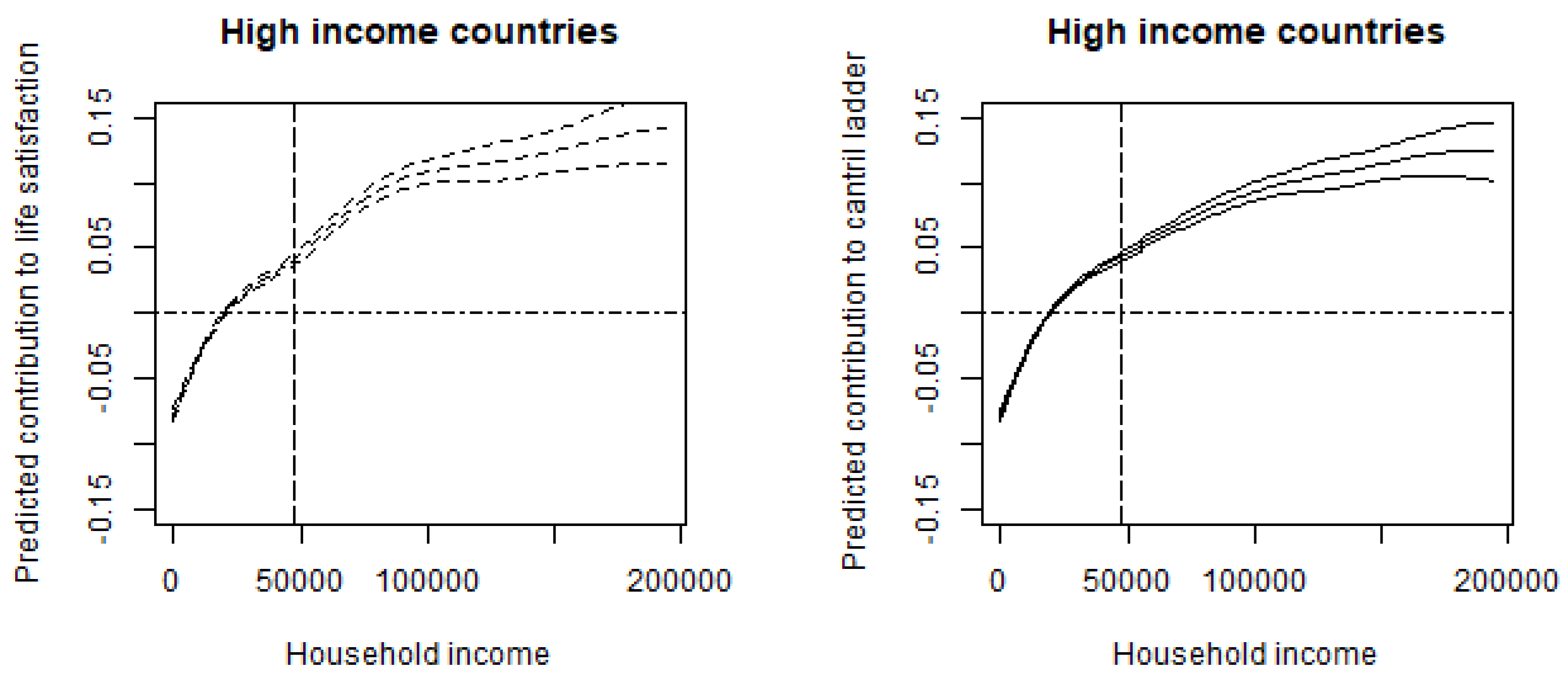

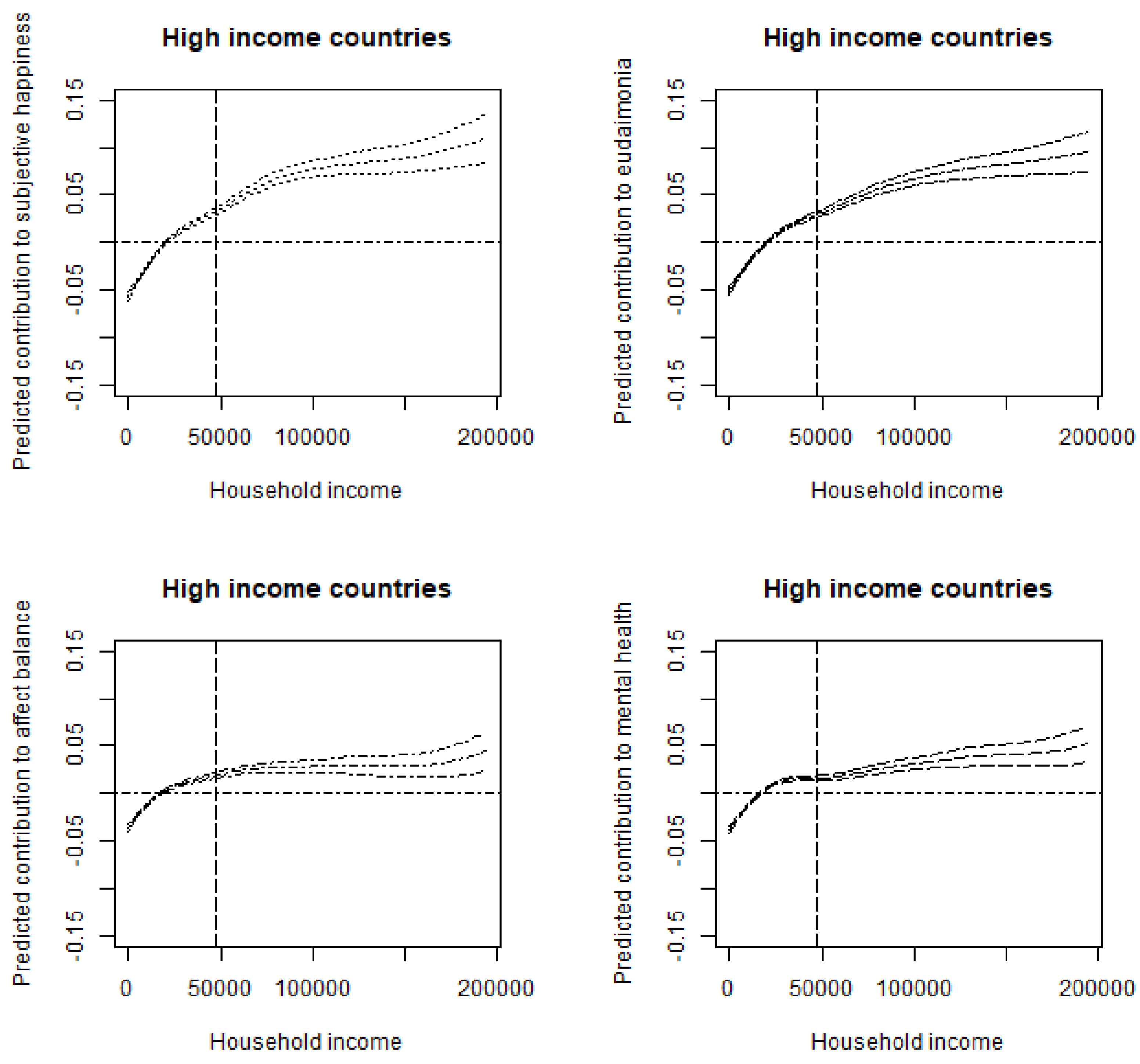

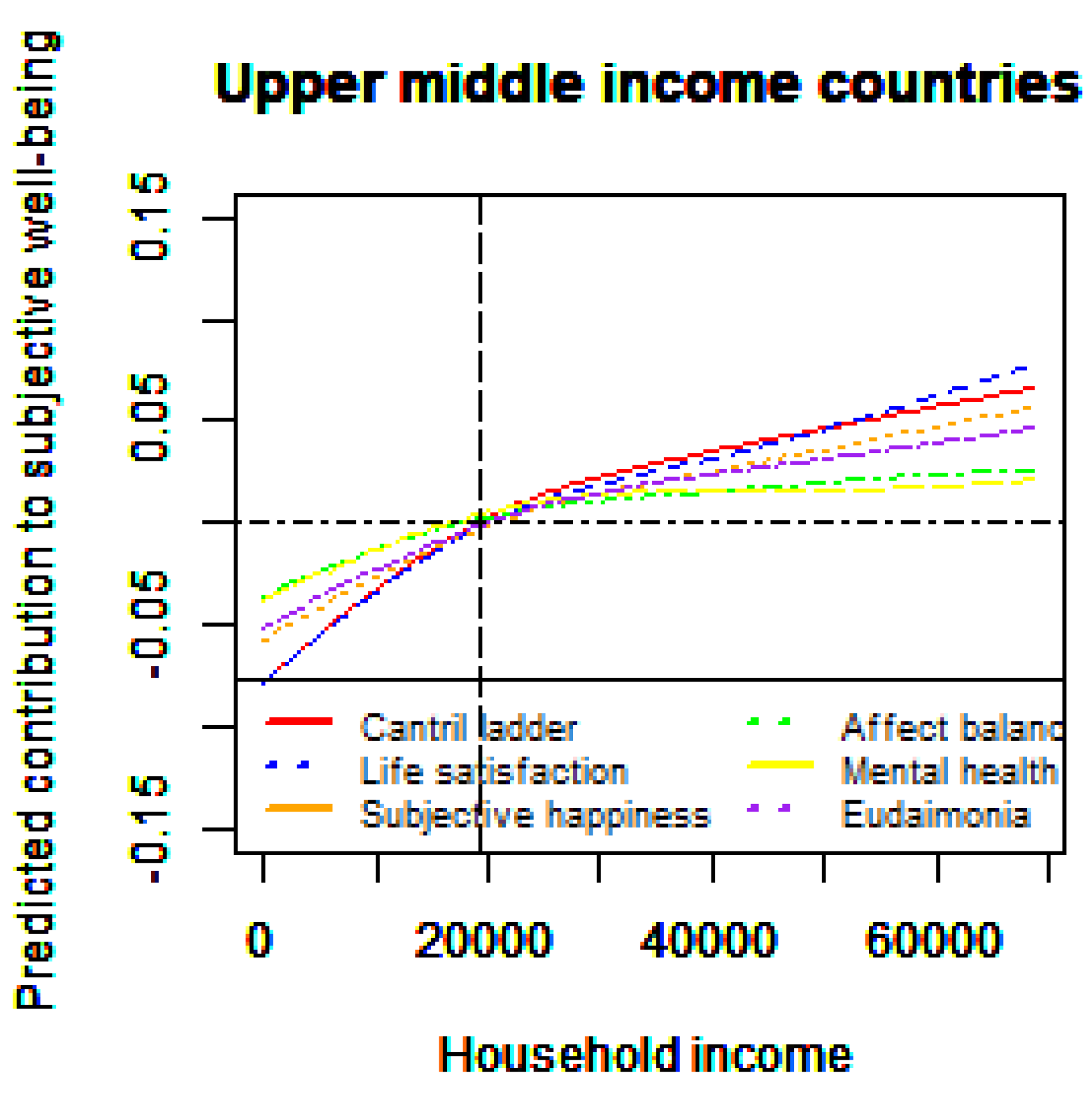

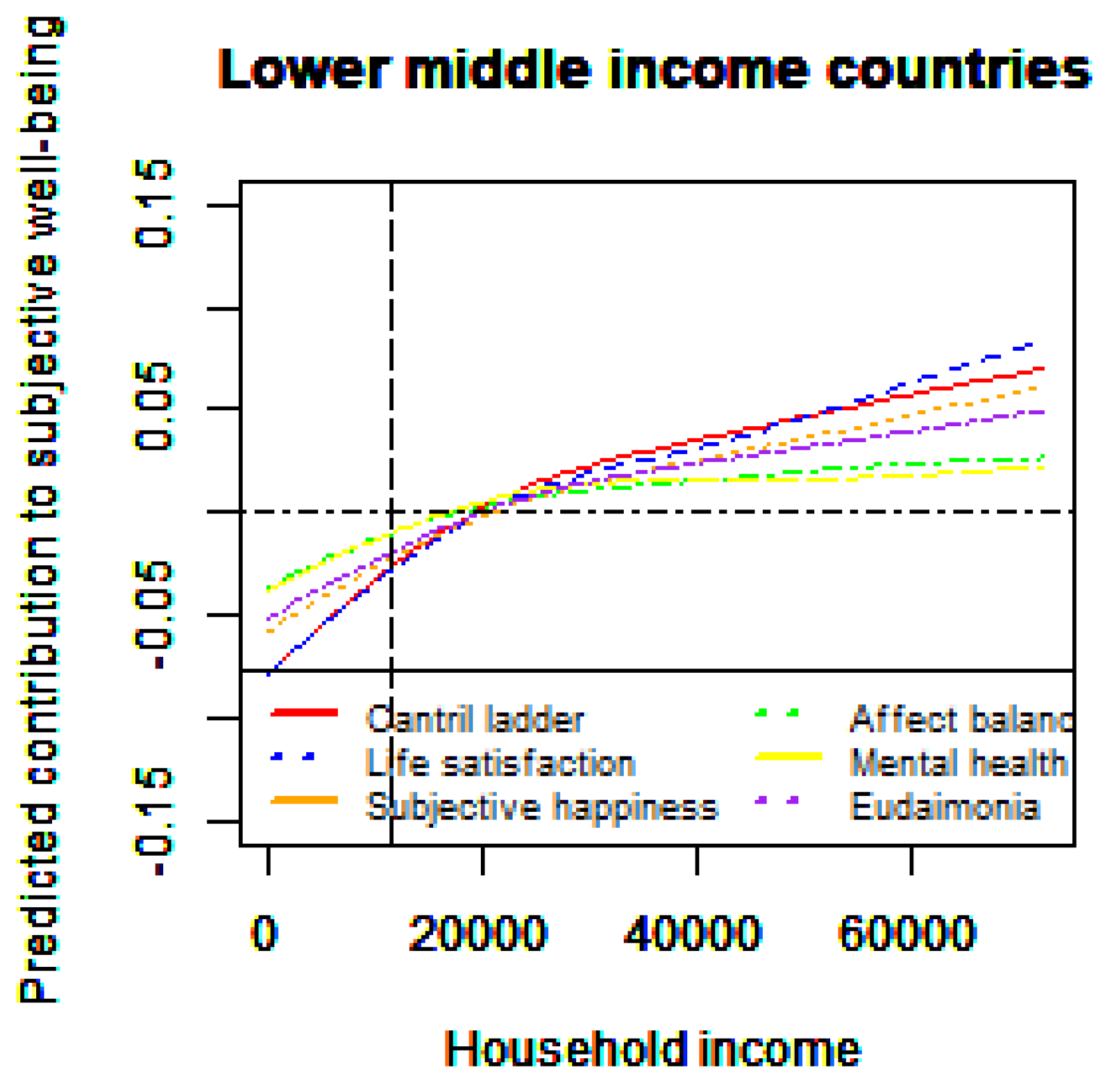

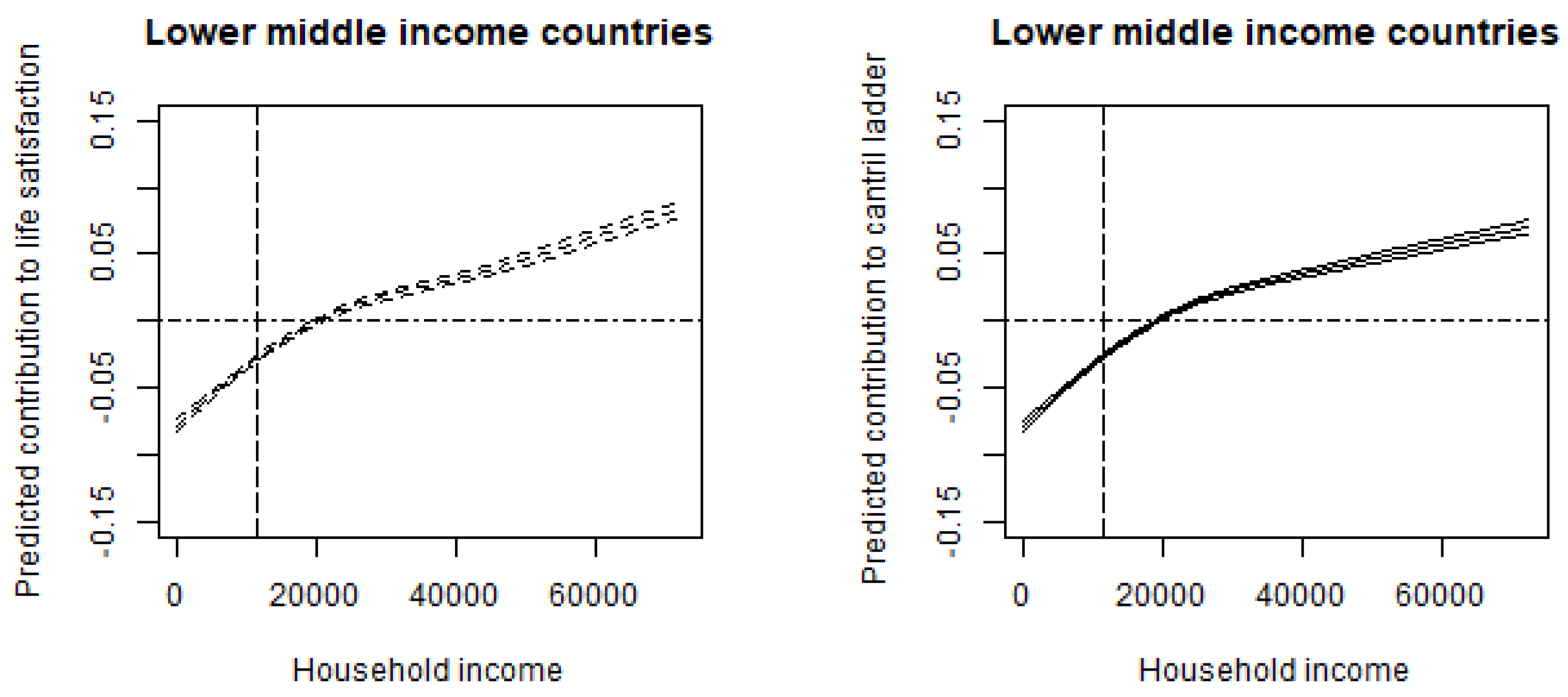

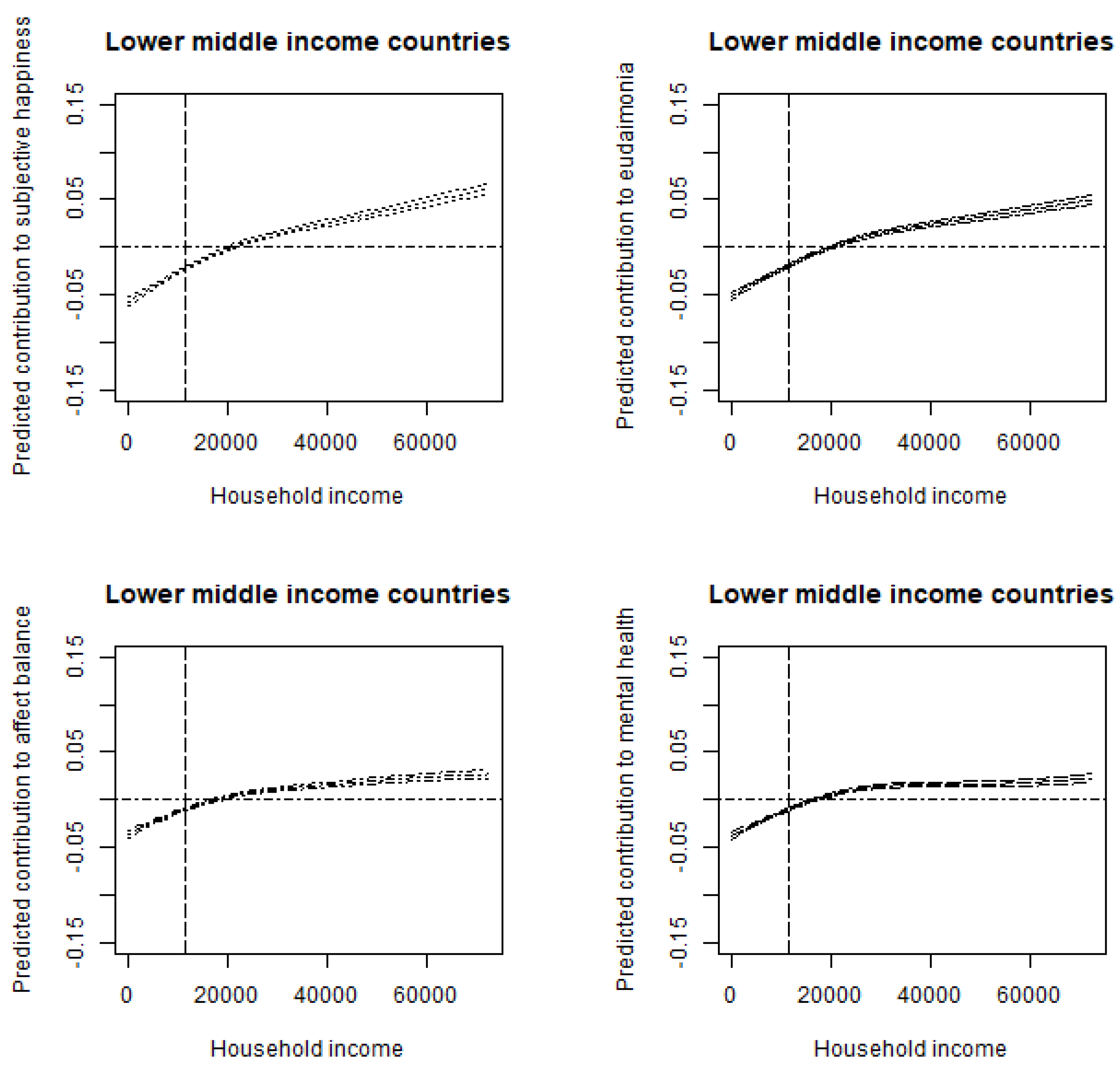

4. Results

5. Robustness

5.1. Robustness: Additional Control Variables

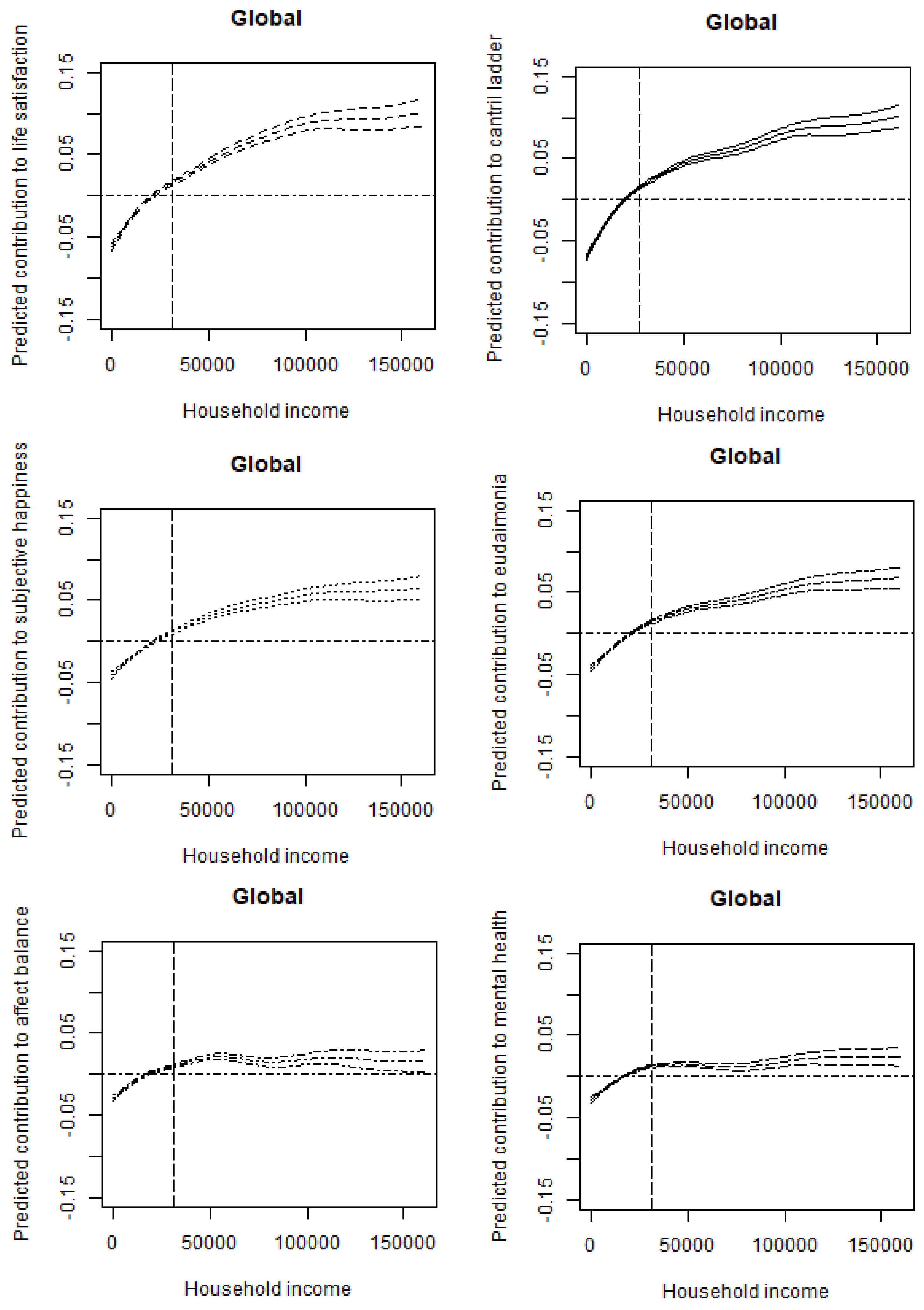

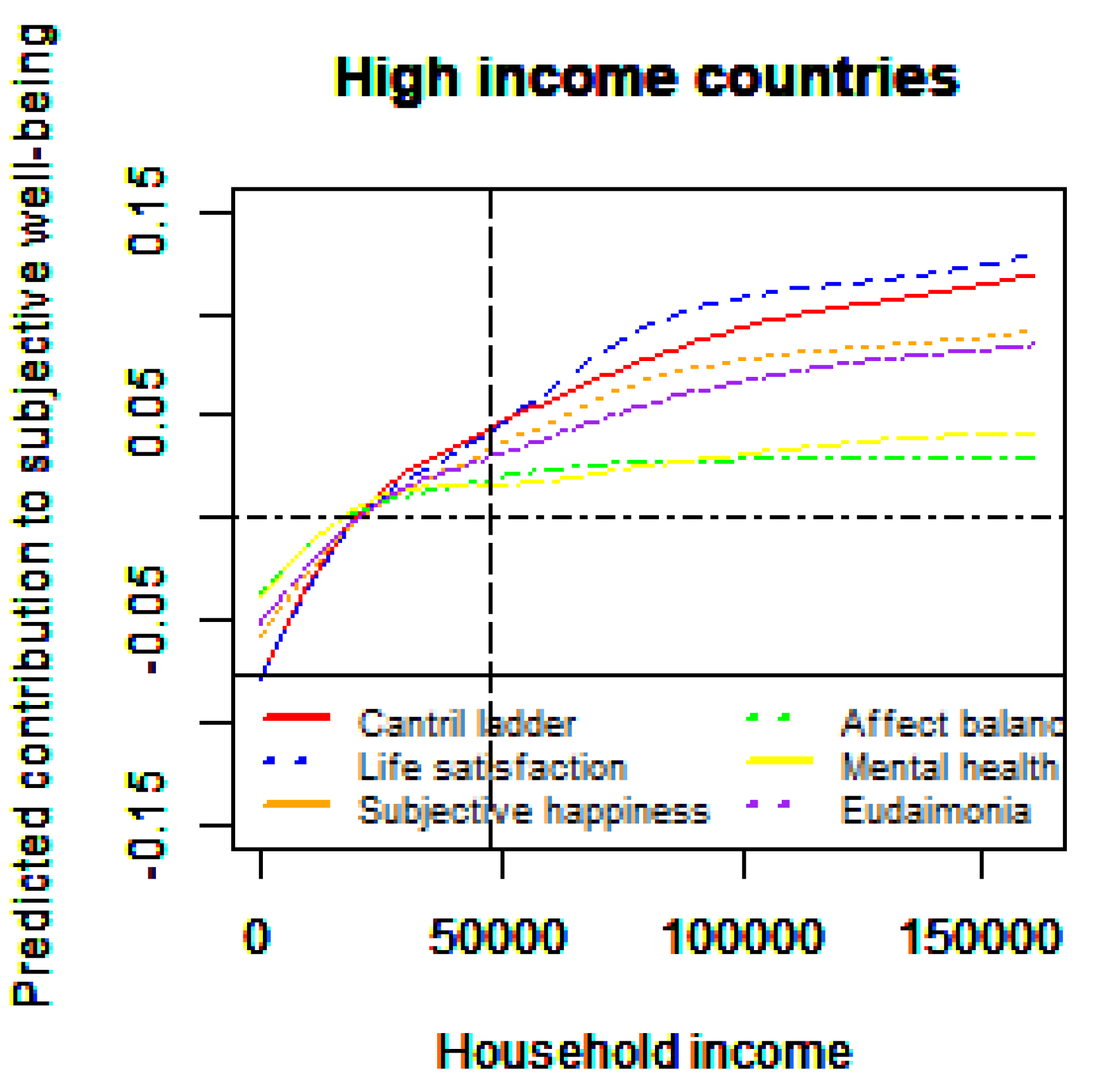

5.2. Robustness: Sub-Samples

6. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Country * | Survey Period | |

|---|---|---|

| Australia | 10 February 2016 | 22 February 2016 |

| Sweden | 31 August 2016 | 12 September 2016 |

| Canada | 1 September 2016 | 13 September 2016 |

| United States | 16 August 2016 | 28 August 2016 |

| Netherlands | 29 August 2016 | 10 September 2016 |

| Germany | 26 August 2016 | 7 September 2016 |

| United Kingdom | 16 August 2016 | 28 August 2016 |

| France | 26 August 2016 | 7 September 2016 |

| Japan | 14 July 2015 | 5 August 2015 |

| Italy | 29 August 2016 | 10 September 2016 |

| Spain | 26 August 2016 | 7 September 2016 |

| Greece | 31 August 2016 | 12 September 2016 |

| Czech Republic | 8 March 2017 | 16 March 2017 |

| Poland | 8 March 2017 | 17 March 2017 |

| Chile | 24 July 2015 | 28 July 2015 |

| Venezuela | 24 July 2015 | 5 August 2015 |

| Russia | 31 August 2015 | 14 September 2015 |

| Malaysia | 23 July 2015 | 29 July 2015 |

| Brazil | 23 July 2015 | 26 July 2015 |

| Mexico | 24 July 2015 | 27 July 2015 |

| Romania | 8 March 2017 | 18 March 2017 |

| China | 12 January 2016 | 29 February 2016 |

| Colombia | 24 July 2015 | 27 July 2015 |

| Thailand | 18 July 2015 | 23 July 2015 |

| South Africa | 15 July 2015 | 23 July 2015 |

| Mongolia | 19 August 2015 | 3 September 2015 |

| Sri Lanka | 9 March 2017 | 30 March 2017 |

| Philippines | 15 July 2015 | 22 July 2015 |

| Egypt | 14 September 2015 | 27 October 2015 |

| Vietnam | 18 July 2015 | 28 July 2015 |

| India | 25 July 2015 | 11 August 2015 |

| Myanmar | 6 July 2015 | 10 August 2015 |

| Country * | GNI per Capita, Calculated Using the World Bank Atlas Method (Current USD) in 2015 | Gallup Self-Reported Median Household Income [USD] in 2013 | Our Survey Data: ANNUAL Household Income (USD) (Average) | Our Survey Data: ANNUAL Household Income (USD) (Median) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High-Income Economies (GNI per capita ≥ USD 12,476) | Australia | 60,050 | 46,555 | 56,011 | 47,769 |

| Sweden | 57,900 | 50,514 | 51,956 | 43,295 | |

| Canada | 57,250 | 41,280 | 48,783 | 41,164 | |

| United States | 55,980 | 43,585 | 60,126 | 45,000 | |

| Netherlands | 48,850 | 38,584 | 44,496 | 39,093 | |

| Germany | 45,790 | 33,333 | 45,488 | 39,093 | |

| United Kingdom | 43,700 | 31,617 | 53,748 | 40,191 | |

| France | 40,710 | 31,112 | 41,092 | 39,093 | |

| Japan | 38,840 | 33,822 | 50,899 | 49,585 | |

| Italy | 32,830 | 20,085 | 40,641 | 27,924 | |

| Spain | 28,380 | 21,959 | 37,593 | 27,924 | |

| Greece | 20,270 | 17,777 | 19,587 | 16,754 | |

| Czech Republic | 18,150 | 22,913 | 15,166 | 12,716 | |

| Poland | 13,310 | 15,338 | 16,821 | 7963 | |

| Upper Middle-Income Economies (GNI per capita = USD 4036–USD 12,475) | Chile | 14,100 ** | 8098 | 16,013 | 11,462 |

| Venezuela | 11,780 *** | 11,239 | 34,088 | 23,841 | |

| Russia | 11,450 | 11,724 | 11,531 | 9782 | |

| Malaysia | 10,570 | 11,207 | 18,708 | 16,894 | |

| Brazil | 9990 | 7522 | 15,103 | 9006 | |

| Mexico | 9710 | 11,680 | 12,281 | 9445 | |

| Romania | 9510 | 7322 | 15,799 | 6244 | |

| China | 7900 | 6180 | 20,357 | 17,481 | |

| Colombia | 7140 | 6544 | 10,833 | 8739 | |

| Thailand | 5720 | 7029 | 17,744 | 12,263 | |

| Lower Middle-Income Economies (GNI per capita = USD 1026–USD 4035) | South Africa | 6080 **** | 5217 | 21,803 | 16,448 |

| Mongolia | 3870 | 5922 | 5403 | 4758 | |

| Sri Lanka | 3800 | 3242 | 4121 | 3749 | |

| Philippines | 3550 | 2401 | 11,318 | 9228 | |

| Egypt | 3340 | 3111 | 5768 | 3584 | |

| Vietnam | 1990 | 4783 | 7995 | 6022 | |

| India | 1590 | 3168 | 14,158 | 4677 | |

| Myanmar | 1160 | No data | 6602 | 4645 |

| Country * | Cantril Ladder | Cantril Ladder (Gallup Worldwide Research Data) |

|---|---|---|

| Australia | 6.80 | 7.27 |

| Sweden | 6.88 | 7.31 |

| Canada | 6.86 | 7.33 |

| United States | 6.95 | 6.89 |

| Netherlands | 7.02 | 7.44 |

| Germany | 6.65 | 6.97 |

| United Kingdom | 6.56 | 6.84 |

| France | 6.63 | 6.49 |

| Japan | 5.93 | 5.92 |

| Italy | 6.26 | 6.00 |

| Spain | 6.67 | 6.31 |

| Greece | 6.21 | 5.36 |

| Czech Republic | 6.55 | 6.71 |

| Poland | 6.37 | 6.12 |

| Chile | 7.01 | 6.48 |

| Venezuela | 6.94 | 4.81 |

| Russia | 5.97 | 5.81 |

| Malaysia | 6.48 | 6.32 |

| Brazil | 6.66 | 6.42 |

| Mexico | 7.67 | 6.49 |

| Romania | 7.00 | 5.95 |

| China | 6.76 | 5.25 |

| Colombia | 7.39 | 6.26 |

| Thailand | 6.63 | 6.07 |

| South Africa | 6.38 | 4.72 |

| Mongolia | 6.16 | 5.13 |

| Sri Lanka | 7.03 | 4.47 |

| Philippines | 7.21 | 5.52 |

| Egypt | 6.15 | 4.42 |

| Vietnam | 6.89 | 5.10 |

| India | 7.23 | 4.19 |

| Myanmar | 5.89 | 4.31 |

References

- Kahneman, D.; Deaton, A. High income improves evaluation of life but not emotional well-being. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 16489–16493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Killingsworth, M.A. Experienced well-being rises with income, even above $75,000 per year. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2016976118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Killingsworth, M.A.; Kahneman, D.; Mellers, B. Income and emotional well-being: A conflict resolved. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2208661120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OECD. Guidelines On Measuring Subjective Well-Being; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jebb, A.T.; Tay, L.; Diener, E.; Oishi, S. Happiness, income satiation and turning points around the world. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2018, 2, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Kahneman, D.; Tov, W.; Arora, R. Income’s Association with Judgments of Life Versus Feelings. In International Differences in Well-Being; Diener, E., Helliwell, J., Kahneman, D., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2010; pp. 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson, B.; Wolfers, J. Subjective well-being and income: Is there any evidence of satiation? Am. Econ. Rev. 2013, 103, 598–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deaton, A. Income, health, and well-being around the world: Evidence from the Gallup World Poll. J. Econ. Perspect. 2008, 22, 53–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-García, V.; Zorondo-Rodríguez, F.; Angelsen, A.; Babigumira, R.; Pyhälä, A.; Wunder, S. Subjective well-being and income: Empirical patterns in the rural developing world. J. Happiness Stud. 2016, 17, 773–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, A.; Seligman, M. Using wellbeing for public policy: Theory, measurement, and recommendations. Int. J. Wellbeing 2016, 6, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helliwell, J.F.; Layard, R.; Sachs, J.D.; De Neve, J.-E.; Aknin, L.B.; Wang, S. (Eds.) World Happiness Report 2022; Sustainable Development Solutions Network: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, F.M.; Withey, S.B. Social Indicators of Well-Being: America’s Perception of Life Quality; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Michalos, A.C. Satisfaction and happiness. Soc. Indic. Res. 1980, 8, 385–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veenhoven, R. Is happiness relative? Soc. Indic. Res. 1991, 24, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantril, H. The Pattern of Human Concerns; Rutgers University Press: New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E. Subjective well-being. Psychol. Bull. 1984, 75, 542–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalos, A.C. Multiple discrepancies theory (MDT). Soc. Indic. Res. 1985, 36, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Emmons, R.A.; Larsen, R.J.; Griffin, S. The satisfaction with life scale. J. Pers. Assess. 1985, 49, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozma, A.; Stones, M.J. Longitudinal findings on a componential model of happiness. In Developments in Quality-of-Life Studies in Marketing; Sirgy, M.J., Meadow, H.L., Rahtz, D., Samli, A.C., Eds.; Academy of Marketing Science: Mississippi, MS, USA, 1992; Volume 4, pp. 139–142. [Google Scholar]

- Parducci, A. Happiness, Pleasure, and Judgment: The Contextual Theory and Its Applications; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman, D. Objective happiness. In Well-Being: The Foundations of Hedonic Psychology; Kahneman, D., Diener, E., Schwartz, N., Eds.; Russell Sage: New York, NY, USA, 1999; pp. 3–25. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, C.; Park, N.; Seligman, M.E.P. Orientations to happiness and life satisfaction: The full life versus the empty life. J. Happiness Stud. 2005, 6, 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, M.E.P. Authentic Happiness: Using the New Positive Psychology to Realize Your Potential for Lasting Fulfillment; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Vittersø, J.; Soholt, Y.; Hetland, A.; Thoresen, I.A.; Røysamb, E. Was Hercules happy? Some answers from a functional model of human well-being. Soc. Indic. Res. 2010, 95, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanjuan, P. Affect balance as a mediating variable between effective psychological functioning and satisfaction with life. J. Happiness Stud. 2011, 12, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powdthavee, N.; Van den Berg, B. Putting different price tags on the same health condition: Re-evaluating the well-being valuation approach. J. Health Econ. 2011, 30, 1032–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthrie, E.; Black, D.; Bagalkote, H.; Shaw, C.; Campbell, M.; Creed, F. Psychological stress and burnout in medical students: A five–year prospective longitudinal study. J. R. Soc. Med. 1998, 91, 237–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsch, H.; Kühling, J. Determinants of pro-environmental consumption: The role of reference groups and routine behavior. Ecol. Econ. 2009, 69, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastie, T.J.; Tibshirani, R.J. Generalized Additive Models; Chapman and Hall: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Blanchflower, D.G.; Oswald, A.J. Is well-being U-shaped over the life cycle? Soc. Sci. Med. 2008, 66, 1733–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frijters, P.; Beatton, T. The mystery of the U-shaped relationship between happiness and age. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2012, 82, 525–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Tay, L.; Oishi, S. Rising income and the subjective well-being of nations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2013, 104, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helliwell, J.F.; Huang, H.; Wang, S. The social foundations of world happiness. In World Happiness Report 2017; Helliwell, J.F., Layard, R., Sachs, J., Eds.; Sustainable Development Solutions Network: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 8–47. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, S.N. Stable and efficient multiple smoothing parameter estimation for generalized additive models. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2004, 99, 673–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, S.N. Fast stable direct fitting and smoothness selection for generalized additive models. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Stat. Methodol. 2008, 70, 495–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, S.N. Generalized Additive Models: An Introduction with R, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E.; Inglehart, R.; Tay, L. Theory and validity of life satisfaction scales. Soc. Indic. Res. 2013, 112, 497–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, F.; Lucas, R.E. Assessing the validity of single-item life satisfaction measures: Results from three large samples. Qual. Life Res. 2014, 23, 2809–2818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavot, W.; Diener, E. Review of the Satisfaction With Life Scale. Psychol. Assess. 1993, 5, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schimmack, U. Affect measurement in experience sampling research. J. Happiness Stud. 2003, 4, 79–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, D.; Tellegen, A. Issues in the dimensional structure of affect—Effects of descriptors, measurement scales, and rotation of factors. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 76, 820–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, D.; Gater, R.; Sartorius, N.; Ustun, T.B.; Piccinelli, M.; Gureje, O.; Rutter, C. The validity of two versions of the GHQ in the WHO study of mental illness in general health care. Psychol. Med. 1997, 27, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, C. The General Health Questionnaire. Occup. Med. 2007, 57, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Tella, R.; MacCulloch, R. Gross national happiness as an answer to the Easterlin Paradox? J. Dev. Econ. 2008, 86, 22–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsurumi, T.; Managi, S. Monetary valuations of life conditions in a consistent framework: The life satisfaction approach. J. Happiness Stud. 2017, 18, 1275–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, R.D. Democracies in Flux: The Evolution of Social Capital in Contemporary Society; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Frey, B.S.; Stutzer, A. What can economists learn from happiness research? J. Econ. Lit. 2002, 40, 402–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouwels, B.; Siegers, J.; Vlasblom, J.D. Income, working hours, and happiness. Econ. Lett. 2008, 99, 72–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, T.; Bardo, A.R.; Liu, D. Are East Asians happy to work more or less? Associations between working hours, relative income and happiness in China, Japan, South Korea and Taiwan. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 2016, 19, 264–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsch, H. Preferences over prosperity and pollution: Environmental valuation based on happiness surveys. Kyklos 2002, 55, 473–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsch, H. Environment and happiness: Valuation of air pollution using life satisfaction data. Ecol. Econ. 2006, 58, 801–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsch, H. Environmental welfare analysis: A life satisfaction approach. Ecol. Econ. 2007, 62, 544–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehdanz, K.; Maddison, D. Local environmental quality and life satisfaction in Germany. Ecol. Econ. 2008, 64, 787–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luechinger, S. Life satisfaction and transboundary air pollution. Econ. Lett. 2010, 107, 4–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackerron, G.; Mourato, S. Life satisfaction and air quality in London. Ecol. Econ. 2009, 68, 1441–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, S.; Moro, M. On the use of subjective well-being data for environmental valuation. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2010, 46, 249–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menz, T. Do people habituate to air pollution? Evidence from international life satisfaction data. Ecol. Econ. 2011, 71, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, S.; Akay, A.; Brereton, F.; Cunado, J.; Martinsson, P.; Moro, M.; Ningal, T.F. Life satisfaction and air quality in Europe. Ecol. Econ. 2013, 88, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrey, C.L.; Fleming, C.M.; Chan, A.Y. Estimating the cost of air pollution in South East Queensland: An application of the life satisfaction non-market valuation approach. Ecol. Econ. 2014, 97, 172–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrey, C.L.; Fleming, C.M. Valuing scenic amenity using life satisfaction data. Ecol. Econ. 2011, 72, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrey, C.L.; Fleming, C.M. Public greenspace and life satisfaction in urban Australia. Urban Stud. 2014, 51, 1290–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackerron, G.; Mourato, S. Happiness is greater in natural environments. Glob. Environ. Change 2013, 23, 992–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsurumi, T.; Managi, S. Environmental value of green spaces in Japan: An application of the life satisfaction approach. Ecol. Econ. 2015, 120, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsurumi, T.; Imauji, A.; Managi, S. Greenery and well-being: Assessing the monetary value of greenery by type. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 148, 152–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, M.A. The effect of crime on life satisfaction. J. Leg. Stud. 2008, 37, S325–S353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrey, C.L.; Fleming, C.M.; Manning, M. Perception or reality: What matters most when it comes to crime in your neighbourhood? Soc. Indic. Res. 2013, 119, 877–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, D. Quality of Life: Concept, Policy and Practice; Routledge: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Haybron, D.M. Two philosophical problems in the study of happiness. J. Happiness Stud. 2000, 1, 207–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockström, J.; Steffen, W.; Noone, K.; Persson, Å.; Chapin, F.S.; Lambin, E.F.; Lenton, T.M.; Scheffer, M.; Folke, C.; Schellnhuber, H.J.; et al. A safe operating space for humanity. Nature 2009, 461, 472–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffen, W.; Richardson, K.; Rockström, J.; Cornell, S.E.; Fetzer, I.; Bennett, E.M.; Biggs, R.; Carpenter, S.R.; De Vries, W.; De Wit, C.A.; et al. Planetary boundaries: Guiding human development on a changing planet. Science 2015, 347, 1259855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiedmann, T.; Lenzen, M.; Keyßer, L.T.; Steinberger, J.K. Scientists’ warning on affluence. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, D.W.; Fanning, A.L.; Lamb, W.F.; Steinberger, J.K. A good life for all within planetary boundaries. Nat. Sustain. 2018, 1, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raworth, K. Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist; Random House Business: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Easterlin, R.A. Does economic growth improve the human lot? Some empirical evidence. In Nations and Households in Economic Growth; David, P.A., Reder, M.W., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1974; pp. 89–125. [Google Scholar]

- Easterlin, R.A.; McVey, L.A.; Switek, M.; Sawangfa, O.; Zweig, J.S. The happiness–income paradox revisited. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 22463–22468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, A.E.; Flèche, S.; Layard, R.; Powdthavee, N.; Ward, G. The Origins of Happiness: The Science of Well-Being Over the Life Course; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Tsurumi, T.; Yamaguchi, R.; Kagohashi, K.; Managi, S. Material and relational consumption to improve subjective well-being: Evidence from rural and urban Vietnam. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 310, 127499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tov, W.; Diener, E. Culture and subjective well-being. In Handbook of Cultural Psychology; Kitayama, S., Cohen, D., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 691–713. [Google Scholar]

- Mesquita, B. Emotions as dynamic cultural phenomena. In Handbook of Affective Sciences; Davidson, R.J., Scherer, K.R., Goldsmith, H.H., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2003; pp. 871–890. [Google Scholar]

| Variables | Survey Question | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Life satisfaction | Overall, how satisfied are you with your life? Responses are given on an integer scale from 1 (not at all satisfied) to 5 (completely satisfied). | 5: Completely satisfied, 1: Not at all satisfied; five-point scale (standardized into 0 to 1). |

| Cantril ladder | Imagine a ladder with steps numbered from 0 to 10 at the top. The top of the ladder represents the best possible life for you and the bottom of the ladder represents the worst possible life for you. On which step of the ladder would you say you personally feel that you stand at this time? | 11-point scale, 10: Best possible life, 0: Worst possible life (standardized into 0 to 1) |

| Subjective happiness | Overall, how happy are you with your life? Responses are given on an integer scale from 1 (unhappy) to 5 (very happy). | 5: Very happy, 1: unhappy, 5-point scale (standardized into 0 to 1). |

| Affect balance | How often have you felt or experienced the following feelings or actions? Please answer for number of times per week. Pleasure, Anger, Sadness, Enjoyment, Smile | 3: Often, 2: Sometimes, 1: Rarely, 0: Not at all Affect balance = Average score of positive affect (Pleasure, Enjoyment, Smile)—Average score of negative affect (Anger, Sadness). Standardized into 0 to 1. |

| Mental health (12-item general health questionnaire (GHQ–12)) | The response to each of the GHQ’s 12 questions is assigned a score based on a four-point Likert scale (from 0 to 3). The total score (between 0 and 36) is used as a measure of an individual’s mental health. The larger the score, the better the respondent’s mental health. | 37 possible total scores ranging from 0 to 36 (standardized into 0 to 1). |

| Eudaimonia | Overall, to what extent do you feel that the things you do in your life are worthwhile? Responses are given on an integer scale from 0 (not at all worthwhile) to 10 (completely worthwhile). | 11-point scale from 0 to 10 (standardized into 0 to 1). |

| Annual household income (USD) | Annual household income before tax (USD) Note: Nominal value | Each country’s currency unit is converted into USD using the annual exchange rate for 2015. |

| Age | Respondent’s age | |

| Female dummy | Female dummy is coded 1 if the respondent is female, otherwise 0. | |

| Marital dummy | Marital dummy is coded as 1 if the respondent answered married and does not distinguish whether the person was previously married. |

| Country * | Sample Size | Life Satisfaction | Cantril Ladder | Subjective Happiness | Affect Balance | Mental Health | Eudaimonia | Annual Household Income (USD) (Average) | Annual Household Income (USD) (Median) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | 1727 | 0.707 (0.273) | 0.680 (0.198) | 0.732 (0.286) | 0.617 (0.192) | 0.638 (0.186) | 0.721 (0.216) | 56,011 (37,440) | 0.707 (0.273) |

| Sweden | 1115 | 0.740 (0.252) | 0.688 (0.197) | 0.741 (0.248) | 0.611 (0.191) | 0.648 (0.154) | 0.699 (0.210) | 51,956 (34,716) | 0.740 (0.252) |

| Canada | 1215 | 0.742 (0.256) | 0.686 (0.194) | 0.762 (0.262) | 0.632 (0.186) | 0.654 (0.165) | 0.728 (0.211) | 48,783 (34,278) | 0.742 (0.256) |

| United States | 10,173 | 0.747 (0.265) | 0.695 (0.208) | 0.768 (0.268) | 0.622 (0.190) | 0.646 (0.189) | 0.751 (0.215) | 60,126 (46,223) | 0.747 (0.265) |

| Netherlands | 1107 | 0.748 (0.237) | 0.702 (0.164) | 0.735 (0.242) | 0.648 (0.184) | 0.673 (0.169) | 0.718 (0.173) | 44,496 (32,122) | 0.748 (0.237) |

| Germany | 2754 | 0.703 (0.269) | 0.665 (0.192) | 0.708 (0.260) | 0.645 (0.196) | 0.641 (0.172) | 0.708 (0.202) | 45,488 (36,180) | 0.703 (0.269) |

| United Kingdom | 2667 | 0.698 (0.262) | 0.656 (0.208) | 0.712 (0.279) | 0.615 (0.183) | 0.624 (0.184) | 0.699 (0.225) | 57,251 (40,996) | 0.698 (0.262) |

| France | 1935 | 0.717 (0.266) | 0.663 (0.181) | 0.750 (0.248) | 0.608 (0.197) | 0.636 (0.153) | 0.682 (0.190) | 40,843 (32,963) | 0.717 (0.266) |

| Japan | 9784 | 0.589 (0.261) | 0.593 (0.197) | 0.657 (0.233) | 0.604 (0.187) | 0.638 (0.184) | 0.627 (0.237) | 50,899 (32,657) | 0.589 (0.261) |

| Italy | 1852 | 0.640 (0.241) | 0.626 (0.181) | 0.653 (0.233) | 0.547 (0.201) | 0.635 (0.135) | 0.694 (0.183) | 40,396 (30,730) | 0.640 (0.241) |

| Spain | 1934 | 0.732 (0.244) | 0.667 (0.177) | 0.737 (0.254) | 0.600 (0.183) | 0.663 (0.160) | 0.753 (0.194) | 37,365 (29,469) | 0.732 (0.244) |

| Greece | 1228 | 0.656 (0.259) | 0.621 (0.188) | 0.685 (0.237) | 0.544 (0.197) | 0.590 (0.178) | 0.679 (0.184) | 19,468 (15,567) | 0.656 (0.259) |

| Czech Republic | 1213 | 0.658 (0.208) | 0.655 (0.182) | 0.684 (0.189) | 0.597 (0.161) | 0.642 (0.154) | 0.688 (0.178) | 15,166 (13,023) | 0.658 (0.208) |

| Poland | 1816 | 0.685 (0.231) | 0.637 (0.189) | 0.699 (0.216) | 0.607 (0.188) | 0.631 (0.172) | 0.711 (0.203) | 16,821 (21,080) | 0.685 (0.231) |

| Chile | 1073 | 0.749 (0.233) | 0.701 (0.171) | 0.773 (0.215) | 0.656 (0.177) | 0.680 (0.171) | 0.863 (0.171) | 16,013 (14,205) | 0.749 (0.233) |

| Venezuela | 742 | 0.763 (0.254) | 0.694 (0.208) | 0.789 (0.219) | 0.645 (0.193) | 0.694 (0.168) | 0.914 (0.165) | 34,088 (34,087) | 0.763 (0.254) |

| Russia | 2133 | 0.604 (0.244) | 0.597 (0.186) | 0.685 (0.202) | 0.586 (0.189) | 0.640 (0.157) | 0.666 (0.223) | 11,531 (8693) | 0.604 (0.244) |

| Malaysia | 1032 | 0.649 (0.254) | 0.648 (0.182) | 0.710 (0.241) | 0.620 (0.171) | 0.649 (0.,176) | 0.690 (0.191) | 18,708 (13,424) | 0.649 (0.254) |

| Brazil | 2117 | 0.635 (0.257) | 0.666 (0.192) | 0.678 (0.235) | 0.624 (0.175) | 0.687 (0.186) | 0.896 (0.176) | 15,103 (14,267) | 0.635 (0.257) |

| Mexico | 1527 | 0.795 (0.208) | 0.767 (0.155) | 0.827 (0.189) | 0.676 (0.170) | 0.709 (0.156) | 0.925 (0.136) | 12,281 (11,730) | 0.795 (0.208) |

| Romania | 1217 | 0.708 (0.231) | 0.700 (0.162) | 0.730 (0.220) | 0.608 (0.189) | 0.653 (0.159) | 0.759 (0.176) | 15,799 (30,572) | 0.708 (0.231) |

| China | 19,877 | 0.719 (0.199) | 0.676 (0.170) | 0.711 (0.198) | 0.692 (0.172) | 0.726 (0.155) | 0.725 (0.174) | 20,357 (12,970) | 0.719 (0.199) |

| Colombia | 1035 | 0.812 (0.204) | 0.739 (0.159) | 0.825 (0.190) | 0.664 (0.169) | 0.724 (0.159) | 0.933 (0.133) | 10,833 (11,220) | 0.812 (0.204) |

| Thailand | 1096 | 0.697 (0.228) | 0.663 (0.181) | 0.700 (0.200) | 0.651 (0.167) | 0.691 (0.165) | 0.805 (0.176) | 17,744 (17,744) | 0.697 (0.228) |

| South Africa | 987 | 0.699 (0.259) | 0.638 (0.193) | 0.756 (0.268) | 0.603 (0.186) | 0.615 (0.198) | 0.716 (0.199) | 21,803 (20,913) | 0.699 (0.259) |

| Mongolia | 456 | 0.805 (0.243) | 0.616 (0.189) | 0.874 (0.193) | 0.657 (0.183) | 0.719 (0.130) | 0.661 (0.220) | 5403 (3271) | 0.805 (0.243) |

| Sri Lanka | 451 | 0.803 (0.184) | 0.703 (0.181) | 0.835 (0.165) | 0.673 (0.186) | 0.795 (0.129) | 0.738 (0.182) | 4121 (2046) | 0.803 (0.184) |

| Philippines | 1515 | 0.736 (0.228) | 0.721 (0.159) | 0.793 (0.211) | 0.614 (0.155) | 0.706 (0.162) | 0.771 (0.162) | 11,318 (15,058) | 0.736 (0.228) |

| Egypt | 569 | 0.730 (0.272) | 0.615 (0.223) | 0.711 (0.271) | 0.596 (0.209) | 0.715 (0.220) | 0.671 (0.268) | 5768 (5918) | 0.730 (0.272) |

| Vietnam | 1678 | 0.613 (0.255) | 0.689 (0.162) | 0.710 (0.238) | 0.625 (0.163) | 0.704 (0.158) | 0.762 (0.163) | 7995 (5900) | 0.613 (0.255) |

| India | 4833 | 0.782 (0.225) | 0.723 (0.179) | 0.795 (0.233) | 0.610 (0.168) | 0.689 (0.174) | 0.746 (0.192) | 14,158 (18,232) | 0.782 (0.225) |

| Myanmar | 1057 | 0.612 (0.172) | 0.589 (0.150) | 0.620 (0.169) | 0.740 (0.126) | 0.780 (0.094) | 0.606 (0.155) | 6602 (11,830) | 0.612 (0.172) |

| Country * | Sample Size | Age | Female Dummy | Marital Dummy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | 1727 | 46.327 (16.560) | 0.510 (0.500) | 0.527 (0.499) |

| Sweden | 1115 | 47.994 (16.883) | 0.522 (0.500) | 0.367 (0.482) |

| Canada | 1215 | 46.855 (16.367) | 0.498 (0.500) | 0.448 (0.497) |

| United States | 10,173 | 46.178 (16.560) | 0.510 (0.500) | 0.527 (0.499) |

| Netherlands | 1107 | 48.156 (16.546) | 0.516 (0.500) | 0.437 (0.496) |

| Germany | 2754 | 48.613 (15.670) | 0.500 (0.500) | 0.423 (0.494) |

| United Kingdom | 2667 | 47.009 (16.064) | 0.499 (0.500) | 0.462 (0.499) |

| France | 1935 | 47.917 (15.754) | 0.484 (0.500) | 0.503 (0.500) |

| Japan | 9784 | 49.776 (13.928) | 0.555 (0.497) | 0.691 (0.462) |

| Italy | 1852 | 48.924 (15.001) | 0.500 (0.500) | 0.542 (0.498) |

| Spain | 1934 | 46.782 (14.233) | 0.493 (0.500) | 0.530 (0.499) |

| Greece | 1228 | 43.741 (11.652) | 0.493 (0.500) | 0.530 (0.499) |

| Czech Republic | 1213 | 47.008 (16.006) | 0.492 (0.500) | 0.405 (0.491) |

| Poland | 1816 | 46.094 (15.713) | 0.490 (0.500) | 0.519 (0.500) |

| Chile | 1073 | 36.458 (12.917) | 0.530 (0.499) | 0.342 (0.475) |

| Venezuela | 742 | 39.175 (12.437) | 0.503 (0.500) | 0.371 (0.484) |

| Russia | 2133 | 42.017 (13.349) | 0.460 (0.499) | 0.246 (0.491) |

| Malaysia | 1032 | 33.409 (10.214) | 0.535 (0.499) | 0.464 (0.499) |

| Brazil | 2117 | 37.645 (12.962) | 0.483 (0.500) | 0.511 (0.500) |

| Mexico | 1527 | 38.137 (13.822) | 0.500 (0.500) | 0.485 (0.500) |

| Romania | 1217 | 47.134 (15.193) | 0.493 (0.500) | 0.579 (0.494) |

| China | 19,877 | 41.150 (12.381) | 0.506 (0.500) | 0.754 (0.431) |

| Colombia | 1035 | 37.927 (13.190) | 0.485 (0.500) | 0.384 (0.487) |

| Thailand | 1096 | 38.103 (11.570) | 0.519 (0.500) | 0.501 (0.500) |

| South Africa | 987 | 38.989 (13.467) | 0.479 (0.500) | 0.457 (0. 498) |

| Mongolia | 456 | 39.434 (14.599) | 0.465 (0.499) | 0.689 (0.464) |

| Sri Lanka | 451 | 42.293 (15.555) | 0.475 (0.500) | 0.816 (0.388) |

| Philippines | 1515 | 37.232 (12.688) | 0.486 (0.500) | 0.442 (0.500) |

| Egypt | 569 | 39.074 (12.884) | 0.555 (0.497) | 0.550 (0.498) |

| Vietnam | 1678 | 31.817 (10.326) | 0.521 (0.500) | 0.569 (0.495) |

| India | 4833 | 34.740 (11.761) | 0.589 (0.492) | 0.665 (0.472) |

| Myanmar | 1057 | 38.710 (14.196) | 0.460 (0.499) | 0.580 (0.494) |

| Model A | Model B | Model C | Model D | Model E | Model F | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Life satisfaction | Cantril ladder | Subjective happiness | Eudaimonia | Affect balance | Mental health | |

| Female dummy | 1.27 × 10−2 *** (7.66) | 2.33 × 10−2 *** (18.30) | 1.79 × 10−2 *** (11.15) | 1.70 × 10−2 *** (12.30) | 3.31 × 10−2 * (2.57) | −8.78 × 10−2 *** (−7.39) |

| Age | −9.70 × 10−3 *** (−27.41) | −5.71 × 10−3 *** (−21.07) | −9.26 × 10−3 *** (−27.13) | −5.58 × 10−3 *** (−19.00) | −4.15 × 10−3 *** (−15.12) | −3.50 × 10−3 *** (−13.83) |

| Age squared | 1.09 × 10−4 *** (28.25) | 6.82 × 10−5 *** (22.99) | 1.01 × 10−4 *** (27.00) | 6.89 × 10−5 *** (21.46) | 5.74 × 10−5 *** (19.10) | 5.30 × 10−5 *** (19.15) |

| Marital dummy | 6.54 × 10−2 *** (33.29) | 4.89 × 10−2 *** (32.44) | 7.57 × 10−2 *** (39.87) | 4.45 × 10−2 *** (27.25) | 2.73 × 10−2 *** (17.85) | 2.31 × 10−2 *** (16.38) |

| Constant term | 6.72 × 10−1 *** (87.60) | 6.06 × 10−1 *** (103.13) | 7.42 × 10−1 *** (100.21) | 6.39 × 10−1 *** (100.47) | 6.13 × 10−1 *** (102.99) | 6.31 × 10−1 *** (114.87) |

| Approximate significance of smooth terms (F values) | 330.2 *** | 470.1 *** | 243.0 *** | 269.9 *** | 139.1 *** | 160.7 *** |

| Generalized cross validation (GCV) | 34.43 | 34.35 | 35.75 | 34.75 | 33.32 | 32.15 |

| Adjusted R squared | 0.135 | 0.133 | 0.104 | 0.166 | 0.092 | 0.119 |

| Time-fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Country-fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 83,915 | 83,915 | 83,915 | 83,915 | 83,915 | 83,915 |

| Variables | Survey Question | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Subjective health | All in all, how would you describe your state of health? | 5: Very good, 4: Good, 3: Neither, 2: Poor, 1: Very poor, five-point scale. |

| Social capital | Please select all items that you feel important in your life. From items that you have chosen to be important in your life, please select all items that you are satisfied with. A: Relationship with family B: Relationship with friends and acquaintances | 1: the respondent chooses both A and B. 0.5: the respondent chooses either A or B. 0: the respondent chooses neither A nor B. |

| Working hours | Please tell us about your average working day. Please select average hours that you spend on working (including housework) or school hours. | Unit: hour 0: 0 h 0.15: Less than 15 min 0.3: 15 min to less than 30 min 0.75: 30 min to less than 1 h 1.5: 1 h to less than 2 h 2.5: 2 h to less than 3 h 3.5: 3 h to less than 4 h 4.5: 4 h to less than 5 h 5.5: 5 h to less than 6 h 6.5: 6 h to less than 7 h 7.5: 7 h to less than 8 h 8.5: 8 h to less than 9 h 9.5: 9 h to less than 10 h 10.5: 10 h to less than 11 h 11.5: 11 h to less than 12 h 12.5: 12 h or more |

| Environment | Now we will ask about your living environment. Please select all items that you are dissatisfied with. A: Landscape/Scenery B: Air pollution C: Quality of domestic water D: Surrounding green | 1: all items selected 0.75: three items selected 0.5: two items selected 0.25: one items selected 0: no item selected |

| Safety | Please tell us about the safety of your neighborhood. | 4: Very safe, 3: Moderately safe, 2: Slightly dangerous, 1: Very dangerous, four-point scale. |

| Model G | Model H | Model I | Model J | Model K | Model L | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Life satisfaction | Cantril ladder | Subjective happiness | Eudaimonia | Affect balance | Mental health | |

| Female dummy | 9.14 × 10−3 *** (6.01) | 1.99 × 10−2 *** (17.03) | 1.51 × 10−2 *** (10.38) | 1.57 × 10−2 *** (12.23) | 3.69 × 10−3 *** (3.09) | −1.05 × 10−3 *** (−9.85) |

| Age | −5.82 × 10−3 *** (−17.88) | −2.67 × 10−3 *** (−10.66) | −5.49 × 10−3 *** (−17.67) | −2.89 × 10−3 *** (−10.53) | −1.95 × 10−3 *** (−7.63) | −7.09 × 10−4 ** (−3.10) |

| Age squared | 7.24 × 10−5 *** (20.16) | 3.87 × 10−5 *** (14.02) | 6.51 × 10−5 *** (18.98) | 4.42 × 10−5 *** (14.59) | 3.78 × 10−5 *** (13.41) | 2.67 × 10−5 *** (10.60) |

| Marital dummy | 4.44 × 10−2 *** (24.84) | 3.30 × 10−2 *** (23.98) | 5.40 × 10−2 *** (31.60) | 2.80 × 10−2 *** (18.59) | 1.16 × 10−2 *** (8.25) | 6.86 × 10−2 *** (5.47) |

| Subjective health | 9.21 × 10−2 *** (99.09) | 6.90 × 10−2 *** (96.56) | 8.88 × 10−2 *** (99.96) | 6.77 × 10−2 *** (86.37) | 5.66 × 10−2 *** (77.54) | 3.27 × 10−2 *** (42.68) |

| Social capital | 8.37 × 10−2 *** (34.60) | 6.32 × 10−2 *** (33.98) | 1.05 × 10−1 *** (45.51) | 8.41 × 10−2 *** (41.22) | 1.11 × 10−2 *** (58.15) | 7.15 × 10−2 *** (42.09) |

| Working hours | −1.68 × 10−3 *** (−6.93) | −1.76 × 10−3 *** (−9.43) | −8.60 × 10−4 *** (−3.71) | 1.10 × 10−3 (0.536) | 1.74 × 10−3 *** (9.10) | −4.09 × 10−3 * (−2.40) |

| Environment | −6.04 × 10−2 *** (−22.42) | −5.66 × 10−2 *** (−27.30) | −4.50 × 10−2 *** (−17.47) | −2.47 × 10−2 *** (−10.87) | −7.89 × 10−3 *** (−3.73) | −4.05 × 10−2 *** (−21.39) |

| safety | 3.46 × 10−2 *** (31.76) | 2.45 × 10−2 *** (29.22) | 3.76 × 10−2 *** (36.07) | 2.81 × 10−2 *** (30.53) | 2.73 × 10−2 *** (31.87) | 3.27 × 10−2 *** (42.68) |

| Constant term | 1.66 × 10−1 *** (20.563) | 2.32 × 10−1 *** (37.27) | 2.28 × 10−1 *** (29.51) | 2.46 × 10−1 *** (36.09) | 2.49 × 10−1 *** (39.23) | 2.34 × 10−1 *** (41.10) |

| Approximate significance of smooth terms (F values) | 191.1 *** | 312.7 *** | 115.3 *** | 136.1 *** | 44.1 *** | 54.32 *** |

| Generalized cross validation (GCV) | 34.25 | 34.56 | 35.85 | 34.46 | 33.75 | 32.64 |

| Adjusted R squared | 0.295 | 0.288 | 0.285 | 0.299 | 0.242 | 0.309 |

| Time-fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Country-fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 83,915 | 83,915 | 83,915 | 83,915 | 83,915 | 83,915 |

| Country * | GNI per Capita, Calculated Using the World Bank Atlas Method (Current USD) in 2015 | Gallup Self-Reported Median Household Income [USD] in 2013 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-Income Economies (GNI per capita ≥ USD 12,476) | Australia | 60,050 | 46,555 |

| Sweden | 57,900 | 50,514 | |

| Canada | 57,250 | 41,280 | |

| United States | 55,980 | 43,585 | |

| Netherlands | 48,850 | 38,584 | |

| Germany | 45,790 | 33,333 | |

| United Kingdom | 43,700 | 31,617 | |

| France | 40,710 | 31,112 | |

| Japan | 38,840 | 33,822 | |

| Italy | 32,830 | 20,085 | |

| Spain | 28,380 | 21,959 | |

| Greece | 20,270 | 17,777 | |

| Czech Republic | 18,150 | 22,913 | |

| Poland | 13,310 | 15,338 | |

| Upper Middle-Income Economies (GNI per capita = USD 4036–USD 12,475) | Chile | 14,100 ** | 8098 |

| Venezuela | 11,780 *** | 11,239 | |

| Russia | 11,450 | 11,724 | |

| Malaysia | 10,570 | 11,207 | |

| Brazil | 9990 | 7522 | |

| Mexico | 9710 | 11,680 | |

| Romania | 9510 | 7322 | |

| China | 7900 | 6180 | |

| Colombia | 7140 | 6544 | |

| Thailand | 5720 | 7029 | |

| Lower Middle-Income Economies (GNI per capita = USD 1026–USD 4035) | South Africa | 6080 **** | 5217 |

| Mongolia | 3870 | 5922 | |

| Sri Lanka | 3800 | 3242 | |

| Philippines | 3550 | 2401 | |

| Egypt | 3340 | 3111 | |

| Vietnam | 1990 | 4783 | |

| India | 1590 | 3168 | |

| Myanmar | 1160 | No data |

| Model A | Model B | Model C | Model D | Model E | Model F | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Life satisfaction | Cantril ladder | Subjective happiness | Eudaimonia | Affect balance | Mental health | |

| Female dummy | 1.33 × 10−2 *** (8.55) | 2.27 × 10−2 *** (14.35) | 1.98 × 10−2 *** (13.33) | 1.54 × 10−2 *** (13.46) | 3.63 × 10−2 * (2.34) | −8.85 × 10−2 *** (−7.35) |

| Age | −5.54 × 10−3 *** (−24.65) | −5.65 × 10−3 *** (−23.39) | −9.43 × 10−3 *** (−23.98) | −5.44 × 10−3 *** (−16.89) | −4.24 × 10−3 *** (−14.46) | −3.53 × 10−3 *** (−13.56) |

| Age squared | 1.22 × 10−4 *** (24.43) | 5.43 × 10−5 *** (24.34) | 1.04 × 10−4 *** (24.47) | 6.33 × 10−5 *** (24.34) | 5.54 × 10−5 *** (16.47) | 5.25 × 10−5 *** (13.23) |

| Marital dummy | 5.54 × 10−2 *** (32.97) | 4.67 × 10−2 *** (28.23) | 6.54 × 10−2 *** (37.44) | 4.23 × 10−2 *** (25.27) | 2.86 × 10−2 *** (19.45) | 2.24 × 10−2 *** (18.34) |

| Constant term | 5.64 × 10−1 *** (95.75) | 5.26 × 10−1 *** (105.77) | 7.74 × 10−1 *** (113.42) | 6.65 × 10−1 *** (109.38) | 6.06 × 10−1 *** (105.54) | 6.42 × 10−1 *** (124.73) |

| Approximate significance of smooth terms (F values) | 240.7 *** | 264.7 *** | 228.0 *** | 237.7 *** | 126.7 *** | 157.9 *** |

| Generalized cross validation (GCV) | 23.74 | 26.64 | 25.28 | 27.32 | 27.35 | 26.74 |

| Adjusted R squared | 0.124 | 0.123 | 0.105 | 0.154 | 0.096 | 0.106 |

| Time-fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Country-fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 40,520 | 40,520 | 40,520 | 40,520 | 40,520 | 40,520 |

| Model A | Model B | Model C | Model D | Model E | Model F | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Life satisfaction | Cantril ladder | Subjective happiness | Eudaimonia | Affect balance | Mental health | |

| Female dummy | 1.25 × 10−2 *** (9.23) | 2.43 × 10−2 *** (15.13) | 1.86 × 10−2 *** (11.21) | 1.42 × 10−2 *** (11.85) | 2.53 × 10−2 *** (2.65) | −7.53 × 10−2 *** (−3.24) |

| Age | −4.78 × 10−3 *** (−23.43) | −4.59 × 10−3 *** (−20.04) | −7.21 × 10−3 *** (−21.54) | −5.25 × 10−3 *** (−13.64) | −4.31 × 10−3 *** (−12.63) | −4.53 × 10−3 *** (−11.12) |

| Age squared | 1.32 × 10−4 *** (23.96) | 5.21 × 10−5 *** (16.53) | 1.22 × 10−4 *** (26.25) | 5.52 × 10−5 *** (20.76) | 5.75 × 10−5 *** (13.66) | 5.35 × 10−5 *** (14.76) |

| Marital dummy | 5.11 × 10−2 *** (23.53) | 4.26 × 10−2 *** (22.79) | 6.33 × 10−2 *** (23.43) | 4.55 × 10−2 *** (15.34) | 2.31 × 10−2 *** (16.80) | 2.12 × 10−2 *** (15.74) |

| Constant term | 5.42 × 10−1 *** (87.85) | 3.36 × 10−1 *** (103.46) | 4.44 × 10−1 *** (132.367) | 6.53 × 10−1 *** (103.75) | 6.25 × 10−1 *** (113.78) | 6.42 × 10−1 *** (113.44) |

| Approximate significance of smooth terms (F values) | 223.7 *** | 253.3 *** | 225.1 *** | 242.5 *** | 141.4 *** | 134.9 *** |

| Generalized cross validation (GCV) | 21.53 | 23.34 | 22.14 | 26.69 | 25.57 | 23.35 |

| Adjusted R squared | 0.125 | 0.122 | 0.101 | 0.143 | 0.091 | 0.112 |

| Time-fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Country-fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 31,849 | 31,849 | 31,849 | 31,849 | 31,849 | 31,849 |

| Model A | Model B | Model C | Model D | Model E | Model F | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Life satisfaction | Cantril ladder | Subjective happiness | Eudaimonia | Affect balance | Mental health | |

| Female dummy | 1.51 × 10−2 *** (3.21) | 2.14 × 10−2 *** (6.26) | 1.86 × 10−2 *** (4.35) | 1.32 × 10−2 *** (7.41) | 3.21 × 10−2 * (2.34) | −5.64 × 10−2 *** (−3.64) |

| Age | −5.31 × 10−3 *** (−8.42) | −5.23 × 10−3 *** (−13.67) | −9.34 × 10−3 *** (−13.86) | −5.21 × 10−3 *** (−9.32) | −3.42 × 10−3 *** (−7.79) | −3.23 × 10−3 *** (−5.46) |

| Age squared | 1.41 × 10−4 *** (13.31) | 5.49 × 10−5 *** (15.32) | 1.24 × 10−4 *** (12.52) | 2.36 × 10−5 *** (13.78) | 4.76 × 10−5 *** (7.23) | 5.35 × 10−5 *** (4.35) |

| Marital dummy | 5.45 × 10−2 *** (23.97) | 4.32 × 10−2 *** (15.68) | 4.53 × 10−2 *** (24.68) | 4.35 × 10−2 *** (12.36) | 1.46 × 10−2 *** (11.97) | 2.36 × 10−2 *** (10.36) |

| Constant term | 2.35 × 10−1 *** (56.97) | 3.96 × 10−1 *** (64.34) | 2.97 × 10−1 *** (45.08) | 3.99 × 10−1 *** (56.36) | 4.26 × 10−1 *** (41.57) | 3.56 × 10−1 *** (47.35) |

| Approximate significance of smooth terms (F values) | 143.6 *** | 153.4 *** | 143.3 *** | 142.4 *** | 93.2 *** | 104.3 *** |

| Generalized cross validation (GCV) | 13.35 | 18.34 | 21.35 | 23.24 | 24.324 | 25.32 |

| Adjusted R squared | 0.113 | 0.114 | 0.093 | 0.134 | 0.086 | 0.078 |

| Time-fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Country-fixed effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 13,805 | 13,805 | 13,805 | 13,805 | 13,805 | 13,805 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tsurumi, T.; Managi, S. Income and Subjective Well-Being: The Importance of Index Choice for Sustainable Economic Development. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5266. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125266

Tsurumi T, Managi S. Income and Subjective Well-Being: The Importance of Index Choice for Sustainable Economic Development. Sustainability. 2025; 17(12):5266. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125266

Chicago/Turabian StyleTsurumi, Tetsuya, and Shunsuke Managi. 2025. "Income and Subjective Well-Being: The Importance of Index Choice for Sustainable Economic Development" Sustainability 17, no. 12: 5266. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125266

APA StyleTsurumi, T., & Managi, S. (2025). Income and Subjective Well-Being: The Importance of Index Choice for Sustainable Economic Development. Sustainability, 17(12), 5266. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17125266