3.1. Taverns in the Cultural Landscape of Poland

Taverns played an important role in the former landscape of Poland. They served as places of rest, meeting, entertainment, and provisioning for travelers, merchants, and rural populations. They combined gastronomic and hospitality functions. Larger and more well-known establishments had special bedrooms where the nobility, gathering for meetings, could spend the night comfortably. In the tavern, various groups of people met: peasants, nobility, and artists, representing different social classes. Taverns often served as centers for local communities, places where information was exchanged, celebrations were held, and various social activities took place [

4]. Musical performances and theatrical plays were held here, as well as weddings and other family events. Trade transactions were conducted, and goods were exchanged. Tavern owners were not only innkeepers but also craftsmen, shoemakers, blacksmiths, farmers, or people of other professions [

5,

6].

Due to their functions, taverns are divided into “inns” (with overnight accommodations) and “non-inns”. The former, which are the subject of this article, were significant as elements of the communication network. They were equipped with sleeping rooms and stables, and were therefore also called “guesthouses”. The latter, on the other hand, typically only offered drinks and the innkeeper’s living quarters [

7].

Taverns were usually spaced every 3–4 miles, and in less densely populated areas, every 6–8 miles (1 mile = approximately 7400 m). This corresponds to the distance typically covered by merchants traveling with goods in one day. The location of taverns was also related to the provision of draft horses for the army, which was important, for example, in the transport of food supplies for military units. The Constitution of 1789 stated that a party providing horses for the army could not send them farther than 3 miles, which meant that horses had to be exchanged after covering such a distance. Furthermore, the taverns’ equipment with stables and their frequent use as an alternative to postal infrastructure indicate their possible connection to the organization of the army’s supply system [

8]. Taverns, inns, and, postal stations—these buildings were essential elements of road infrastructure, where the speed of travel and the length of daily distances were determined by the capabilities of draft horses and the condition of the travelers [

9].

The oldest preserved Polish taverns, some of which are still operational today, date back to the 18th century. Among them is the Tavern in Jeleśnia, located along the main route of the Wooden Architecture Trail in the Silesian Voivodeship [

10]. Its well-preserved gable construction with a Polish-style broken roof is noteworthy. The tavern’s interior is decorated with paper cutouts, a tradition for which the Jeleśnia region is famous. The “Old Inn” in Jeleśnia was once one of many such facilities in the villages of the Beskids. The beginnings of the inn, which currently serves as a catering facility, as it did in the past. It is one of the monuments located on the Wooden Architecture Trail of the Silesian Voivodeship. The town of Jeleśnia lies on the border of the Żywiec Beskid and the Makowski Beskid, in the southeastern corner of the Silesian Voivodeship. The inn building most likely dates back to the 18th century, although there are many speculations that it is an earlier building, built by Wallachian settlers. In any case, the date 1774 is visible on the ceiling. The inn was located at a popular market place, located on the merchant route. Beskid bandits used to visit here—such as Proćpak, famous in the local area. The restaurant currently operating in the Jeleśnia Inn advertises itself, among other things, with dishes unknown elsewhere. Events with highland music are also organized here in a stylish, regional setting. Another example is the Austeria Miejska in Sławków [

11,

12]. Austeria (from Italian) is an old Polish term for an inn of the highest standard, well-equipped and with a wide range of all kinds of food and drinks, located in a solid, spacious building, which also serves as a restaurant and a hotel, and stable in the inn. The building is a classic example of a wooden old Polish inn. It was built on the plan of the letter “T”. The building most likely dates back to 1781, but this monument dates back to much earlier times, because over the centuries it was rebuilt many times, although it was always located in the same principal place at the Silesian highway, which was part of the main artery leading through the Market Square. This is also evidenced by, among others, the 13th-century walls discovered under the foundations of the Austeria and the very numerous fragments of innkeepers’ ceramics found during earthworks in various parts of the building. The Austeria has always been and is the property of the city, supervised and managed by the city authorities, and each time leased. An interesting object is also the “Rzym” Tavern in Sucha Beskidzka. It is a wooden, single-story building with a log construction on a stone foundation. It is said that Adam Mickiewicz mentioned this tavern in his poem “Pani Twardowska”, in which the sorcerer Twardowski meets the Devil himself at the “Rzym” tavern [

13]. These examples highlight the diversity of taverns and inns, which preserve cultural heritage while adapting to contemporary needs. Former inns often become tourist attractions, presenting local traditions, culture, and history.

3.2. Medieval Taverns

In the medieval period, travel was difficult due to political instability, threats from bandits, and the lack of transport infrastructure. Nevertheless, trade and pilgrimage routes existed, allowing for contact between cultures and the exchange of goods.

The first taverns in Poland emerged in the 10th century. They were referred to by the Latin term “taberna”. In these taverns, people ate meals, rested, and prepared horses for further travel. Wealthy local residents also spent their free time there. The taverns were managed by tax collectors who gathered tolls and duties, and they also hosted courts and other administrative functions [

14]. Gall Anonim, in his account of the death of Bolesław Chrobry in 1025, mentioned that “after his departure [the king] neither clapping nor the sound of the cittern was heard in the taverns” [

5,

14,

15].

In the 13th century, inns were planned along important trade routes, at crossroads, and in larger villages. Sometimes they were accompanied by a sawmill or a mill. Tavern keepers also engaged in trade, buying agricultural or livestock products, and selling small handmade goods to peasants [

6]. On Sundays and holidays, taverns transformed into places for dancing and celebrations. They hosted various events, courts, and village councils [

15]. According to the statute of the Bishop of Kraków, Jan Grot, from 1331, marriages conducted in taverns were considered illegal, indicating that weddings were held in taverns, alongside other ceremonies [

5].

The menu in early Polish taverns was quite simple. They served bread, lard, herring, cheese, and eggs. Occasionally, sausages and ham were available. The choice of beverages was also limited, with beer from royal or princely breweries, often poorly brewed for peasants. Better-quality beer, imported from cities, was served to wealthier guests. Vodka, either from royal estates or produced in-house, was available, but high-quality spirits, wine, or meads were rare [

6,

16].

In the 13th and 14th centuries, with the settlement of villages under German law, new types of taverns appeared—”sołtys” taverns. The tavern became an administrative center where the village leader (sołtys) collected rents, duties, held court, and imposed penalties. The leader of a newly founded village could establish a “free tavern”, a right to produce and sell alcoholic beverages, beer, and mead. The tavern was leased by the sołtys or managed by poorer peasants under the sołtys’s supervision. Apart from “sołtys” taverns, there were also parish taverns, where clergy leased the tavern or employed someone to run it for them. There were instances where the priest himself ran the tavern after mass, serving food and drinks to customers. Church authorities disapproved of priests running taverns and issued regulations forbidding them from working in parish taverns, serving guests, or even being present in them. Despite these prohibitions, parish taverns continued to operate until the end of the former Commonwealth, with a few lasting into the early 19th century [

5,

11,

14,

16].

Medieval taverns were usually larger than cottages but, like them, were made of wood and thatched. They were equipped with simple wooden tables, benches, and stools. It is unclear whether they already had a special table for serving food, which later became the buffet table [

5,

14,

16].

Larger taverns, like the “Budzyń” Tavern, had chambers or rooms that served as sleeping quarters for travelers and stables for horses [

5,

14].

Cheaper taverns were located on the outskirts of towns. Near the center, in the market, or along main streets, taverns were housed in brick buildings, which were much larger and more solid. The facilities in these places were certainly better than in the simple wooden taverns, and the range of meals and drinks served was more diverse, such as wine brought from Hungary [

5,

14,

17].

In the medieval tavern, social class boundaries were often blurred. Nobles, clergy, townsfolk, and peasants sat together at the same table, enjoying conversation and beer. However, there were places, especially in larger towns, where only the wealthier people—clergy, nobility, and the richest townspeople—could stay. Beggars, peasants, and poorer townsfolk were not tolerated in these taverns [

5,

14].

3.3. Taverns, Inns, and Stations in the 16th–19th Centuries

Significant changes in tavernkeeping took place in the second half of the 15th century due to the so-called “sołectwo acquisition”, which involved taking away the sołectwo (village leadership) from its current holders and incorporating it into noble estates. This led to the decline of the “sołtys” taverns and the “free taverns” run by peasants. Only two types of taverns remained in villages: estate taverns and parish taverns. In towns, alongside taverns owned by the mayor or starosta, there were also parish, monastic, and burgher taverns [

5,

14].

By the end of the medieval period, a system of “propinatory compulsion” existed in many areas, where subjects could only purchase alcoholic beverages produced by the manor or authorized leaseholders [

18]. In the 16th century and later, this “feudal compulsion” expanded. In many villages, it was considered one of the worst offenses to use a tavern other than the one prescribed by the lord. In some places, peasants caught using another tavern were punished by being dunked in icy water or kept in their underwear in a water barrel all day in freezing temperatures. There was also a “consumption compulsion”, where the serf population was required to buy a certain quantity of alcoholic beverages each year [

5,

16,

19].

Village tavernkeepers came from various national and social backgrounds. In the eastern parts of the former Commonwealth, Jews were primarily involved in running taverns, while on the western side of the Vistula, most tavernkeepers were Polish [

15].

Village taverns were usually located in the center of the village, sometimes even next to the church. However, taverns were also built at some distance from the village, along roads leading to the next town. This is why some taverns were located at the borders of villages, closer to busy roads [

5,

14].

Taverns located away from the village often had distinctive names based on the shape or color of the building, the owner’s name, or references to rest or revelry, such as Wygoda (Comfort), Radość (Joy), Rozkosz (Pleasure), Zgoda (Agreement), Czekaj (Wait), Poczekaj (Wait a bit), Uciecha (Delight), Ucieczka (Escape), Zabawa (Fun), Wesoła (Merry), Ostatni Grosz (Last Penny), Piekło (Hell), Sodoma (Sodom), Wymysłów (Whim), Nazłość (Anger), Wilcza Jama (Wolf’s Den). Some names referred to geographical locations, such as Rzym (Rome), Paryż (Paris), or Nowy Świat (New World). This is also how names for settlements near taverns were created [

5,

6,

14].

In the 19th century, traveling conditions were poor. Bad roads and horse-drawn vehicles made even short trips feel like expeditions requiring careful preparation. Stops were necessary, which is why taverns, inns, and similar establishments were almost an inseparable part of every journey. Their quality depended on the town’s location (lower standards in the eastern parts of the former Commonwealth) and distance from major routes. Taverns located along less-frequented roads mainly served alcohol and catered to local residents, sometimes lacking even a single guest room. In inns located on major communication routes, there could be several such rooms. It is also worth noting that sometimes transporters deliberately avoided main roads to protect the horseshoes from wear, which is why they ended up stopping at the most basic taverns [

20].

Taverns located along trade routes, called “gościńce” (guesthouses) or “zajezdne” (inns), in addition to the tavern, also had a “stan”. This was a stable with a cart shed where travelers could leave their horses or merchant carts. The “stan” could also be a separate building connected by a roof to the tavern. Sometimes it included a forge, where minor repairs could be made to carts and horses could be shod [

19]. Particularly in the lands east of the Vistula, taverns were often arranged with their wide front facing the road. A covered passage led through the middle to the “stan”, located at the rear of the building. More commonly, the “stan” was an extension of the main tavern building facing the road [

5,

18] (

Figure 1).

In towns frequently visited by travelers, large inns were built, which in the 18th century were referred to as “austerias” [

15]. A description of the austeria in the village of Dobra near Stryków in the former Łęczyca province from 1784: “A new austeria built in 1776 […] From this hall, there are doors to the tavern room […], where windows with small panes are set in wood. The brick stove is old, poor, and leaky. The floor and ceiling are in good condition. From this room, there are doors leading to the chamber […] This chamber has a window with six panes and a ceiling made of planks […] Across from the tavern room, there are two small rooms […] In one of the rooms, both the ceiling and floor are good, while in the other, only the ceiling is made of planks. The whole austeria is covered with shingles. Next to the austeria, there is a stable with a proper enclosure, in good condition, also covered with shingles, with six feeding racks” [

5].

In the Polish lands outside the borders of the former Commonwealth, particularly in Silesia, where timber was expensive, inns were built from stone or brick [

5,

14].

The inn was furnished with simple wooden tables, benches, and small tables. Tired travelers could find lodging in rooms or chambers. The rooms were equipped with wide benches for sleeping, and fresh straw was spread on the floor or the clay floor. For the nobility, fully equipped alcoves were available, containing wooden bedsteads with quilts and pillows. Besides tables and benches, the rooms also had wooden stools and a “szykwas”—a counter where mugs, glasses, and measures for vodka were placed [

19]. Baths were taken in a clay basin or under a well [

5,

14,

18].

The role of the inn in the life of the old village was still very important. The village court and local government met at the inn. The inn was also a place for selling products from farmsteads [

5,

14].

In establishments that hosted the nobility, better-quality beer, called “dubeltowe” (double beer), could be ordered. Its production took place in the manor brewery or it was brought in from the town. In the 18th century, beer was consumed almost with every meal, quenching thirst on hot days, and various types of tinctures were consumed in the winter [

5].

In the 16th century, the consumption of spirits began to spread in the Polish lands. Research by Z. Kuchowicz revealed that vodka, invented by Arabs in Morocco, which had an apothecary-like role there, later spread in Western Europe and then in Poland, Ukraine, Belarus, and Russia. Vodka was produced in rudimentary manor distilleries or breweries, made from grain, usually rye, and distilled in simple technical devices [

5,

14,

16]. In the countryside, efforts were made to get peasants to drink more. Low vodka prices led to high consumption. The effects of consuming high-proof vodka were more dangerous than drinking the previously consumed low-proof beer [

5,

15].

In the 16th–18th centuries, there were plenty of eating establishments in cities for both residents and travelers. Most of these were typical inns or taverns, called “szynki” in the 18th century (from the German word “schenken”—to pour), designed for the poorer social class. Alongside them, establishments of higher standards were created, sturdier, better-equipped, with a wider variety of menu options. City eateries, visited by wealthier clientele, had their own unique character. Some were famous for good honey, others for beer or wine, as well as for special dishes. In Warsaw and other larger cities, establishments for the wealthiest clients had luxurious, for the time, furnishings. They contained special rooms or alcoves, where expensive tapestries or carpets hung on the walls, tables were covered with tablecloths, and the furniture was upholstered. Especially in the second half of the 18th century, the standard of eating establishments in large cities greatly improved [

5,

14,

19].

In various parts of Poland, different models of village inns developed. Increasingly, private inns that were not owned by the manor were being built. Landowners either closed them down or sold them to professional innkeepers. The dominant model became the private inn owned by the innkeeper. In villages, inns were still run by Poles, but they were often replaced by wealthier German innkeepers, who had the support of the administrative authorities. In Galicia, regulations prohibited Jews from running village inns. However, this was only formal. In the Kingdom of Poland, matters concerning inns were of little importance to the authorities. A breakthrough came with the 1844 law, which introduced a high fee for vodka production. This led to the reduction of small distilleries. The law largely set the rules for alcohol consumption in inns and taverns. It allowed the sale of alcohol in licensed establishments only. Vodka could be sold, but not stronger than 46%. Inns had to close on Sundays before noon and after 10 p.m. It was prohibited to sell vodka on credit or with vouchers. Selling alcohol to intoxicated people was also forbidden [

5,

15].

In the Kingdom of Poland, most inns were located in wooden buildings. However, brick inns, much larger than before, were increasingly built. Most of them were guesthouses and inns, where travelers could find lodging and stables for horses. The furnishings were still modest, consisting of tables, benches, and stools. In alcoves designated for the higher classes, more expensive furniture was found. On Sundays and holidays, dances were held in village inns, and weddings, christenings, or wakes were organized [

5].

Józef Ignacy Kraszewski wrote that the inn is “a place for meetings, councils, and weddings, where everything is initiated and concluded, where one expresses sorrow to another, where people argue and fight, and reconcile—and love! The inn is the heart of the village” [

15].

Innkeepers rarely cared about properties that were not their own, trying to gain as much income as possible with minimal expenses [

20]. Therefore, it is difficult to talk about purposefully designed greenery around such buildings. It seems necessary for the surroundings to include a well with a crane or a river as a source of water. Some taverns had shady porches. If the inn was also the innkeeper’s residence, there might have been an orchard or vegetable garden on the property. Julian Ursyn Niemcewicz wrote: “it was decided to sleep in the courtyard, and I was sent under a pear tree by the fence” [

21]. Thus, there were also yards where horse-drawn vehicles were left. Perhaps also shaded by tree crowns, protecting from the sun and rain.

Images of old inns and the roads of the time can be found in newspapers (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3) and in guides (

Figure 4).

3.4. Red Inn in Lublin

3.4.1. Characteristics of the Area Under Study

The plot area is 0.38 hectares. Tourist Street surrounds the site from the southeast. To the northwest, the plot borders undeveloped lands in the Bystrzyca Valley. To the east, there is a large PGE network distribution station (

Figure 5). The area around the building is undeveloped, with 20 trees located on the site. There are as many as six advertising billboards on the property, which disrupt the visual aesthetics of the historic space. The area under study is not fenced, and there is no designated entrance. The building is listed in the register of monuments under number A/268 [

25]. It is worth emphasizing that one of the biggest problems of the sustainability project is the southern side of the tavern. The neighborhood across the street with parking areas or other modern constructions should also impose a curtain of vegetation on their green area surface.

3.4.2. Historical Outline

The inns in Lublin were owned by the Zaniewski, Lanckoroński, Bernardine, and Lublin council families. The privileged city inn was located in the city center, near the Town Hall [

4].

The first documented reference to an inn in Tatary appears in a privilege granted by King Sigismund I in 1515, which ordered that “only Lublin beer should be sold in this inn, so that the city fund would not be depleted”. At that time, the brewery belonged to the Lublin starost. This ban was likely not followed, as in 1532, the king ordered the closure of the inn, and a few years later, the refusal to execute the order was justified by the large income it generated for the city. The inn was then located along the route leading to Łęczna, a town known for its fairs at the time [

26]. This inn survived until the 17th century. It was probably made of wood and was completely burned down during the Deluge in 1660.

A 1786 inventory includes a note about the owner Jacek Twardowski. The document describes the building at that time, which was made of wood and had a passage hall and colonnades. Behind the entrance, through “double doors on wooden rails”, there was a large tavern room adjacent to an alcove, with a green tiled stove. The room’s equipment included a tavern table, pine benches, and stools. On the left side of the entrance, there was a “small shop, granary, and small brewery”, with a mud chimney and two stoves, along with a ruined beer-making trough. There was also a guest room with three windows, equipped with a stove, a bench under the window, a green tiled stove, a pine table, two cabinets, and shelves. In the rear of the building, there was a stable for five horses and a well with a wooden crane.

After the partitions, Tatary, as a royal domain, passed into the ownership of the Kingdom of Poland. In 1828, it was put up for public auction, and it was bought by Adam Count Pietrowicz Ożarowski, of the Rawicz coat of arms. The tympanum of the building bears the date 1833, which indicates its construction during Ożarowski’s time. The former inn was rebuilt into a new brick structure, along with the economic part, the well, and the stable. It was named “Czerwona Karczma” (Red Inn). The tympanum also bears the monogram FTU (currently unreadable). Unfortunately, it has not been determined whose initials these are [

26,

27].

The building, in the classicist style, was designed in the shape of a T. The front wing housed the residential and tavern sections. Next to it was a “stable”, which at the time contained boxes for horses and equipment [

27]. The location of the inn in the suburbs of Lublin is shown in plans from the early 19th century (

Figure 6 and

Figure 7).

In 1923, Kazimierz Graf initiated a project to adapt the building of the Czerwona Karczma into a nail and wire factory called “Tatary”. He submitted a proposal (

Figure 8) to the Construction Department of the Lublin Provincial Office [

27]. Along with Jan Koźmian and Tadeusz Dąbrowski, he formed a partnership. The project included converting the building into a production hall and adding an annex to the southeastern corner of the stables. The architect for the expansion was Bohdan Kelles-Krause. The plan marked the surroundings, including the orchard and arable fields. It is evident that a one-sided tree-lined avenue ran along the former Mełgiewska Street. The plan also shows embankments along the road and fields, with the inn located at their foot. Additionally, the plan marks a forge across from the inn at the intersection, which was to work in cooperation with the newly established factory.

In the 1930s, the factory was run by the Tuller brothers, but under their management, the factory struggled to prosper. The Tullers fell into debt and were involved in legal disputes with creditors and former employees. In 1938, in a petition to the District Court in Lublin, the co-owners of the company declared that the factory “ceased to exist and was completely liquidated several years ago”. In the Polish Monitor on 9 May 1939, it was publicly announced that the “Nail and Wire Factory ‘Tatary’, Graf, Dąbrowski, and Koźmian partnership” was struck off the commercial register on 9 December 1938.

After World War II, all taverns were given residential functions. A plan from this period shows the tavern located on Mełgiewska Street, near the meandering river and Słomiany Rynek (

Figure 9). A fire in 1952 destroyed the building, especially the stable section [

27].

After 1945, the building was nationalized and used as municipal housing for the poorest families. Until 2016, it was used as a residential building. At that time, due to the very poor technical condition of the building, the last residents were evicted, and the windows and doors were bricked up.

Following 1945, the building was nationalized and repurposed as municipal housing for low-income families. It remained in residential use until 2016, when, due to its severely deteriorated technical condition, the last occupants were relocated. Subsequently, the building was secured by bricking up its windows and doors.

3.4.3. Degree of Protection of the Building and Its Adjacent Area

The overall condition of the inn building is poor (

Figure 10,

Figure 11,

Figure 12 and

Figure 13). The foundations and walls are damp, and in some places, there is mold. The roof covering consists of damaged sheet metal in places. The windows and doors have been bricked up. The exterior elevations are partially missing plaster, revealing the materials used for the wall construction (stone and brick). The original pattern of the exterior elevation has been preserved. The doors to the entrance hall, which are significantly damaged but likely original, were removed in 2016. On-site, signs of vandalism, break-ins, and theft of electrical cables are noticeable.

The tree stand around the Red Inn in Lublin consists of 20 trees (

Figure 14). In terms of quantity, the most common species are as follows:

Prunus domestica subsp.

syriaca (five trees),

Tilia cordata (four trees),

Acer platanoides (two trees),

Rhus typhina (two trees), and

Fraxinus pennsylvanica Marschall (two trees). Other species include the following:

Populus symonii (one tree),

Pinus sylvestris L. (one tree),

Syringa vulgaris (one tree),

Acer negundo (one tree), and

Malus (one tree). There is also a group of shrubs consisting of

Sambucus nigra,

Prunus domestica subsp.

syriaca,

Prunus cerasus, and

Acer negundo. Five trees in poor health should be removed. The remaining trees are in good to very good condition but require maintenance work. Most of the trees are between 40 and 70 years old, with two specimens approximately 100 years old—

Tilia cordata and

Acer platanoides. These trees likely come from plantings made during the adaptation of the inn to a wire factory. A large

Acer platanoides shows signs of being set on fire, so sanitary pruning should be carried out. Four trees have bird nests.

3.4.4. Social Research—User Needs Analysis

The analysis of user needs was conducted among 60 people from different age groups living in the immediate vicinity of the studied area. Each person was asked eight survey questions. The analysis of the conducted research revealed the following problems.

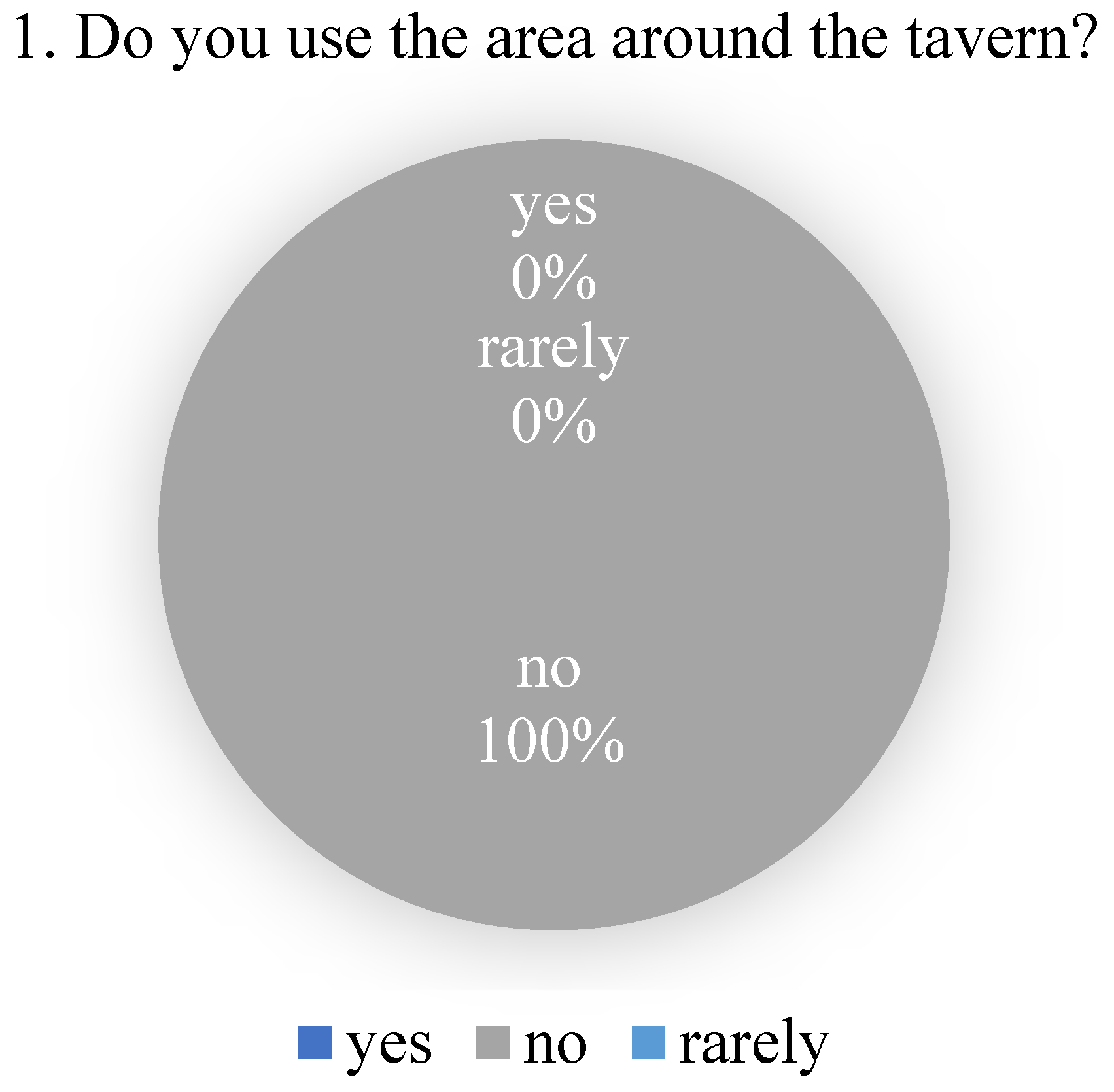

The respondents unanimously indicated that they do not actively utilize the studied area. The site is perceived as a neglected wasteland and is generally avoided due to the presence of homeless individuals, overgrown vegetation, and a perceived sense of insecurity (

Figure 15).

As many as 67% of respondents believe that the current development of the area is very bad, and 23% of respondents claim that the area is “averagely” developed. Individuals stated that the area is well or very well developed and do not want changes (

Figure 16).

Among the most frequently indicated expectations regarding the future development of the Red Tavern site, 40% of respondents expressed a preference for its transformation into a recreational area. The second most common response, indicated by 27% of participants, also emphasized the need for recreational functions, highlighting a strong demand for leisure-oriented spaces. Additionally, 17% of respondents favored an aesthetically enhanced development of the site. A cultural function was proposed by 10% of those surveyed, while only 6% identified an ecological function as a priority for the area (

Figure 17).

The most frequently chosen answer regarding the function of the place studied was the answer “a meeting place for the local community” by as much as 54%. The second most frequently chosen option regarding the function of the facility chosen by the respondents was the decision to create a place for passive and active recreation. A total of 13% of the respondents agreed with all of the listed functions. The smallest group of people decided to create a facility for organizing festivals or picnics in the place studied (

Figure 18).

5. What problems do you consider to be the most important to solve in the area covered by the survey?

The most common answers to the question about the problematic nature of the area surveyed included the following: the presence of homeless people living in the Czerwona Karczma building, the dilapidated building and the danger of staying there, untamed vegetation, a busy road, street noise, and poor lighting, which affects safety late at night.

When asked about the condition of the greenery around the facility, the majority of respondents responded that it was in good condition—56%. A total of 17% of respondents gave a very good opinion. Among the survey participants, 17% did not have a specific answer about the condition of the greenery, or it was difficult for them to determine it. A total of 7% of respondents believe that the greenery is in poor condition, and 3% that its condition is very poor (

Figure 19).

7. What investments do you think should be made in this area?

The respondents answered that the building of the Red Tavern could house: a kindergarten for children, a library, a restaurant, a place of integration for young people, and a place associated with Bystrzyca, e.g., a marina for kayakers.

8. What elements of the Red Tavern area should be changed?

The respondents answered that the billboards should be removed and better lighting should be installed near the building, which will affect safety in the area. The Red Tavern building should be renovated and the area around it should be developed into a place of recreation.

The conversations and observations we conducted not only helped identify the problems of the place but were also a form of social participation—they gave people a sense of influence on the space. They facilitate the acceptance of the project in the future and will probably reduce the risk of social resistance. The involvement of residents in designing the gardens around the historic inn increases the chances that they will not destroy or vandalize it but will use it in accordance with its intended purpose.

It is worth emphasizing here that not every revitalization intervention automatically translates into an improvement in the quality of life of all residents. Although the goal of revitalization is often to revitalize degraded urban areas by improving infrastructure, aesthetics, and functionality of space, this process can also have negative social consequences, such as gentrification [

31,

32].

Gentrification is a phenomenon of gradual displacement of previous—often poorer—residents from areas subjected to revitalization as a result of increased living costs (rents, services, real estate), the emergence of new social groups with higher incomes and changes in the nature of the space. As a result, social polarization, loss of local identity, and deterioration of living conditions for the weakest social groups can occur [

33,

34].

Therefore, social research conducted before, during, and after revitalization is crucial. It allows for the identification of the real needs of local communities, assessment of social risks, and ensures that interventions will support inclusive development and not exclusion. Ignoring the voices of residents can lead to aesthetically attractive but socially harmful projects.

The renovated inn as a place can improve the quality of life in the district, but under certain conditions. The positive effects of tourism on the quality of life in the district include economic revival—new jobs will be created in services and gastronomy. Investments in infrastructure will be made—better lighting and landscaped green space—a benefit for both tourists and residents. The aesthetics and safety of the district will improve. Perhaps we will observe an increase in the sense of local pride. The renovated historical inn (one of its kind in Lublin) is a promotion of local culture, heritage, and the identity of the district. The renovation of the facility can improve the quality of life in the district, but only if it is developed in a sustainable, participatory manner and with respect for the local community. The key is to manage tourism in a way that brings lasting benefits to residents, not just profits to the private investor.

Lublin, in 2025, will experience dynamic development in both the tourism and urban planning sectors. The city is becoming increasingly attractive to visitors, while investing in infrastructure and urban space, which improves the quality of life of its residents. In 2024, Lublin was visited by nearly 2 million tourists, which is a record in the city’s history. Such an increase in interest translates into the development of the local economy, especially in the services, gastronomy, and culture sectors. The increase in the number of foreign tourists is particularly noticeable—by 85 thousand, to a total of 428 thousand people. Lublin was distinguished by the British daily The Independent as one of five cities in the world worth visiting in 2025 [

35]. Its authentic climate, rich history, and unique atmosphere were emphasized. Lublin focuses on sustainable development, combining tourist functions with the needs of the local community. The city plans investments in infrastructure, such as modernization of buildings, improvement of energy efficiency, and creation of new public spaces. The GPR also includes social activities aimed at activating residents and supporting groups at risk of exclusion. Numerous investments are planned within the 2025 budget, including the implementation of the Riverside Park project. The Riverside Park project in Lublin involves the creation of a new recreational area along the Bystrzyca River, covering over 70 ha. The park will feature a riverside beach, pedestrian and bicycle paths, a dog run, and footbridges with viewing points. The inn is located in close proximity to the Bystrzyca River (150 m) [

36]. It is true that work is currently underway in another section of the riverbed, but in the next few years, there are plans to also modernize the riverbank near the inn.

Currently, the Red Inn belongs to the city of Lublin. However, the property is up for auction with a starting price of PLN 2.9 million (approx. EUR 700,000). The cost of renovating a historic building in Poland can vary significantly depending on the following: the type and technical condition of the building, its size, the scope of required conservation work, the materials and technologies used, and the arrangement of the building’s surroundings. The approximate cost of renovating a historic building such as the inn will be approx. PLN 10 million (EUR 2.4 million). Owners of historic buildings can apply for the following:

subsidies from the state budget (Ministry of Culture and National Heritage),

funds from the provincial conservator of historic buildings,

municipal and city funds,

funds from the EU (e.g., regional programs, reconstruction assistance for the cohesion and territories of Europe, European Funds for Infrastructure, Climate, and Environment),

support from the National Heritage Institute or the Foundation for Polish Cultural Heritage.

3.4.5. Summary of the Revaluation and Proposed Revitalization Project for the Tavern Area

In summary, the proposed project combines historical preservation, community development, and environmental sustainability to create a revitalized space that honors the past while serving the needs of modern-day residents and visitors. The Red Inn will once again become a significant landmark in the area, offering a blend of history, culture, and nature.

Historical Background and Building Features:

The Red Tavern has a rich history, originally serving as a tavern located near the Bystrzyca River. It became part of the local industrial heritage in the early 20th century when it was adapted for use as a nail and wire factory by Kazimierz Graf.

The structure, built from white stone and brick, features characteristic elements such as wooden floors, brick vaulting in the basement, and a characteristic roof covered with holenderka tiles. It is a protected historical site, having been listed in the Register of Historical Monuments in 1967.

Social and Acoustic Issues:

The area surrounding the tavern is currently not actively used. It has been marked as unsafe and neglected, with residents of the neighborhood expressing concerns about the presence of homeless people, overgrown vegetation, and safety risks.

The tavern is located near a busy road, Turystyczna Street, which causes high traffic noise. This calls for the introduction of noise barriers, such as multi-tiered greenery, to reduce the impact of traffic on the area. Furthermore, the project’s design emphasizes a solution for better street lighting and improved safety.

Proposed Revitalization:

Architectural renewal: The proposed project includes restoring and adapting the Czerwona Karczma building into a cultural and gastronomic center, bringing back traditional Polish cuisine. The menu would feature old Polish dishes such as “bigos hultajski” and “pierogi”, reflecting the region’s rich culinary history.

Public space and greenery: The design integrates both aesthetic and functional elements, including the reconstruction of the French herringbone pattern (jodełka) previously seen in the tavern’s entrance gates. The surrounding area would be revamped to include pedestrian pathways with permeable HanseGrand surfaces, eco-friendly parking, and a surrounding greenery zone with native shrubs and trees like linden (Tilia cordata) and hawthorn (Crataegus). This greenery will help reduce noise levels from the street and offer a serene environment (

Figure 20,

Figure 21 and

Figure 22).

Cultural engagement: The area would also include outdoor spaces for social activities, such as a shaded café garden with string lights and an interactive play area for children. Additionally, historical elements related to the Bystrzyca River will be integrated into the design, perhaps even creating a small space dedicated to water-related activities, such as kayaking. In addition, within the general framework of the project, small workshops for the production of household items for children, adults, and seniors, including pottery and pottery painting, can be organized.

Environmental design: Native plants, especially those attractive to wildlife like bees and birds, will be planted. Flower beds and berry bushes will be included to enrich the ecosystem, contributing to biodiversity and offering the local community a natural space for relaxation. The development of the area and the reintroduction of native species of trees and shrubs around monuments in Lublin is an action that can combine the protection of cultural heritage with pro-ecological activities. The project proposes native species such as English oak or common rowan, coral viburnum, and common dogwood. Low greenery is planned under the trees and shrubs—perennial flower beds, the main entrance is highlighted by rows of trees, and the garden is protected from street noise thanks to hornbeam and yew hedges. New benches and rest areas have been placed overlooking the monument. Permeable surfaces have been used (e.g., gravel, lawn slabs). There is a huge parking lot in the vicinity on the south side; therefore, it is suggested to cooperate with the owner of the neighboring plot to plant it with greenery such as climbers and trees with wide crowns.

Vision for the Future:

The Red Inn will be transformed into a community hub that promotes both local culture and historical awareness, giving residents and visitors alike a chance to experience the heritage of the Lublin region in a contemporary setting. The area will also offer recreational spaces, fostering social interactions and promoting community activities.

Long-Term Impact:

The revitalization of the area is part of a broader vision to restore the cultural heritage and improve the quality of life for the surrounding neighborhoods. Not only will this attract local residents, but it will also create a unique cultural and historical destination for tourists. Additionally, it will enhance the ecological balance of the area, turning a once-neglected part of the city into a vibrant space for all.

Figure 20.

Revitalization project of the surroundings of the Red Inn in Lublin (prepared by P. Golianek, M. Dudkiewicz).

Figure 20.

Revitalization project of the surroundings of the Red Inn in Lublin (prepared by P. Golianek, M. Dudkiewicz).

Figure 21.

View of the relaxation area—under the trees with hanging light garlands, surrounded by colorful perennial flower beds (prepared by P. Golianek).

Figure 21.

View of the relaxation area—under the trees with hanging light garlands, surrounded by colorful perennial flower beds (prepared by P. Golianek).

Figure 22.

View of the playground with a grassy surface and wooden recreational equipment. Nearby, a group of lilacs in the ‘Paul Deschanel’ variety with an intense fragrance is planned. A large maple tree provides shade from excessive sunlight.

Figure 22.

View of the playground with a grassy surface and wooden recreational equipment. Nearby, a group of lilacs in the ‘Paul Deschanel’ variety with an intense fragrance is planned. A large maple tree provides shade from excessive sunlight.