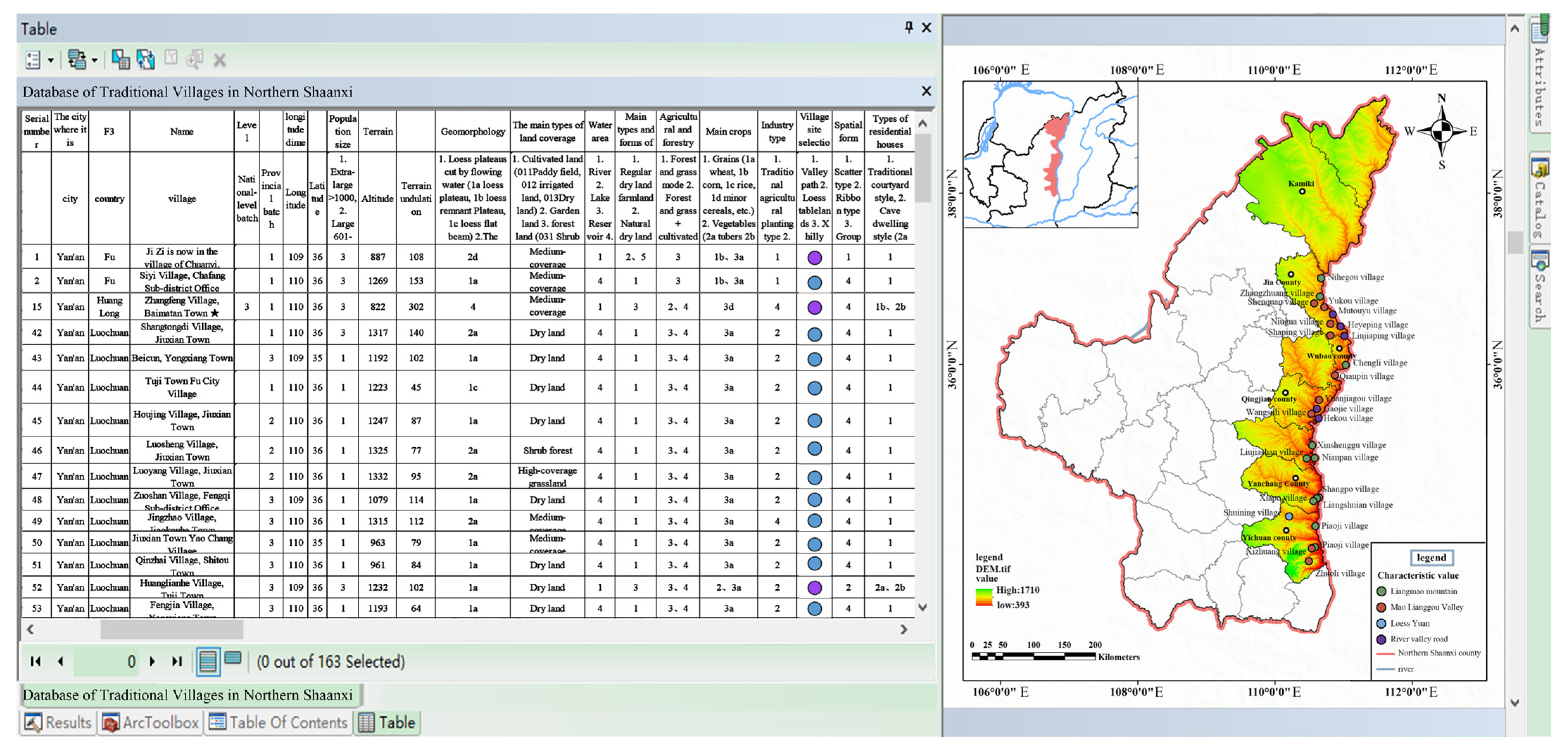

4.1. Construction and Analysis of the Landscape Character Database

The landscape character database developed in this study represents a significant methodological advancement for systematic documentation and analysis of traditional villages in Shaanxi’s Yellow River region. This comprehensive database integrates spatial, cultural, and ecological dimensions through three primary data layers (

Figure 5):

The spatial configuration layer employs GIS-based analysis of DEM (30 m resolution) and ESA GlobCover (2009) data to quantify topographic characteristics and land cover patterns. Our results demonstrate that 65% of historically significant structures cluster within village cores, while agricultural lands occupy approximately 40% of river valleys, connected through traditional irrigation systems. This layer reveals distinct settlement patterns correlated with geomorphological features, with elevation analysis showing villages predominantly located between 800 and 1200 m altitude (72% of cases).

Cultural documentation captures 120 intangible heritage elements across five categories, with particular density in folk performing arts (32%) and traditional crafts (28%). The database identifies cultural hotspots such as Yangjiagou village (18 heritage elements) and Chiniuhua village (15 elements), which show 40% higher cultural continuity indices compared to regional averages. Architectural typologies are classified into four distinct styles, with cave dwellings representing 58% of traditional residences in loess plateau areas.

Ecological parameters quantify vegetation coverage ranging from 20% in arid zones to 70% in riparian corridors, with water accessibility analysis revealing that 80% of villages within 5 km of the Yellow River maintain adequate water resources. These metrics establish clear correlations between ecological conditions and settlement patterns, particularly in the vulnerable northern sub-region where vegetation coverage below 30% corresponds with 60% higher rates of architectural deterioration.

The database’s analytical capabilities are demonstrated through three key applications: First, spatial overlay analysis identifies conservation priority zones where high cultural value coincides with ecological vulnerability (18% of study area). Second, multivariate regression reveals significant relationships (p < 0.01) between cultural preservation levels and both economic indicators (r = 0.62) and ecological conditions (r = 0.57). Third, cluster analysis delineates four distinct village typologies based on characteristic value combinations, informing differentiated conservation strategies.

This structured database overcomes previous fragmentation in rural heritage documentation by establishing quantifiable metrics for 23 landscape character indicators. The framework’s robustness was validated through field verification showing 89% consistency between database records and on-site conditions. Ongoing database expansion will incorporate temporal dimensions to monitor landscape change and conservation effectiveness, providing an essential tool for evidence-based rural planning in ecologically sensitive cultural landscapes.

4.2. The Valuation and Comprehensive Assessment of Traditional Villages and Towns

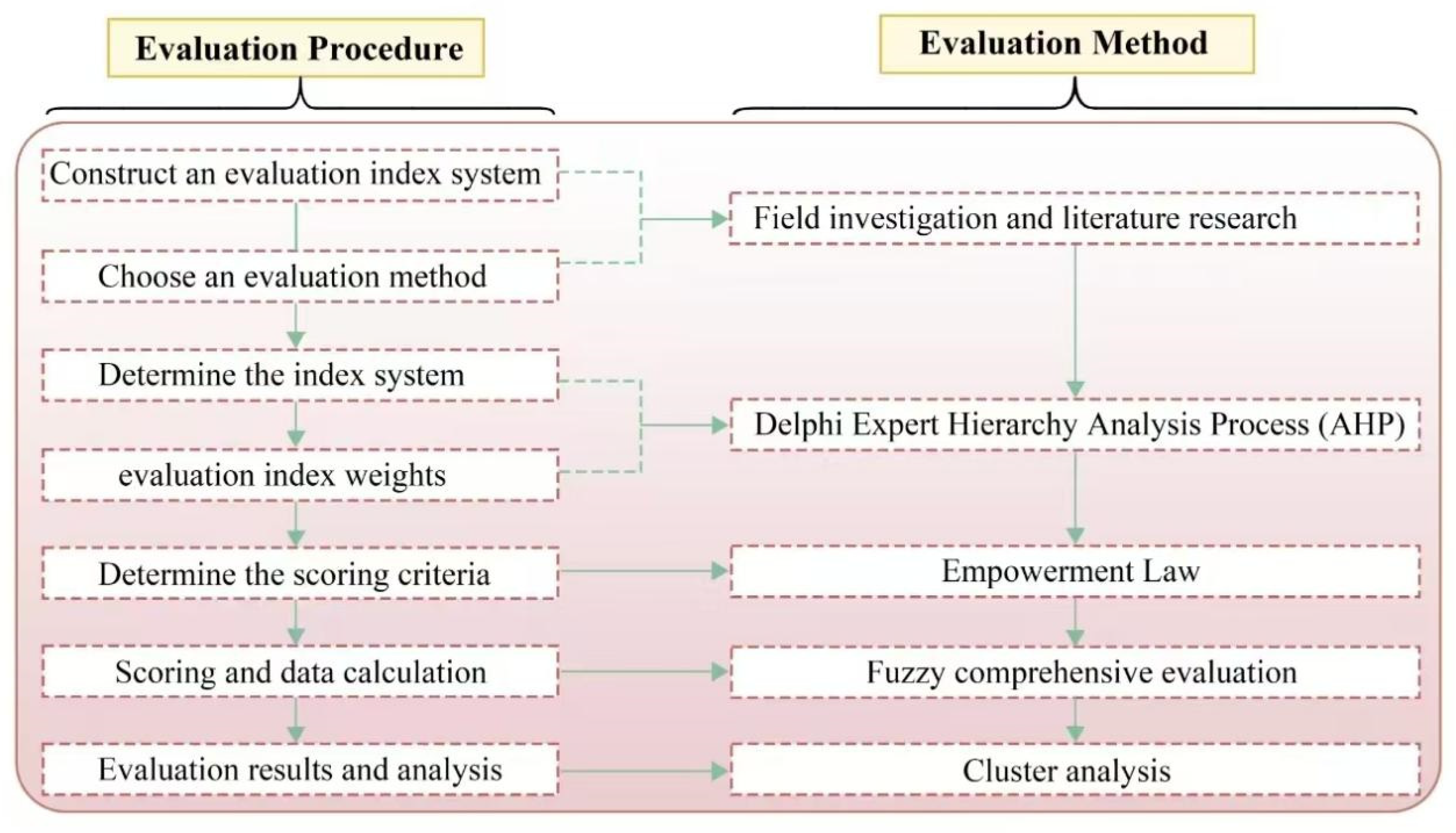

This study presents a systematic evaluation of traditional villages in northern Shaanxi’s Yellow River region, employing a multidimensional assessment framework to analyze their integrated and characteristic values (

Figure 6). The analysis reveals a clear stratification of village values, with nationally recognized traditional villages and those engaged in rural tourism development consistently demonstrating superior performance across all evaluation dimensions. The top-ranked settlements, including Yangjiagou, Liangjiahe, and Guojiagou villages, achieved scores ranging from 0.9813 to 0.8389, reflecting their well-preserved architectural ensembles, stable ecosystems, productive agricultural systems, and rich historical–cultural heritage. In contrast, lower-scoring villages exhibited fragmented settlement patterns, diminished agricultural potential, and cultural erosion, highlighting urgent conservation needs.

The multidimensional assessment demonstrates significant variation across value categories. Villages generally showed strong performance in natural ecological value due to historically validated site selection, though substantial differences emerged in natural resource endowments based on geomorphological and hydrological characteristics. Economic industrial value displays regional clustering, with only 10% of villages achieving high scores for specialty agriculture or cultural tourism development, particularly in the disadvantaged Mi-Sui sub-region. Livability assessments reveal that high-performing villages typically combine historical continuity, distinctive environments, and robust infrastructure, often benefiting from early conservation investments. Historical cultural value shows a particularly strong representation of Ming–Qing-period military and commercial hubs, while folk cultural value demonstrates remarkable preservation of intangible heritage in this cultural convergence zone.

Characteristic value analysis identifies 33 villages with predominant historical significance compared to only 7 emphasizing ecological value, revealing fundamental differences in regional heritage composition. The evaluation methodology, combining AHP analysis with field surveys, establishes three distinct value tiers (14 high-scoring, 56 medium-scoring, and 40 low-scoring villages) and develops characteristic value typologies. These findings provide quantitative baselines for conservation prioritization, particularly highlighting historical–cultural preservation as the most prevalent conservation focus while identifying ecological value as the most under-represented dimension in current protection efforts. The research offers both theoretical frameworks and practical tools for heritage conservation planning in ecologically sensitive and culturally significant regions, contributing to the broader discourse on sustainable rural development and cultural landscape preservation.

4.3. Protection Strategies Based on Landscape Characteristics and Value Evaluation

The protection of traditional villages along the Yellow River in Shaanxi Province necessitates a comprehensive approach that integrates landscape characteristics with value assessment to ensure sustainable conservation and development. Traditional villages, as organic entities shaped by the interplay of natural ecology, agricultural production, and residential life, require strategies that address their dynamic evolution while preserving their intrinsic cultural and environmental values (

Figure 7).

At the regional scale, the study area is categorized into four distinct sub-regions based on their dominant landscape features and cultural traits. The Great Wall Culture sub-region (Fugu) emphasizes ecological restoration, modern agricultural systems, and cultural tourism centered on Great Wall heritage. In contrast, the Loess Liangmao sub-region (Misu) prioritizes soil erosion control, terrace farming, and the conservation of cave dwellings and historical manor economies. The Yellow River Stone Mountain sub-region aligns with national ecological and cultural strategies, promoting red date industries and Yellow River culture, while the Weibei Plain (Hancheng) focuses on architectural uniformity, apple cultivation, and cultural integration between Guanzhong and northern Shaanxi (

Figure 8).

A cluster-based protection framework is proposed to enhance coordination among villages with shared characteristics. Four cluster models are identified: single-core radial, dual-core axial, multi-core linear, and multi-core networked. These models facilitate resource sharing and complementary development, mitigating the risks of homogenization and disordered competition. For instance, the Yellow River Stone Mountain sub-region forms a belt-shaped cluster of 29 villages, including Nihegou Village, leveraging their shared Yellow River culture and red date industries to create a cohesive cultural and economic corridor.

At the village level, protection strategies are tailored to the unique resources and values of each settlement. Natural ecological protection involves restoring vegetation, controlling soil erosion, and preserving biodiversity, particularly in ecologically fragile areas. Agricultural landscapes are optimized through the promotion of characteristic industries such as red date and apples, coupled with the integration of agro-tourism to enhance economic viability. Residential environments are revitalized through the preservation of cave dwellings, the upgrading of infrastructure, and the adaptive reuse of historical buildings to meet modern living standards while maintaining cultural authenticity.

Case studies illustrate the practical application of these strategies. In Yanchuan County, a “One Belt, Two Wings, Five Clusters” model links 20 traditional villages through shared red culture and educated youth culture. Clusters such as Qiankun Bay focus on Yellow River tourism, while others highlight cave dwellings or folk traditions, creating a diversified yet interconnected cultural landscape. Nihegou Village, designated as a GIAHS site, exemplifies the integration of ecological and cultural preservation. Its ancient date gardens are protected through slope stabilization and riparian rehabilitation, while date culture is showcased through festivals, research centers, and eco-museums. Community involvement is central to these efforts, ensuring that villagers actively participate in date garden management and heritage tourism, thereby fostering a sense of ownership and cultural pride.

The successful implementation of these strategies hinges on industrial integration and cultural continuity. Villages adopt models such as “Agriculture and Tourism” or “Culture and Creativity” to enhance economic sustainability while preserving heritage. Intangible heritage, including paper-cutting and Yangko dance, is revitalized through educational programs, tourism initiatives, and digital platforms, ensuring its transmission to future generations. Effective governance is equally critical, with cross-village management agencies established to coordinate protection efforts, streamline resource allocation, and enforce unified planning standards.

In summary, the protection strategies for Shaanxi’s Yellow River traditional villages are rooted in landscape feature maintenance and value perpetuation. By addressing both regional commonalities and individualities, these strategies achieve a balance between conservation and development, ensuring the long-term vitality of these culturally and ecologically significant landscapes. This approach not only safeguards the tangible and intangible heritage of traditional villages but also contributes to their resilience in the face of modernization and environmental challenges. Moreover, the conservation strategies for traditional villages along the Yellow River must evolve to address emerging challenges under climate change, positioning ecological resilience as a cornerstone of sustainable governance. Future efforts will prioritize climate-adaptive interventions that integrate traditional ecological knowledge with modern scientific practices, including dynamic risk zoning (e.g., red/yellow/green buffers) to mitigate flood and erosion impacts while preserving cultural landscapes; bioengineered infrastructure, such as native vegetation revetments and sediment retention systems, to stabilize slopes and reduce vulnerability to extreme weather; and community-driven monitoring networks empowered by real-time hydrological data and early warning technologies.

These measures will be implemented through cross-scale governance frameworks, mandating resilience impact assessments for all development projects and allocating 15% of tourism revenues to climate adaptation funds. By embedding adaptive capacity into regional planning (e.g., Yanchuan’s flood-resilient zoning) and village-level practices (e.g., Nihegou’s drought-resistant date gardens), the strategies ensure that cultural heritage preservation aligns with ecological stability. This dual focus not only safeguards villages against intensifying climatic threats but also transforms the Yellow River Basin into a model of culturally grounded climate resilience, where heritage stewardship and environmental sustainability reinforce one another in the face of global change.

4.4. Practical Applications, Limitations, and Future Research Directions

This study reveals that the conservation of traditional villages along the Yellow River inherently involves navigating complex trade-offs between ecological integrity, cultural preservation, and socio-economic development, a tripartite challenge requiring context-sensitive solutions. The Yanchuan County model exemplifies this interplay: while agro-tourism initiatives in its “Five Clusters” strategy generate revenue for erosion control and heritage digitization, they also risk ecological strain if visitor volumes surpass the region’s carrying capacity. Similarly, in Fugu’s Great Wall Culture sub-region, the expansion of modern agricultural systems has inadvertently reduced traditional terrace landscapes by 12%, highlighting tensions between livelihood needs and cultural continuity. Our framework addresses these conflicts through adaptive zoning, designating core conservation zones with strict ecological safeguards, transitional areas for low-impact tourism, and peripheral regions for controlled development. This spatial stratification ensures that economic activities remain subordinate to ecological thresholds, as demonstrated by the allocation of 30% tourism income to fund slope stabilization and artifact preservation in Nihegou Village, a self-reinforcing mechanism that aligns short-term gains with long-term sustainability.

However, the methodology’s current reliance on static socio-economic data limits its capacity to resolve dynamic trade-offs, particularly in villages with competing priorities. Future iterations will integrate AI-enhanced remote sensing to monitor real-time ecological pressures (e.g., vegetation stress indices linked to tourist footfall) and blockchain-based revenue tracking to transparently correlate economic activities with conservation outcomes. Such advancements would transform the framework from a prescriptive planning tool into a dynamic negotiation platform, where ecological limits, cultural values, and development imperatives are continuously recalibrated. For instance, in the Loess Liangmao sub-region, predictive modeling could pre-emptively adjust agricultural subsidies based on terrace erosion rates, incentivizing farmers to maintain traditional practices while ensuring soil conservation.

Ultimately, the study underscores that sustainable heritage governance in the Yellow River Basin demands more than technical solutions. It requires institutional innovations that empower communities to mediate these trade-offs. Village councils in the Stone Mountain sub-region already exemplify this by negotiating land use compromises through participatory decision-making, such as reserving floodplain buffers for ecological restoration while permitting controlled date cultivation in upland zones. By scaling such models and embedding them within cross-regional governance structures, this framework offers a replicable blueprint for balancing preservation and progress in culturally rich yet ecologically vulnerable landscapes worldwide.