Spatial Differentiation Characteristics and Influencing Factors of Public Cultural Facilities in Xinjiang

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

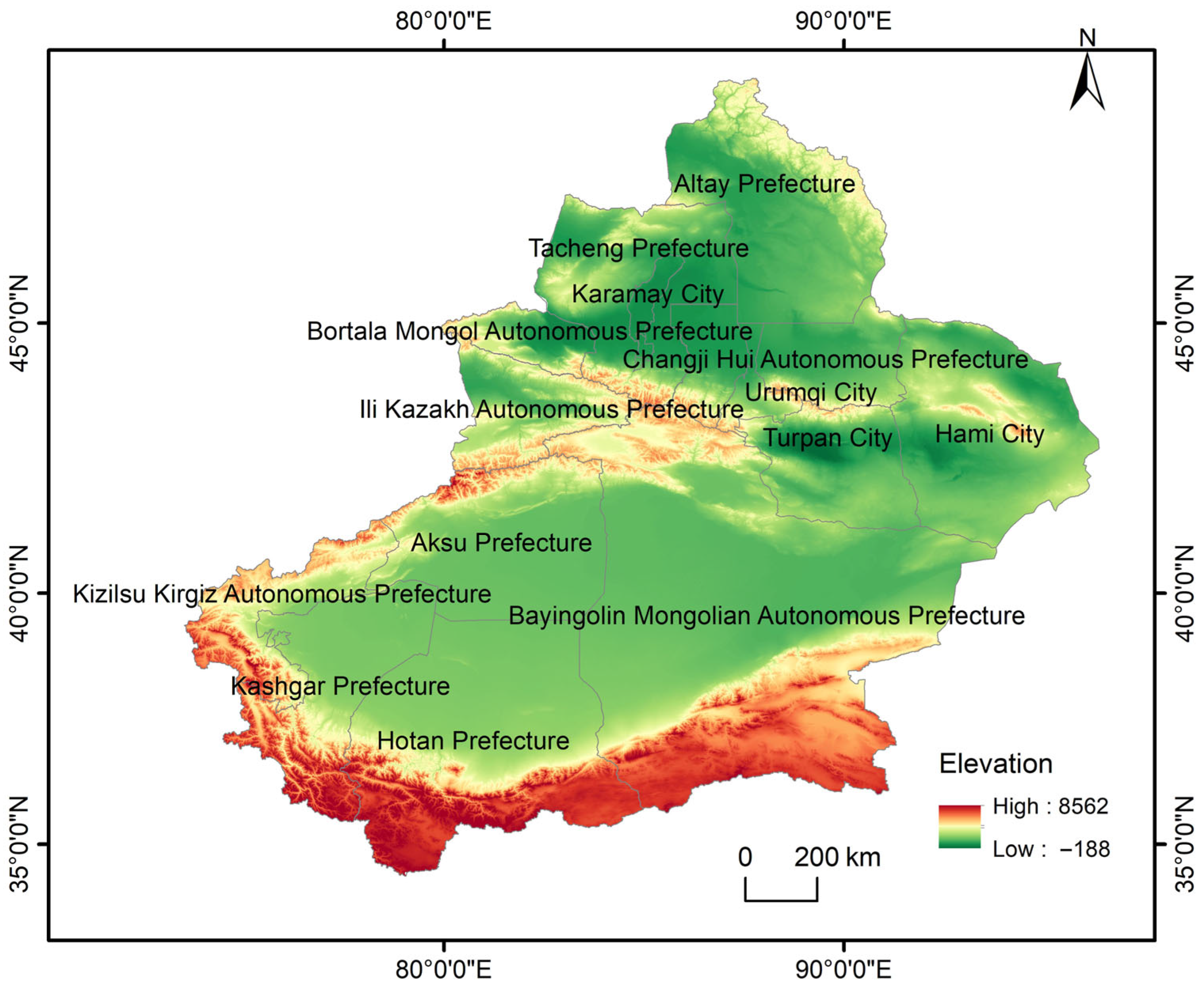

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Sources

2.3. Research Methods

2.3.1. Nearest Neighbor Index

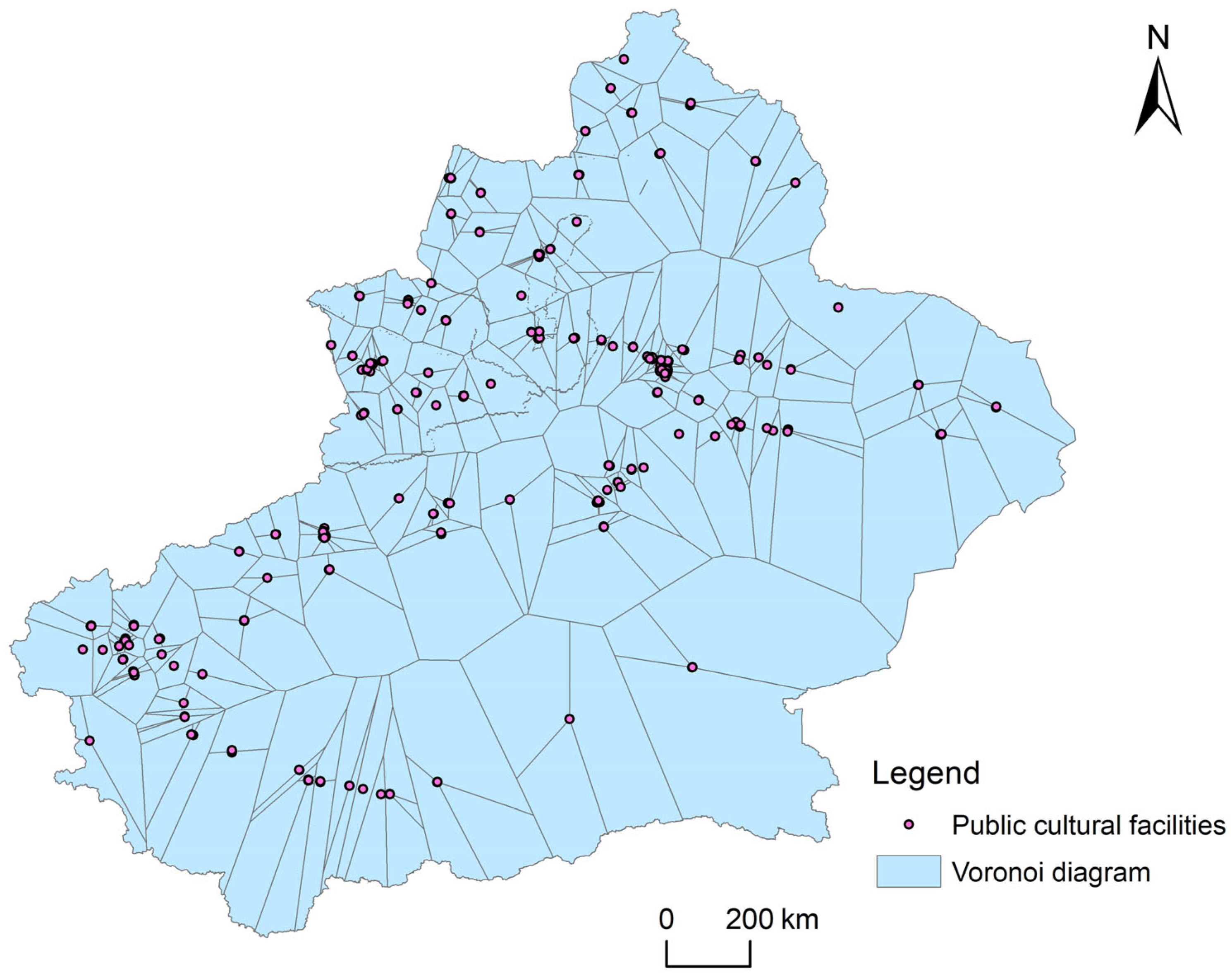

2.3.2. Thiessen Polygons

2.3.3. Disequilibrium Index

2.3.4. Kernel Density

2.3.5. Geodetector

3. Results

3.1. Spatial Differentiation Characteristics of Public Cultural Facilities in Xinjiang

3.1.1. Spatial Quantity Characteristics

3.1.2. Spatial Distribution Type

3.1.3. Spatial Distribution Equilibrium

3.1.4. Spatial Distribution Density

3.2. Measurement of Equalization Level

3.2.1. Analysis of Geographical Density Equalization

3.2.2. Analysis of Equalization of per Capita Quantity

3.2.3. Dual-Dimensional Regional Equalization Classification

3.3. Influencing Factors of the Spatial Distribution of Public Cultural Facilities in Xinjiang

3.3.1. Selection of Indicators

3.3.2. Factor Detection

3.3.3. Interactive Detection

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jennings, V.; Larson, L.; Yun, J. Advancing Sustainability through Urban Green Space: Cultural Ecosystem Services, Equity, and Social Determinants of Health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2016, 13, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burlacu, S.; Rădulescu, C.-V.; Bălu, E.P.; Dobre, F. Socio-Cultural Sustainability for Resilience in Public Services: Strategies for Achieving Inclusive and Equitable Service Delivery. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. 2023, 12, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Moon, J. Analysis of Urban Spatial Accessibility of Museums within the Scope of Seoul. Buildings 2022, 12, 1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, X.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, Y. Can the National Public Cultural Service System Demonstration Zone Promote the Sustainable Development of Urban Culture? Sustainability 2024, 16, 9323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguome, N.M.; Ewurum, N.I.; Ifeanacho, K.P.; Abaa-Okorie, L.C.; Ugwu, C.G. Public recreational facilities as catalyst for urban aging-in-place decision in developing countries. Cities 2024, 155, 105448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouratidis, K. Urban planning and quality of life: A review of pathways linking the built environment to subjective well-being. Cities 2021, 115, 103229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Ma, L.; Tao, T.; Zhang, W. Do the supply of and demand for rural public service facilities match? Assessment based on the perspective of rural residents. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 82, 103905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero-Jauregui, C.; Arnaiz-Schmitz, C.; Herrera, L.; Smart, S.M.; Montes, C.; Pineda, F.D.; Fe Schmitz, M. Aligning landscape structure with ecosystem services along an urban-rural gradient. Trade-offs and transitions towards cultural services. Landsc. Ecol. 2019, 34, 1525–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, X.; Tang, L.; Wei, X.; Li, Y. Spatial interaction between urbanization and ecosystem services in Chinese urban agglomerations. Land Use Policy 2021, 109, 105587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariano, R.; Vårheim, A. Libraries, museums and cultural centers in foreign policy and cultural diplomacy: A scoping review. J. Doc. 2022, 78, 651–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Liu, M.; Hu, X.; Guo, X. Temporal and spatial evolution of Chinese museums and their causes analysis. Trop. Geogr. 2022, 42, 469–480. [Google Scholar]

- Pfeifere, D. The issues of defining and classifying cultural centres. Econ. Cult. 2022, 19, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Jiang, G. Construction and planning of library service facilities system based on public digital culture education in international cultural metropolis. Open House Int. 2019, 44, 64–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Ma, R.; Luo, M.; Wu, L.; Fu, W. An Identification Method of the Externality of Cultural Facilities from the Perspective of Spatial Distribution of Cultural Industry: A Case Study of Ningbo, China. Buildings 2023, 13, 692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z. Exploring the spatial dynamics of cultural facilities based on multi-source data: A case study of Nanjing’s art institutions. Open Geosci. 2023, 15, 20220532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad, J.; Jung, C. Extracting the Planning Elements for Sustainable Urban Regeneration in Dubai with AHP (Analytic Hierarchy Process). Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 76, 103496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; He, J.; Li, Q. Research on the suitability of urban cultural facilities supply and demand based on multi-source data. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Smart Transportation and City Engineering (STCE 2023), Chongqing, China, 16–18 December 2023; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2024; Volume 13018, pp. 1094–1100. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, S.; Wei, Z. Planning for Public Cultural Facilities in the Municipal Area from the Perspective of Territory Planning. ICCREM 2024 2025, 1201–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Huang, Q.; Yang, H. Supply-demand spatial patterns of park cultural services in megalopolis area of Shenzhen, China. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 121, 107066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Liu, Y.; Ruan, Z.; Yang, H. Study on the optimal allocation of public service facilities from the perspective of living circle—A case study of Xiangyang High-tech Zone, China. J. Urban Manag. 2023, 12, 344–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, S.; Alahmadi, M.; Abulibdeh, A. Spatial assessment of audience accessibility to historical monuments and museums in Qatar during the 2022 FIFA World Cup. Transp. Policy 2022, 127, 116–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.; Wu, J.; Moen, W.; Hong, L. Assessing the spatial accessibility and spatial equity of public libraries’ physical locations. Libr. Inf. Sci. Res. 2021, 43, 101089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, N. Analyzing the South-North Gap in the High-Quality Development of China’s Urbanization. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Chen, J.; Xu, K. Spatial Distribution and Territorial Justice of Public Service for Disadvantaged Groups: Evidence from China. Soc. Indic. Res. 2024, 172, 741–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Yang, L.; Wu, J.; Wu, J.; Wang, G.; Bian, J.; Zeng, J.; Liu, Z. Spatio-temporal characteristics and influencing factors of traditional villages in the Yangtze River Basin: A Geodetector model. Herit. Sci. 2023, 11, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, C.; Gan, L.; Zhuo, H. Coupling Mechanisms and Development Patterns of Revitalizing Intangible Cultural Heritage by Integrating Cultural Tourism: The Case of Hunan Province, China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; He, S.; Zhang, M.; Cai, Y. Resident demand-oriented selection and spatial layout strategy for public sports facilities. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. Munic. Eng. 2024, 177, 130–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Zhang, X.; Dai, Z.; Hermaputi, R.L.; Hua, C.; Li, Y. Spatial Layout and Coupling of Urban Cultural Relics: Analyzing Historical Sites and Commercial Facilities in District III of Shaoxing. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyimu, M.; Abulikemu, Z.; Abudurexiti, A. Quantitative Evaluation of the Equity of Public Service Facility Layout in Urumqi City for Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C. Discussion on the Optimization Method of Public Service Facility Layout from the Perspective of Spatial Equity: A Study Based on the Central City of Shanghai. Land 2023, 12, 1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, A.; Liang, X.; Wen, X.; Yun, X.; Ren, L.; Yun, Y. GIS-Based Analysis of the Spatial Distribution and Influencing Factors of Traditional Villages in Hebei Province, China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Zhao, Y.; Yuan, W.; Jia, X. GIS-Based Analysis of the Regional Typology of Neolithic Archaeological Cultures in the Taihu Lake Region of China. Land 2024, 13, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Jiang, W.; He, L. Spatial distribution characteristics and influencing factors of star-level rural tourism areas in Jiangsu Province. Chin. J. Eco-Agric. 2021, 29, 366–378. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, J.; Lu, Y.; Han, F.; Ma, X.; Yang, Z. Spatial Distribution Characteristics of the Rural Tourism Villages in the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau and Its Influencing Factors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, Q.; Hu, S. Intangible Cultural Heritage in the Yellow River Basin: Its Spatial-Temporal Distribution Characteristics and Differentiation Causes. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Yue, W.; Wei, F.; Yang, G.; Chen, Y.; Pan, K. Inequality of public facilities between urban and rural areas and its driving factors in ten cities of China. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 13244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, P.; Zong, C. Research on the relationship between population distribution pattern and urban industrial facility agglomeration in China. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 16225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, X. Research on multidimensional impact assessment model of public cultural service facilities in Henan Province rural. Appl. Math. Nonlinear Sci. 2024, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Fu, M.; Hu, Q. The Behavioral Pattern of Chinese Public Cultural Participation in Museums. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Liu, S.; Ding, X. Exploring the spatial distribution pattern and influencing factors of Shanghai’s cultural functional elements based on the point of interest data. Open House Int. 2023, 48, 504–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Xu, S.; Wan, D.; Liu, H.; Zhao, L.; Guo, L.; Ren, J. Equalization Measurement and Optimization of the Public Cultural Facilities Distribution in Tianjin Central Area. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, D.; Chen, Z.; Ai, S.; Zhou, J.; Lu, L.; Yang, T. The Spatial Distribution and Influencing Factors of Urban Cultural and Entertainment Facilities in Beijing. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Liu, J.; Luo, A.; Wang, Y.; Xu, S.; Ren, F.; Su, F. Spatial Mismatch between the Supply and Demand of Urban Leisure Services with Multisource Open Data. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2020, 9, 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y. Spatial Distribution and Influencing Factors of Public Cultural Service Facilities in Inner Mongolia. Front. Econ. Cult. 2024, 2, 11–14. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, K.; Cao, X.; Wu, F.; Chen, C. Spatial Pattern and Drivers of China’s Public Cultural Facilities between 2012 and 2020 Based on POI and Statistical Data. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2023, 12, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, Y.; Liu, Y.; Cai, E.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y. Quantifying the spatiality of urban leisure venues in Wuhan, Central China—GIS-based spatial pattern metrics. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 40, 638–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Cui, C.; Liu, F.; Wu, Q.; Run, Y.; Han, Z. Multidimensional Urban Vitality on Streets: Spatial Patterns and Influence Factor Identification Using Multisource Urban Data. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2022, 11, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L.; Wu, Y.; Chu, J. Applying Spatial Techniques in Understanding Evolution and Accessibility of Cultural Facilities based on Multi-Source Data: A Case Study in Xiamen, China. J. Eng. Res. 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Yu, D.; Miao, C.; Li, G.; Feng, Y.; Bie, Q. The Location Distribution Characteristics and Influencing Factors of Cultural Facilities in Zhengzhou Based on POI Data. Sci. Geogr. Sin. 2018, 38, 1525–1534. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu, Y.-H.; Lee, M.-S.; Wang, J.-W. Culture-led urban regeneration strategy: An evaluation of the management strategies and performance of urban regeneration stations in Taipei City. Habitat Int. 2019, 86, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarei, H.; Yazdifar, H.; Ghaleno, M.D.; Namazi, N. National culture and public-sector budgeting: The mediating role of country-level institutions using a structural equation modeling approach. J. Appl. Account. Res. 2021, 23, 686–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goussios, D.; Faraslis, I. Integrated Remote Sensing and 3D GIS Methodology to Strengthen Public Participation and Identify Cultural Resources. Land 2022, 11, 1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type of Public Cultural Facility | NNI | Z Score | Confidence Level (p Value) | Spatial Distribution Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 0.087 | −33.363 | 0.000 | significant agglomeration |

| Museum | 0.523 | −10.648 | 0.000 | significant agglomeration |

| Cultural center | 0.653 | −7.209 | 0.000 | significant agglomeration |

| Library | 0.684 | −6.363 | 0.000 | significant agglomeration |

| Prefecture/City | Number of Facilities | Area (10,000 km2) | Geographical Density (units/10,000 km2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Urumqi City | 40 | 1.38 | 28.986 |

| Turpan City | 13 | 6.98 | 1.862 |

| Hami City | 15 | 14.21 | 1.056 |

| Kizilsu Kirgiz Autonomous Prefecture | 13 | 7.20 | 1.806 |

| Tacheng Prefecture | 26 | 10.50 | 2.476 |

| Karamay City | 15 | 0.73 | 20.548 |

| Changji Hui Autonomous Prefecture | 31 | 7.35 | 4.218 |

| Altay Prefecture | 24 | 11.80 | 2.034 |

| Bayingolin Mongolian Autonomous Prefecture | 34 | 47.15 | 0.721 |

| Kashgar Prefecture | 45 | 16.20 | 2.778 |

| Ili Kazakh Autonomous Prefecture | 37 | 5.65 | 6.549 |

| Hotan Prefecture | 24 | 24.81 | 0.967 |

| Bortala Mongol Autonomous Prefecture | 18 | 2.72 | 6.618 |

| Aksu Prefecture | 30 | 13.25 | 2.264 |

| Total/Average Density | 365 | 169.98 | 2.147 |

| Classification Dimension | Geographical Density Range (units/10,000 km2) | Per-Capita Quantity Range (units/10,000 people) | Prefecture/City |

|---|---|---|---|

| high density—high per capita | (2.147–28.986] | (0.149–0.369] | Karamay City, Changji Hui Autonomous Prefecture, Tacheng Prefecture, Bortala Mongol Autonomous Prefecture |

| low density—high per capita | (0.721–2.147] | (0.149–0.369] | Turpan City, Hami City, Bayingolin Mongolian Autonomous Prefecture, Kizilsu Kirgiz Autonomous Prefecture, Altay Prefecture |

| high density—low per capita | (2.147–28.986] | (0.096–0.149] | Urumqi City, Aksu Prefecture, Kashgar Prefecture, Ili Kazakh Autonomous Prefecture |

| low density—low per capita | (0.721–2.147] | (0.096–0.149] | Hotan Prefecture |

| Detection Factor | Specific Indicator | Factor | Variable Explanation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Population Size | Annual Population Number | X1 | Regional population scale |

| Economic Level | GDP | X2 | Regional economic scale |

| Cultural Demand | Baidu Index | X3 | Annual average Baidu index of “culture” |

| Fiscal Capacity | Public Budget Expenditure | X4 | Regional public budget expenditure scale |

| Education Level | University Enrollment | X5 | Number of university students |

| Transportation Conditions | Road Network Density | X6 | Road length per km2 |

| Detection Factor | Overall | Museum | Cultural Center | Library |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population Size | 0.806 | 0.746 | 0.820 | 0.774 |

| Economic Level | 0.743 | 0.881 | 0.583 | 0.583 |

| Cultural Demand | 0.777 | 0.698 | 0.687 | 0.752 |

| Fiscal Capacity | 0.607 | 0.496 | 0.620 | 0.764 |

| Education Level | 0.594 | 0.371 | 0.639 | 0.792 |

| Transportation Conditions | 0.360 | 0.293 | 0.396 | 0.312 |

| Detection Factor | X1 | X2 | X3 | X4 | X5 | X6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X1 | 0.806 | |||||

| X2 | 0.937 | 0.743 | ||||

| X3 | 0.943 | 0.814 | 0.777 | |||

| X4 | 0.871 | 0.886 | 0.890 | 0.607 | ||

| X5 | 0.878 | 0.877 | 0.875 | 0.620 | 0.594 | |

| X6 | 0.946 | 0.816 | 0.909 | 0.977 | 0.832 | 0.360 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, X.; Hou, J. Spatial Differentiation Characteristics and Influencing Factors of Public Cultural Facilities in Xinjiang. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4994. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17114994

Li X, Hou J. Spatial Differentiation Characteristics and Influencing Factors of Public Cultural Facilities in Xinjiang. Sustainability. 2025; 17(11):4994. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17114994

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Xiao, and Jiannan Hou. 2025. "Spatial Differentiation Characteristics and Influencing Factors of Public Cultural Facilities in Xinjiang" Sustainability 17, no. 11: 4994. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17114994

APA StyleLi, X., & Hou, J. (2025). Spatial Differentiation Characteristics and Influencing Factors of Public Cultural Facilities in Xinjiang. Sustainability, 17(11), 4994. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17114994