Abstract

Integrated Reporting (IR) has gained prominence as a comprehensive approach to corporate disclosure, yet theoretical clarity is still developing regarding how governance mechanisms shape IR quality and its relation to ESG risk ratings. Addressing this gap, this study explores the influence of board and audit committee characteristics on IR quality and whether an improved IR quality is associated with a lower ESG risk. Drawing on different theories, this research examines how governance structures enhance transparency and accountability in line with societal expectations. Based on panel data from 158 firms across four years (2019–2022), a random effects Panel EGLS regression model is employed along with an endogeneity check. Findings show that board independence and the presence of women members significantly enhance the IR quality, while board size is not a determining factor. Similarly, audit committee independence and meeting frequency positively influence the IR quality, whereas committee size does not. Furthermore, firms with a higher IR quality demonstrate significantly lower ESG risk scores. These results underscore the theoretical proposition that effective governance improves disclosure credibility and reduces information asymmetry. This study suggests that reinforcing board independence and diversity can enhance reporting quality and stakeholder trust, offering a strategic path toward more sustainable and transparent corporate behavior.

1. Introduction

A high information quality is undoubtedly demanded by most stakeholders. Accordingly, improving information quality is a vital objective of reporting entities in both their financial and non-financial reporting practices. The International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRSs) and Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) leads the way in improving the quality of information in financial reporting as well as sustainability and environmental, social, and governance (ESG) reporting. Therefore, the consideration of the IR framework provided by the International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC) is expected to be a contributing factor to the Integrated Reporting (IR) quality. However, findings in the recent literature indicate that the IR quality is still low [1,2] or under development [3]. While the adoption of a set of standards or frameworks is thought to be one of the most effective ways to contribute to the quality of information and reporting, there may be other key determinants of quality.

In addition to delivering high quality content by adapting standards and frameworks, reporting quality can also be seen as a solution to mitigate the negative effects of information asymmetry. According to agency theory, in financial reporting practice, information quality stands out as the most vital factor that should be met to alleviate the negative effects of asymmetric information [4,5] and to improve firm performance [6]. The literature also suggests that one of the main roles of financial and non-financial reporting practices is to mitigate the negative impact of information asymmetry and agency costs [7,8]. Therefore, information asymmetry can be reduced through the faithful presentation of corporate reports. In this context, according to the OECD’s principles of corporate governance [9], corporate governance mechanisms are an integral part of businesses in order to overcome information asymmetry and ensure timely disclosures. Corporate governance mechanisms consist of key components which are the board of directors, ownership structures, executive compensation, internal control and risk management, transparency and disclosure, shareholders’ rights and engagement, and legal and regulatory frameworks [10,11]. Considering the internal mechanisms of corporate governance, the board of directors, executive management, and independent control are of great significance [12]. In this context, by disclosing key financial and non-financial information [8,13,14], the board is expected to mitigate the negative effects of the agency problem arising from information asymmetry [10,15]. Additionally, in regard to independent control mechanisms [12], the audit committee has a vital role in monitoring activities and assuring the information reported to the relevant bodies of the organization. Accordingly, the audit committee contributes to improving the quality of information [16,17]. Consequently, the role of the board of directors and audit committee in improving the information and reporting quality should not be underestimated. Given the agency theory, which emphasizes the significant role of the board of directors and independent control mechanisms in improving reporting quality for organizational excellence [8,10,15], this relationship can be extended to the IR quality. Therefore, different characteristics of the board of directors and audit committee, such as its size, independence, and number of women and meetings, are expected to be factors to cope with information asymmetry and improve transparency and accountability, which in turn may positively affect the IR quality.

Not only financial performance but also non-financial performance is the main interest of IR, where IR provides the link between these issues. The effective implementation of ESG approaches requires strong accounting practices that promote transparency and accountability in corporate reporting, along with sustainability accounting to demonstrate how corporate activities align with ESG objectives [18,19]. ESG reporting is therefore built on sustainable development [20,21]. Accordingly, IR stands out as a promising solution to ensure that corporations report correct information about their sustainability activities [22] along with integrated financial information [23]. ESG reports provide summary information to target audiences regarding metric or historical performances related to the ESG approach of the firm. IR surpasses historical performances by focusing on long-term value creation, but also incorporates ESG practices into the normal business cycle. Accordingly, this reflection of ESG in IR focuses on the firm’s stakeholders, who are anyone with an interest in the company, such as customers, employees, environmental interest groups, or regulatory authorities, rather than only shareholders [24]. Firms seeking to attract investors for their financial assets while ensuring strong corporate governance structures and environmentally friendly approaches have also started to receive ratings for their ESG practices [25,26]. Given that the link between the sustainability approaches of the firms might be reflected in the ESG scores, IR quality should also be believed to reduce firms’ ESG risks [27]. Therefore, there might be a relationship between the ESG risk rating and IR quality because an IR approach is expected to lead to improved transparency and accountability.

Focusing on the interlinked relationship between the role of the board of directors, audit committee, IR quality, and ESG risk rating, this paper focuses on two main research questions:

RQ1. What is the effect of the board of directors and audit committee on IR quality?

RQ2. Is a higher IR quality associated with lower ESG risk ratings?

In recent years, the number of studies focusing on IR has been increasing in the literature, but according to Dumay et al. [28], there is a lack of studies addressing the implementation of IR. Accordingly, the literature is mainly focused on different pillars of the IR framework and IR quality criteria [1,2,29,30]. Additionally, to address the determinants of quality, the impact of the board of directors on IR is analyzed by a few studies. However, in those studies, both positive [30] and mixed results [2] are reported. In other words, no definite conclusion has yet been reached. Furthermore, these studies utilized different methods and pillars of the IR framework in order to measure IR quality, rather than fully adopting the framework to propose a consistent measurement method. Therefore, there is still a lack of consistency in the literature on the measurement of IR quality [31]. Moreover, previous studies on IR quality and its different determinants have mostly used one-year [30,32,33,34] or two-year data [1,3] to estimate results with low sample sizes. To the best of our knowledge, studies on the relationship between the ESG performance and IR quality are limited to Mans-Kemp and Van der Lugt [35] and Appiagyei and Donkor [36]. However, these studies only emphasized the South African perspective and offered no conclusions on ESG risk ratings and complete IR quality measurements.

Considering the background provided, this study is grounded on measuring IR quality by offering a complete scoring method on the basis of a 4-year period to obtain consistent results. Moreover, this paper investigates whether the board of directors and audit committee characteristics have an impact on IR quality, and it seeks to understand if the IR quality is reflected in lower ESG risk ratings. With respect to these gaps, the contribution of this study to the literature consists of four stages. First, unlike the recent studies [1,2,3], this paper fills the gaps in the measurement of IR quality considering “Guiding Principles”, “Content Elements”, and “Fundamental Concepts” together. In this regard, this paper reflects the three major pillars of the IR framework and develops a consistent scoring method to measure the IR quality properly, which brings novelty to the literature. Secondly, this paper investigates if there are sectoral effects in the adoption of the IR framework that lead to a different IR quality. Then, the role of the IR quality in ESG risk rating reductions is explained in relation to enhanced transparency and accountability through the role of the board of directors and audit committee. Finally, the results of this study are believed to be more consistent and reliable as they are based on a panel data analysis for 4-year periods and are combined with a further data analysis as an endogeneity check.

This paper examines the integrated reports of 158 firms with a 632-firm observation between 2019 and 2022, when high-volumes of IR are available. Regarding previous years, it is not possible to reach a high volume of integrated reports due to the newness of the IR framework. Moreover, the choice of this timeframe is critical to highlight the post-COVID-19 situation regarding the unexpected impact on both the financial and non-financial activities of firms. To obtain results, a Panel Estimated Generalized Least Squares (Panel EGLS) analysis is conducted, where an endogeneity check is performed through a system generalized method of moments (GMM). The results of this study are expected to provide a comprehensive understanding of the subject. It points out that board independence and the proportion of women on boards, as well as audit committee independence and meeting frequency, are positively associated with the quality of IR, while the board and audit committee size reveal insignificant effects. Additionally, higher IR quality is linked to lower ESG risk ratings, emphasizing the role of transparent and comprehensive reporting in improving corporate ESG responsibilities. Theoretically, this paper contributes to the literature by positioning IR quality as both a reflection of effective corporate governance and a driver of reduced ESG risk, which is reflected by ESG risk ratings. In this regard, an improved IR quality is possible through enhanced transparency and accountability, which expands mainly agency, legitimacy, and stakeholder theories. Consequently, this study is of great importance for IR practitioners, corporate governance structures, policy makers, and stakeholders and investors interested in ESG performance. This study proceeds with its literature review, theoretical background and hypothesis development, research methodology, empirical results, and conclusion and discussion.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Integrated Reporting

The primary purpose of IR is to create a link between the key information of reporting entities on the overall activities of a company that drive value creation [23,37,38]. Accordingly, IR provides meaningful explanations on financial information, strategies, governance, sustainability, business models, capitals, business outlooks, risks, opportunities, and performance [27,39]. Under the changing conditions of today’s business environment, IR is one of the most proper reporting practices that can provide meaningful, effective, and efficient information to various stakeholders. IR practices enable communication about both positive and negative aspects of businesses [23,37]. Therefore, the most important role of IR should be to contribute to improving the quality of information [23,39,40], resulting in reducing information asymmetry [29]. To summarize, IR extends beyond the financial and non-financial reporting practice, which reflects a better picture of the reporting entities together with high information quality. Therefore, meeting quality expectations in IR practices is essential, and this study will contribute to this matter.

2.2. Quality in Corporate Reporting Practices: Integrated Reporting Quality

The previous literature has shown that IFRS adoption is one of the factors contributing to the quality of financial reporting practices [41]. In terms of sustainability reporting, evidence also suggests that the framework set by the GRI is crucial for reporting quality [42,43]. Apparently, the set of principles, standards, and frameworks plays a vital role in improving the reporting quality. The powerful content of IR is believed to increase transparency and accountability, which contribute to building trust between users of information and reporting entities [23,29]. Therefore, IR quality enables better decision making and positively impacts cost management and cash flow [44]. Moreover, IR quality improves forecast quality and reduces the cost of equity [40]. In other words, essential information should be provided in a clear, understandable, and concise manner, providing numerous benefits for both business and each information user. For this reason, a high quality is expected by both internal and external users of information. Accordingly, a certain level of quality should be ensured in reporting practices. The IR framework prepared by the IIRC is believed to be an important guide to meet high-quality criteria and standards in IR practices.

Considering the content and features provided by IR, reporting entities should be expected to meet a high IR quality for many reasons. Given the role of the IFRSs and GRI in improving quality, it is believed that a framework or standard would also enhance the quality of IR practices. In 2013, the IIRC published the internationally recognized IR framework, which is now part of the IFRSs. The main objective of the IR framework is to improve the quality of information and contribute to the process of communication, accountability, transparency, and value creation [23]. Therefore, the degree to which reporting entities adopt the IR framework is closely related to IR quality [2]. This can foster a transparent, accountable, and sustainable business environment, as desired by financial capital providers and other stakeholders.

The IR framework has also been extensively reviewed by the recent literature focusing on IR quality [1,2,3,30,32,45]. Some of these studies have attempted to demonstrate the importance of IR quality by considering the IR framework, while others are focused on identifying other factors that contribute to IR quality. However, instead of addressing the IR framework holistically, these studies point to different pillars as important factors for assessing IR quality. In some of the studies, the need for a new measurement method is even stated as a limitation [2,30]. Therefore, there is a gap in the literature in terms of measuring IR quality [31]. According to the IIRC [23], the main aim of IR is to consider the IR framework and to apply its “Guiding Principles” and “Content Elements” and to explain “Fundamental Concepts” that underpin them. Therefore, it is expected to consider the IR framework in its entirety to measure IR quality. In this respect, the aim of this paper is to contribute to the literature.

2.3. The Relationship Between Corporate Governance and IR Quality

The existing literature shows that the implementation of the IR framework is critical to improve IR quality. However, several other factors are also believed to have an impact on IR quality, such as national culture [32], profitability, firm size, financial leverage [33], and the stakeholders’ pressures [45]. It is also noted that the quality of IR is affected by the board, but both positive [30] and mixed results [2] are shown. Accordingly, complex results on the characteristics of boards of directors are reported. In addition, IR is more than just a reporting exercise aimed at getting companies to think in an integrated top-down way. This suggests that IR has a positive impact on the way companies are managed [39]. Velte and Stawinoga [46] stated that IR and corporate governance should be considered together through integrated thinking.

Corporate governance is defined as how corporations are managed and controlled under different mechanisms in connection with various stakeholders [47,48]. The OECD [9] (p. 37) explains that “the corporate governance framework should ensure that timely and accurate disclosure is made on all material matters regarding the corporation, including the financial situation, performance, ownership, and governance of the company”. Stated otherwise, corporate reporting practices, which are an important part of corporate governance, fulfill the role of communicating with stakeholders on business-related issues. Corporate governance consists of two main mechanisms, which are internal and external [49,50]. The findings show that the internal mechanisms of corporate governance enhance the quality of financial information [51,52]. There is also evidence that corporate governance mechanisms serve to ensure the quality of voluntary reporting practices [12,53], such as sustainability reporting [54] and environmental reporting [55]. Most of these studies focus on different features of the internal mechanisms of corporate governance, such as board independence, audit committees, board size, gender diversity, and CEO duality [2,30,50,51,56,57,58]. Given these characteristics, the board is believed to have the most important role [12], and their role is to assure information quality to handle information asymmetry [30]. Furthermore, as part of the internal mechanisms, internal audits or audit committees play a critical role [12]. As noted by Cohen [59], the audit committee has a key role to perform in improving reporting quality. There are a limited number of studies in the literature that focus on a specific country rather than providing a comprehensive result from different perspectives [58]. Taken together, a positive relationship is expected between IR quality and the internal mechanisms of corporate governance, including the board of directors and the audit committee. However, a limited number of studies have shown both positive and mixed results, ignoring the full evaluation of the IR framework to provide reliable measurements. Correspondingly, introducing a consistent IR scoring model as well as empirically testing the effects of the board of directors and audit committee is one of the main motivations behind this study.

2.4. IR Quality and ESG Ratings

Considering environmental and social issues and problems, transparency and accountability are key concerns for most firms [60], in which these issues and problems are part of voluntary reports. As it has been indicated before, the IR framework is centered three major pillars, which are Fundamental Concepts, Guiding Principles, and Content Elements. The nature of the IR framework also consists of information regarding economic, social, and governance perspectives, especially in terms of the six capitals. According to the IIRC [23], the six capitals are related to financial, human, social, intellectual, manufacture, and natural capitals. In fact, some of these capitals are relevant to ESG indicators. Therefore, a relationship can be expected between the ESG approaches of firms and IR quality. However, considering the recent literature, ESG aspects are mostly addressed from the perspective of financial performance [61,62,63] and sustainability reporting [23,64]. In these studies, the ESG score is widely used to determine the ESG performance of firms. Although IR is believed to be one of the most appropriate approaches to explain firms’ ESG practices [22,65], the number of studies on this subject is limited. Considering some of these studies, Conway [66] analyzed the relationship between sample IR-recognized firms and ESG ratings over six years. The results showed that IR has no significant impact on ESG ratings and vice versa. The study also emphasized that the whole governance performance is an indicator of the IR quality, while the social and governance pillars do not serve as factors in the IR quality. Churet and Eccless [27] found weak evidence considering the relationship between ESG scores and IR, especially in the healthcare sector. Conway [24] investigated South African companies and observed a decline in financial performance after the implementation of mandatory reporting, followed by an increase in institutional shareholding. Moreover, higher quality reports are linked to a lower financial performance but better ESG scores. Accordingly, it is indicated that the ESG rating is associated with financial reporting quality [67]. Moreover, IR quality is addressed in relation to the sustainability and financial performance of firms in South Africa by Mans-Kemp and Van der Lugt [35]. However, while this study measures IR quality without using quantitative measures, it also focuses only on South African firms where IR is mandatory. The relationship between IR quality and sustainability performances is also tested by Appiagyei and Donkor [36] by considering South African firms. However, this study excludes issues related to the holistic measurement of the IRQ depending on the framework and ESG risk level, taking into account narrow perspectives in South Africa. Accordingly, in these studies, different scoring methodologies are considered rather than using the three pillars of the IR framework and ESG risk metrics. The fact that companies’ ESG ratings are considered by investors in their decision-making processes is an indication of the growing interest in companies’ ESG scores and performance [26,68]. Therefore, a number of organizations score their ESG performance. Among the various rating agencies, Sustainalytics’ ESG risk score differs from others in terms of the measurement of the ESG risk level in different ranges. Moreover, Sustainalytics’ ESG risk score has a clear rating methodology that provides information on ESG risk as well as financial risk [69]. This metric consists of different ranges, in which 0–10 is negligible, 10–20 is low, 20–30 is medium, 30–40 is high, and 40+ represents severe risk. Considering all the provided background together, the use of the ESG risk metric and IR quality measured through the framework is believed to bring novelty to the literature. Therefore, in light of the importance of ESG risk ratings, and in consideration of the ESG components of the IR Framework and IR quality, a significant and negative relationship between the ESG risk rating and IR quality is expected.

3. Theoretical Background and Hypothesis Development

To draw a conclusion, the role of the board of directors and audit committee on IR quality and ESG risk ratings are the most prominent components of this study. Accordingly, the corporate governance structure, as one of the main components of this study, is mostly explained by the agency theory [10,11,70]. In terms of agency theory, the idea of the separation of ownership and control leads to the creation of three main costs, which are monitoring, bonding, and residual loss [11]. In this context, given their roles, agents may have more information power than other stakeholders. Under this condition, agents can use this information for their own benefits or against the interest of shareholders. It is a circumstance that results in information asymmetry and agency problems, respectively [71]. A well-structured relationship between agents, shareholders, and other stakeholders is necessary to deal with this problem. According to Goergen [72], corporate governance is recognized as the most appropriate way to handle the unintended consequences of the agency problem. As part of the internal mechanisms of corporate governance, the role of the board in aligning the interests of agents and shareholders to eliminate the agency problem should not be underestimated [8,10,15]. The relationship between agents and shareholders, in which the board has a critical role, is regulated through the provision of financial [8,73] and non-financial information [13]. Moreover, as a major part of the internal mechanisms, the audit committee plays a key role, leading to the increased relevance and quality of information in financial and non-financial reporting practices [74,75]. Agency theory also emphasizes the significance of transparency and accountability, which are ensured by reporting practices [76]. Therefore, financial and non-financial reporting practices are believed to play an important role in mitigating the negative impact of information asymmetry and agency problems. In other words, it is essential to present financial and non-financial information faithfully and to ensure a high quality in these reports. In this context, the need for financial and non-financial reporting has emerged mainly as a result of information asymmetry and agency problems [4,7,8]. Considering the agency theory, it is believed that among the different mechanisms of corporate governance, the board of directors and the audit committee play quite prominent roles. This is recognized as the point where corporate governance and IR converge in the theoretical perspective, and it is thought that the quality of the IR can be enhanced by the role undertaken by the board of directors and the audit committee. Consequently, the role of the board and audit committee in IR implementation will improve the quality of the content and information provided, thus overcoming the problems of information asymmetry and agency.

While agency theory is expected to be the most appropriate way to explain the relationship between corporate governance mechanisms and the importance of quality in reporting practices, there are other theories that accompany this relationship. Accordingly, legitimacy theory suggests that a bridge should be built between stakeholders and the organization based on informing both parties through corporate reporting practices [77]. Moreover, the signaling theory put forward that precise and reliable information should be signaled by reporting entities for the users of information, which is critical for reducing the negative effect of information asymmetry [78]. In light of these theories, it is clear that the role of providing financial and non-financial information is fulfilled by reporting practices. Therefore, considering today’s information needs, in which improving quality is of great significance, this role can be fulfilled by the IR practice. Moreover, considering the stakeholder theory [79], voluntary information aims to meet the interest of stakeholders, where the disclosure of additional information about the non-financial activities of firms is a significant indicator of accountability. In light of these various theories, improving IR quality through the influence of the board of directors and the audit committee also allows firms to improve their transparency and accountability by disclosing interconnected information. For this reason, concerns about transparency and accountability put more pressure on firms to provide more information about their ESG activities, which may in turn lead them to put ESG issues on their agenda and reduce ESG risks which are reflected in their ratings.

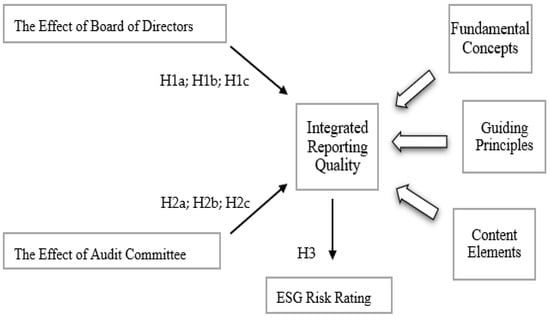

The mandatory and voluntary reporting approaches are main drivers of corporations to inform main users of reports for many reasons. According to Frank [80], frameworks, principles, or standards that are issued by the IFRSs and GRI are the leading force to deal with complexity in reporting practices. Also, in the view of the mentioned literature, the IR framework is indicated as a factor to improve IR quality. However, the quality of voluntary reporting practices can also be effectively enhanced through corporate governance mechanisms [12]. IR improves its popularity as a new voluntary reporting tool. Accordingly, in order to show a holistic picture of a business and its value creation story in an advanced way, the IR quality should be improved by reporting entities [81]. To summarize, a positive relationship is expected between the internal mechanisms of corporate governance and IR quality considering the role of the board of directors and audit committee. In this respect, the improved transparency and accountability through the role of the board of directors and audit committee is believed to be an indicator of increasing IR quality. Also, ESG performances, which are an important part of IR practice, attract the attention of information users, in which the improved IR quality may therefore result in lowering the ESG risk rating. To answer each research question, the following theoretical framework in Figure 1 and seven hypotheses are proposed as follows.

Figure 1.

Theoretical framework.

3.1. The Effect of the Board of Directors on IR Quality

Within corporate governance regimes, the board of directors has non-identical characteristics concerning its independence, size, gender, and monitoring activities, which may vary from one corporation to another. Fama and Jensen [10] stated that at the board level, a distinction is expected between decision management and decision control, which contribute to information quality. Therefore, to improve information quality, directors’ actions should be controlled by independent members or non-directors. The evidence in the literature also supports this idea regarding the positive relationship between the quality of voluntary reporting practices, the level of information, and the number of independent board members [82]. Within the agency theory, board independence is crucial for monitoring management and reducing agency costs. Independent directors are less likely to align with managerial interests and are more likely to demand transparent, high-quality reporting [70]. In this context, the effectiveness of corporate governance may depend on the existence of independent board members [10,57,83,84]. Consequently, the number of independent members on the board of directors is believed to be a factor that improves the IR quality. Therefore, H1a is stated as follows:

H1a.

There is a significant and positive relationship between board independence and IR quality.

IR is grounded in integrated thinking, and it consists of different types of information on both financial and non-financial business activities of firms. According to Frias-Aceituno et al. [75], the board of directors is made up of a diverse number of members, which means that at the board level there are a variety of members with different experiences, skills, backgrounds, and levels of education. Given the qualitative characteristics of different board members, they are expected to contribute to information quality. The relationship between the board size and IR quality is debated from the theoretical perspective. While larger boards may offer diverse expertise (e.g., legitimacy theory), they may also suffer from coordination issues. In this context, the positive relationship between the board size and information quality are examined in different studies [57,85,86]. Although no ideal board size has yet to be determined, it is believed that there can be a positive relationship between the number of board members and IR quality. Therefore, H1b is proposed as follows:

H1b.

There is a significant and positive relationship between the board size and IR quality.

The preceding paragraphs reveal that the number of independent members and the size of the board of directors is believed to impact IR quality. Under these circumstances, board diversity is also expected. In this regard, board diversity is anticipated by considering social and cultural differences between board members [84]. Accordingly, women board members can be more skilled in problem solving, the effective use of communication skills, and participation in various business activities. Rovers [87] stated that corporations perform better when woman are involved as a part of the board of directors. In addition, board diversity enables the emergence of new and various ideas, in which women can contribute to the decision-making process positively [88]. From the stakeholder and legitimacy theory perspectives, gender-diverse boards are more likely to promote inclusive and transparent communication, enhancing the quality of IR [77,79]. Therefore, it is thought that women can pay more attention to social, environmental, and governance issues, which may lead to an increase in the quality of information in reporting practices. So, information quality in reporting practices can be explained through the role of woman, which can increase the importance of the number of women on the board of directors [57,89,90]. The proportion of women on boards is expected to contribute positively to IR quality, where H1c is proposed as follows:

H1c.

There is a significant and positive relationship between the percentage of women in the board of directors and IR quality.

3.2. The Effect of the Audit Committee on IR Quality

There are numerous business activities that need to be monitored and reported to the board. Therefore, the audit committee plays an important role in the corporate governance regime and is expected to be a contributing factor to the quality of IR. Maassen [91] identified that the audit committee fulfills two important roles, monitoring financial activities and reporting important information to the board of directors. Accordingly, the audit committee helps to deal with information asymmetry [92], which enables the improvement of information quality [16]. Consistent with agency theory, independent audit committees serve as effective monitors of financial and non-financial disclosures [70]. The role of the audit committee under the corporate governance mechanisms is believed to contribute to the IR quality accordingly. Therefore, it can be stated that the number of independent members in the audit committee can be a determining factor of IR quality [58,81,93]. Although the audit committee is expected to be fully independent, due to the influence of the culture and ownership structure of companies, permanent members of the board of directors are also included in the audit committee. In short, H2a suggests that there may be a positive relationship between the number of independent members on the audit committee and IR quality.

H2a.

There is a significant and positive relationship between audit committee independence and IR quality.

As stated in H1a, the board size is a critical determinant of the qualitative characteristics of board members. Correspondingly, the size of the audit committee can be considered as an important factor that positively impact reporting quality [18,58,94]. The size of the audit committee may influence effectiveness through resource availability but may also lead to inefficiencies. Empirical studies are inconclusive, with some suggesting no significant impact on IR quality [2]. Therefore, a larger audit committee size can be positively associated with IR quality, and H2b is proposed as follows:

H2b.

There is a significant and positive relationship between the size of the audit committee and IR quality.

The number of meetings of the audit committee can also be regarded as another vital determinant of corporate governance [58,95]. Increasing the number of meetings held can be another important indicator in terms of presenting and discussing different ideas, which is expected to increase the quality of IR. More frequent audit committee meetings may indicate stronger oversight and a proactive approach to disclosure quality, which is consistent with agency theory [70]. Studies have shown that active audit committees are associated with a better reporting quality. In this regard, the hypothesis H2c is formulated as follows:

H2c.

There is a significant and positive relationship between the number of meetings of the audit committee and IR quality.

3.3. The Effect of IR Quality on ESG Risk Ratings

Although IR is more focused on a firm’s capital providers and stakeholders, ESG reports only aim to fulfill stakeholders’ demands for non-financial information. However, there is still an important link between both types of reporting. As highlighted by the IIRC [23], integrated reports offer information about an organization’s connections with its key stakeholders and how the firm approaches meeting their needs. According to Brooks and Oikonomou [96], the stakeholder theory and legitimacy theory are often cited as underpinning environmental, social, and governance explanations that enhance corporate legitimacy and persuade stakeholders. Therefore, it is believed that non-financial reporting practices are a way to enhance corporate legitimacy and convince stakeholders about firms’ ESG activities. Furthermore, such reports are critical to ensure the accountability of the firm as stated in the stakeholder theory [79]. Accordingly, it is expected that a higher IR quality, together with stakeholders’ pressure and information needs, may lead firms to provide more ESG-related information. Given the nature of the agency problem, ESG-related information that is presented through IR in a connected way can be seen as an alternative solution to information asymmetry. Moreover, this information, which also reflects the general outlook of the business, is believed to be critical for ESG rating agencies. So, a high IR quality is more likely to lead to the provision of detailed information on a firm’s environmental, social, and governance approaches. In addition, from a legitimacy and stakeholder theory lens, better IR quality enhances transparency regarding ESG performances, which may reduce the perceived ESG risk. Firms with higher-quality IR are better positioned to address stakeholder concerns and sustainability risks. Therefore, it is expected to push firms to improve their ESG performance and to report on their positive work, which in turn may result in lowering the ESG risk rating.

H3.

There is a significant and negative relationship between IR quality and ESG risk ratings.

4. Research Methodology

4.1. Sample Size and Data Collection

The sample size of this study consists of 158 firms that published integrated reports and received a Sustainalytics’ ESG risk rating between 2019 and 2022 regarding the different industries. Firms that implement the IR framework in their IR practices are listed on the IIRC’s website under the reporters’ section. For this reason, firms that are listed on the website of the IIRC (IFRS Foundation) are expected to be the best examples in compliance with the IR framework. In addition, on this website, 496 firms are identified as the IR preparer. However, it was observed that various reports were published by these listed firms under different names, such as the Integrated Sustainability Report, Impact Report, Annual Report, Integrated Annual Report, and so on. Even though these reports were listed on the website of the IIRC, the reports that were only named as integrated report and Integrated Annual Report were selected as the sample size to increase consistency. Moreover, it was noticed that due to the newness of the IR framework, a low number of Integrated Reports were published in the previous years. Among the different years, 2019 stands out for the high number of companies that started publishing IRs. In addition, it is of great importance that these firms receive a Sustainalytics’ ESG risk score. Considering these conditions, 11 main industries were observed among the IR preparers. These were financial services, the industrial sector, consumer goods, basic materials, consumer services, telecommunication, technology, healthcare, the public sector, utilities, and real estate. However, the majority of the population was observed within the financial services, industrial sectors, and consumer goods. Therefore, to obtain a sufficient number of firms from each industry, the population was divided into 11 industries. Then, the sample was randomly selected among the IR reporters, in which they had ESG risk ratings and reports named as integrated report or Integrated Annual Report. In a nutshell, the selection criteria included the following: (1) the availability of consistent IR disclosures over the 4-year period, (2) a publicly listed status to ensure the availability of financial data, and (3) an ESG risk rating coverage by Sustainalytics. Firms not meeting these criteria or with missing data were excluded from the analysis. Regarding all these circumstances, the final sample of this study reached 158 firms with 632 firm observations between 2019 and 2022. Table 1 presents the distribution of the sample size considering the different industries.

Table 1.

Distribution of the sample.

In order to answer the research questions of this study, all relevant data were accessed through the published Integrated Reports or Integrated Annual Reports. Therefore, the website of the IFRSs (https://examples.integratedreporting.org/ir-reporters/, accesed on 10 April 2024)was used to access Integrated Reports to measure the IR quality. Moreover, the nature of the integrated reports or Integrated Annual Reports allowed us access to information about the board of directors, audit committee, Sustainalytics’ ESG risk rating, and other control variables. Otherwise, this information was accessed through the corporate governance reports and the firms’ and Sustainalytics’ websites.

4.2. Model Specification

One of the main objectives of this study is to test the impact of internal mechanisms of corporate governance on the IR quality and whether IR quality is effective in reducing ESG risk ratings. On the basis of the theoretical framework that is addressed, it is believed that the board of directors and audit committee may have a significant impact on IR quality, and therefore IR quality may lower ESG risk ratings. Correspondingly, seven different hypotheses were developed depending on the two different internal mechanisms of corporate governance and the ESG risk rating. Consequently, considering the inclusion and exclusion of industry effects, three main models were proposed, in which these models were estimated by using Panel Estimated Generalized Least Squares (Panel EGLS). While 3 different independent variables are indicated as predictors of IR quality in both Model 1 and Model 2, IR quality is the dependent variable of these models as an outcome. This time, in Model 3 the IR quality is the predictor of the ESG risk, which is reflected by the ESG risk rating. In addition, the number of integrated reports published, type of integrated report as voluntary IR practice, presence of a sustainability committee, total assets, and return on assets (ROA) are control variables for each model. These models are shown in the following sections:

Model 1. The effects of the board of directors on IR quality

Model 2. The effect of the audit committee on IR quality

Model 3. The effect of IR quality on the ESG risk rating

4.3. Variables and Measurement

Considering the research questions and proposed models of this study, this paper contemplates on previous studies that considered IFRS and GRI frameworks as a means of measuring the reporting quality in both financial and non-financial reporting practices [42,97]. According to Hammond and Miles [98], background, content, assurance and reliability, and form are determined as the four main areas to meet the quality criteria. In compliance with the IR framework and these four main areas, a scoring model is offered by Pistoni et al. [1] to measure IR quality. In the different studies of Vitolla et al. [30,32,45], a scoring model that is inspired by Pistoni et al. [1] is derived to measure IR quality in the same way. Subsequently, the “Content Elements” of the IR framework are considered by Songini et al. [2] to measure the IR quality through a scoring model. The methodology for measuring the reporting quality should fully address all aspects of the standards or frameworks [99]. Therefore, the consideration of only the content area in scoring IR is issued as a limitation by Songini et al. [2], and the development of a different scoring model is proposed by Vitolla et al. [30]. In order to bring novelty to the literature, this study offers a complete scoring model that is based on 3 main areas of the IR framework. In this scoring method, a total of 18 questions are adapted from the IIRC’s IR framework to measure IR quality [23]. A Likert scale-based scoring technique is developed following the previous studies in the literature [1,2,3,30,32,34]. Furthermore, the distribution of questions, the measurement scale, and maximum scores under the relevant pillars of the IR framework are visualized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Scoring IR quality.

According to Table 2 and Table 3, 3 of these questions relate to Fundamental Concepts, 7 to the Guiding Principles, and 8 to the content’s elements. The relevant questions and scoring model used to score IR quality are also shown in Table A1 in Appendix A. Therefore, considering the 18 questions, each integrated report is scored by using a 4-point scale. This scoring model involves a range of scores between 0 and 3, where these scores represent the following: 0 = absence of information; 1 = poor information; 2 = balanced information partially supported by quantitative data; and 3 = excellent information supported by quantitative data. In order to overcome subjectivity and ensure inter-coder reliability, sampled integrated reports are scored by two coders. Cohen’s Kappa is used as a way to assess the agreement between the sample of coder 1 and coder 2 [100]. The result suggests that there is a significant agreement between the coders with a Kappa statistic of 0.71, which is suitable for further data analysis.

Table 3.

Variables.

To test proposed Models 1–3, and various variables are used by this study. Considering this scoring method, IR quality is first measured as a dependent variable in both Model 1 and Model 2 and then as an independent variable of Model 3. The variables, related measures, similar proxies, and data source used in this paper are presented in Table 3. In the literature, board independence is measured by the ratio of independent board members to the total number of board members [57,83,85]. The board size is measured by the total number of board members [38,57,85]. The number of women on the board is measured by the percentage of women in the total board size [57,75,84,90]. The number of independent members on the audit committee is a significant factor to alleviate the negative effect of information asymmetry and to improve performance [103], which is measured by the percentage of independent members on the audit committee [58,104]. In addition, having a large number of members on an audit committee can benefit IR quality through the discussion of different ideas [105]. Accordingly, the audit committee size is measured by the total number of members on the audit committee [58,104,106]. Lastly, the number of audit committee meetings is expected to be a critical factor leading to an increase in the effectiveness of monitoring activities [95], which may result in the provision of reliable and consistent information. Therefore, the number of meetings held can improve IR quality. To measure the number of audit committee meetings, the total number of meetings held is considered [58,104]. The usage of ESG scores is also popular in the literature. The main discussions in these studies include the impact of ESG scores on firm value and profitability [61], the impact of ESG scores and financial performance [62,63], and ESG disclosure scores on firm performance [101]. ESG risk scores that are measured by Sustainalytics are addressed as a dependent variable in Model 3. Sustainalytics is an independent firm that measures the ESG risk of firms. In the Sustainalytics’ ESG risk metric, 0–10 means negligible, 10–20 is low, 20–30 is medium, 30–40 is high, and 40+ means severe risk, respectively. An industry dummy is included to test with and without industry effects in each model.

5. Empirical Results

5.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation

Table 4 presents the descriptive statistics of the variables. The maximum IR score that a reporter can achieve is 54. Therefore, the average IR quality for 4 years is 42.51 out of 54, with the lowest and highest IR quality score between 32.00 and 54.00. According to the variables of the board of directors, for 4 years, the mean value shows that the average percentage of independent board members is 56.65, the average board size is 10.34, and the average percentage of women board members is 31.05. In other words, in the sample of this study, approximately six of the total number of the board of directors are of independent members and three of them are women. In terms of the variables of the audit committee for 4 years, Table 3 indicates that the average percentage of audit committee independence is 72.90, the audit committee size is 4.02, and the number of audit committee meeting is 5.20. This means that three of the total number of audit committee members are independent. Furthermore, the average ESG risk rating of the sample size is 27.24 and the ESG risk ratings range from 14.25 to 39.95. Considering the Sustainalytics’ ESG risk metric, the ESG risk of the sample size for the 4-year average is medium. In addition, the average value for the number of integrated reports published is 3892, which is in the range from 1 to 8. While the mean value for the voluntary IR in the sample size is 0.37, it is 0.63 for the sustainability committee. This means that most of the firms in the sample publish integrated reports on a voluntary basis and have a sustainability committee. Finally, the natural logarithm of total assets is 22.84 and the ROA is 10.56 for the 4-year average. Although the scoring method was adapted from the IR Framework, Cronbach’s Alpha was also measured and found to be 0.72. This is a reliable level considering Ursachi et al. [107]. In addition, Hair et al. [108] suggested that the variance inflation factor (VIF) and tolerance level should be as follows: VIF < 4 and tolerance > 0.2. Therefore, it is noticed that all these values are within the specified ranges.

Table 4.

Descriptive statistics.

The correlation matrix of the variables used in this study is presented in Table 5. According to Table 5, the correlation coefficient shows that there is a positive correlation between IR quality and the independent variables of the board of directors and the audit committee. In terms of the correlation between IR quality and ESG risk ratings, there is a negative correlation. Regarding the independent variables of this study, a low level of correlation is determined. The highest correlation is found for the audit committee meetings and percentage of audit committee independence with 0.428. Given these results in Table 4, it is proved that this study does not contain multicollinearity. Consequently, the data represent no restrictions for conducting the panel regression analysis.

Table 5.

Correlation of variables.

5.2. Results of Panel Regression

To answer RQ1 and RQ2 and to test the hypothesis of this study, a Panel Estimated Generalized Least Squares (Panel EGLS) analysis is conducted. Before conducting this analysis, a decision must be made considering the usage of a fixed effect versus a random effect regression model, in which Hausman test statistics determine the appropriateness of the regression model. Therefore, in this study, the Hausman test statistic rejected the null hypotheses for the fixed effects model, which means that the random effects model is used in the analysis of each model. After this consideration, the results of the random effect Panel EGLS analysis are presented in the following Table 6 and Table 7.

Table 6.

Results of regressions for Model 1 and 2.

Table 7.

Result of regression for Model 3.

Table 6 lists the results of regressions for Model 1 and 2 considering the inclusion and exclusion of industry effects. In terms of Model 1, the results indicate that a positive and significant association exists between board independence and IR quality, and the hypothesis H1A is accepted. Secondly, the results show that no significance is found between the board size and IR quality. In this context, the hypothesis H1B is rejected. Lastly, the hypothesis H1C is accepted, in which the evidence shows that the percentage of women members on the board is positively and significantly associated with an improvement in IR quality. Therefore, the number of women and independent members on the board is an important factor leading to an increase in the IR quality. For the control variables, while the total asset size and ROA have a positive and significant impact on IR quality, no evidence is found for the number of integrated reports published, voluntary IR, and the existence of a sustainability committee. When we add the industry effect, it is observed that the results do not change for each variable.

Table 6 also provides the results for Model 2. Considering the results of Model 2, a positive and significant relationship exists between audit committee independence and IR quality, and H2A is supported. However, since the result shows that the relationship between the audit committee size and IR quality is not statistically significant, hypothesis H2B is rejected. Finally, positive and significant evidence is presented between audit committee meetings and IR quality, supporting hypothesis H2C. For Model 2, the number of integrated reports published, the IR type, and the presence of a sustainability committee are not contributing factors to IR quality when considered together with the effect of audit committee variables. In contrast, the total asset size and ROA contribute significantly and positively to IR quality. When we add the industry effect and run the results again, as in the first model, no change is observed in the results obtained without the industry effect.

In the light of the results of Model 1 and 2, while the percentage of independent and women members on the board of directors is of great significance for IR quality, the percentage of audit committee independence and the number of audit meetings are critical determinants of IR quality. Vitolla et al. [34] obtained a similar result in terms of the effect of board independence, but unlike their study, we did not observe any significance for the effect of the board size on IR quality. Similarly to our study, Songini et al. [2] considered the board size and number of woman members in their analysis, but they did not find any statistical significance for these variables. Therefore, mixed results were obtained regarding the recent studies, in which our study is believed to provide more consistent results depending on the sample size with a time series. Accordingly, unlike previous studies, the results confirm that board independence and women board members as the board characteristics are more important determinants of IR quality than the board size. These findings are believed to contribute to both corporate governance and the IR literature. From an audit committee perspective, the results of this study expand [58,104]. Similarly to Model 1, in Model 2, audit independence and the number of audit meetings as the characteristics of the audit committee are more crucial factors for IR quality than the audit committee size.

Considering the results of the control variables, no significance was found except the financial determinants as the total asset size and ROA. Therefore, the number of integrated reports published, the fact that integrated reports are prepared on a voluntary basis, and the existence of a sustainability committee are not determining factors for IR quality. In previous studies, reporting quality was addressed as one of the main determinants of the financial performance of a firm, in which it is assessed through the return on assets (ROA), return on equity (ROE), and earnings per share (EPS) as well as Tobin’s Q (Q-ratio) ratios [24,109,110]. Therefore, the results regarding the total asset size and ROA extend the current literature and indicate that achieving the a high IR quality leads firms to better transparency and accountability, which in turn helps to improve financial performance. Lastly, the results also show that none of the industry dummies turned out to be significant, suggesting that there are no significant industry-specific differences for IR quality.

Table 7 lists the findings of Model 3, where the results indicate that a negative and significant relationship exists between the IR quality and ESG risk level of firms. Moreover, among the different control variables, only the total asset size is found to be significant. Therefore, as the quality of the information increases with IR, firms give more importance to their ESG approaches, which leads to a decrease in the level of risk. This reduction in the level of ESG risk has a positive effect on the total asset size of firms. In other words, an improved IR quality pushes firms to be more transparent and accountable, which in turn reduces the ESG risk ratings of firms. Accordingly, these firms are more valuable for the investors. When we added the industry effect to rerun the test again, it was found that the results did not change. Accordingly, no industry specific effect was observed in this relationship. Unlike the results of Conway [66], the results of this paper indicate that an association exists between the ESG rating and IR practice on the basis of the risk level and reporting quality. This is also believed to be related to the nature of the information provided by the IR. This result is not surprising given that a large proportion of the content provided by IR is ESG-related. Moreover, Appiagyei and Donkor [36] found that the IR quality and sustainability performance are related to each other within the South African firms. This result is extended by this paper on the basis of measuring IR quality consistently and considering the ESG risk scores of firms. Furthermore, the fact that the sample of this study consists of IR practitioners from different countries and sectors, rather than focusing only on South African firms, contributes to the consistency and generalizability of the results. Regarding the nature of this paper as panel data, the results are therefore believed to bring novelty to the literature, new and current IR practitioners, various stakeholders, and investors.

6. Further Data Analysis

Endogeneity Check

Depending on the independent variables, the endogeneity problem may arise in empirical research. It is the situation where the factors affecting the dependent variable also affect the independent variables [111]. Moreover, some of the independent variables might be correlated with error terms. In addition, previous studies addressed the possible existence of endogeneity, and these studies are based on the board structure, level of disclosure, IR, and financial performance [112,113,114,115,116]. Therefore, considering the results of these studies, endogeneity can exist between explanatory variables in each model of this paper. To overcome this problem, previous studies have used one-year lagged variables of all explanatory variables to detect endogeneity in causality and simultaneity [117,118,119]. To cope with the endogeneity problem, a series of tests are performed through employing a system generalized method of moments (GMM) technique. The System GMM approach is a leading dynamic panel analysis technique, which was proposed by Hansen [102]. The assumptions of the System GMM are more robust as it takes into account momentary conditions using lagged variables. Accordingly, lagged levels and differences in the explanatory variables are selected to control for potential simultaneity and reverse causality, as recommended in the previous literature. Therefore, the results of this study are repeated, and are presented in Table 8.

Table 8.

Endogeneity check with GMM.

According to Table 8, the application of the GMM technique confirms and strengthens the earlier panel data findings. The diagnostic tests confirm the robustness of the GMM estimations. The Hansen J-test for overidentifying restrictions supports the validity of the instruments used, while the Arellano–Bond tests for autocorrelation show no second-order correlation (AR(2) for each model), indicating that the instruments are both relevant and valid. The GMM results offer additional evidence for the causal relationships proposed in this study, demonstrating that both corporate governance mechanisms and IR quality play crucial roles in improving reporting outcomes and reducing ESG risk ratings.

7. Conclusions and Discussion

This paper analyzed the relationship between IR quality, corporate governance structures considering the board and audit committee characteristics, and ESG risk ratings. The research questions focused on the impact of the board of directors and audit committee characteristics on IR quality (RQ1) and whether a higher IR quality is associated with lower ESG risk ratings (RQ2). The research implications, research limitations, and future research suggestions of this paper are as follows.

7.1. Research Implications

The empirical findings of this study provide strong support for many of the proposed hypotheses and provide meaningful insights into the determinants of IR quality. In particular, this paper confirms that board independence (H1A) and the presence of women on the board (H1C) have a significant positive effect on IR quality, emphasizing the importance of diversity and independent oversight in improving the reliability and comprehensiveness of corporate reporting. In contrast, the board size (H1B) does not show a statistically significant relationship, suggesting that the board’s effectiveness may be influenced by its composition rather than its size. In terms of audit committee characteristics, this paper showed that both audit committee independence (H2A) and the frequency of audit committee meetings (H2C) significantly improve IR quality, while the audit committee size (H2B) has no effect. These results underline that independence and active participation in audit functions are more important than structural size. Additionally, the preparation basis of IR as voluntary or mandatory, the experience of the firms considering the number of published integrated reports, and the existence of a sustainability committee were not related to IR quality. Moreover, the firm size and industry were not contributing elements to the quality of IR. In other words, no differences were observed within the industries considering IR quality. In addition, this paper shows a significant negative relationship between IR quality and ESG risk ratings (H3), implying that firms with a higher IR quality tend to exhibit lower ESG risks. This finding highlights the broader strategic role of IR in promoting transparency, accountability, and sustainable corporate behavior. This study, therefore, supports agency, signaling, legitimacy, and stakeholder theories by demonstrating that governance structures promoting oversight and diversity improve transparency and accountability. IR quality aligns with the agency theory, which emphasizes the role of governance mechanisms in mitigating information asymmetry and enhancing accountability. Similarly, the stakeholder theory is reinforced through the finding that a higher IR quality correlates with a lower ESG risk, indicating that firms responding to diverse stakeholder expectations through transparent reporting are more sustainable and credible.

Practically, the findings suggest firms can strengthen IR quality and reduce ESG risk by enhancing their board composition and audit practices. This highlights IR as a strategic tool for accountability, risk management, and long-term value creation as well. Considering the results together, corporate governance mechanisms, particularly those that promote independence and diversity, appear to be critical characteristics for improving reporting quality and mitigating non-financial risks. It also offers practical implications for policymakers, regulators, and firms seeking to improve sustainability outcomes through governance reforms and improved disclosure practices. First, it is imperative to consider enhancing the board composition. Policy interventions should aim at increasing board independence and diversity, and regulatory authorities or industry associations might promote a more balanced composition of boards which are found to improve IR quality. Secondly, given the significant impacts of the audit committee on IR quality, ensuring and strengthening audit committee independence stands out as very critical. Third, regulations and the IR framework can be aimed at promoting ESG reporting and IR to disclose relevant information about ESG practices, which produces lower ESG risk ratings. This is probably due to the enhanced transparency, accountability, and sustainability objectives resulting from the IR quality.

Overall, our study contributes to the existing literature in several ways. Firstly, it expands upon previous research by considering board of directors and audit committee characteristics as determinants of IR quality within the context of corporate governance in a more complete and consistent manner [1,2,3,58]. Secondly, our study comprehensively measures IR quality by incorporating Guiding Principles, Content Elements, and Fundamental Concepts of the IR framework, providing a more holistic understanding. Therefore, this study brings novelty to the literature on the matter of offering a complete scoring method. Lastly, we explore potential sectoral effects on IR quality, offering insights into industry-specific variations. Moreover, our paper considers the ESG risk ratings and IR quality relationship for the first time. Therefore, improving the IR quality by means of considering the findings related to the effect of the board of directors and the audit committee has encouraged firms to disclose their ESG-specific information. So that it is a critical driver of transparency and accountability, which lead firms to improve their ESG performance and lower their ESG risk ratings, respectively. Correspondingly, these firms are more valuable in the market, where this is expected to affect the decision-making process of investors. In this regard, IR quality is of great importance.

7.2. Research Limitations

This study is subject to several limitations. First, the sample is limited to firms that publish integrated reports, which may lead to a selection bias by excluding non-reporting firms. Second, while the panel data approach strengthens the findings, the observational nature of this study limits causal inferences. Third, the measurement of the IR quality, although based on the IR Framework, may still contain some subjectivity. Next, this study has a broad geographical scope, which encompasses firms from various countries without focusing on a specific national or regional context. While this approach enhances the generalizability of the findings, it may overlook significant variations in ESG reporting practices influenced by local regulations, cultural factors, and market conditions.

7.3. Future Research Suggestions

Future research can expand the scope to include firms that do not publish integrated reports to investigate barriers to IR adoption. Comparative studies across different regulatory environments or regions may also provide deeper insights into institutional influences on IR quality. Moreover, future studies can explore the dynamic effects of board and audit committee reforms over time or examine other governance factors, such as the CEO duality or ownership structure. Finally, qualitative approaches can complement quantitative findings by investigating how firms internally manage and perceive integrated reporting processes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.C. and M.S.; methodology, M.S.; formal analysis, M.S.; investigation, M.C.; data curation, M.S.; writing—original draft preparation, M.C. and M.S.; writing—review and editing, M.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

IR quality measurement.

Table A1.

IR quality measurement.

| No. | Fundamental Concepts | Absence of Information | Poor | Balanced | Excellent |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Value: value that is created by a corporation over time for the corporation itself; shareholders and stakeholders are addressed. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 2 | The capitals: the major capitals that are used by corporations are explained, such as financial, manufactured, intellectual, human, social and relationship, and natural. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 3 | The value creation process is explained, which is based on business models, capital as inputs, business activities, outputs, and outcomes. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Guiding Principles | |||||

| 1 | Strategic focus and future orientation: information is provided on an organization’s strategy and how value is created over the short, medium, and long term, and the effects of capitals are explained, which relates with an organization’s strategy. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 2 | Connectivity of information: a holistic picture is provided for the corporation, which contains combinations, interrelatedness and dependencies between factors, and Content Elements. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 3 | Stakeholder relationship: information is provided, in which the relationships between major stakeholders are explained. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 4 | Materiality: information that is presented is about relevant matters about how a corporation’s ability to create value over time is affected. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 5 | Conciseness: information is presented in a concise manner (length of reports should not be very long) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 6 | Reliability and completeness: information is presented in a complete manner based on both positive and negative sides, which is expected to be free from material error. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 7 | Consistency and comparability: information is presented in a consistent manner, which is expected to allow comparisons between other integrated reports. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Content Elements | |||||

| 1 | Organizational overview and external environment: information is presented about what the corporation does and under which conditions they operate depending on the external environment. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 2 | Governance: information is presented about the governance structure of the corporation (e.g., board diversity, culture, ethics, and values) and how it affects the value creation over time. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 3 | Business Model: information is presented about the business model of the corporation, which explains how inputs are transformed into outputs and outcomes by means of business activities in order to create value. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 4 | Risks and opportunities: information is presented about risks and opportunities (e.g., internal and external) that affect the ability of a corporation to create value, and the ways of dealing with risks are explained. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 5 | Strategy and resource allocation: information is presented on where the corporation wants to go and how this is achieved through assigning and managing assets. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 6 | Performance: information is presented about how successful the corporation is to achieve goals and objectives by means of both the qualitative and quantitative outcomes. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 7 | Outlook: information is presented about the external environment regarding the challenges and uncertainties that are experienced by the corporation, in which the possible implications and expectations are discussed. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 8 | Basis of preparation and presentation: information is presented about the process of how a corporation decides what matters are covered by IR and how these matters are quantified and evaluated. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

0 = absence of information; 1 = poor information; 2 = balanced information partially supported by quantitative data; and 3 = excellent information supported by quantitative data. Source: adapted from the IIRC (2021) [23].

References

- Pistoni, A.; Songini, L.; Bavagnoli, F. Integrated reporting quality: An empirical analysis. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 489–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Songini, L.; Pistoni, A.; Tettamanzi, P.; Fratini, F.; Minutiello, V. Integrated reporting quality and BoD characteristics: An empirical analysis. J. Manag. Gov. 2022, 26, 579–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agustia, D.; Sriani, D.; Wicaksono, H.; Gani, L. Integrated reporting quality assessment. J. Secur. Sustain. Issues 2020, 10, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, C.S.; Guay, W.R.; Mehran, H.; Weber, J.P. The role of financial reporting and transparency in corporate governance. Frbny Econ. Policy Rev. 2016, 22, 107–128. [Google Scholar]

- Eccles, R.G.; Saltzman, D. Achieving sustainability through integrated reporting. Stanf. Soc. Innov. Rev. 2011, 9, 56–61. [Google Scholar]

- Fosso Wamba, S.; Akter, S.; Trinchera, L.; De Bourmont, M. Turning information quality into firm performance in the big data economy. Manag. Decis. 2019, 57, 1756–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, A. Corporate governance and agency conflicts. J. Account. Res. 2008, 46, 1143–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healy, P.M.; Palepu, K.G. Information asymmetry, corporate disclosure, and the capital markets: A review of the empirical disclosure literature. J. Account. Econ. 2001, 31, 405–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. G20/OECD Principles of Corporate Governance; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fama, E.F.; Jensen, M.C. Separation of ownership and control. J. Law Econ. 1983, 26, 301–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M.C.; Meckling, W. Theory of the firm: Managerial behaviour, agency costs and ownership structure. J. Financ. Econ. 1976, 3, 305–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beske, F.; Haustein, E.; Lorson, P. Materiality analysis in sustainability and integrated reports. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2019, 11, 162–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prado-Lorenzo, J.M.; Gallego-Alvarez, I.; Garcia-Sanchez, I.M. Stakeholder engagement and corporate social responsibility reporting: The ownership structure effect. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2009, 16, 94–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, J.F. Corporate Governance and Accountability; John Wiley and Sons: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bathala, C.T.; Rao, R.P. The determinants of board composition: An agency theory perspective. Manag. Decis. Econ. 1995, 16, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barako, D.G.; Hancock, P.; Izan, H.Y. Factors influencing voluntary corporate disclosure by Kenyan companies. Corp. Gov.: Int. Rev. 2006, 14, 107–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lary, A.M.; Taylor, D.W. Governance characteristics and role effectiveness of audit committees. Manag. Audit. J. 2012, 27, 336–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; García-Meca, E.; Martinez-Ferrero, J. Do board and ownership factors affect Chinese companies in reporting sustainability development goals? Manag. Decis. 2023, 61, 3806–3834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosati, F.; Faria, L.G. Addressing the SDGs in sustainability reports: The relationship with institutional factors. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 215, 1312–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erin, O.A.; Olojede, P. Do nonfinancial reporting practices matter in SDG disclosure? An exploratory study. Meditari Account. Res. 2024, 32, 1398–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanchel, I.; Lassoued, N.; Baccar, I. Sustainability and firm performance: The role of environmental, social and governance disclosure and green innovation. Manag. Decis. 2023, 61, 2720–2739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, C.A. The Sustainable Development Goals, Integrated Thinking and the Integrated Report; Integrated Reporting (IR); International Integrated Reporting Council: London, UK, 2017; pp. 1–52. [Google Scholar]

- International Integrated Reporting Framework (IIRC). International <IR> Framework. 2021. Available online: https://integratedreporting.ifrs.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/InternationalIntegratedReportingFramework.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- Conway, E. Quantitative impacts of mandatory integrated reporting. J. Financ. Report. Account. 2019, 17, 604–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sariyer, G.; Taşkın, D. Clustering of firms based on environmental, social, and governance ratings: Evidence from BIST sustainability index. Borsa Istanb. Rev. 2022, 22, 180–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widyawati, L.A. Systematic literature review of socially responsible investment and environmental social governance metrics. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 619–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churet, C.; Eccles, R.G. Integrated reporting, quality of management and financial performance. J. Appl. Corp. Financ. 2014, 26, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumay, J.; Bernardi, C.; Guthrie, J.; Demartini, P. Integrated reporting: A structured literature review. Account. Forum 2016, 40, 166–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]