Abstract

In today’s world, there are numerous challenges all over the world because of human lifestyles. Therefore, raising awareness of sustainable living is crucial to developing ways for everyone to live better while meeting both present and future generations’ environmental, social, and economic needs. In this context, the aim of the current research was to investigate the effects of the learn–think–act-based Education for Sustainable Development Goals (ESDG) program on secondary school students’ sustainable living awareness. A single-group pre- and post-test model was used in this research. The research group consisted of 34 seventh-grade students enrolled in the “Environmental Education and Climate Change” elective course at a public school in Istanbul, Türkiye. The data were collected using the Sustainable Living Awareness Scale (SLAS). A paired-sample test was used for data analysis. The findings show that there were statistically significant differences between the pre- and post-test total and sub-factor scores of the secondary school students’ sustainable living awareness, with the post-test scores being higher. In other words, the results show that learn–think–act-based ESDG can be an effective way to develop students’ sustainable living awareness.

1. Introduction

We live in a time where the world is facing numerous challenges that are difficult to overcome. The drivers of these problems are the consequences of the lifestyles of billions of humans [1,2]. As humans, our lifestyle choices impact our world profoundly. That is, every day, we make choices in our lives that cause problems, like poverty, hunger, lack of water, unemployment, environmental pollution, climate change, harm to other species, and many more. All of these challenges may seem insurmountable, but there is still a chance to solve them. Every one of us can do something to take care of our planet. From what we eat to how we use resources, like water, energy, etc., there are many things we can do to reduce our footprint and leave a more sustainable world for all living things, including people, plants, and animals. Our individual actions play an important role in addressing these challenges, but we cannot achieve them alone. Therefore, developing the sustainable living awareness of students at an early age is crucial to find ways to protect and sustain our world’s resources while improving the welfare of all living things. Sustainable living awareness, as a component of an individual’s attempt to adopt more sustainable and low-impact habits, is identified as a positive sign of behavioral change and is being requested by governments and industries [3].

To achieve a more sustainable world, as described in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), individuals should be raised as conscious citizens who have awareness about sustainable living. In other words, they should be trained as sustainability changemakers. This vital task can be ensured using the Education for Sustainable Development Goals (ESDG) program [2,4,5,6]. ESDG (also known as global citizenship education) is an educational approach that focuses on global issues and their solutions, as outlined by the SDGs [7]. ESDG can help students grasp the importance of the world’s resources for us, how they should be used, and how they play a crucial role for both our existence and that of future generations. In addition, ESDG can help develop students in many aspects, such as their knowledge, attitudes, values, skills, worldviews, and behaviors, which are necessary for them to be able to contribute to more sustainable ways of living [8,9,10,11,12]. That is, ESDG prepares students and communities as life-long learners and transformative changemakers by actively engaging them in the different perspectives of the SDGs. Teaching sustainable ways of living to students, especially at an early age, can help them form habits, find solutions for better living, and empower them to be decision makers for a sustainable future [3,5,13,14,15,16,17,18]. In order to adopt sustainable life principles and to transform them into behavior, that is, to transform them into a sustainable lifestyle, research is needed to develop appropriate educational programs and teaching materials [19,20,21,22]. However, there is a lack of educational materials to help raise students’ sustainable living awareness, especially at the K–12 levels, in the literature [23,24,25]. Learn–think–act-based teaching materials in ESDG can support students in becoming aware of the world’s problems and understanding their role in making our world a more sustainable place [26,27]. Therefore, the current study aims to develop secondary school students’ awareness of sustainable living through learn–think–act-based ESDG. In this context, the research question was as follows:

- Is there a statistically significant difference between students’ sustainable living awareness before and after the introduction of learn–think–act-based ESDG?

2. Research Background

2.1. Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

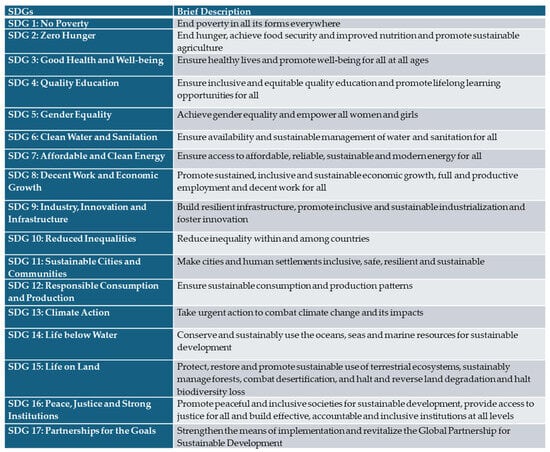

On 25 September 2015, the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) declared 17 SDGs, including 169 sub-targets, in order to transform our world and direct humanity toward a sustainable way of living [28]. The SDGs (also described as the Global Goals) are a worldwide call for action to put an end to global challenges that our global society is facing and to guarantee the welfare of all living things by 2030 [26,28]. The goals address many vital issues under environmental, economic, and social topics [2]. Figure 1 shows the SDGs and their brief descriptions [28].

Figure 1.

SDGs and brief descriptions [28].

2.2. Education for Sustainable Development Goals (ESDG)

Achieving the SDGs requires a transformation in our thinking and actions, and eventually a shift toward sustainable lifestyles and changes in production and consumption patterns [29]. Only education at all levels can lead to these critical changes [30]. When teaching SDGs, traditional teaching methods are insufficient for fostering a profound understanding that will bring about behavioral changes and action because SDGs are multidimensional and context-specific [31]. There is a need for a holistic approach that will empower people with competencies to help solve local and global issues challenging society now and in the future [32,33].

Education for Sustainable Development Goals (ESDG) is an action competence approach that encourages individuals to take actions for complex issues connected to the SDGs [34,35]. That is, ESDG aims to develop the knowledge, skills, and competencies that will help individuals take their own actions by considering their present and future economic, environmental, and social effects on both local and global aspects [2,36,37,38,39,40,41,42]. ESDG reflects the active role of learners in solving and addressing global issues, ultimately empowering them to become proactive global contributors to a more peaceful, just, secure, inclusive, and sustainable world [43]. This means that ESDG is a reflective and transformative process that aims to integrate the perceptions and values of sustainability into not only education systems but also individuals’ everyday personal and professional lives. Therefore, the main goal and desired outcome of ESDG is to promote wider social learning about sustainable living and sustainable decision making throughout life [6,7]. In other words, it encourages people to make smart and responsible choices that create a sustainable and better future for everyone [44,45,46].

Learn–Think–Act-Based ESDG

ESDG is an essential element for improving sustainable lifestyles because it enables people to improve their skills to move toward a sustainable future [47,48]. In other words, ESDG can promote sustainable decision making and sustainable living awareness when sustainable living-based teaching materials are embedded into education on SDGs. This process includes designing practical ethics-led learning activities focused on living sustainably, with specific goals in mind [49,50,51]. Since sustainable living activities inherently foster real-life experiences, they enable students to think about the experiences of other living beings and to develop skills like multiple perspective thinking and systems thinking [52,53,54,55,56,57]. By engaging in ethics-led learning activities, students can evaluate the value of their learning and explore locally appropriate and sustainable ways of living. Teachers can teach local or global subjects by centering issues and matters of concern [58]. In this way, students can obtain the necessary information, and they are expected to investigate the concepts more by applying them to local or global issues they face in their life. When students integrate subject knowledge with knowledge and experiences from their specific contexts, they can make an effort to find solutions for both local and global issues [58].

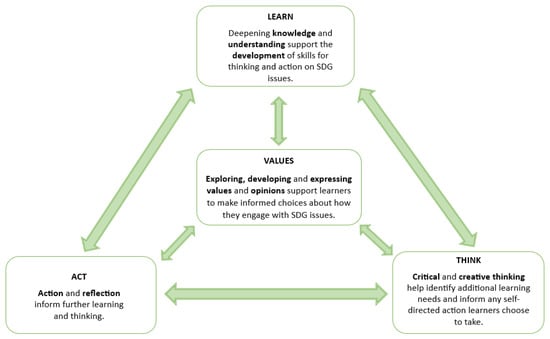

The learn–think–act approach to ESDG can help improve students’ sustainable living awareness. Thanks to this approach, students can learn about local and global issues, think about these issues critically, try to find solutions for problems, and act sustainably [26,27]. Figure 2 shows the learn–think–act framework [26]. Using the learn–think–act framework to teach the SDGs prompts students to consider their behaviors and actions deeply and to explore new ways of living to become responsible and active global citizens with high sustainable living awareness [59]. Therefore, in this research, this approach was used to teach SDGs to students.

Figure 2.

The learn–think–act framework [26].

2.3. Sustainable Living Awareness

Current choices and activities contribute to unsustainable development and cause many challenges, such as environmental problems (e.g., pollution, climate change, deforestation, loss of biodiversity, etc.), economic problems (e.g., unemployment, low income, lack of energy, etc.) and social problems (e.g., hunger, lack of education, etc.) [60,61,62]. This means that the current lifestyles of people are unsustainable. Our future depends on how we prefer to live now and how we care for our world as global consumers, such as how we run our homes, how we work, what food we eat, how we get around, what we buy, etc. [63,64,65]. Therefore, individuals should be raised to respond to complex issues in a sustainable way and to participate in decision-making processes, which may help move society toward achieving the Sustainable Development Goals. The need to encourage a sustainable lifestyle has officially been discussed by the UNGA [66]. The report underlines that sustainable problems cannot be addressed by increasing efficiency; they require changes in behaviors. Production systems have increased their efficiency and now generate fewer negative impacts on the environment [67], but inventions cannot ensure that users select environmentally friendly products and/or services [68]. Therefore, improving people’s decision making for sustainability and integrating sustainable living principles across society, in line with the Sustainable Development Goals, should become the new normal for people everywhere [66,69]. If people are more informed and motivated, they can strive to adopt and promote more responsible and sustainable ways of living [3,70]. Living within the limits of the world can make a better quality of life available for all in an equitable and just way, not only now and but also in the future [71,72,73]. Sustainable living conserves the diversity and vitality of the world and provides real improvements in the quality of life of humans [74,75,76,77]. Therefore, enhancing sustainable living awareness is important for achieving the SDGs. Sustainable living or sustainable lifestyle refers to understanding how our living or lifestyle preferences affect our world and finding solutions for all living beings to live better, lighter, and more sustainably [28,78]. In other words, sustainable living is basically the practical application of sustainability to lifestyle decisions and choices. Sustainable living or lifestyles are considered ways of living, choices, and behaviors that minimize environmental deterioration (CO2 emissions, use of natural resources, pollution, and waste), while supporting equitable socio-economic development and better quality of life for all [79]. That is, sustainable living refers to maintaining balance in triple-bottom-line terms while meeting present environmental, social, and economical needs without compromising these factors for future generations [80,81]. This involves changing our diets, what we buy, how we travel, and how we use resources, like water and energy [82]. Aspects of sustainable living and lifestyles have been clearly emphasized in the SDGs (e.g., Goal 4.7—Quality Education and Goal 12.8—Responsible Consumption and Production). The SDGs aim to empower people with the necessary knowledge and awareness to achieve the SDGs and live in harmony with nature [28,83].

The traditional education system generally emphasizes values that influence people to consume rather than conserve [31,84]. Achieving sustainable lifestyles requires in-depth visioning, design, and implementation of ESDG at different levels [84,85]. ESDG is acknowledged as a vital element for achieving sustainable living because it not only equips individuals with the required knowledge, competencies, and skills but also integrates values inherent in the Sustainable Development Goals [86].

3. Methodology

3.1. Design of Research

The aim of the present research was to investigate the effect of learn–think–act-based ESDG on students’ sustainable living awareness. In order to achieve this aim, a single-group pre- and post-test design was used. This design is a quantitative research method and involves measuring a single group both before and after exposure to the process [87,88,89]. In the present research, the Sustainable Living Awareness Scale was applied as a pretest at the beginning of the “Environmental Education and Climate Change” course. For 8 weeks, a learn–think–act-based ESDG program was taught to the students. In order to investigate the effect of this instruction on students’ sustainable living awareness, the scale was measured again in a post-test after 8 weeks.

3.2. Sample

The sample of the current research involved 34 seventh-grade students who took the elective course “Environmental Education and Climate Change” at a state school in Istanbul, Türkiye. The participants included 17 girls and 17 boys. These students voluntarily participated in this elective course, which involved ESDG for the first time.

3.3. Implementation

At the beginning of the “Environmental Education and Climate Change” course, the 34 seventh-grade students were assessed on the Sustainable Living Awareness Scale (SLAS) to determine their awareness about sustainable living. The science teacher started implemented the learn–think–act-based ESDG program in the second week. The implementation of the learn–think–act-based ESDG program lasted eight weeks (2–3 h per week). The teacher taught all the SDGs (1–17) by using the learn–think–act approach for 8 weeks. During the “learn” part, the teacher provided theoretical knowledge and showed videos about the SDGs to the students. During the “think” part, the students engaged with both local- and global-based activities to think about the SDGs critically. Every activity during the think part involved both information about local cases in Türkiye and global cases from different parts of the world. For example, “What’s on our plate? Every plate tells people’s stories” (SDG 2 activity) includes information about hunger and compares Türkiye with different countries. Another example is “Reduce, reuse, recycle for a better life! Understanding the challenge of finite resources” (SDG 12 activity), which covers information about strategies for recycling in both Türkiye and other countries. During the “act” part, the students found solutions for challenges described in the SDGs through discussion, and they watched videos about acting to achieve the SDGs in meaningful and appropriate ways. Table 1 shows the implementation parts of the learn–think–act-based ESDG program. In addition, Table 2 shows examples of the content of the learn–think–act-based ESDG program (SDG 4: Quality education) (objectives, information, videos, and activities). Figure 3 shows photos from the implementation process. More detailed information about the learn–think–act-based ESDG procedure and the contents of the teaching procedure can also be examined in the article by Ref. [90]. At the end of the course, the students were assessed again using the “Sustainable Living Awareness Scale (SLAS)” to determine their post-education awareness of sustainable living.

Table 1.

Implementation of the learn–think–act-based ESDG program.

Table 2.

A part of the learn–think–act-based ESDG program (SDG 4: Quality education).

Figure 3.

Photos from the implementation portion.

3.4. Data Collection

The data for the current research were collected using the “Sustainable Living Awareness Scale (SLAS)” developed by Akgul and Aydogdu [19]. The SLAS consists of 20 items. The scale is a 3-point Likert type, and each of the items in the scale was graded as “Agree (3)”, “Undecided (2)”, or “Disagree (1)”. The scale has a 3-factor structure, including social, economic, and environmental factors. The environmental factor is composed of 7 items, the economic factor consists of 5 items, and the social factor includes 8 items. A minimum of 20 and a maximum of 60 points can be obtained from the scale. As can be observed in Appendix A, the items of the scale were developed by researchers based on their cultural relevance by considering the current literature about sustainable living [19]. This means that the items can be understood by secondary school students from different cultures and countries. In determining the awareness of students about sustainable living, an SLAS score close to 40 points with indicates a medium level, and a score close to 60 points indicates a high level [19]. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of the SLAS was found to be 0.77 by the developers of the scale [19]. In the current research, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was calculated as 0.78. This value confirms internal consistency and reveals that the SLAS is a reliable measurement tool.

3.5. Data Analysis

A paired-samples t-test, as a parametric test, was conducted to analyze the data in the current research. The paired (dependent)-samples t-test is a statistical method to test if the mean difference between pairs of measurements is zero or not [91]. But before conducting the test, several assumptions for the paired/dependent-samples t-test were checked. Firstly, the dependent variable was measured at the interval level, and the pre- and post-test scores were derived from the same instrument, which produced continuous data. Secondly, dependent observations were used. This means that each participant had two scores (pre- and post-test scores) that were matched or paired. Thirdly, the participants were randomly sampled from the population. Fourthly, the normal distribution and outliers of the data were checked. Because the difference in the scores of the two related measures demonstrated normal distribution and did not contain any significant outliers (the values of skewness and kurtosis were close to zero, the Shapiro–Wilk test scores were greater than 0.05, the histogram shows a normal distribution and no outliers), a paired-samples t-test, as a parametric test, was conducted to analyze the data.

3.6. Ethical Issues

This study was conducted with the approval of the Ethics Committee of Yıldız Technical University. Informed consent, including the voluntariness of subjects and an informed consent form, was obtained from all participants, and permission from their parents was obtained through a “Child consent form for research purposes” before the research was conducted. Moreover, the students were given information about the research process (ESDG implementation, data collection, etc.) and the course contents in detail. In addition, they were informed that this implementation was a part of the research and their participation was voluntary. Students were informed that they had an option to not participate in the research, and they could withdraw from the study if they wanted. Furthermore, the students were informed that nobody would have access to their data, ensuring their privacy. To ensure anonymity, the participants’ personal knowledge and names were not used and not shared in the research. Moreover, there was not any harm, risk, or disadvantage posed to the students in this study since necessary precautions in the classroom were taken by the researcher and the science teacher.

4. Results

In this study, the effects of the learn–think–act-based ESDG approach on students’ awareness about sustainable living were examined. The pre- and post-test results concerning the total and sub-factor scores of the SLAS are presented in Table 3 and Table 4. According to the pre- and post-test scores, there were statistically significant differences, the total post-test scores (t(33) = −9.685, p < 0.05) and the sub-factor post-test scores being higher (social factor: t(33) = −8.106; environmental factor: t(33) = −8.731; economic factor: t(33) = −6.025, p < 0.05).

Table 3.

Paired samples statistics.

Table 4.

Paired differences in pre- and post-test results of students’ sustainable living awareness.

The results show that the students’ total scores for their sustainable living awareness were at a medium level (M = 41.50) at the beginning of the course. After the learn–think–act-based ESDG program, the students’ sustainable living awareness was further developed and reached a high level (M = 55.15). The effect size (Cohen’s d value) of the current study was calculated as 1.66. If the Cohen’s d value is greater than 0.8, this indicates a large effect [87,91]. Such effect sizes are generally considered to be clinically or practically important differences [87,91]. That is, there was a significant difference between the pre- and post-test scores of the students’ sustainable living awareness.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

The aim of the current research was to investigate the effect of learn–think–act-based ESDG on the development of students’ sustainable living awareness. The results indicate that learn–think–act-based ESDG is effective for developing secondary school students’ awareness of sustainable living. The effect size in the current study shows that the learn–think–act-based ESDG program had a larger effect on the students’ sustainable living awareness than what has been reported in meta-analyses of other ESD interventions. The reason may be that learn–think–act-based ESDG can engage students in real-life experiences. This type of learning can be more concrete and permanent for secondary school students because they not only learn the issues theoretically but they also think about and discuss these issues and find ways of transforming their theoretical knowledge into action on their own.

In the literature, there are several studies that show the effects of different implementations on students’ sustainable living awareness. All these studies support the results of the current research. For example, Yuzbasıoglu [92] revealed that students’ awareness of sustainable living increased significantly as a result of interdisciplinary activities on the overall scale and in the social, economic, and environmental sub-dimensions of the scale. In addition, it was found in another study that activities for sustainability awareness significantly increased the sustainable living awareness levels of the students [93]. Another study’s findings indicate that environmental education positively improved students’ awareness of sustainable living [94]. Piao and Managi’s [95] results also support the results of the current research. They revealed in their study that higher educational levels increased the behaviors of sustainable living, like consuming recycled goods, purchasing energy-saving household products, conserving electricity, and separating their waste. Some studies have indicated that schools that implemented Education for Sustainable Development had a positive effect on the pupils’ sustainability consciousness [96,97].

Addressing the Sustainable Development Goals can promote profound lifestyle changes. Engaging school children with the issues addressed by the SDGs can develop their sustainable lifestyles [83]. The goal at the center of ESDG is to empower and motivate learners to assess and change their behaviors and take actions toward achieving the SDGs. This enables learners to link local realities to the global context by encouraging them to think critically, make decisions collaboratively, and build future scenarios. ESDG is an education for sustainable lifestyles that emphasizes how our daily choices are connected to the health of our society, the resilience of our ecosystems, and the global issues we face today [52,98]. That is, it involves learning about the principles of moderation and sufficiency as a means of curbing social, economic, and environmental imbalances. ESDG is vital to raise the awareness and actions of individuals to address the impacts of our lifestyle choices and prepare us for sustainable living in the 21st century as global citizens [99].

Unfortunately, as humanity, the way we live is not sustainable, and we are depleting the planet’s resources. Promoting sustainable development and establishing cooperative sustainable living necessary to sustain the world can be achieved with the development of education at the broad population level [95]. Achieving sustainable living is a vital step toward reaching the SDGs. In order to achieve sustainable living, topics, modules, themes, courses, and degrees about Education for Sustainable Development Goals should be included in curriculums. Schools share the responsibility of preparing their students for the major challenges of the 21st century [100]. Integrating strategies of sustainable living into curriculums of all levels of education can raise students’ awareness of local and global issues and have positive implications for society by transforming attitudes and behaviors toward these important issues, with the potential to improve quality of life. Similar to the present research, researchers and educators should develop and adapt teaching resources and, most crucially, develop practical activities that encourage students to reflect on their choices, attitudes, and behaviors to promote maximum interaction in sustainable lifestyles [55,101]. Existing efforts to develop strategies or policies on ESDG with multi-stakeholder approaches require further strengthening and coordination. To integrate ESDG more fully into education, the contents and organization of education programs must be developed with all key stakeholders, such as students, teachers, local governmental and non-governmental organizations, and ESDG experts [29].

People’s choices for sustainable living are important, but many external factors may limit such choices. However, an important point is that individuals should be aware of their own responsibilities by grasping the importance of global multi-stakeholder partnerships and the shared accountability for achieving the Sustainable Development Goals. Put differently, the first necessary step in promoting sustainable lifestyles depends on raising public awareness of what such lifestyles include, allowing for an increased involvement of local society and the general public in a collaborative effort to decrease the human impact on the world [102]. Learning is the key for all of us to find solutions and create a more sustainable world. Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals is not a destination, but a journey. We must learn to live to sustain our world!

Limitations of This Research and Suggestions for Future Studies

One of the most important limitations of the current research is the limited number of samples, since the “Environmental Education and Climate Change” course is an elective course and has a limited capacity. In addition, this elective course is not available in every school in Türkiye and only offered in some state and private schools. In future studies, research can be conducted with more students or other groups, and thus, the validity and generalizability of this study can be developed. In this study, the effects of learn–think–act-based ESDG on the students’ sustainable living awareness were explored with a single-group pre- and post-test model since there was only one class that offered the “Environmental Education and Climate Change” course in the school chosen for the research. The small number of participants and lack of control group may limit the generalizability of the research. By conducting this research with a pre-test and post-test experimental design with a control group, the reliability, validity, and generalizability of the results can be improved in future studies. Furthermore, only a quantitative research method and a three-point Likert scale were used in this research because of the limitations of scales in the current literature. This can cause potential bias (e.g., social desirability bias), central tendency bias, acquiescence bias, limited depth of insight, response style differences, ambiguity in interpretation, an inability to capture complexity, and confounders (e.g., concurrent environmental campaigns in Istanbul) in this research. In order to obtain in-depth results about students’ sustainable living awareness and the effects of implementation, Likert-type scales with five or more points and more items can be developed and used, and even better research can also be conducted with qualitative or mixed-method approaches. The current research shows the results of an 8-week learn–think–act-based ESDG implementation. By designing longitudinal studies, researchers can repeatedly examine the same individuals to detect any changes that might occur over a period of time [103,104,105]. There is a need for follow-up assessments to evaluate to what extent students change their behaviors and apply strategies for sustainable living in their lives. This important point should be taken into consideration in future studies. Despite these limitations, the current study serve as a pioneering effort and contribute to the current literature in terms of providing important results to researchers, science educators, and curriculum experts about the development of sustainable living awareness of secondary school students, who are the future shapers of a sustainable world.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Yıldız Technical University (protocol code 20230201893, date of approval 2 February 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved through a “Voluntariness of subjects and informed consent form” and obtained from their parents through a “Child consent form for research purposes” before the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Part of this study was presented at the NAAEE 2023—North American Association for Environmental Education—20th Annual Research Symposium, held in the United States of America virtually on 12 October 2023.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

| ESDG | Education for Sustainable Development Goals |

| UNGA | United Nations General Assembly |

| UNESCO | United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization |

| SLAS | Sustainable Living Awareness Scale |

Appendix A. Some Items in the Sustainable Living Awareness Scale (SLAS)

Table A1.

Some items in the Sustainable Living Awareness Scale (SLAS).

Table A1.

Some items in the Sustainable Living Awareness Scale (SLAS).

| Sub-Factors of SLAS | Item in SLAS |

|---|---|

| Social | 2. Poverty and hunger in the world are increasing at the same rate in every country (negative item). 5. The increase in the population of the country is a sign of strength (negative item). |

| Environmental | 13. The extinction of plant and animal species in nature directly affects sustainable life (positive item). 14. Environmental problems only affect the region where it is located (negative item). |

| Economic | 16. The inequal distribution of income in the world increases the crime rate (positive item). 20. It is possible to produce electrical energy using waste materials (positive item). |

References

- Pasupa, S.; Pasupa, K. The potential of digital storytelling in encouraging sustainable lifestyle. In Proceedings of the SUIC’s 15th Anniversary Conference and Exhibition, Bangkok, Thailand, 19–20 October 2017; pp. 263–270. [Google Scholar]

- Pauw, J.B.-d.; Gericke, N.; Olsson, D.; Berglund, T. The Effectiveness of Education for Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2015, 7, 15693–15717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrova, A.; Vaishar, A.; Šťastná, M. Preparedness of Young People for a Sustainable Lifestyle: Awareness and Willingness. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badea, L.; Șerban-Oprescu, G.L.; Dedu, S.; Piroșcă, G.I. The Impact of Education for Sustainable Development on Romanian Economics and Business Students’ Behavior. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandell, K.; Öhman, J.; Östman, L.; Billingham, R.; Lindman, M. Education for Sustainable Development: Nature, School and Democracy; Studentlitteratur: Lund, Sweden, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Wals, A.E.J. Learning Our Way to Sustainability. J. Educ. Sustain. Dev. 2011, 5, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Flaherty, J.; Liddy, M. The Impact of Development Education and Education for Sustainable Development Interventions: A Synthesis of the Research. Environ. Educ. Res. 2018, 24, 1031–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, K.; Jagers, S.C.; Lindskog, A.; Martinsson, J. Learning for the Future? Effects of Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) on Teacher Education Students. Sustainability 2013, 5, 5135–5152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, S.; Gilg, A. Sustainable lifestyles: Framing environmental action in and around the home. Geoforum 2006, 37, 906–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munkebye, E.; Scheie, E.; Gabrielsen, A.; Jordet, A.; Misund, S.; Nergård, A.; Bergljot, A.B. Interdisciplinary primary school curriculum units for sustainable development. Environ. Educ. Res. 2020, 26, 795–811. [Google Scholar]

- Rickinson, M.; Lundholm, C.; Hopwood, N. Environmental Learning: Insights from Research into the Student Experience; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Warburton, K. Deep Learning and Education for Sustainability. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2003, 4, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiting, S. Issues for Environmental Education and ESD Research Development: Looking Ahead from WEEC 2007 in Durban. Environ. Educ. Res. 2009, 15, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, G.W.; Moon, M.J.; Kaiser, F.G. The development of children’s environmental attitude and behavior. Global Environ. Chang. 2019, 58, 101947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huckle, J.; Sterling, S.; Sterling, S.R. Education for Sustainability; Earthscan: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Kiss, G.; Lazányi, O.; Taxner, T.; Veress, T.; Neulinger, Á. The transformation of sustainable lifestyle practices in ecoclubs. Clean. Respons. Consum. 2024, 13, 100189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, S.; Kaiser, F.G.; Arnold, O. The critical challenge of climate change for psychology: Preventing rebound and promoting more individual irrationality. Eur. Psychol. 2014, 19, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soydan, S.B.; Samur, A. Validity and reliability study of environmental awareness and attitude scale for preschool children. Int. Electron. J. Environ. Educ. 2017, 7, 78–97. [Google Scholar]

- Akgul, F.A.; Aydogdu, M. Development of Sustainable Living Awareness Scale for Middle School Students. Trakya J. Educ. 2020, 10, 378–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer-Estévez, M.; Chalmeta, R. Integrating Sustainable Development Goals in educational institutions. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2021, 19, 100494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal Filho, W.; Raath, S.; Lazzarini, B.; Vargas, V.R.; de Souza, L.; Anholon, R.; Quelhas, O.L.G.; Haddad, R.; Klavins, M.; Orlovic, V.L. The role of transformation in learning and education for sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 199, 286–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, P.; Galaz, V.; Boonstra, W.J. Sustainability transformations: A resilience perspective. Ecol. Soc. 2014, 19, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.K. Possibilities and Challenges of Education for Sustainable Development in Korean Schools. Internat. Textbook Res. 2008, 30, 608–620. [Google Scholar]

- Mckeown, R. Education for Sustainable Development Toolkit; Waste Management Research and Education Institution, University of Tennessee: Knoxville, TN, USA, 2002; Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000152453 (accessed on 7 January 2025).

- Venkataraman, B. Education for Sustainable Development. Env. Sci. Policy Sustain. Dev. 2009, 51, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OXFAM. The Sustainable Development Goals: A Guide for Teachers; Oxfam GB: Oxford, UK, 2019; Available online: https://oxfamilibrary.openrepository.com/bitstream/handle/10546/620842/edu-sustainable-development-guide-15072019-en.pdf?sequence=4&isAllowed=y (accessed on 25 February 2024).

- Putman, M.; Byker, E.J. Global Citizenship 1-2-3: Learn, Think, and Act. Kappa Delta Pi Rec. 2020, 56, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations (UN). Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; Resolution Adopted by the General Assembly on 25 September 2015; UN: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/ (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Rieckmann, M. Education for Sustainable Development Goals: Learning Objectives; UNESCO Publishing: Paris, France, 2017; Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000247444 (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- United Nations Educational, Scientifc and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). Issues and Trends in Education for Sustainable Development; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, N.J. The Earth’s Blanket: Traditional Teachings for Sustainable Living; University of Washington Press: Seattle, WA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Gadotti, M. Education for sustainability: A critical contribution to the Decade of Education for Sustainable Development, Green Theory and Praxis. J. Ecopedagogy 2008, 4, 15–64. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. United Nations Decade of Education for Sustainable Development (DESD), 2005–2014: Review of Contexts and Structures for Education for Sustainable Development Learning for a Sustainable World; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, J.; da Silva, S.A.; Carvalho, A.S.; de Andrade Guerra, J.B.S.O. Education for Sustainable Development and Its Role in the Promotion of the Sustainable Development Goals. In Curricula for Sustainability in Higher Education; Davim, J.P., Ed.; Management and Industrial Engineering; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 1–18. ISBN 978-3-319-56505-7. [Google Scholar]

- Mogensen, F.; Schnack, K. The Action Competence Approach and the ‘New’ Discourses of Education for Sustainable Development, Competence and Quality Criteria. Environ. Educ. Res. 2010, 16, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantinescu, C. Valuing interdependence of education, trade and the environment for the achievement of sustainable development. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 116, 3340–3344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hopkins, C. Twenty Years of Education for Sustainable Development. J. Educ. Sustain. Dev. 2012, 6, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luppi, E. Training to education for sustainable development through e-learning. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 15, 3244–3251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- McIntosh, M. Creating Global Citizens and Responsible Leadership: A Special Theme Issue of The Journal of Corporate Citizenship (Issue 49); Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira, S.R. The environmental education as a path for a global sustainability. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 106, 2769–2774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). ESD—Building a Better, Fairer World for the 21st Century; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2013; Available online: http://u4614432.fsdata.se/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/esd.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Wals, A.E. Review of Contexts and Structures for Education for Sustainable Development; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Global Citizenship Education: An Emerging Perspective; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2013; Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000224115 (accessed on 25 February 2025).

- Capra, F. Sustainable living, ecological literacy, and the breath of life. Can. J. Environ. Educ. 2007, 12, 9–18. [Google Scholar]

- Piscitelli, A.; D’Uggento, A.M. Do young people really engage in sustainable behaviors in their lifestyles? Soc. Indic. Res. 2022, 163, 1467–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Education for Sustainability—From Rio to Johannesburg: Lessons Learnt from a Decade of Commitment; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Fien, J. Education for sustainable living: An international perspective on environmental education. S. Afr. Environ. Educ. 1993, 13, 7–20. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Education for Sustainable Development: Sourcebook; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization: Paris, France, 2012; Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000216383 (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Kelly, A.V. The Curriculum: Theory and Practice, 6th ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Null, W. Curriculum: From Theory to Practice, 2nd ed.; Rowman & Littlefield: Lanham, MD, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wynveen, B.J.; Meyer, A.R.; Wynveen, C.J. Promoting sustainable living among college students: Key programming components. J. For. 2019, 117, 353–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Åhlberg, M.; Aanismaa, P.; Dillon, P. Education for sustainable living: € Integrating theory, practice, design, and development. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 2005, 49, 167–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, N.; Grove, S.; Gray, J. Understanding Nursing Research: Building an Evidence-Based Practice, 5th ed.; Elsevier Saunders: St Louis, MO, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Istenic Starcic, A.; Terlevic, M.; Lin, L.; Lebenicnik, M. Designing Learning for Sustainable Development: Digital Practices as Boundary Crossers and Predictors of Sustainable Lifestyles. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, S. Learning by Sustainable Living to Improve Sustainability Literacy. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2020, 1, 161–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiek, A.; Withycombe, L.; Redman, C.L. Key competencies in sustainability: A reference framework for academic program development. Sustain. Sci. 2011, 6, 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiek, A.; Withycombe, L.; Redman, C.; Mills, S.B. Moving forward on competence in sustainability research and problem solving. Environ. Sci. Policy Sustain. Dev. 2011, 53, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, A.; Montecinos, C.; Cádiz, J.; Jorratt, P.; Manriquez, L.; Rojas, C. Working Relationally on Complex Problems: Building Capacity for Joint Agency in New Forms of Work. In Agency at Work; Goller, M., Paloniemi, S., Eds.; Professional and Practice-based Learning; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; Volume 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, L.A.; Smolen, L.A.; Oswald, R.A.; Milam, J.L. Preparing students for global citizenship in the twenty-first century: Integrating social justice through global literature. Soc. Stud. 2012, 103, 158–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, R. From education for sustainable development to ecopedagogy: Sustaining capitalism or sustaining life? Green Theor. Praxis J. Ecopedag. 2008, 4, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, C. The Psychology of Sustainable Behavior: Tips for Empowering People to Take Environmentally Positive Action; Minnesota Pollution Control Agency: Duluth, MN, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP). Fostering and Communicating Sustainable Lifestyles: Principles and Emerging Practice. 2016. Available online: https://www.unep.org/resources/report/fostering-and-communicating-sustainable-lifestyles-principles-and-emerging-0 (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Backhaus, J.; Breukers, S.; Paukovic, M.; Mourik, R.; Mont, O. Sustainable Lifestyles. Today’s Facts and Tomorrow’s Trends; D1. 1. Sustainable Lifestyles Baseline Report; Centre on Sustainable Consumption and Production: Wuppertal, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Swetha, S.; Viswanathappa, G. Assessment of Sustainable Lifestyles Practices of Student Teachers. New Trends Teach. Learn. Tech. 2024, 1, 374. [Google Scholar]

- Vukelić, N.; Rončević, N. Student Teachers’ Sustainable Behavior. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNGA. Report of the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, United Nations). 1992. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/171232/EB91_Inf.Doc-5_eng.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Schulte, J.; Hallstedt, S.I. Challenges for Integrating Sustainability in Risk Management—Current State of Research. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Engineering Design (ICED), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 21–25 August 2017; Volume 2, pp. 327–336. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, T. Motivating sustainable consumption. Sustain. Dev. Res. Netw. 2005, 29, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Garg, A.B.; Agarwal, M. Sustainable Innovations for Lifestyle, SDGs, and Greening Education. In Design for Equality and Justice; Bramwell-Dicks, A., Evans, A., Winckler, M., Petrie, H., Abdelnour-Nocera, J., Eds.; INTERACT 2024. Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 14535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagherimajd, R.; Balaghat, S.R. The impact of green university on students sustainable lifestyles. Qtly. J. Res. Plan. High. Educ. 2023, 28, 159–186. [Google Scholar]

- Agyeman, J.; Bullard, R.; Evans, B. (Eds.) Just Sustainabilities: Development in an Unequal World; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Carley, M.; Spapens, P. Sharing the World: Sustainable Living and Global Equity in the 21st Century; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2017; Available online: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/mono/10.4324/9781315087993/sharing-world-phillipe-spapens-michael-carley (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Li, P.; Wu, J. Sustainable living with risks: Meeting the challenges. Hum. Ecol. Risk. Assess. 2019, 25, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cubukcu, E. Walking for Sustainable Living. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 85, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayward, B.; Roy, J. Sustainable Living: Bridging the North-South Divide in Lifestyles and Consumption Debates. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2019, 44, 157–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munro, D.A.; Holdgate, M.W. Caring for the Earth: A Strategy for Sustainable Living; World Conservation Union (IUCN): Gland, Switzerland, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, J.G. The limits to caring: Sustainable living and the loss of biodiversity. Conserv. Biol. 1993, 7, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combes, B. The United Nations decade of education for sustainable development (2005–2014): Learning to live together sustainably. Appl. Environ. Educ. Commun. 2005, 4, 215–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akenji, L.; Chen, H. A Framework for Shaping Sustainable Lifestyles, Determinants and Strategies; UNEP: Nairobi, Kenya, 2016; Available online: https://www.oneplanetnetwork.org/sites/default/files/a_framework_for_shaping_sustainable_lifestyles_determinants_and_strategies_0.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Hendriyani, M.E.; Rafenia, V.; Maharani, S.; Al-Azis, H. The Implementation of the Independent Curriculum through Independent Project on Sustainable Lifestyle Theme for Grade 10 Students. J. Pendidik. Indones. Gemilang 2023, 3, 242–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. “What is Sustainability?”. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/sustainability#:~:text=Sustainability%20is%20based%20on%20a,indirectly%2C%20on%20our%20natural%20environment (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Whitmarsh, L.; Haggar, P.; Mitev, K.; Nash, N.; Whittle, C. Sustainable lifestyle change. In The Routledge International Handbook of Changes in Human Perceptions and Behaviors; Taku, K., Shackelford, T.K., Eds.; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Samudyatha, U.C.; Muninarayana, C.; Vishwas, S.; Prasanna, K.B.T. Engaging school children in sustainable lifestyle: Opportunities and challenges. Environ. Res. 2024, 242, 117673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterling, S. Sustainable Education: Re-Visioning Learning and Change; Schumacher Briefings: Bristol, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, V. The Ecological Footprint as an Environmental Education Tool for Knowledge, Attitude and Behaviour Changes Towards Sustainable Living. Master’s Thesis, University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez, M. Sustainability integration in industrial design education: A worldwide survey. In Connected 2007 International Conference on Design Education; University of New South Wales: Sydney, Australia, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, L.; Manion, L.; Morrison, K. Research Methods in Education, 6th ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Creswell, J.D. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches; Sage Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Fraenkel, J.R.; Wallen, N.E.; Hyun, H.H. How to Design and Evaluate Research in Education; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Koçulu, A.; Topçu, M.S. Development and Implementation of a Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) Unit: Exploration of Middle School Students’ SDG Knowledge. Sustainability 2024, 16, 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büyüköztürk, Ş. Data Analysis Handbook for Social Sciences: Statistics, Research Design, SPSS Practices and Interpretation, 22nd ed.; Pegem Academy Publishing: Ankara, Türkiye, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Yuzbasıoglu, M.K. Examining the Impact of Interdisciplinary Practices on Secondary School Students’ Awareness of Sustainable Living. Kastamonu Educ. J. 2023, 31, 590–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suna, M.; Cengelci Köse, T. The Effect of Activities for Sustainability Awareness on Students’ Sustainable Living Awareness in the Social Studies Course. TAY J. 2023, 7, 275–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayaydın, Y.; Usta Gezer, S.; Acar Sesen, B. A Study on Sustainable Living Awareness of Gifted Secondary School Students. Res. Educ. Psychol. 2023, 7, 602–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piao, X.D.; Managi, S. The international role of education in sustainable lifestyles and economic development. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 8733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berglund, T.; Gericke, N.; Rundgren, S.-N.C. The implementation of education for sustainable development in Sweden: Investigating the sustainability consciousness among upper secondary students. Res. Sci. Technol. Educ. 2014, 32, 318–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, D.; Gericke, N.; Chang Rundgren, S.N. The effect of implementation of education for sustainable development in Swedish compulsory schools—Assessing pupils’ sustainability consciousness. Environ. Educ. Res. 2016, 22, 176–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J.; Shallcross, T. Social change and education for sustainable living. Curric. Stud. 1998, 6, 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, A. Education for Sustainable Development and Global Citizenship Adult and Community Learning in Wales—From Policy to Pedagogy. Ph.D. Thesis, Swansea University, Swansea, Wales, 2018. Available online: http://cronfa.swan.ac.uk/Record/cronfa48775 (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- Guthrie, C. SDG Thinking: A Hands-on Learning Activity for the SDGs. 2023. Available online: https://ic-sd.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/2023-submission_388.pdf (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- Wynveen, B.J. Improving sustainable living education through the use of formative experiments. J. Educ. Sustain. Dev. 2017, 11, 14–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vladimirova, E. Raising Awareness Together: How Can the EU Engage with Civil Society to Promote Sustainable Lifestyles? In Istituto Affari Internazionali Working Paper; Istituto Affari Internazionali: Rome, Italy, 2012; Volume 12, pp. 2–12. [Google Scholar]

- Villanueva, X.; Villarroel, J.D.; Antón, A. Environmental Awareness and Its Relationship with the Concept of the Living Being: A Longitudinal Study. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margett-Jordan, T.; Falcon, R.G.; Witherington, D.C. The Development of Preschoolers’ Living Kinds Concept: A Longitudinal Study. Child Dev. 2017, 88, 1350–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coskun, A.; Zimmerman, J.; Erbug, C. Promoting sustainability through behavior change: A review. Des. Stud. 2015, 41, 183–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).