Balancing Objectivity and Subjectivity in Agricultural Funding: The Case of AKIS Measures

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. The Debate of Selection Criteria

2.2. Current State of the AKIS Strategy

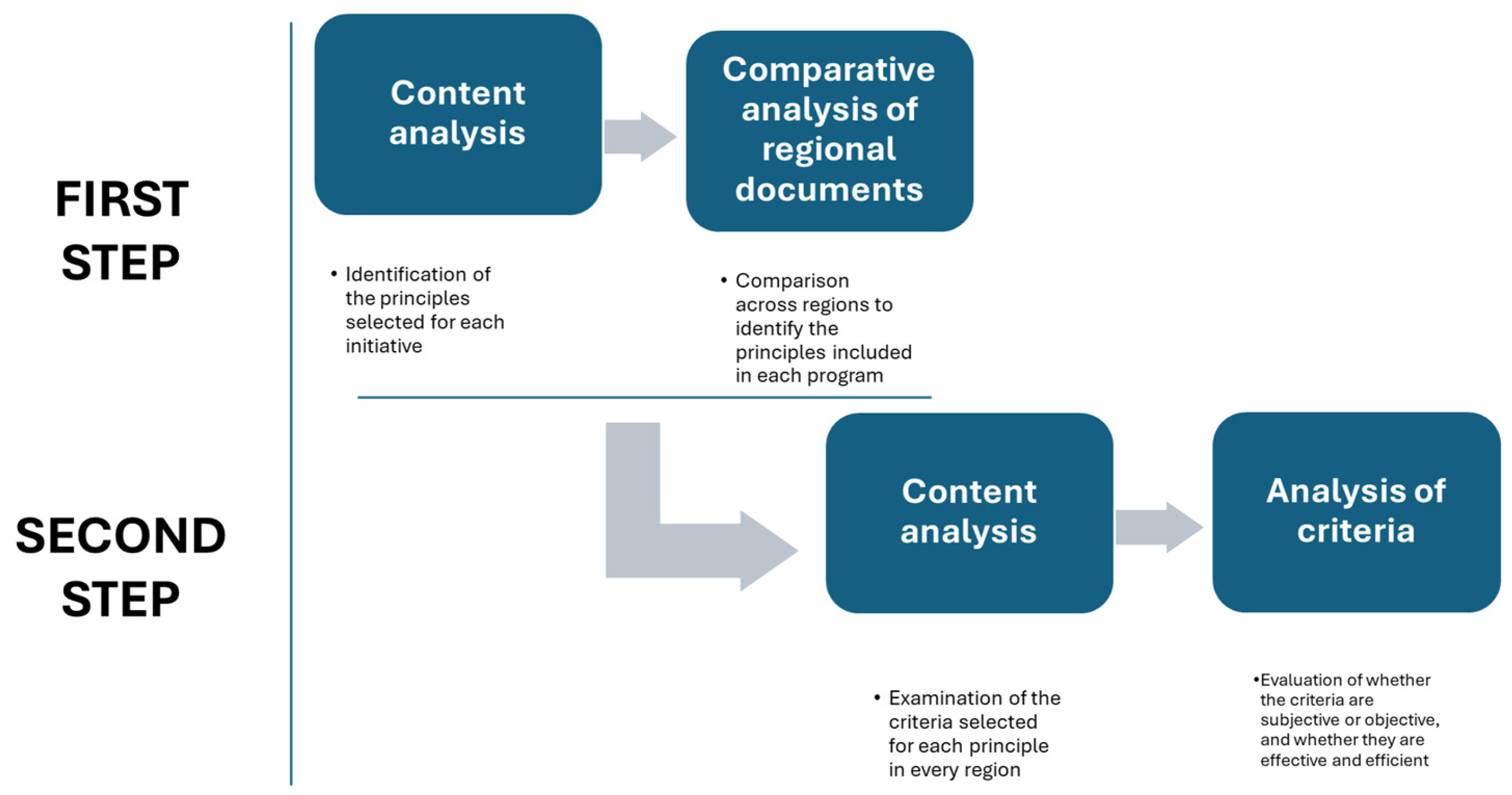

3. Methodology

4. Results

4.1. First Step

4.2. Second Step

5. Discussion

6. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AKIS | Agricultural Knowledge and Innovation System |

| CAP | Common Agricultural Policy |

Appendix A

| Selection Principles | Selection Criteria | Indicator | Region | Objective/ Subjective |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Partnership characteristics of the Operational Group in relation to the project | Involvement of a plurality of agricultural, agri-food, and forestry enterprises | Number of agricultural, agri-food, or forestry enterprises involved in the project | Abruzzo/Trento/Bolzano | Objective |

| Organizational and managerial capacity | Lead partner with administrative/accounting skills in projects funded by the FEASR funds | Trento | Objective | |

| Presence of a consultancy center/expert consultant | Trento | Subjective | ||

| Degree of diversification of sectors represented by the partners | Number of sectors represented by the partners | Bolzano | Objective | |

| Presence of one or more external experts collaborating with the GO | Bolzano | Objective | ||

| Partnership | Quality of the partnership | Veneto | Subjective | |

| Incentive for the presence of consultancy providers | Involvement of consultancy organizations | Number of consultancy organizations | Abruzzo | Objective |

| Presence of a consultancy center or an expert consultant in the specific sector of the project | Bolzano/Veneto | Objective | ||

| Consultancy provider partners | Consultancy provider identified as the lead partner | Veneto | Objective | |

| Qualitative characteristics of the project | Technical–scientific validity of the project | The project idea presents the main issue and proposed solutions in a fully adequate manner, with technical–scientific references and specificity concerning the regional context as specified in the call | Abruzzo/Bolzano | Subjective |

| Relevance of the needs and issues addressed | Trento | Subjective | ||

| Level of specialization of the technical–scientific team in relation to the innovative solution | Trento | Subjective | ||

| Degree of innovation and originality of the proposed solution | Trento/Bolzano | Subjective | ||

| Methodological adequacy | Clarity in the description of the project objectives and consistency between objectives and planned activities | Trento | Subjective | |

| Skills of human resources in relation to planned activities | Trento | Subjective | ||

| Consistency of the implementation timeline with the volume of planned activities, also in relation to the CSR timelines | Trento | Subjective | ||

| Cost analysis | Allocation within the budget of expenses, with a breakdown of actions for each partner, relevance, and appropriateness in relation to the planned activities | Trento | Subjective | |

| Clarity and completeness of the submitted estimates and comparisons | Trento | Subjective | ||

| Involvement of agricultural/forestry enterprises in proposing project themes | Conducting surveys to analyze needs | Trento | Objective | |

| Correlation between project content and Specific Objectives of Article 6 Reg. (EU) 2021/2115 | Project content related to the conservation of natural resources, climate, and biodiversity | Trento | Subjective | |

| Project content related to competitiveness, food, health, employment, and rural area development | Trento | Subjective | ||

| Impact on the agri-food and forestry sector | Bolzano | Subjective | ||

| Involvement of the agri-food/forestry supply chain | Number of stages of the supply chain involved | Bolzano | Objective | |

| Project aimed at increasing digital skills, the dissemination of digital tools, and the availability of digital services in rural areas | Bolzano | Subjective | ||

| Quality of dissemination and dissemination of results activities | Presence and quality of communication plans | Adequacy of the objectives presented in the communication plan | Trento | Subjective |

| Consistency of proposed activities with the objectives presented in the communication plan | Trento | Subjective | ||

| Types of stakeholders involved in communication and dissemination activities | Trento | Subjective | ||

| Plurality of dissemination events or activities | Number of dissemination events or activities | Bolzano | Objective | |

| Dissemination of results | Quality of dissemination and dissemination activities, particularly through the communication channels of the CAP2030 Network | Veneto | Subjective | |

| Organizational and managerial capacity of the Operational Group | Presence of an administrative lead partner | Bolzano | Objective | |

| Experience of the lead partner in projects supported by the European Union | At least one funded project | Bolzano | Objective | |

| Completeness and clarity of the budget estimate | Bolzano | Subjective | ||

| Involvement of farmers/foresters in proposing project themes (bottom-up) | Bolzano | Objective | ||

| Presence of a SWOT analysis | Bolzano | Objective | ||

| Sustainability | Environmental sustainability in the project | Bolzano | Subjective | |

| Animal welfare | Bolzano | Subjective | ||

| Social sustainability | Bolzano | Subjective |

| Selection Principles | Selection Criteria | Indicator | Region | Objective Subjective |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subjective characteristics of the partnership | Level and quality of interactions among cooperation group participants and the involvement of partners in project activities | Piemonte | Subjective | |

| Presence within the cooperation group of the various skills necessary to develop activities and transfer project results | Piemonte | Subjective | ||

| Stability of the partnership and the cooperation group’s ability to become independent from public funding | Presence of stable forms of associated management (e.g., associations/consortia) | Piemonte | Subjective | |

| Number of involved owners or number of new owners associated with existing associative forms | Piemonte | Objective | ||

| Qualitative characteristics of the project | Clear description of the objectives that the project proposal aims to achieve; consistency between objectives and planned activities; a realistic and feasible work plan, also considering the organization and coordination of activities | Piemonte | Subjective | |

| Clear and adequate project documentation in terms of completeness and compliance (with particular reference to the eligibility of expenses), consistency between the documentary part and digital submission, and proper allocation of expenses between activities and partners | Piemonte | Subjective | ||

| Proportionality between investments and results | Piemonte | Subjective | ||

| Area involved in the interventions subject to funding | Piemonte | Objective | ||

| Area covered by management contracts | Piemonte | Objective | ||

| Quality of dissemination and communication of results | Dissemination of project results in terms of quality, diversification of planned methods, appropriateness to project themes, and impact/effect | Piemonte | Subjective | |

| Only for the forestry sector: Specific themes in regional planning to ensure consistency with regional forestry programming | The ability of project objectives to address issues or create opportunities for forestry sector operators | Piemonte | Subjective | |

| Innovation content in terms of organization and subject matter | Piemonte | Subjective | ||

| Economic development effects derived from the project and the cooperation’s ability to generate long-term stable impacts | Duration of the management contract beyond the prescribed minimum | Piemonte | Objective | |

| Presence of actions for ecosystem services development | Piemonte | Objective | ||

| Sustainable forest management (SFM) and/or traceability | Number of individuals | Piemonte | Objective | |

| Quality of wood, woody fuels (ISO 17225 [25]), carbon footprint, and environmental sustainability | Presence/adoption of a certificate issued by a third party | Piemonte | Objective | |

| Presence/adoption of product quality certification resulting from the application of a specific standard | Piemonte | Objective |

| Selection Principles | Selection Criteria | Indicator | Region | Objective/ Subjective |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Project quality | Planned project activities | Number of activities | Toscana | Objective |

| Overall project consistency, clarity, and concreteness of objectives and expected results | Toscana | Subjective | ||

| Methodology for implementing the planned activities | Toscana/Abruzzo | Subjective | ||

| Completeness in describing the communication strategy | Toscana | Subjective | ||

| Structuring of the project into activities that are coherent with each other and with the project objectives | Piemonte/Veneto | Subjective | ||

| The project budget is realistic, and the ratio between the total requested resources and the planned objectives and activities appears appropriate | Piemonte/Veneto | Subjective | ||

| Completeness and level of innovation in the service offering in terms of provided support | Presence of a detailed information sheet for each type of proposed service | Campania | Objective | |

| Presence of a website with one or more sections dedicated to information and knowledge exchange | Campania | Objective | ||

| Presence of one or more social media services with a sufficient level of periodic updates | Campania | Objective | ||

| Presence of an e-learning platform to provide additional services alongside in-person activities and channels for interaction with participants | Campania | Objective | ||

| Tools for third-party monitoring of service quality | Campania | Objective | ||

| Project team quality | Complementary and targeted composition of the project partnership | Toscana/Veneto | Subjective | |

| Experience of the lead partner in coordinating cooperation projects | Toscana | Subjective | ||

| Presence of a public or private research organization as a project partner with relevant expertise in relation to the project’s objectives and activities | Toscana/Abruzzo | Objective | ||

| Presence of producer organizations, producer associations, cooperatives, consortia, or food districts as project partners with relevant expertise in relation to the project’s objectives and activities | Toscana | Objective | ||

| Presence of consultancy service providers within the partnership | Toscana/Abruzzo | Objective | ||

| Availability of the necessary competencies | Piemonte | Subjective | ||

| Presence of equipment, services, and facilities required for the implementation of planned activities | Piemonte | Subjective | ||

| Experience of qualified personnel in information activities | Campania | Objective | ||

| Qualified teaching staff | Campania | Objective | ||

| Qualification/experience of consultants | Campania | Objective | ||

| Consistency of the topics addressed with the general and specific objectives of the CAP | The project defines activities/services consistent with the objectives of the CAP 2023–2027 | Number of CAP objectives covered by the project | Toscana/Piemonte/Veneto/Abruzzo/Campania | Subjective |

| Consistency of the topics addressed with the characteristics of the territories and/or supply chains the project refers to | The project defines the consistency of the services/activities it intends to develop, with a clear reference to the territory and/or the supply chains involved and their replicability | Toscana/Piemonte/Veneto/Abruzzo/Campania | Subjective | |

| Presence of AKIS (Agricultural Knowledge and Innovation System) | Campania | Subjective | ||

| Ability to engage the target group based on the preliminary identification of specific topics and objectives | Campania | Subjective | ||

| Connection with the projects of the EIP-AGRI Operational Groups (OGs) and those of research and innovation supported by other EU, national, and regional funds | Clear, direct, and consistent connection with the project | Toscana/Abruzzo | Subjective | |

| Dissemination activities of the EIP-AGRI regional OGs or research and innovation projects funded by other EU, national, and regional funds, and/or contributing to such organizations in collaboration with them | Piemonte | Objective | ||

| Presence in the partnership of the lead partners of the OGs or research organizations responsible for research programs funded by other funds | Campania | Objective |

| Selection Principles | Selection Criteria | Indicator | Region | Objective/ Subjective |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quality of consultancy projects | Completeness and innovation of the consultancy project in terms of available support | The score is assigned based on the presence of the following cumulative support tools:

| Campania | Objective |

| Completeness and innovation of the consultancy project in terms of the consultancy offer | Campania/Abruzzo | Subjective | ||

| The project’s ability to demonstrate the alignment between the support needs expressed by potential beneficiaries and the project’s content | Piemonte | Subjective | ||

| Logistics organization of the offered service | Presence of an operational office | Abruzzo | Objective | |

| Description of the project’s objectives | Emilia Romagna | Subjective | ||

| Description and scheduling of activities | Emilia Romagna | Subjective | ||

| Description and preparation of the final report | Emilia Romagna | Subjective | ||

| Quality of the consultancy service provider | Experience of the consultants | Number of years of experience | Campania/ Piemonte/Abruzzo | Objective |

| Number of consultancies | Campania | Objective | ||

| Presence of recognized operational offices | Campania | Objective | ||

| Environmental impact | Presence of quality certifications for the consultancy provider | Campania/Piemonte | Objective | |

| Quality of the staff | Presence of university professors, staff registered in a relevant professional register, and staff with a degree or diploma in agricultural subjects with at least 3 years of documented experience in the subjects of consultancy | Abruzzo/Emilia Romagna | Objective | |

| Consistency of the proposals with the identified topics | Consistency | Emilia Romagna | Subjective | |

| Incentives for specific topics and/or objectives and/or territorial impact and/or types of actions taken to address prioritized issues | Consultancy hours for specific topics | Number of hours | Piemonte | Objective |

| Experience and training in the context of innovation and research | Curricula | Piemonte | Objective |

| Selection Principles | Selection Criteria | Indicator | Region | Objective/ Subjective |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Project quality | Quality of the training methods | Number of bibliographic references | Piemonte | Objective |

| Number of face-to-face lessons | Piemonte | Objective | ||

| Types of lessons (online, blended, in-person) | Piemonte | Objective | ||

| Quality of the project team | Experience of professors | Level of education | Piemonte | Objective |

| Final evaluation | Presence of customer satisfaction evaluation | Piemonte | Objective | |

| Level of accessibility of online content | Piemonte | Objective | ||

| Stakeholders have a certification system | Piemonte | Objective | ||

| Consistency of the topics addressed with the general and specific objectives of the CAP | Number of CAP objectives covered | Piemonte | Subjective | |

| Incentives for specific topics and/or objectives and/or territorial impact and/or types of actions | Inclusion of topics in the project | Piemonte | Subjective | |

| Connection with the projects of the EIP-AGRI Operational Groups (OGs) and/or with research and innovation projects funded by other EU, national, and regional funds | Funding or project documentation | Piemonte | Objective |

| Selection Principles | Selection Criteria | Indicator | Region | Objective/Subjective |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Project quality | Presence of expert instructors | Number of hours | Veneto/Toscana | Objective |

| Presence of degree-holding instructors | Number of hours | Veneto | Objective | |

| Training project with courses to be carried out in collaboration with the EIP-AGRI OGs benefiting from SRG01 intervention | Veneto | Objective | ||

| Training project presented by a certified training organization | Veneto/Abruzzo | Objective | ||

| Quality of educational materials and innovative tools | Campania/Toscana/Lombardia | Subjective | ||

| Presence of additional training hours beyond the minimum required in the training project | Number of hours | Campania | Objective | |

| Clarity and completeness of the proposal | Toscana/Lombardia/ Abruzzo/Emilia Romagna | Subjective | ||

| Structure of distance, blended, or in-person training | Toscana/Piemonte | Objective | ||

| Involvement of industry entities in the training project | Toscana | Objective | ||

| Consistency of the topics addressed with the general and specific objectives of the CAP | Consistency | Number of CAP objectives covered | Piemonte/Lombardia/ Abruzzo/Emilia Romagna | Subjective |

| Experience of the service provider | Number of hours | Campania | Objective | |

| Adequate experience of the teaching staff | Campania | Subjective | ||

| Incentives for specific topics/objectives and/or territorial impact | Territorial coverage | Number of provinces | Veneto/Marche | Objective |

| Adherence to the project’s themes | Marche/Toscana/Lombardia/ Abruzzo/Piemonte/Emilia Romagna | Subjective | ||

| Coaching | Marche | Objective | ||

| Courses aimed at acquiring professional knowledge and skills for young people establishing businesses under the SER01 intervention | Number of students | Marche | Objective | |

| Availability of training sites in disadvantaged areas | Number of sites | Campania | Objective |

| Selection Principles | Selection Criteria | Indicator | Region | Objective/ Subjective |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Project quality | Presence of a service charter | Veneto | Objective | |

| Completeness of documents | Veneto | Objective | ||

| Quality of the project team | Presence of certifications | Veneto/Marche | Objective | |

| Team composition | Presence in the team of a participant in seminars/workshops organized by the European CAP Network | Veneto | Objective | |

| Presence in the team of a participant in at least one training course as per T.I. | Veneto | Objective | ||

| Expertise characteristics | Level of education | Marche | Objective | |

| Incentives for specific topics and/or objectives and/or territorial impact and/or types of activities based on regional and/or local needs | Territorial distribution | Number of municipalities | Veneto | Objective |

| Territorial structure | Number of operational offices | Veneto | Objective | |

| Adherence to the project’s themes | Marche | Subjective | ||

| Impact of costs for activities outside the region and events | Percentage of contribution allocated to activities outside the region and events | Marche | Objective |

| Selection Principles | Selection Criteria | Indicator | Region | Objective/Subjective |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Project quality | Completeness of the activities | Number of types of demonstration activities planned | Veneto | Objective |

| Number of types of demonstration activities planned | Veneto | Objective | ||

| Location of the demonstration activities | Number of activities carried out at private agricultural businesses | Veneto | Objective | |

| Ability of the project proposal to engage a high number of operators | Number of operators involved | Piemonte | Objective | |

| Budget consistency | Piemonte | Subjective | ||

| Suitability of proposed equipment | Piemonte | Subjective | ||

| Quality of the project team | Presence of beneficiary certifications | Veneto/Piemonte | Objective | |

| Team qualification | Veneto | Objective | ||

| Type of beneficiary | Level of education | Veneto | Objective | |

| Evaluation of experience gained in demonstration, experimental, and/or dissemination activities | Piemonte | Subjective | ||

| Level of online accessibility | Piemonte | Subjective | ||

| Consistency of the topics addressed with the general and specific objectives of the CAP | Consistency | Number of CAP objectives covered | Piemonte | Subjective |

| Inclusion of topics in the project | Veneto | Subjective | ||

| Incentives for specific topics | Execution method of demonstration actions | Veneto | Objective | |

| Territorial distribution | Number of municipalities | Veneto | Objective | |

| Inclusion of specific topics | Piemonte | Objective |

| Selection Principles | Selection Criteria | Indicator | Region | Objective/Subjective |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Project quality | Quality of the drafted budget | Piemonte | Subjective | |

| Quality of the drafted proposal | Piemonte/ Sicilia | Subjective | ||

| Quality of the project team | Level of equipment provided | Piemonte | Subjective | |

| Technical characteristics of the research team | Piemonte | Subjective | ||

| Consistency of the topics addressed with the general and specific objectives of the CAP | Consistency | Piemonte/ Sicilia | Objective | |

| Inclusion of topics in the project | Piemonte | Objective |

References

- Webb, R.; Buratini, J. Global challenges for the 21st century: The role and strategy of the agri-food sector. Anim. Reprod. 2016, 13, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knierim, A.; Kernecker, M.; Erdle, K.; Kraus, T.; Borges, F.; Wurbs, A. Smart farming technology innovations—Insights and reflections from the German Smart-AKIS hub. NJAS-Wagening. J. Life Sci. 2019, 90–91, 100314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lidder, P.; Cattaneo, A.; Chaya, M. Innovation and technology for achieving resilient and inclusive rural transformation. Glob. Food Sec. 2025, 44, 100827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klerkx, L.; Rose, D. Dealing with the game-changing technologies of Agriculture 4.0: How do we manage diversity and responsibility in food system transition pathways? Glob. Food Sec. 2020, 24, 100347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, G.S.; Reddy, M.; Krishna, C.; Joshi, A. Environmental Sustainability in the Digital Age: The Role of Smart Technologies in Agriculture, Urban Development, and Energy Management. Int. J. Environ. Clim. Change 2025, 15, 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labarthe, P.; Beck, M. CAP and Advisory Services: From Farm Advisory Systems to Innovation Support. EuroChoices 2022, 21, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristiano, S.; Carta, V.; Sturla, A.; D’Oronzio, M.A.; Proietti, P. AKIS and Advisory Services in Italy—Report for the AKIS Inventory (Task 1.2) of the i2connect Project; CREA: Rome, Italy, 2020; pp. 1–82. [Google Scholar]

- Sida, T.S.; Gameda, S.; Chamberlin, J.; Andersson, J.A.; Getnet, M.; Woltering, L.; Craufurd, P. Failure to scale in digital agronomy: An analysis of site-specific nutrient management decision-support tools in developing countries. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 212, 108060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anithakumari, P.; Indhuja, S.; Shareefa, M. Community farm school approach for coconut seedlings/juveniles through collaborative social actions. J. Plant. Crop. 2023, 51, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermans, F.; Klerkx, L.; Roep, D. Structural Conditions for Collaboration and Learning in Innovation Networks: Using an Innovation System Performance Lens to Analyse Agricultural Knowledge Systems. J. Agric. Educ. Ext. 2015, 21, 35–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scriven, M. The Logic of Evaluation. 2007, pp. 1–16. Available online: https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1390&context=ossaarchive (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Hug, S.E.; Aeschbach, M. Criteria for assessing grant applications: A systematic review. Palgrave Commun. 2020, 6, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinkenburg, C.J.; Ossenkop, C.; Schiffbaenker, H. Selling science: Optimizing the research funding evaluation and decision process. Equal. Divers. Incl. 2021, 41, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tailbot, K. Objective well-being indicators and subjective well-being measures: How important are they in current public policy? Encuentros Multidiscip. 2020, 64, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Veenhoven, R. Why social policy needs subjective indicators. Soc. Indic. Res. 2002, 58, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fieldsend, A.F. Agricultural knowledge and innovation systems in European Union policy discourse: Quo vadis? Stud. Agric. Econ. 2020, 122, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eidt, C.M.; Pant, L.P.; Hickey, G.M. Platform, participation, and power: How dominant and minority stakeholders shape agricultural innovation. Sustainability 2020, 12, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faure, G.; Rebuffel, P.; Violas, D. Systemic evaluation of advisory services to family farms in West Africa. J. Agric. Educ. Ext. 2011, 17, 325–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingram, J.; Mills, J. Are advisory services ‘fit for purpose’ to support sustainable soil management? An assessment of advice in Europe. Soil Use Manag. 2019, 35, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amerani, E.; Nastis, A.S.; Loizou, E.; Michailidis, A. Cross-Analysis of Agricultural Knowledge and Innovation System of Actors’ Interactions in Greece. J. Agric. Ext. 2024, 28, 9–23. [Google Scholar]

- Conway, S.F.; Farrell, M.; Weir, L. All for One and One for All: Dissecting PREMIERE’s Inclusive AKIS Stakeholder Engagement Strategy. Open Res. Eur. 2024, 4, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Rural Network. AKIS Interventions in the CAP Strategic Plan 2023–2027. 2023. Available online: https://www.reterurale.it/flex/cm/pages/ServeBLOB.php/L/IT/IDPagina/24823 (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- Duriau, V.J.; Reger, R.K.; Pfarrer, M.D. A Content Analysis of the Content Analysis Literature in Organization Studies. Organ. Res. Methods 2007, 10, 5–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, R.; Fankhauser, S.; Hamilton, K. Adaptation investments: A resource allocation framework. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Change 2010, 15, 843–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 17225; Solid Biofuels—Fuel Specifications and Classes. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014.

| COD | Principles |

|---|---|

| SRG01 | 01—Partnership characteristics of the Operational Group (GO) in relation to the project |

| 02—Reward for the presence of consulting service providers | |

| 03—Qualitative characteristics of the project | |

| 04—Quality of dissemination and communication activities of the results | |

| 05—Organizational and managerial capacity of the operational group | |

| 05.1—Reward for specific themes and/or objectives and/or territorial impact and/or types of actions activated | |

| 06—Sustainability | |

| SRG08 | 01—Subjective characteristics of the partnership |

| 02—Qualitative characteristics of the project | |

| 03—Quality of dissemination and communication activities of the results | |

| 03.1—Characteristics of those accessing the consulting service | |

| 04—Only for the forestry sector: specific themes in regional programming to ensure coherence with regional forestry programming | |

| 04.1—Alignment with intervention priorities (OS) to be used in the calls | |

| 05—Impact of the project in terms of stages of the supply chain involved (processing, conservation, storage, packaging, transformation, trade) | |

| SRG09 | 01—Quality of the project |

| 02—Quality of the project team | |

| 03—Consistency of the themes addressed with the general and specific objectives of the CAP | |

| 04—Consistency of the themes addressed with the characteristics of the territories and/or supply chains to which the project refers | |

| 05—Connection with the PEI GO projects and with research and innovation projects supported by other EU, national, and regional funds | |

| SRH01 | 01—Quality of the consultancy projects |

| 02—Quality of the consultancy provider | |

| 03—Reward for specific themes | |

| 03.1—Evaluation of the consultancy recipients | |

| 03.2—Consistency of the proposals with the identified themes | |

| 03.3—Consistency of the themes addressed with the characteristics of the territories and/or supply chains to ensure adequate consultancy | |

| 03.4—Reward for specific themes and/or objectives and/or territorial impact and/or types of actions activated to address priority issues | |

| 03.5—Characteristics of the consultancy recipients | |

| R/03—Characteristics of the consultancy service recipients | |

| P03—Reward based on the recipient | |

| P04—Reward based on the consultancy theme to ensure more targeted consultancy | |

| SRH02 | 01—Quality of the project |

| 02—Quality of the project team | |

| 03—Consistency of the themes addressed with the general and specific objectives of the CAP | |

| 04—Reward for specific themes and/or objectives and/or territorial impact and/or types of actions activated | |

| 05—Connection with PEI GO projects and/or with research and innovation projects supported by other EU, national, and regional funds | |

| SRH03 | 01—Quality of the training project |

| 02—Consistency of the themes addressed with the general and specific objectives of the CAP | |

| 03—Reward for specific themes/objectives and/or territorial impact | |

| 04—Characteristics of the training recipients in accordance with regional criteria for identifying rewards (localization, structural, managerial targets) | |

| 04.1—Characteristics of final recipients | |

| 04.2—Quality of the project team | |

| 04.2—Quality of the instructors | |

| 04.3—Quality of the training team | |

| 04.4—Characteristics of final recipients | |

| 04.5—Reward for territorial impact | |

| 05—Quality of the training provider in accordance with regional criteria for identifying rewards (e.g., previous sector experience, quality certification, etc.) | |

| 05.1—Reward based on the recipient and the theme of the training | |

| 05.2—Only for the agricultural sector | |

| 05.3—Costs/benefits of the proposal | |

| 06—Localization of the final recipients | |

| SRH04 | 01—Quality of the project |

| 02—Quality of the project team | |

| 03—Consistency of the themes addressed with the general and specific objectives of the CAP | |

| 04—Reward for specific themes and/or objectives and/or territorial impact and/or types of activities based on regional and/or local needs | |

| SRH05 | 01—Quality of the project |

| 02—Quality of the project team | |

| 03—Consistency of the themes addressed with the general and specific objectives of the CAP | |

| 04—Reward for specific themes and/or objectives and/or territorial impact and/or types of actions activated | |

| 05—Only for the agricultural sector | |

| SRH 06 | 01—Quality of the project and/or type of activity |

| 02—Quality of the project team | |

| 03—Consistency of the themes addressed with the general and specific objectives of the CAP | |

| 04—Reward for specific themes/objectives and/or territorial impact and/or type of activity | |

| 05—Characteristics of back-office service recipients (regional criteria for identifying rewards, such as localization, structural, and managerial targets) | |

| 06—Quality of the back-office service provider (regional criteria for identifying rewards, such as previous sector experience, quality certification, etc.) |

| COD | Principles | VALLE D’AOSTA | PIEMONTE | LIGURIA | LOMBARDIA | P.A. BOLZANO | P.A TRENTO | VENETO | F.V. GIULIA | EMILIA ROMAGNA | TOSCANA | UMBRIA | MARCHE | LAZIO | ABRUZZO | MOLISE | CAMPANIA | PUGLIA | BASILICATA | CALABRIA | SICILIA | SARDEGNA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SRG01 | 01 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 02 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| 03 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| 04 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| 05 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 05.1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 06 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| SRG08 | 01 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 02 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| 03 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| 03.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 04 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 04.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 05 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| SRG09 | 01 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 02 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| 03 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| 04 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| 05 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| SRH01 | 01 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 02 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| 03 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| 03.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 03.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 03.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 03.4 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 03.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| R/03 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| P03 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| P04 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| SRH02 | 01 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 02 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| 03 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| 04 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| 05 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| SRH03 | 01 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 02 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| 03 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| 04 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 04.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 04.2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 04.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 04.4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 04.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 04.6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 05 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 05.1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 05.2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 05.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 06 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| SRH04 | 01 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 02 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| 03 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| 04 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| SRH05 | 01 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 02 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| 03 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| 04 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| 05 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| SRH06 | 01 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 02 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| 03 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| 04 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| 05 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 06 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| AKIS Initiative | Total Criteria | % Objective Indicators | % Subjective Indicators | Region | For More Details, See |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SRG01—EIP AGRI Operational Groups | 27 | 38.89% | 61.11% | Abruzzo Trento Bolzano Veneto | Table A1 in Appendix A |

| SRG08—Support to pilot actions and testing of innovations | 17 | 47.06% | 52.94% | Piemonte | Table A2 in Appendix A |

| SRG09—Innovation support services Art. 78 | 24 | 50% | 50% | Toscana Piemonte Veneto Abruzzo Campania | Table A3 in Appendix A |

| SRH01—Advisory services | 14 | 60% | 40% | Campania Piemonte Abruzzo Emilia Romagna | Table A4 in Appendix A |

| SRH02—Training for advisors | 5 | 80% | 20% | Piemonte | Table A5 in Appendix A |

| SRH03—Training for farmers and other rural actors (private and public) | 17 | 70.59% | 29.41% | Veneto Marche Campania Toscana Lombardia Abruzzo Piemonte Emilia Romagna | Table A6 in Appendix A |

| SRH04—Information actions | 9 | 90% | 10% | Veneto Marche | Table A7 in Appendix A |

| SRH05—Demonstration actions for agricultural and forestry sectors and for rural areas | 15 | 62.5% | 37.5% | Veneto Piemonte | Table A8 in Appendix A |

| SRH06—Back-office services for the AKIS | 6 | 33.33% | 66.67% | Veneto Toscana Piemonte Sicilia | Table A9 in Appendix A |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

di Santo, N.; Sisto, R.; Dragone, V.; Fucilli, V. Balancing Objectivity and Subjectivity in Agricultural Funding: The Case of AKIS Measures. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4730. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104730

di Santo N, Sisto R, Dragone V, Fucilli V. Balancing Objectivity and Subjectivity in Agricultural Funding: The Case of AKIS Measures. Sustainability. 2025; 17(10):4730. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104730

Chicago/Turabian Styledi Santo, Naomi, Roberta Sisto, Vittoria Dragone, and Vincenzo Fucilli. 2025. "Balancing Objectivity and Subjectivity in Agricultural Funding: The Case of AKIS Measures" Sustainability 17, no. 10: 4730. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104730

APA Styledi Santo, N., Sisto, R., Dragone, V., & Fucilli, V. (2025). Balancing Objectivity and Subjectivity in Agricultural Funding: The Case of AKIS Measures. Sustainability, 17(10), 4730. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104730