How Do Chinese Migrant Workers Avoid Leisure-Time Physical Inactivity?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. What Are the Determinants of LTPI?

2.2. What Constraints Might LTPI Impose on Migrant Workers?

3. Case Study and Methodology

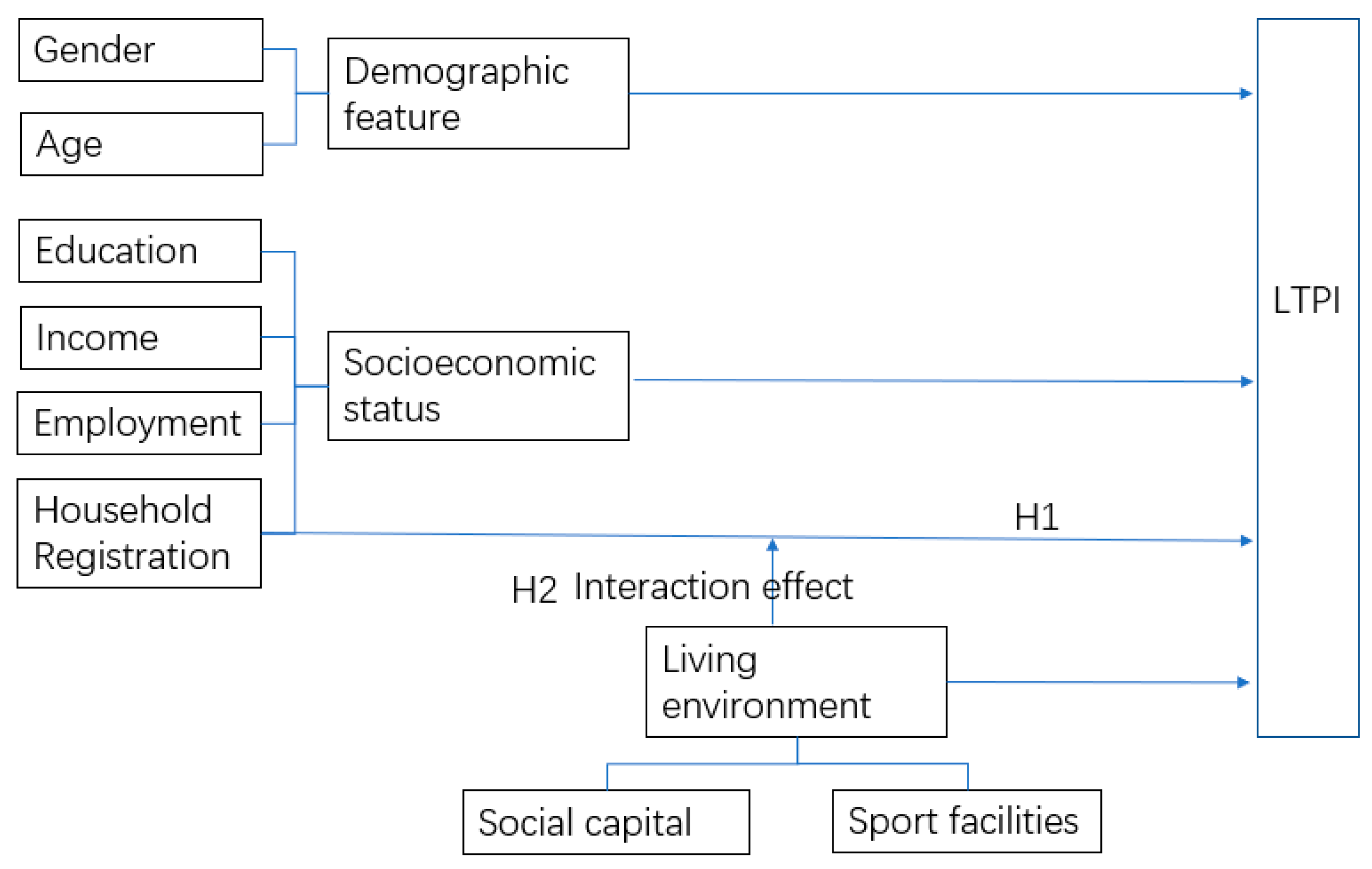

3.1. Theoretical Framework

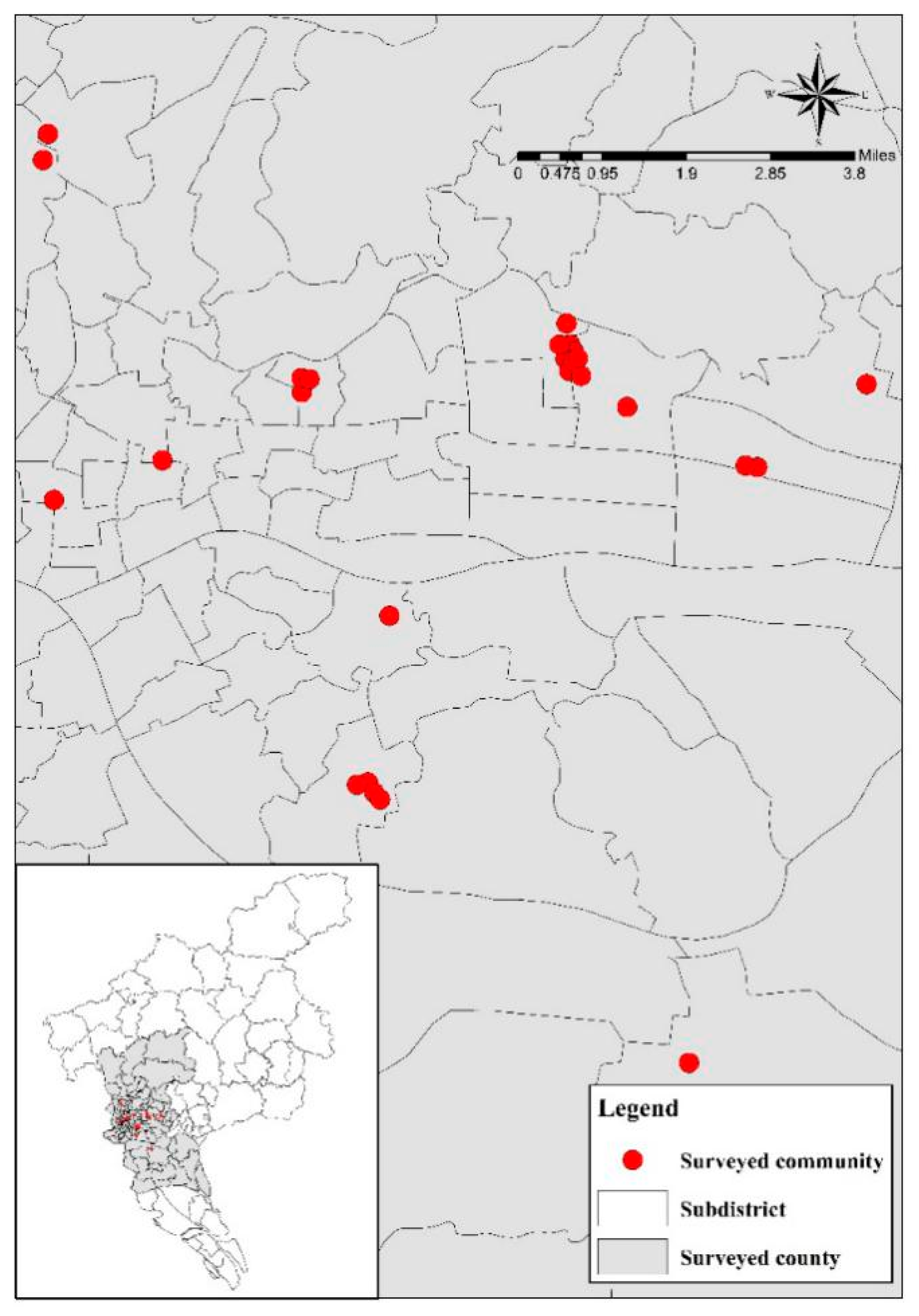

3.2. Study Area and Data

3.3. Variables and Models

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Analysis

4.2. Does Household Registration Disparity with LTPI Exist Among Residents?

4.3. What Is the Interaction Effect of Household Registration on LTPI?

4.4. Do the Determinants of LTPI Among Migrant Workers Differ?

5. Conclusions and Discussion

5.1. Conclusions

- (1)

- Although inclusive cities have been emphasized and progress has been achieved, household registration was still identified as influencing LTPI among residents. It affected LTPI through interaction with living environmental factors, such as the number of sports facilities and the number of people greeted in the community.

- (2)

- Migrant workers were more likely to have significantly higher LTPI levels than other groups. However, this constraint can be mitigated by increasing the number of sports facilities and the number of people they can greet in the community.

- (3)

- The main obstacles preventing migrant workers from engaging in leisure-time physical activity were a lack of education, social capital, and neighborhood green open spaces.

5.2. Discussion

- (1)

- The impact of household registration on migrant workers remains significant

- (2)

- Measures to help migrant workers to be leisure-time physically active

5.3. Prospects and Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bi, Y.; Wang, L.; Xu, Y.; Jiang, Y.; He, J.; Zhang, M.; Zhou, M.; Li, Y.; Xu, M.; Lu, J.; et al. Diabetes-related metabolic risk factors in internal migrant workers in China: A national surveillance study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2016, 4, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, S.; Hao, P.; Feng, J. Consumer behavior of rural migrant workers in urban China. Cities 2020, 106, 102856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, L.; Wong, F.K.W.; Hui, E.C.M. Residential satisfaction of migrant workers in China: A case study of Shenzhen. Habitat. Int. 2014, 42, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peilin Li, W.L. Economic Status and Social Attitudes of Migrant Workers in China. China World Econ. 2007, 15, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Li, W.; He, J.; Wu, L.; Yan, Z.; Tang, W. Mental health, duration of unemployment, and coping strategy: A cross-sectional study of unemployed migrant workers in eastern china during the economic crisis. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gan, X.; Zuo, J.; Ye, K.; Li, D.; Chang, R.; Zillante, G. Are migrant workers satisfied with public rental housing? A study in Chongqing, China. Habitat. Int. 2016, 56, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S. China’s Migrant Workers’ Social Security. Chin. J. Popul. Resour. Environ. 2010, 8, 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, B.; Feng, C. Commuting Pattern and Spatial Relation between Residence and Employment of Migrant Workers in Metropolitan Areas: The Case of Beijing. Urban. Plan. Forum 2012, 20, 59–64. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, B.; Feng, C.; Shen, B. Characteristics of Intra-urban Migration of Rural Migrant Workers in Beijing. Urban. Stud. 2012, 19, 72–76. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, Y.; Chang, W.; Zhou, H.; Hu, H.; Liang, W. Factors associated with health-seeking behavior among migrant workers in Beijing, China. Health Serv. Res. 2010, 10, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Miao, S.Y.; Sarkar, C.; Geng, H.Z.; Lu, Y. Exploring the Impacts of Housing Condition on Migrants’ Mental Health in Nanxiang, Shanghai: A Structural Equation Modelling Approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The National Bureau of Statistics. The 7th National Census Bulletin. Available online: http://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/zxfb/202302/t20230203_1901087.html (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Yue, Z.; Li, W.; Yan, L. Social Integration of Rural-Urban Migrants and Social Management: A Three Sectors Perspective including Government, Market, and Civil Society. J. Public. Manag. 2012, 9, 111–121. [Google Scholar]

- Guthold, R.; Ono, T.; Strong, K.L.; Chatterji, S.; Morabia, A. Worldwide variability in physical inactivity a 51-country survey. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2008, 34, 486–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, H.; Li, S. The effects of household registration system discrimination on urban–rural income inequality in China. Econ. Res. J. 2013, 48, 43–55. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.M.; Liu, Z.L. Neighborhood environments and inclusive cities: An empirical study of local residents? attitudes toward migrant social integration in Beijing, China. Landsc. Urban. Plan. 2022, 226, 104495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y. Trends and Policies of “Floating Population” in the Context of Healthy Urbanization. Econ. Geogr. 2012, 32, 25–31+43. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.; Lv, G. Research on the Subjective Welfare Effect of Population Mobility in the Process of Urbanization. Stat. Res. 2020, 37, 115–128. [Google Scholar]

- Caspersen, C.J.; Powell, K.E.; Christenson, G.M. Physical Activity, Exercise, and Physical Fitness: Definitions and Distinctions for Health-Related Research. Public Health Rep. 1985, 100, 126–131. [Google Scholar]

- Droomers, M.; Schrijvers, C.T.M.; van de Mheen, H.; Mackenbach, J.P. Educational differences in leisure-time physical inactivity: A descriptive and explanatory study. Soc. Sci. Med. 1998, 47, 1665–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, S.V.; Barbosa, A.R.; Araujo, T.M. Leisure-Time Physical Inactivity among Healthcare Workers. Int. J. Occup. Med. Env. 2018, 31, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.Z.; Stodolska, M. Leisure as a Constraint and a Manifesto for Empowerment: The Life Story of a Chinese Female Migrant Worker. Leis. Sci. 2018, 44, 121–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnsen, N.F.; Toftager, M.; Melkevik, O.; Holstein, B.E.; Rasmussen, M. Trends in social inequality in physical inactivity among Danish adolescents 1991–2014. SSM Popul. Health 2017, 3, 534–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oshio, T.; Tsutsumi, A.; Inoue, A. The association between job stress and leisure-time physical inactivity adjusted for individual attributes: Evidence from a Japanese occupational cohort survey. Scand. J. Work. Environ. Health 2016, 42, 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wu, J. Investigation on Current Condition of Migrate Worker Participating in Leisure Sports in Beijing. China Sport. Sci. Technol. 2009, 45, 133–138. [Google Scholar]

- Lindström, M.; Sundquist, J. Immigration and Leisure-Time Physical Inactivity: A population-based study. Ethn. Health 2010, 6, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Xie, H.; Zhang, Q.; Zhu, H.; Dai, X. An Investigation on Health Condition and Sports Behavior of Peasant Workers in Pearl River Delta. China Sport. Sci. 2010, 30, 11–21. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Cai, X. A review of researches on peasant worker sports in China. J. Phys. Educ. 2015, 22, 48–53. [Google Scholar]

- Salazar, M.A.; Hu, X.J. Health and lifestyle changes among migrant workers in China: Implications for the healthy migrant effect. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2016, 4, 89–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Tuyckom, C.; Van de Velde, S.; Bracke, P. Does country-context matter? A cross-national analysis of gender and leisure time physical inactivity in Europe. Eur. J. Public Health 2012, 23, 452–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trost, S.G.; Pate, R.R.; Sallis, J.F.; Freedson, P.S.; Taylor, W.C.; Dowda, M.; Sirard, J. Age and gender differences in objectively measured physical activity in youth. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2002, 34, 350–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hull, E.E.; Rofey, D.L.; Robertson, R.J.; Nagle, E.F.; Aaron, D.J. Influence of Marriage and Parenthood on Physical Activity: A 2-Year Prospective Analysis. J. Phys. Act. Health 2010, 7, 577–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalo-Almorox, E.; Urbanos-Garrido, R.M. Decomposing socio-economic inequalities in leisure-time physical inactivity: The case of Spanish children. Int. J. Equity Health 2016, 15, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- do Nascimento, T.S.; Mussi, F.C.; Palmeira, C.S.; Santos, C.A.T.; Santos, M.A. Factors related to leisure-time physical inactivity in obese women. Acta Paul. Enferm. 2017, 30, 308–315. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, P.; Grady, S.C.; Chen, G. How the built environment affects change in older people’s physical activity: A mixed- methods approach using longitudinal health survey data in urban China. Soc. Sci. Med. 2017, 192, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, A.; McMunn, A.; Banks, J.; Steptoe, A. Loneliness, social isolation, and behavioral and biological health indicators in older adults. Health Psychol. 2011, 30, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farrell, L.; Shields, M.A. Investigating the economic and demographic determinants of sporting participation in England. J. R. Stat. Soc. 2002, 165, 335–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prochaska, J.D.; Buschmann, R.N.; Jupiter, D.; Mutambudzi, M.; Peek, M.K. Subjective neighborhood assessment and physical inactivity: An examination of neighborhood-level variance. Prev. Med. 2018, 111, 336–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, A.C.; Castro, C.; Wilcox, S.; Eyler, A.A.; Sallis, J.F.; Brownson, R.C. Personal and environmental factors associated with physical inactivity among different racial-ethnic groups of U.S. middle-aged and older-aged women. Health Psychol. Off. J. Div. Health Psychol. Am. Psychol. Assoc. 2000, 19, 354–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, M.; Tan, Y.Y.; Liu, Q.M.; Ren, Y.J.; Kawachi, I.; Li, L.M.; Lv, J. Association between perceived urban built environment attributes and leisure-time physical activity among adults in Hangzhou, China. Prev. Med. 2014, 66, 60–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, L.; Sarmiento, O.; Parra, D.; Schmid, T.; Pratt, M.; Jacoby, E.; Neiman, A.; Cervero, R.; Mosquera, J.; Rutt, C. Characteristics of the built environment associated with leisure-time physical activity among adults in Bogotá, Colombia: A multilevel study. J. Phys. Act. Health 2010, 7 (Suppl. 2), 196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koohsari, M.J.; Badland, H.; Giles-Corti, B. (Re)Designing the built environment to support physical activity: Bringing public health back into urban design and planning. Cities 2013, 35, 294–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chau, C.K.; Ng, W.Y.; Leung, T.M. A review on the effects of physical built environment attributes on enhancing walking and cycling activity levels within residential neighborhoods. Cities 2016, 50, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veitch, J.; Ball, K.; Crawford, D.; Abbott, G.; Salmon, J. Is park visitation associated with leisure-time and transportation physical activity? Prev. Med. 2013, 57, 732–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crespo, C.J.; Smit, E.; Andersen, R.E.; Carter-Pokras, O.; Ainsworth, B.E. Race/ethnicity, social class and their relation to physical inactivity during leisure time: Results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1994. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2000, 18, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, Z.; Liu, F.; Zhao, Y. Happy city for everyone: Generational differences in rural migrant workers’ leisure in urban China. Urban. Stud. 2023, 60, 3252–3271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, P.; Berryman, D.L. The relationship among self-esteem, acculturation, and recreation participation of recently arrived Chinese immigrant adolescents. J. Leis. Res. 1996, 28, 251–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, M.; Peng, Y. A comparative study of urban integration of floating population: Taking six cities in china’s eastern coastal region as an example. City Plan. Rev. 2014, 38, 9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, R.; Ding, B. Social Integration, Relative Deprivation, and Sense of Gain of Floating population. Soc. Constr. 2019, 6, 16–29. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, X.; Pan, J.; Liu, G.G. Does participating in health insurance benefit the migrant workers in China? An empirical investigation. China Econ. Rev. 2014, 30, 263–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, F.; Ma, L.; Pang, L.; Zhao, X.; Pan, Y. Vulnerability of migrant workers’ livelihoods in Hangzhou City and the countermeasures. Prog. Geogr. 2013, 32, 389–399. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, S.; Xu, J. The Effects of Social Medical Insurance Participation on Migrant Workers in China: Estimation Based on the Propensity Score Matching Approach. Iran. J. Public. Health 2016, 45, 1513–1514. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zheng, S.; Song, Z.; Sun, W. Do affordable housing programs facilitate migrants’ social integration in Chinese cities? Cities 2020, 96, 102449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Wang, H. Do neighbourhoods have effects on wages? A study of migrant workers in urban China. Habitat. Int. 2013, 38, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Yu, Y. Some Issues on the Crime of Migrant Workers. J. Railw. Police Coll. 2008, 18, 86–91. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B.; Li, X.; Stanton, B.; Fang, X. The influence of social stigma and discriminatory experience on psychological distress and quality of life among rural-to-urban migrants in China. Soc. Sci. Med. 2010, 71, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Zhou, C.; Jin, W. Integration of migrant workers: Differentiation among three rural migrant enclaves in Shenzhen. Cities 2020, 96, 102453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Chen, L.; Tan, J. Research on the Influencing Factor for the Housing Satisfaction of Migrant Workers:an Empirical Analysis from Guangzhou. Eng. Econ. 2017, 27, 46–50. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, B.; Chai, Y.; Tan, Y. Research on Daily Activity Spaces of Residents in Xining City Based on Comparison of Residential Areas. Areal Res. Dev. 2017, 36, 152–158. [Google Scholar]

- Storgaard, R.L.; Hansen, H.S.; Aadahl, M.; Glumer, C. Association between neighbourhood green space and sedentary leisure time in a Danish population. Scand. J. Public Health 2013, 41, 846–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez-Almendros, S.; Benítez-Parejo, N.; Gonzalez-Ramirez, A.R. Logistic regression models. Allergol. Et. Immunopathol. 2011, 39, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asferg, C.; Mogelvang, R.; Flyvbjerg, A.; Frystyk, J.; Jensen, J.S.; Marott, J.L.; Appleyard, M.; Schnohr, P.; Jensen, G.B.; Jeppesen, J. Interaction between leptin and leisure-time physical activity and development of hypertension. Blood Press. 2011, 20, 362–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, D.F.K.; Leung, G. The functions of social support in the mental health of male and female migrant workers in China. Health Soc. Work. 2008, 33, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- General Office of the National Health and Family Planning Commission. Action Plan for Health Education and Promotion among Floating Population (2016–2020); The National Health and Family Planning Commission: Beijing, China, 2016.

- Man, J.; Yang, J. Research on the Influence of Urban Sports Public Service on the Social Integration of Migrant Population. J. Xi’an Phys. Educ. Univ. 2022, 39, 301–310. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.-J.; Yeo, I.-S.; Ahn, B.-W. A Study of Social Integration through Sports Program among Migrant Women in Korea. Societies 2021, 11, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Feature | Variable | Description | Assignment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | X1 Gender | Gender | Male = 1; Female = 2 |

| X2 Age | In accordance with regulations issued by both China and the World Health Organization, a new age bracket is proposed. The age brackets include adolescents aged 18–28, mature youth aged 29–44, and middle-aged persons aged 45–59. Aged means elderly persons aged 60 years and above. | Adolescent youth = 1; Mature youth = 2; Middle-aged persons = 3; Aged = 4 | |

| Socioeconomic status | X3 Household registration | Household registration category | Local urban residents = 1; Local rural residents = 2; migrant urban residents = 3; migrant workers = 4 |

| X4 Marital status | Current marital status | Unmarried = 1; Married = 2 | |

| X5 Education | Lower education refers to those who were awarded no degree or who had a primary school or junior high school education; secondary education refers to those who attended senior high school, technical secondary school and junior college; higher education includes undergraduates and graduates. | Lower education level = 1; secondary education level = 2; higher education level = 3 | |

| X6 Employment | Three employed states were specified as follows: Full-time, temporary, and unemployed. | Full-time = 1; Temporary work = 2; Unemployed = 3 | |

| X7 Income | According to the CGMBS *, the mean monthly income of individuals was divided into four levels: Low income (less than 3000 RMB); medium income (3000–4999 RMB); medium and high income (5000–6999 RMB); high income (≥7000 RMB). | Low income = 1; Medium income = 2; Medium and high income = 3; High income = 4 | |

| Green open space in the community | X8 Dis. | The distance between the residential community and the nearest park or square outside the community (unit: m) | Continuous variable |

| X9 GRW | The proportion of green area in the community zone | Continuous variable | |

| X10 TGR | The proportion of green area within the community and within a one-kilometer radius outside the community boundary. | Continuous variable | |

| X11 SFI | The number of sport facilities in the community. | Continuous variable | |

| X12 SFO | The number of sport facilities within a one-kilometer radius outside the community boundary. | Continuous variable | |

| Social network | X13 RFI | The number of relatives and friends who live in the same community (including relatives or friends who live together). | Less than 5 = 1; 6–10 = 2; 11–20 = 3; 21–30 = 4; More than 30 = 5 |

| X14 PGI | The number of residents (adults) who greet each other when meeting in the community, except their relatives | Less than 10 = 1; 10–20 = 2; 21–30 = 3; 31–50 = 4; More than 50 = 5 |

| Local Urban Residents | Local Rural Residents | Migrant Urban Residents | Migrant Workers | Sum | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Y LTPI | 0 | 606 | 25 | 105 | 52 | 788 |

| 1 | 159 | 6 | 27 | 44 | 236 | |

| Sum | 765 | 31 | 132 | 96 | 1024 |

| Local Urban Residents | Local Rural Residents | Migrant Urban Residents | Migrant Workers | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| X1 Gender | 1.453 | 1.333 | 1.704 | 1.386 |

| X2 Age | 2.145 | 1.667 | 2.037 | 1.568 |

| X4 Marital status | 1.698 | 1.333 | 1.704 | 1.432 |

| X5 Education | 2.113 | 1.833 | 2.037 | 1.750 |

| X6 Employment | 1.214 | 1.000 | 1.111 | 1.159 |

| X7 Income | 2.673 | 2.333 | 2.852 | 2.727 |

| X8 Dis. | 614.767 | 807.000 | 628.593 | 527.795 |

| X9 GRW | 282 | 0.308 | 0.272 | 0.260 |

| X10 TGR | 0.162 | 0.205 | 0.173 | 0.190 |

| X11 SFI | 2.918 | 2.333 | 3.074 | 2.568 |

| X12 SFO | 16.899 | 17.500 | 14.963 | 16.364 |

| X13 RFI | 1.509 | 2.833 | 1.556 | 1.159 |

| X14 PGI | 1.956 | 3.000 | 1.630 | 1.386 |

| Variable | B | Wals | Sig. | Exp(B) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| X2 Age | −0.680 | 42.137 | 0.000 *** | 0.507 |

| X3 Household registration (local urban residents) | - | 14.081 | 0.003 *** | -- |

| Local rural residents | −0.102 | 0.045 | 0.832 | 0.903 |

| Migrant urban residents | −0.026 | 0.012 | 0.913 | 0.974 |

| Migrant workers | 0.893 | 13.353 | 0.000 *** | 2.444 |

| X5 Education | −0.467 | 7.862 | 0.005 *** | 0.627 |

| X11 SPI | −0.090 | 4.836 | 0.028 *** | 0.913 |

| X14 PGI | −0.323 | 13.806 | 0.000 ** | 0.724 |

| Constant | 2.086 | 14.352 | 0.000 *** | 8.056 |

| Percentage correct: 79.9% | LR chi2: 94.144 *** | |||

| Nagelkerke R square: 0.133 | ||||

| Variable | B | Wales | Sig. | Exp(B) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X2 Age | −0.655 | 38.05 | 0.000 *** | 0.519 | |

| X3 Household registration | -- | 32.034 | 0.000 *** | -- | |

| Local rural residents | 0.277 | 0.023 | 0.879 | 1.319 | |

| Migrant urban residents | 2.096 | 9.057 | 0.003 *** | 8.132 | |

| Migrant workers | 3.255 | 23.439 | 0.000 *** | 25.913 | |

| X5 Education | −0.447 | 7.167 | 0.007 *** | 0.640 | |

| X11 SPI * X3 Household registration | -- | 9.817 | 0.020 ** | -- | |

| NPI by local rural residents | −0.465 | 2.456 | 0.117 | 0.628 | |

| NPI by migrant urban residents | −0.218 | 3.157 | 0.076 | 0.804 | |

| NPI by migrant workers | −0.261 | 4.186 | 0.041 ** | 0.770 | |

| X14 PGI * X3 Household registration | -- | 20.594 | 0.000 ** | -- | |

| PGI by Local rural residents | 0.290 | 0.290 | 0.590 | 1.336 | |

| PGI by migrant urban residents | −0.75 | 8.681 | 0.003 ** | 0.472 | |

| PGI by migrant workers | −0.844 | 11.612 | 0.001 *** | 0.430 | |

| Constant | 1.095 | 4.574 | 0.032 ** | 2.990 | |

| Percentage correct: 80.1% | LR chi2: 112.126 *** | ||||

| Nagelkerke R square: 0.157 | |||||

| Local Urban Residents | Local Rural Residents | Migrant Urban Residents | Migrant Workers | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | B | Variable | B | Variable | B | Variable | B |

| X2 Age | −0.391 *** | X4 Marriage (Married) | −2.303 *** | X1 Gender (Female) | 1.164 ** | X2 Age | −1.698 *** |

| X10 TGR | −2.654 ** | X13 RFI | 1.304 ** | X5 Education | −2.509 *** | ||

| X14 PGI | −1.569 *** | X8 Dis. | −0.003 ** | ||||

| Constant | −1.151 * | X11 SPI | −0.383 ** | ||||

| X13 RFI | −1.298 *** | ||||||

| Constant | 13.143 *** | ||||||

| Sample Size: 765 | Sample Size: 31 | Sample size: 132 | Sample Size: 96 | ||||

| Percentage Correct: 79.2% | Percentage Correct: 77.4% | Percentage Correct: 80.3% | Percentage Correct: 83.3% | ||||

| LR chi2: 301.297 *** | LR chi2: 17.094 *** | LR chi2: 20.842 *** | LR chi2: 64.438 *** | ||||

| Nagelkerke R Square: 0.434 | Nagelkerke R Square: 0.565 | Nagelkerke R Square: 0.229 | Nagelkerke R Square: 0.653 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhu, Z.; Fu, J.; Zhou, S. How Do Chinese Migrant Workers Avoid Leisure-Time Physical Inactivity? Sustainability 2025, 17, 4700. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104700

Zhu Z, Fu J, Zhou S. How Do Chinese Migrant Workers Avoid Leisure-Time Physical Inactivity? Sustainability. 2025; 17(10):4700. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104700

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhu, Zhanqiang, Jiaying Fu, and Suhong Zhou. 2025. "How Do Chinese Migrant Workers Avoid Leisure-Time Physical Inactivity?" Sustainability 17, no. 10: 4700. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104700

APA StyleZhu, Z., Fu, J., & Zhou, S. (2025). How Do Chinese Migrant Workers Avoid Leisure-Time Physical Inactivity? Sustainability, 17(10), 4700. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104700