Abstract

Climate change is one of the most pressing issues on the public policy agenda. Employing data from rounds 8 and 10 of the European Social Survey, this paper examines the relationship between the perception of Europeans towards climate change and the limitation of energy consumption. An ordered logit model shows that socio-demographic characteristics are strongly related to attitudes towards climate change: female, more educated, and left-leaning respondents display, on average, higher levels of worry and personal responsibility for addressing climate change. However, the relationship between these predictors with greater support for energy reduction measures is non-trivial. Through our unique dataset, the study investigates the evolution of attitudes towards private energy consumption reduction over time. Although beliefs are becoming more positive across Europe, personal responsibility to address climate change seems to play an especially pivotal role in Eastern countries. Policy implications are discussed in light of these results.

1. Introduction

Climate change has been regarded as one of the most pressing issues modern societies have faced over the last few decades [1]. The energy issue has recently gained prominence in the public debate, as the conflict between Russia and Ukraine has limited the supply of fossil fuels, particularly natural gas, and has skyrocketed electricity prices globally. Increasing energy efficiency has become a matter of ecology and public finance for many European countries, whose budgets had already taken a hit after the pandemic [2].

Efforts to address climate change have been largely ineffective, as countries that on paper agree on environmental treaties often fail to meet their stated goals [3]. In place of direct intervention of governmental organizations, many have stressed the importance of personal efforts of consumers to curb carbon emissions, advocating, in particular, the need for private changes in energy consumption habits. Indeed, it is believed that reducing energy demand may be one of the most cost-effective solutions currently available [4], while energy efficiency measures have been estimated to be largely insufficient to meet current environmental goals [5].

Despite the recognized benefits of bottom-up approaches to curbing our ecological footprint, much of this potential has remained untapped [6]. Prior studies suggest that insufficient engagement with climate issues by the general public may be at the root of this failure [7], prompting deeper reflection on the underlying motivations behind climate change rejection and more specifically skepticism towards reducing energy expenditure. To achieve their goal, policymakers need to remove these cognitive and behavioral obstacles, in order to convince the public opinion that climate change is a severe issue, prioritize the sacrifices necessary to mitigate its anthropic roots, and promote effective changes in lifestyle [8].

The present work deepens our knowledge on the topic by analyzing to what degree concern and feelings of personal responsibility towards climate change are associated with greater support for energy use limitation. The specific focus on attitudes and beliefs is very important because in well-founded sociological theories such as the theory of reasoned action and the theory of planned behavior, attitudes and beliefs are considered as the main antecedents of the intentions towards a given behavior; and the intentions are the best predictors for the realization of a behavior in a decision process mechanism. Hence, we use novel data from round 10 of the European Social Survey (ESS), released in December 2022, to look into the attitudes of the European population regarding perceptions of climate change and the need to curb energy consumption. In addition, the continuity between recent releases of the ESS allows us to compare these data with a similar set of items already explored in round 8, which was carried out in 2016.

In particular, we rely on three items drawn from the two surveys. The first item, chosen among those available in rounds 8 and 10 of the ESS, focuses on the responses to the question, “How worried are you about climate change?”. The second one collects the answers to “To what extent do you feel a personal responsibility to try to reduce climate change?”. The third one asks, “[…] Imagine that large numbers of people limited their energy use. How likely do you think it is that this would reduce climate change?”. Conceptually, these three questions try to model the necessary steps that lead to behavioral changes necessary to fight climate change. The first question aims to capture the extent to which respondents are concerned about climate change and its effects on the planet. In contrast, the second is informative about the feeling of personal responsibility regarding the problem, so as to capture to what degree they believe they ought to act to safeguard the climate. Lastly, the third item expresses the perceived effectiveness of a specific mode of environmental harm reduction, namely lower energy consumption (as a tool to limit greenhouse gas emissions).

We test whether the respondents’ personal characteristics tie together these three conceptual steps, that is, whether climate change believers are also the most prone to reducing energy consumption. Therefore, the focus of the paper is two-fold. On the one hand, the ESS round 10 data allow us to study different socio-demographic profiles and their attitudes towards climate change and energy use. On the other hand, the availability of comparative data with pre-COVID and pre-Energy crisis data from round 8 of the ESS makes it possible to evaluate the change in individual orientations towards these topics over time and across regions of Europe. We have adopted an ordinal regression model to achieve our research goals due to the polytomous nature of the response variables.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 carries out a literature review on the perception of climate change and energy reduction as a solution to it. Section 3 discusses the data employed in the study and the variables collected and addresses any missing data problems. Section 4 displays the results from the regressions, with particular attention to divergences across clusters of countries. Finally, Section 5 contains some final remarks on the topic.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Climate Change: Between Skepticism and Engagement

Attitudes regarding climate change and energy consumption have been explored at large by many disciplines in the social sciences, from political science to sociology, economics, and managerial sciences [9]. The awareness and willingness of people to personally bear the cost of lowered ecological impact seem to be a driving factor of unsatisfactory environmental awareness and compliance, even though these issues are universally recognized by experts as crucial to the future of the environment and sustainable economic development (for some seminal studies, see [10,11,12]). Firstly, we must note that “climate change disbelief is not just the result of a lack of awareness or understanding” [13]. Instead, there is a perceived lack of urgency to the problem, widespread skepticism for humans’ role in global warming, and an unwillingness to pay the costs of a green transition. McCright et al. [14,15] provide a helpful review of the main predictors of climate attitudes. They find, for instance, that men are generally more skeptical than women: indeed, it is thought that the way women are socialized makes them more empathic, as well as being more risk-averse than their male counterparts. On a similar note, Zafar and Ammara [16] note that these differences may relate to gaps in health concern and income among respondents of opposite genders, which in turn relates to the level of wealth of the respondents’ country of origin [17].

More recently, Arikan and Gunay [18] found, using data from the Global Attitudes Survey, that years of education, female gender, older age, and higher income are all positive and significant predictors. Education favors political participation and provides individuals with the cognitive tools to grasp the climate issue, while greater economic security allows them to worry less about immediate concerns and refocus on larger issues. Other cognitive, experiential, and socio-cultural factors are analyzed by van der Linden [19], allowing the author’s model to explain a significant proportion of climate change risk perception variability. A recent review finds similarly strong connections between psychosocial traits and broad engagement with the climate issue [20].

Further research highlights the existence of an urban–rural divide. In particular, they stress the differential effects of education and social class levels on support for climate protection and energy reduction in different residential settlements [21]. Arndt et al. [22] explain polarization: climate policies tend to concentrate costs in certain areas already under socio-economics stress because of other processes linked to globalization and modernization, which causes resistance. As a result, the center-periphery cleavage emerges. Rural and suburban residents will be less supportive of green policies, as they fear income losses and reduced purchasing power, mainly for poorer regions.

2.2. Attitudes Towards Climate Change and the European Social Survey

In this rich literature, the European Social Survey has been a source of vast knowledge of what concerns the way inhabitants of the European Union and beyond perceive the issues at hand. In particular, the data collected through this project allow researchers to bridge one of the most notable gaps in the literature, concerning the lack of large-scale cross-national survey data on climate perception [23,24].

Among previous endeavors in this direction, Marquart-Pyatt et al. [25] use data from round 8 of the ESS to examine how the opinions concerning climate change connect to attitudes supportive of renewable energy and energy behavioral intentions across nations. The results show that predictors supporting green policies transcend welfare regimes (except for former socialist governments, which all display a lower interest in the issue). The author’s findings suggest that socio-economic determinants of interest in climate change are broadly similar across the continent. Working on the same set of data, Poortinga et al. [26] confirm these results but argue that the size of the estimated impact of these predictors highly depends on the country of observation. These regional differences across Europe suggest that some underlying heterogeneity, which cannot be explained by economic conditions, still exists. Another recent study by Bouman et al. [27] highlights the existence of strong correlations between biospheric values, personal responsibility towards climate change, climate mitigation policy support, and climate mitigation behaviors.

Another strand of literature has been pursuing the reasons behind the negation of climate change. Lubke [28] shows that rejecting climate change is strongly connected to people’s economic insecurity. However, it also depends on the area’s economic conditions in terms of the region and the country. More rural areas, as well as countries more dependent on fossil fuels, are more skeptical about the involvement of humans in climate change. Personal experiences with natural disasters caused by climate change also seem to affect one’s perception of the phenomenon [29]. While denial is a marginal phenomenon among European populations, many people attribute climate change equally to human influences and natural processes.

2.3. Bottom-Up Solutions: Energy Demand Reduction and Its Limits

Turning to specific policies devised to fight climate change, energy appears to be a key factor, as it is one of the few that the consumer can directly tackle. Prior studies found a correlation between the strength of environmental concerns and greater support for renewable energy sources in Germany [30], intentions to reduce energy use in the UK [29] and to adopt energy-saving behaviors [31], and more general support for green policies [32,33]. More recently, researchers found that a greater risk perception towards climate change is correlated with the perceived ineffectiveness of individual action [34] and that expectations about the efficacy of energy reduction initiatives moderate the association between worry about climate change and energy-saving behaviors [35]. Moreover, Jakučionytė-Skodienė and Liobikienė [36] observe that, while feelings of personal responsibility were positively correlated with personal actions to reduce climate impact, climate change concern only promotes low-cost ones. Belaid and Joumni [37] gathered information about France and found, among other socio-economic indicators, that age has a non-linear effect on energy attitudes. People who worry about energy security negatively distort their preferences for renewable alternatives to fossil fuels [38] or opt for alternatives to fossil fuels only if given no choice [39]. On top of that, their decisions do not consider solely economic advantages, so that they are willing to stray away from promising energy-saving technology in exchange for greater comfort or convenience [40]. Lastly, the political dimension of the problem is a strong driver of beliefs [41]: people appear to be less in favor of energy policies because of their right-wing sympathies [42], while also reducing the positive effects of education on climate change beliefs [43] and displaying perverse interactions with socioeconomic status [44].

Although these papers provide valuable insights into the topic, they all share a critical limitation: they use only one round of cross-sectional data to conclude. This limits our understanding of how climate change and energy perception change over time. That is often the case even for studies that employ data collected over multiple years, as the sample is rarely consistent enough across countries to allow a time-series approach [45]. Our paper aims to bridge this gap by employing repeated cross-sectional data drawn from round 8 (2016) and round 10 (2020) of the European Social Survey. Although the samples of respondents are different, ESS works on large samples that are representative of the countries’ populations.

Only a few published articles and working papers [46] analyze round 10 of the ESS to study the perceptions of climate change and energy use. However, the present approach improves on these papers, combining multiple survey waves and extending the explanatory variables.

3. Data and Methods

3.1. Theoretical Models

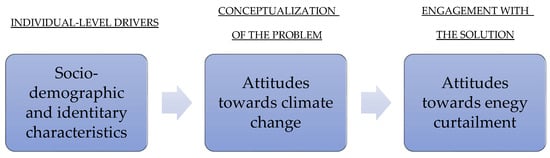

To capture the role of individual beliefs concerning climate change and how these mediate support for energy demand reduction measures, we develop a basic model of behavioral action. This comprises three main clusters of drivers, each capturing a necessary step required for an individual to personally engage with mitigation activities.

In cluster 1, we include socio-demographic variables which are believed to influence beliefs towards science and, in particular, climate change and its anthropogenic nature. These are posited to exogenous to the formation of beliefs, and relate to fundamental aspects of one’s identity, including gender, age, nationality, and socio-economic status. While not all immutable, they are deemed to be sufficiently fundamental and slow changing, so that they are not themselves influenced by the perception of climate change but are rather the cause of such attitudes. Among these we also include religion and political affiliation. Despite the latter being a relatively more complex construct compared to the previously mentioned ones, we include it in the analysis by virtue of the importance granted to it by the literature as an explanatory variable of individual beliefs [47]. Moreover, it is generally recognized as a cause rather than an effect of skepticism, and while feedback loops do exist, they relate more to fostering collective anti-scientific processes than directly determining political faith at the individual level [48].

Cluster 2 includes instead the conceptualization of climate change as a real, impending threat, of which human behaviors, and, in particular, private decisions, are a fundamental root cause. Rather than being a monolithic construct, climate change skepticism appears to be a complex structure of several, often conflicting beliefs about the environment and our relationship with it. As noted by Haltinner and Sarathchandra [49,50], distrust towards climate change should rather be regarded as a continuum of related but distinct positions, where uncertainty about one’s own appraisals plays a crucial role. Among these crucial connections, we chose to isolate the role of individual worry for the consequences of environmental change and individual responsibility towards containing their negative effects as key dimensions of investigation. As attitudes are preconditions for the activation of individuals, as asserted by the theory of reasoned action [51] and theory of planned behavior [52], understanding the causal link between personal view of the problem and attitudes towards its possible solution can provide us with valuable insights.

Finally, cluster 3 contains our main object of study: the attitude towards energy demand reduction as the proposed solution to climate change. Here, as for all environmental attitudes, it is conceptually difficult to isolate a single dimension of analysis capable of capturing the whole spectrum of beliefs related to personal efficacy. Therefore, we chose to concentrate on one of the main advantages of individual action versus government intervention: the lack of coordination failures among countries, which to this day represents one of the main obstacles to effective international action. By contrast, we investigate whether respondents believe that independent action by many private individuals can be an effective tool to reduce environmental transformations.

The connection between these three clusters, represented through the directed acyclic graph (DAG) [53] in Figure 1, will guide the development of our statistical models.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model describing the causal relationship between the investigated constructs.

3.2. Participants and Survey Procedure

The European Social Survey (ESS) has been an academically driven cross-national European survey since 2001. It has been administered every two years in 40 countries and has reached its tenth round as of 2022. It consists of an hour-long face-to-face interview (with some exceptions due to the technical limitations of the COVID-19 pandemic), delivered to newly selected, cross-sectional samples of representative size. Respondents are people aged 15 and over and are residents within private households in the countries of observation, regardless of their nationality and citizenship. The survey involves strict random probability sampling, a minimum target response rate of 70 and rigorous translation protocols.

The survey collects social attitudes, behaviors, and values on various subjects, such as trust in institutions and governments, political values and engagement, social capital and trust, and immigration and crime. Next to several recurring questions that constitute the “core” of the survey, it also alternates two “rotating modules” on varying topics every two years.

Round 8 was conducted between August 2016 and December 2017 and covered 23 countries for 44,387 observations. In addition to the core topics, it collects information on two rotating modules titled “Public Attitudes to Climate Change, Energy Security, and Energy Preferences” and “Welfare Attitudes in a Changing Europe”.

Round 10 was conducted between 2020 and 2022. It covered 32 countries, though, in practice, only 13 of them have relevant data for our research purposes. Therefore, the number of observations is 33,351. The questionnaire contains two unrelated rotating modules; since the items from the first module have been integrated into the core questions of the present survey iteration, we can perfectly map the answers to the questions of interest.

Among the available questions, we selected information about attitudes towards climate change and the reduction in energy consumption in countries with observations for both rounds mentioned. After dropping the missing values, the dataset is composed of 42,081 observations (22,398 from round 8, 19,683 from round 10) over 13 countries: the Czech Republic, Estonia, Finland, France, Hungary, Iceland, Italy, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Slovenia, and Switzerland. Descriptive data for the final sample are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Unweighted sample size and descriptive statistics for age and attitudes towards climate change and energy reduction per country.

3.3. Dependent Variables

In our analysis, we will focus on three dependent variables, described in detail in Table 2. The first one collects the answers to the question: “How worried are you about climate change?”. The values of the responses vary between 0 (“Not at all worried”) and 10 (“Extremely worried”). Other responses (“Not applicable”, “Refusal”, “Don’t know”, “No answer”) are pooled together as missing values. Henceforth, we will refer to this first variable as the worry variable.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of the dependent variables, with percentages for each possible answer.

The second variable captures the answers to the question, “To what extent do you feel a personal responsibility to reduce climate change?”. The values range from 0 (“Not at all”) to 10 (“A great deal”). Other responses (“Not applicable”, “Refusal”, “Don’t know”, “No answer”) are pooled together as missing values. Henceforth, we will refer to this first variable as the responsibility variable.

The last target variable collects the responses to the question, “Imagine that large numbers of people limited their energy use. How likely do you think it is that this would reduce climate change?”. The values range from 0 (“Extremely unlikely”) to 10 (“Extremely likely”). Other responses (“Not applicable”, “Refusal”, “Don’t know”, “No answer”) are pooled together as missing values. Henceforth, we will refer to this first variable as the efficacy variable.

While the worry statistics vary from 1 to 5, with a mean and median value close to the center of the interval (as shown in Table 1), the responsibility and efficacy variables range between 0 and 10. While the former still has a mean/median value close to the center, that is not the case for the latter, which displays consistently lower realizations. Figure 2 presents the relative change in each of the three outcomes observed between the two ESS rounds, expressed in percentage terms.

Figure 2.

Maps of countries included in the sample, displaying the relative change in attitudes between round 8 and 10.

3.4. Explanatory Variables

While the worry statistics vary from 1 to 5, with a mean and median value close to the center of the interval, the responsibility and efficacy variables range between 0 and 10. Moreover, their mean/median value is closer to 6, suggesting that respondents are more clearly positioned on average in these two latter issues than climate worry.

To study the influence of the socio-economic features of the respondents on their attitude towards climate change and its mitigation, we employ nine variables from the ESS. This is a considerable enlargement compared to similar studies on the subject. These are (1) Age, the age of the respondent at the time of the interview, which is grouped in 7 ten-year brackets; (2) Gender, the gender of the respondent; (3) Employment, the employment status of the respondent, split into 7 categories (“Employed”, “Unemployed”, “Student”, “Sick”, “Retired”, “Stay-at-home”, “Other employment condition”); (4) Not citizen, whether the respondent is not a citizen of the country; (5) Foreign, whether the respondent was not born in the country; (6) Education, the maximum level of education of the respondent, represented by their ISCED score, grouped in 3 categories (“Primary”, “Secondary”, and “Tertiary” education); (7) Income, the household’s total net income, from all sources, divided into 3 categories (“Low” for the first three deciles of the national distribution, “Medium” for the middle four, and “High” for the highest three); (8) Political beliefs, represented by a scale between 0 (for left-wing) and 10 (for right-wing), were then grouped into two dummy variables; (9) Domicile, how the respondent would describe the area where they live in terms of size (categorized as “Rural” if their response was “Farmhouse”, “House in the countryside”, and “Urban” if they answered “Town or small city”, “Suburbs or outskirts”, or “Big city”).

Along with these key socio-economic variables, we include geographical controls in the form of dummies for each of the 13 countries under study. We aim to rule out any time-invariant characteristic of the country populations that may be otherwise confounded for a causal effect of one of the abovementioned predictors.

Lastly, in the latter stage of the analysis, we employ a dummy variable for former socialist state countries, which we will refer to as Central and Eastern European (CEE): the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Lithuania, and Slovenia. We contrast them with the rest of the countries in the sample (Switzerland, Finland, France, Italy, Iceland, Norway, and Portugal), identified with the acronym ROE. This distinction follows the results found in McCright et al. [14], whose authors argue that the most notable differences in climate change and energy attitudes are found in countries that belonged to the Eastern Block after World War II.

3.5. Data Analysis

To test the predictive potential of our model of behavioral activation, the analyses employ a battery of statistical techniques, which aim to establish robust correlations between our variables of interest.

In the first part of the analysis, we seek to establish a relationship between individual-level drivers and attitudes towards climate change and energy reduction behaviors. The results from three ordered logistic models (estimated using maximum likelihood) for each variable of interest are reported in the following section.

Subsequently, we employ a mediation approach to understand whether the inclusion of climate related items weakens the effect of the energy variable or if, instead, there is an independent change in the attitude towards energy reduction measures. The goal is to understand how individual conceptualization of the problem plays a role in promoting energy conscious behaviors.

Finally, the same mediation analysis is applied to two distinct clusters of countries to observe whether there are significant heterogeneities in relevant predictors and time trends. Comparing Central and Eastern European countries (CEE) with the Rest of Europe (ROE) allows us to grasp potential patterns of divergence that may have emerged.

Tables containing the results of these analyses are presented in the next section.

4. Empirical Results and Discussion

4.1. Attitudes Towards the Origin of Climate Change

We found some expected results and new insights after excluding non-admissible values for the variables of interest.

From the first column of Table 3, the ordinal logit model helps us isolate a number of key variables impacting worry about climate change. The estimations suggest that female gender has a significant and positive effect on the response, meaning that women are more likely to worry about the consequences of climate change than men. Age follows an interesting U-shaped trajectory: younger respondents appear to be the least concerned, with no detectable difference between respondents under 20 and those under 29. The likelihood of a high worry score increases as the respondents get older, peaking between 50 and 69 years old and finally decreasing (but only in relative terms) for those over 70.

Table 3.

Weighted regression on the climate and energy variables.

Education is a relevant predictor for greater environmental concern, with a stronger effect for higher levels of schooling. At the same time, controlling for education, there is no independent effect exerted by income. Out of all employment statuses, the students, the unemployed, and the sick appear to be the most concerned with climate change, while workers, stay-at-home parents, and the retired display no statistical difference.

While citizenship does not explain worry, foreign-born respondents feel more threatened than native ones. Moreover, there is compelling evidence that urban living settlements are conducive to a high worry score, though the effect size is rather small. Lastly, political affiliation to the right wing is conducive to a lower likelihood of worrying about the environment.

An exciting yet novel fact is that there is a discernible change in opinions between 2016 and 2020 regarding the perceived risk of climate change: the variable capturing the round of the observation is strongly significant, with a positive sign showing that people are becoming more concerned about the environmental threat. Considering the relatively narrow time window of the study, it is somewhat surprising and encouraging to observe increasing awareness of the consequences of human activity on the global environment.

In column 2 of Table 3, we observe the socio-demographic predictors correlating with a stronger feeling of personal responsibility for safeguarding the environment. The female gender exerts a similarly positive effect on the likelihood of a high score, as does education, with a magnitude increasing with the level of schooling. Age follows a similar path as before, though the positive effect starts from 20 to 29 respondents, reaching its maximum again between age 60 and 69. Surprisingly, however, income has a distinctly positive and significant impact on feelings of direct responsibility for addressing climate change, a result that was not found for worry. A similar, relevant significance shift is seen in living settlements: the responses to the responsibility question do not appear to be different for urban respondents compared to their rural counterparts. Returning to employment status, students, and those unable to work exhibit higher scores while foreign respondents are still more likely to feel personally responsible for the climate with respect to non-citizens. Political beliefs are once again significantly associated with a reduction in the likelihood of a high score of the outcome variable, with right-wing respondents being more skeptical of the importance of their involvement.

Once again, there seems to be a general trend of improvement over time in the perception of climate change as a problem requiring the direct intervention of individuals. The estimated coefficient is positive, sizeable, and significant, suggesting that people are becoming more willing to change their behavior to fight climate change across Europe. However, whether this general disposition translates into a greater belief in energy reduction is not a priori given and will be the focus of the following subsection.

4.2. Attitudes Towards Energy Reduction by Individuals

While analogies can be found compared to the previous regressions, there are key differences between climate attitudes and opinions regarding the potential for private efforts to reduce energy demand. We turn to the third column of Table 3, which contains the results from the regression on the efficacy of energy limitation as a measure to fight climate change.

Gender is once again a significant predictor, with women being far more supportive of reduced energy consumption than men. Similar to the responsibility item, but not the worry one, income positively correlates with the outcome variable, with stronger support displayed by wealthier respondents. Education has a significant positive effect on the variable only for relatively high levels while holding a secondary education does not influence the support for energy reduction measures. Looking at employment status, only students significantly differ from the employed in terms of higher support for lowering energy consumption, while all other categories do not.

Neither lack of citizenship nor foreign origins explain attitudes towards energy reduction. Living arrangements are once again non-significant in the present regression. Lastly, being politically right-wing decreases the chances of holding strong beliefs in the effectiveness of reducing energy consumption.

That said, we still observe a general trend of improvement in the perception of energy reduction measures as effective in solutions to climate change, as the variable capturing the round of observation is once again positive and significant. This result is robust to the inclusion of the aforementioned socio-demographic controls. In the next section, we will analyze how attitudes towards energy reduction measures interact with attitudes towards climate change. In doing so, we will limit the presentation of coefficients to those that we found to be more consistent across regressions and conceptually interesting.

4.3. Role of Climate Change Perception in Explaining Attitudes Towards Energy Reduction

In the following Table 4, we will present the results for these two measures of attitudes towards climate change on the likelihood of supporting the effectiveness of energy demand reduction:

Table 4.

Regression on energy efficacy mediated by climate worry and climate responsibility.

The coefficient for the variable capturing the degree of concern exhibited by respondents is significant and very sizeable, suggesting a positive correlation between one worry about climate change and their belief in reducing energy consumption to mitigate it. At the same time, including the worry variable appears to change some of the previously reached conclusions. First of all, the effect of schooling becomes more multifaceted. Rather than simply predicting a higher level of support for energy reduction measures, it appears that much of tertiary education’s impact relates to a different attitude towards climate concerns. This can be seen by the fact that the coefficient for higher education shrinks considerably, while secondary education becomes significant but negative.

By including the perception of private responsibility in addressing climate change, this effect on education becomes even stronger, with a barely significant, small positive effect of tertiary education and a much stronger and significant reduction in support for energy reduction for respondents with only secondary education. Moreover, another important shift is seen concerning income, for which the size of coefficients becomes much smaller across all levels. Lastly, the introduction of the responsibility variable has also reduced the effect of the variable capturing the round of observation, for which the coefficient becomes less than half its original magnitude. This suggests that a great deal of the observed improvement in attitudes towards energy reduction can be attributed to climate change perception, specifically a change in the perceived responsibility in addressing its problems.

4.4. Regional Heterogeneities in the Effects of Socioeconomic Predictors

Looking at the picture we presented, we observed that some predictors bear consistent significance over the three questions, suggesting that specific socio-demographic characteristics offer good approximations of the profile of climate change believers who also support energy consumption reduction to tackle the problem. However, some of these predictors fail to hold as consistently once we use mediation analysis to understand how climate attitudes may explain attitudes towards energy reduction.

To better understand whether more complex dynamics across coefficients are hidden underneath the surface of our sample of countries, we need to look at potential regional heterogeneities in the patterns of significance. Drawing on the literature on the topic, we divide European countries into two groups: Central and Eastern European countries and the rest of Europe. We present the results from these separate regressions in Table 5.

Table 5.

Regression on energy efficacy mediated by climate worry and climate responsibility, by geographic region.

First, looking at the first and fourth columns, we can observe apparent differences in how predictors influence attitudes towards energy reduction. Most notably, income and education are insignificant for Central and Eastern European countries. Right-wing associations also appear to be a non-meaningful predictor of the outcome in these regions, while they have a stronger effect in the rest of the continent. Instead, the round variable for the rest of Europe is much lower than for Central and Eastern Europe, suggesting that perhaps they are experiencing a much faster increase in beliefs for energy reduction than the other countries.

However, including the two variables capturing attitudes towards climate change tells a different story. These appear to have comparable size and significance across the two areas, positively correlating with the outcome studied. That said, it appears that the responsibility variable, when introduced for CEE countries, renders the variable for the round of observation insignificant. Surprisingly, that is the case for respondents’ gender, so there appears to be no significant difference between men and women in their opinions towards curbing energy consumption once we account for their perceived responsibility towards climate change. The analysis suggests that, despite growing much faster throughout the observation, Central and Eastern European countries did not experience a systematic improvement in the perceived effectiveness of energy reduction measures.

5. Discussion

The prior analysis allowed us to understand the importance of several socio-demographic predictors in explaining the attitudes towards climate change and energy reduction.

A relatively coherent picture of the situation can be gathered from the first two regressions on the worry about climate change and the feeling of personal responsibility in addressing the threat it represents. Coherently with the literature, we see that females and better educated and politically left-leaning people are more likely to show greater concern for the climate and have a stronger perceived duty to act to mitigate its negative consequences. The existence of the gender gap, also in light of previous results finding contrasting evidence on this topic [54], seems to reinforce the idea that women as caregivers are naturally more prone to care about others, which is further reinforced by the fact that they appear to be more likely to shift to the left of the political spectrum as material conditions improve [17]. The non-linear effect of age on climate beliefs matches the results from Arıkan and Gunay [18] and supports the idea of a curvilinear relationship between the two variables. Similarly, being a student, too sick to work, or unemployed to a lesser degree reinforces the likelihood of holding progressive beliefs on climate change. Instead, less concerned respondents tend to be male, less educated, and politically right-wing. Interestingly, specific socio-demographic markers, such as being born abroad, increase the likelihood of a high score across both dimensions. This may be the case because they correlate with a general disposition to be more progressive, promoting worry and perceived responsibility towards climate change.

However, not all predictors carry over from one regression to the other. Income only seems to meaningfully impact perceived responsibility, while that is not the case for worry about climate change.

The results in the third regression, designed to capture what the literature calls “collective efficacy”, share some similarities with the attitudes towards climate change. Supporters of the efficacy of energy reduction share some traits with more environmentally friendly respondents: they tend to be women, politically left-leaning, and with higher levels of schooling. However, significant divergences in patterns suggest that believing in the urgency of a problem and the importance of our intervention is mainly different from the effectiveness of one specific solution to tackle it. For instance, age seems to have an opposite effect on faith for energy reduction measures, while secondary education has no predictive power despite being a clear predictor of climate change awareness. Conversely, income only matters for personal responsibility and energy demand reduction support, not for personal worry. Finally, other predictors, such as marital, employment, and immigration status, display very weak patterns of significance regarding attitudes towards energy reduction.

6. Conclusions

Perhaps the greatest lesson we can draw from the study is the need to distinguish between these three concepts, which come together to shape the willingness to support and act to reduce private energy consumption. Firstly, people may not be personally concerned with the consequences of climate change, as they may think it is a natural phenomenon that does not appear to threaten their current way of life. Secondly, it may be that, despite their worry about the planet’s future, they are not convinced about their own personal responsibility to reduce environmental damage, as they may acknowledge their efforts to reduce their carbon footprint (e.g., recycling, taking public transport) are sufficient. Lastly, people may distrust energy demand reduction as an effective solution to the problem. Arguments can be made that, while essential to the goal, private efforts to reduce environmental harm are neither sufficient nor central to addressing the problem. Instead, the main culprits are the insufficient taxation and regulations on big corporations and their polluting activities, the failure of international negotiations on environmental treaties, and the lack of effective green financial markets. Campaigns to reduce energy consumption may be perceived as trying to guilt private citizens into reducing essential energy consumption, so supporters of this view advocate for governmental action. Studies on the topic should acknowledge the complementarity of these three steps in allowing private actions to be meaningfully undertaken while also recognizing the unique predictors that influence each of those differences.

A second key result from the study is that overall attitudes towards climate change and energy reduction measures have improved over the years. To better understand how they interact, we used mediation analysis to observe how climate worry and personal responsibility shape the perception of private energy demand. The main takeaway is that a large part of the improvement in energy reduction support is due to an increased belief in the threat of climate change, as the two variables bear a largely positive and significant correlation with the outcome. Specifically, the role of personal responsibility in addressing it explains a sizeable portion of why respondents in 2020 tend to be more favorable to energy reduction measures than in 2016.

Following the literature, we also analyze Central and Eastern European countries separately from the rest, as they seem to display relevant differences in attitudes. Indeed, education, income, and right-wing political affiliation only seem to matter as a predictor outside of former socialist state countries. These results are broadly consistent with findings from Poortinga et al. [26], which find smaller effects of predictors on climate change perception and extend them to energy reduction. Most importantly, once we introduce climate change measures, the variable capturing the round of observation turns insignificant, meaning that CEE countries do not experience an independent improvement of attitudes towards energy reduction measures, something we observe instead for the rest of Europe.

This study provides new evidence that society is becoming more aware of the threat of climate change and is embracing a favorable view towards energy demand reduction as a practical solution. Since data were collected before the beginning of the recent energy crisis, the economic convenience of reducing energy consumption may increase even further over the following years. It is puzzling that former state socialist countries do not show any improvements in the perceived effectiveness of energy reduction measures outside of their stronger beliefs in climate change beliefs. Further research on the topic should be carried out to ensure that the observed positive trends will be long-lasting. In addition, future research agenda should also investigate different beliefs of individuals for different energy sources. Indeed, the effort towards a reduction in energy consumption has to be supported for those sources of energy that produce negative externalities such as carbon emissions, but different strategies for obtaining energy may be considered. In order to provide a development and a further step with respect to the conclusions of the present studies, different data should be analyzed to address the attitudes of European people towards alternatives to the traditional carbon-based sources of energy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.S. and G.C.; methodology, E.S.; software, G.C.; validation, B.S.S., G.C. and E.S.; formal analysis, G.C.; investigation, E.S. and B.S.S.; resources, B.S.S.; data curation, G.C.; writing—original draft preparation, G.C. and E.S.; writing—review and editing, G.C., B.S.S. and E.S.; visualization, G.C.; supervision, E.S. and B.S.S.; project administration, B.S.S.; funding acquisition, B.S.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The data used in this study are publicly available from the European Social Survey (ESS), which follows strict ethical guidelines and obtains informed consent from all participants. As the research involves secondary analysis of fully anonymized and publicly accessible data, additional ethical approval was not required.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study from European Commission.

Data Availability Statement

Data are freely available in the public repository of the European Social Survey at https://www.europeansocialsurvey.org/ (last accessed on 15 April 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ESS | European Social Survey |

| CC | Climate Change |

| CEE | Central and Eastern European Countries) |

| ROE | Rest of Europe (not Central and Eastern Countries) |

References

- Detemple, J.; Kitapbayev, Y. The value of green energy under regulation uncertainty. Energy Econ. 2020, 89, 104807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Monetary Fund. Fiscal Monitor October 2022: Helping People Bounce Back. 2022. Available online: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/FM/Issues/2022/10/09/fiscal-monitor-october-22 (accessed on 1 June 2023).

- Geiges, A.; Nauels, A.; Parra, P.Y.; Andrijevic, M.; Hare, W.; Pfleiderer, P.; Schaeffer, M.; Schleussner, C.-F. Incremental improvements of 2030 targets insufficient to achieve the Paris agreement goals. Earth Syst. Dyn. 2020, 11, 697–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorrell, S. Reducing energy demand: A review of issues, challenges and approaches. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 47, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriarty, P.; Honnery, D. Energy efficiency or conservation for mitigating climate change? Energies 2019, 12, 3543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, D.; Barrett, J.; Wiedenhofer, D.; Macura, B.; Callaghan, M.; Creutzig, F. Quantifying the potential for climate change mitigation of consumption options. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 093001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifford, R. The dragons of inaction: Psychological barriers that limit climate change mitigation and adaptation. Am. Psychol. 2011, 66, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konisky, D.M.; Hughes, L.; Kaylor, C.H. Extreme weather events and climate change concern. Clim. Change 2016, 134, 533–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson-Hazboun, S.K.; Krannich, R.S.; Robertson, P.G. Public views on renewable energy in the Rocky Mountain region of the United States: Distinct attitudes, exposure, and other key predictors of wind energy. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2016, 21, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzoni, I.; Pidgeon, N.F. Public views on climate change: European and USA perspectives. Clim. Change 2006, 77, 73–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugliese, A.; Ray, J. A heated debate: Global attitudes toward climate change. Harv. Int. Rev. 2009, 31, 64. [Google Scholar]

- Poortinga, W.; Spence, A.; Whitmarsh, L.; Capstick, S.; Pidgeon, N.F. Uncertain climate: An investigation into public scepticism about anthropogenic climate change. Glob. Environ. Change 2011, 21, 1015–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockwood, M. Right-wing populism and the climate change agenda: Exploring the linkages. Environ. Politics 2018, 27, 712–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCright, A.M.; Dunlap, R.E.; Marquart-Pyatt, S.T. Political ideology and views about climate change in the European Union. Environ. Politics 2016, 25, 338–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCright, A.M.; Marquart-Pyatt, S.T.; Shwom, R.L.; Brechin, S.R.; Allen, S. Ideology, capitalism, and climate: Explaining public views about climate change in the United States. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2016, 21, 180–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, S.; Ammara, S. Variations in climate change views across Europe: An empirical analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 442, 141157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, S.S.; Clayton, A. Facing change: Gender and climate change attitudes worldwide. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 2023, 117, 591–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arikan, G.; Gunay, D. Public attitudes towards climate change: A cross-country analysis. Br. J. Politics Int. Relat. 2021, 23, 158–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Linden, S. The social-psychological determinants of climate change risk perceptions: Towards a comprehensive model. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 41, 112–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipriani, E.; Frumento, S.; Gemignani, A.; Menicucci, D. Personality traits and climate change denial, concern, and proactivity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Environ. Psychol. 2024, 95, 102277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, T.W.; Kim, J.; Son, J. Public attitudes toward climate change and other environmental issues across countries. Int. J. Sociol. 2017, 47, 62–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arndt, C.; Halikiopoulou, D.; Vrakopoulos, C. The centre-periphery divide and attitudes towards climate change measures among western Europeans. Environ. Politics 2022, 32, 381–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.M.; Markowitz, E.M.; Howe, P.D.; Ko, C.Y.; Leiserowitz, A.A. Predictors of public climate change awareness and risk perception around the world. Nat. Clim. Change 2015, 5, 1014–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, K.W. Public awareness and perception of climate change: A quantitative cross-national study. Environ. Sociol. 2016, 2, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquart-Pyatt, S.T.; Qian, H.; Houser, M.K.; McCright, A.M. Climate change views, energy policy preferences, and intended actions across welfare state regimes: Evidence from the European social survey. Int. J. Sociol. 2019, 49, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poortinga, W.; Whitmarsh, L.; Steg, L.; Bohm, G.; Fisher, S. Climate change perceptions and their individual-level determinants: A cross-European analysis. Glob. Environ. Change 2019, 55, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouman, T.; Verschoor, M.; Albers, C.J.; Böhm, G.; Fisher, S.D.; Poortinga, W.; Whitmarsh, L.; Steg, L. When worry about climate change leads to climate action: How values, worry and personal responsibility relate to various climate actions. Glob. Environ. Change 2020, 62, 102061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubke, C. Socioeconomic roots of climate change denial and uncertainty among the European population. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 2022, 38, 153–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, A.; Poortinga, W.; Butler, C.; Pidgeon, N.F. Perceptions of climate change and willingness to save energy related to flood experience. Nat. Clim. Change 2011, 1, 46–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engels, A.; Hüther, O.; Schäfer, M.; Held, H. Public climate-change skepticism, energy preferences and political participation. Glob. Environ. Change 2013, 23, 1018–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitmarsh, L. Behavioural responses to climate change: Asymmetry of intentions and impacts. J. Environ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlap, R.E.; McCright, A.M.; Yarosh, J.H. The political divide on climate change: Partisan polarization widens in the US. Environ. Sci. Policy Sustain. Dev. 2016, 58, 4–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syropoulos, S.; Markowitz, E.M. Perceived responsibility to address climate change consistently relates to increased pro-environmental attitudes, behaviors and policy support: Evidence across 23 countries. J. Environ. Psychol. 2022, 83, 101868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, B.; Brewer, M.B.; Hayes, B.K.; McDonald, R.I.; Newell, B.R. Predicting climate change risk perception and willingness to act. J. Environ. Psychol. 2019, 65, 101331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregersen, T.; Doran, R.; Böhm, G.; Poortinga, W. Outcome expectancies moderate the association between worry about climate change and personal energy-saving behaviors. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0252105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakučionytė-Skodienė, M.; Liobikienė, G. Climate change concern, personal responsibility and actions related to climate change mitigation in EU countries: Cross-cultural analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 281, 125189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belaid, F.; Joumni, H. Behavioral attitudes towards energy saving: Empirical evidence from France. Energy Policy 2020, 140, 111406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casamassima, A.; Falcone, P.M.; Sapio, A.; Tiranzoni, P. Assessing energy misperception in Europe: Evidence from the European social survey. Energy Sources Part B Econ. Plan. Policy 2022, 17, 2042428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corner, A.; Venables, D.; Spence, A.; Poortinga, W.; Demski, C.; Pidgeon, N. Nuclear power, climate change and energy security: Exploring British public attitudes. Energy Policy 2011, 39, 4823–4833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zundel, S.; Stieß, I. Beyond profitability of energy-saving measures—Attitudes towards energy saving. J. Consum. Policy 2011, 34, 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, A. Political orientation, environmental values, and climate change beliefs and attitudes: An empirical cross country analysis. Energy Econ. 2017, 63, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gromet, D.M.; Kunreuther, H.; Larrick, R.P. Political ideology affects energy- efficiency attitudes and choices. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 9314–9319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czarnek, G.; Kossowska, M.; Szwed, P. Right-wing ideology reduces the effects of education on climate change beliefs in more developed countries. Nat. Clim. Change 2021, 11, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballew, M.T.; Pearson, A.R.; Goldberg, M.H.; Rosenthal, S.A.; Leiserowitz, A. Does socioeconomic status moderate the political divide on climate change? The roles of education, income, and individualism. Glob. Environ. Change 2020, 60, 102024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvaløy, B.; Finseraas, H.; Listhaug, O. The publics’ concern for global warming: A cross-national study of 47 countries. J. Peace Res. 2012, 49, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, C.R.G.; Kocag, E.K. Dynamics of self-belief to fight against climate change: Evidence from European social survey. In Positive and Constructive Contributions for Sustainable Development Goals; Popescu, C.R.G., Ed.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2023; pp. 53–75. [Google Scholar]

- Bayes, R.; Druckman, J.N. Motivated reasoning and climate change. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 2021, 42, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornsey, M.J.; Lewandowsky, S. A toolkit for understanding and addressing climate scepticism. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2022, 6, 1454–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haltinner, K.; Sarathchandra, D. Considering attitudinal uncertainty in the climate change skepticism continuum. Glob. Environ. Change 2021, 68, 102243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haltinner, K.; Sarathchandra, D. Predictors of Pro-environmental Beliefs, Behaviors, and Policy Support among Climate Change Skeptics. Soc. Curr. 2022, 9, 180–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. A Bayesian analysis of attribution processes. Psychol. Bull. 1975, 82, 261–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Processes 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearl, J. Causality: Models, Reasoning, and Inference, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Elert, N.; Lundin, E. Gender and climate action. Popul. Environ. 2022, 43, 470–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).