South African Township Consumers’ Recycling Engagement and Their Actual Recycling Behavior

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

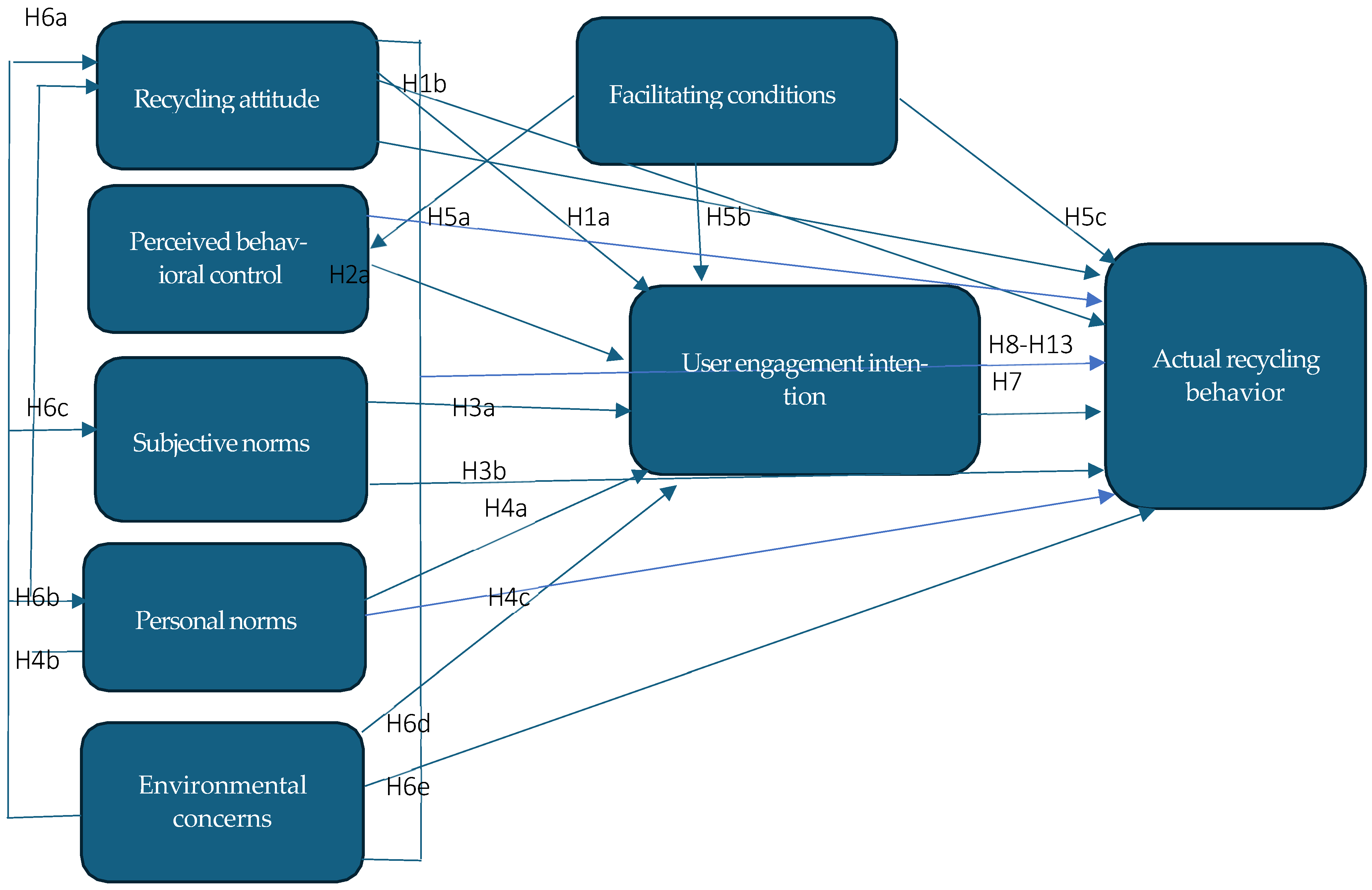

2.1. The Extended Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB)

| Model Applied and Source | Country | Context | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| TPB [8] | SA | Urban consumers recycling behavior | All three TPM constructs influence recycling intention |

| TPB [75] | SA | Urban middle income consumers- recyclers and non-recyclers | Attitude and social norms influenced both recyclers and no-recyclers while perceived behavioral control did not have a significant effect on non-recyclers |

| TPB model and Schwartz’s Value Theory (1992) [76] | Mexico | e-waste recycling | All three TPM constructs influence recycling intention. Social norms reduce the overall predictive power of the model. |

| Extended TPB [77] | United Arab Emirates (UAE) | e-waste recycling intention/young consumers | Subjective norms and behavioral control do not influence e-waste recycling |

| TPB [78] | USA | Public Service Announcement (PSA) video on recycling engagement | All three TPM constructs influence recycling intention |

| Extended TPB [79] | Ghana | Acceptability and use of waste bin | Attitude and subjective norms influence Acceptability and use of waste bin. Perceived behavioral control did not have such influence |

| TPB [80] | Ghana | Households’ source separation intention | Attitude and subjective norms influence households’ source separation intention. Perceived behavioral control did not have such influence |

| TPB [81] | Nigeria | Urban consumers, Lagos | Attitude and effect on recycling intention while social norms did not have such an effect. Perceived behavioral control influenced purchase behavior |

| TPB [82] | India | e-waste recycling | All three TPB constructs influence recycling intention |

| TPB [83] | Bangladesh | Recycling behavior | Attitude and Perceived Behavioral Control insignificant at 95% confidence level while social norm is completely insignificant |

| TPB [26] | Lithuania | Textile waste recycling | All three TPB constructs influence recycling intention |

| TPB [35] | Algeria | Green Start-Ups for Collection of Unwanted Drugs | All three TPB constructs influence recycling intention |

2.2. Recycling Engagement

2.2.1. Recycling Attitude (RA) and Actual Recycling Behavior (AB)

2.2.2. Perceived Behavioral Control [PBC] and Actual Recycling Behavior (AB)

2.2.3. Subjective Norms [SN] and Actual Recycling Behavior (AB)

2.2.4. Personal Norms (PN) and Actual Recycling Behavior (AB)

2.2.5. Facilitating Conditions (FC) and Actual Recycling Behavior (AB)

2.2.6. Environmental Concerns (EC) and Actual Recycling Behavior (AB)

2.2.7. Recycling User Engagement and Actual Recycling Behavior (AB)

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Target Population

3.2. Measures

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Validity and Reliability

| Construct | Item | Factor Loadings | Cronbach’s Alpha | Composite Reliability | Average Variance Extracted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RA | RA 1 | 0.863 | 0.847 | 0.859 | 0.671 |

| RA 1 | 0.701 | ||||

| RA 1 | 0.788 | ||||

| PBC | PBC 1 | 0.782 | 0.835 | 0.842 | 0.576 |

| PBC 2 | 0.760 | ||||

| PBC 3 | 0.776 | ||||

| PBC 4 | 0.844 | ||||

| SN | SN 1 | 0.845 | 0.833 | 0.877 | 0.725 |

| SN 2 | 0.777 | ||||

| SN 3 | 0.873 | ||||

| PN | PN 1 | 0.797 | 0.825 | 0.829 | 0.619 |

| PN 2 | 0.695 | ||||

| PN 3 | 0.779 | ||||

| EC | EC 1 | 0.867 | 0.890 | 0.894 | 0.738 |

| EC 2 | 0.807 | ||||

| EC 3 | 0.856 | ||||

| FC | FC 1 | 0.810 | 0.876 | 0.835 | 0.630 |

| FC 2 | 0.657 | ||||

| FC 3 | 0.792 | ||||

| I | I 1 | 0.864 | 0.902 | 0.906 | 0.763 |

| I 2 | 0.827 | ||||

| I 3 | 0.885 | ||||

| ARB | ARB 1 | 0.600 | 0.758 | 0.770 | 0.532 |

| ARB 2 | 0.781 | ||||

| ARB 3 | 0.635 |

| PN | AB | EC | FC | PBC | RA | SN | UE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PN | ||||||||

| AB | 0.590 | |||||||

| EC | 0.543 | 0.343 | ||||||

| FC | 0.511 | 0.645 | 0.400 | |||||

| PBC | 0.613 | 0.507 | 0.615 | 0.558 | ||||

| RA | 0.260 | 0.304 | 0.459 | 0.222 | 0.483 | |||

| SN | 0.657 | 0.490 | 0.418 | 0.419 | 0.537 | 0.172 | ||

| UE | 0.477 | 0.567 | 0.453 | 0.459 | 0.614 | 0.613 | 0.396 |

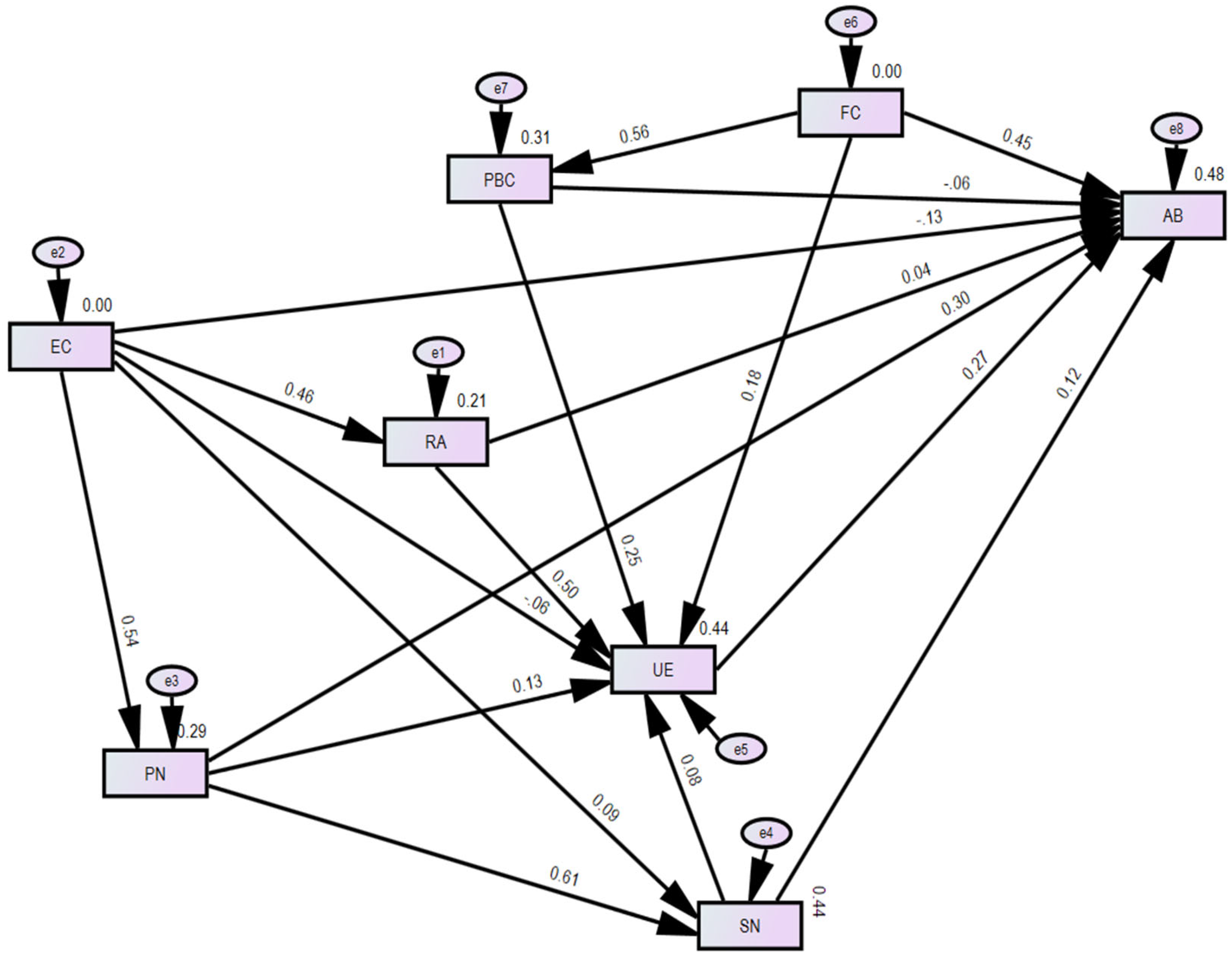

4.2. Hypothesis Testing: Direct Relationships

| Hypotheses | Standard Beta Coefficient | S.E. | t-Values | p-Values | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1a | 0.499 | 0.073 | 6.836 | 0.001 | Supported |

| H1b | 0.177 | 0.073 | 2.565 | 0.001 | Supported |

| H2a | 0.253 | 0.080 | 3.163 | 0.001 | Supported |

| H2b | 0.004 | 0.080 | 0.044 | 0.986 | Rejected |

| H3a | 0.076 | 0.052 | 1.462 | 0.143 | Rejected |

| H3b | 0.142 | 0.057 | 2.491 | 0.013 | Supported |

| H4a | 0.181 | 0.060 | 3.017 | 0.001 | Supported |

| H4b | 0.609 | 0.050 | 12.180 | 0.001 | Supported |

| H4c | 0.421 | 0.060 | 6.379 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H5a | 0.318 | 0.066 | 4.818 | 0.001 | Supported |

| H5b | 0.496 | 0.066 | 7.515 | 0.001 | Supported |

| H5c | 0.557 | 0.045 | 12.378 | 0.001 | Supported |

| H6a | 0.462 | 0.067 | 6.896 | 0.001 | Supported |

| H6b | 0.542 | 0.050 | 10.840 | 0.001 | Supported |

| H6c | 0.418 | 0.058 | 7.207 | 0.001 | Supported |

| H6d | 0.278 | 0.088 | 3.159 | 0.001 | Supported |

| H6e | 0.115 | 0.063 | 1.825 | 0.056 | Supported |

| H7 | 0.274 | 0.068 | 4.029 | 0.001 | Supported |

| Path | Total Effect | Direct Effect | Indirect Effect | S.E. | t-Val | p-Val | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H8: RA → UE → AB | 0.203 | 0.047 | 0.156 | 0.049 | 3.184 | 0.001 | Supported |

| H9: PBC → UE → AB | 0.005 | −0.073 | 0.078 | 0.030 | 2.600 | 0.001 | Supported |

| H10: SN → UE → AB | 0.119 | 0.102 | 0.018 | 0.013 | 1.385 | 0.104 | Rejected |

| H11: PN → UE→ AB | 0.382 | 0.270 | 0.033 | 0.017 | 1.941 | 0.007 | Supported |

| H12: FC → UE → AB | 0.434 | 0.390 | 0.042 | 0.018 | 2.333 | 0.001 | Supported |

| H13: EC → UE → AB | 0.185 | −0.133 | −0.016 | 0.022 | −0.727 | 0.364 | Rejected |

4.3. Hypotheses Testing: Indirect Relationships

5. Discussions and Implications

6. Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical Recommendations

6.2. Practical Recommendations

6.3. Limitation and Directions for Future Research

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tsheleza, V.; Ndhleve, S.; Kabiti, H.M.; Nakin, M.D.V. Household solid waste quantification, characterisation and management practices in Mthatha City, South Africa. Int. J. Environ. Waste Manag. 2022, 29, 208–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busitech. How Much Rubbish We Dump in South Africa Each Day. 2016. Available online: https://businesstech.co.za/news/trending/123769/how-much-rubbish-you-dump-in-south-african-each-day/ (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Dlamini, M.V. Perceptions of Informal Local Traders on the Influence of Emerging Markets: Umlazi and Kwa-Mashu Townships. Master’s Thesis, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Thoo, A.C.; Tee, S.J.; Huam, H.T.; Mas’od, A. Determinants of recycling behavior in higher education institution. Soc. Responsib. J. 2022, 18, 1660–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Marketing Association. People Recycle More When They Know What Recyclable Waste Becomes. 2019. Available online: www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2019/05/190516103712.htm (accessed on 3 December 2024).

- Department of Environmental Affairs. State of Waste Report South Africa. 2018. Available online: http://sawic.environment.gov.za/?menu=346 (accessed on 30 August 2024).

- Xia, Z.; Gu, Y.; Li, J.; Xie, J.; Liu, F.; Wen, X.; Tian, X.; Zhang, C. Do behavioral interventions enhance waste recycling practices? Evidence from an extended meta-analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 385, 135695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strydom, W. Applying the theory of planned behavior to recycling behavior in South Africa. Recycling 2018, 3, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varotto, A.; Spagnolli, A. Psychological strategies to promote household recycling: A systematic review with meta-analysis of validated field interventions. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 51, 168–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froestad, J. Environmental health problems in Hout Bay: The challenge of generalising trust in South Africa. J. S. Afr. Stud. 2005, 31, 333–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, R.K.; Yongsheng, Z.; Jun, D. Municipal solid waste management challenges in developing countries: Kenyan case study. Waste Manag. 2006, 26, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conradie, B.; Hansen, I.L.; Oosthuizen, M. Experiences with and the viability of a recycling pilot project in a Cape Town township. Dev. S. Afr. 2019, 36, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, E.E. Attitudes and practices of households toward waste management and recycling in Nelson Mandela Bay. J. Contemp. Manag. 2020, 17, 573–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denner, C. Assessment of Barriers Preventing Recycling Practices Among Bars and Eateries in Central South Africa. Master’s Dissertation, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kamleitner, B.; Thürridl, C.; Martin, B.A. Cinderella story: How past identity salience boosts demand for repurposed products. J. Mark. 2019, 83, 76–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adu-Gyamfi, G.; Asamoah, A.N.; Nketiah, E.; Obuobi, B.; Adjei, M.; Cudjoe, D.; Zhu, B. Reducing waste management challenges: Empirical assessment of waste sorting intention among corporate employees in Ghana. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 72, 103261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juliana, N.; Lada, S.; Chekima, B.; Abdul Adis, A.A. Exploring determinants shaping recycling behavior using an extended theory of planned behavior model: An empirical study of households in Sabah, Malaysia. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, J.; Modi, A.; Patel, J. A Predicting green product consumption using theory of planned behavior and reasoned action. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 29, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergura, D.T.; Zerbini, C.; Luceri, B.; Palladino, R. Investigating sustainable consumption behaviors: A bibliometric analysis. Br. Food J. 2023, 125, 253–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hailemariam, A.; Erdiaw-Kwasie, M.O. Towards a circular economy: Implications for emission reduction and environmental sustainability. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2023, 32, 1951–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winterich, K.P.; Nenkov, G.Y.; Gonzales, G.E. Knowing what it makes: How product transformation salience increases recycling. J. Mark. 2019, 83, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erts, M.; Addar, W.; Orghemmi, C.; Takaffoli, M. Overview of factors influencing consumer engagement with plastic recycling. WIREs Energy Env. 2023, 12, e493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazen, B.T.; Mollenkopf, D.A.; Wang, Y. Remanufacturing for the circular economy: An examination of consumer switching behavior. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2017, 26, 451–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunka, A.D.; Linder, M.; Habibi, S. Determinants of consumer demand for circular economy products. A case for reuse and remanufacturing for sustainable development. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2021, 30, 535–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, J.L.; Hopkinson, P.G.; Tidridge, G. Val creation from circular economy-led closed loop supply chains: A case study of fast-moving consumer goods. Prod. Plan. Control Manag. Oper. 2018, 29, 509–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arli, D.; Badejo, A.; Carlini, J.; France, C.; Jebarajakirthy, C.; Knox, K.; Pentecost, R.; Perkins, H.; Thaichon, P.; Sarker, T.; et al. Predicting intention to recycle on the basis of the theory of planned behavior. Int. J. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Mark. 2019, 25, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Vilkaite-Vaitone, N.; Jeseviciute-Ufartiene, L. Predicting textile recycling through the lens of the theory of planned behavior. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiyane, E.; Schoeman, T. Recycling Behavior of Students at a Tertiary Institution in South Africa. In Proceedings of the 18th Johannesburg International Conference on Science, Engineering, Technology & Waste Management (SETWM-20), Johannesburg, South Africa, 16–17 November 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Danson, G.; Hancocks, J. Attitude and Practices of Consumers Towards Recycling of Household Waste in Mandela Bay. Master’s Dissertation, Nelson Mandela University, Gqeberha, South Africa, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Haywood, L.K.; Kapwata, T.; Oelofse, S.; Breetzke, G.; Wright, C.Y. Waste Disposal Practices in Low-Income Settlements of South Africa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polasi, T.; Matinise, S.; Oelofse, S. South African Municipal Waste Management Systems: Challenges and Solutions. The International Environmental Technology Centre (IETC). 2020. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Letlotlo-Polasi/publication/346025379_SOUTH_AFRICAN_MUNICIPAL_WASTE_MANAGEMENT_SYSTEMS_CHALLENGES_AND_SOLUTIONS/links/60014a7745851553a0453965/SOUTH-AFRICAN-MUNICIPAL-WASTE-MANAGEMENT-SYSTEMS-CHALLENGES-AND-SOLUTIONS.pdf (accessed on 24 February 2024).

- Helmefalk, M.; Palmquist, A.; Rosenlund, J. Understanding the mechanisms of household and stakeholder engagement in a recycling ecosystem: The SDL perspective. Waste Manag. 2023, 160, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pewa, M.K.P. Household Waste Management in a South African Township. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Hull, Hull, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Adeniran, A.A.; Shakantu, W. The health and environmental impact of plastic waste disposal in South African townships: A review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omotayo, A. Investigating the Drivers of Solid Waste Generation and Disposal: Evidence from South Africa. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijman-Ross, E.; Umutesi, J.U.; Turay, J.; Shamavu, D.; Atanga, W.A.; Ross, D. Toward a preliminary research agenda for the circular economy adoption in Africa. Front. Sustain. 2023, 4, 1061563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Averda. South African Waste Management Sector Can Still Improve. 2022. Available online: https://www.averda.com/rsa/news/south-african-waste-management-sector-can-still-improve (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Dlamini, B.R.; Rampedi, I.T.; Ifegbesan, A.P. Community Resident’s Opinions and Perceptions on the Effectiveness of Waste Management and Recycling Potential in the Umkhanyakude and Zululand District Municipalities in the KwaZulu-Natal Province of South Africa. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubanza, N.S. Analysing the challenges of solid waste management in low-income communities in South Africa: A case study of Alexandra, Johannesburg. S. Afr. Geogr. J. 2024, 107, 169–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardrop, N.; Dzodzomenyo, M.; Aryeetey, G.; Hill, A.; Bain, R.; Wright, J. Estimation of packaged water consumption and associated plastic waste production from household budget surveys. Environ. Res. Lett. 2017, 12, 074029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uche, O.L. Plastic Waste Regime in Rwanda, Kenya and South Africa: A Comparative Case Study. Am. J. Law 2023, 5, 54–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busara Global. The Plastic Predicament: Exploring Barriers and Motivators to Recycling Behaviour Change. Available online: https://busara.global/blog/the-plastic-predicament-exploring-barriers-and-motivators-to-recycling-behaviour-change/#:~:text=There%20are%20several%20infrastructural%20and%20design%20challenges%20for,reuse%20in%20both%20India%20and%20Kenya%2C%20among%20others (accessed on 24 February 2025).

- Ndukwe, V.A.; Uzoegbu, M.U.; Ndukwe, O.S.; Agibe, A.N. Environmental and health impact of solid waste disposal in Umuahia and environs, Southeast, Nigeria. J. Appl. Sci. Environ. Manag. 2019, 23, 1615–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanjrani, M.A.; Saeeda Rind, S.; Shaikh, K.H. Solid waste management: Environmental impact and solutions, specially focused to Pakistan. J. Entrep. Manag. Innov. 2023, 5, 38–67. [Google Scholar]

- Muzenda, E.; Ntuli, F.; Pilusa, T.J. Waste management, strategies and situation in South Africa: An overview. Int. J. Environ. Ecol. Eng. 2012, 6, 552–555. [Google Scholar]

- Ngonso, B.F.; Sunny-Duke, F.K.; Akpoyovwere, O.J.; Egielewa, P.E. Waste Recycling and the Nigerian Economy: Utilising Social Media for Environmental Waste Management Education. Int. J. Afr. Lang. Media Stud. (IJALMS) 2023, 3, 129–138. [Google Scholar]

- Anyaogu, I. Nigeria’s 32m-Ton Annual Solid Waste Ripe for Investments. 2022. Available online: https://businessday.ng/big-read/article/nigerias-32m-ton-annual-solid-waste-ripe-for-investments (accessed on 24 February 2025).

- Ogunseye, N.A.; Ogunseye, A.O.; Ogunseye, O.D.; Tongo, S.O.; Oladesu, J.O.; Oyinloye, M.A.; Uzzi, F.O. Leveraging Waste Recycling as a Gateway to a Green Economy in Nigeria. J. Indones. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2024, 5, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aderibige, A. The State of Recycling in Nigeria and Its Contributions to Sustainable Development. 2024. Available online: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/state-recycling-nigeria-its-contributions-sustainable-aderibigbe-5zoje/ (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- Adam, B.A.; Ahmed, A.; Abdelrhman, I.A. Health and environmental impacts due to final disposal of solid waste in Zalingy Town- Central Darfur State, Sudan. J. Res. 2016, 4, 2394–3629. [Google Scholar]

- Midika, E.S. Factors Influencing Recycling of Solid Waste in Machakos County, Kenya. PhD. Thesis, University of Nairobi, Nairobi, Kenya, 2016; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Amugsi Muindi, K.; Mberu, B.U. Implementation of solid waste management policies in Kenya: Challenges and opportunities. Cities Health 2022, 6, 528–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debrah, J.K.; Teye, G.K.; Dinis, M.A.P. Barriers and Challenges to Waste Management Hindering the Circular Economy in Sub-Saharan Africa. Urban Sci. 2022, 6, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbiro Muiruri, J.M.; Wahome, R.; Karatu, K. Study of Residents’ Attitude and Knowledge on Management of Solid Waste in Eastleigh, Nairobi, Kenya. J. Environ. Prot. 2020, 11, 779–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugambe, R.K.; Nuwematsiko, R.; Ssekamatte, T.; Nkurunziza, A.G.; Wagaba, B.; Isunju, J.B.; Wafula, S.T.; Nabaasa, H.; Katongole, C.B.; Atuyambe, L.M.; et al. Drivers of Solid Waste Segregation and Recycling in Kampala Slums, Uganda: A Qualitative Exploration Using the Behavior Centered Design Model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sekhampu, T.J. Determinants of poverty in a South African township. J. Soc. Sci. 2013, 34, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngeleka, P.S. An Investigation into Solid Waste Management in Townships: The Case Study of Clermont, Kwa-Zulu Natal. Master’s Thesis, University of KwaZulu-Natl, Durban, South Africa, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Rasmeni, Z.Z.; Madyira, D.M. A review of the current municipal solid waste management practices in Johannesburg City townships. Procedia Manuf. 2019, 35, 1025–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, P. Cities of Gold, Townships of Coal: Essays on South Africa’s New Urban Crisis; Africa World Press: Trenton, NJ, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Jürgens, U.; Donaldson, R.; Rule, J.; Bäh, J. Townships in South African cities: Literature review and research perspectives. Habitat Int. 2013, 39, 256–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govender, T.; Barnes, J.M.; Pieper, C.H. Contribution of water pollution from inadequate sanitation and housing quality to diarrheal disease in low-cost housing settlements of Cape Town, South Africa. Am. J. Public Health 2011, 101, e4–e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwan, A. Recycling: Why Do South Africans Care So Little About It. 2023. Available online: https://www.thesouthafrican.com/news/www-thesouthafrican-news-recycling-is-not-on-our-minds-03-may-2023/ (accessed on 4 February 2024).

- Mbambo, S.B.; Agbola, S.B. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Townships and Lessons for Urban Spatial Restructuring in South Africa. Afr. J. Gov. Dev. 2020, 9, 331–335. [Google Scholar]

- Mngomezulu, S.K.; Mbanga, S.; Adeniran, A.A.; Soyez, K. Factors influencing solid waste management practices in Joe Slovo Township, Nelson Mandela Bay. J. Public Admin. 2020, 55, 400–411. [Google Scholar]

- Matete, N.; Trois, C. Towards zero waste in emerging countries—A South African experience. Waste Manag. 2008, 28, 1480–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, M. Campus sustainability: An integrated model of college students’ recycling behavior on campus. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2019, 20, 1042–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Liu, P. Exploring waste separation using an extended theory of planned behavior: A comparison between adults and children. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1337969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuriev, A.; Dahmen, M.; Paillé, P.; Boiral, O.; Guillaumie, L. Pro-environmental behaviors through the lens of the theory of planned behavior: A scoping review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 155, 104660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.H.; Nguyen, T.H.; Mai, L.H.; Nguyen, T.T.P.; Nguyen, T.M.L.; Nguyen, T.P.L. The factors affecting Vietnamese people’s sustainable tourism intention: An empirical study with extended the theory of planned behavior (TPB). Foresight J. 2023, 25, 844–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, R.; Galati, A.; Schifani, G.; Di Trapani, A.M.; Migliore, G. Culinary tourism experiences in agri-tourism destinations and sustainable consumption: Understanding Italian tourists’ motivations. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Ye, J. Determinants of consumers’ apparel recycling behavior intention using the extended norm activation model and the theory of planned behavior: An empirical study from China. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Meng, B.; Kim, W. Emerging bicycle tourism and the theory of planned behavior. J. Sustain. Tour. 2016, 25, 292–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, L.-Y.; Hew, T.-S.; Ooi, K.-B.; Metri, B.; Dwivedi, Y.K. Extending the Theory of Planned Behavior in the Social Commerce Context: A Meta-Analytic SEM (MASEM) Approach. Inf. Syst. Front. 2023, 25, 1847–1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Toit, J.L.; Wagner, C.; Fletcher, L. Socio-spatial factors affecting household recycling in townhouses in Pretoria, South Africa. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camilleri, A.P.; Ferrari, J.R. Agency or Structure? Community and Individual Level factors impacting Recycling Behaviors. Glob. J. Community Psychol. Pract. 2024, 15, 1–16. Available online: https://www.gjcpp.org/ (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Aboelmaged, M. E-waste recycling behaviour: An integration of recycling habits into the theory of planned behaviour. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 278, 124182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Yang, J.Z.; Clark, S.S.; Shelly, M.S. Recycling as a planned behavior: The moderating role of perceived behavioral control. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 24, 11011–11026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boakye, M.K.; Adanu, S.K.; Agbosu, W.K.; Lissah, S.Y.; Owusu, A.G. Behavioral factors influencing the acceptance and usage of waste bins in Ghana: Application of the extended theory of planned behavior (TPB). Manag. Environ. Qual. 2024, 35, 986–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhassan, H.; Asante, F.A.; Oteng-Ababio, M.; Bawakyillenuo, S. Application of theory of planned behaviour to households’ source separation behaviour in Ghana. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2018, 29, 704–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eremionkhale, G.E.; Sekhon, H.; Lazell, J.; Spiteri-Cornish, L. The Role of An Augmented Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) On Recycling Behaviours in Lagos Nigeria. In Proceedings of the 22nd European Conference on Knowledge Management, ECKM 2021, Coventry, UK, 2–3 September 2021; Garcia-Perez, A., Simkin, L., Eds.; Academic Conferences International Limited: Oxfordshire, UK, 2021; pp. 905–914. [Google Scholar]

- Vijayan, R.V.; Krishnan, M.M.; Parayitam, S.; Duraisami, S.P.A.; Saravanaselvan, N.R. Exploring e-waste recycling behaviour intention among the households: Evidence from India. Clean. Mater. 2023, 7, 100174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, T. The Role of Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) Explaining Recycling Behavior: An Emerging Market Perspective. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. Res. 2021, 6, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njoku, A.; Mouloudj, K.; Bouarar, A.C.; Evans, M.A.; Asanza, D.M.; Mouloudj, S.; Bouarar, A. Intentions to Create Green Start-Ups for Collection of Unwanted Drugs: An Empirical Study. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Qin, S.; Gou, Z.; Yi, M. Can green building promote pro-environmental behaviors? The psychological model and design strategy. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koshta, N.; Patra, S.; Prakash, S. Sharing economic responsibility: Assessing end user’s willingness to support E-waste reverse logistics for circular economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 332, 130057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oke, A.; McDonald, S.; Korobilis-Magas, E.; Osobajo, O.A.; Awuzie, B.O. Reframing recycling behavior through consumers’ perceptions: An exploratory investigation. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodie, R.J.; Ilic, A.; Juric, B.; Hollebeek, L. Consumer engagement in a virtual brand community: An exploratory analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollebeek, L.D.; Juric, B.; Tang, W. Virtual brand community engagement practices: A refined typology and model. J. Serv. Mark. 2017, 31, 204–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollenbeck, C.R.; Kaikati, A.M. Consumers’ use of brands to reflect their actual and ideal selves on Facebook. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2012, 29, 395–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langaro, D.; Rita, P.; Salgiro, M. Do social networking sites contribute for building brands? Evaluating the impact of users’ participation on brand awareness and brand attitude. J. Mark. Commun. 2018, 24, 146–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dessart, L. Social media engagement: A model of antecedents and relational outcomes. J. Mark. Manag. 2017, 33, 375–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, A.; Bairrada, C.; Peres, F. Brand communities’ relational outcomes, through brand love. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2019, 28, 154–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldus, B.J.; Voorhees, C.; Calantone, R. Online brand community engagement: Scale development and validation. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 68, 978–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dessart, L.; Veloutsou, C.; Morgan-Thomas, A. Consumer engagement in online brand communities: A social media perspective. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2015, 24, 28–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calder, B.J.; Malthouse, E.C.; Schaedel, U. An experimental study of the relationship between online engagement and advertising effectiveness. J. Interact. Mark. 2009, 23, 321–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eigenraam, A.W.; Eelen, J.; van Lin, A.; Verlegh, P.W.J. A consumer-based taxonomy of digital customer engagement practices. J. Interact. Mark. 2018, 44, 102–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollebeek, L.D.; Glynn, M.S.; Brodie, R.J. Consumer brand engagement in social media: Conceptualization, scale development and validation. J. Interact. Mark. 2014, 28, 149–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodie, R.J.; Hollebeek, L.D.; Jurić, B.; Ilić, A. Customer engagement: Conceptual domain, fundamental propositions, and implications for research. J. Serv. Res. 2011, 14, 252–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaakkola, E.; Alexander, M. Role of customer engagement behavior in val co-creation: A service system perspective. J. Serv. Res. 2014, 17, 247–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boldero, J. The prediction of household recycling of newspapers: The role of attitudes, intentions, and situational factors. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 25, 440–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, W.; Guan, Y. A joint use of energy evaluation, carbon footprint and economic analysis for sustainability assessment of grain system in China during 2000–2015. J. Integr. Agric. 2018, 17, 2822–2835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Tan, X.; Wang, Y.; Wen, Z.; Tao, Y.; Qian, Y. Investigation on decision-making mechanism of residents’ household solid waste classification and recycling behaviors. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 140, 224–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, B.; Yang, W.; Shen, X. A comparison study of ‘motivation–intention–behavior’ model on household solid waste sorting in China and Singapore. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 211, 442–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schanes, K.; Dobernig, K.; Gozet, B. Food waste matters: A systematic review of household food waste practices and their policy implications. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 182, 978–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodard, R.; Rossouw, A. Increasing recycling through effective resident engagement at multiple occupancy housing developments: The waste its mine its your project. In ISWA 2015 World Congress Antwerp; Vereniging van Vlaamse Steden en Gemeenten vzw: Brussels, Belgium, 2015; pp. 450–460. [Google Scholar]

- Hameed, I.; Khan, K.; Waris, I.; Zainab, B. Factors influencing the sustainable consumer behavior concerning the recycling of plastic waste. Env. Qual Manag. 2022, 32, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, S.; Ahmad, A.; Madsen, D.Ø.; Sohail, S.S. Sustainable behavior with respect to managing e-wastes: Factors influencing e-waste management among young consumers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofstad, S.P.; Tobolova, M.; Nayum, A.; Klöckner, C.A. Understanding the mechanisms behind changing people’s recycling behavior at work by applying a comprehensive action determination model. Sustainability 2017, 9, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razali, F.; Daud, D.; Weng-Wai, C.; Jiram, W.R.A. Waste separation at source behavior among Malaysian households: The theory of planned behavior with moral norm. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 271, 122025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabbir, M.; Raziuddin Taufiq, R.; Nomi, M. Consumers’ reverse exchange behavior and e-waste recycling to promote sustainable post-consumption behavior. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2023, 35, 2484–2500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakpour, A.H.; Zeidi, I.M.; Emamjomeh, M.M.; Asefzadeh, S.; Pearson, H. Household waste behaviors among a community sample in Iran: An application of the theory of planned behavior. Waste Manag. 2014, 34, 980–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, L.; Bishop, B.A. Moral basis for recycling: Extending the theory of planned behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 36, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, C.; Cheung, R.; Shen, G.Q. Recycling attitude and behavior in university campus: A case study in Hong Kong. Facilities 2012, 30, 630–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, B.; Ge, J. What affects consumers’ intention to recycle retired EV batteries in China? J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 359, 132065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A. Exploring young adults’ e-waste recycling behavior using an extended theory of planned behavior model: A cross-cultural study. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 141, 378–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.; Ahmed, W.; Najmi, A. Understanding consumers’ behavior intentions towards dealing with the plastic waste: Perspective of a developing country. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 142, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khare, A. Antecedents to green buying behavior: A study on consumers in an emerging economy. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2015, 33, 309–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hsu, L.T.; Sheu, C. Application of the theory of planned behavior to green hotel choice: Testing the effect of environmentally friendly activities. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, W.-T.; Huang, M.-H.; Cheng, B.-Y.; Chiu, R.-J.; Chiang, Y.-T.; Hsu, C.-W.; Ng, E. Applying a comprehensive action determination model to examine the recycling behavior of Taipei city residents. Sustainability 2021, 13, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholamrezai, S.; Aliabadi, V.; Ataei, P. Understanding the pro-environmental behavior among green poultry farmers: Application of behavioral theories. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 16100–16118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, J.; Zhao, S.; Yang, S. Information publicity and resident’s waste separation behavior: An empirical study based on the norm activation model. Waste Manag. 2019, 87, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberg, S.; Moser, G. Twenty years after Hines, Hungerford, and Tomera: A new meta-analysis of psycho-social determinants of pro-environmental behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 2007, 27, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. Normative influences on altruism. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1977, 10, 221–279. [Google Scholar]

- Moser, A.K. Thinking green, buying green? Drivers of pro-environmental purchasing behavior. J. Consum. Mark. 2015, 32, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Fan, J.; Zhao, D. Predicting household PM2.5-reduction behavior in Chinese urban areas: An integrative model of theory of planned behavior and norm activation theory. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 145, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botetzagias, I.; Dima, A.F.; Malesios, C. Extending the theory of planned behavior in the context of recycling: The role of moral norms and of demographic predictors. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2015, 95, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Cai, L.; Yn, K.F.; Wang, X. Exploring consumers’ usage intention of reusable express packaging: An extended norm activation model. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 72, 103265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Zhan, W. How to activate moral norm to adopt electric vehicles in China? An empirical study based on extended norm activation theory. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 3546–3556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Werff, E.; Steg, L. One model to predict them all: Predicting energy behaviors with the norm activation model. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2015, 6, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triandis, C.H. Interpersonal Behavior; Brooks/Cole Pub. Co.: Monterey, CA, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, B.; Lally, P.; Rebar, A.L. Does habit weaken the relationship between intention and behavior? Revisiting the habit-intention interaction hypothesis. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2020, 14, e12553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, B.-Y.; Rahim, M.A. Socio-Behavioral Study of Home Computer Users’ Intention to Practice Security. 2005, pp. 234–247. Available online: https://aisel.aisnet.org/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1132&context=pacis2005 (accessed on 10 November 2024).

- Ibrahim, A.; Knox, K.; Rundle-Thiele, S.; Arli, D. Segmenting a water use market: Theory of interpersonal behavior insights. Soc. Mark. Q. 2018, 24, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertz, M.; Huang, R.; Jo, M.S.; Karakas, F.; Sarigöllü, E. From single use to multi-use: Study of consumers’ behavior toward consumption of reusable containers. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 193, 334–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J. Triandis’ Theory of Interpersonal Behavior in Understanding Software Piracy Behavior in the South African Context. Master’s Thesis, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Linder, N.; Rosenthal, S.; Sörqvist, P.; Barthel, S. Internal and external factors’ influence on recycling: Insights from a laboratory experiment with observed behavior. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 699410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bervell, B.; Kumar, J.A.; Arkorful, V.; Agyapong, E.M.; Osman, S. Remodelling the role of facilitating conditions for Google Classroom acceptance: A revision of UTAUT2. Australas. J. Educ. Technol. 2021, 38, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, M.S.; Abdullah, S.H.; Abd Manaf, L.; Sharaai, A.H.; Nabegu, A.B. Examining the moderating role of perceived lack of facilitating conditions on household recycling intention in Kano, Nigeria. Recycling 2024, 2, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meena, R.; Sarabhai, S. Extrinsic motivators driving adults purchase intention on mobile apps: The mediating role of self-efficacy and facilitating conditions. J. Mark. Commun. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-K.; Kim, S.; Kim, M.-S.; Choi, J.-G. Antecedents and interrelationships of three types of pro-environmental behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 2097–2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlap, R.; Jones, R. Environmental Concern: Conceptual and Measurement Isss. In Handbook of Environmental Sociology; Dunlap, R., Michelson., W., Eds.; Greenwood: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann, P.; Apaolaza-Ibáñez, V. Consumer attitude and purchase intention toward green energy brands: The roles of psychological benefits and environmental concern. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 1254–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Fan, J.; Zhao, D.; Yang, S.; Fu, Y. Predicting consumers’ intention to adopt hybrid electric vehicles: Using an extended version of the theory of planned behavior model. Transportation 2016, 43, 123–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koklic, M.K.; Golob, U.; Podnar, K.; Zabkar, V. The interplay of past consumption, attitudes and personal norms in organic food buying. Appetite 2019, 137, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotyza, P.; Cabelkova, I.; Pierański, B.; Malec, K.; Borusiak, B.; Smutka, L.; Nagy, S.; Gawel, A.; Bernardo López Lluch, D.; Kis, K.; et al. The predictive power of environmental concern perceived behavioral control and social norms in shaping pro-environmental intentions: A multicountry study. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2024, 12, 1289139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borusiak, B.; Szymkowiak, A.; Horska, E.; Raszka, N.; Żelichowska, E. Towards building sustainable consumption: A study of second-hand buying intentions. Sustainability 2020, 12, 875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salimi, M. Effects of environmental concerns and green knowledge on green product consumptions with an emphasis on mediating role of perceived behavioral control, perceived val, attitude, and subjective norm. Int. Trans. J. Eng. Manag. Appl. Sci. Technol. 2019, 10, 651–661. [Google Scholar]

- Cilliers, J.O. High inventory levels: The raison d’être of township retailers. S. Afr. J. Econ. Manag. Sci. 2018, 21, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boomsma, A. The robustness of maximum likelihood estimation in structural equation models. In Structural Modelling by Example; Cuttance, P., Ecob, R., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1987; pp. 160–188. [Google Scholar]

- Shukla, S.A. Study on millennial purchase intention of green products in India: Applying extended theory of planned behavior model. J. Asia Pac. Bus. 2019, 20, 322–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarty, J.A.; Shrum, L.J. The recycling of solid wastes: Personal values, value orientations, and attitudes about recycling as antecedents of recycling behavior. J. Bus. Res. 1994, 30, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Zhu, Y.; Zhai, J. Understanding waste management behavior among university students in China: Environmental knowledge, personal norms, and the theory of planned behavior. Front. Psychol. 2022, 12, 771723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobbelstein, T.; Lochner, C. Factors influencing purchase intention for recycled products: A comparative analysis of Germany and South Africa. Sustain. Dev. 2023, 31, 2256–2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iriyadi, S.B.; Puspitasari, R. Consumer intentions to reduce food waste in all-you-can-eat restaurants based on personal norm activation. Heliyon 2023, 9, e13399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, B.; Lee, J. Household waste separation intention and the importance of public policy. Int. Trade Politics Dev. 2020, 4, 61–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P. Theory of Planned Behavior Approach to Understand the Purchasing Behavior for Environmentally Sustainable Products; Working Paper Series No. 2012-12-08; Indian Institute of Management: Ahmedabad, India, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modelling; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Nachtigall, C.; Kroehne, U.; Funke, F.; Steyer, R. (Why) Should We Use SEM? Pros and Cons of Structural Equation Modeling. Methods Psychol. Res. Online 2003, 8, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.; Black, W.; Babin, B.; Anderson, R.; Tatham, R. Multivariate Data Analysis, 6th ed.; Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis, 8th ed.; Pearson Prentice: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis, 5th ed.; Prentice-Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra, N.K. Marketing Research: An applied Orientation, 7th ed.; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Tiew, K.G.; Basri, N.E.A.; Deng, H.; Watanabe, K.; Zain, S.T. Comparative study on recycling behaviors between regular recyclers and non-regular recyclers in Malaysia. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 237, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Leeuw, A.; Valois, P.; Ajzen, I.; Schmidt, P. Using the theory of planned behavior to identify key beliefs underlying pro-environmental behavior in high-school students: Implications for educational interventions. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 42, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopper, J.R.; Nielsen, J.M. Recycling as altruistic behavior: Normative and behavioral strategies to expand participation in a community recycling program. Environ. Behav. 1991, 23, 195–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, R.; Nigg, C.R. Advancing Physical Activity Theory: A Review and Future Directions. Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev. 2011, 39, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taufiq, K.M.R.; Vaithianathan, S.A. A fresh look at understanding green consumer behavior among young urban indian consumers through the lens of theory of planned behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 183, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, S.; Badgaiyan, A.J. Towards improved understanding of reverse logistics-examining mediating role of return intention. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2016, 107, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Grange, L. The Governance Role of Local Government in the Recycling of Domestic Waste. Ph.D. Thesis, North-West University, Potchefstroom, South Africa, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Godfrey, L.; Oelofse, S. A Systems Approach to Waste Governance—Unpacking the Challenges Facing Local Government. 2017. Available online: https://researchspace.csir.co.za/server/api/core/bitstreams/a84ae71b-c427-4394-acf1-668d11295d94/content (accessed on 20 February 2025).

| Criterion | Val | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 275 | 66.9% |

| Female | 136 | 33.1% | |

| Total | 411 | 100.0% | |

| Age | 18–24 years | 116 | 28.2% |

| 25–29 years | 111 | 27.0% | |

| 30–40 years | 145 | 35.3% | |

| 41–50 years | 28 | 6.8% | |

| 51–59 | 7 | 1.7% | |

| 60+ | 4 | 1.0% | |

| Total | 411 | 100.0% | |

| Marital status | Married | 96 | 23.4% |

| Unmarried | 315 | 76.6% | |

| Total | 411 | 100.0% | |

| Level of education | Did not complete high school | 11 | 2.7% |

| Completed Grade 12/matric | 154 | 37.5% | |

| Completed short courses | 25 | 6.1% | |

| Post-school qualification—diploma or certificate | 119 | 29.0% | |

| Post-school qualification—degree | 102 | 24.8% | |

| Total | 411 | 100.0% | |

| Income | R0–R2500 [$132] | 103 | 25.1% |

| R2501 [$132]–R5000 [$264] | 69 | 16.8% | |

| R5001 [$264]–R7500 [$397] | 68 | 16.5% | |

| R7501 [$397]–R12,500 [$661] | 64 | 15.6% | |

| R12,501 [$661]–R20,000 [$1058] | 65 | 15.8% | |

| More than R20,000 [$1058] | 42 | 10.2% | |

| Total | 411 | 100.0% |

| Indices | CMIN | df | CMIN/df | GFI | NFI | TLI | CFI | RMSEA | SRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Values | 509.49 | 247 | 2.063 | 0.91 | 0.93 | 0.95 | 0.96 | 0.051 | 0.046 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Makhitha, K.M. South African Township Consumers’ Recycling Engagement and Their Actual Recycling Behavior. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4570. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104570

Makhitha KM. South African Township Consumers’ Recycling Engagement and Their Actual Recycling Behavior. Sustainability. 2025; 17(10):4570. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104570

Chicago/Turabian StyleMakhitha, Kkathutshelo Mercy. 2025. "South African Township Consumers’ Recycling Engagement and Their Actual Recycling Behavior" Sustainability 17, no. 10: 4570. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104570

APA StyleMakhitha, K. M. (2025). South African Township Consumers’ Recycling Engagement and Their Actual Recycling Behavior. Sustainability, 17(10), 4570. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104570