1. Introduction

Family firms, characterized by significant family influence over ownership, control, or management and active involvement of family members in corporate governance and strategic decision-making [

1], represent one of the oldest and most prevalent forms of business organization [

2]. They are widely distributed across the globe, accounting for approximately 90% of all enterprises and contributing over 70% of global GDP, thus playing a pivotal role in the world economy [

3]. On the one hand, due to the dominance of kinship-based ownership, family firms tend to prioritize socioemotional wealth and pursue harmonious coexistence with local communities, placing greater emphasis on green development strategies compared with non-family firms [

4,

5,

6,

7]. On the other hand, influenced by intergenerational succession and traditional business models, family firms often exhibit strong path dependence, conservative management styles, and a pronounced aversion to risk [

8]. According to a 2022 report jointly released by the CEIBS Family Heritage Research Center and Family Business magazine, R&D investment in Chinese family firms is significantly lower than in non-family firms, and this gap continues to widen [

9]. This presents a paradox: although family firms tend to be more environmentally conscious, their conservative approach to R&D results in underinvestment, which may hinder their green innovation capacity and long-term sustainable development.

To address the innovation challenges faced by family firms and compensate for their insufficient R&D input, the government often provides financial subsidies, commonly referred to as government grants [

10]. Existing studies have examined the effects of government subsidies on corporate innovation from various perspectives, such as risk tolerance, innovation quality and quantity, firm size, and market competition [

11]. Many scholars find a “U-shaped” relationship between subsidies and innovation, where the effectiveness of subsidies initially declines before improving [

12,

13]. Other studies suggest that government subsidies typically stimulate only short-term R&D investment and have limited long-term effects [

14]. In recent years, governments have introduced green subsidies specifically targeting corporate investment in green innovation. As a form of environmental regulation, green subsidies provide financial and material support for green innovation, partially alleviating the funding constraints that hinder such efforts in family firms [

15,

16].

Beyond direct financial support, governments also implement broader economic policies to foster enterprise development [

17]. In theory, such policies enhance resource allocation efficiency and improve market performance [

18]. However, in practice, frequent and short-term policy adjustments may increase economic policy uncertainty (EPU), making it difficult for firms to anticipate policy changes [

19]. External influencing factors may have a significant impact on enterprises and even lead them into difficulties [

20]. As a result, firms may become more cautious in their production and investment decisions [

21]. Studies have shown that heightened EPU adversely affects investment, employment [

22], and productivity, weakens bank liquidity creation, and increases household savings [

23], thereby reducing both firms’ financing capacity and market demand. For enterprises, elevated EPU increases external risk exposure, discourages high-risk investments, and raises financing costs due to more conservative lending behavior by banks [

24]. Given the high adjustment costs and long-term capital commitment associated with innovation activities, heightened policy uncertainty may further increase market volatility expectations, leading firms to reduce green innovation investment [

25].

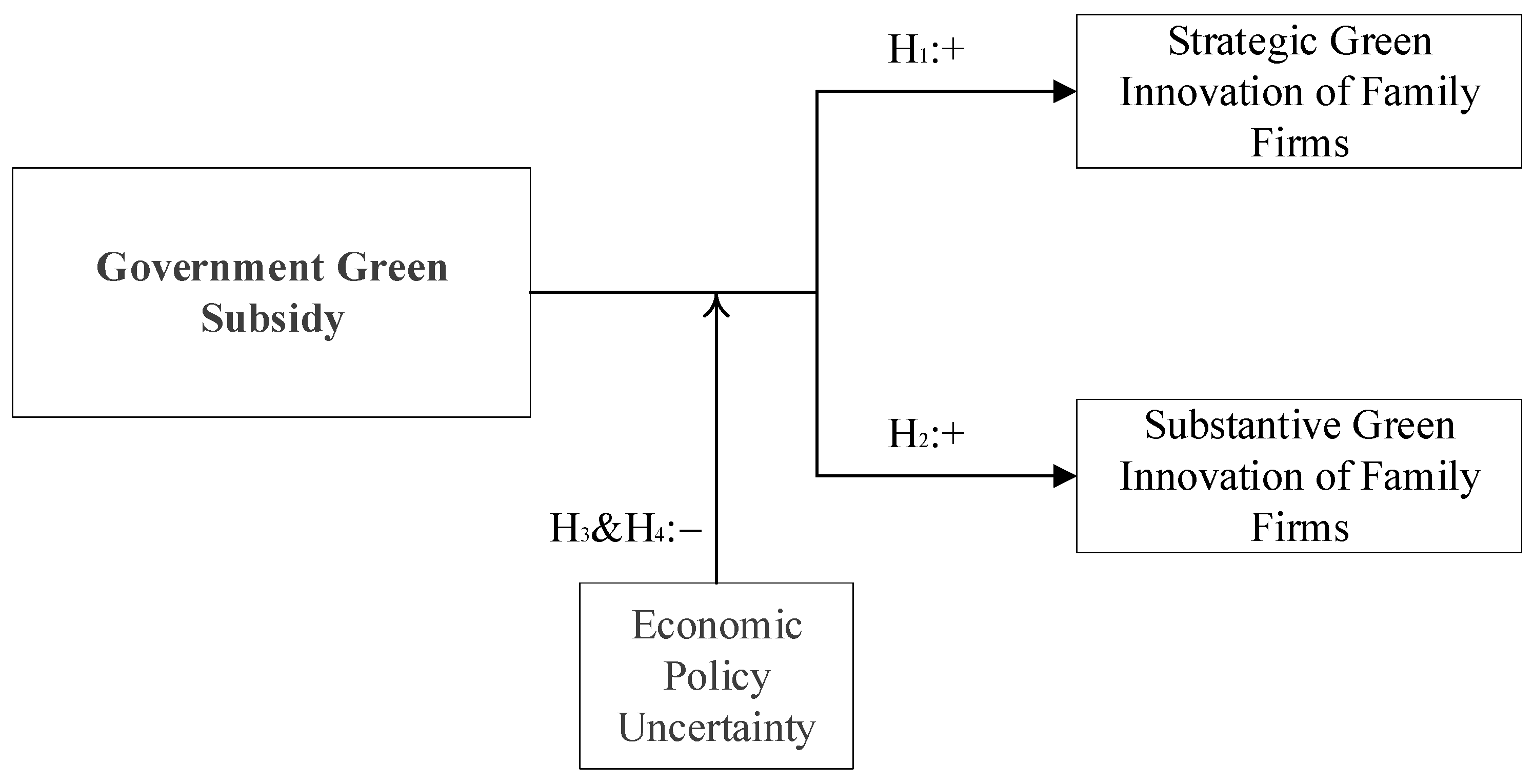

Based on the above literature and theoretical insights, both government green subsidies and economic policy uncertainty are likely to influence green innovation in family firms. However, how these factors exert their influence and under what conditions remains insufficiently explored. Despite growing attention to the role of government subsidies in stimulating innovation, existing research presents several limitations. First, most studies focus on the overall or technological innovation effects of subsidies, without distinguishing between strategic green innovation and substantive green innovation, which are driven by different motivations and entail different implications [

13]. This limits our understanding of the heterogeneous impact mechanisms. Second, while some studies have investigated the endogenous drivers of green innovation in family firms (e.g., family identity [

26], culture [

27], and succession [

4,

28]), relatively little attention has been paid to the role of external policy incentives—particularly green subsidies—in shaping innovation behaviors in family firms. Third, current studies are largely based on general firm samples, with limited research specifically targeting the unique governance structures and socioemotional priorities of family firms [

29], thereby overlooking their dual “emotional–rational” logic in innovation decision-making.

This study aims to make several marginal contributions. First, it theoretically and empirically investigates the role of government green subsidies as an external resource in influencing R&D input and green innovation in family firms. By distinguishing between strategic and substantive green innovation, it enriches the theoretical understanding of how public policy instruments affect different types of innovation outcomes. Second, while economic policy uncertainty has been widely recognized as an important external environmental factor affecting business decisions, its moderating effect on the relationship between government subsidies and green innovation in family firms remains underexplored. Considering that EPU often originates from government behavior itself, understanding its influence on subsidy effectiveness is both theoretically and practically significant. By incorporating EPU as a moderator, this study not only extends the application of policy uncertainty research but also provides useful insights for improving the design and implementation of green subsidy policies.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 reviews the relevant literature and presents the theoretical framework and hypotheses.

Section 3 describes the research design.

Section 4 reports the empirical results.

Section 5 provides further analysis.

Section 6 concludes and discusses policy implications.

3. Date and Research Method

3.1. Data Source

This study employs panel data from A-share listed family enterprises between 2008 and 2022, following the implementation of new accounting standards in 2007. The green patent application data are sourced from CNRDS, the economic policy uncertainty index is obtained from the economic policy uncertainty website, and other relevant data are derived from the CSMAR database. After integrating the data, the sample data of ST and *ST are excluded, and finally, 8138 sample data are formed.

3.2. Model Specification and Variable Explanation

Given the continuous nature of the dependent variables and the objective of estimating linear relationships, ordinary least squares (OLS) regression is adopted as the primary estimation method. To test the above hypotheses, the following OLS models are constructed for empirical analysis:

Among them, Models (1) and (2) are used to verify hypotheses H1 and H2, and Models (3) and (4) are used to verify hypotheses H3 and H4. All the empirical work was carried out in Stata 17.0.

In the model, “i” represents the ID of the listed company, “t” represents the year, “DM” represents the industry classification, and “Control” represents the control variable. The specific measurement methods of the variables are shown in

Table 1.

Dependent variables: strategic green innovation (GN) and substantive green innovation (GI). GNi,t and GIi,t represent the strategic green innovation and substantive green innovation of family enterprise “i” in year “t”, respectively. According to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, we defined green patents as follows: the number of green invention patent applications is used as an indicator of substantive green innovation, and the number of green new utility patent applications of family firms is used as an indicator of strategic green innovation. During processing, 1 was added to the number of green patent applications, and then the logarithm was taken.

Explanatory Variable: Gresub represents the government green subsidy obtained by family firms in the current year. Referring to the research of Zhang et al. (2024) [

48], based on the specifics of government subsidy items detailed in the footnotes of annual financial reports, this study identifies and extracts annual green subsidy amounts through keyword searches. Specifically, we systematically examine the disclosures related to government subsidies in the notes to financial statements, screening subsidy items by applying carefully selected keywords, including but not limited to “environmental protection subsidy”, “green”, “energy conservation”, “emission reduction”, “clean production”, “low-carbon”, and “environment”. Items explicitly matching these keywords or clearly associated with green innovation objectives are categorized as green subsidies. Subsequently, we aggregate the amounts of these identified green subsidies and compute their ratio-to-firm size to construct a standardized indicator that accurately reflects the intensity of government green innovation subsidies received by each firm.

Moderating variable: EPU represents economic policy uncertainty. According to the index proposed by Baker (2016) [

59], which is compiled by searching relevant words such as “economy”, “policy”, and “uncertainty” in mainstream media newspapers, this study converts the Chinese monthly EPU index into annual data by the arithmetic average method, and the data source is the EPU website. The increase in EPU will lead to an increase in the external risks of family enterprises, thus affecting their investment decisions, including green innovation. Gresub×EPU is the cross-term of economic policy uncertainty and government subsidy intensity, which is used as the test index to examine the moderating effect, which we have discussed in the hypotheses H3 and H4.

Control variables: The green innovation activities of family firms are influenced by a multitude of factors. To explore the possible influencing factors, enterprise scale, ownership concentration, separation rate of ownership and control rights, ownership balance degree, asset–liability ratio, Tobin’s Q value, return on invested capital, and operating income growth rate are used as control variables.

LNSIZE represents enterprise scale. Generally speaking, large family enterprises are more likely to have more funds, technology, and R&D capabilities. OS represents ownership concentration. The ownership structure is an important issue in modern corporate governance. Concentrated ownership can reflect the will of major shareholders and thus affect the green innovation intention of family enterprises. TW represents the separation rate of ownership and control rights. A higher separation rate means a larger gap between the ownership and control rights of family enterprises, which may lead to principal–agent problems, but excellent managers may also avoid the short-sightedness caused by family control. BA represents the ownership balance degree. A higher ownership balance degree can enable more democratic and transparent decision-making, thus providing a better support environment for green innovation. Asslib represents the asset–liability ratio. A lower asset–liability ratio means that the enterprise has a better financial situation and is more likely to have flexible funds for the R&D of green innovation. TBQ is Tobin’s Q value, which reflects the market’s expectation of the future profitability of the enterprise. Thus, a higher Tobin’s Q value is associated with a greater likelihood of family enterprises engaging in green innovation. Operating represents the operating income growth rate. A greater operational income growth rate suggests that the firm has performed well in the marketplace, which gives family firms more chances to implement green innovation.

Dummy variables: DM represents industry classification and is used for industry-fixed effects. Year represents the year and is used for year-fixed effects. “i” and “t” represents the random error.

3.3. Descriptive Statistics

Table 2 reports the descriptive statistics of the main variables. Regarding the dependent variables, the mean of strategic green innovation (GN) is 0.202 with a standard deviation of 0.545, and the median is 0, indicating that most firms in the sample did not apply for green utility model patents in a given year. Only a small portion of firms exhibit relatively active strategic green innovation. For substantive green innovation (GI), the mean is 0.193 with a standard deviation of 0.548, and the median is also 0, similar to GN. This suggests that green invention patent applications also exhibit high dispersion and a zero-inflated distribution, reflecting a generally low level of green innovation activities among family firms.

As for the independent variable, the mean of government green subsidies (Gresub) is 0.025, with a maximum of 0.668, a minimum of 0, and a median of 0. This indicates that the majority of firms did not receive green subsidies, and among those that did, the amounts varied considerably. This reflects the uneven distribution and limited coverage of green subsidy policies among family firms, suggesting room for further policy optimization. Cross-checking with the previous literature reveals that the descriptive results of other variables are largely consistent, indicating that the sample data are suitable for subsequent empirical analysis.

5. Further Analysis

5.1. The Mediating Effect of R&D Investment

As a direct form of fiscal support provided by the government, green subsidies not only enhance firms’ disposable resources but may also indirectly influence green innovation by guiding firms to increase their R&D investment. Building on the baseline analysis, this study further explores the potential mediating role of R&D investment in the relationship between government green subsidies and green innovation in family firms.

Specifically, based on incentive theory, firms often respond to government subsidies with short-term innovation activities in order to grow quickly and qualify for additional policy support. Prior research suggests that such subsidies can stimulate immediate innovation responses [

48]. In the case of strategic green innovation, although the technological threshold is relatively low, firms often seek to rapidly increase the number of green patents or meet regulatory requirements to achieve short-term objectives. Upon receiving green subsidies, firms may allocate a portion of resources to R&D departments to accelerate the production of patentable outcomes aligned with policy targets. In contrast, substantive green innovation typically involves higher innovation intensity and longer development cycles. For family firms, which tend to operate with concentrated resource allocation, funding constraints are a critical limiting factor. Government subsidies partially relieve pressure on R&D resources, enabling firms to undertake high-cost, long-term green innovation projects [

38]. Thus, after receiving green subsidies, firms—motivated by the pursuit of long-term competitive advantage and market expansion—are likely to increase investment in high-risk, high-tech R&D activities, which in turn drives substantive innovation [

69].

To test whether government green subsidies affect family firms’ green innovation through increased R&D investment, this study adopts the three-step regression approach proposed by Baron and Kenny (1986) [

70], and constructs the following mediation models:

Here, RDi,t represents the R&D investment of firm i in year t, and other variables are defined as previously described.

The mediation results are reported in

Table 6. Regarding substantive green innovation, the total effect of government green subsidies is significantly positive, with a coefficient of 0.3505 (

p < 0.01), indicating that green subsidies directly enhance the level of substantive green innovation in family firms. In the second step, the coefficient of government green subsidies on R&D investment is also significantly positive at 3.1934, suggesting that subsidies effectively alleviate funding constraints in high-intensity innovation activities. In the third step, when both government subsidies and R&D investment are included in the model, R&D investment is significantly positively associated with substantive green innovation (coefficient = 0.00678,

p < 0.01), and the coefficient for green subsidies remains significant, increasing from 0.3505 to 0.4348. These results indicate the presence of a stable direct effect along with partial mediation through R&D investment.

Furthermore, the analysis examines whether government green subsidies affect strategic green innovation through increased R&D investment. The results show that government subsidies have a significant and positive direct effect on strategic green innovation, with a coefficient of 0.3294 (p < 0.01), confirming that subsidies effectively incentivize rapid, policy-driven innovation among family firms. The positive impact of green subsidies on R&D investment remains consistent (coefficient = 3.1934, p < 0.01). When both variables are included in the model, R&D investment remains significantly positively associated with strategic green innovation (coefficient = 0.00457, p < 0.01), and the coefficient of government subsidies slightly increases from 0.3294 to 0.3447, remaining highly significant.

These results suggest that, in addition to a direct incentive effect, government green subsidies also indirectly promote firms’ engagement in rapid, compliance-oriented green patent applications through increased R&D input, thereby forming a mediating transmission channel.

5.2. Heterogeneity in Pollution Degree

Given that heavily polluting enterprises are typically subject to more stringent environmental regulations and greater policy pressure, their reliance on and responsiveness to government green subsidies may differ significantly from those of non-polluting firms, thereby affecting the effectiveness of such subsidies in promoting green innovation. Therefore, this study conducts a heterogeneity analysis based on whether a firm belongs to a heavily polluting industry. The samples were classified according to whether the family firms were heavily polluting or not, and divided into non-heavily polluting and heavily polluting family firms.

According to the test results in

Table 7, it can be found that, regardless of whether they are heavily polluting family firms or not, government green subsidies significantly promote both substantive and strategic green innovation in family firms. According to the size of the correlation coefficients, it can be found that for both types of green innovation, government green subsidies have a stronger promoting effect on non-heavily polluting family firms. The possible reason is that they hope to respond quickly to the green demand of the market and the green policy orientation of the government through strategic green innovation, such as optimizing product packaging to make it more environmentally friendly and adopting some relatively simple energy-saving production technologies. However, the innovation motivation of heavily polluting family firms may be more inclined to maintain the status quo or minimize costs. For heavily polluting family firms, substantive green innovation requires a large amount of capital, manpower, and time, and the innovation results are uncertain. Non-heavily polluting family firms have a lower pollution level themselves and have the opportunity to further optimize their image through green innovation, open up the green market, and thus obtain more market share and long-term economic benefits.

5.3. Executive Green Cognition

As the core of corporate decision-making [

71], executives’ green cognition directly influences the strategic direction and resource allocation efficiency of green innovation [

72]. Executives with a higher level of green cognition are more likely to view green innovation as a critical means of enhancing corporate competitiveness and fulfilling social responsibility, thereby prioritizing resources for green R&D and utilizing government green subsidies and other external resources more effectively to promote substantive or strategic green innovation. Meanwhile, differences in executives’ green cognition may result in inconsistencies in the effectiveness of government green subsidy policies. Executives with lower levels of green cognition may fail to fully leverage subsidy resources, thereby impacting policy outcomes. This effect is particularly pronounced in family firms, where family values significantly shape executive decision-making, and green cognition plays a vital role in guiding green innovation strategies [

73]. To examine the heterogeneous impact of executives’ green cognition in this study, the sample of family firms was divided into two groups based on the average level of executives’ green cognition, using the average as the threshold to distinguish between high and low cognition levels.

According to the test results in

Table 8, it is found that government green subsidies play a promoting role under the two different levels of executives’ green cognition. By observing the correlation coefficients, it can be found that, whether it is substantial green innovation or strategic green innovation, the promoting effect of a higher level of executives’ green cognition is stronger. The possible reasons are as follows: compared with executives with a low level of green awareness, executives with a high level of green awareness in family enterprises have a deeper understanding of government green policies. They are able to accurately identify the direction of government subsidies and align their green innovation projects with policy objectives. This not only enables them to obtain subsidies more easily but also allows them to utilize the funds more effectively. For example, they are more likely to direct the subsidy funds towards key R&D areas of substantial green innovation, such as the development of new energy-saving technologies. In addition, their strong policy sensitivity enables them to respond promptly to policy guidance, adjust the strategic direction of the enterprise, and increase investment in green innovation.

Moreover, executives with a high level of green awareness possess stronger resource integration and allocation capabilities, as well as more scientific innovation strategies and a higher risk-bearing capacity. They can attract external resources, such as collaborating with research institutions, and optimize internal resource allocation, using government subsidies to drive both substantial and strategic green innovation. Their long-term strategic planning and the ability to flexibly adjust strategies enable them to make the most of the subsidies. In the face of the high risks and uncertainties of green innovation, they are more willing to take risks and can effectively manage these risks with the support of government subsidies, ensuring the smooth progress of green innovation projects.

5.4. Firm Life Cycle Heterogeneity

The life cycle of family firms can be categorized into the growth stage, maturity stage, and decline stage, with enterprises in different stages exhibiting significant heterogeneity in resource utilization, strategic goals, and innovation drivers [

74]. During the growth stage, firms typically focus on expanding market share, with green innovation efforts primarily aimed at improving product quality and technological competitiveness. Their high demand for resources often leads to a more proactive approach in seeking government subsidies and external support. In the maturity stage, firms enjoy relatively abundant resources and are more inclined to pursue long-term and forward-looking green innovation to fulfill social responsibilities and comply with environmental regulations, demonstrating higher efficiency in utilizing policies. In the decline stage, firms face dual pressures of market competition and resource constraints, which may weaken their motivation for green innovation [

75]. These firms tend to adopt cost-saving green technologies and exhibit greater reliance on external support, such as government subsidies. To examine the heterogeneity of government subsidies’ effects on strategic green innovation and substantive green innovation across differet life cycle stages of family firms, referring to the relevant research of Dickinson (2011), the sample of family firms was divided into three stages: growth stage, maturity stage, and decline stage, using the cash flow classification method [

76].

In our study, the results of the heterogeneity test based on the enterprise life cycle are shown in

Table 9, we hypothesize that the reasons for the manifestation of heterogeneity are as follows: for the difference in strategic green innovation, Family firms in the growth stage are in rapid business expansion and have a strong demand for enhancing the corporate image and expanding market share. Government green subsidies provide them with additional financial support, enabling them to carry out strategic green innovation without bearing excessive financial risks. Family firms in the maturity stage usually have relatively abundant funds, technology, and human resources. They have already established a firm foothold in the market and have stable cash flow and profit sources. Government green subsidies serve as an additional resource for family firms, enabling them to undertake strategic green innovation without disrupting their core business operations. Family firms in the decline stage focus on maintaining the survival of the enterprise and solving the current business difficulties.

For the difference in substantive green innovation, similar to the discussion above, government green subsidies offer essential financial support to family firms in the growth stage, easing the financial burden associated with substantive green innovation. Family firms in the maturity stage have already achieved a stable position in the market and have mature products and production processes. They often have a technological path dependence and may be more cautious about large-scale substantive green innovation. Substantive green innovation becomes an important opportunity for them to reverse the situation and achieve transformation, and government green subsidies provide part of the funds required for transformation. Family firms in the decline stage hope to use government green subsidies to promote substantive green innovation to reverse the decline trend.

6. Conclusions and Implications

We provide a comprehensive and in-depth analysis of the complex relationships between government green subsidies, economic policy uncertainty, and family firm green innovation, using panel data from A-share listed family firms spanning 2008 to 2022. The research reveals that government green subsidies play a pivotal role in facilitating the green innovation process of family firms. Both strategic and substantive green innovations have been significantly promoted by government green subsidies. This is mainly because family firms usually face relatively severe financing constraints, and the intervention of government green subsidies effectively alleviates the crowding-out of operating funds by R&D costs, enabling firms to obtain sufficient funds to invest in green innovation activities [

77]. Economic policy uncertainty has become an important negative factor affecting this positive process, having a significant negative moderating effect on the promoting role of government green subsidies. With the continuous rise in economic policy uncertainty, the external risks faced by family firms have risen sharply. In this case, family firms tend to allocate more limited funds to maintaining existing business activities in order to maintain their stable operation, thus having to reduce investment in green R&D, which largely weakens the original incentive effect of government green subsidies on green innovation [

78].

Further analysis reveals that government green subsidies enhance both substantive and strategic green innovation in family firms through a mediating mechanism by promoting increased R&D investment. The heterogeneity analysis further shows that non-heavily polluting family firms exhibit more significant improvements in both strategic and substantive green innovation after receiving government green subsidies compared with their heavily polluting counterparts. For firms with lower levels of managerial green cognition, the effect of subsidies is more pronounced in promoting substantive green innovation. In contrast, among firms with higher levels of managerial green cognition, subsidies are more effective in stimulating strategic green innovation. In terms of firm life cycle stages, government green subsidies significantly promote strategic green innovation in family firms during the growth and maturity stages, but this effect is not observed during the decline stage. Regarding substantive green innovation, subsidies have a significant positive impact on firms in the growth and decline stages, whereas their effect on mature-stage firms is not statistically significant.

Based on the above conclusions, we propose some implications as follows.

The government should continuously refine the green subsidy policy system to improve the precision and effectiveness of subsidy measures. When formulating subsidy standards, fully consider factors such as the industry characteristics, size, and innovation ability of family firms, and implement differentiated subsidy strategies for different types of firms to ensure that subsidy funds accurately flow to family firms that need support most and have great innovation potential, maximizing the incentive effect of subsidy funds. Meanwhile, strengthen policy publicity and interpretation work, through online and offline multi-channel and multi-form training and communication activities, help family firms deeply understand the application conditions, procedures, and expected effects of green subsidy policies, and improve the awareness and application enthusiasm of enterprises for policies. In addition, establish a policy effect tracking and evaluation mechanism, regularly conduct quantitative evaluations of the implementation effects of green subsidy policies, and adjust and optimize the policy content and implementation methods in a timely manner according to the evaluation results to ensure that the policies always meet the needs of family firm green innovation development and market dynamics.

Family firms should enhance their awareness of green innovation, embed the concept of green development into their core business strategies, and actively pursue green innovation opportunities. On the one hand, increase the introduction and cultivation of green innovation talents, build a diversified and professional innovation talent team, and enhance the green technology research and development and management capabilities of talents through internal training and external cooperation, providing solid intellectual support for green innovation. On the other hand, efforts should be made to strengthen the development of internal green innovation management mechanisms within enterprises, optimize the decision-making process for innovation projects, enhance the efficiency of innovation resource allocation, and ensure the orderly and effective implementation of green innovation activities. At the same time, focus on building strong collaborative relationships with external research institutions, universities, and upstream and downstream enterprises, integrate the advantageous resources of all parties, break through the limitations of their own innovation, jointly promote the research and application of green technology, and enhance the overall strength and market competitiveness of enterprise green innovation, achieving sustainable growth and family wealth inheritance in the wave of green development.

Future research may further extend the perspective and methodology of this study. On the one hand, combining micro-level survey data would allow for a deeper examination of how family governance structures, such as intergenerational succession and the degree of family control, shape firms’ responses to green innovation policies. On the other hand, it would be valuable to explore the differentiated impacts of various types of green policy instruments, such as green credit and green taxation, on corporate environmental behavior. In addition, cross-country comparative studies could provide richer empirical evidence for understanding the institutional boundaries that influence the effectiveness of green subsidy policies.