Accessing Geological Heritage in Slovakia: Between Politics and Law

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Theoretical Framework

3.1. Geotourism and the Law in Slovakia

3.2. Geotourism and Slovak Policy

4. Discussion

4.1. Geotourism Outside the Law: Possible Causes

4.2. State of the Progress

4.2.1. Perceived Problems

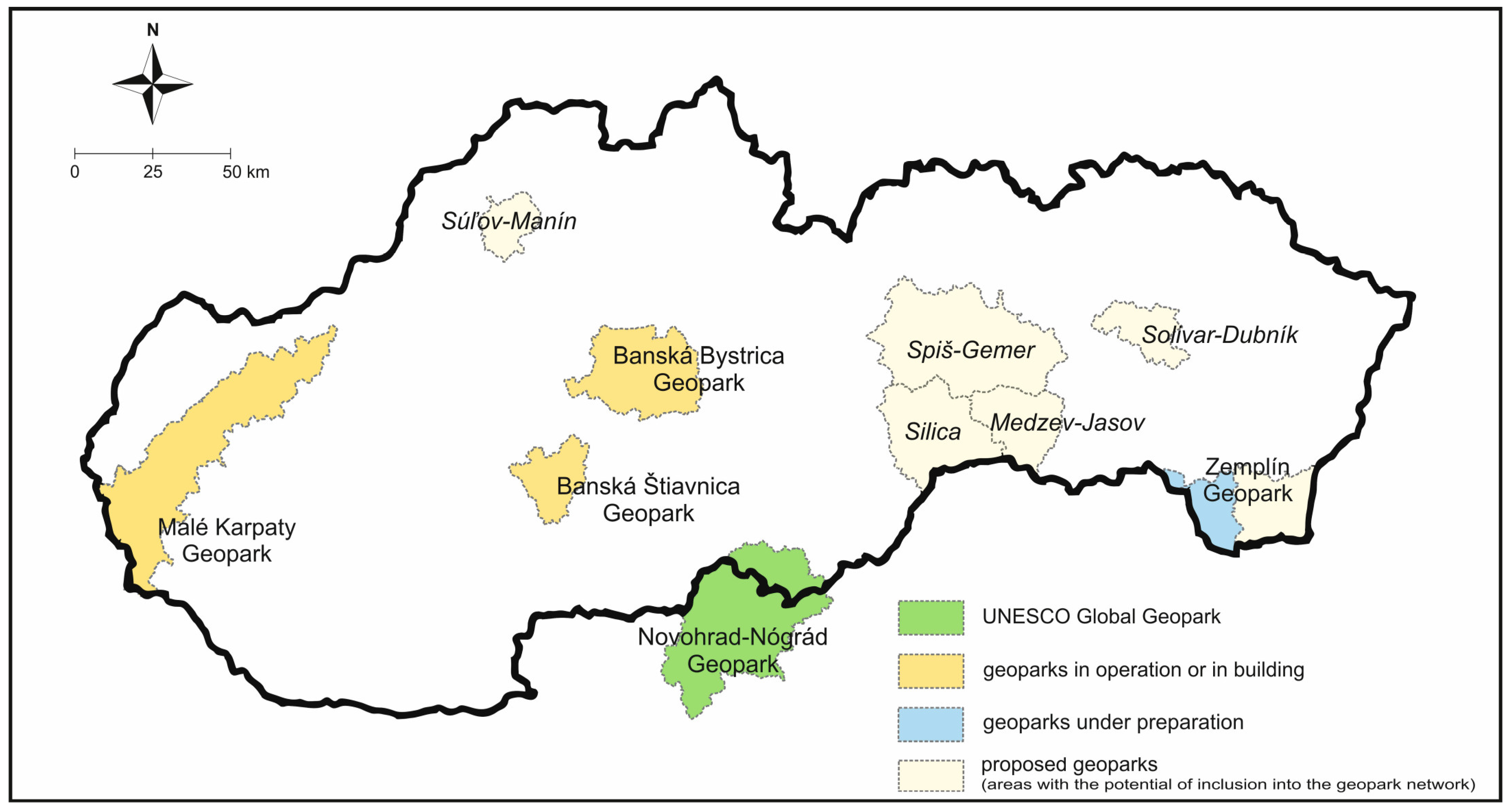

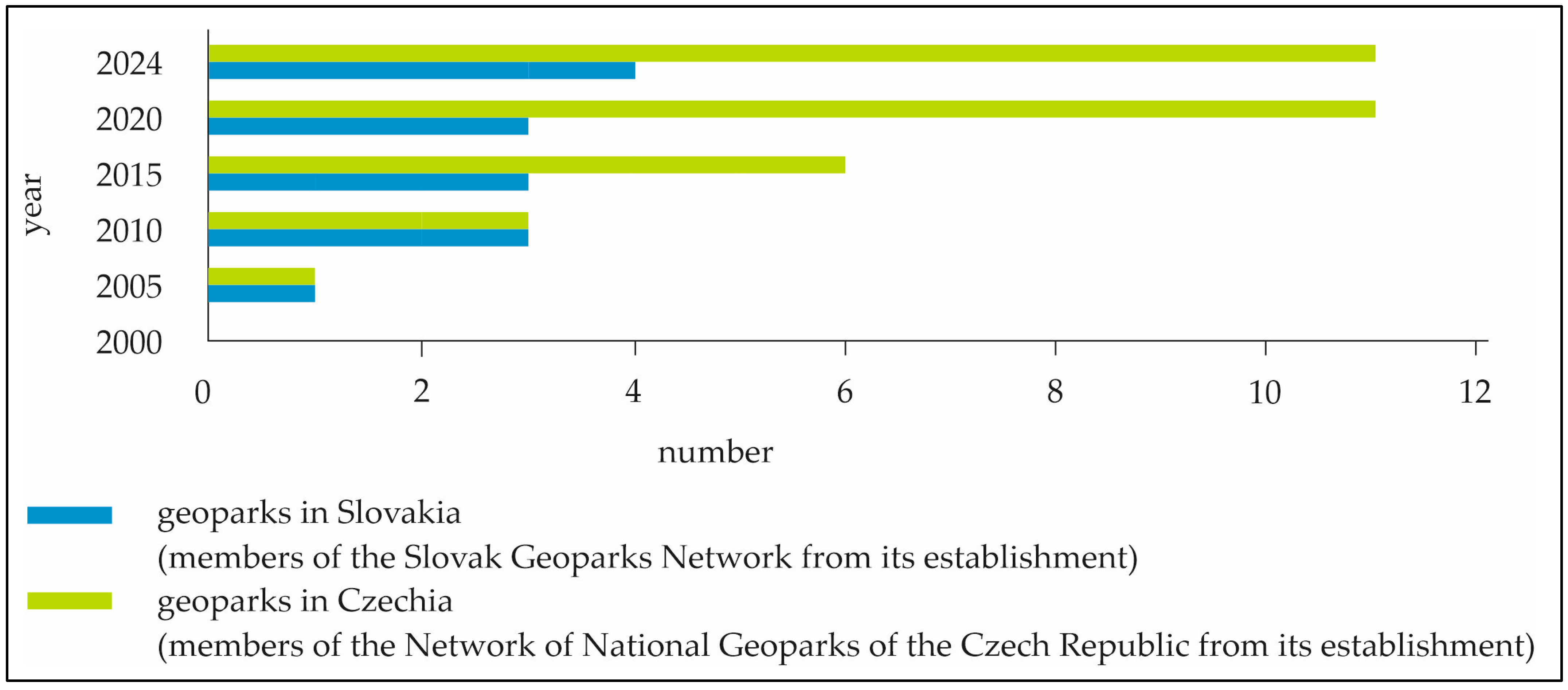

4.2.2. Quantifiable Status Achieved

4.2.3. International Comparison

4.3. Potential Benefits of Legal Regulation of Geotourism

4.3.1. Solution of “Authority Problem”

4.3.2. Solution of “Acceptance Problem”

4.3.3. Coping an International Element

4.3.4. Extension of Supplementary Protection of Geological Phenomena

4.3.5. Strengthening Transparency and Legal Certainty

4.3.6. Development of Geotourism as a Public Interest

4.3.7. Solution for the “Ambivalence Problem”

4.3.8. Other Caused Benefits

4.3.9. Solution for the “Discontinuity Problem”

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hose, T. Selling the Story of Britain’s Stone. Environ. Interpret. 1995, 10, 16–17. [Google Scholar]

- Dowling, R.K.; Newsome, D. The scope and nature of geotourism. In Geotourism; Dowling, R., Newsome, D., Eds.; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2006; pp. 31–53. [Google Scholar]

- Dowling, R.K.; Newsome, D. (Eds.) Global Geotourism Perspective; Goodfellow Publishers Limited: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hose, T.A. 3G’s for modern geotourism. Geoheritage 2012, 4, 7–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowling, R.K. Global geotourism—An emerging form of sustainable tourism. Czech J. Tour. 2013, 2, 59–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hose, T.A. (Ed.) Geoheritage and Geotourism: A European Perspective; The Boydell Press: Woodbridge, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hose, T.A. (Ed.) Appreciating Physical Landscapes: Three Hundred Years of Geotourism; The Geological Society: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Arouca Declaration. Available online: https://www.dropbox.com/scl/fi/wdyczmxwvc0dsizzwe291/Declaration_Arouca_-EN.pdf?rlkey=3l42q9bpsea3nr97gmlkn5otb&e=1&dl=0 (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Dowling, R.K. Geotourism. In The Encyclopedia of Sustainable Tourism; Cater, C., Garrod, B., Low, T., Eds.; CABI: Oxford, UK, 2015; pp. 231–232. [Google Scholar]

- Newsome, D.; Dowling, R.K. Geoheritage and Geotourism. In Geoheritage: Assessment, Protection, and Management; Reynard, E., Brilha, J., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 305–322. [Google Scholar]

- Návrh Koncepcie Geoparkov v SR. Available online: https://www.geopark.sk/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/03-vlastnymat.pdf (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- Aktualizácia Koncepcie Geoparkov SR. Available online: https://www.geopark.sk/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/03vlastnymat2015.pdf (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- Dickson, J. Methodology in Jurisprudence: A Critical Survey. Leg. Theory 2004, 10, 117–156. [Google Scholar]

- Tobia, K. Methodology and Innovation in Jurisprudence. Columbia Law. Rev. 2023, 123, 2483–2515. [Google Scholar]

- Pathak, R.; Rabindra, K. Historical Approach to Legal Research. In Legal Research and Methodology Perspectives, Process and Practice; Nirmal, B.C., Singh, R.K., Nirmal, A., Eds.; Satyam Law International: New Delhi, India, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Jurčová, M.; Dobrovodský, R.; Nevolná, Z.; Olšovská, A. Právo Cestovného Ruchu; C.H. Beck: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Petráš, R. Právo a Cestovní Ruch; Univerzita Jana Amose Komenského Praha: Prague, Czech Republic, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Magurová, H. Základy Práva Cestovného Ruchu Pre Ekonómov; Wolters Kluwer: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Jurčová, M.; Borkovičová, V.; Maslák, M. Spotrebiteľské Právo; Wolters Kluwer: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lukáč, M. K Systému Slovenské Právní úpravy Cestovního Ruchu. Stud. Tur. 2018, 9, 51–58. [Google Scholar]

- 91/2010 Z.z.-zákon o Podpore Cestovného Ruchu. Available online: https://www.slov-lex.sk/ezbierky/pravne-predpisy/SK/ZZ/2010/91/?ucinnost=06.03.2025 (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- 303/2024 Z.z.-zákon o Fonde na Podporu Cestovného Ruchu. Available online: https://static.slov-lex.sk/static/SK/ZZ/2024/303/20250101.html (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Dôvodová Správa k Zákonu č. 303/2024 o Fonde na Podporu Cestovného Ruchu. Available online: https://www.aspi.sk/products/lawText/7/350761/1/2/dovodova-sprava-c-lit350761sk-dovodova-sprava-k-zakonu-c-303-2024-zz-o-fonde-na-podporu-cestovneho-ruchu (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Programové Vyhlásenie Vlády Slovenskej Republiky 2006. Available online: http://mepoforum.sk/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/Vyhlasenie_SK.pdf (accessed on 4 December 2024).

- Hašanová, J. Správne Právo: Všeobecná a Osobitná Časť; Veda: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Košičiarová, S.; Damohorský, M.; Dudová, J.; Jančárová, I.; Kozová, M.; Kružíková, E.; Kučerová, E.; Mezřický, V.; Patakyová, M.; Pekárek, M.; et al. Právo Životného Prostredia—Všeobecná Časť; Heuréka: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Drgonec, J. Štát a Právo v Službách Životného Prostredia; Abies: Prešov, Slovakia, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Švihlová, D.; Lieskovská, Z.; Kontić, B.; Palúchová, K.; Slotová, S.; Čerkala, E. Legislatívne Aspekty Životného Prostredia; Pedagogická spoločnosť Jána Amosa Komenského: Banská Bystrica, Slovakia, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 543/2002-Zákon o Ochrane Prírody a Krajiny. Available online: https://www.slov-lex.sk/pravne-predpisy/SK/ZZ/2002/543 (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- 44/1988 Zákon o Ochrane a Využití Nerastného Bohatstva (Banský Zákon). Available online: https://www.slov-lex.sk/ezbierky/pravne-predpisy/SK/ZZ/1988/44/ (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- 51/1998 Zákon o Banskej Činnosti, Výbušninách a o Štátnej Banskej Správe. Available online: https://www.slov-lex.sk/ezbierky/pravne-predpisy/SK/ZZ/1988/51/ (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- Nová Stratégia Cestovného Ruchu na Slovensku do Roku 2013. Available online: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&source=web&rct=j&opi=89978449&url=https://08224909112467312927.googlegroups.com/attach/9888f6a5784f8cc9/Nov%25C3%25A1%2520strat%25C3%25A9gia%2520cestovn%25C3%25A9ho%2520ruchu%2520na%2520Slovensku.pdf%3Fpart%3D0.8%26vt%3DANaJVrHEdvS5dEC4by0Yhr7FMg0A6cTfgaf_rFY0ZDzXHDNqZDHSFWKcIfr_rQPmW6mqIu5Fz-hFRTOI0qnpm520JzeH1Kq-QdWJpNcKoCv8Yj72q3lg2bo&ved=2ahUKEwi5ye3rvPWLAxUHxQIHHfUnBmoQFnoECBUQAQ&usg=AOvVaw2kcc2ImH3gU68jSfc2p6t8 (accessed on 14 December 2024).

- Rybár, P.; Baláž, B.; Štrba, Ľ. Geoturizmus—Identifikácia Objektov Geoturizmu; Edičné stredisko FBERG TUKE: Košice, Slovakia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández, G.; Ramos, A.; Valenzuela, S.; Ricci, S. Geodiversity, mining heritage and geotourism: Proposed geo-mining Park in Argentina. Anu. Tur. Y Soc. 2015, 17, 17–37. [Google Scholar]

- Rybár, P. Banský Turizmus; Edičné stredisko FBERG TUKE: Košice, Slovakia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Rybár, P.; Štrba, L. Mining tourism and its position in relation to other forms of tourism. In Proceedings of the Geotour 2016, Florence, Italy, 18–20 October 2016; Ugolini, F., Marchi, V., Trampetti, S., Pearlmutter, D., Raschi, A., Eds.; IBIMET-CNR: Florence, Italy, 2016; pp. 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Ruchkys, U.; Panisset Travassos, L.E.; Rezun, B. Mines that value geomining heritage for tourism and education: The examples of Idrija (Slovenia) and Passagem (Minas Gerais-Brazil). Atelie Geogr. 2017, 11, 223–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mata-Perelló, J.; Carrión, P.; Molina, J.; Villas-Boas, R. Geomining heritage as a tool to promote the social development of rural communities. In Geoheritage: Assessment, Protection, and Management; Reynard, E., Brilha, J., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 167–177. [Google Scholar]

- Scheibal, C. Geoturizmus; Technická univerzita v Košiciach: Košice, Slovakia, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Krnáč, J.; Kožiak, R.; Liptáková, K. Verejná Správa a Regionálny Rozvoj; Univerzita Mateja Bela: Banská Bystrica, Slovakia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Cibáková, V.; Malý, I. Verejná Politika a Regionálny Rozvoj; Iura edition: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Čajka, P. Regionálny Rozvoj v 21. Storočí; Belianum: Banská Bystrica, Slovakia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Miśkiewicz, K. Geotourism Product as an Indicator for Sustainable Development in Poland. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geoparks of the Slovak Republic. Available online: http://geopark.sk/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/priloha_2.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2020).

- Novohrad-Nograd Geopark. Available online: https://www.europeangeoparks.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/nngeopark_location.jpg (accessed on 2 March 2025).

- Aktualizácia Národnej Stratégie Regionálneho Rozvoja SR. Available online: https://www.enviroportal.sk/eia/detail/aktualizacia-narodnej-strategie-regionalneho-rozvoja-sr (accessed on 12 October 2024).

- Uznesenie Vlády SR 593/2008. Available online: https://hsr.rokovania.sk/data/att/51442_subor.doc (accessed on 13 October 2024).

- Analýza Sociálno-Ekonomickej Situácie Okresu Trebišov a Návrhy na Zlepšenie v Sociálnej a Hospodárskej Oblasti. Available online: https://rokovania.gov.sk/RVL/Material/12432/1 (accessed on 13 October 2024).

- Action Plan for Implementation of Measures to Ensure the Implementation of the Updated Geopark of the Slovak Republic. Available online: http://geopark.sk/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/akcny_plan_aktualizovana_koncepcia_GP_SR_2016.pdf (accessed on 13 October 2024).

- Program Rozvoja Vidieka SR na Programové Obdobie 2014–2020. Available online: https://www.partnerskadohoda.gov.sk/program-rozvoja-vidieka-sr-na-programove-obdobie-2014-2020/ (accessed on 13 October 2024).

- Panizza, M.; Piacente, S. Geomorfologia Culturale; Bologna: Editrice Pitagora, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Pásková, M.; Zelenka, J.; Ogasawara, T.; Zavala, B.; Astete, I. The ABC Concept—Value Added to the Earth Heritage Interpretation. Geoheritage 2021, 13, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pijet-Migoń, E.; Migoń, P. Geoheritage and Cultural Heritage—A Review of Recurrent and Interlinked Themes. Geosciences 2022, 12, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 109/1961 Zb. Zákon o Múzeách a Galériách. Available online: https://www.slov-lex.sk/ezbierky/pravne-predpisy/SK/ZZ/1961/109/vyhlasene_znenie.html (accessed on 4 December 2024).

- Čerkala, E. Právo Životného Prostredia a Politika (Vybrané Problémy); TU vo Zvolene: Zvolen, Slovakia, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 49/2002 Zb. Zákon o Ochrane Pamiatkového Fondu. Available online: https://www.slov-lex.sk/ezbierky/pravne-predpisy/SK/ZZ/2002/49/ (accessed on 4 December 2024).

- 83/1990 Zb. Zákon o Združovaní Občanov. Available online: https://www.slov-lex.sk/ezbierky/pravne-predpisy/SK/ZZ/1990/83/ (accessed on 4 December 2024).

- 40/1964 Zb. Občiansky Zákonník. Available online: https://www.slov-lex.sk/ezbierky/pravne-predpisy/SK/ZZ/1964/40/ (accessed on 4 December 2024).

- 213/1997 Zb. Zákon o Neziskových Organizáciách Poskytujúcich Všeobecne Prospešné Služby. Available online: https://www.slov-lex.sk/ezbierky/pravne-predpisy/SK/ZZ/1997/2013/ (accessed on 4 December 2024).

- Farsani, N.T.; Coelho, C.; Costa, C.; de Carvahlo, C.N. (Eds.) Geoparks & Geotourism: New Approaches to Sustainability For the 21st Century; Brown Walker Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Nikolova, V.; Sinnyovsky, D. Geoparks in the legal framework of the EU countries. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2019, 29, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girault, Y. (Ed.) UNESCO Global Geoparks. In Tension Between Territorial Development and Heritage Enhancement; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Henriques, M.H.; Brilha, J. UNESCO Global Geoparks: A strategy towards global understanding and sustainability. Episodes 2017, 40, 349–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, M.; Schäefer, K.; Büchel, G.; Patzak, M. Geoparks—A regional, European and global policy. In Geotourism, Sustainability, Impacts and Management; Newsome, D., Dowling, R.K., Eds.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2006; pp. 96–117. [Google Scholar]

- Zhechkov, R.; Hinojosa, C.; Knee, P.; Pinzón, L.; Buchs, D.; Chernet, T. Evaluation of the International Geoscience and Geoparks Programme. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000373234/PDF/373234eng.pdf.multi (accessed on 14 October 2024).

- Guidance of the Interdepartmental Commission of the SR Geoparks Network. Available online: http://geopark.sk/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Usmernenie-MKSG-SR.pdf (accessed on 4 December 2024).

- Smolka, J. Prvý slovenský geopark. Enviromagazín 2006, 5, 28–29. [Google Scholar]

- Novohrad-Nograd Geopark. Available online: https://www.nogradgeopark.eu/en/novohrad-nograd-geopark (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- História Vzniku—Banskobystrický Geomontánny Park. Available online: https://www.geoparkbb.sk/mas-geopark/organizacia/historia-vzniku/ (accessed on 18 October 2024).

- Štátna Politika Cestovného Ruchu Slovenskej Republiky. Available online: https://lrv.rokovania.sk/data/att/96196_subor.doc (accessed on 11 December 2024).

- Koncepcia Geologického Výskumu a Geologického Prieskumu Územia Slovenskej Republiky na Roky 2012–2016 (s Výhľadom do Roku 2020). Available online: https://rokovania.gov.sk/RVL/Material/8304/1 (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Programové Vyhlásenie Vlády SR 2012. Available online: https://old.ezdravotnictvo.sk/Documents/programove_vyhlasenie_2010.pdf (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Stratégia Rozvoja Cestovného Ruchu do Roku 2020. Available online: https://vraji.sk/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Strategia-rozvoja-CR-v-SR-do-r.-2020.pdf (accessed on 12 September 2024).

- Geoparks Network of the Slovak Republic. Available online: https://www.geopark.sk/en/geoparks-network-of-the-slovak-republic/ (accessed on 12 October 2024).

- Programové Vyhlásenie Vlády 2016–2020. Available online: https://www.mosr.sk/data/att/163322.pdf (accessed on 13 October 2024).

- Programové Vyhlásenie Vlády 2020–2024. Available online: https://www.nrsr.sk/web/Dynamic/DocumentPreview.aspx?DocID=477513 (accessed on 13 October 2024).

- Programové Vyhlásenie Vlády 2023–2027. Available online: https://www.nrsr.sk/web/Dynamic/DocumentPreview.aspx?DocID=535376 (accessed on 13 October 2024).

- Carvalho, C.N.; Rodrigues, J. Building a geopark for fostering socio-economic development and to burst culture pride: The Naturtejo European Geopark (Portugal). In Una Vision Multidisciplinar Del Patrimonio Geológico Y Minero, Cuadernos Del Museo Geominero, 12; Florido, P., Rábano, I., Eds.; IGME: Madrid, Spain, 2010; pp. 467–479. [Google Scholar]

- Hoblea, F.; Cayla, N.; Reynard, E. Managing Geosites in Protected Areas: An introduction. Collect. Edytem Cah. Géographie 2013, 15, 11–12. [Google Scholar]

- Kučerová, J. Trvalo Udržateľný Rozvoj Cestovného Ruchu; Ekonomická fakulta UMB v Banskej Bystrici: Banská Bystrica, Slovakia, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Huba, M.; Hudek, V.; Chrenko, M.; Ira, V.; Kováč, M.; Kozová, M.; Mederly, P.; Šivhlová, D.; Toma, P.; Vilinovič, K. Trvalo Udržateľný Rozvoj—Výzva Pre Slovensko. Regionálne environmentálne centrum pre krajiny strednej a východnej Európy: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Huba, M.; Kozová, M.; Mederly, P. Miestna Agenda 21. In Udržateľný Rozvoj Obcí a Mikroregiónov Na Slovensku; Regionálne environmentálne centrum pre krajiny strednej a východnej Európy: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kučerová, J. Plánovanie a Politika v Cieľových Miestach Cestovného Ruchu; Belianum: Banská Bystrica, Slovakia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Správa o Realizácii Koncepcie Geoparkov SR. Available online: https://www.geopark.sk/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/sprava.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2024).

- Methodology for Geopark Destination Management. Available online: http://geopark.sk/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Metodika-pre-destinacny-manazment-geoparku.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2024).

- Information on Implementation of the Updated Concept of Geoparks in Slovakia 2015–2018. Available online: http://www.geopark.sk/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/1.pdf (accessed on 4 November 2024).

- Lukáč, M.; Petráš, R. Divergence českého a slovenského práva a cestovní ruch. Stud. Tur. 2024, 15, 40–52. [Google Scholar]

- Koncepce Národních Geoparků. Available online: http://www.geology.cz/narodnigeoparky/koncepce-ng (accessed on 3 January 2025).

- Gorica, K.; Kripa, D. Engjellushe Zenela: The Role of Local Government in Sustainable Development. Œconomica 2012, 8, 139–155. [Google Scholar]

- Borges, M.; Eusébio, C.; Carvalho, N. Governance for sustainable tourism: A review and directions for future research. Eur. J. Tour. Res. 2014, 7, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocio, H.-G.; Jaime, O.-C.; Cinta, P.-C. The Role of Management in Sustainable Tourism: A Bibliometric Analysis Approach. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- d’Angella, F.; Maccioni, S.; De Carlo, M. Exploring destination sustainable development strategies: Triggers and levels of maturity. Sustain. Futures 2025, 9, 100515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Geoscience and Geoparks Programme. Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/iggp (accessed on 3 January 2025).

- Slovak-Hungarian GeoTouristic Partnership. Available online: https://www.skhu.eu/funded-projects/slovak-hungarian-geotouristic-partnership (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- Brilha, J. Geoheritage and Geoparks. In Geoheritage: Assessment, Protection and Management; Reynard, E., Brilha, J., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 323–338. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, M. Geodiversity: Valuing and Conserving Abiotic Nature; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Scottish Fossil Code. Available online: https://www.nature.scot/scottish-fossil-code (accessed on 4 January 2025).

- Judikatúra Súdov Slovenskej Republiky. Available online: https://www.judikaty.info/ustavny-sud-slovenskej-republiky/princip-legality (accessed on 4 January 2025).

- 552/2003 Z. z. Zákon o Výkone Práce vo Verejnom Záujme. Available online: https://www.slov-lex.sk/ezbierky/pravne-predpisy/SK/ZZ/2003/552/ (accessed on 4 January 2025).

- Stratégia Rozvoja Cestovného Ruchu v Okrese Gelnica na Obdobie Rokov 2019–2027 (Výhľadovo 2030). Available online: https://www.enviroportal.sk/eia/detail/strategia-rozvoja-cestovneho-ruchu-v-okrese-gelnica-na-obdobie-rokov-2 (accessed on 4 January 2025).

- UNESCO Global Geoparks. Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/iggp/geoparks/about (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- 524/2011 Z. z. Vyhláška Ministerstva Hospodárstva Slovenskej Republiky, Ktorou sa Ustanovujú Podrobnosti o Postupe pri Povoľovaní Sprístupňovania Banských Diel a Starých Banských Diel na Múzejné a Iné Účely a Prác na Ich Udržiavaní v Bezpečnom Stave. Available online: https://www.epi.sk/zz/2011-524 (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Ferreira, D.R.; Valdati, J. Geoparks and Sustainable Development: Systematic Review. Geoheritage 2023, 15, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maršálek, P. Příběh Moderního Práva; Auditorium: Prague, Czech Republic, 2018. [Google Scholar]

| Geopark | Operator | Legal Form | Regulation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Banská Štiavnica Geopark | ZZPO Región Sitno | Interest association of legal entities | Civil Code No. 40/1964 Coll. [58] |

| Novohrad–Nógrád UNESCO Global Geopark | Združenie právnických osôb Geopark Novohrad–Nógrád | Interest association of legal entities | Civil Code No. 40/1964 Coll. [58] |

| Banská Bystrica Geopark | Banskobystrický geomontánny park | Civic association | Act on Citizens’ Associations No. 83/1990 Coll. [57] |

| Malé Karpaty Geopark | Barbora n. o. | Non-profit organisation | Act on Non-Profit Organisations Providing Public Benefit Services No. 213/1997 Coll. [59] |

| Year | Document | Official Name in Slovak | Legal Form | Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2006 | Programme Statement of the Government | Programové vyhlásenie vlády | Political Declaration | Introduction of the Concept |

| 2008 | Draft Concept of Geoparks | Návrh koncepcie geoparkov | Government Decree No. 740/2008 | The Concept of the Geoparks (1) [11] |

| 2012 | Report on the Implementation of the Concept of Geoparks | Správa o realizácii Koncepcie geoparkov | Government Decree No. 608/2012 | Recapitulation of the past development |

| 2015 | Actualisation of the Concept of Geoparks | Aktualizácia koncepcie geoparkov SR | Government Decree No. 15/2015 | The Concept of the Geoparks (2) [12] |

| 2016 | Action plan for the Implementation of the Updated Concept | Akčný plán na implementáciu aktualizovanej koncepcie | Ministerial Decision | Strategy for further progress |

| 2019–2024 | Information on the Implementation of the Updated Concept (Onward periodically every 5 years) | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lukáč, M.; Štrba, Ľ. Accessing Geological Heritage in Slovakia: Between Politics and Law. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4525. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104525

Lukáč M, Štrba Ľ. Accessing Geological Heritage in Slovakia: Between Politics and Law. Sustainability. 2025; 17(10):4525. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104525

Chicago/Turabian StyleLukáč, Marián, and Ľubomír Štrba. 2025. "Accessing Geological Heritage in Slovakia: Between Politics and Law" Sustainability 17, no. 10: 4525. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104525

APA StyleLukáč, M., & Štrba, Ľ. (2025). Accessing Geological Heritage in Slovakia: Between Politics and Law. Sustainability, 17(10), 4525. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104525