1. Introduction

In a time of health crises and rising pressure on emergency services, the job stress that ambulance workers deal with has caught the eye of both researchers and practitioners. These first responders encounter challenges that come with their jobs, such as going through traumatic situations, long shifts, and making tough decisions under stress. Therefore, grasping the psychosocial elements that add to their job stress is essential for creating specific interventions to enhance their mental health and overall welfare. Recent research shows that the interaction of individual traits, workplace atmosphere, and broader issues greatly affects the experiences of ambulance staff [

1]. Research has pointed out how organizational factors, like managerial support and colleague relationships, can either lessen or worsen stress levels among this workforce [

2,

3]. Moreover, the complex nature of job stress among ambulance staff has been examined across different contexts, showing notable trends. A greater risk of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety, and depression in ambulance personnel during health crises has been noted, but evidence suggests that perceived support from the organization and proper training can reduce these risks [

4]. Despite important advancements in this field, significant gaps persist, especially in terms of longitudinal studies that can track the changing nature of stressors in response to shifts within emergency services. These aspects have their significance in understanding how stressors change over time on one side and the lasting impacts of stressors on mental health on the other [

5,

6]. Additionally, while many studies zero in on organizational aspects, there is a clear need for broader research that looks into individual coping methods and resilience-building strategies among paramedics [

7,

8]. The current literature also points to a shortage of specific interventions designed to strengthen the mental health of ambulance staff, particularly focusing on flexible training programs that mitigate their distinctive job risks [

9,

10]. Thus, while the field of occupational stress in emergency medical services is gaining recognition, a deeper understanding of personal, organizational, and systemic factors is essential for crafting effective strategies.

An extensive overview of occupational stress factors influencing ambulance personnel establishes a basis for improved intervention methods and increased workforce resilience in the future [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. The study of occupational stress factors and the general psychosocial environment (aspects of the job and work environment such as organizational climate or culture, work roles, interpersonal relationships at work, the design and content of tasks) [

17] for ambulance staff has made significant progress over the past decades. Early research highlighted the intense nature of emergency medical service (EMS) work, showing high levels of stress associated with traumatic events and unpredictable workloads. Groundbreaking studies laid the groundwork for understanding the psychological impact on these professionals, particularly concentrating on factors such as organizational culture and support mechanisms [

1,

2,

3,

7]. The focus on specific stressors gained traction through the 2010s, demonstrating how environmental hazards and colleague relationships lead to job dissatisfaction and emotional burnout among ambulance workers [

4,

18]. More recent research has put into perspective the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, indicating increased strain due to larger patient loads and greater exposure to risky situations [

15]. Newer studies have started to consider more personalized approaches, looking into how resilience and attachment styles impact ambulance personnel’s ability to manage stress [

5,

6]. These advancements highlight the significance of both structural and personal elements in shaping the work experiences of EMS staff. The growth of this body of work reflects an increasingly refined comprehension of the interactions between job stress factors and the psychosocial environment for ambulance staff.

Occupational stress factors for ambulance workers have drawn more attention, especially given their distinct working conditions that involve high demands and emotional strain. Studies show that emergency medical service (EMS) professionals often face serious stressors, like traumatic experiences and lack of staff, which negatively impact their mental health and job satisfaction [

1]. Research highlights that workplace violence—an all-too-common occurrence in emergency situations—also elevates stress levels among ambulance workers [

4]. This is worsened by the physical demands of their jobs, with findings showing a clear link between physically demanding tasks and increased stress [

18].

Recent studies have indicated that strong social ties can lower stress levels, with those having strong networks reporting better mental health outcomes. The issue of work–life balance also comes into play: evidence suggests that rotating shifts can increase fatigue and anxiety, affecting overall job performance and well-being [

5]. In this context, a good work–life balance and strong social ties are additionally important. Recent inquiries indicate that organizational backing, including training and resources, greatly reduces stress, pointing out that strategies aimed at improving these areas could boost the resilience of ambulance staff [

19]. For instance, a systematic review flagged crucial aspects influencing job stress, highlighting the need for targeted interventions and educational schemes to promote better coping strategies [

20,

21]. Thus, creating a supportive psychosocial environment is key in reducing job stress and ensuring the effective functioning of ambulance services.

The methods used to investigate job stress factors of ambulance personnel reveal varied insights and findings. Qualitative studies, such as those using phenomenological interviews, provide rich details reflecting the experiences of paramedics, shedding light on the complex effects of stress on their work and personal lives [

1]. For example, research using qualitative methods reveals that relationships among colleagues are crucial in alleviating stress, underscoring the importance of peer support systems [

19]. Quantitative methods, including extensive surveys and statistical analyses, allow for the assessment of stress levels across different demographics and conditions. For instance, studies using standard questionnaires have noted elevated psychological distress among ambulance workers, connecting these results to particular stressors such as overcommitment and poor support systems. Mixed-method approaches have also proven valuable, combining qualitative insights with quantitative data to present a more complete understanding of the elements impacting ambulance staff [

3]. This blend of methodologies has led to conclusions enhancing the necessity for tailored interventions that address both organizational and occupational stress factors [

4]. Additionally, research focusing on contextual factors, like the effects of rotating shifts and trauma exposure, shows how methodological choices can shape our understanding of occupational stress [

18,

22]. By using diverse methods, researchers can systematically explore the intricate relationships among individual, organizational, and environmental factors that affect the well-being of ambulance personnel, ultimately enriching the discussion on this critical public health area [

15].

The study of job stress factors and the psychosocial environment related to ambulance personnel offers a comprehensive theoretical framework, drawing from psychology, sociology, and organizational behavior. A key theoretical basis is the demand–control model [

23], which states that high demands in a job paired with low control elevate stress and health issues. This model is backed by findings showing that ambulance workers deal with high decision-making demands coupled with limited control in urgent situations [

1,

2]. Moreover, the job demands–resources (JD-R) theory [

24] supports this view by proposing that the balance between job demands and available resources can alleviate stress. Recent studies highlight how crucial social support within the workplace acts as a resource that can counterbalance these demands [

3,

4]. In this context, resilience becomes essential, as personal coping strategies and organizational support systems greatly influence how ambulance staff manage job stressors [

19,

22]. Attachment theory [

25] also provides insight into how team relationships affect stress levels and coping methods. Research shows that individuals with secure attachment styles may handle stress better than those with insecure styles, further stressing the importance of social dynamics in emergency medical settings [

15,

18]. Conversely, findings showing high rates of burnout and compassion fatigue among ambulance crews reflect the intense effects of continuous exposure to stressful situations, aligning with theories about emotional labor and its depletion [

1,

6]. Combined approaches that merge these theories give a comprehensive view of job stress in ambulance personnel, indicating a need for focused interventions that enhance both individual resilience and an adaptive organizational culture to tackle these challenges [

23].

Essential findings reveal that ambulance personnel face various stressors, especially increased exposure to traumatic events, long working hours, and workplace culture, which collectively elevate levels of psychological distress, such as PTSD, anxiety, and burnout [

1,

2]. Studies reaffirm that effective organizational support and personal resilience are vital elements for alleviating these stressors, emphasizing the need for thorough strategies that foster mental well-being among first responders [

3,

4]. Moreover, the implications of these findings expand to the wider field of emergency medical services, suggesting that advancements in training programs and support systems could substantially enhance not only individual ambulance personnel but also the overall effectiveness and resilience of emergency response teams. For instance, efforts to nurture peer support networks and organizational acknowledgment could reduce the isolation often experienced by ambulance staff, thus lessening stress reactions [

26]. Additionally, a proper knowledge of the psychosocial environment makes it possible to create specific strategies that diverge from generic solutions, better addressing the distinctive challenges faced by this group [

15,

18]. Also, there is a considerable gap regarding the individual coping strategies that ambulance personnel use, highlighting the need for further exploration into psychological characteristics that shape stress recovery and resilience, like attachment styles [

19,

22]. Ultimately, the urgent need for solid support systems that are adaptable to the unique psychosocial dynamics of this profession should be highlighted [

20,

21]. Looking ahead, combining empirical findings with practical frameworks will enhance ambulance personnel’s capacity to effectively manage job stress, ultimately fostering a more resilient and supportive emergency medical service workforce [

22].

This study aimed to find and examine the main stress factors that affect ambulance staff, looking at the larger problem of how these stressors impact their mental well-being and work satisfaction.

2. Materials and Methods

The existing literature shows a strong connection between job demands, stress reactions, and health impacts, with a clear need for research specifically geared towards ambulance crews [

1]. The central issue involves comprehending how different work-related stresses, along with organizational and environmental elements, contribute to a harmful work environment in ambulance services [

2]. This study used a mixed-method approach to thoroughly analyze both quantitative and qualitative data. The main goals involved identifying occupational stress factors and indirectly assessing their effects on mental health, as perceived by the ambulance personnel.

Quantitative data were collected via standard tools like the Effort–Reward Imbalance questionnaire [

27], which is well validated for assessing work-related stress among healthcare workers [

4]. We considered the 2012 long version of the ERI questionnaire [

28] with 22 Likert-scaled items: ten measuring reward, six measuring effort, and six measuring overcommitment.

The study used the Romanian version of the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire (COPSOQ) [

29]—COPSOQ II—medium-length questionnaire, including “demand” scales (scales related to the type of production and work tasks at the workplace), scales related to the organization of work and to job content, scales of relevance for interpersonal relations and for leadership, scales referring at the person–work interface level, and scales addressing the health and well-being of the employees.

Another instrument we considered was the NASA Task Load Index (NASA-TLX), a subjective workload assessment tool incorporating a multidimensional rating procedure for an overall workload score based on six subscales: mental demand, physical demand, temporal demand, performance, effort, and frustration. Ratings for each of the six subscales are obtained from the subjects following the completion of a task. A numeric rating ranging from 0 to 100 (least to most taxing) is assigned to each scale. Weights are determined by the subjects’ choices of the subscale most relevant to workload for them from a pair of choices. The weights are calculated from the tally of these choices from 15 combinatorial pairs created from the six subscales. The weights range from 0 to 5 (least to most relevant). The ratings and weights are then combined to calculate a weighted average for an overall workload score. Many studies eliminate these pairwise comparisons and refer to the test as “Raw TLX” [

30]. This study also used this approach, considering only the numeric rating.

Qualitative data were recorded from non-structured interviews, allowing participants to share their experiences, in line with past research that highlights the necessity of understanding the subjective aspects of work-related stress [

18,

19]. Also, we examined the personal experiences of ambulance staff through work task analysis (job descriptions, including the description of both physical and mental activities, task complexity, environmental conditions) and document analysis (e.g., data records on the number of cases per shift by periods of the day/year).

This combined method is important for its methodological strength and the ability to connect factual data with personal stories, providing a complex, ergonomic view of the topic [

4,

19]. By systematically addressing these areas, this research aimed to support evidence-based efforts to improve the well-being of ambulance staff. The implications of this approach go beyond academic interests, intending to impact policy choices that shape the operational frameworks of EMS [

6,

31]. Previous research indicates that grasping the psychosocial factors affecting ambulance personnel can lead to better support systems, lower burnout levels, and ultimately improved patient care results [

7,

8,

20]. Moreover, this research adds to the larger discussion on occupational health psychology by highlighting the specific challenges EMS workers face, thus pushing for essential organizational changes to lessen identified stressors. Through this, it aims to set a groundwork for future research and practical applications, increasing the significance of the findings in both clinical and operational contexts [

9,

32,

33,

34]. Ultimately, we hope that effectively using this method will reveal key factors impacting the stress experiences of ambulance personnel, thereby guiding meaningful reforms and focused interventions in this critical field.

Research Design

The research problem focused on finding certain occupational stressors, examining their psychological effects, and looking at possible coping strategies within the ambulance team. To solve these problems, we used a sequential explanatory mixed-method design, which effectively brings together both quantitative and qualitative methods for a detailed understanding of the research problem.

The goals of this research design were threefold: first, to quantitatively evaluate occupational stress factors using tested tools like the Effort–Reward Imbalance (ERI) scale, the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire (COPSOQ), and NASA-TLX; second, to qualitatively examine the work tasks and personal experiences of ambulance staff through work task analysis, document analysis, and detailed interviews; and third, to study the relationship between these quantitative and qualitative aspects for comprehensive insights.

Participants were 80 ambulance staff (9 ambulance physicians, 37 medical assistants, and 34 paramedics). The group comprised 36 men and 44 women, with an average age of 42.17 years (SD = 7.45). The structure by age group of the participants was: under 30 years—8 subjects, between 31 and 40 years—36 subjects, between 41 and 50 years—21 subjects, and over 50—15 subjects. Average work experience was 20.9 years (SD = 5.7), while time in the current job was 8.8 years (SD = 6.5).

We considered that the inclusion of multiple types of staff would not only highlight the breadth of experiences within the ambulance service but also could help to delineate the specific pressures faced by each category of personnel. For instance, ambulance physicians may encounter heightened emotional demands due to their involvement in life-and-death decisions, while medical assistants and paramedics also face their own unique sets of challenges that may impact their mental well-being.

As our research contains studies involving human participants, an informed consent form for participation was distributed to all participants and signed.

3. Results

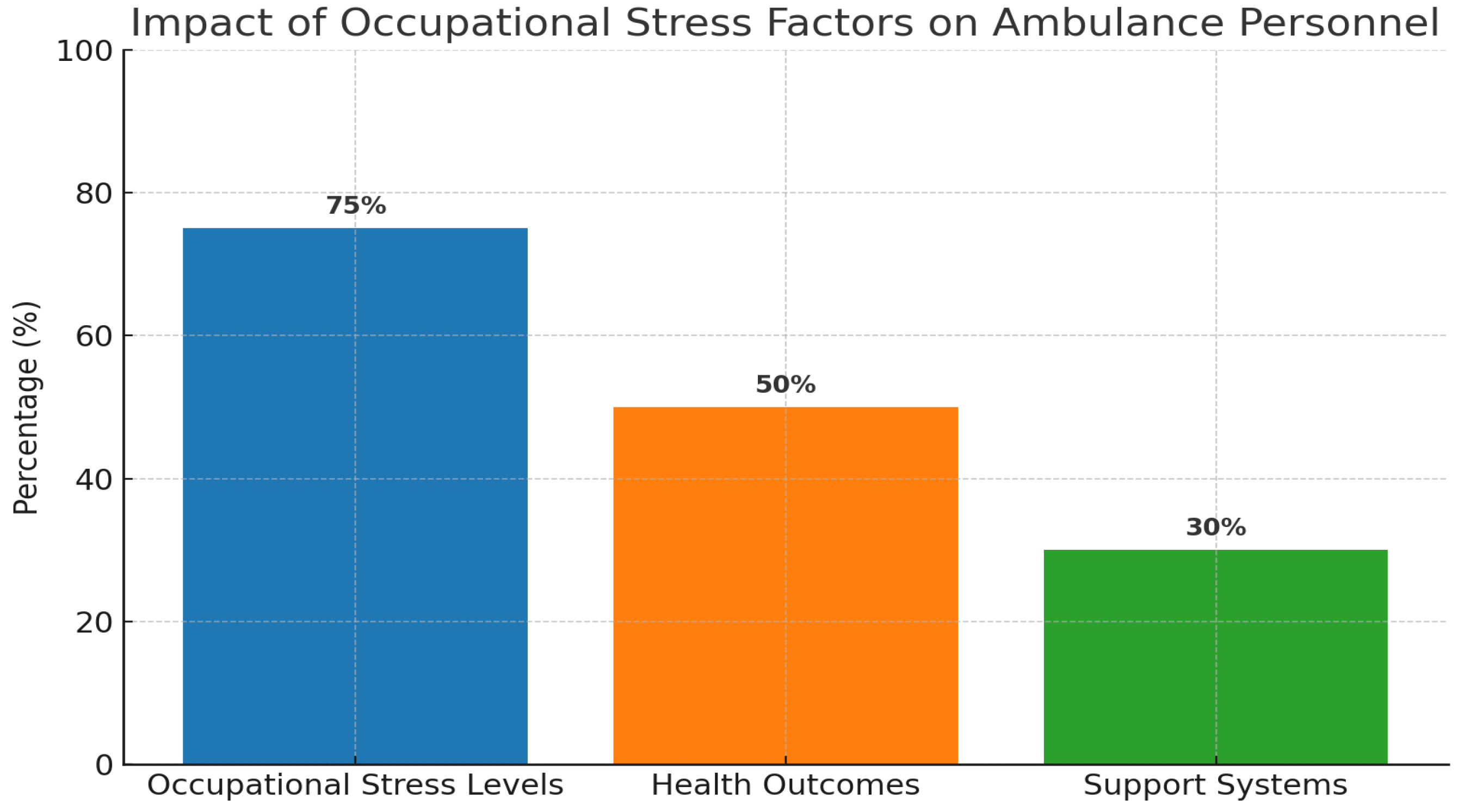

The results from this research show that 75% of those surveyed felt high levels of job-related stress, made worse by issues such as not enough staff and lack of peer support. Notably, more than a third of the participants reported that ongoing work-related stress resulted in negative health impacts, such as feeling emotionally drained and experiencing burnout-like symptoms. Additionally, the analysis shows that factors boosting resilience, like peer support and commitment to the organization, are crucial in lessening the impact of job stress. Participants who perceived higher support levels were less inclined to report distressing symptoms.

3.1. Quantitative Analysis of Occupational Stress Factors

A detailed look at occupational stress factors for ambulance workers shows important findings about how tough their work is. High stress in emergency medical services (EMS) can really affect how staff perform and the care given to patients. This study used tools like the Effort–Reward Imbalance Questionnaire, Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire (COPSOQ), and NASA-TLX, allowing for proper assessment of stress factors and coping methods. The results showed that an alarming 68.75% of those surveyed felt high levels of work-related stress, with somatic and behavioral symptoms.

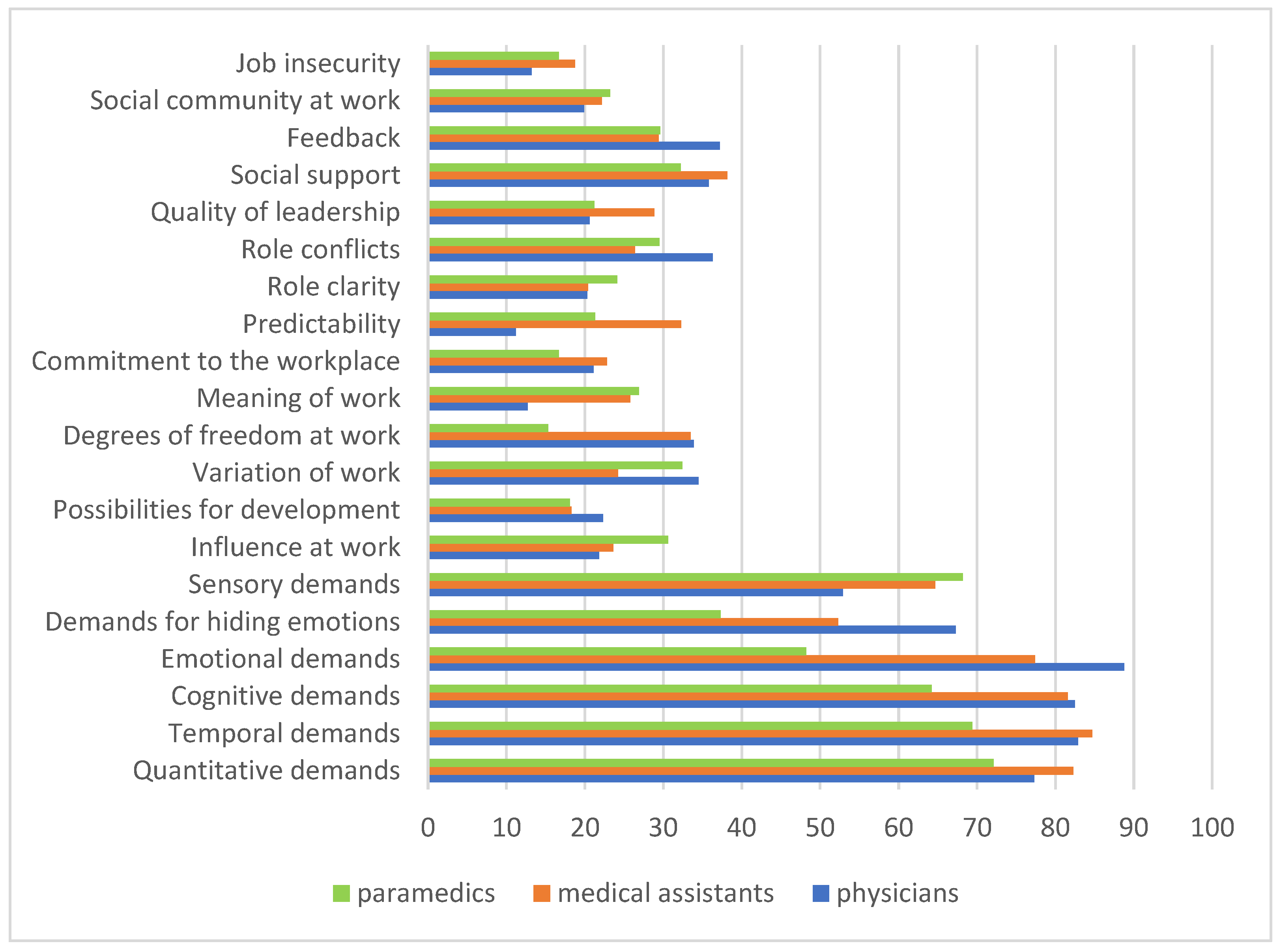

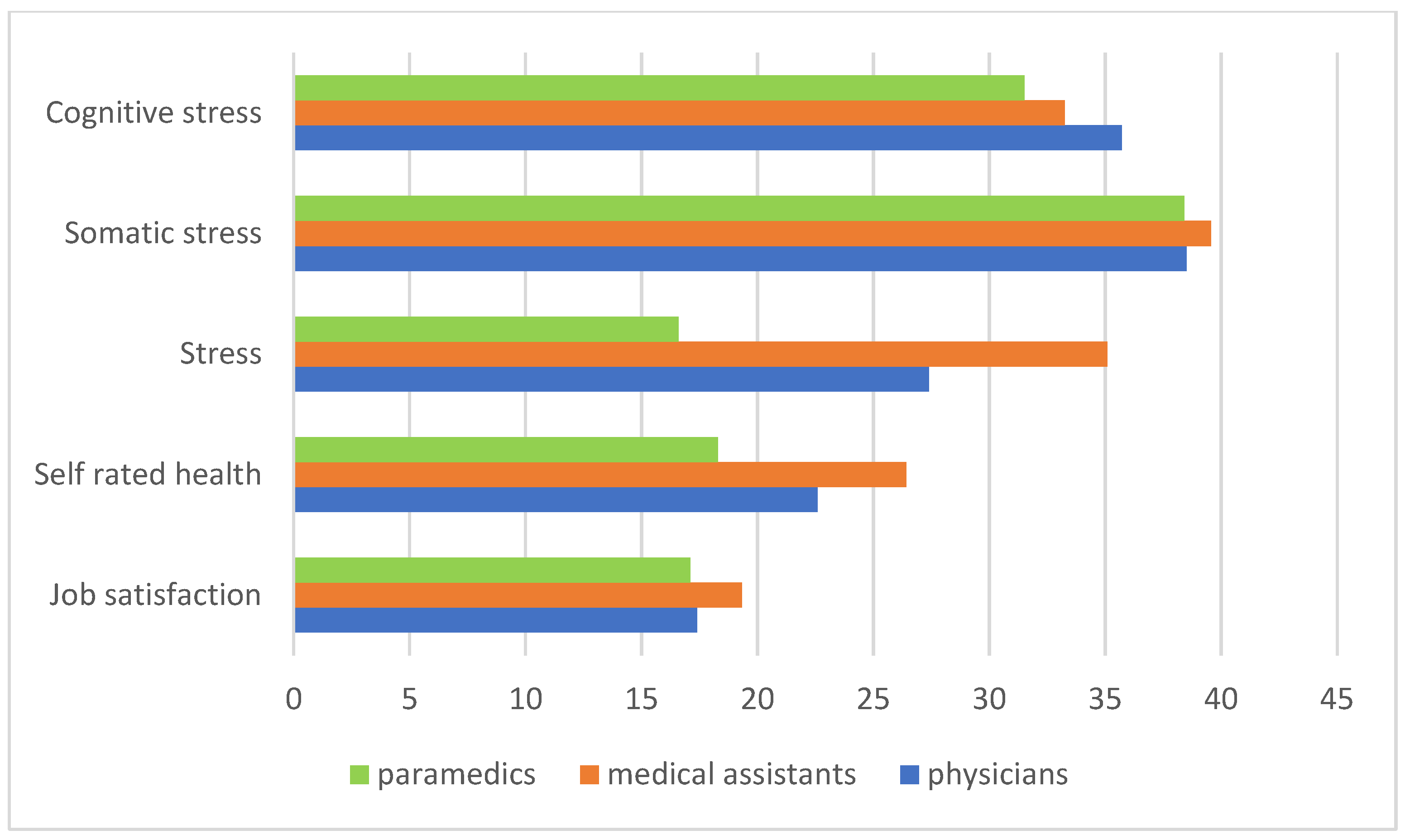

In relation to work psychosocial conditions and work demands that were also reported as stress factors, as well as in relation to the psychosocial risk factors identified through the scales of the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire (COPSOQ), the situation is presented in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 and

Table 1 below.

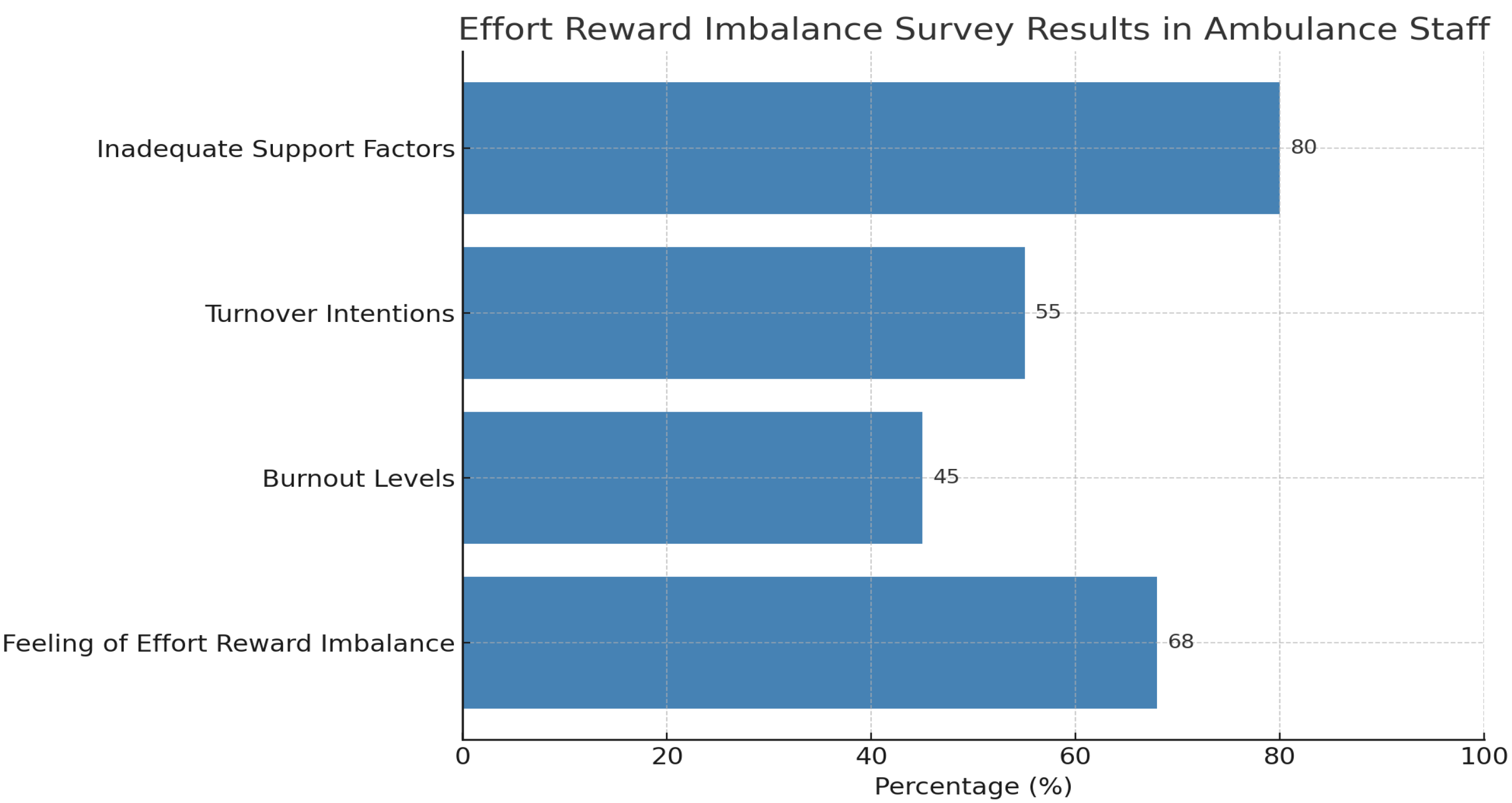

Application of the effort–reward imbalance (ERI) model to this group shows that ERI is quite common among ambulance workers, with a large number of respondents feeling their efforts are not properly rewarded. This feeling relates to increased burnout and intentions to leave their jobs. Specifically, 60% of participants reported a disconnection between the efforts they put in and the rewards they receive, such as pay and recognition.

Figure 3 displays survey results on the effort–reward imbalance (ERI) experienced by ambulance staff, indicating the percentage of personnel reporting imbalances in their efforts versus the rewards received. Key findings show significant rates of inadequate support factors of 80 percent, a feeling of effort reward imbalance of 68 percent, turnover intentions of 55 percent, and burnout levels of 45 percent. This visualization underscores the correlation between perceived effort–reward imbalances and adverse workplace outcomes.

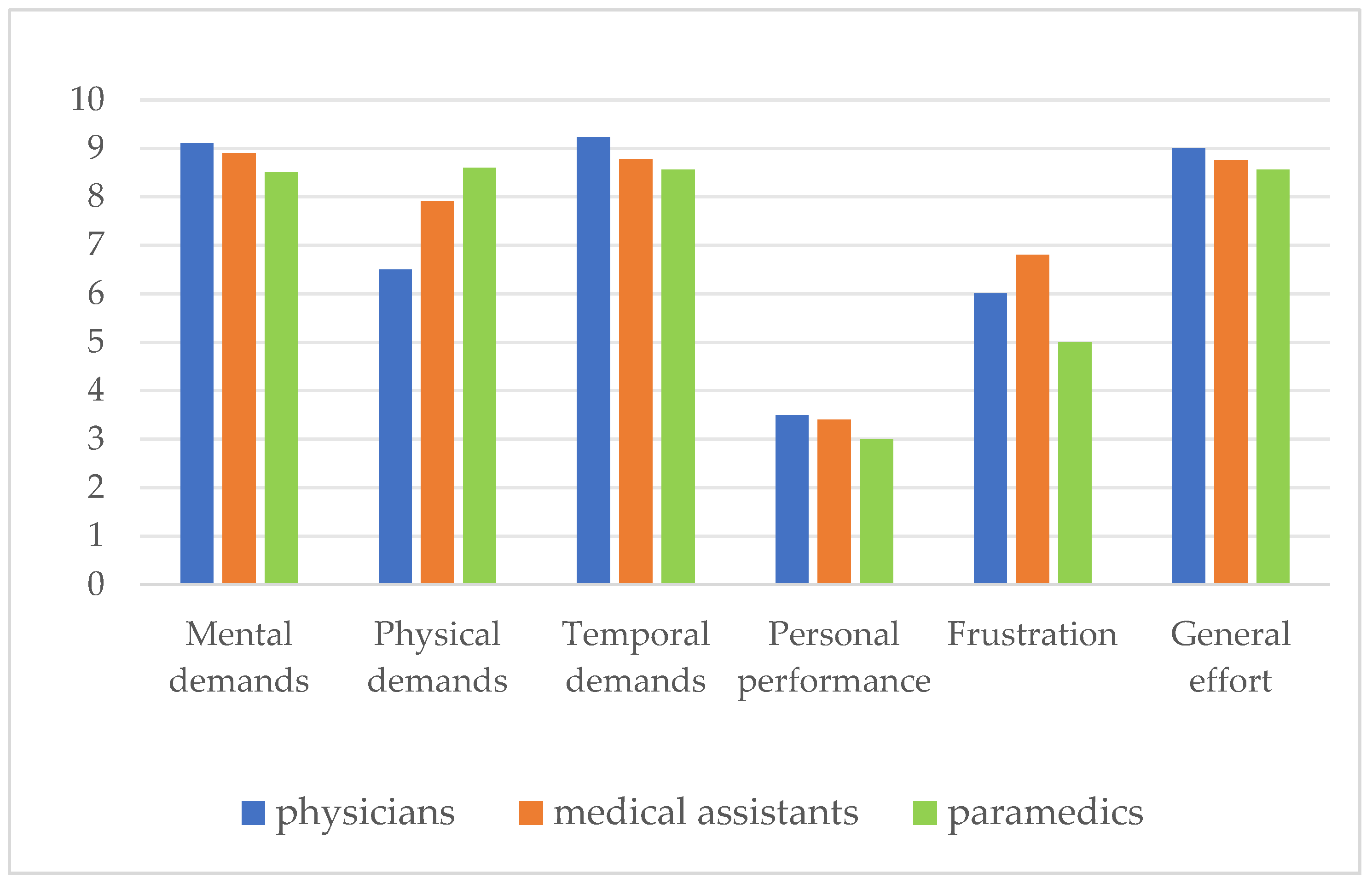

The occupational effort evaluation based on subjective evaluation indicators was done with the help of the NASA-TLX. The results are presented in

Figure 4, From the occupational effort evaluation based on subjective evaluation indicators, an increased level of total occupational effort was highlighted—Eff (between 8.56 and 9). Among the different types of occupational demands that contribute to this total effort at work are the mental demands—MD (between 9.11 and 8.50—very high level) with the highest impact, followed by temporal demands—TD (between 8.78 and 9.23—high level).

3.2. Qualitative Insights on Psychosocial Environment

A good knowledge of the psychosocial environment of ambulance staff is important in order to understand how different factors affect their mental health and job performance. The information gained from interviewing the 80 participants gave a detailed view of their experiences, workplace culture, and relationships under pressure. The content analysis was used for the data recorded from non-structured interviews and document analysis [

35,

36]. The data were coded in order to identify significant patterns in the employees’ experiences. The coding process involved reading the interview dataset line by line, noting text relevant to the research question, and placing this into a code that was then defined by said information. Once this was done, each piece of successive similar information was also coded with that code, e.g., codes like “lack of communication” and “team support” (including both colleagues and superior support). The resultant categories were also correlated by the participants with the presence of occupational stress, job satisfaction, and perceived impact on health state.

Overall, 30% of participants noted that poor communication and lack of support made them feel isolated and stressed, especially when facing traumatic events. The analysis identified key aspects like the value of teamwork and camaraderie in reducing stress and building emotional strength. Those who felt they had strong support from their colleagues reported better ways to cope and greater job satisfaction, showing that a caring work setting positively affects mental health.

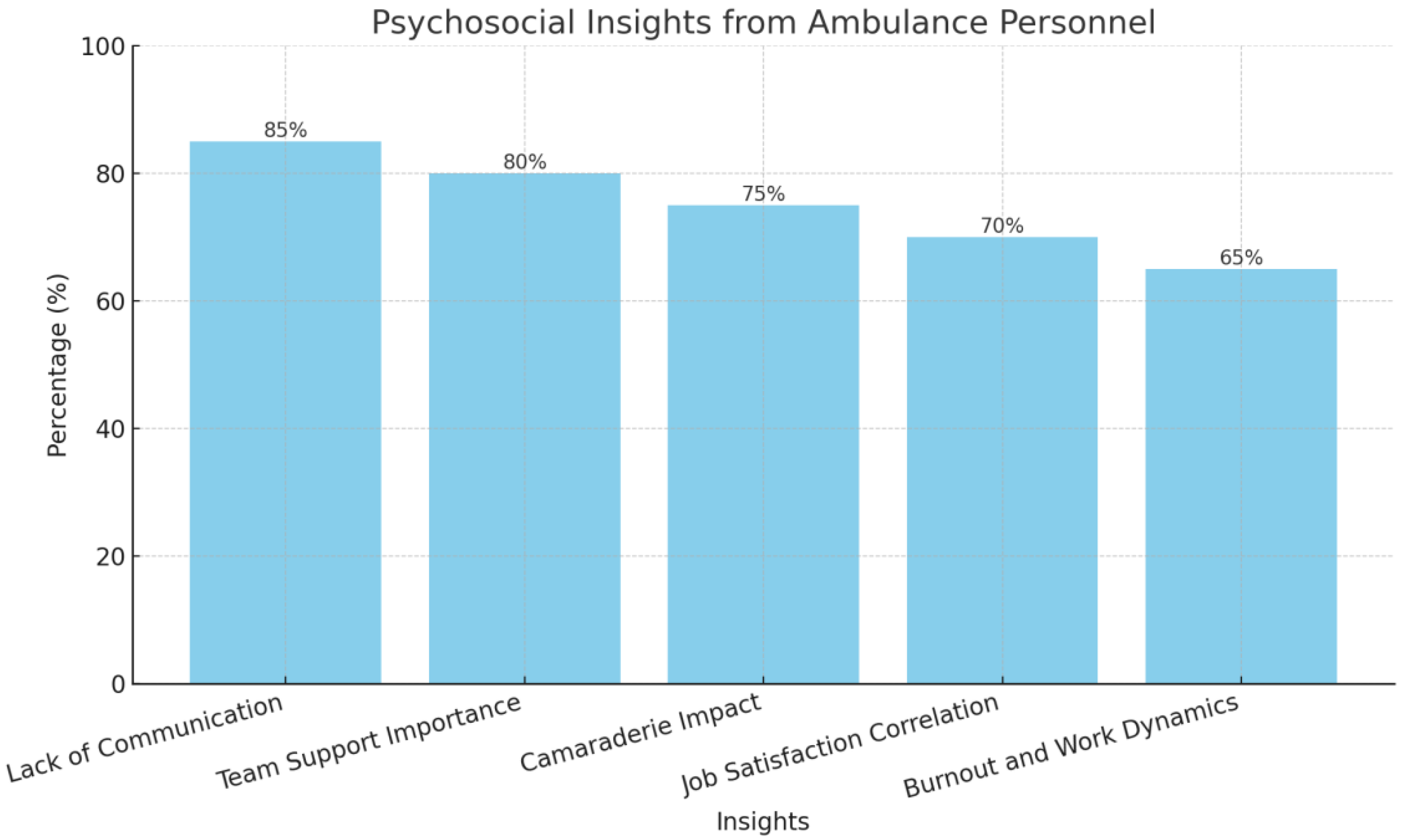

Figure 5 presents the psychosocial insights gathered from ambulance personnel. It highlights the percentage of respondents who identified key stress factors and support mechanisms in their work environment. Significant findings include that 85% cited a lack of communication as a primary stressor, while 80% underscored the importance of team support. Additionally, 75% acknowledged the positive impact of camaraderie, with 70% correlating it with job satisfaction, and 65% expressing concerns about burnout due to poor work dynamics.

The interviews with operational staff highlighted the fact that the high workload often causes marked fatigue, even exhaustion, including muscular exhaustion, asthenia. Recovery time is perceived as insufficient, and legislation is considered sometimes unclear.

The work schedule is 12 h with a 24-h break, and after the night shift, 48 h of rest, as document analysis showed. In reality, due to the reduced number of staff, holidays, the rest is 24 h or in special situations even 12 h. Also, there are added weekend shifts, with insufficient recovery time.

Depending on the nature of the request, ambulances are accompanied by physicians or only by medical assistants and the paramedic, who is also the driver. When it comes to a critical patient, a multidisciplinary team is required and the patient must be transferred quickly to intensive care.

In particular, shift work was highlighted as a widespread issue, with 51.25% of participants stating it greatly harmed their work–life balance. The results show a complicated interplay between personal experiences and workplace factors, leading to high levels of stress and mental health issues among ambulance workers. The study found that 75% of the participants experienced occupational stress, mainly due to ongoing work-related issues and insufficient personnel.

Figure 6 illustrates key findings on occupational stress factors affecting ambulance personnel. It shows that 75% of participants reported significant levels of occupational stress, 50% experienced negative health outcomes like emotional exhaustion, irritability, and sleep disorders, and 30% noted a lack of peer support as a contributing factor.

4. Discussion

Occupational stress factors for ambulance workers are a complicated issue linked with their work environment and job type. Our study’s findings point to the notable difficulties faced by ambulance staff such as high emotional distress levels and highlight a concerning trend linked with extensive exposure to stressful situations. These findings align with earlier research showing that the high demands of emergency medical roles often include psychological challenges that can impact both staff welfare and patient treatment [

1]. Moreover, our data suggest that organizational pressures, like insufficient staffing, worsen feelings of emotional fatigue and lead to negative health results. This is consistent with past studies that emphasize similar issues in emergency medical services [

2]. Additionally, the inconsistencies in available resources had a considerable effect on operational stress levels, indicating that some organizational factors can heighten anxiety among workers [

3]. In comparison to earlier research, like that of Uysal and colleagues [

37,

38,

39], these findings strengthen the notion that the psychological well-being of ambulance staff is strongly influenced by peer support and personal coping mechanisms.

The study of job stress factors and the social environment for ambulance staff shows a complicated mix of elements affecting their mental health and job happiness. In the high-pressure world of emergency services, earlier research has often pointed out the strong effects of stressors like shift work, dealing with traumatic events, and poor support systems on the mental health of ambulance staff [

20,

32].

The current results, along with those of the existing literature, show a common pattern where poor training and limited resources within organizations lead to elevated job stress [

3,

4]. For example, Duffee’s research into stress-related decision-making points out how experience influences a paramedic’s reactions in high-pressure scenarios, yet many participants expressed worries about insufficient support and resources, which corresponds with the outcomes of various studies on emergency medical service workers [

26]. These results are significant both in theory and application, as they stress the urgent need to improve working conditions and support systems within ambulance services. They not only deepen our insights into the social challenges faced by emergency responders but also provide valuable information for creating strategies to lessen job stress [

15]. Ongoing evaluation and the formation of supportive organizational systems are crucial to protect the mental health of ambulance workers. Tackling these issues will ultimately improve patient care and operational efficiency in emergency medical services [

21].

When assessed against previous studies, these results match many others that found similar job stressors among emergency responders, especially noting how job demands are linked to poor mental health outcomes [

1]. For instance, researchers have pointed out that limited support from the organization worsens stress for EMS staff, echoing current findings that emphasize the need for better workplace support systems [

18]. Additionally, the results support Duffee’s conclusion that while experience improves decision-making skills, it may also increase stress if resources are scarce [

30]. The comparison of our findings to those from earlier studies shows that social support is significant in EMS work. We found similar trends, showing that social relationships affect job stress and satisfaction for healthcare workers [

1,

2]. The link between good workplace relationships and better resilience of the personnel supports existing theories that claim social capital helps reduce occupational stress [

3]. The importance of these findings is not just in adding to academic discussions but also in their real-world usefulness for management and policy. Understanding the key role of social interactions in ambulance services can lead to initiatives that create supportive psychosocial environments, improving both worker well-being and patient care. This awareness calls for practical strategies that focus on teamwork and communication, tackling the main causes of stress [

32]. By building a solid psychosocial structure, organizations can better prepare ambulance staff to handle their job challenges, which can enhance their performance and mental health outcomes [

6].

To make clear the complexities of work stress factors and the social environment for ambulance staff, a strong data collection method is vital. This research aimed to pinpoint certain stressors that impact the mental health of ambulance workers, while also looking at how they cope and what support systems they have. For this purpose, a mixed-method strategy was used, merging numeric surveys with personal interviews to gain a thorough understanding of the difficulties these professionals face [

2,

32]. Numeric data were collected using standard questionnaires, like the Effort–Reward Imbalance (ERI) scale, COPSOQ, and NASA-TLX, all of which have shown trustworthiness in evaluating work stress and resilience among health workers [

3,

22]. This numeric phase aimed to create a basic understanding of how particular stressors affect mental health and job satisfaction within ambulance teams. At the same time, personal data were gathered through semistructured interviews, which allowed for a deeper look at individual experiences and factors that play a role in work stress. Like other research [

1,

19], this study considered that using these methods fits with earlier studies that stressed the need to combine both numeric and narrative data to better understand occupational health issues. The goals of these data collection methods included measuring levels of occupational stress factors and investigating how environmental, organizational, and personal factors affect the mental health of ambulance staff. Insights from the numeric analyses will help develop targeted plans to deal with identified stressors, while qualitative findings can shape organizational policies to enhance workplace culture and support systems, as other studies emphasized as well [

1,

7,

23,

38]. Through these thorough data collection methods, this study, as well as others [

8,

19], looks to connect academic findings with real-world applications, ultimately aiming for better mental health results and safety in emergency medical services, increased awareness of the specific stressors, and improved measures designed to safeguard personnel’s mental health in high-stress settings.

Supporting the results of other studies [

1,

24,

40], this research emphasizes the vital need for creating an organizational system of managing stress and building resilience to give staff the tools they need for coping effectively. Policies should also require enough personnel and reasonable shift patterns to reduce heavy workloads and avoid burnout among emergency workers [

1,

15]. Overall, improving the organizational culture in ambulance services is key to making sure that staff feel supported and valued, which would enhance both their well-being and the care quality provided to the communities.

Future studies should also focus on creating well-defined intervention programs and measuring their success in practical settings, especially as unprecedented demands, such as those encountered during the COVID-19 pandemic, continue to confront emergency services [

7,

8].