From Roots to Resilience: Exploring the Drivers of Indigenous Entrepreneurship for Climate Adaptation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

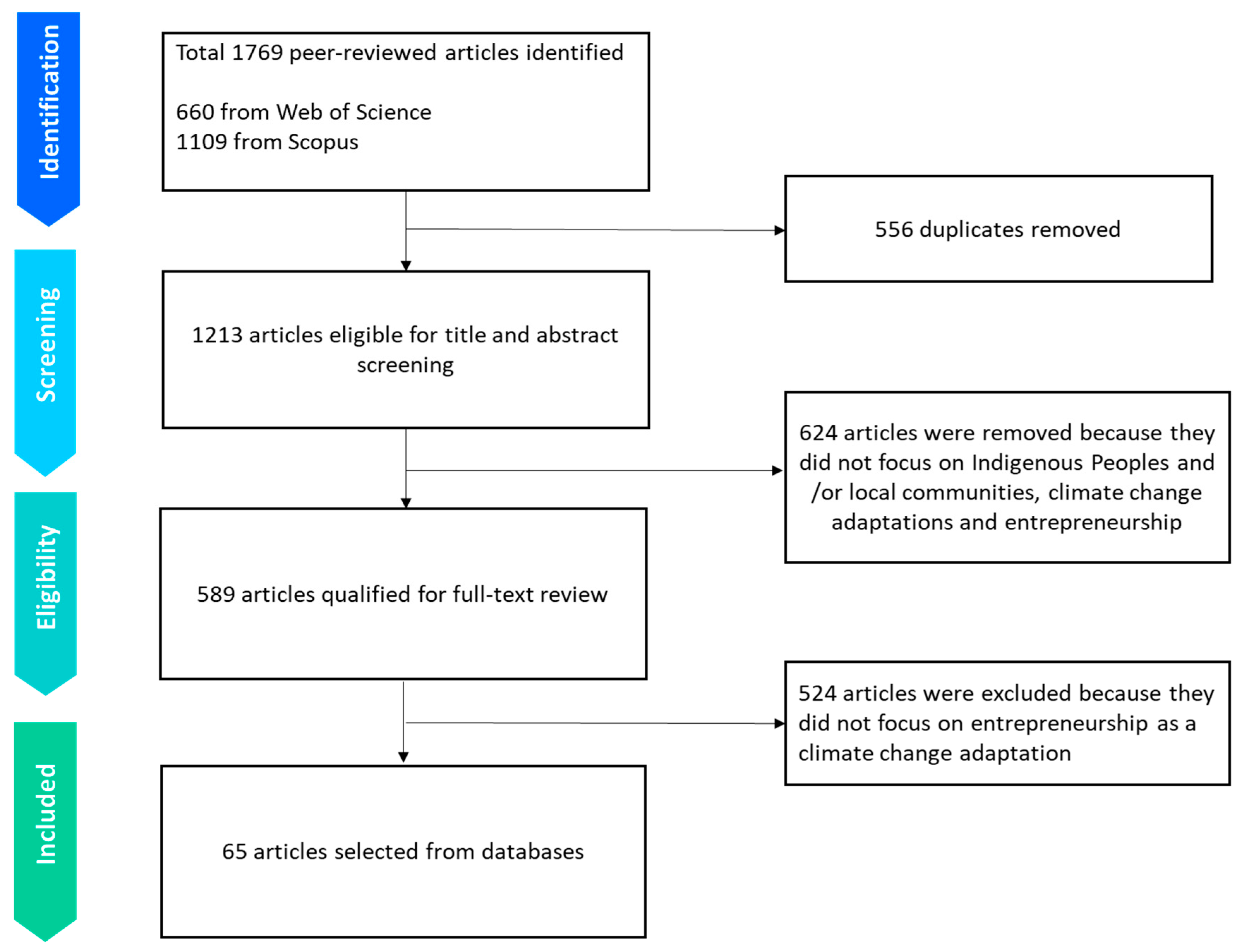

2.1. Step 1: Systematic Review

2.2. Step 2: Case Study Assessment

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Results

3.2. Drivers of Indigenous Entrepreneurship

3.3. Case Study Assessment

We [Vedda] only have 1.2 acres here [Henanigala]. However, when we [Vedda] used to live in ‘Dambana,’ we [Vedda] had 2 acres/household. When the government settled us [Vedda] down here [Henanigala], they [government officials] promised to give us [Vedda] land rights and access to the forest. But we [Vedda] got nothing (Respondent 04).

We [Vedda] start planting seeds around August and September. However, during that time, we [Vedda] do not get rain nowadays. So, we [Vedda] intentionally pass that dry period and then plant the seeds. We [Vedda] go for alternatives during that period, like collecting honey and timber, fishing, and home gardening (Respondent 05).

Cultivation is now seasonal due to weather changes. We [Vedda] cultivate for six months and rely on the harvest for the subsequent six months. In case of late rain, we [Vedda] hunt and collect honey until the rainfall allows us to resume cultivation (Respondent 01).

We [Vedda] all get together during the cultivation season and help each other in weed control since not all of us [Vedda] can afford to buy pesticides (Respondent 02).

We [Vedda] have a ‘Wariga Sabahawa’ (a tribal society), where seven Indigenous communities get together. Nearly ten representatives from each village go to ‘Dambana’ and present their community requirements to the leader. Last time, we [Vedda] informed him [Vedda leader] that we [Vedda] have restrictions on accessing the forest. Our leader agreed to provide us with an identity card mentioning that we [Vedda] are members of an Indigenous Community (Respondent 03).

I [Vedda] did not stay home during COVID; I [Vedda] roamed the village and the forest. I am [Vedda] not afraid because I [Vedda] chant and pray to the ghosts for a cure. Besides, staying home is not an option; I [Vedda] must earn a living. No one will feed my family otherwise (Respondent 06).

It was my idea to start the shop. I [Vedda] saved LKR 5000 (~USD 17) monthly as a daily wager and started the shop. Additionally, I [Vedda] secured a bank loan of LKR 100,000 (~USD 350) to support my business (Respondent 07).

4. Discussion

4.1. Indigenous Entrepreneurship as a Climate Adaptation Strategy

4.2. Contributions

4.3. Limitations

4.4. Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- de Block, D.; Feindt, P.H.; van Slobbe, E. Shaping conditions for entrepreneurship in climate change adaptation: A case study of an emerging governance arrangement in the Netherlands. Ecol. Soc. 2019, 24, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galappaththi, E.K.; Ford, J.D.; Bennett, E.M. Climate change and adaptation to social-ecological change: The case of indigenous people and culture-based fisheries in Sri Lanka. Clim. Chang. 2020, 162, 279–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attanapola, C.T.; Lund, R. Contested identities of indigenous people: Indigenization or integration of the Veddas in Sri Lanka. Singap. J. Trop. Geogr. 2013, 34, 172–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peredo, A.M.; Anderson, R.B. Indigenous entrepreneurship research: Themes and variations. In Developmental Entrepreneurship: Adversity, Risk, and Isolation; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2006; pp. 253–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tengeh, R.K.; Ojugbele, H.O.; Ogunlela, O.G. Towards a theory of indigenous entrepreneurship: A classic? Int. J. Entrep. Small Bus. 2022, 45, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peredo, A.M.; Anderson, R.B.; Galbraith, C.S.; Honig, B.; Dana, L.P. Towards a theory of indigenous entrepreneurship. Int. J. Entrep. Small Bus. 2004, 1, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Ratten, V.; Dana, L.-P. Gendered perspective of indigenous entrepreneurship. Small Enterp. Res. 2017, 24, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hindle, K.; Lansdowne, M. Brave spirits on new paths: Toward a globally relevant paradigm of indigenous entrepreneurship research. J. Small Bus. Entrep. 2005, 18, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R.B.; Honig, B.; Paredo, A.M. Communities in the global economy: Where social and indigenous entrepreneurship meet. In Entrepreneurship as Social Change; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dana, L.P.; Anderson, R.B. A multidisciplinary theory of entrepreneurship as a function of cultural perceptions of opportunity. In International Handbook of Research on Indigenous Entrepreneurship; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2007; Volume 1, pp. 595–603. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Mallén, I.; Fernández-Llamazares, Á.; Reyes-García, V. Unravelling local adaptive capacity to climate change in the Bolivian Amazon: The interlinkages between assets, conservation and markets. Clim. Chang. 2017, 140, 227–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, D. An examination of Indigenous Australian entrepreneurs. J. Dev. Entrep. 2003, 8, 133–151. [Google Scholar]

- Padilla-Meléndez, A.; Plaza-Angulo, J.J.; Del-Aguila-Obra, A.R.; Ciruela-Lorenzo, A.M. Indigenous entrepreneurship. Current issues and future lines. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2022, 34, 6–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrang-Ford, L.; Pearce, T.; Ford, J.D. Systematic review approaches for climate change adaptation research. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2015, 15, 755–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenack, K.; Stecker, R. A framework for analyzing climate change adaptations as actions. Mitig. Adapt. Strat. Glob. Chang. 2012, 17, 243–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, J.D.; Berrang-Ford, L.; Lesnikowski, A.; Barrera, M.; Heymann, S.J. How to Track Adaptation to Climate Change: A Typology of Approaches for National-Level Application. Ecol. Soc. 2013, 18, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamau, J.W.; Mwaura, F. Climate change adaptation and EIA studies in Kenya. Int. J. Clim. Change Strat. Manag. 2013, 5, 152–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, M.; Thomas, I. Synthesising case-study research—Ready for the next step? Environ. Educ. Res. 2012, 18, 751–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, J.H.; Synnot, A.; Turner, T.; Simmonds, M.; Akl, E.A.; McDonald, S.; Salanti, G.; Meerpohl, J.; MacLehose, H.; Hilton, J.; et al. Living systematic review: 1. Introduction—The why, what, when, and how. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2017, 91, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, M.T.; Moher, D. Systematic reviews deserve more credit than they get. Nat. Med. 2013, 19, 395–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nightingale, A. A guide to systematic literature reviews. Surgery 2009, 27, 381–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biesbroek, J.; Niesten, J.; Dankbaar, J.; Biessels, G.; Velthuis, B.; Reitsma, J.; van der Schaaf, I. Diagnostic Accuracy of CT Perfusion Imaging for Detecting Acute Ischemic Stroke: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2013, 35, 493–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, J.D.; Pearce, T. What we know, do not know, and need to know about climate change vulnerability in the western Canadian Arctic: A systematic literature review. Environ. Res. Lett. 2010, 5, 014008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Q.N.; Pluye, P. Systematic reviews: A brief historical overview. Educ. Inf. 2018, 34, 261–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengist, W.; Soromessa, T.; Legese, G. Method for conducting systematic literature review and meta-analysis for environmental science research. MethodsX 2020, 7, 100777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galappaththi, E.K.; Ford, J.D.; Bennett, E.M. A framework for assessing community adaptation to climate change in a fisheries context. Environ. Sci. Policy 2019, 92, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seelos, C.; Mair, J.; Battilana, J.; Tina, D.M. The Embeddedness of Social Entrepreneurship: Understanding Variation across Local Communities. In Communities and Organizations; Marquis, C., Lounsbury, M., Greenwood, R., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2011; Volume 33, pp. 333–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayashantha, P.; Johnson, N.W. Oral Health Status of the Veddas—Sri Lankan Indigenous People. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2016, 27, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, P.D.; Punchihewa, A.G. Socio-Anthropological Research Project on Vedda Community in Sri Lanka; University of Colombo: Colombo, Sri Lanka, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Dryzek, J.S.; Norgaard, R.B.; Schlosberg, D. The Oxford Handbook of Climate Change and Society; OUP Oxford: Oxford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Dearnley, C. A reflection on the use of semi-structured interviews. Nurse Res. 2005, 13, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meho, L.I. E-mail interviewing in qualitative research: A methodological discussion. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2006, 57, 1284–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temple, B.; Young, A. Qualitative Research and Translation Dilemmas. Qual. Res. 2004, 4, 161–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntosh, M.J.; Morse, J.M. Situating and Constructing Diversity in Semi-Structured Interviews. Glob. Qual. Nurs. Res. 2015, 2, 2333393615597674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husband, G. Ethical Data Collection and Recognizing the Impact of Semi-Structured Interviews on Research Respondents. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallio, H.; Pietilä, A.; Johnson, M.; Kangasniemi, M. Systematic methodological review: Developing a framework for a qualitative semi-structured interview guide. J. Adv. Nurs. 2016, 72, 2954–2965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J.C. Social Categorization and the Self-Concept: A Social Cognitive Theory of Group Behavior; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2010; p. 272. [Google Scholar]

- Mannan, D.K.A.; Mannan, K.A. Knowledge and Perception Towards Novel Coronavirus (COVID 19) in Bangladesh (SSRN Scholarly Paper 3576523). Int. Res. J. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2020, 6, 76–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu, R.; Reed, M.G. Adaptation through bricolage: Indigenous responses to long-term social-ecological change in the Saskatchewan River Delta, Canada. Can. Geogr. Can. 2018, 62, 437–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, S.A.; Busenitz, L.W. The entrepreneurship of resource-based theory. J. Manag. 2001, 27, 755–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J.B. Resource-based theories of competitive advantage: A ten-year retrospective on the resource-based view. J. Manag. 2001, 27, 643–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.M.; Nahiduzzaman; Wahab, A. Fisheries co-management in hilsa shad sanctuaries of Bangladesh: Early experiences and implementation challenges. Mar. Policy 2020, 117, 103955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korber, S.; McNaughton, R.B. Resilience and entrepreneurship: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2017, 24, 1129–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahaliyanaarachchi, R.; Elapata, M.; Esham, M.; Madhuwanthi, B. Agritourism as a sustainable adaptation option for climate change. Open Agric. 2019, 4, 737–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meek, W.R.; Pacheco, D.F.; York, J.G. The impact of social norms on entrepreneurial action: Evidence from the environmental entrepreneurship context. J. Bus. Ventur. 2010, 25, 493–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ado, A.M.; Leshan, J.; Savadogo, P.; Bo, L.; Shah, A.A. Farmers’ awareness and perception of climate change impacts: Case study of Aguie district in Niger. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2019, 21, 2963–2977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atela, J.; Gannon, K.E.; Crick, F. Climate Change Adaptation Among Female-Led micro, Small and Medium Enterprises in Semi-Arid Areas: A Case Study from Kenya. 2018. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10625/59287 (accessed on 25 July 2022).

- Hart, S. Adaptive Heuristics. Econometrica 2005, 73, 1401–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- York, J.G.; Venkataraman, S. The entrepreneur–environment nexus: Uncertainty, innovation, and allocation. J. Bus. Ventur. 2010, 25, 449–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwatsika, C. Entrepreneurship development and entrepreneurial orientation in rural areas in Malawi. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2015, 9, 425–436. [Google Scholar]

- Nurlaela, S.; Raya, A.B.; Hariadi, S.S. Information Technology Utilization Of Young Educated Farmers In Agricultural Entrepreneurship. Agro Èkon. 2022, 33, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, J. New Approaches to Revitalise Rural Economies and Communities—Reflections of a Policy Analyst. Eur. Countrys. 2016, 8, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kom, Z.; Nethengwe, N.S.; Mpandeli, N.S.; Chikoore, H. Determinants of small-scale farmers’ choice and adaptive strategies in response to climatic shocks in Vhembe District, South Africa. GeoJournal 2022, 87, 677–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFadgen, B.K. Connecting policy change, experimentation, and entrepreneurs: Advancing conceptual and empirical insights. Ecol. Soc. 2019, 24, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xenarios, S.; Kakumanu, K.R.; Nagothu, U.S.; Kotapati, G.R. Gender differentiated impacts from weather extremes: Insight from rural communities in South India. Environ. Dev. 2017, 24, 156–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skouloudis, A.; Tsalis, T.; Nikolaou, I.; Evangelinos, K.; Filho, W.L. Small & Medium-Sized Enterprises, Organizational Resilience Capacity and Flash Floods: Insights from a Literature Review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forino, G.; von Meding, J. Climate change adaptation across businesses in Australia: Interpretations, implementations, and interactions. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 18540–18555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirina, T.; Groot, A.; Shilomboleni, H.; Ludwig, F.; Demissie, T. Scaling Climate Smart Agriculture in East Africa: Experiences and Lessons. Agronomy 2022, 12, 820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanda, P.Z.; Mabhuye, E.B.; Mwajombe, A. Linking Coastal and Marine Resources Endowments and Climate Change Resilience of Tanzania Coastal Communities. Environ. Manag. 2023, 71, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burckhardt, P. A Strong Start-up Scene Flourishes in the Life Sciences Capital Basel. Chimia 2014, 68, 855–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, G.; Merrill, R.K.; Schillebeeckx, S.J.D. Digital Sustainability and Entrepreneurship: How Digital Innovations Are Helping Tackle Climate Change and Sustainable Development. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2021, 45, 999–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirnar, İ. The Specific Characteristics of Entrepreneurship Process in Tourism Industry. Selçuk Üniversitesi Sos. Bilim. Enstitüsü Derg. 2015, 34, 34. [Google Scholar]

- Stephan, U.; Uhlaner, L.M.; Stride, C. Institutions and social entrepreneurship: The role of institutional voids, institutional support, and institutional configurations. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2015, 46, 308–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Dreu, C.K.W. Social Conflict: The Emergence and Consequences of Struggle and Negotiation. In Handbook of Social Psychology, 1st ed.; Fiske, S.T., Gilbert, D.T., Lindzey, G., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harkes, I.; Drengstig, A.; Kumara, M.; Jayasinghe, J.; Huxham, M. Shrimp aquaculture as a vehicle for Climate Compatible Development in Sri Lanka. The case of Puttalam Lagoon. Mar. Policy 2015, 61, 273–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimbu, A.N.; Booyens, I.; Winchenbach, A. Livelihood Diversification Through Tourism: Identity, Well-being, and Potential in Rural Coastal Communities. Tour. Rev. Int. 2022, 26, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, M.A.; Rizwan, M.; Abbas, A.; Makhdum, M.S.A.; Kousar, R.; Nazam, M.; Samie, A.; Nadeem, N. A Quest for Livelihood Sustainability? Patterns, Motives and Determinants of Non-Farm Income Diversification among Agricultural Households in Punjab, Pakistan. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atieno, R. Formal and Informal Institutions’ Lending Policies and Access to Credit by Small-Scale Enterprises in Kenya: An Empirical Assessment. 2001. Available online: http://publication.aercafricalibrary.org/handle/123456789/446 (accessed on 20 July 2022).

- Ćumurović, A.; Hyll, W. Financial Literacy and Self-Employment. J. Consum. Aff. 2019, 53, 455–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, A.; Atterton, J. Exploring the contribution of rural enterprises to local resilience. J. Rural Stud. 2015, 40, 30–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynie, J.M.; Shepherd, D.A.; McMullen, J.S. An Opportunity for Me? The Role of Resources in Opportunity Evaluation Decisions. J. Manag. Stud. 2009, 46, 337–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senyard, J.; Baker, T.; Steffens, P.; Davidsson, P. Bricolage as a Path to Innovativeness for Resource-Constrained New Firms. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2014, 31, 211–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duguma, L.A.; Atela, J.; Ayana, A.N.; Alemagi, D.; Mpanda, M.; Nyago, M.; Minang, P.A.; Nzyoka, J.M.; Foundjem-Tita, D.; Ntamag-Ndjebet, C.N. Community forestry frameworks in sub-Saharan Africa and the impact on sustainable development. Ecol. Soc. 2018, 23, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederick, H. The emergence of biosphere entrepreneurship: Are social and business entrepreneurship obsolete? Int. J. Entrep. Small Bus. 2018, 34, 381–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sindhu, S.; Dahiya, S.; Siwach, P.; Panghal, A. Adoption of sustainable business practices by entrepreneurs: Modelling the drivers. World Rev. Entrep. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 17, 704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuckertz, A.; Berger, E.S.; Prochotta, A. Misperception of entrepreneurship and its consequences for the perception of entrepreneurial failure—The German case. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2020, 26, 1865–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atindana, S.A.; Fagbola, O.; Ajani, E.; Alhassan, E.H.; Ampofo-Yeboah, A. Coping with climate variability and non-climate stressors in the West African Oyster (Crassostrea tulipa) fishery in coastal Ghana. Marit. Stud. 2020, 19, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, N. Understanding social resilience to climate variability in primary enterprises and industries. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2010, 20, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, T.J.; McMullen, J.S. Toward a theory of sustainable entrepreneurship: Reducing environmental degradation through entrepreneurial action. J. Bus. Ventur. 2007, 22, 50–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäfer, M.; de Figueiredo, M.D.; Iran, S.; Jaeger-Erben, M.; Silva, M.E.; Lazaro, J.C.; Meißner, M. Imitation, adaptation, or local emergency?—A cross-country comparison of social innovations for sustainable consumption in Brazil, Germany, and Iran. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 284, 124740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, D.A.; Williams, T.A. Spontaneous Venturing: An Entrepreneurial Approach to Alleviating Suffering in the Aftermath of a Disaster; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Doern, R.; Williams, N.; Vorley, T. Special issue on entrepreneurship and crises: Business as usual? An introduction and review of the literature. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2019, 31, 400–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, C.; Christiaensen, L.; Sheahan, M.; Shimeles, A.; Reardon, B.M.; McCullough, E.; Dillon, B.; Christian, P. The structural transformation of rural Africa: On the current state of African food systems and rural nonfarm economies. Presented at the African Economic Research Consortium’s Bieannual Research Workshop, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 29 November–3 December 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Littunen, H.; Hyrsky, K. The Early Entrepreneurial Stage in Finnish Family and Nonfamily Firms. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2000, 13, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringhofer, L. Comparing Local Transitions Across The Developing World. In Fishing, Foraging and Farming in the Bolivian Amazon: On a Local Society in Transition; Ringhofer, L., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 199–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggs, E.M.; Watmough, G.R.; Hutton, C.W. Community-Level Environmental and Climate Change Adaptation Initiatives in Nawalparasi, Nepal. In Climate Change and the Sustainable Use of Water Resources; Filho, W.L., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 591–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curry, J.G. A Closer Look at Entrepreneurship and Attitude Toward Risk; Bowling Green State University: Bowling Green, OH, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Embry, E.; Jones, J.; York, J.G. Climate change and entrepreneurship. In Handbook of Inclusive Innovation; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2019; pp. 377–393. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, R.A.; Song, Y.; Townsend, D.M.; Stallkamp, M. Internationalization of entrepreneurial firms: Leveraging real options reasoning through affordable loss logics. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 133, 194–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Lent, W.; Hunt, R.A.; Lerner, D.A. Back to Which Future? Recalibrating the Time-Calibrated Narratives of Entrepreneurial Action to Account for Nondeliberative Dynamics. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2020, 49, 435–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argade, P.; Salignac, F.; Barkemeyer, R. Opportunity identification for sustainable entrepreneurship: Exploring the interplay of individual and context level factors in India. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2021, 30, 3528–3551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korsgaard, S.; Hunt, R.A.; Townsend, D.M.; Ingstrup, M.B. COVID-19 and the importance of space in entrepreneurship research and policy. Int. Small Bus. J. Res. Entrep. 2020, 38, 697–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welter, F. All you need is trust? A critical review of the trust and entrepreneurship literature. Int. Small Bus. J. Res. Entrep. 2012, 30, 193–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, N.J.; Lindsay, W.A.; Jordaan, A.; Hindle, K. Opportunity recognition attitudes of nascent indigenous entrepreneurs. Int. J. Entrep. Small Bus. 2006, 3, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, M.; Danis, W.M.; Mack, J.; Sayers, J. From principles to action: Community-based entrepreneurship in the Toquaht Nation. J. Bus. Ventur. 2020, 35, 106051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiles, T.H.; Vultee, D.M.; Gupta, V.K.; Greening, D.W.; Tuggle, C.S. The Philosophical Foundations of a Radical Austrian Approach to Entrepreneurship. J. Manag. Inq. 2010, 19, 138–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco, D.F.; York, J.G.; Hargrave, T.J. The Coevolution of Industries, Social Movements, and Institutions: Wind Power in the United States. Organ. Sci. 2014, 25, 1609–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelling, M.; High, C. Understanding adaptation: What can social capital offer assessments of adaptive capacity? Glob. Environ. Change 2005, 15, 308–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naji, A.A. Factors Influencing Entrepreneurship Development; Lebanese International University: Sana’a, Yemen, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Munoz, L. Forced to Entrepreneurship: Modeling the Factors Behind Necessity Entrepreneurship (SSRN Scholarly Paper 2461470). J. Bus. Entrep. 2010, 22, 37–53. [Google Scholar]

- Levitte, Y. Bonding Social Capital in Entrepreneurial Developing Communities—Survival Networks or Barriers? Community Dev. Soc. J. 2004, 35, 44–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langevang, T.; Namatovu, R.; Dawa, S. Beyond necessity and opportunity entrepreneurship: Motivations and aspirations of young entrepreneurs in Uganda. Int. Dev. Plan. Rev. 2012, 34, 439–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matlay, H. The impact of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial outcomes. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2008, 15, 382–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Database | Search String | Number of Articles |

|---|---|---|

| Web of Science | ((TS = ((climat*)AND(Chang*)AND(Adapt*)))AND TS = ((Entrepreneur*)OR(Intrapreneur*)OR(Enterprise*)OR(start-up*)OR(business*)OR(ventur*))) AND TS = ((Indigenous)OR(communit*)OR(local)OR(village)) | 660 |

| Scopus | (TITLE-ABS KEY ((climat*)AND(chang*)AND(adapt*))AND TITLE-ABS-KEY ((entrepreneur*)OR(intrapreneur *)OR(enterprise *)OR(start-up *)OR(business*)OR(ventur*))AND TITLE-ABS-KEY((Indigenous)OR(communit*)OR(local)OR(village))) | 1109 |

| Criteria | Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Language | Written only in English | Other languages (n = 24) |

| Type of literature | Peer-reviewed journal articles, including original research, editorials, commentaries, essays, and reports Review articles, meta-analyses, thesis, book chapters | Newspaper articles, blogs, protocols (studies that are not yet conducted) (n = 66) |

| Population | Studies that refer explicitly to Indigenous populations and local communities | Studies that refer to only non-Indigenous people or people with high social privilege (n = 556) |

| Who adapts | People (individuals or groups) | Any other non-human systems (n = 119) |

| Focus | Practical/empirical | Conceptual and theoretical models (n = 108) |

| Time | Present or past decades (after 2010) | Prehistoric, past (n = 18) |

| Responses | Adaptation responses associated with entrepreneurship | Responses not related to entrepreneurship (n = 257) |

| Themes | Drivers of Indigenous Entrepreneurship | Direction of Impact | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decrease Adaptive Capacity | Increase Adaptive Capacity | |||

| Place-based relationships | Resource stewardship | 1  |  10 10 | [11,39,40,41,42,43] |

| Territorial connections | 1  |  5 5 | [11,44,45] | |

| Environmental risk factors | 1  |  6 6 | [45,46,47,48,49] | |

| Intergenerational learning | Traditional knowledge transfer | 2  |  2 2 | [11,50,51] |

| Adaptation learning | 1  |  7 7 | [52,53,54,55] | |

| Collective experience | 0 |  5 5 | [11,42,52,56] | |

| Community institutions | Social networks | 0 |  9 9 | [52,55,57,58,59] |

| Institutional support | 1  |  8 8 | [60,61,62,63] | |

| Overcoming the agency–structure paradox | 3  |  4 4 | [11,52,64,65,66] | |

| Collective capacity | Access to information | 0 |  3 3 | [11,51,58,67] |

| Access to capital | 2  |  6 6 | [44,68,69,70] | |

| Community-oriented entrepreneurial traits | 0 |  7 7 | [11,45,61,67] | |

| Culturally aligned venture strategies | Indigenous business models | 0 |  3 3 | [55,67,70] |

| Traditional products | 1  |  2 2 | [11,45,51] | |

| Local market relationships | 1  |  3 3 | [48,55,65] | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dharmasiri, I.P.; Galappaththi, E.K.; Baird, T.D.; Bukvic, A.; Rijal, S. From Roots to Resilience: Exploring the Drivers of Indigenous Entrepreneurship for Climate Adaptation. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4472. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104472

Dharmasiri IP, Galappaththi EK, Baird TD, Bukvic A, Rijal S. From Roots to Resilience: Exploring the Drivers of Indigenous Entrepreneurship for Climate Adaptation. Sustainability. 2025; 17(10):4472. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104472

Chicago/Turabian StyleDharmasiri, Indunil P., Eranga K. Galappaththi, Timothy D. Baird, Anamaria Bukvic, and Santosh Rijal. 2025. "From Roots to Resilience: Exploring the Drivers of Indigenous Entrepreneurship for Climate Adaptation" Sustainability 17, no. 10: 4472. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104472

APA StyleDharmasiri, I. P., Galappaththi, E. K., Baird, T. D., Bukvic, A., & Rijal, S. (2025). From Roots to Resilience: Exploring the Drivers of Indigenous Entrepreneurship for Climate Adaptation. Sustainability, 17(10), 4472. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104472