Sustaining Talent: The Role of Personal Norms in the Relationship Between Green Practices and Employee Retention

Abstract

1. Introduction

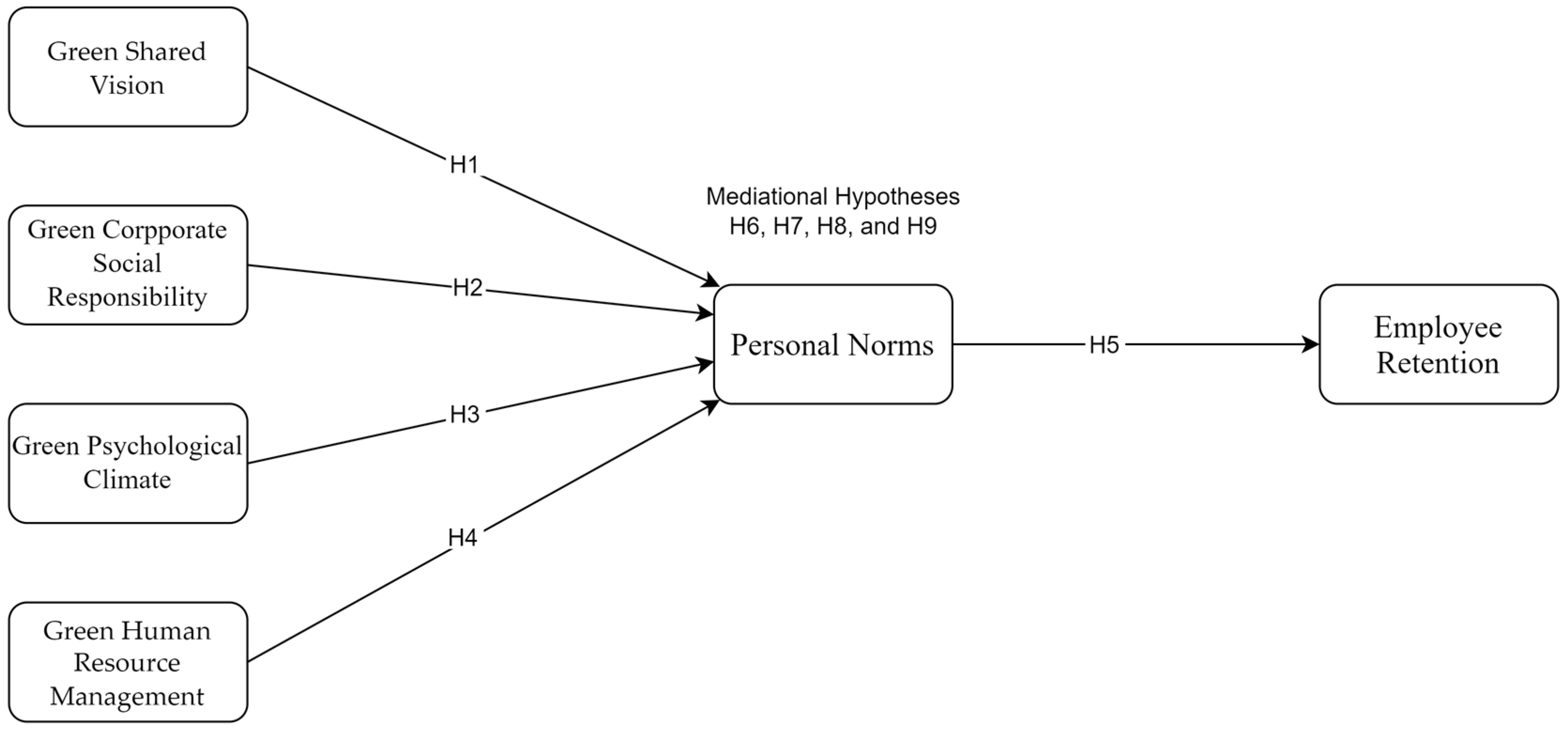

2. Theoretical Background and Development of Hypotheses

2.1. Theory of Planned Behaviour

2.2. Development of Hypotheses

2.2.1. Relationship Between Green Shared Vision and Personal Norms

2.2.2. Relationship Between Green Corporate Social Responsibility and Personal Norms

2.2.3. Relationship Between Green Psychological Climate and Personal Norms

2.2.4. Relationship Between Green Human Resource Management and Personal Norms

2.2.5. Relationship Between Personal Norms and Employee Retention

2.2.6. Mediating Role of Personal Norms in the Relationship Between Green Shared Vision and Employee Retention

2.2.7. Mediating Role of Personal Norms in the Relationship Between Green Corporate Social Responsibility and Employee Retention

2.2.8. Mediating Role of Personal Norms in the Relationship Between Green Psychological Climate and Employee Retention

2.2.9. Mediating Role of Personal Norms in the Relationship Between Green Human Resource Management and Employee Retention

3. Methods

3.1. Sample and Procedures

3.2. Measures

3.3. Common Method Bias

4. Data Analysis

4.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

4.2. Structural Equation Modeling

4.3. Measurement Model Analysis Results

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Contribution

5.2. Practical Contribution

5.3. Limitations and Future Direction

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GCSR | Green corporate social responsibility |

| GHRM | Green human resource management |

| SEM | Structural equation modeling |

| TPB | Theory of planned behavior |

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

| CMB | Common method bias |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| GSV | Green shared vision |

| GPC | Green psychological climate |

| PN | Personal norms |

| ER | Employee retention |

Appendix A

| Constructs | Measurement items | Sources |

| Green shared vision | GSV01: There is a commonality of environmental goals in my organization. | [41] |

| GSV02: There is a total agreement on my organization’s strategic environmental direction. | ||

| GSV03: Organization’s employees are committed to the environmental strategies of my organization. | ||

| GSV04: My organization’s employees are enthusiastic about the collective environmental mission of the organization. | ||

| Green corporate social responsibility | GCSR01: My organization participates in activities which aim to protect and improve the quality of the natural environment. | [42] |

| GCSR02: My organization makes investments to create a better life for the future generations. | ||

| GCSR03: My organization implements special programs to minimize its negative impact on the natural environment. | ||

| GCSR04: My organization targets sustainable growth which considers future generations. | ||

| Green human resource management | GHRM01: My organization sets green goals for its employees. | [26] |

| GHRM02: My organization provides employees with green training to promote green values. | ||

| GHRM03: My organization provides employees with green training to develop employees’ knowledge and skills required for green management. | ||

| GHRM04: My organization considers employees’ workplace green behavior in performance appraisals. | ||

| GHRM05: My organization relates employees’ workplace green behaviors to rewards and compensation. | ||

| GHRM06: My organization considers employees’ workplace green behaviors in promotion. | ||

| Green psychological climate | GPC01: My organization is worried about its environmental impact. | [43] |

| GPC02: My organization is interested in supporting environmental causes. | ||

| GPC03: My organization believes it is important to protect the environment. | ||

| GPC04: My organization is concerned with becoming more environmentally friendly. | ||

| GPC05: My organization would like to be seen as environmentally friendly. | ||

| Personal norms | PN01: I feel a moral obligation to protect the environment. | [44] |

| PN02: I feel that I should protect the environment. | ||

| PN03: I feel it is important that people in general protect the environment. | ||

| PN04: Because of my own values/principles, I feel an obligation to behave in an environmentally friendly way. | ||

| Employee retention | ER01: I would like to leave my present organization ® | [45] |

| ER02: I plan to leave my present organization as soon as possible ® | ||

| ER03: I plan to stay with my present organization as long as possible. | ||

| ER04: Under no circumstances would I voluntarily leave my present organization. |

References

- Kumar, R.; Rehman, U.U.; Phanden, R.K. Strengthening the social performance of Indian SMEs in the digital era: A fuzzy DEMATEL analysis of enablers. TQM J. 2024, 36, 139–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandita, D.; Ray, S. Talent management and employee engagement—A meta-analysis of their impact on talent retention. Ind. Commer. Train. 2018, 50, 185–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Wider, W.; Ye, G.; Tee, M.; Hye, A.K.M.; Lee, A.; Tanucan, J.C.M. Exploring the factors of employee turnover intentions in private education institutions in China: A Delphi study. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2024, 11, 2413915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, S.I.; Jamil, S.; Zaman, S.A.A.; Jiang, Y. Engaging the Modern Workforce: Bridging the Gap Between Technology and Individual Factors. J. Knowl. Econ. 2025, 16, 412–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, M.A.; Jianguo, D.; Junaid, M. Impact of green HRM practices on sustainable performance: Mediating role of green innovation, green culture, and green employees’ behavior. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 88524–88547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huo, X.; Azhar, A.; Rehman, N.; Majeed, N. The Role of Green Human Resource Management Practices in Driving Green Performance in the Context of Manufacturing SMEs. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stren, P.C. Toward a coherent theory of environmentally significant behaviour. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, G.; Naz, F. HR audit is a tool for employee retention and organisational citizenship behaviour: A mediating role of effective HR strategies in services sector of emerging economies. Middle East J. Manag. 2023, 10, 98–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, N.T.; Tučková, Z.; Jabbour, C.J.C. Greening the hospitality industry: How do green human resource management practices influence organizational citizenship behavior in hotels? A mixed-methods study. Tour. Manag. 2019, 72, 386–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Yin, H.; Liu, J.; Lai, K.-H. How is Employee Perception of Organizational Efforts in Corporate Social Responsibility Related to Their Satisfaction and Loyalty Towards Developing Harmonious Society in Chinese Enterprises? Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2014, 21, 28–40. [Google Scholar]

- Rafiq, M.; Dastane, O.; Mushtaq, R. Waste reduction as ethical behaviour: A bibliometric analysis and development of future agenda. J. Glob. Responsib. 2023, 14, 360–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrukh, M.; Rafiq, M.; Raza, A.; Ansari, N.Y. Climate change needs behavior change: A team mechanism of team green creative behavior. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2024, 36, 1577–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupp, D.E.; Mallory, D.B. Corporate social responsibility: Psychological, person-centric, and progressing. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2015, 2, 211–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 32, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. Normative Influences on Altruism. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; I am indebted to L. Berkowitz, R. Dienstbier, H. Schuman, R. Simmons, and R. Tessler for their thoughtful comments on an early draft of this chapter; Berkowitz, L., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1977; Volume 10, pp. 221–279. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, J.P.; Allen, N.J. A three-component conceptualization of organizational commitment. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 1991, 1, 61–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerci, M.; Longoni, A.; Luzzini, D. Translating stakeholder pressures into environmental performance—The mediating role of green HRM practices. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2016, 27, 262–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-S.; Chang, C.-H.; Yeh, S.-L.; Cheng, H.-I. Green shared vision and green creativity: The mediation roles of green mindfulness and green self-efficacy. Qual. Quant. 2015, 49, 1169–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.K.; Del Giudice, M.; Chierici, R.; Graziano, D. Green innovation and environmental performance: The role of green transformational leadership and green human resource management. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2020, 150, 119762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.T. How do corporate social responsibility and green innovation transform corporate green strategy into sustainable firm performance? J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 362, 132228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olbrich, R.; Quaas, M.F.; Baumgärtner, S. Personal norms of sustainability and farm management behavior. Sustainability 2014, 6, 4990–5017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabokro, M.; Masud, M.M.; Kayedian, A. The effect of green human resources management on corporate social responsibility, green psychological climate and employees’ green behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 313, 127963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansson, J.; Nordlund, A.; Westin, K. Examining drivers of sustainable consumption: The influence of norms and opinion leadership on electric vehicle adoption in Sweden. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 154, 176–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, T.A.; Zacher, H.; Parker, S.L.; Ashkanasy, N.M. Bridging the gap between green behavioral intentions and employee green behavior: The role of green psychological climate. J. Organ. Behav. 2017, 38, 996–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, D.D.T.; Paillé, P. Green recruitment and selection: An insight into green patterns. Int. J. Manpow. 2020, 41, 258–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumont, J.; Shen, J.; Deng, X. Effects of green HRM practices on employee workplace green behavior: The role of psychological green climate and employee green values. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2017, 56, 613–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholami, H.; Rezaei, G.; Saman, M.Z.M.; Sharif, S.; Zakuan, N. State-of-the-art Green HRM System: Sustainability in the sports center in Malaysia using a multi-methods approach and opportunities for future research. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 124, 142–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamil, S.; Zaman, S.I.; Kayikci, Y.; Khan, S.A. The role of green recruitment on organizational sustainability performance: A study within the context of green human resource management. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thøgersen, J. Norms for environmentally responsible behaviour: An extended taxonomy. J. Environ. Psychol. 2006, 26, 247–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harland, P.; Staats, H.; Wilke, H.A.M. Explaining proenvironmental intention and behavior by personal norms and the Theory of Planned Behavior 1. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 29, 2505–2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawehinmi, O.; Yusliza, M.Y.; Mohamad, Z.; Noor Faezah, J.; Muhammad, Z. Assessing the green behaviour of academics: The role of green human resource management and environmental knowledge. Int. J. Manpow. 2020, 41, 879–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younas, N.; Hossain, M.B.; Syed, A.; Ejaz, S.; Ejaz, F.; Jagirani, T.S.; Dunay, A. Green shared vision: A bridge between responsible leadership and green behavior under individual green values. Heliyon 2023, 9, e21511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, E.Y.; Sung, Y.H. Luxury and sustainability: The role of message appeals and objectivity on luxury brands’ green corporate social responsibility. J. Mark. Commun. 2022, 28, 291–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Werff, E.; Taufik, D.; Venhoeven, L. Pull the plug: How private commitment strategies can strengthen personal norms and promote energy-saving in the Netherlands. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2019, 54, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.K.; Biswas, S.R.; Abdul Kader Jilani, M.M.; Uddin, M.A. Corporate environmental strategy and voluntary environmental behavior—Mediating effect of psychological green climate. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawehinmi, O.; Yusliza, M.-Y.; Wan Kasim, W.Z.; Mohamad, Z.; Sofian Abdul Halim, M.A. Exploring the interplay of green human resource management, employee green behavior, and personal moral norms. Sage Open 2020, 10, 2158244020982292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.P.; Shree, S. Examining the effect of employee green involvement on perception of corporate social responsibility: Moderating role of green training. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2019, 30, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, T.; Baum, T.; Pine, R. Subjective norms: Effects on job satisfaction. Ann. Tour. Res. 2003, 30, 160–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vesely, S.; Klöckner, C.A.; Carrus, G.; Tiberio, L.; Caffaro, F.; Biresselioglu, M.E.; Kollmann, A.C.; Sinea, A.C. Norms, prices, and commitment: A comprehensive overview of field experiments in the energy domain and treatment effect moderators. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 967318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, L.; Kucukusta, D.; Chan, X. Employee turnover intention in travel agencies: Analysis of controllable and uncontrollable factors. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2015, 17, 577–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, J.J.P.; George, G.; Van den Bosch, F.A.J.; Volberda, H.W. Senior Team Attributes and Organizational Ambidexterity: The Moderating Role of Transformational Leadership. J. Manag. Stud. 2008, 45, 982–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, M.; Qu, Y.; Javed, S.A.; Zafar, A.U.; Rehman, S.U. Relation of environment sustainability to CSR and green innovation: A case of Pakistani manufacturing industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 253, 119938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, T.A.; Zacher, H.; Ashkanasy, N.M. Organisational sustainability policies and employee green behaviour: The mediating role of work climate perceptions. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 38, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onwezen, M.C.; Antonides, G.; Bartels, J. The Norm Activation Model: An exploration of the functions of anticipated pride and guilt in pro-environmental behaviour. J. Econ. Psychol. 2013, 39, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-W.; Price, J.L.; Mueller, C.W.; Watson, T.W. The Determinants of Career Intent Among Physicians at a U.S. Air Force Hospital. Hum. Relations 1996, 49, 947–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozionelos, N.; Simmering, M.J. Methodological threat or myth? Evaluating the current state of evidence on common method variance in human resource management research. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2022, 32, 194–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerson, K.; Damaske, S. The Science and Art of Interviewing; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, P.J.; Troth, A.C. Common method bias in applied settings: The dilemma of researching in organizations. Aust. J. Manag. 2020, 45, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, F.; Berbekova, A.; Assaf, A.G. Understanding and managing the threat of common method bias: Detection, prevention and control. Tour. Manag. 2021, 86, 104330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knief, U.; Forstmeier, W. Violating the normality assumption may be the lesser of two evils. Behav. Res. Methods 2021, 53, 2576–2590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zibarras, L.D.; Coan, P. HRM practices used to promote pro-environmental behavior: A UK survey. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2015, 26, 2121–2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramalho Luz, C.M.D.; Luiz de Paula, S.; de Oliveira, L.M.B. Organizational commitment, job satisfaction and their possible influences on intent to turnover. Rev. Gestão 2018, 25, 84–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographic Characteristic | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 47.5 |

| Female | 52.5 | |

| Age | Below 26 years | 19.0 |

| 26 to 30 years | 24.3 | |

| 31 to 35 years | 25.5 | |

| 36 to 45 years | 21.7 | |

| 46 to 60 years | 9.50 | |

| Education level | Certificate | 11.4 |

| Diploma | 22.8 | |

| Bachelor | 33.1 | |

| Masters | 22.1 | |

| Others | 10.6 | |

| Job level | Non-executive | 22.8 |

| Executive | 28.5 | |

| Current organization | Below 1 year | 17.5 |

| 1 to 3 years | 30.4 | |

| 3 to 7 years | 35.9 | |

| 7 to 15 years | 17.1 |

| Mean | SD | ER | GSV | GCSR | GSC | GHRM | PN | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ER | 2.975 | 0.910 | 1 | |||||

| GSV | 3.225 | 1.016 | 0.370 | 1 | ||||

| GCSR | 3.188 | 0.914 | 0.403 | 0.604 | 1 | |||

| GPC | 3.264 | 0.945 | 0.316 | 0.563 | 0.662 | 1 | ||

| GHRM | 3.222 | 0.25 | 0.314 | 0.554 | 0.598 | 0.619 | 1 | |

| PN | 3.289 | 1.035 | 0.432 | 0.492 | 0.503 | 0.459 | 0.390 | 1 |

| Constructs | Items | Loading | Cronbach’s Alpha | Composite Reliability (CR) | Average Variance Extracted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Green shared vision | GSV1 | 0.846 | 0.769 | 0.850 | 0.588 |

| GSV2 | 0.785 | ||||

| GSV3 | 0.755 | ||||

| GSV4 | 0.671 | ||||

| Green corporate social responsibility | GCSR1 | 0.768 | 0.729 | 0.831 | 0.552 |

| GCSR2 | 0.741 | ||||

| GCSR3 | 0.750 | ||||

| GCSR4 | 0.711 | ||||

| Green psychological climate | GPC1 | 0.696 | 0.792 | 0.857 | 0.546 |

| GPC2 | 0.779 | ||||

| GPC3 | 0.760 | ||||

| GPC4 | 0.779 | ||||

| GPC5 | 0.675 | ||||

| Green human resource | GHRM1 | 0.723 | 0.817 | 0.867 | 0.522 |

| GHRM2 | 0.696 | ||||

| GHRM3 | 0.702 | ||||

| GHRM4 | 0.765 | ||||

| GHRM5 | 0.682 | ||||

| GHRM6 | 0.765 | ||||

| Personal norms | PN1 | 0.820 | 0.798 | 0.868 | 0.623 |

| PN2 | 0.771 | ||||

| PN3 | 0.798 | ||||

| PN4 | 0.766 | ||||

| Employee retention | ER1 | 0.688 | 0.691 | 0.811 | 0.519 |

| ER2 | 0.753 | ||||

| ER3 | 0.714 |

| ER | GCSR | GHRM | GPC | GSV | PN | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ER | 0.720 | |||||

| GSCR | 0.415 | 0.743 | ||||

| GHRM | 0.339 | 0.597 | 0.723 | |||

| GPC | 0.331 | 0.658 | 0.615 | 0.739 | ||

| GSV | 0.400 | 0.604 | 0.554 | 0.567 | 0.767 | |

| PN | 0.441 | 0.501 | 0.393 | 0.461 | 0.504 | 0.789 |

| ER | GCSR | GHRM | GPC | GSV | PN | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ER | - | |||||

| GCSR | 0.577 | - | ||||

| GHRM | 0.434 | 0.772 | - | |||

| GPC | 0.439 | 0.868 | 0.771 | - | ||

| GSV | 0.514 | 0.808 | 0.696 | 0.719 | - | |

| PN | 0.585 | 0.651 | 0.482 | 0.575 | 0.619 | - |

| Hypotheses | Relationship | β | SD | t Values | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | GSV ≥ PN | 0.275 | 0.082 | 3.333 | Support |

| H2 | GSCR ≥ PN | 0.233 | 0.095 | 2.449 | Support |

| H3 | GPC ≥ PN | 0.143 | 0.096 | 1.498 | No support |

| H4 | GHRM ≥ PN | 0.013 | 0.092 | 0.146 | No support |

| H5 | PN ≥ ER | 0.441 | 0.054 | 8.148 | Support |

| H6 | GSV > PN ≥ ER | 0.121 | 0.040 | 3.014 | Support |

| H7 | GCSR > PN ≥ ER | 0.103 | 0.046 | 2.217 | Support |

| H8 | GPC > PN ≥ ER | 0.063 | 0.044 | 1.440 | No support |

| H9 | GHRM > PN ≥ ER | 0.006 | 0.042 | 0.142 | No support |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ding, W.; Rafiq, M. Sustaining Talent: The Role of Personal Norms in the Relationship Between Green Practices and Employee Retention. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4471. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104471

Ding W, Rafiq M. Sustaining Talent: The Role of Personal Norms in the Relationship Between Green Practices and Employee Retention. Sustainability. 2025; 17(10):4471. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104471

Chicago/Turabian StyleDing, Weichao, and Muhammad Rafiq. 2025. "Sustaining Talent: The Role of Personal Norms in the Relationship Between Green Practices and Employee Retention" Sustainability 17, no. 10: 4471. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104471

APA StyleDing, W., & Rafiq, M. (2025). Sustaining Talent: The Role of Personal Norms in the Relationship Between Green Practices and Employee Retention. Sustainability, 17(10), 4471. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104471