1. Introduction

Wisdom, as a psychological construct, has been viewed as a primary human virtue related to good judgment in the face of uncertainty. It relies on a different way of seeing and understanding life and one’s place in it. It has a direct effect on how you perceive, understand, coordinate and integrate with others. It is also a constructive approach to social conflicts between groups or individuals whether they are friends or foes, rivals or partners. This perception, in turn, reflects on how “conflicts could be resolved or what the actors might do” [

1], which constitutes the core of wisdom [

2]. Wisdom has been the subject of scientific inquiry at an individual level. Acknowledging the hyper-turbulent business environment, social scientists have conducted extensive research focusing on leadership and managerial wisdom. However, wisdom on the individual level may contribute to and even determine the outcome of international and societal conflicts, which, if not settled, have extremely sad and dire consequences. Based on this approach, the basic attributes of wisdom can be a key ingredient in dissolving the nearly half-century-long Cyprus conflict, which is contentious and accompanied by a high level of emotional involvement. This conflict has been shaped by the tremendous pressures of nationality, religion, race, and culture. It is a typical ‘messy situation’ [

3] in which stakeholders interpret problems differently, purposes are poorly defined, and deep conflicts exist about possible solutions. In this landscape, the wisdom level of individuals may be the key component for a sustainable solution. Wisdom provides the ability to understand the issues from multiple perspectives, enhances the capacity for moral reasoning, and fosters the possibility of seeking and finding creative and novel solutions. A focus on followers’ perceptions and their effect on leadership decisions is not new [

4]. However, the impact of their level of wisdom on their perceptions and approaches to the conflict may constitute a good indicator of how the events may unfold. Furthermore, this approach suggests the significance of facilitating and promoting wisdom among individuals in societies. This multidisciplinary study empirically investigates the relationships between the wisdom levels of stakeholders and their approach to the Cyprus conflict to shed light on future developments and raise new hopes for possible progress toward peace and the reunification of the island. It also aims to demonstrate how a psychological construct that is scrutinized at the individual level can be reflected in the preferences of individuals at the societal level, thereby establishing a sound and solid base for peace.

2. Wisdom

The concept of wisdom has deep religious and philosophical roots and is mentioned in almost every culture. Despite the multitudes of different descriptions and emphases on specific explanations, the similarities, implicit explanations, and interpretations of this concept are surprisingly convergent [

5]. From Plato to Aristotle, from Buddhism and Confucianism to Judaism, Christianity and Islam, wisdom is related to a deeper understanding of life and to the ability to make better judgments and act accordingly. It is consistently associated with sound judgment based on high cognitive capacity, extensive knowledge, deep reflection, compassion, emotional resilience, and experience [

6].

Academic circles have assumed a mantle of persistent indifference toward wisdom, exiling it to the fringe of the domain of acceptable academic research [

7]. Indeed, it is not an easy task to define the concept of wisdom, because it is complex, versatile, interpretive, and thus subjective [

8]. Therefore, to find a way for showing that wisdom has a definite meaning and making it possible to bring it within the reach of scientific methods of inquiry and investigation [

9] poses a serious challenge for the researchers. Since the 1970s, there have been signs of a steady increase in serious scientific interest in wisdom [

8]. Led by psychologists’ intent on ‘

demystifying and operationalizing the concept’ [

7], prominent researchers, such as Baltes [

10], Baltes and Freund [

11] and Baltes and Smith [

12], Sternberg [

13,

14,

15], and Ardelt [

16,

17], pioneered remarkable studies.

Despite all these valuable academic inquiries to conceptualize wisdom, Maxwell [

18] argues that it might be a better idea to focus on what this “radix” term comprises, how it produces results, and how it can be acquired, rather than how neatly it can be defined. That is the reason why researchers who try to demystify wisdom and “operationalize” it [

7] commonly focus on the components (attributes, pillars, facets, etc.) which serve as “

meta-theoretical basis” [

19], or as an “

a priory construct” [

20].

Among others, some frequently emphasized ones consist of “extensive knowledge”, “experience”, “humility”, “emotional stability”, and “feeling comfortable with ambiguity”.

Typically, a wise individual demonstrates deep curiosity and a relentless pursuit of knowledge. This quest is a kind of “nature” for the wise. They try to collect knowledge, information, and experiences, valuing them highly, then digest them, try to learn from them, and build upon them. They know that every piece of knowledge and information, however trivial it might seem, quite often makes it possible to see into the depth of things and has the potential to change the whole perspective. In fact, no good decision may emerge out of a knowledge vacuum without having the relevant information [

21]. However, one does not need to collect all the knowledge in the world to be wise and make good judgments. “

Wise man will seek to acquire the best possible knowledge about the events, but always without becoming dependent upon this knowledge” [

22], and resist to become an “information junkie” [

17,

23]. This is the pitfall which might drown one within the knowledge deluge and cause them to lose sight of decisive factors [

22]. Although knowledge of the matter is vital for judgment, it need not be the expert but narrow domain of intellectual knowledge, which is usually shallow, technocratic, functionalist, and utilitarian [

24]. Instead, one needs another kind of knowledge about “the fundamental pragmatics of life” [

8], which is deeper, profoundly personal, rich, factual, declarative, and based on a tendency to doubt existing beliefs and values.

Emotional stability or emotional management ability is frequently mentioned in wisdom literature. There is a concrete recognition of the effects of emotions in perceiving, judging, and decision-making in communities and organizational settings [

25], which not only influence thoughts, beliefs, actions, and social relations, but are an integral part of them [

26]. The wise has the capacity to keep calm and serene in the face of misadventures and sorrow, while using feelings to learn from these experiences [

27]. Thus, rather than preventing or suppressing negative emotions, wise men, through self-awareness and self-examination, have the capacity to acknowledge and accept them, with informed yet detached concern, modulating their influence and consequences [

28]. Cohen [

29] calls this “

the vulcanization of the human brain” which leads one “

to understand better the conditions under which particular emotions are engaged and interact productively with higher-level cognitive processes”. These qualities starkly manifest wisdom as a solid base for sound judgment.

3. Wisdom Is Sound and Serene Judgement

Inferences and interpretations are only possible with social praxis. Some values function as an adhesive to bind individuals to societies, thus being of an unquestionable importance. Yet, the wise know that those values are subject to discernment and interpretation, and there is no simple and concrete truth in life, like a grand narrative that explains everything [

30]. Withal, volatility, instability, and a propaganda-rich environment are the idiosyncratic standards of the current societal landscape, and this is especially true for the Cyprus conflict. This makes objective evaluation, sound decision-making, and effective execution of proper actions extremely difficult [

31]. In this context, interactions with the social world become the determining factor for more effective ways of perceiving and understanding the world [

32]. Judgments are subject to perception and interpretation, and things may be perceived differently and might carry multiple meanings [

33].

Harmonization with the norms of the community and consensus with group norms create considerable safety and security for individuals. People can be rewarded for having correct beliefs and correct attitudes. This makes it very difficult to question assumptions, criticize them, and inquire about their results. Critical thinking, a willingness to ask questions, reflection, the acceptance and embrace of uncertainty, and the courage to challenge people require a strong and internalized basis of mature thought and judgmental capacity.

It is extremely difficult to infer meaning from an environment from multiple, often contradictory, commonly chaotic signals and stimuli [

34]. Many current problems are complex and have multiple intricacies. Problems can often be approached from many standpoints. It is therefore necessary to use skill in ‘judging’ the issue at hand in context. Priem [

35] defines judgment as “

an individual understanding of relationships among objects”. Judgment includes the ability to combine difficult, questionable, and usually contradictory data to arrive at a conclusion that events prove to be correct [

36]. Decision-making in these circumstances must rely on judgment, which is inherently subjective [

37]. It should necessarily be based on a person’s worldview, which includes ‘

wishful thinking’ [

38] and focuses not only on ‘what is’ but also on ‘what should be’. It is thus an interpretation of how society will and should change. Wisdom, as the capability of judgment, refers to wise people’s ‘

ability to grasp and reconcile the paradoxes, changes, and contradictions of human nature’ [

39]. Studies of wisdom accentuate the ability to make good judgments [

7], perceptive judgments [

40], and superior judgments (e.g., [

10,

15,

16,

41]) in the face of imperfect knowledge [

7]. Even the dictionary definitions of wisdom present sound judgment as its essential trait and foremost quality (e.g., [

42]).

Wise individuals can be independent in terms of using their ideas and effective free will against the social environment, even if that environment imposes extreme pressures on them. For this reason, the wise person is not a passive figure but an engaging actor who intervenes and recreates this intense, complex, and dynamic process by actively inquiring into and scrutinizing it.

‘To live is to act and to act is to decide’, says Paul and Elder [

43]. The ‘vita activa’ [

44] necessitates perpetual decision-making. However, the quality of the decisions made by individuals in the context of extremely powerful societal dispositions and biases profoundly affects their life as well as many other people’s lives. This reality has drawn considerable attention from both academics and practitioners. Examples of decision-making models are numerous. The growing possibility of gathering vast quantities of data from the Internet and the immense processing power of computers contribute to these models, which demonstrate remarkable power if society is to remain within the existing paradigm.

However, remaining in the same paradigm in today’s turbulent environment, which is defined by rapid and profound changes, inevitably leads to dilemmas, problems, and crises.

‘Successfully dealing with these crises requires a paradigm shift, a shift which requires leaving an already accepted conceptualization of reality and being ready to accept completely new and different value frameworks [

45].

This is where the notion and the role of judgment differ from other mental faculties that do not aim to seek the truth but rather to find a subjective meaning that is generally limited by particular social and historical contexts that may not be valid for everyone in every place [

46]. The difficulty of resisting egocentrism, socio-centrism, and innate self-validation makes human ‘objectivity’ an ideal that no one perfectly achieves. It requires a great deal of intellectual humility, admitting subjectivity, and actively seeking other perspectives and competing sources of information [

43], as well as the ability to resist appeals to one’s dearest prejudices [

43,

47]. Fostering the development of sound judgment and helping individuals to develop the habit of making decisions based on reason, evidence, logic, and good sense yield the concept of wisdom.

4. Wisdom and Social Change

It seems reasonable to expect wise organizations and even wise societies that consist of wise individuals. The possibility of developing wise societies that consist of wise individuals who have the habit of resisting segregation and discrimination, are ready to accept differences, and demonstrate deep commitment to democracy might be more imaginable than assumed. Indeed, wise individuals achieve a high level of success in bringing their thoughts, emotions, and actions in line with reality, and are thus able to form open relationships with so-called ‘others’ without mutual self-deception, hidden agendas, or bad faith discontent. They can ‘

plan without being possessed by their plans, believe without being trapped in those beliefs’ and, in this way, they can detect bias and propaganda in the news media by diligently pursuing a skeptical attitude [

43].

However, this relationship may not be linear. The number of wise individuals in a society may not proportionally reflect the decisions made by the same societies. There may be dynamics involved such as those mentioned in Gladwell’s [

48] Tipping Point’: until the number of individuals reaches a certain amount, the dominant theme continues to be a socio-centric approach that relies on standard meanings underlying habitual responses [

49].

Indeed, societal learning is ‘

multilevel and involves the integration of individual, group, and organizational levels of learning’ [

50,

51,

52]. Thus, although it is individuals who learn, their knowledge should be shared and reconstructed in comprehensive interaction with the group(s) through dialectical and dialogical processes. Only through this interactive process [

53] can knowledge and understanding at the individual level be institutionalized as societal learning. Societal learning can contribute to the development of ‘wise societies’ that involve the opportunity to share information, insight, and advice [

54], discuss ideas, perspectives, common problems, needs and concerns, and probe and scrutinize alternatives with a bidirectional influence.

Rowley [

55] argues that organizational wisdom involves both the collection, transference, and integration of individuals’ wisdom and the use of institutional and social processes (e.g., structure, culture, routines) for storage. She thus claims that societies develop wisdom by promoting the expansion, dissemination, and transfer of wisdom, or wisdom creep, and cultivate a ‘wise’ culture with the aim of ‘

influencing and directing… the processes that optimize the society’s capacity for wisdom’. The ability to challenge different perceptions and interpretations, which may lead to different decisions and behaviors [

31,

56,

57], necessitates an intention to attend conjointly to personal and collective well-being together with ‘others’ [

58] This is the hallmark of wisdom.

5. Research Gap

The field of peacebuilding has traditionally been dominated by macro-level analyses that prioritize political agreements, institutional reforms, and the role of leadership in conflict resolution [

59,

60]. These approaches, while crucial, often treat peace as the absence of violence or conflict, rather than as a dynamic, sustainable process embedded in the everyday lives, values, and interactions of individuals. As a result, psychological and individual-level dimensions of peace—such as the capacity for empathy, tolerance, moral reasoning, and particularly wisdom—have received relatively limited scholarly attention in empirical peace research.

A growing body of interdisciplinary literature has begun to recognize the importance of intrapersonal and interpersonal factors in shaping attitudes toward peace, reconciliation, and coexistence [

61,

62]. However, within this emerging paradigm, the concept of wisdom remains underexplored. Despite its relevance, empirical studies investigating the direct impact of wisdom on peace-related attitudes and behaviors are notably scarce. Moreover, existing research tends to compartmentalize peacebuilding and sustainability efforts, with few integrative frameworks that link individual psychological development (such as the cultivation of wisdom) to broader societal outcomes and sustainable development goals. This gap limits our understanding of how inner transformation can lead to systemic change and a more resilient peace process.

This study seeks to fill this gap by empirically examining the role of wisdom in peacebuilding, positioning it not only as a personal virtue but as a critical enabler of collective reconciliation and long-term societal stability. By doing so, it bridges the divide between psychological inquiry and peace studies, offering a novel, sustainability-oriented perspective that emphasizes the transformative power of individual inner capacities in shaping a just and lasting peace.

6. Cyprus Conflict

The island of Cyprus has consistently attracted attention due to its central and strategic location in the eastern Mediterranean. Among others, Byzantium, Arabs, Crusaders, Venetians, and Ottomans have ruled the island. The rule of the British, who took over the island from the Ottomans, ended in 1959 with the creation of the Republic of Cyprus as a common state for both Greek and Turkish communities. However, the establishment of the Republic, instead of solving problems, set the stage for a deep and painful conflict between the two dominant ethnic communities, the Turks and the Greeks. After turbulent and sometimes bloody conflicts between the communities, the current deadlock emerged due to Turkish military intervention in 1974 following an Athens-led coup against the government. Since then, for more than 40 years, the efforts of the UN and other parties to solve the Cyprus problem have been thwarted by the inability of both communities’ representatives to reach a viable agreement [

63,

64].

It seems as if the current status quo has been internalized by both communities, indicating a determined strategy aimed at unilateral victory rather than compromise and rigid positions that view all historical and current issues in terms of ‘our truth’ and ‘their propaganda’, thereby eliminating any trust or intention to live together with the ‘other’ side [

65]. This type of framing is deeply embedded in the people’s psyche and perpetuates the status quo by highlighting mutually exclusive positions, maintaining incompatible and unbridgeable views and fixing intransient positions. A sense of frustration, betrayal, and hurt is visible in the use of language in which nearly every phrase or term used to describe the situation, or even one or the other side of the community, is politically loaded, and fuels the current stalemate [

66].

The reluctance to reach an agreement has become a ‘modus operandi’ reflected in deeply adversarial approaches of the political leaders of the two communities. It is unlikely that political and other elites will offer courageous bids that could produce a breakthrough because such actions inevitably require sacrifices linked to high political costs. The highly antagonistic approach of the leaders is supported by the conditional demands of the people for a settlement, as long as it is fair and feasible, without considering the conceptualization of justice and the viability of a settlement in each community in generally opposite ways. For community leaders, this is often necessary to show that they are continuing their ‘national cause’ commitments. Any direction outside this powerful and hostile framework brings significant costs to those who dare to disrupt it.

The ‘Set of Ideas’ that the Greek leader Vassiliou reluctantly supported in UN negotiations caused him to lose power in the subsequent presidential elections. Glafkos Clerides won the election and became Vassiliou’s successor by vigorously accusing the same ‘Set of Ideas’ approach of being insensitive to the Greek Cypriot case [

64].

A similarly revealing example is the speech made by President Papadopoulos before the 2004 Annan Plan referendum. Prior to the referendum, he defended the ‘no’ policy, declaring that he had ‘taken a state and [would] not deliver a community’. In this declaration, Papadopoulos made it clear that even the status quo may be much more preferable than alternative proposals [

65]. This phenomenon is common everywhere. Professor Mankiw [

67] of Harvard University calls elected leaders “elected followers” in the National Geographic’s documentary titled ‘Before the Flood, 2016’. He says, ‘

Presidents do what people want them to do … if we need to change the political view of the president, we need to change the public view’. He gives the example of President Obama’s stance on ‘gay marriage’, noting that Obama declared that he did not support gay marriage in 2008, when support for gay marriage was considerably low. However, in 2010, when gay marriage approval rates become far higher than negative approaches, Obama declared that same-sex couples should be able to marry.

Adherence to an impartial and passive attitude can be as expensive as opposing perceived and well-established perceptions and interpretations. Leaders can be branded ‘soft’, ‘indifferent’, or even ‘traitorous’ [

65]. As a result, political elites and the media struggle to maintain the status quo rather than defending these risks by advocating alternative solutions and thus contributing to the recreation and sustaining of existing conflicts. For this reason, a firm attitude toward the ‘enemy threats’ becomes necessary for the political survival of leaders, even though these threats no longer exist in reality.

Without mutual insecurity and fear [

68], a lasting and fair peace and the desire for coexistence can only be considered if the important parts of the population actively challenge and criticize the status quo against existing discourses. Apparently, it is more difficult to walk the talk. Deep beliefs, internalized from the past, about the so-called ‘threats from the other side’ create significant social pressures that are sustained by the social environment, close friends, and family members. These pressures extend to estrangement and exclusion, as in the case of high school students who dare to organize bi-community activities [

65]. The social environment does not allow for meaningful and effective change efforts in the foreseeable future.

It is worth noting that there are individuals who have managed to challenge existing discourses. However, they remain the minority, and they have not yet managed to influence the wider public. The focus of this research is to understand whether these individuals possess higher levels of wisdom that make them more mature, more understanding of the other, and sufficiently courageous to stand tall against nationalistic, racist, alienating social pressures.

There are various issues dividing Greek Cypriots from Turkish Cypriots. But overall, a framework of a bi-communal, bi-zonal Cypriot federation with one nationality and one sovereignty seems to be widely accepted by members of both communities [

67]. Yet a considerable number of people continue to defend the separation and annexation of territories by the so-called ‘mainland’ of Greece or Turkey.

The proposed “solutions” for the island can be categorized into five hierarchical options (see

Table 1), ranging from complete reconciliation and merger at one end to total separation at the other. These preferred “solutions” are being critically examined from both IDEAL and EVENTUAL (Realistic) perspectives.

7. The Present Study

Although different definitions and corresponding measurement tools are available, in this study, Ardelt’s [

69] three-dimensional wisdom scale (3D-WS) questionnaire was administered. It was based on the pioneering works of Clayton and Birren [

6], revealing that a concurrent interplay of cognitive, reflective, and affective personality attributes is necessary for a person to be considered “wise” [

6]. These attributes are not independent of each other, but they are not conceptually identical either.

Ardelt’s abbreviated 3D-WS scale [

70] consists of twelve items, four for each component: four items for the cognitive component, four for the reflective component, and four items for the affective component of wisdom. Instead of measuring wisdom directly, the 3D-WS assesses the cognitive, reflective, and affective dimensions of the latent variable wisdom. Questions that aim to measure the cognitive component weigh the

‘…knowledge of the paradoxical (i.e., positive and negative) aspects of human nature, tolerance of ambiguity and uncertainty, and the ability to make important decisions despite life’s unpredictability and uncertainties’.

Likewise, questions that aim to measure the reflective component weigh

‘…the ability to look at phenomena and events from different perspectives and to avoid subjectivity and projections, like; to avoid blaming other people or circumstances for one’s own situation or feelings’.

Finally, questions that aim to measure the affective element weigh

‘…the presence of positive emotions and behavior toward other beings, such as feelings and acts of sympathy and compassion, and the absence of indifferent or negative emotions and behaviors toward others’.

Thus, a person who scores high on the 3D-WS is expected to demonstrate deep sympathy and compassion toward ‘others’ (i.e., the Greeks on the island). By the effective application of self-reflection, these individuals will simultaneously increase understanding of the issues and conflicts through insight into their own and others’ motives and behaviors. This process reveals the ability to evaluate alternatives and makes it possible to embrace peace and openness to ‘others’.

All items were assessed using one of two five-point scales ranging from five (strongly agree) to one (strongly disagree) or from five (definitely true of myself) to one (not true of myself).

Ardelt’s [

28] research demonstrates a proven record of validity and reliability for the 3D-WS. She found satisfactory content and convergent validity, as well as high construct, predictive, and discriminant validity, along with internal and test-retest reliability. She also satisfactorily demonstrated that scoring high on the 3D-WS indicates the existence of three personal qualities (cognitive, reflective, and affective personal characteristics) that are ‘

necessary but also sufficient for a person to be called wise’.

Based on the 3D-WS ratings and a cross-comparison of evaluations of approaches to peace, we examine (a) whether wisdom levels are an indication of an idealized solution for the island of Cyprus, and (b) based on the assumption that the wise have a more realistic understanding of the situation and a more pragmatic and action-oriented approach to the conflict, whether there is a relationship between the wisdom scale and respondents’ realistic assessments.

This study tests the hypothesis that wise people, by overcoming the effects of nationalistic and racist pressures, will be more ready to embrace the ‘other’ (who may be portrayed as rivals or enemies by their own society, relatives, and friends) by comparing the average scores on the 3D-WS of 115 high school teachers located on the Turkish side of the island of Cyprus.

The propensity of the respondents towards the possible solutions is investigated in two steps.

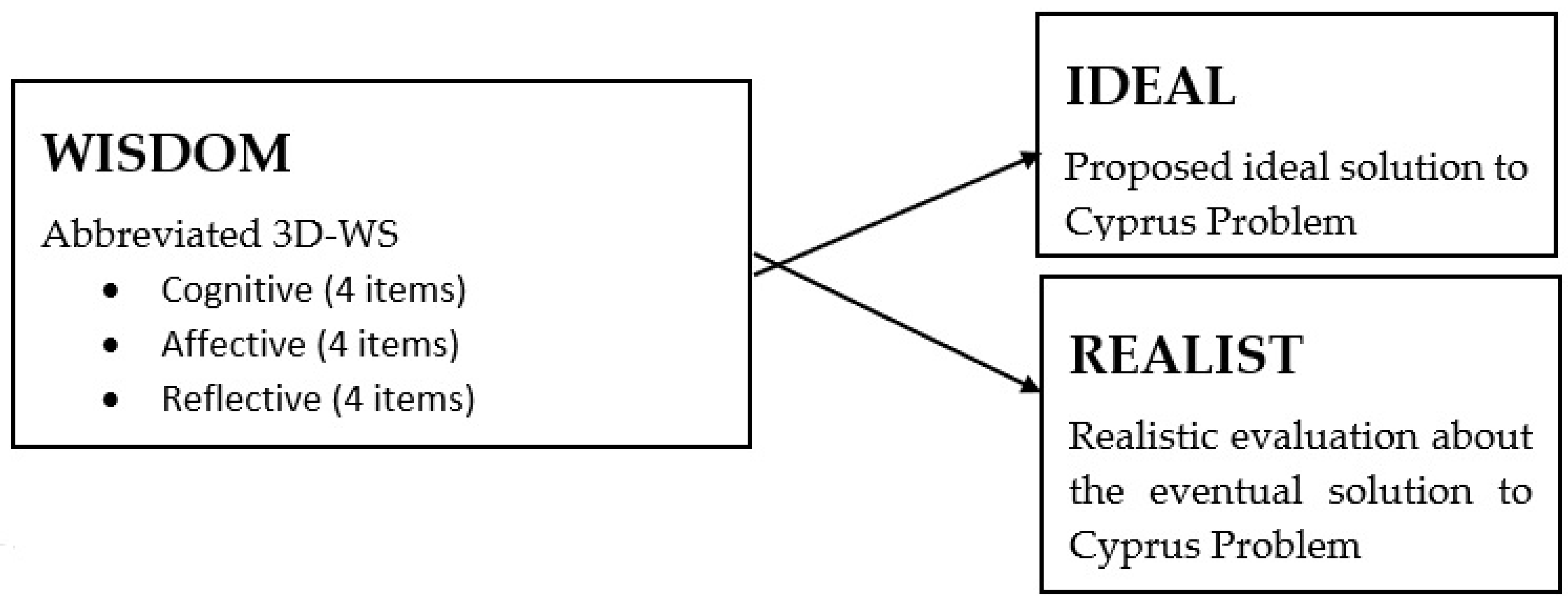

In the first step, they are asked to evaluate for the IDEAL case as the main inquiry, while EVENTUAL case explores a more REALISTIC evaluation for expected future outcomes of the respondents. Thus proposed research model is presented in

Figure 1.

Hypothesis:

Wisdom levels have a positive effect on selecting the ideal solution for conflict.

The cognitive component of wisdom has a positive effect on selecting the ideal for conflict.

The affective component of wisdom has a positive effect on selecting the ideal for conflict.

The reflective component of wisdom has a positive effect on selecting the ideal for conflict.

Wisdom levels have a positive effect on selecting the realistic evaluation solution for conflict.

- 4.

The cognitive component of wisdom has a positive effect on selecting the realistic evaluation for conflict.

- 5.

The affective component of wisdom has a positive effect on selecting the realistic evaluation for conflict.

- 6.

The reflective component of wisdom has a positive effect on selecting the realistic evaluation for conflict.

The selection of a completely random sample was necessary to capture the full range of residents currently living in North Cyprus. The use of a random number generator would have ensured the required level of randomness. However, this approach proved unfeasible. Consequently, a convenience sampling method was adopted. And thus, the study was conducted through the distribution of questionnaires to high school teachers. Although this sample does not objectively represent the broader population of North Cyprus, it provides a reasonably accurate approximation and enables the generation of highly reliable conclusions.

A pre-calculated sample size analysis (G*Power 3.1.9.7) for three predictors in total, effect size set to 0.15, error probability 0.05, and power (1-β err prob) set to 0.80, turned out to be minimum 395.

Also, sample size calculations revealed a minimum of 385 responses (95% confidence interval and 5% margin of error).

The number of usable questionnaires collected is 453, which is safely above this threshold number.

8. Results

8.1. Descriptives

The sample is predominantly female (290 female vs. 163 male). (See

Appendix A Table A1,

Table A2,

Table A3 and

Table A4 for Gender distribution, Place of Birth Distribution, and mean and median values for data.)

8.2. Research Analysis by SmartPLS, Version 4.1.0.8

The data analysis for this study utilized Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) through SmartPLS, version 4.1.0.8 software to examine a hypothesized model with multiple constructs and relationships [

71]. The analysis included calculating path coefficients, R

2 values, and effect sizes (f

2) to evaluate the strength and significance of the relationships among the variables. Bootstrapping with 5000 subsamples was performed to derive

t-values, enhancing the robustness of the path coefficients. Additionally, the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) was assessed to identify potential multicollinearity. Furthermore, convergent and discriminant validity were assessed through factor loadings, Cronbach’s Alpha, composite reliability (CR), and average variance extracted (AVE) scores, confirming the reliability and validity of the constructs in the model. (See

Appendix B Table A5,

Table A6,

Table A7 and

Table A8 for Model verifications.)

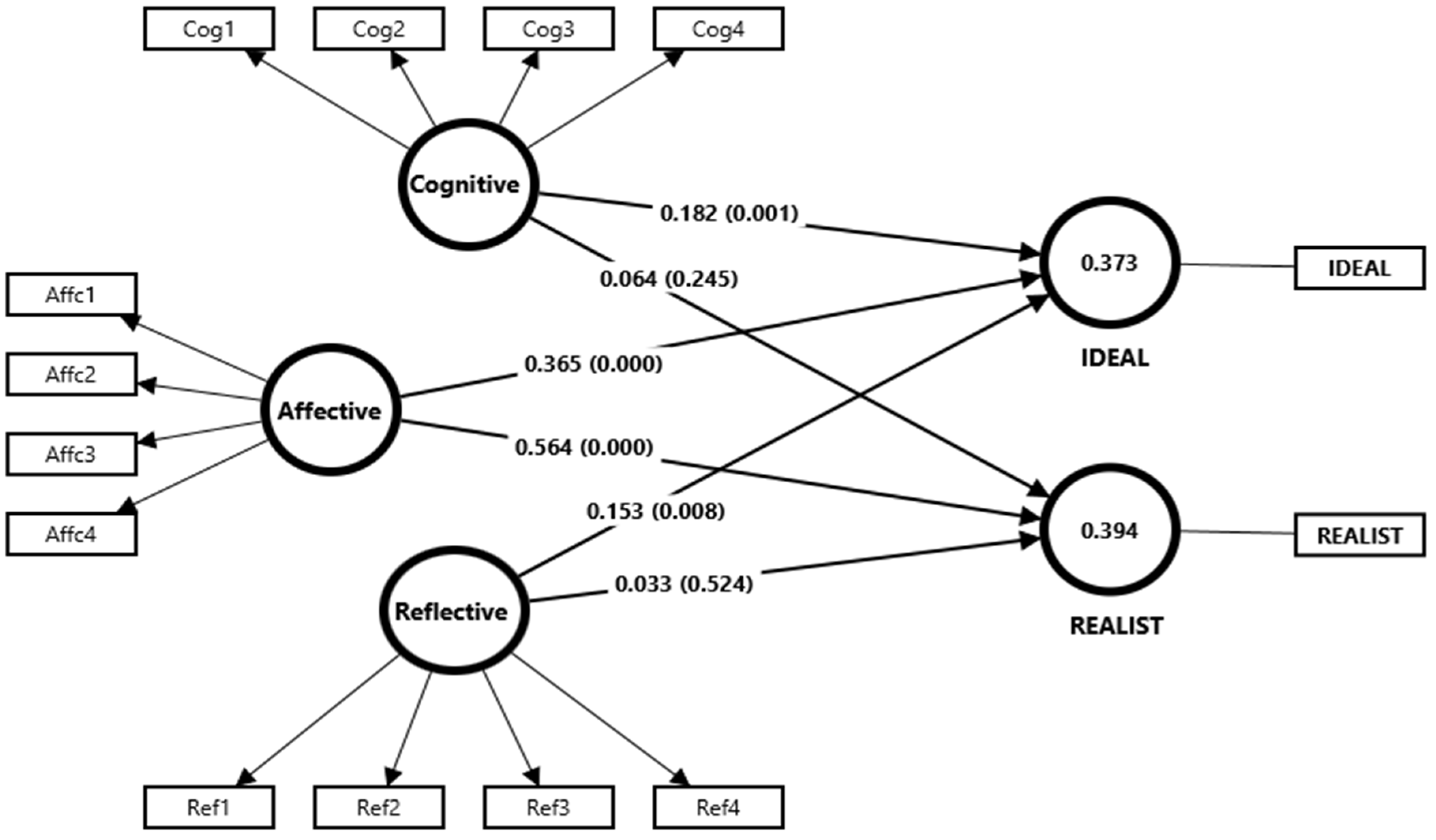

The research model created by Smart PLS software is presented as

Figure 2.

Findings as presented on

Table 2 indicate a significant impact of all cognitive, affective, and reflective components of wisdom towards peace and reconciliation. But the effect diminishes, and cognitive and reflective components becomes statistically not significant, when the same respondents are asked to choose for an eventual prediction based on more realistic evaluation. Affective component stays significant, which is theoretically sound, because this component stays the same for both ideal and eventual evaluations.

9. Discussions

This study demonstrates that the wisdom level of the respondents is a strong predictor to choose and endorse a kind of unification in Cyprus in the case of IDEAL solution. In this way, these results confirm the claim that wise people are more peace oriented, have overcome the effects of nationalistic and racist pressures, and are more ready to embrace the “other”, who may be portrayed as rivals or enemies by their own society, relatives, and friends. The higher the level of WISDOM, the more the respondents are approaching reconciliation and unification.

Things are more complicated when exploring REALIST/EVENTUAL solutions. Wisdom ceases to be a predictor for any kind of solution. This finding has profound implications. When the hope for a possible peace and re-unification process does not exist, individual differences originating from perceptions and judgments disappear, and any exertion for possible progress towards reconciliation is eradicated. The pessimistic, negative foresight of the wise is overlapping with the wishes of the non-wise, making the overall difference statistically insignificant. This result should be considered during any peace process for those who are overly cautious not to funnel early hopes to stakeholders. On the contrary, a realistic, believable hope for possible peace should be kept alive at all times.

10. Conclusions

The enduring division of Cyprus persists as a microcosm of societal, political, and economic complexities, characterized by uncertainty and a pervasive climate of mistrust, accompanied by a sense of apprehension about disruptive change. The ongoing disparities in perception and the internalized rivalries between the two communities on the island reflect a profound disintegration, compounded by a widespread apathy toward the potential for integration. At the core of these challenges lies an unreflective orientation among individuals, shaped by deeply reductive understandings and entrenched nationalistic ideologies. In this context, the cultivation of wisdom emerges as a critical path to fostering awareness of the common good, providing a framework for addressing the pragmatic concerns of daily life, and offering the potential to break the current impasse.

Wisdom, when conceptualized as a psychological construct subject to empirical inquiry, possesses a unique integrative and transformative potential [

72] that can positively influence organizations, groups, and individuals alike. By transcending the limitations of traditional and reductionist modes of thought, wisdom facilitates the development of a more open, cooperative, and collaborative societal structure. The promotion of wisdom, particularly within the context of conflict resolution, holds significant promise for achieving sustainable peace, not only in Cyprus but also in broader geopolitical contexts. Indeed, the likelihood of a comprehensive and enduring peace process is inextricably linked to the levels of wisdom exhibited by individuals within society.

Thus, it is imperative to promote the elicitation and cultivation of wisdom across educational, societal, and political spheres. The increasing integration of critical thinking courses into university curricula represents a progressive step in this direction. Furthermore, scholars such as Professor Robert Sternberg of Stanford University [

73] have pioneered initiatives aimed at teaching wisdom to younger generations, including a curriculum designed for elementary-level students. These efforts underscore the growing recognition of the value of wisdom [

74] as a tool for addressing complex global challenges. It is now critical to advance a scholarly investigation into the nature of wisdom, facilitating the development of reflection, insight, intuition, and sound judgment [

31] in individuals. Such cognitive and emotional capacities are essential for overcoming the biases inherent in conventional interpretations and for fostering a willingness to entertain alternative perspectives, particularly in the face of opposition [

75]. By promoting wisdom, societies may transition from conflict and antagonism to reconciliation and cooperation, as wise decision-making prioritizes unity over division [

31]. This process is essential for laying a solid and sustainable foundation for peace, one that is not solely determined by political leaders but rooted in the collective wisdom of the people. After all, the ultimate success of any peace initiative rests not on elite negotiations, but on the capacity of the populace to endorse and sustain a vision of peace that is built on wisdom, mutual understanding, and long-term cooperation.

11. Contributions of the Study

This study makes several important contributions to the fields of peacebuilding, psychology, and sustainable development. First, it introduces wisdom as a critical psychological construct within the peacebuilding discourse, offering an empirically grounded framework for understanding how individual inner capacities can influence broader societal outcomes. By integrating perspectives from psychology and conflict studies, the research advances a multidisciplinary approach that bridges micro-level human development with macro-level peace processes. Second, the study contributes to theory by demonstrating how wisdom—through its cognitive, reflective, and affective dimensions—can foster attitudes supportive of reconciliation, nonviolence, and social cohesion, thereby positioning it as a driver of sustainable peace. Practically, the findings suggest new avenues for peace education, community-based interventions, and policy design that center on cultivating wisdom and related values as a foundation for enduring peace. Lastly, by aligning its implications with the UN Sustainable Development Goals [

76], particularly SDG 16 (Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions), the study offers a holistic model for sustainability-oriented peacebuilding rooted in human psychology, resilience, and ethical development.

12. Limitations and Future Directions

This study has a number of limitations that may confuse the readers. First, the findings are based on a relatively small and specialized sample size. Future research should aim for larger sample sizes and for the inclusion of a broader range of randomized respondents. Similarly, the same research should be repeated on the Greek side of the Island. A comparative analysis of research conducted on both sides of the island, considering the underlying mechanisms, categories, and assumptions through which the cultural differences and contextual orientations of both ethnicities perceive the ‘other alien ethnicity’, would reveal many interesting findings. Also, the sample selection has limitations, as mentioned in the text.

Second, single and direct causality between wisdom and peace would be an oversimplification against the complex nature of life, societal relationships, conflicts, and peace processes. The relation between wisdom and attitude towards peace is complicated and may be subject to numerous intervening and moderating variables. Underestimating the effects of other influences like culture, context, and historical background has the potential to drag the researchers to grave errors.

Third, this study used a self-report measure of personal wisdom based on three latent variables which may be problematic due to social desirability and biased self-perceptions [

77]. It is great to have a psychometrically sound, easily administered instrument to measure the wisdom levels of respondents, which facilitates research in this important area. However, there are other approaches to wisdom as a psychological construct, and thus, there are other reliable measurement tools, like the “Self-Assessed Wisdom Scale (SAWS; [

78,

79]) and the Berlin Wisdom Paradigm [

58,

80]. In sound research, these alternative approaches and instruments might be considered and evaluated, emphasizing their differences to achieve more robust results.