1. Introduction

Family firms are vital to national economic development and the global economy. For instance, in China, family firms constitute 85.4% of the private sector economy [

1]. Family firms are firms owned by members of the same family [

2,

3]. Studies of family firms emphasize socioemotional wealth (SEW) to explain their strategic decision making, including internationalization [

4], instances of bribery [

5], R&D [

6,

7,

8], new product development [

9], governance behavior [

10], and innovation [

11,

12,

13].

In terms of studies on innovation, on the one hand, researchers have identified a positive relationship between family firms and innovation. For instance, family firms exhibit more efficient innovation processes [

14,

15] and launch a greater number of new products [

9]. On the other hand, studies have also found that family firms often hesitate when dealing with innovation issues. For example, families often exhibit shortsightedness and insufficient investment in research and development (R&D) [

8,

10]. We argue that inconsistent findings suggest that it is necessary to consider the types of innovative activities, that is, exploratory or exploitative innovations. Exploratory innovation involves departing from the existing technological trajectory and has the characteristics of novel knowledge, high risk, and a longer return period compared to that of exploitative innovation [

16]. These attributes can threaten the socioemotional wealth of family firms, which tend to favor stability and family control over risky ventures.

Anecdotal observations also show that strengthening exploratory innovation, overcoming path dependencies on familiar knowledge and problem-solving approaches [

17], and breaking through existing technological boundaries have become critical issues for the long-term development of Chinese family firms [

18,

19]. Simultaneously, the global race for exploratory innovation has intensified, making knowledge acquisition increasingly challenging. However, exploratory innovations regarding family firms have scarcely been studied. Thus, how would family firms make decisions when facing higher-risk exploratory innovative behaviors?

Moreover, environmental factors systematically shape a firm’s strategic goals and resource allocation logic, leading to heterogeneity in innovation orientations among decision makers [

20,

21]. In the current economic landscape, we have noticed a coexisting phenomenon: Although global industrial competition is intensifying, many firms continue to report overperformance in their annual disclosures. As firms sustain overperformance, are they at “super relaxation” of falling into innovation inertia and neglecting exploration? Conversely, as industrial competition intensifies, are firms at a “battle urgency” that catalyzes exploratory innovation? These dynamics raise important questions: does being in a calm environment or a tense environment alter the relationship between family firms and exploratory innovation? Therefore, we consider overperformance duration and industrial competition as environmental contingencies for fully understanding the effect of family firms on exploratory innovation, which may generate variations in such an effect.

To address these gaps, we propose two research questions: (1) How does family ownership affect exploratory innovation, and do family firms have different exploratory innovation tendencies compared with those of their non-family counterparts? (2) How do overperformance duration and industrial competition moderate the relationship between family firms and exploratory innovation? Based on the SEW theory, we developed hypotheses to delve into the exploratory innovation activities of family firms. We tested our hypotheses on a sample of 1332 Chinese A-share listed manufacturing family firms observed between 2009 and 2018. The empirical results indicate that family firms engaged in fewer exploratory innovations compared to non-family firms. Additionally, the negative relationship between family firms and exploratory innovation intensified as overperformance duration increased, and this negative relationship was mitigated under greater market competition.

Our study contributes to the theory in several ways. First, this study enriches existing research on innovative behavior in family firms, particularly in the field of exploratory innovation, by providing evidence that family firms have a negative impact on exploratory innovation. Second, we identify the contingent role of internal environmental factors (i.e., overperformance duration). As such, our study contributes to previous studies on family firms’ innovation by considering how family firms’ exploratory innovation is affected by their relaxed business conditions. Third, we elucidate the role of external environmental factors, such as industrial competition, as contingencies that influence firms’ exploratory innovation. In so doing, our study extends previous studies by examining how family firms’ exploratory innovation hinges on battle urgency in the external competitive environment.

2. Theory Development and Hypotheses

2.1. The Socioemotional Wealth Theory and Exploratory Innovation

Family firms are organizations established based on contractual and kinship relationships, with the goal of not purely pursuing economic benefits. Therefore, while pursuing economic profits and performance goals, family firms also focus on maintaining family emotions and consolidating non-economic wealth such as family control. These special types of “non-economic wealth” are summarized as SEW.

We argue that, based on SEW, in contrast to non-family firms, family firms tend to be less inclined to participate in exploratory innovation. Firstly, SEW is too important for family firms. In the process of establishing and developing family firms, family members have invested a lot of energy and capital [

22] and have established strong emotional attachment, identity recognition, and sense of belonging [

23]. This establishment process makes the interests and reputation of the family inseparable from the firm and also means that SEW invisibly becomes the most valuable form of wealth created by family members. According to the theory of SEW, maintaining SEW is the most important consideration factor for family firms when making decisions [

24,

25]. Specifically, socioemotional wealth can include family control and influence, family members’ identification with the company, close social relationships, the emotional attachment of family members, and the willingness of family firms to inherit across generations [

26]. Although these benefits are not in the form of money, they are often more important to family members than money. Therefore, family firms have a strong motivation to protect socioemotional wealth from loss.

Secondly, the revolutionary and dynamic nature of technological innovation determines that exploratory innovation is a challenging and risky firm behavior. Unlike exploitative innovation, which aims to integrate and improve existing technologies to meet current market demands, exploratory innovation focuses on breaking through existing technological limitations and integrating technologies across a wide range. Exploratory innovation has the attribute of “leading” and is a commercial transformation process that guides customers’ new needs and reshapes the market pattern. Exploratory innovation is a long and difficult process, and due to the limited experience available for reference, it often means “high risk” and “high cost” [

27] and requires family firms to invest significant financial resources, human resources, and time resources. It is tantamount to gambling with hard-earned socioemotional wealth. After all, any threat to socioemotional wealth implies that family firms are in a “loss-making state”, even though innovation is often an important tactic for firms to maintain competitiveness and a good socioemotional wealth strategy [

28].

Thirdly, under the motivation of protecting socioemotional wealth, families may actively avoid damaging socioemotional wealth, even if innovative behavior may increase economic wealth. Given that family firm members often view the firm as private property, family firms have a demand to maintain control over the company. However, exploratory innovation behaviors are unpredictable and uncontrollable [

29] and require numerous experiments and even failures before achieving success. Therefore, even if exploratory innovations are ultimately successful, the process of engaging in exploratory innovation will always heavily damage the economic interests of firms, greatly decreasing socioemotional wealth. When strategic decisions deviate from economic goals but help to maintain socioemotional goals, family firms may be willing to sacrifice potential future economic wealth [

30] and take action to avoid excessive high-risk innovation activities. In other words, they tend to minimize exploratory innovation. Therefore, we offer the following hypothesis:

H1. Compared to non-family firms, family firms are less likely to engage in exploratory innovation.

2.2. The Moderating Effects of Internal and External Environmental Characteristics

Do family firms consistently avoid exploratory innovation? Family firms are in a dynamic and changing environment. Environmental conditions affect their satisfaction with their current situation. In other words, the environmental factors of the firm are considered in this study. First, family firms’ exploratory innovation is related to their performance feedback. For example, when performance consistently exceeds the firm’s expectations, it signals to firms that there is a relaxation situation, encouraging them to continue on the original path. Second, exploratory innovation in family firms is also closely related to the competitive situation of the firm’s industry. Specifically, industry competition signals to firms that there is an urgent situation and forces them to pursue more exploratory innovation. We will elaborate on these arguments in the next two sections and present our hypotheses regarding environmental factors.

2.2.1. Internal Relaxation Environment: Overperformance Duration

According to the Behavioral Theory of the Firm, firms typically set historical performance or the performance of industry-advantageous competitors as “reference points” and evaluate and guide strategic decisions by comparing the gap between actual performance and the “reference points” [

31], especially in the field of innovation [

32,

33,

34]. Different performance feedback leads to different psychological perceptions of managers towards firm operations [

35], which further affects innovation strategy decisions.

Previous studies have pointed out that it is important not only to focus on the strength of performance feedback but also to pay attention to the sustainability of performance feedback [

36]. The duration of performance feedback can more significantly reflect the time dimension background faced by the firm. This study will use “overperformance duration” to measure internal performance feedback within a firm, defined as the length of time for which performance continues to meet a company’s expected state.

We argue that overperformance duration aggravates the negative effect of family firms on exploratory innovation. Firstly, the longer the overperformance duration, the more market recognition family firms receive for their current innovative behavior. Moreover, it is easier to deliver sustained returns. However, long-term stability can easily weaken the vigilance of firms, causing them to give up additional innovation efforts, especially when family firms seek to maintain their market position, high profits, investor recognition, and social and emotional wealth. At the same time, overperformance duration not only confirms the current growth trend of the firm but also meets the psychological demands of family firm decision makers for family identity recognition and a sense of belonging [

25], making them more inclined to believe that the firm is in a relatively “safe” state and attribute overperformance duration to their own abilities. This mentality will prompt family firms to use resources to maintain the original state of innovation, as well as to protect their social and emotional wealth through small updates to existing technology [

37].

Secondly, as overperformance duration increases, the firm also faces pressure to maintain superior performance. Consequently, the organization becomes more attentive to utilizing internal resources and capabilities. At this point, with further investment in exploitative innovation resources, the specialized innovation assets of firms will progressively rigidify. This will lead to an incremental increase in the costs associated with trial and error for exploratory innovation endeavors. Family firms, to avoid the “loss” of socioemotional wealth, have a motivation for risk aversion and are unwilling to bear the risks brought about by activities such as change [

38] and innovation [

39]. This leads to them tending to pursue fixed returns, maintain their competitive advantages in the original market, and improve on existing technological foundations. This inclination results in an increased motivation to invest in exploitative innovation [

31,

40]. Thus, the exploratory innovation achievements of family firms decrease accordingly.

Thirdly, from an internal corporate perspective, for overperformance duration, the performance of firms in the industry will also attract more attention from external capital markets, leading to higher expectations for the company’s future growth. Past successes will strengthen managers’ confidence in current strategies and structures [

41], leading to dependence on established models. When managers are satisfied with the current situation [

42] and become arrogant, they may distrust new technological opportunities or innovative resources, which can also result in family firms weakening their exploratory innovation motivation [

43]. Based on this, the following hypothesis is proposed.

H2. Overperformance duration can enhance the negative effect of family firms on exploratory innovation.

2.2.2. External Urgency Environment: Industrial Competition

Many studies have shown that firms’ innovation tendencies and strategic transformations are significantly influenced by changes in the external competitive market environment [

44]. Intensified industrial competition not only accelerates the rapid development of technology, knowledge, and business models but also introduces the unpredictability of newly entered firms [

45], which, in turn, exacerbates the risks of technological obsolescence, resource competition, and loss of market niche, threatening the survival of firms [

46]. However, it also concurrently gives rise to more technological opportunities [

47], efficient information acquisition, and opportunities for market reshuffling. These factors present both challenges and opportunities, potentially propelling firms into an “urgent battle-readiness state” [

48]. Against this backdrop, family firms face greater challenges in maintaining market share and fulfilling the demands of stakeholders. Consequently, family firms exhibit characteristics akin to those of general firms, focusing on economic benefits to appease stakeholders. To sustain a competitive edge, family firms must seek new knowledge and actively engage in exploratory innovation activities.

We argue that industrial competition alleviates the negative effect of family firms on exploratory innovation. Firstly, when a firm is immersed in a fiercely competitive market environment, its technological capabilities, existing resources, and market niche may only provide a transient advantage [

49]. In a fast-paced competitive environment, products and technologies can quickly become obsolete [

50], making survival the primary objective for firms. To avoid the loss of socioemotional wealth or to pursue remarkable achievements, family firms need to explore more competitive avenues of innovation [

51,

52].

Secondly, as industrial competition intensifies, the market gradually shifts towards a buyer-dominated structure where customer needs become paramount [

53]. Family firms must distinguish themselves by leveraging product differentiation to stand out with their unique characteristics and establish a distinctive competitive advantage [

54]. Meanwhile, intensified product homogeneity and the knowledge spillover effect compel firms to shift towards the search for new knowledge [

55]. These factors accelerate the mobility of R&D talent, necessitating that family firms increase their investment and incentives in R&D human resources [

56], which not only promotes the exploration of new knowledge but also diminishes the aversion of firms towards exploratory innovation.

Thirdly, previous research has indicated that industry competition can significantly reduce the extent of information asymmetry between managers and investors. It can make the behavior of firm managers more transparent and easier to be evaluated by third parties [

57] and regulated by stakeholders, thereby reducing instances of “management laziness”. Consequently, industry competition encourages members of family firms to actively explore new competitive advantages. In summary, we contend that external industry competition intensifies the exploratory innovation propensity of family firms. This mechanism of action can be encapsulated as “external industry competition—awareness of socioemotional wealth crisis—exploratory innovation behavior”. Based on this, we propose Hypothesis 3:

H3. Industrial competition can mitigate the negative effect of family firms on exploratory innovation.

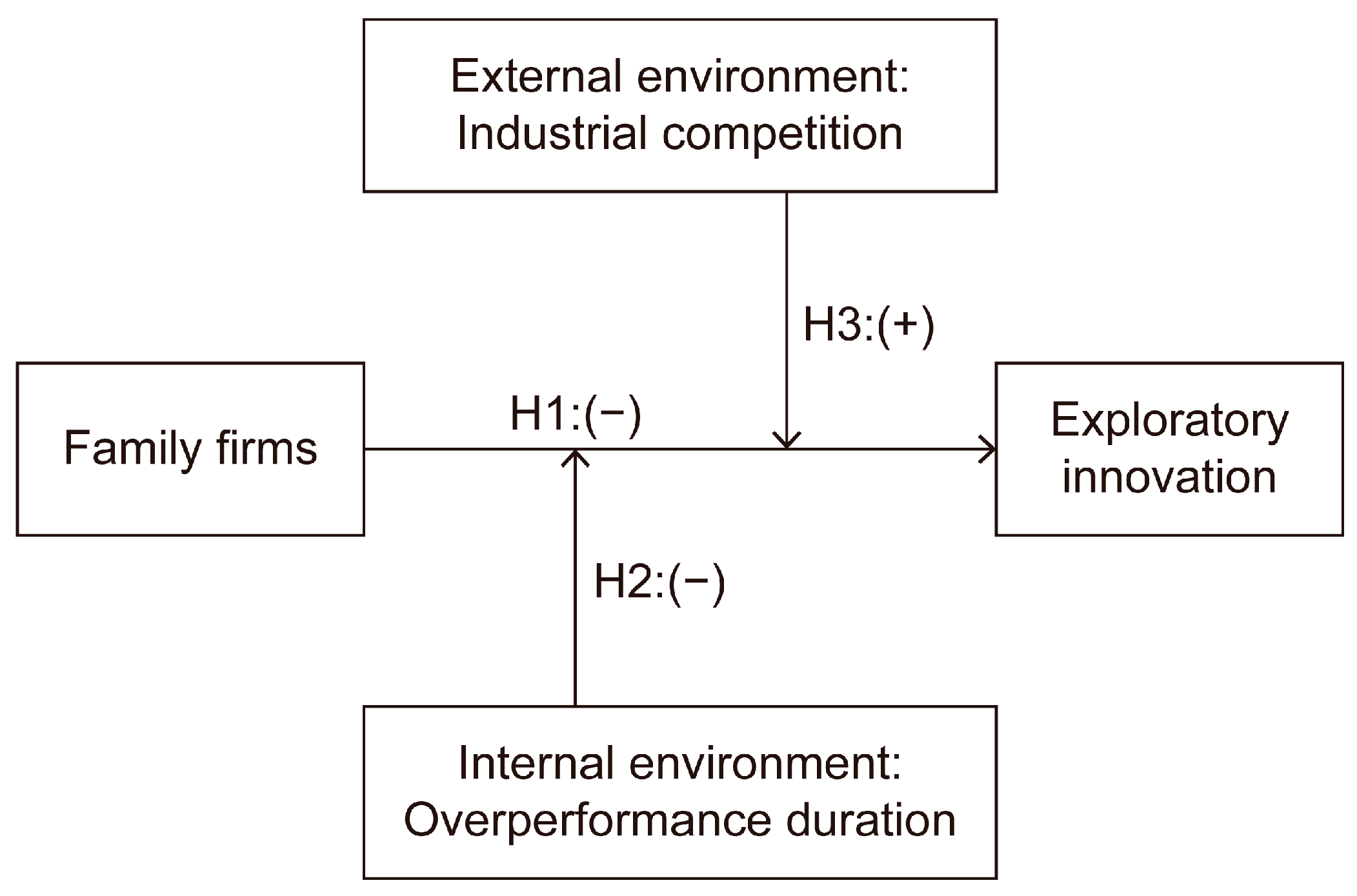

Figure 1 illustrates our research model.

3. Methods

3.1. Sample Selection and Data Sources

To test our hypotheses, we used Chinese A-share manufacturing firms listed on the Shanghai and Shenzhen Stock Exchanges from 2009 to 2018 as the research sample. The dataset came from multiple sources. We chose our sample from firms within the manufacturing sector, considering that a significant portion of exploratory innovation initiatives originate from this domain [

58]. Moreover, as a core sector of the real economy, the manufacturing industry exhibits innovation activities that are both typically representative and highly observable. We collected each firm’s basic, financial, TMT, R&D, industrial, and family member information from CSMAR databases (

https://data.csmar.com/; accessed on 29 December 2020), and the data on patents used to construct the dependent variables were obtained from the incopat databases (

http://nmaly.sharepat.com.cn; accessed on 29 December 2020). To ensure the reliability and stability of the sample, we excluded firms with abnormal operational conditions (ST or *ST firms). We also deleted observations with missing values, and we obtained 3910 observations involving 1332 listed firms over the period 2009–2018. To reduce the likelihood of reverse causality, the dependent variable, independent variables, moderating variables, and control variables were all lagged by one year (i.e., t − 1).

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Independent Variable

Family firms: To define family firms, we used the family firm database of CSMAR to determine the sample of family firms among A-share listed companies and selected a sample of manufacturing firms from it. On this basis, we employed the statistical method mentioned by Amato [

59,

60] to further refine our sample. Specifically, this method suggests that family involvement in firms (such as ownership, board of directors, and management) is a sufficient condition for gaining family influence [

60,

61]. That is, firms that meet the following conditions are defined as family firms: (1) private firms controlled by families or natural persons; (2) at least two family members hold firm shares or hold firm positions [

61]. Therefore, based on the CSMAR family firm database, we further screened and introduced dummy variables. If at least two family members were involved in managing the firm, it was defined as a family firm with a value of “1”; otherwise, it was “0”.

3.2.2. Dependent Variable

Exploratory innovation: According to the study by Duysters [

62] conducted in 2020, we employed a method of calculating concentration to measure exploratory innovation, and we measured firm exploration as a continuous variable [

62], which captured the novelty and diversity of specific patent classes in year t, based on patents applied for by the firm in the past five years. We measured exploratory innovation as follows:

We used

to denote patent concentration, where

represents the share of patent subclass r in all patents held by company i, and N is the number of different patent subclasses. This metric reflects the breadth of knowledge of the company in a particular year, with a range from 0 to 1 [

62,

63].

indicates the sum of the squares of the shares of all patent subclasses within the total patent count (such as the square of the share of class A patents plus the square of the share of class B patents, and so on up to class N). The higher this

is, the more concentrated the company’s patents have been over the past five years in only a few subclasses, indicating higher patent concentration and lower exploration. Conversely, 1 −

reflects the dispersion degree of the company’s exploratory patents. In other words, this patent concentration metric examines the distribution of all patents across different categories for a company over the previous five years, calculating the proportion of each category by dividing the number of patents in each category by the total number of patents. If the company’s patents over the past five years are primarily concentrated in a few categories, such as classes A, B, and C, this indicates less exploratory innovation; however, if 1 −

is higher, meaning greater dispersion, then the level of exploratory innovation is considered to be high.

We measured N by taking the first four digits of the patent’s International Patent Classification (IPC) code to distinguish the technical subclass to which the patent belonged. According to March’s research in 1991, a firm’s acquisition of new knowledge, rather than remaining within familiar domains, represents the firm’s exploratory innovation [

64]. In the existing literature, four-digit IPC subclass codes, which identify technological heterogeneity based on the process, structure, and function of technology, are commonly used as a measure to identify a firm’s entry into new technological fields and exploratory innovation [

65]. Therefore, we utilized new combinations of IPC subclass codes to measure the new knowledge acquired by firms. Due to the lagged response of firms in acquiring, assimilating, and adopting new knowledge reflected in patent applications, and considering the potential for reducing reverse causality, the model incorporated a one-year lag for the dependent variable.

3.2.3. Moderating Variables

Overperformance duration: Based on the studies conducted by Ye et al. in 2020 [

38] and Yu et al. in 2019 [

32], in terms of performance indicator measurement, we chose historical performance indicators (comparing against its performance in a prior period) as the basis for measurement. We believe that there are barriers to mobility between firms within an industry, originating from industry structural factors and isolation mechanisms of firms’ resources and capabilities. These isolation mechanisms help high-performance firms to maintain a competitive advantage while also preventing underperforming firms from improving performance [

66]. Therefore, superior (or inferior) performance relative to that of peers is more likely to be repeated in subsequent periods. Choosing historical performance is more significant for reference in a firm’s own strategic decision making [

67]. The historical aspiration (HA) is computed as the exponentially weighted moving average of a firm’s previous performance [

36,

68]:

where t denotes the year, and i indicates the firm.

denotes weights assigned to performance in the prior period, reflecting how quickly firms update their aspiration levels (we report our main results using

= 0.3, which yields the best model fit).

This study measures overperformance duration as follows: If performance (ROA) in year t > historical expectations, then overperformance duration is counted as 1; otherwise, it is 0. If performance (ROA) in year t + 1 continues to meet historical expectations, overperformance duration in year t + 1 is increased by 1 based on year T; otherwise, it is reset to 0. This is calculated as the gap between firm performance and historical aspiration level. Firm performance is measured based on the return on assets (ROA) of the firm.

Industrial competition: A common and effective method for measuring industry competition is to use the Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (HHI) [

69,

70]. The HHI is a comprehensive indicator for measuring industry concentration and market share. It works by measuring the sum of squares of the total sales revenue or market share of each industry competitor within an industry (which can ignore smaller competitors). The HHI can reflect the total size of the firms in the market and the condition of the industry structure. As the HHI assigns different weights according to the size of firms, it can truly reflect the differences in scale among firms, and larger firms are more sensitive to this index. Therefore, this study uses the opposite number of HHI (1-HHI) to represent the industry competition of the entire industry. The closer (1-HHI) approaches 1, the more intense the industry competition becomes.

3.2.4. Control Variables

We included the following variables in our analysis to control the impact of factors that may explain our results. First, we controlled some basic characteristics of the firm. We measured firm size (SIZE) by the logarithm of the annual average number of employees in the firm and firm age (FAGE) by the absolute value of the difference between the observation year and the establishment year. Next, we controlled some financial indicators of the firm. Total return on assets (ROA) was measured by net profit after tax/total assets, and R&D investment (RD) was measured as the proportion of R&D investment in operating revenue. Additionally, we controlled some corporate governance indicators. We measured board size (BOA) as the number of directors on the board and institutional investor shareholding ratio (INS) as the sum of the shareholding ratios of ten types of institutional investors, including securities investment funds, securities firms, qualified foreign institutional investors (QF11), social security funds, insurance companies, trust companies, finance companies, banks, non-financial listed companies, and other institutions. Finally, we controlled environmental indicators and CEO-level indicators. We measured the marketization index (MAK) based on the results from the annual data of each province and city in the “China Provincial Marketization Index Report (2021)” and CEO gender (GEN) based on the personal characteristics indicators of directors, supervisors, and senior executives in the CSMAR database, with male CEOs coded as 1 and female CEOs coded as 0.

3.3. Modeling

As the data spanned multiple years for the firms under observation, a panel data model was used. Specifically, we adopted a fixed-effects model and OLS (ordinary least squares) regression model for hypothesis testing. After the Hausman test, we chose a panel fixed-effects model for hypothesis testing.

Firstly, without considering the explanatory and moderating variables, we needed to conduct regression with exploratory innovation and control variables to explore the relationship between the two types of variables. Secondly, to test Hypothesis 1, we needed to add the dummy variable for family firms, an explanatory variable to investigate the impact of family firms on exploratory innovation. Finally, to test the moderating mechanism of the moderating variables overperformance duration (HAC) and industrial competition (IND) in Hypothesis 2 and Hypothesis 3 on the relationship between family firms and exploratory innovation, we added interaction terms for the moderating variables and family firm dummy variable, specifically (FAM × HAC) and (FAM × IND). We conducted analyses using the Tobit command in Stata 15. The model was structured as follows:

Among them, i and t represent a certain firm and a certain year, respectively. The dependent variable Exp

i,t represents the exploratory innovation level of firm i in year t. The independent variable represents the family firm status, which indicates whether a firm i is a family firm in year t.

represents overperformance duration.

represents the industrial competition.

represents the control variables listed in

Table 1.

4. Results

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics and correlation coefficients and shows that there was a significant negative correlation between family firms and exploratory innovation, which is consistent with the baseline hypothesis in this study. The variance inflation factor (VIF) analysis for each indicator showed a maximum value of 1.54, well below 10, and the values of the correlation coefficients between the core variables were all less than 0.5. It can be concluded that the impact of multicollinearity on the results was not serious and appropriate for further regression analysis.

Table 2 lists the OLS regression results in this study using stepwise models. Model 1 served as the baseline model, testing the dependent variable exploratory innovation (EXP) and the control variables. Model 2 was the regression result of the relationship between family firms and exploratory innovation. Model 3 listed the test results of the moderating effect of overperformance duration on the relationship between family firms and exploratory innovation. Model 4 listed the test results of the moderating effect of industrial competition on the relationship between family firms and exploratory innovation. Finally, Model 5 was the full model, which incorporated the interaction term between the independent variable and the two moderating variables.

Hypothesis 1 predicted a negative effect of family firms on exploratory innovation. The results in Model 2 indicated a significant negative correlation between family firms and exploratory innovation (β = −0.044, p < 0.01). Therefore, Hypothesis 1 was supported.

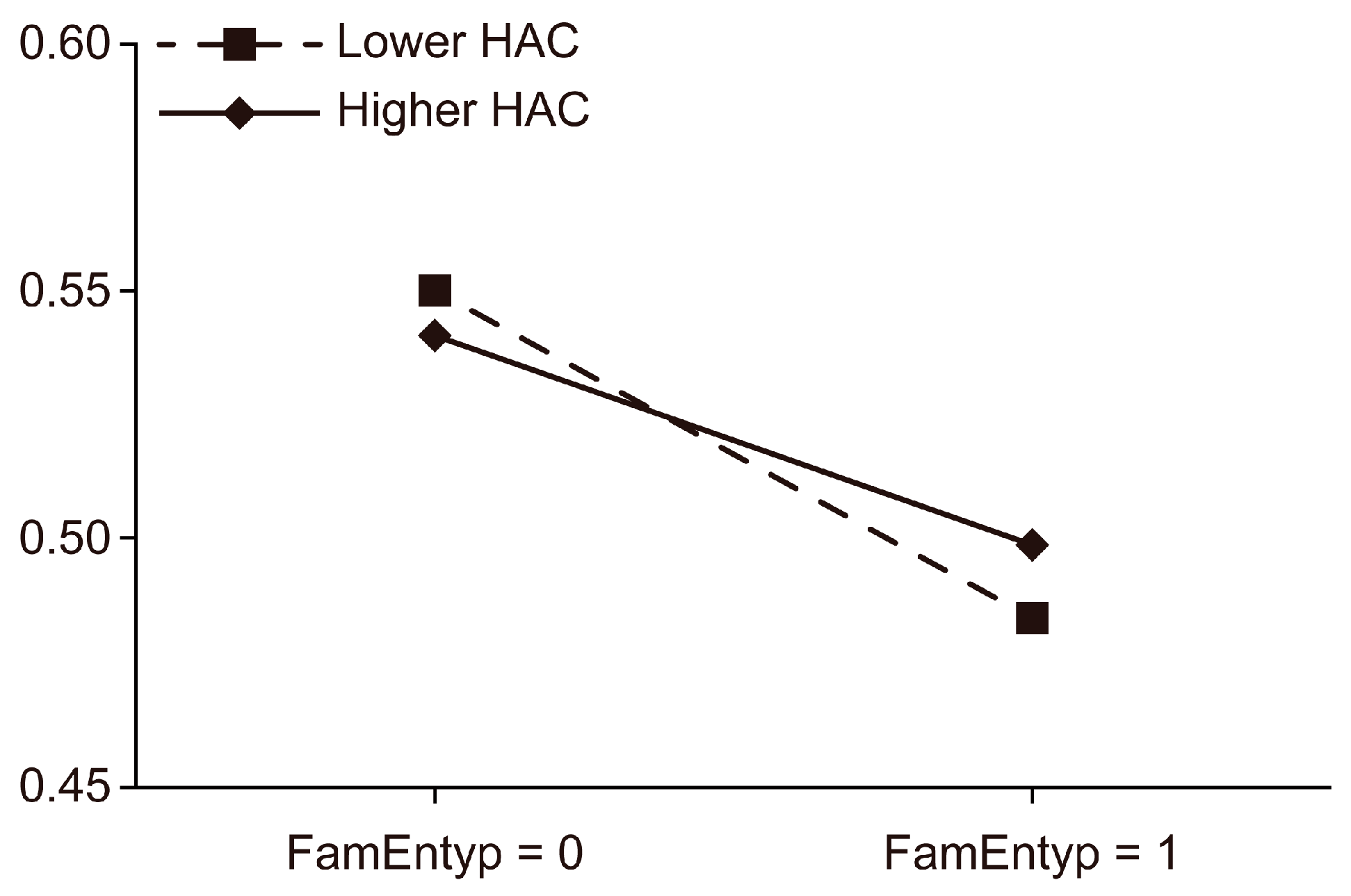

Hypothesis 2 predicted a negative moderating effect of overperformance duration on the relationship between family firms and exploratory innovation. The coefficient of interaction between family firms and overperformance duration was negative and significant in Model 3 (β = −0.005,

p < 0.1), suggesting a negative moderating impact of overperformance duration on the relationship between family firms and exploratory innovation. Therefore, Hypothesis 2 was supported. Following the methodology outlined by Aiken [

71],

Figure 2 illustrates the interaction effect. As shown in

Figure 2, when overperformance duration was high, the negative impact of family firms on exploratory innovation was stronger.

Hypothesis 3 predicted a positive moderating effect of industrial competition on the relationship between family firms and exploratory innovation. The coefficient of interaction between family firms and industrial competition was positive and significant in Model 4 (β = 0.264,

p < 0.1), suggesting a positive moderating impact of industrial competition on the negative relationship between family firms and exploratory innovation. Therefore, Hypothesis 3 was supported.

Figure 3 illustrates the interaction effect.

Robustness Test

To confirm the robustness of the findings in our study, we conducted robustness testing through two approaches. Firstly, we used an alternative measure of exploratory innovation for all models. Specifically, in constructing the regression model, we still utilized a concentration calculation method [

62] to measure exploratory innovation, but we now measured the number of different patent subclasses by taking the first three digits of the patent’s IPC code to distinguish the technical subclass. The results are shown in

Table 3. The results show that in the alternative model, the impact of family firms on exploratory innovation was negative and significant, supporting Hypothesis 1; the moderating effect of the duration of superior performance was also negative and significant, supporting Hypothesis 2; and the moderating effect of industry competition was positive and significant, supporting Hypothesis 3.

Secondly, in constructing the aforementioned regression model, this study selects the OLS (ordinary least squares) model for regression of variables. To enhance the robustness of the findings, this study used the Tobit model to re-run the analysis. The results are shown in

Table 4. The results after rerunning the analysis were still consistent with our previous findings, indicating that the choice of regression model did not adversely affect the results.

5. Conclusions and Discussion

Based on the SEW theory, we developed hypotheses to explore both the exploratory innovation activities of family firms and how environmental factors in slack and urgent contexts moderate this relationship. We tested our hypotheses using a sample of 1332 Chinese A-share listed manufacturing family firms from 2009 to 2018.

Firstly, we found that family firms were less likely to engage in exploratory innovation compared to non-family firms. This study showed that family firms had a negative impact on exploratory innovation, which contrasts with findings for the United States and Japan, where family firms’ unique resources and characteristics drive better innovation performance [

8,

14].

Secondly, we examined how the relationship between family firms and exploratory innovation changes under different slack and urgent conditions. Specifically, the negative relationship between family firms and exploratory innovation intensifies during overperformance durations but is mitigated by increased market competition.

During an overperformance period, family firms may foster complacency and inertia, tending to remain static and rely on their existing strategies [

37], which can lead to innovation path dependence and risk-averse behavior. Therefore, the duration of overperformance amplifies the negative impact on exploratory innovation. However, as industrial competition intensifies and managerial slackness is reduced, family firms face an urgent need to innovate to maintain their competitive advantage and protect their SEW. Thus, competition encourages exploratory innovation, which not only protects but also enhances SEW.

The contributions of this study cover several key areas. Firstly, our study extends SEW theory by examining its application to exploratory innovation, a relatively underexplored area in family firm research. Existing research mainly focuses on inheritance structure and management heterogeneity, there has been less focus on the differences in innovation behaviors between family and non-family firms. Moreover, the varying sample selections have led to different conclusions. This study thinks family involvement in firms is a sufficient condition for gaining family influence and categorizes firms into family and non-family firms based on data from the Shanghai and Shenzhen Stock Exchanges, measuring exploratory innovation through patent concentration. Our conclusions differ from those of prior studies based on developed economies [

14], offering valuable insights into the impact of family firms in emerging economies.

Secondly, this study explored the boundary conditions between family firms and exploratory innovation. Based on data from Chinese manufacturing family firms, this study found that overperformance duration had a negative impact on exploratory innovation, while industry competition mitigated this negative effect. This finding fills the gap in existing research regarding the coexistence of intense industry competition and sustained performance growth, which has been overlooked both domestically and internationally. It makes an important contribution to the field of performance feedback research and provides a new perspective on exploratory innovation in Chinese family firms.

Our study also offers valuable insights and practical implications for policymakers, investors, and family firms. For policymakers, providing institutional support and policy guidance can encourage family firms to increase their investment in exploratory innovation. For investors, it is important to recognize that family firms may take longer to change their avoidance attitude towards exploratory innovation. Therefore, long-term investors should comprehensively analyze a firm’s intentions and actions regarding innovation. For family business managers, it is crucial to understand that the excessive protection of SEW and a relaxed environment may hinder technological innovation, especially in industries with high innovation demands. To overcome this barrier, they should implement management measures to activate the firm’s systems, leverage the competitive industrial environment, keenly seize innovation opportunities, and guide innovation decisions from the top down.

6. Limitations and Future Research

Our study has the following limitations, which also provide opportunities for future research. First, we only discussed the impact of family firms on exploratory innovation, without considering business heterogeneity with factors such as managers’ educational background and generational differences, which may influence innovation outcomes [

72]. Future research could refine classifications and enrich theoretical frameworks.

Second, performance feedback and industry competition levels are insufficient to fully capture the internal and external environments of firms. Internal factors, such as corporate culture and entrepreneurial spirit, as well as external variables, such as economic systems and industrial policies, may also affect innovation. Future research could explore the impact of both internal and external factors on innovation from multiple perspectives.

Third, our study is limited to family firms in the manufacturing industry. However, family firms can operate across a variety of traditional industries, such as agriculture or information technology, and they can range in size from small businesses involving only a few family members to large enterprises. Future research should conduct more detailed analyses across different industries and heterogeneous types of family firms.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.Z. and C.D.; data curation, Y.Z., C.D., and F.C.; formal analysis, Y.Z.; methodology, Y.Z. and C.D.; project administration, F.T.; software, Y.Z.; supervision, F.T. and C.D.; validation, Y.Z.; writing—original draft, Y.Z.; writing—review and editing, C.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant 72072008 and the Highlevel Talent Research Initiation Project of Chongqing Technology and Business University (Grant NO. 2555001).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

We collected the firms’ basic, financial, TMT, R&D, industrial, and family member information from CSMAR databases (

https://data.csmar.com; accessed on 29 December 2020), and the data on patents used to construct the dependent variables were obtained from the incopat databases (

http://nmaly.sharepat.com.cn; accessed on 29 December 2020). To ensure the reliability and stability of the sample, we excluded firms with abnormal operational conditions (ST or *ST firms). We further deleted observations with missing values, and we obtained 3910 observations involving 1332 listed firms over the period 2009–2018. To reduce the likelihood of reverse causality, the dependent variable, independent variables, moderating variables, and control variables were all lagged by one year (i.e., t − 1).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chen, Y.B.; Li, W.; Lin, K.J. Cumulative voting: Investor protection or antitakeover? Evidence from family firms in China. Corp. Gov. Int. Rev. 2015, 23, 234–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J. Definitions and typologies of the family business. In Harvard Business School Background; Harvard Business School: Boston, MA, USA, 2001; pp. 802–807. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, J.; Tagiuri, R. The influence of life stages on father-son work relationships in family companies. Fam. Bus. Rev. 1989, 2, 47–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesinger, B.; Hughes, M.; Mensching, H.; Bouncken, R.; Fredrich, V.; Kraus, S. A socioemotional wealth perspective on how collaboration intensity, trust, and international market knowledge affect family firms’ multinationality. J. World Bus. 2016, 51, 586–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Min, Y. The ability and willingness of family firms to bribe: A socioemotional wealth perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2023, 184, 237–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, J.H. R&D investments in family and founder firms: An agency perspective. J. Bus. Vent. 2012, 27, 248–265. [Google Scholar]

- Chrisman, J.J.; Patel, P.C. Variations in R&D investments of family and nonfamily firms: Behavioral agency and myopic loss aversion perspectives. Acad. Manag. J. 2012, 55, 976–997. [Google Scholar]

- Duran, P.; Kammerlander, N.; van Essen, M.; Zellweger, T. Doing more with less: Innovation input and output in family firms. Acad. Manag. J. 2016, 59, 1224–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayyagari, M.; Demirgüç-Kunt, A.; Maksimovic, V. Firm innovation in emerging markets: The role of finance, governance, and competition. J. Financ. Quant. Anal. 2011, 46, 1545–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, H.S.; Jeong, E.; Cho, H. Toward an Understanding of Family Business Sustainability: A Network-Based Systematic Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Massis, A.; Audretsch, D.; Uhlaner, L.; Kammerlander, N. Innovation with limited resources: Management lessons from the German Mittelstand. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2018, 35, 125–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Chen, L. Dispersion of Family Ownership and Innovation Input in Family Firms. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Hughes, M. Radical innovation in family firms: A systematic analysis and research agenda. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2020, 26, 1199–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asaba, S.; Wada, T. The contact-hitting R&D strategy of family firms in the Japanese pharmaceutical industry. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2019, 32, 277–295. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, R.C.; Reeb, D.M. Founding-family ownership and firm performance: Evidence from the S&P 500. J. Financ. 2003, 58, 1301–1328. [Google Scholar]

- Katila, R.; Ahuja, G. Something old, something new: A longitudinal study of search behavior and new product introduction. Acad. Manag. J. 2002, 45, 1183–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahuja, G.; Morris Lampert, C. Entrepreneurship in the large corporation: A longitudinal study of how established firms create breakthrough inventions. Strateg. Manag. J. 2001, 22, 521–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, X.; Song, T.; Ren, L. The role of founder reign in explaining family firms’ R&D investment: Evidence from China. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2023, 26, 422–445. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Schwaag Serger, S.; Tagscherer, U.; Chang, A.Y. Beyond catch-up—Can a new innovation policy help China overcome the middle income trap? Sci. Public Policy 2017, 44, 656–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Xia, J.; Zajac, E.J. On the duality of political and economic stakeholder influence on firm innovation performance: Theory and evidence from Chinese firms. Strateg. Manag. J. 2018, 39, 193–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mnasri, K.; Ellouze, D. Ownership structure, product market competition and productivity Evidence from Tunisia. Manag. Decis. 2015, 53, 1771–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullins, F. A piece of the pie? The effects of familial control enhancements on the use of Broad-Based employee ownership programs in family firms. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2018, 57, 979–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.C.; Kotlar, J.; Memili, E.; Chrisman, J.J.; Massis, A.D. The pursuit of international opportunities in family firms: Generational differences and the role of Knowledge-Based resources. Glob. Strategy J. 2017, 8, 136–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Mejia, L.R.; Haynes, K.T.; Núñez-Nickel, M.; Jacobson, K.J.; Moyano-Fuentes, J. Socioemotional wealth and business risks in family-controlled firms: Evidence from Spanish olive oil mills. Admin. Sci. Q. 2007, 52, 106–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Mejia, L.R.; Cruz, C.; Berrone, P.; De Castro, J. The bind that ties: Socioemotional wealth preservation in family firms. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2011, 5, 653–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrone, P.; Cruz, C.; Gomez-Mejia, L.R. Socioemotional Wealth in Family Firms. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2012, 25, 258–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyres, N. Evidence on the role of firm capabilities in vertical integration decisions. Strateg. Manag. J. 1996, 17, 129–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondi, E.; De Massis, A.; Kotlar, J. Unlocking innovation potential: A typology of family business innovation postures and the critical role of the family system. J. Fam. Bus. Strategy 2019, 10, 100236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Massis, A.; Frattini, F.; Pizzurno, E.; Cassia, L. Product innovation in family versus nonfamily firms: An exploratory analysis. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2015, 53, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsao, S.M.; Chang, Y.W.; Koh, K. Founding family ownership and myopic R&D investment behavior. J. Account. Audit. Financ. 2019, 34, 361–384. [Google Scholar]

- Cyert, R.M.; March, J.G. A Behavioral Theory of the Firm; Martino Fine Books: Eastford, CT, USA, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, W.B.; Minniti, M.; Nason, R. Underperformance duration and innovative search: Evidence from the high-tech manufacturing industry. Strateg. Manag. J. 2019, 40, 836–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinkle, G.A. Organizational aspirations, reference points, and goals: Building on the past and aiming for the future. J. Manag. 2012, 38, 415–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotiloglu, S.; Chen, Y.; Lechler, T. Organizational responses to performance feedback: A meta-analytic review. Strateg. Organ. 2021, 19, 285–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.R. Determinants of firms’ backward-and forward-looking R&D search behavior. Organ. Sci. 2008, 19, 609–622. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, Y.; Yang, Y.; Yu, W.; Nason, R. Performance feedback persistence: Comparative effects of historical versus peer performance feedback on innovative search. J. Manag. 2020, 47, 1053–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, T.C.; Lovallo, D.; Caringal, C. Causal ambiguity, management perception, and firm performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2006, 31, 175–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeker, W. Strategic change: The influence of managerial characteristics and organizational growth. Acad. Manag. J. 1997, 40, 152–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greve, H.R. A behavioral theory of R&D expenditures and innovations: Evidence from shipbuilding. Acad. Manag. J. 2003, 46, 685–702. [Google Scholar]

- Danneels, E. The dynamics of product innovation and firm competences. Strateg. Manag. J. 2002, 23, 1095–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard-Barton, D. Core capabilities and core rigidities: A paradox in managing new product development. Strateg. Manag. J. 1992, 13, 111–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greve, H.R. Performance, aspirations, and risky organizational change. Admin. Sci. Q. 1998, 43, 58–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, J.; Klingebiel, R.; Wilson, A.J. Organizational structure and performance feedback: Centralization, aspirations, and termination decisions. Organ. Sci. 2016, 27, 1065–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Perlines, F.; Ibarra Cisneros, M.A. The Role of Environment in Sustainable Entrepreneurial Orientation: The Case of Family Firms. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auh, S.; Menguc, B. Balancing exploration and exploitation: The moderating role of competitive intensity. J. Bus. Res. 2005, 58, 1652–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, W.P. The dynamics of competitive intensity. Admin. Sci. Q. 1997, 42, 128–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, P.; Del Río, M.L.; Varela, J.; Bande, B. Relationships among functional units and new product performance: The moderating effect of technological turbulence. Technovation 2010, 30, 310–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q.; Gu, F.F.; Xie, E.; Wu, Z. Exploratory and exploitative OFDI from emerging markets: Impacts on firm performance. Int. Bus. Rev. 2020, 29, 101661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Nie, M. The impact of innovation and competitive intensity on positional advantage and firm performance. J. Am. Acad. Bus. 2008, 14, 205–210. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, Y.; Roundy, P.T.; Chok, J.I.; Ding, F.; Byun, G. “Who knows what?” in new venture teams: Transactive memory systems as a micro-foundation of entrepreneurial orientation. J. Manag. Stud. 2016, 53, 1320–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S.A.; Das, S.R. Innovation strategy and financial performance in manufacturing companies: An empirical analysis. Prod. Oper. Manag. 1993, 2, 15–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Ma, J.; Zhao, H.; Cater, J.; Arnold, M. Family involvement, environmental turbulence, and R&D investment: Evidence from listed Chinese SMEs. Small Bus. Econ. 2019, 53, 1017–1032. [Google Scholar]

- Prudhomme, G.; Zwolinski, P.; Brissaud, D. Integrating into the design process the needs of those involved in the product life-cycle. J. Eng. Des. 2003, 14, 333–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, A.S.; Griffith, D.A.; Cavusgil, S.T. The influence of competitive intensity and market dynamism on knowledge management capabilities of multinational corporation subsidiaries. J. Int. Mark. 2005, 13, 32–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, K.P.; Chou, C. The impact of open innovation on firm performance: The moderating effects of internal R&D and environmental turbulence. Technovation 2013, 33, 368–380. [Google Scholar]

- Karuna, C. Industry product market competition and managerial incentives. J. Account. Econ. 2007, 43, 275–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, K.M. Managerial incentives and product market competition. Rev. Econ. Stud. 1997, 64, 191–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hecker, D.E. High-technology employment: A broader view. Mon. Labor Rev. 1999, 122, 18–28. [Google Scholar]

- Amato, S.; Ricotta, F.; Basco, R. Family-managed firms, external sources of knowledge and innovation. Ind. Innov. 2022, 29, 701–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basco, R. The family’s effect on family firm performance: A model testing the demographic and essence approaches. J. Fam. Bus. Strategy 2013, 4, 42–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotlar, J.; De Massis, A.; Frattini, F.; Fang, H. Technology acquisition in family and nonfamily firms: A longitudinal analysis of Spanish manufacturing firms. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2013, 30, 1073–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duysters, G.; Lavie, D.; Sabidussi, A.; Stettner, U. What drives exploration? Convergence and divergence of exploration tendencies among alliance partners and competitors. Acad. Manag. J. 2020, 63, 1425–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyres, N.S.; Silverman, B.S. R&D, organization structure, and the development of corporate technological knowledge. Strateg. Manag. J. 2004, 25, 929–958. [Google Scholar]

- March, J.G. Exploration and exploitation in organizational learning. Organ. Sci. 1991, 2, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, J.; Liu, N. Exploitative and exploratory innovations in knowledge network and collaboration network: A patent analysis in the technological field of nano-energy. Res. Policy 2016, 45, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chacar, A.; Vissa, B. Are emerging economies less efficient? Performance persistence and the impact of business group affiliation. Strateg. Manag. J. 2005, 26, 933–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bromiley, P.; Harris, J.D. A comparison of alternative measures of organizational aspirations. Strateg. Manag. J. 2014, 35, 338–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Xie, E.; Fang, J.; Mei, N. Performance feedback and firms’ relative strategic emphasis: The moderating effects of board independence and media coverage. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 139, 218–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaroenjitrkam, A.; Yu, C.-F.; Zurbruegg, R. Does market power discipline CEO power? An agency perspective. Eur. Financ. Manag. 2019, 26, 724–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.; Porterfield, T.; Li, X. Impact of industry competition on contract manufacturing: An empirical study of US manufacturers. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2012, 138, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiken, L.S.; West, S.G.; Reno, R.R. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions; Sage Publications: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Brune, A.; Thomsen, M.; Watrin, C. Family firm heterogeneity and tax avoidance: The role of the founder. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2019, 32, 296–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).