How Does Revenue Diversification Affect the Financial Health of Sustainable Entrepreneurship Organizations in China? A Fuzzy Set Qualitative Comparative Analysis

Abstract

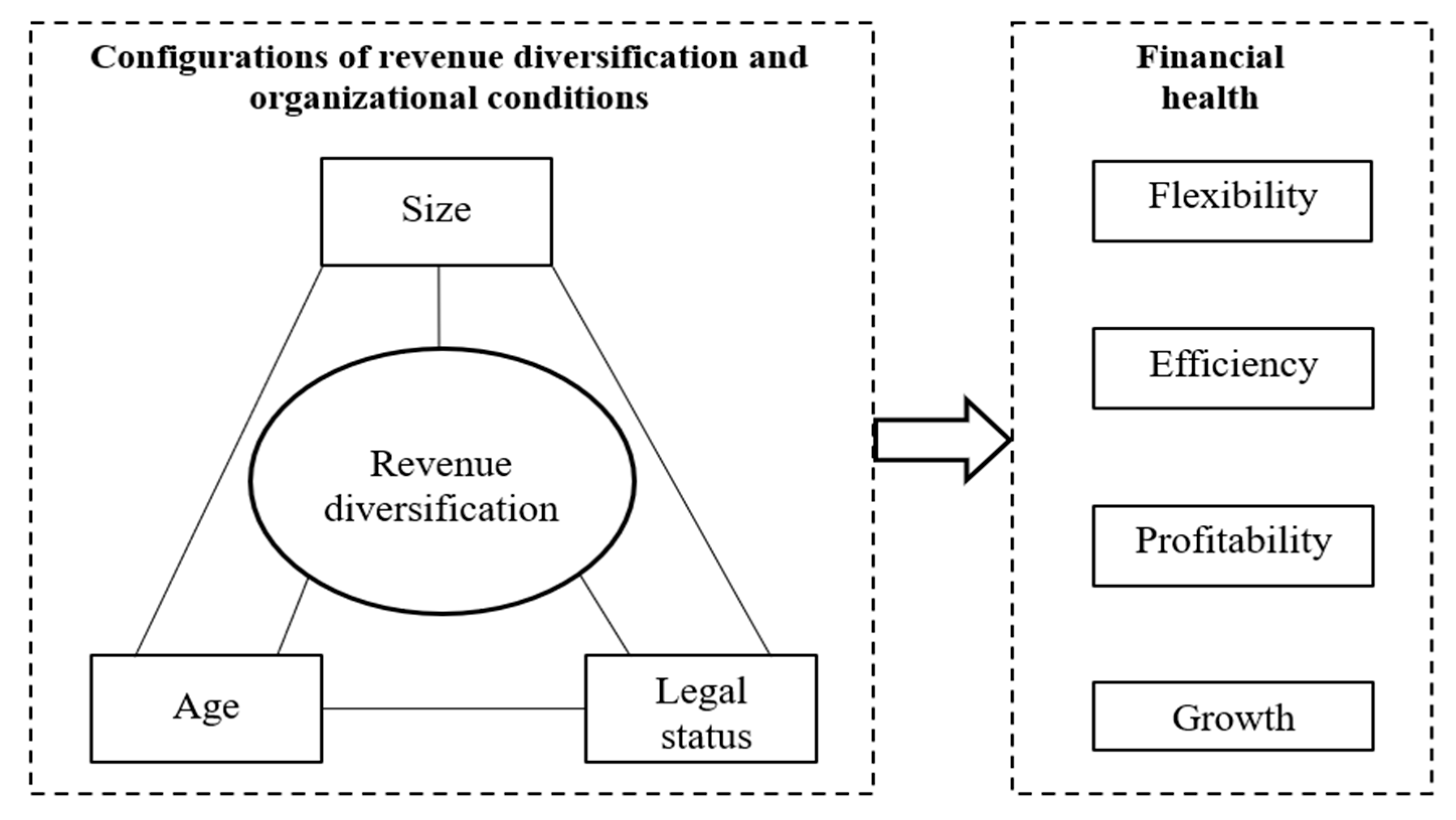

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Revenue Diversification and Financial Health

2.1.1. Financial Flexibility

2.1.2. Financial Efficiency

2.1.3. Profitability

2.1.4. Financial Growth

2.2. Impact of Organizational Characteristics

2.2.1. Effect of Organizational Size and Age

2.2.2. Effect of Legal Status

2.3. The Need for a Configurational Perspective

3. Methods

3.1. Sample

3.2. Measurements

3.2.1. Outcome

3.2.2. Conditions

3.3. Calibration

4. Results

4.1. Necessity Analysis

4.2. Sufficiency Analysis

4.3. Robustness Analysis

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

5.2. Practical Implications

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Muñoz, P.; Cohen, B. Sustainable entrepreneurship research: Taking stock and looking ahead. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2018, 27, 300–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosário, A.T.; Raimundo, R.J.; Cruz, S.P. Sustainable entrepreneurship: A literature review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarango-Lalangui, P.; Santos, J.L.S.; Hormiga, E. The development of sustainable entrepreneurship research field. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thananusak, T. Science mapping of the knowledge base on sustainable entrepreneurship, 1996–2019. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebhardt, L.; Kaus, J.; Hölze, K. Strategic agencement: How sustainable entrepreneurs address the dual liabilities of newness and otherness. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2025, 2483936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konys, A. Towards sustainable entrepreneurship holistic construct. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunçalp, D.; Yıldırım, N. Sustainable entrepreneurship: Mapping the business landscape for the last 20 years. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.M. Social enterprise in China: Driving forces, development patterns and legal framework. Soc. Enterp. J. 2011, 7, 9–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.M.; Bi, X.Y. The scaling strategies and the scaling performance of Chinese social enterprises: The moderating role of organizational resources. Entrep. Res. J. 2024, 14, 1701–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, X.Y.; Yu, X.M. The effects of scaling strategies on the scaling of social impact: Evidence from Chinese social enterprises. Nonprof. Manag. Lead. 2023, 33, 535–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Walid, L. The effects of entrepreneurs’ perceived risks and perceived barriers on sustainable entrepreneurship in Algeria’s SMEs: The mediating role of government support. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potluri, S.; Phani, B.V. Incentivizing green entrepreneurship: A proposed policy prescription (a study of entrepreneurial insights from an emerging economy perspective). J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 259, 120843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolthuis, R.; Klein, J.A. Sustainable entrepreneurship in the Dutch construction industry. Sustainability 2010, 2, 505–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, N.; Dousios, D.; Korfiatis, N.; Chalvatzis, K. Mapping the signaling environment between sustainability-focused entrepreneurship and investment inputs: A topic modeling approach. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2024, 33, 5405–5422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Zimmermann, A.; Marlow, S. Multilevel causal mechanisms in social entrepreneurship: The enabling role of social capital. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2025, 37, 460–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warnecke, T. Social entrepreneurship in China: Driving institutional change. J. Econ. Issues 2018, 52, 368–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.M.; Bi, X.Y. Scaling strategies, organizational capabilities and scaling social impact: An investigation of social enterprises in China. Ann. Public Coop. Econ. 2024, 95, 129–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardin, L. A variety of resource mix inside social enterprises. In Social Enterprises at the Crossroads of Market, Public Policies and Civil Society; Nyssens, M., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2006; pp. 111–136. [Google Scholar]

- Evers, A. The significance of social capital in the multiple goal and resource structure of social enterprises. In The Emergence of Social Enterprise; Borzaga, C., Defourny, J., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2001; pp. 296–311. [Google Scholar]

- Esteves, A.M.; Genus, A.; Henfrey, T.; Penha-Lopes, G.; East, M. Sustainable entrepreneurship and the sustainable development goals: Community-led initiatives, the social solidarity economy and commons ecologies. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2021, 30, 1423–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venegas-Flores, J.J.; Hernández-Ortiz, M.; Ortiz-Medica, I. Innovation in portfolio optimization through the use of genetic algorithms for sustainable entrepreneurship in volatile markets. Sci. Prax. 2024, 4, 61–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frumkin, P.; Keating, E.K. Diversification reconsidered: The risks and rewards of revenue concentration. J. Soc. Entrep. 2011, 2, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anton, C.E.; Zamfirache, A.; Albu, R.G.; Suciu, T.; Sofian, S.M.; Ghită-Pirnută, O.A. Sustainable entrepreneurship: Romanian entrepreneurs’ funding sources in the present-day context of sustainability. Sustainability 2024, 16, 654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, S.; Garg, I. Social entrepreneurship as a path for social change and driver of sustainable development: A systematic review and research agenda. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belz, F.M.; Binder, J.K. Sustainable entrepreneurship: A convergent process model. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2017, 26, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.P.; Hörisch, J. Reinforcing or counterproductive behaviors for sustainable entrepreneurship? The influence of causation and effectuation on sustainability orientation. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022, 31, 908–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaio, A.D.; Hassan, R.; Palladino, R. Sustainable entrepreneurship impact and entrepreneurial venture life cycle: A systematic literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 378, 134469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, W.J.; Wang, H.; Egginton, J.F.; Flint, H.S. The impact of revenue diversification on expected revenue and volatility for nonprofit organizations. Nonprof. Volunt. Sec. Q. 2014, 43, 374–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicker, P.; Longley, N.; Breuer, C. Revenue volatility in German nonprofit sports clubs. Nonprof. Volunt. Sec. Q. 2015, 44, 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abínzano, I.; López-Arceiz, F.J.; Zabaleta, I. Can tax regulations moderate revenue diversification and reduce financial distress in nonprofit organizations? Ann. Public Coop. Econ. 2023, 94, 301–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Los Mozos, I.S.L.; Rodríguez, D.A.; Rodríguez, R.Ó. Resource dependence in non-profit organizations: Is it harder to fundraise if you diversify your revenue structure? Voluntas 2016, 27, 2641–2665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Schnurbein, G.; Fritz, T.M. Benefits and drivers of nonprofit revenue concentration. Nonprof. Volunt. Sec. Q. 2017, 46, 922–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchard, M.J.; Rousselière, D. Do hybrid organizational forms of the social economy have a greater chance of surviving? An examination of the case of Montreal. Voluntas 2016, 27, 1894–1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, S.; Tian, S.; Deng, G. Revenue diversification or revenue concentration? Impact on financial health of social enterprises. Public Manag. Rev. 2021, 23, 754–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ecer, S.; Magro, M.; Sarpça, S. The relationship between nonprofits’ revenue composition and their economic-financial efficiency. Nonprof. Volunt. Sec. Q. 2017, 46, 141–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunetto, Y.; Xerri, M.; Farr-Wharton, B. The impact of management on NFP and FP social enterprises governed by government contracts and legislation. Public Manag. Rev. 2021, 23, 1217–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espasandín-Bustelo, F.; Rufino-Rus, J.I.; Rodríguez-Serrano, M.Á. Innovation and performance in social economy enterprises: The mediating effect of legitimacy for customers. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 158, 113626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.M. The governance of social enterprises in China. Soc. Enterp. J. 2013, 9, 225–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, V.K.; Pande, A.S. Making sustainable development happen: Does sustainable entrepreneurship make nations more sustainable? J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 440, 140849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.T.; Behl, A.; Pereira, V. Establishing linkages between circular economy practices and sustainable performance: The moderating role of circular economy entrepreneurship. Manag. Decis. 2024, 62, 2340–2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Re, B.; Magnani, G. Value co-creation processes in the context of circular entrepreneurship: A quantitative study on born circular firms. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 392, 135883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid, M.S.; Hossain, M.; Shahid, S.; Anwar, T. Frugal innovation as a source of sustainable entrepreneurship to tackle social and environmental challenges. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 406, 137050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zeng, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yu, S.; Wang, Z.; Deng, Y. Sustainable performance analysis and environmental protection optimization of green entrepreneurship-driven energy enterprises. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2025, 12, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Shen, W.; Qiu, Z.; Liu, R.; Mardani, A. Who are the green entrepreneurs in China? The relationship between entrepreneurs' characteristics, green entrepreneurship orientation, and corporate financial performance. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 165, 113960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesseh, P.K.; Lin, B.; Zhang, Y.; Wesseh, P.S. Sustainable entrepreneurship: When does environmental compliance improve corporate performance? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2024, 33, 3203–3221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tevel, E.; Katz, H.; Brock, D.M. Nonprofit financial vulnerability: Testing competing models, recommended improvements, and implications. Voluntas 2015, 26, 2500–2516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrett, J.L.; Hung, C. Does revenue concentration really bring organizational efficiency? Evidence from habitat for humanity. Nonprofit Volunt. Sec. Q. 2024, 53, 974–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicker, P.; Breuer, C. Examining the financial condition of sport governing bodies: The effects of revenue diversification and organizational success factors. Voluntas 2014, 25, 929–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimmon, E.; Spiro, S. Social and commercial ventures: A comparative analysis of sustainability. J. Soc. Entrep. 2013, 4, 182–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battilana, J.; Sengul, M.; Pache, A.C.; Model, J. Harnessing productive tensions in hybrid organizations: The case of work integration social enterprises. Acad. Manag. J. 2015, 58, 1658–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, D.; Berry, F.S. Can infused publicness enhance public value creation? Examining the impact of government funding on the performance of social enterprises in South Korea. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2021, 51, 167–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erpf, P.; Gmür, M.; Baumann-Fuchs, J. Does the business suit fit? Drivers for economic performance in social enterprises. J. Soc. Entrep. 2025, 16, 22–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.M.; Chen, K.; Liu, J.T. Exploring how organizational capabilities contribute to the performance of social enterprises: Insights from China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhou, Y. Business model innovation, legitimacy and performance: Social enterprises in China. Manag. Decis. 2021, 59, 2693–2712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahasranamam, S.; Lall, S.; Nicolopoulou, K.; Shaw, E. Founding team entrepreneurial experience, external financing and social enterprise performance. Brit. J. Manag. 2024, 35, 519–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragin, C.C. Redesigning Social Inquiry: Fuzzy Sets and Beyond; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Sinthupundaja, J.; Kohda, Y.; Chiadamrong, N. Examining capabilities of social entrepreneurship for shared value creation. J. Soc. Entrep. 2020, 11, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiss, P.C. Building better causal theories: A fuzzy set approach to typologies in organization research. Acad. Manag. J. 2011, 54, 393–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, E.; Prentice, C. Innovation and profit motivations for social entrepreneurship: A fuzzy-set analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 99, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, G.T.; Zachary, M.A.; LaFont, M. Configurational approaches to the study of social ventures. Res. Methodol. Strateg. Manag. 2014, 9, 111–146. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, Y.C.; Jang, J.H. Factors influencing the sustainability of social enterprises in Korea: Application of the QCA method. Int. J. u- e-Serv. Sci. Technol. 2016, 9, 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinhans, R.; Van Meerkerk, I.; Warsen, R.; Clare, S. Understanding the durability of community enterprises in England: Results of a fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis. Public Manag. Rev. 2023, 25, 926–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lückenbach, F.; Baumgarth, C.; Schmidt, H.J.; Henseler, J. To perform or not to perform? How strategic orientations influence the performance of social entrepreneurship organizations. Cogent. Bus. Manag. 2019, 6, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.M.; Xia, H.Y.; He, Y.J.; Chen, H.Y. The sustainability performance of social enterprises in China: The configurational impacts of ecosystems and revenue structures. Sustainability 2025, 17, 793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Li, P.; Zhao, G. What entrepreneurial ecosystem elements promote sustainable entrepreneurship? J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 422, 138459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pricopoaia, O.; Lupas, A.; Mihai, I.O. Implications of innovative strategies for sustainable entrepreneurship: Solutions to combat climate change. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greckhamer, T.; Furlani, S.; Fiss, P.C.; Aguilera, R.V. Studying configurations with qualitative comparative analysis: Best practices in strategy and organization research. Strateg. Organ. 2018, 16, 482–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leppänen, P.T.; McKenny, A.F.; Short, J.C. Qualitative comparative analysis in entrepreneurship: Exploring the technique and noting opportunities for the future. Res. Methodol. Strateg. Manag. 2019, 11, 155–177. [Google Scholar]

- Chikoto, G.L.; Ling, Q.; Neely, D.G. The adoption and use of the Hirschman–Herfindahl Index in nonprofit research: Does revenue diversification measurement matter? Voluntas 2016, 27, 1425–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, C.Q.; Wagemann, C. Set-Theoretic Methods for the Social Sciences: A Guide to Qualitative Comparative Analysis; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kerlin, J.A.; Lall, S.A.; Peng, S.; Cui, T.S. Institutional intermediaries as legitimizing agents for social enterprise in China and India. Public Manag. Rev. 2021, 23, 731–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, B.; Qureshi, I.; Riaz, S. Social entrepreneurship in non-munificent institutional environments and implications for institutional work: Insights from China. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 154, 605–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, R. Referee, sponsor or coach: How does the government harness the development of social enterprises? A case study of Chengdu, China. Voluntas 2021, 32, 1054–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beynon, M.; Jones, P.; Pickernell, D. Innovation and the knowledge-base for entrepreneurship: Investigating SME innovation across European regions using fsQCA. Entrep. Region. Dev. 2021, 33, 227–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Indicators | Measures |

|---|---|

| flexibility | net assets divided by total revenue [30] |

| efficiency | total expenditures divided by total revenues [35] |

| profitability | net income divided by total assets [30] |

| growth | growth rate in total revenue [32] |

| Descriptive Statistics | Calibration Values | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Min. | Max. | Mean | S. D. | F. M. | Cr. | F. N. | |

| flexibility | −13.25 | 108.70 | 2.63 | 9.98 | 1.21 | 0.44 | 0.10 |

| efficiency | 0.17 | 1.00 | 0.95 | 0.10 | 0.72 | 0.96 | 1.00 |

| profitability | 0.00 | 3.14 | 0.11 | 0.33 | 0.60 | 0.09 | 0.00 |

| growth | −0.98 | 11.50 | 0.77 | 1.44 | 0.79 | 0.24 | 0.00 |

| revenue diversification | 0.00 | 0.90 | 0.33 | 0.29 | 0.61 | 0.31 | 0.00 |

| age | 1.00 | 20.00 | 6.49 | 4.07 | 10.00 | 5.00 | 3.00 |

| size | 0.00 | 8.31 | 2.91 | 1.30 | 3.66 | 2.71 | 1.95 |

| legal status | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.40 | 0.49 | 1.00 | 0.50 | 0.00 |

| Flexibility | Efficiency | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | Low | High | Low | |||||

| Cons. | Cov. | Cons. | Cov. | Cons. | Cov. | Cons. | Cov. | |

| revenue diversification | 0.50 | 0.47 | 0.61 | 0.63 | 0.42 | 0.17 | 0.53 | 0.83 |

| ~revenue diversification | 0.61 | 0.59 | 0.48 | 0.52 | 0.58 | 0.24 | 0.47 | 0.76 |

| age (old) | 0.63 | 0.60 | 0.49 | 0.51 | 0.57 | 0.23 | 0.48 | 0.77 |

| ~age (old) | 0.49 | 0.47 | 0.62 | 0.65 | 0.43 | 0.18 | 0.52 | 0.82 |

| size (large) | 0.68 | 0.65 | 0.42 | 0.44 | 0.63 | 0.26 | 0.46 | 0.74 |

| ~size (large) | 0.42 | 0.39 | 0.67 | 0.70 | 0.37 | 0.15 | 0.54 | 0.85 |

| legal status (nonprofit) | 0.29 | 0.34 | 0.51 | 0.66 | 0.29 | 0.15 | 0.43 | 0.85 |

| ~legal status (nonprofit) | 0.71 | 0.57 | 0.49 | 0.43 | 0.71 | 0.25 | 0.57 | 0.75 |

| Profitability | Growth | |||||||

| High | Low | High | Low | |||||

| Cons. | Cov. | Cons. | Cov. | Cons. | Cov. | Cons. | Cov. | |

| revenue diversification | 0.40 | 0.13 | 0.53 | 0.87 | 0.56 | 0.53 | 0.57 | 0.58 |

| ~revenue diversification | 0.60 | 0.21 | 0.47 | 0.79 | 0.56 | 0.54 | 0.54 | 0.57 |

| age (old) | 0.55 | 0.19 | 0.49 | 0.81 | 0.43 | 0.41 | 0.68 | 0.71 |

| ~age (old) | 0.45 | 0.15 | 0.51 | 0.85 | 0.69 | 0.67 | 0.43 | 0.45 |

| size (large) | 0.65 | 0.22 | 0.47 | 0.78 | 0.52 | 0.50 | 0.57 | 0.59 |

| ~size (large) | 0.35 | 0.12 | 0.53 | 0.88 | 0.58 | 0.56 | 0.52 | 0.54 |

| legal status (nonprofit) | 0.34 | 0.15 | 0.41 | 0.85 | 0.35 | 0.42 | 0.46 | 0.58 |

| ~legal status (nonprofit) | 0.66 | 0.19 | 0.59 | 0.81 | 0.65 | 0.53 | 0.54 | 0.47 |

| Flexibility | Efficiency | Profitability | Growth | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | Low | Low | Low | High | Low | |||||||

| FH1 | FL1 | FL2 | EL1 | EL2 | EL3 | PL1 | PL2 | PL3 | GH1 | GL1 | GL2 | |

| revenue diversification | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||||||||

| age (old) | ● | Ⓧ | Ⓧ | Ⓧ | Ⓧ | |||||||

| size (large) | ● | Ⓧ | Ⓧ | Ⓧ | Ⓧ | Ⓧ | ||||||

| legal status (nonprofit) | Ⓧ | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |||||

| consistency | 0.819 | 0.813 | 0.849 | 0.869 | 0.886 | 0.887 | 0.904 | 0.902 | 0.917 | 0.813 | 0.818 | 0.795 |

| raw coverage | 0.168 | 0.350 | 0.227 | 0.347 | 0.252 | 0.295 | 0.346 | 0.246 | 0.155 | 0.277 | 0.292 | 0.190 |

| unique coverage | 0.168 | 0.166 | 0.042 | 0.205 | 0.043 | 0.105 | 0.206 | 0.105 | 0.031 | 0.277 | 0.157 | 0.053 |

| overall solution consistency | 0.819 | 0.802 | 0.864 | 0.891 | 0.813 | 0.806 | ||||||

| overall solution coverage | 0.168 | 0.393 | 0.561 | 0.482 | 0.277 | 0.347 | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yu, X.-M. How Does Revenue Diversification Affect the Financial Health of Sustainable Entrepreneurship Organizations in China? A Fuzzy Set Qualitative Comparative Analysis. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4377. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104377

Yu X-M. How Does Revenue Diversification Affect the Financial Health of Sustainable Entrepreneurship Organizations in China? A Fuzzy Set Qualitative Comparative Analysis. Sustainability. 2025; 17(10):4377. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104377

Chicago/Turabian StyleYu, Xiao-Min. 2025. "How Does Revenue Diversification Affect the Financial Health of Sustainable Entrepreneurship Organizations in China? A Fuzzy Set Qualitative Comparative Analysis" Sustainability 17, no. 10: 4377. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104377

APA StyleYu, X.-M. (2025). How Does Revenue Diversification Affect the Financial Health of Sustainable Entrepreneurship Organizations in China? A Fuzzy Set Qualitative Comparative Analysis. Sustainability, 17(10), 4377. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104377