Abstract

Responsible innovation originated from concerns about the responsibilities of technological innovation from a strategic and policy perspective in European and American countries in the early 21st century and has expanded to developing countries in recent years, becoming an essential path for global innovation transformation and sustainable development. However, with the deepening of enterprises’ positioning as the “main body of technological innovation”, theoretical research focusing on corporate responsible innovation (CRI) remains inadequate, and its driving mechanisms have yet to be clarified. Addressing this gap, we adopt an exploratory multiple-case study method, selecting three Chinese technology-innovative enterprises for grounded theory analysis, constructing a driving factor model through three-level coding. The findings reveal that instrumental motivation, relational motivation, and moral motivation constitute the internal driving factors of CRI; market pressure, policy pressure, and normative pressure constitute the external driving factors. When external pressure levels are high, they significantly enhance the effectiveness of internal motivations in driving responsible innovation. This study unveils the synergistic mechanism of multi-dimensional motivations and pressures, providing a theoretical framework and practical implications for guiding and driving enterprises to practice responsible innovation.

1. Introduction

With the increasing embeddedness of technological innovation in the process of social development, related ethical, safety, and negative externality issues—such as ethical controversies in gene editing, social labor displacement fears from AI applications, and privacy breaches in big data commercialization [1,2]—have become prominent. These events highlight societal concerns about the negative externalities of innovation and the ethical value of technological progress.

As the main entity of technological innovation, corporate innovation activities not only directly impact their own economic benefits and technological capabilities, but also bring developmental opportunities or societal challenges to public values. Corporate innovation outcomes are characterized by complexity and risk [3], and innovation dominated by enterprises often struggles to effectively address the societal risks posed by disruptive new technologies. As a novel governance approach for technological innovation, responsible innovation is recognized as an effective pathway to resolve these issues [4]. It reduces the uncertainty of innovation, enables innovation to genuinely drive growth, and achieves sustainable development embedded in societal visions [5]. Corporate responsible innovation (CRI) refers to an innovation process where enterprises adopt a win–win mindset to integrate stakeholders, aiming to achieve technological advancement and economic efficiency while adhering to ethical principles and satisfying societal expectations [6]. It emphasizes multi-stakeholder collaborative decision-making and proactive risk governance, steering innovation toward alignment with societal ethical imperatives through dynamic institutional frameworks. This approach ensures that technological advancements prioritize ethical alignment and societal well-being, ultimately fostering technology for good and advancing sustainable development goals.

However, promoting CRI remains challenging. First, although surveys indicate that enterprises may not necessarily innovate irresponsibly, the inherent uncertainty of innovation, the long-term lag in its outcomes, and insufficient awareness of innovation responsibility among some firms result in low recognition and acceptance of responsible innovation [7,8,9]. Second, discussions on the influencing factors and driving factors of CRI remain scarce in both academia and industry. Existing studies predominantly adopt singular perspectives, rarely systematically exploring the antecedents of CRI or considering interactions among different factors [10,11,12]. Therefore, this study addresses the gap by systematically examining the interactions among internal motivations and external pressures in driving CRI, and offering practical recommendations on policy enablers to accelerate CRI adoption and corporate strategies to institutionalize responsible innovation practices.

As a qualitative theoretical construction strategy, case study research can scientifically and effectively support research designs that require deriving theoretical frameworks from practical summarization and induction [13]. Given that research on CRI remains in its nascent exploratory stage, adopting an exploratory multiple-case study for theory building is both feasible and methodologically appropriate. Building on this rationale, this study conducts an exploratory case investigation of three Chinese technology innovation-oriented enterprises. Through grounded theory methodology and a rigorous multi-stage coding process, we systematically construct a driving factor model of CRI. This approach aims to provide theoretical underpinnings and practical implications for motivating enterprises to implement responsible innovation initiatives.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Corporate Responsible Innovation (CRI)

The negative externalities of technological innovation have prompted discourse on responsible innovation. As an emerging technological governance framework, responsible innovation has gained significant policy governance traction globally. Horizon 2020—the EU Framework Programme for Research and Innovation first introduced the concept of responsible innovation, emphasizing the establishment of open, interactive, and transparent innovation processes. Here, innovators and societal stakeholders jointly assume accountability to ethically align technological advancements with societal evolution, ensuring innovation outcomes meet ethical acceptability, sustainability, and societal expectations [14,15,16,17]. In China, the 13th Five-Year Plan for the National Science and Technology Innovation Plan explicitly promoted responsible innovation governance research and practice. The 2022 Guidelines on Strengthening Ethical Governance in Science and Technology further mandated “integrating ethical requirements throughout scientific research, technological development, and other scientific activities”, delineating actionable pathways for implementation. International organizations and nations are advancing responsible innovation governance strategies across legislative drafting, policy guidance, and ethics education, establishing multifaceted governance mechanisms spanning technological advancement [18], moral–ethical safeguards [19], institutional frameworks [20], and polycentric collaborative governance [21].

Academic research has evolved from analyzing the conceptual foundations of CRI to exploring governance frameworks and policy implications, ultimately converging on implementation challenges. Further focusing on enterprises as innovation actors, scholars have clarified responsible innovation’s key attributes in business contexts. It is characterized as a democratic, inclusive, and transparent approach where organizations collaborate with stakeholders to generate innovations that deliver positive social and environmental value while addressing grand societal challenges [22]. The essence of CRI lies in integrating multi-stakeholder perspectives into innovation systems (Inclusion), proactively anticipating potential adverse impacts (Anticipation), and institutionalizing reflective (Reflexivity) and adaptive governance mechanisms (Responsiveness) to maximize corporate growth and public value co-creation [6].

Recent studies increasingly link CRI to industry-specific governance frameworks [23,24,25] while emphasizing the alignment of innovation objectives and processes with measurable outcomes [26]. This dual focus enhances the feasibility of evaluating responsible innovation practices in corporate settings. However, theoretical research remains scarce on how CRI is implemented in enterprises, what drives firms to adopt CRI, and the specific strategies they employ. Simultaneously, CRI faces systemic challenges in practice: internally, collaborative decision-making mechanisms among stakeholders prolong innovation cycles and reduce efficiency, while dual constraints of endogenous risk management and social externality governance escalate costs and compress profit margins; externally, weak policy incentives, underdeveloped CRI ecosystems, and structural shortages in market investments hinder practical advancement [27]. Therefore, firm-led responsible innovation can only facilitate gradual adoption of responsible practices among stakeholders when CRI maturity is low [28].

These realities underscore the critical need to advance enterprise-level CRI research—both to deepen theoretical frameworks and to catalyze actionable solutions for real-world implementation.

2.2. Driving Factors of CRI

Research on the driving factors of CRI primarily examines organizational external and internal perspectives. From an external organizational standpoint, studies first adopt an organizational change lens, positing that confronting significant challenges constitutes a critical driver for enterprises to implement CRI [5,12,29,30]. Second, institutional theory perspectives emphasize that obtaining legitimacy and meeting stakeholder demands—including those from consumers and public entities—serve as pivotal driving factors [9,31,32,33]. CRI also represents a strategic response to external normative pressure. Compared to government-mandated “hard laws”, self-imposed “soft laws” enable firms to gain multi-stakeholder endorsement for socially or environmentally oriented practices, thereby flexibly addressing unforeseen negative consequences of innovation [10]. Additionally, securing cognitive legitimacy to attract investment motivates firms to adopt responsible innovation [34]. Internally, profit-seeking [11], activist advocacy [32], green creativity [35], responsible innovation awareness, and ethical codes of conduct [9,31,36] emerge as critical driving factors. Furthermore, firms can drive CRI implementation through cross-boundary search behaviors, which promote interdisciplinary collaboration and multi-stakeholder engagement, thereby expanding heterogeneous knowledge reservoirs to enhance responsible innovation capabilities [37]. A limited number of scholars have explored integrative models of these factors. First, instrumental motivation (e.g., profit maximization), relational motivation (e.g., voluntary compliance under regulatory pressure), and moral motivation (e.g., adherence to ethical norms) constitute three primary drivers [11], alternatively framed as economic/competitive, institutional/relational, and moral motivations [36]. Second, six factors—regulatory frameworks, financial resource availability, market orientation, customer knowledge, organizational structure, and knowledge-sharing among innovation partners—collectively influence the extent of CRI implementation [31].

Key barriers include conflicts between profit considerations and responsible innovation’s non-economic ethos [38], insufficient resources or institutionalized ethical governance [31], and incongruence between market-driven information asymmetry and responsible innovation’s demands for transparency and inclusivity [39]. The contextual dynamics may cause the same factor to function as either a driver or a barrier [31]. Furthermore, industry-specific characteristics significantly moderate the relationship between antecedents and CRI adoption [40]. For instance, highly regulated sectors like ICT-driven health innovations require tight alignment with responsible innovation principles [29].

Existing studies inadequately systematize contextual variables. Most adopt singular theoretical lenses, failing to holistically examine how multiple driving factors interact or jointly influence CRI. This fragmented approach hinders robust theoretical development and quantitative validation of antecedent mechanisms.

3. Research Design and Case Selection

3.1. Methodology

A case study, as a pivotal qualitative methodology in management studies, derives its core value from uncovering underlying mechanisms through systematic phenomenon observation [41]. It is particularly suited for emerging research domains where existing theories lack explanatory power. By addressing “how” and “why” questions [42], this approach effectively constructs theoretical frameworks, complementing quantitative methodologies. Given the nascent theoretical development of CRI, exploratory multiple-case study demonstrates strong methodological congruence.

However, case studies often focus on a limited number of representative cases, potentially constraining external validity; their causal inference may lack the empirical robustness of quantitative statistical methods; and they risk selection bias, subjective interpretation bias, and recall/reporting biases. To mitigate these methodological limitations and enhance the credibility of findings, we implement the following strategies:

- (1)

- Enhancing methodological rigor: case studies are categorized into three paradigms based on design objectives: exploratory (theory-building), explanatory (hypothesis-testing), and descriptive (theory-illustrating). Aligning with Berg’s (2005) recommendation to select three or more paradigmatic cases [43], this study adopts an exploratory multiple-case design. This strategy ensures both sample diversity for robust theory development and enhanced validity through cross-case comparisons.

- (2)

- Ensuring process transparency: all coding protocols, case selection criteria, and data analysis procedures are meticulously documented. Member checking among the research team is conducted to minimize subjective biases and enhance interpretative reliability.

3.2. Analytical Unit and Case Selection

The analytical unit—the focal entity bounding data collection—determines a case study’s precision and efficiency. Since CRI operates at the organizational level, this study designates firms as its analytical unit.

We employ a multiple-case approach to investigate the driving factors of CRI. This method prioritizes cross-case comparative validation, with cases selected through theoretical sampling to maximize representativeness and generalizability [44]. Three criteria guided our selection:

Typicality and representativeness: all cases are technology-driven innovators demonstrating pronounced responsible innovation practices. As industry pioneers whose founding timelines align with sector emergence, these firms exemplify sectoral leadership and evolutionary dynamics, enhancing findings’ reliability. Additionally, the three companies exhibit significant disparities in scale (with the latest published data indicating employee headcounts of 6258, 320, and 12,435, respectively), serving as representative cases of enterprises across varying sizes.

Cross-industry variation: the selected firms operate in distinct sectors—medical informatics, electronic bidding, and biopharmaceuticals—enabling comparative analysis to strengthen external validity. The similarity of their platform-based business models concurrently facilitates the construction of theoretical models. (See Table 1).

Table 1.

Basic information of case enterprises.

Data Accessibility: multi-source data availability critically impacts case study quality. Through institutional collaborations, we secured extensive primary data via CEO interviews and departmental engagements. Regarding secondary data collection, large-scale data scraping and analysis were systematically conducted. Listed companies (Winning Health and WuXi Biologics) were prioritized due to their greater accessibility to public disclosures, including sustainability reports, financial filings, and innovation-related regulatory submissions.

Winning Health Technology Group Co., Ltd. (“Winning Health”), headquartered in Shanghai, China, specializes in comprehensive digital healthcare solutions. With a mission to improve people’s health with the empowerment of technologies, it serves over 6000 medical institutions across China through 10 R&D centers and 20 branches. As a pioneer in internet-based medical services since 1994, the firm adheres to core values of “customer first, pursuit of excellency, innovation & solid, and pioneering spirit.” In the realm of responsible innovation, it is committed to driving industry-wide digital transformation, enhancing healthcare service quality, and elevating patient care experiences. Its product-driven strategy makes it into the International Data Corporation (IDC) global top 50 healthcare technology ranking list.

Shanghai E-Bidding Information Technology Co., Ltd. (“E-Bidding”) (Shanghai, China) integrates consultancy, software, and platform operations to build internet-enabled procurement ecosystems. In the realm of responsible innovation, E-Bidding adheres to client success and collaborative value-sharing as its core values, committed to building an internet-enabled procurement ecosystem and developing transparent e-procurement platforms. Commanding over 60% market share in enterprise electronic bidding platforms, it constructed six times more pilot platforms than its closest competitor. The firm’s founder co-drafted China’s Electronic Bidding Regulations and maintains leadership in regulatory compliance, earning recognition as an “Industry-Innovation Leader” and “China’s Most Innovative IT Enterprise”.

WuXi Biologics Co., Ltd. (“WuXi Biologics”) (Shanghai, China) is a leading global Contract Research, Development and Manufacturing Organization (CRDMO) offering end-to-end solutions that enable partners to discover, develop and manufacture biologics—from concept to commercialization—for the benefit of patients worldwide. WuXi Biologics supports 742 integrated client projects, including 16 in commercial manufacturing. Guided by its vision—“every drug can be made and every disease can be treated:”—the company is establishing an open access platform with the most comprehensive capabilities and technologies in the global biologics industry. This vision is operationalized through rigorous integration of ESG principles and actionable sustainability commitments. By aligning its innovation strategies with ethical imperatives, WuXi Biologics exemplifies its unwavering dedication to responsible innovation. It consistently earns accolades like “CMO Leader of the Year” and “ESG Industry Excellence Award”.

3.3. Data Collection and Analytical Approach

Following Yin (2003), both primary and secondary data were systematically collected in this study [13]. Primary data were obtained through in-depth interviews, while secondary data encompassed annual reports, corporate websites, media publications, industry research reports, and prior academic studies on the case enterprises. Data collection followed a systematic sequence: preliminary analysis of secondary data informed the design of interview protocols, followed by fieldwork implementation.

Given the case enterprises’ prolonged engagement in technology-driven responsible innovation, key informants included founders/CEOs, R&D executives, and directors of government affairs/policy research—individuals possessing comprehensive organizational insights and data access privileges. Supplementary interviews with personnel from R&D, ethics compliance, and market departments enhanced data validation. The interviews were conducted in a semi-structured format. Although semi-structured interviews employ pre-determined questions, the actual discussion trajectories may vary across interviewees based on their professional roles and experiential backgrounds. The interview process allows participants to elaborate on their personal experiences, perspectives, and emotions related to the subject matter. The interviewer’s role is to probe for granular details and seek clarifications when necessary to ensure accurate interpretation of responses, rather than imposing personal opinions or utilizing leading questions.

Semi-structured interviews addressed six core themes:

- (1)

- Company profiles and innovation strategies

Objective: understand the firm’s positioning and strategic priorities.

Sample Questions: Could you elaborate on your company’s core mission and how innovation aligns with its long-term vision? What are the key milestones in your innovation strategy development over the past five years? How do you allocate resources (financial, human, technological) to balance profit-driven and socially oriented innovation initiatives?

- (2)

- Implementation status of CRI

Objective: assess the operationalization of CRI.

Sample Questions: Could you provide concrete examples of CRI projects your company has implemented? How are their outcomes measured? What internal governance structures (e.g., ethics committees, sustainability departments) support CRI execution? Have you encountered challenges in aligning CRI with operational efficiency? How were these resolved?

- (3)

- Primary driving factors for adopting responsible innovation

Objective: identify internal/external catalysts for CRI adoption.

Sample Questions: What internal factors (e.g., leadership values) most strongly motivate your firm to pursue CRI? How do external pressures (e.g., regulatory compliance) shape your CRI priorities? In your view, do market rewards (e.g., brand reputation, customer loyalty) outweigh the costs of CRI implementation?

- (4)

- Stakeholders’ roles and influences on innovation processes

Objective: map stakeholder dynamics in innovation decision-making.

Sample Questions: Which stakeholders (e.g., investors, suppliers) exert the most influence on your innovation agenda? How is this managed? Could you describe the strategies your organization employs to ensure inclusive participation of underrepresented stakeholders in the collaborative design of CRI initiatives? Can you describe a situation where stakeholder feedback led to a significant pivot in an innovation project?

- (5)

- Industry-specific policy pressure

Objective: explore policy impacts on sectoral innovation practices.

Sample Questions: Which regulations (e.g., data privacy laws, environmental standards) most critically shape your CRI strategies in medical informatics/electronic bidding/biopharmaceuticals? How do you navigate conflicts between profit maximization and compliance with stringent policies like China’s Data Security Law? Have incentive policies (e.g., tax breaks for green tech) effectively stimulated your CRI investments?

- (6)

- Perceived societal values, moral constraints, and public expectations for corporate innovation

Objective: gauge alignment between innovation and socio-ethical norms.

Sample Questions: How does your firm interpret and prioritize societal values (e.g., equity, transparency) in innovation design? What moral dilemmas has your team faced when balancing commercial goals with public expectations (e.g., data ethics in healthcare)? How do you monitor and respond to shifting public perceptions of your innovations (e.g., third-party audits)?

Three rounds of interviews were conducted with each company, each targeting distinct organizational tiers and operational dimensions. The first interview (approximately 2 h), structured around the semi-structured guide, engaged senior executives (e.g., CEOs, CTOs) to explore strategic priorities, innovation governance, and CRI alignment with corporate missions. The second interview (approximately 1 h) shifted focus to operational validation, involving functional leaders (e.g., R&D directors) to scrutinize CRI implementation practices—including ethics review processes, sustainability compliance documentation, and challenges in balancing innovation efficiency with responsibility. Finally, the third interview (approximately 1 h) centered on stakeholder dynamics, with customer-facing department heads (e.g., marketing directors) providing insights into stakeholder expectation management, reputational risk mitigation, and mechanisms for integrating client feedback into CRI frameworks. This triphasic approach ensured multi-level data triangulation, capturing strategic intent, operational realities, and external accountability in CRI adoption.

The interviews were conducted face-to-face by the author, with two master’s students assisting in note-taking. Three to seven days prior to each interview, we provided interviewees with the interview guide and an estimated time commitment to ensure preparedness. At the outset of each session, we introduced the interview’s objectives and reiterated confidentiality assurances to alleviate participant apprehension, thereby fostering candid and authentic responses. After each session, interviewers engaged in a debriefing session to review and annotate the collected data, systematically coding key themes and stakeholder insights for subsequent analysis.

Secondary data analysis focused on financial reports, R&D documentation, innovation governance frameworks, ESG disclosures, and regulatory filings (e.g., Environmental Impact Assessment Public Participation Statements, Data Ethics Guidelines). Table 2 details data sources across cases.

Table 2.

Data sources for case enterprises.

The analytical approach employed grounded theory methodology, which directed the coding process through three iterative stages: open coding to conceptualize raw data into distinct categories, axial coding to identify relationships among these categories and form core constructs, and selective coding to establish causal logic and theoretical linkages between the constructs. This systematic approach facilitated a progressive abstraction from empirical observations to the development of a conceptual framework explaining the driving factors of CRI.

4. Data Analysis

4.1. Open Coding

Open coding constitutes the initial phase of the coding procedure, referring to the process of transforming raw case data into conceptualized constructs. The process entails three steps: (1) segmenting raw data and tagging statements relevant to CRI; (2) categorizing and abstracting tagged statements to derive initial concepts; and (3) grouping these concepts into coherent categories based on shared attributes. Applying this protocol to three case datasets, we extracted 50 initial concepts (aj) and 16 initial categories (Aj). Representative examples of open coding outcomes are presented in Table 3. Here, frequency refers to the statistical count of how often an initial concept appears within the qualitative dataset. Cross-case consistency denotes the stability with which initial categories recur across different cases.

Table 3.

Illustrative open coding results.

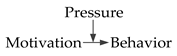

4.2. Axial Coding

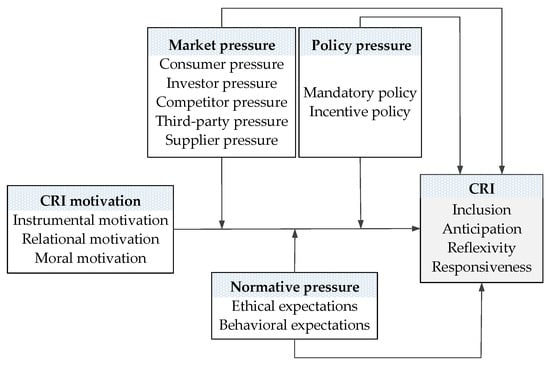

Axial coding builds upon the open coding framework by synthesizing phenomenological context and logical interdependencies among conceptual categories, ultimately consolidating them into core categories. Through iterative refinement of the 16 initial categories (Aj), we established 5 core categories (see Figure 1). Table 4 delineates these categories, their subcategories, and conceptual definitions.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework of core categories.

Table 4.

Axial coding results.

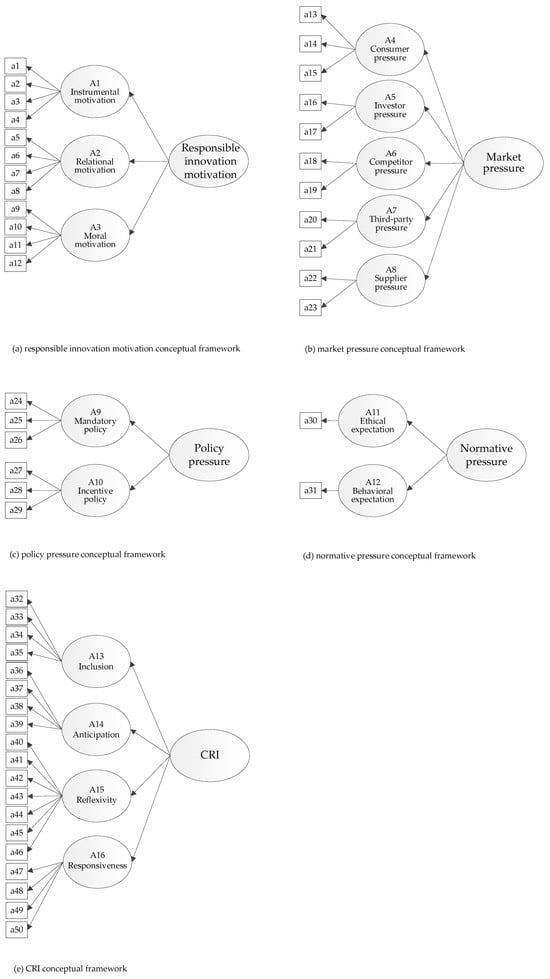

4.3. Selective Coding

Selective coding elucidates causal linkages among core constructs to formulate a theoretical framework. Comparative analysis against extant theories revealed a central “driving factor–behavior” logic: instrumental motivation, relational motivation, moral motivation, market pressure, policy pressure, and normative pressure collectively drive CRI (see Table 5). Specifically, instrumental/relational/moral motivation represent internal driving factors, market/policy/normative pressure constitute external driving factors, external pressures moderate the “motivation–behavior” relationship. This culminated in the CRI driving factor model, with construct relationships visualized in Figure 2.

Table 5.

Typical relational structures of core categories.

Figure 2.

Interlinkages and dynamics among core categories (CRI driving factor model).

4.4. Theoretical Saturation Test

Theoretical saturation was verified using reserved interview transcripts (n = 3) and supplementary secondary data, subjected to identical coding procedures (Open → Axial → Selective). No novel categories or relationships emerged beyond the proposed model, confirming saturation attainment.

5. Theoretical Model Elaboration

The analysis reveals that the CRI driving factor model effectively elucidates how instrumental motivation, relational motivation, moral motivation, market pressure, policy pressure, and normative pressure influence CRI, albeit through distinct mechanisms. We further contextualize the model through systematic engagement with empirical data, extant literature, and relevant theoretical frameworks (mainly including corporate motivation, stakeholder theory and new institutional theory).

5.1. CRI Motivation (Internal Driving Factors)

Instrumental motivation, relational motivation, and moral motivation collectively constitute internal driving factors that trigger CRI. Grounded in motivation theory [47], motivations are the cause and driving force that triggers behavior. They reflect enterprises’ conscious pursuit of strategic objectives. Case analyses demonstrate that whether and when firms adopt responsible innovation fundamentally depends on three need-based dimensions:

Instrumental motivation refers to firms leveraging responsible innovation as a strategic tool to achieve performance objectives while ensuring positive innovation outcomes. For example, Winning Health employs modularized product systems to flexibly address client needs while reducing customization costs, E-Bidding implements standardized procurement platforms to optimize operational efficiency, and WuXi Biologics invests in integrated R&D platforms to guarantee service quality and safety. This strategic alignment is supported by existing studies [48,49,50], which identify instrumental motivation as a dominant driver in commercial innovation contexts and a catalyst for responsible innovation [17]. Such motivation manifests in two distinct orientations [51]: short-term orientation, characterized by direct profitability enhancement through cost reduction strategies [52,53], and long-term orientation, which emphasizes voluntary self-regulation to cultivate sustainable business ecosystems [54]. Thus, instrumental motivation not only propels CRI for economic gains but also facilitates socio-ethical alignment, bridging profit imperatives with broader societal expectations.

Relational motivation drives firms to adopt responsible innovation as a strategic approach to cultivate stakeholder trust, expand resource networks, and strengthen platform ecosystems. For instance, Winning Health positions itself as a “trusted digital health service provider” to build credibility, E-Bidding develops interconnected procurement ecosystems to enhance transactional efficiency, and WuXi Biologics offers end-to-end biologics development services to empower global partners. Grounded in relational theory, this motivation emphasizes that stable partnerships reduce transaction costs and improve cooperation efficiency through relational commitment [55]. Under such motivation, firms prioritize stakeholder interest optimization, reconcile economic objectives with societal values, and pursue win–win outcomes [53]. To operationalize these goals, firms engage in three key practices: (1) maintaining transparent communication channels with stakeholders to ensure alignment, (2) tailoring innovation initiatives to meet stakeholder expectations, and (3) balancing profit-driven agendas with social responsibility imperatives. Thus, relational motivation fosters the development of collaborative ecosystems.

Moral motivation compels enterprises to engage in responsible innovation as an ethical imperative to fulfill societal obligations and align with universal moral principles. Exemplifying this commitment, case enterprises operationalize their missions through actionable strategies: Winning Health strives to “enhance healthcare accessibility and equity through technology-driven solutions”, E-Bidding enforces “transparent transactions and ethical commerce” to rebuild institutional trust, and WuXi Biologics advances its vision to “eliminate barriers in global drug development” by democratizing biopharmaceutical innovation. Ethically motivated firms, as moral agents [56], systematically integrate socio-ecological considerations into innovation lifecycles, transcending mere compliance to embody proactive stewardship. This entails three critical dimensions: (1) preemptively assessing ethical, ecological, and social risks through frameworks like responsible research and innovation, (2) prioritizing moral acceptability and sustainability as non-negotiable criteria for innovation outcomes, and (3) institutionalizing reflective practices to evaluate societal impacts, particularly during crises.

In conclusion, this study posits that CRI motivations serve as core triggering variables influencing enterprises to adopt responsible innovation practices. Instrumental, relational, and moral motivations exert a positive impact on CRI implementation. Whether driven by profit-oriented instrumental motives, relational motives aimed at enhancing stakeholder collaboration, or altruistic moral motives pursuing ethical imperatives, all three motivation types act as triggers for firms to initiate and sustain responsible innovation efforts.

5.2. CRI Pressure (External Driving and Amplifying Factors)

- (1)

- Driving Role of External Pressure

Market pressure, policy pressure, and normative pressure collectively serve as external driving factors for CRI. In dynamic market environments, firms face multi-stakeholder pressures—from consumers, investors, competitors, suppliers, NGOs, and governments—that shape innovation strategies. Policy pressure originates from governmental mandates, while market pressure stems from stakeholder demands mediated through market mechanisms. Normative pressure, reflecting societal value systems and behavioral norms, further constrains innovation trajectories.

Market pressures primarily manifest as demands, competition, resource constraints, and recognition from stakeholders regarding CRI, all of which directly impact corporate interests and undeniably serve as critical drivers for firms to implement CRI. Stakeholder theory posits that value creation lies not in short-term financial returns but in the long-term development of enterprises [57]. Firms must satisfy stakeholder demands to ensure survival and sustained success [58]. Key stakeholders—including consumers, investors, competitors, suppliers, and third-party organizations—provide sustained resource support to firms while their value propositions and demands incentivize firms to pursue optimal decision-making [26]. This dynamic not only encourages firms to prospectively and critically scrutinize the potential societal, environmental, political, and ethical impacts of their innovations but also compels them to reevaluate the moral acceptability and societal alignment of their practices. Consequently, stakeholder theory offers a robust theoretical foundation and analytical framework for studying CRI. The case-based analysis reveals the following concrete manifestations: Winning Health responds to market pressures such as hospital digitalization needs, patient demand for telemedicine, peer technological advancements, and requirements from partners (e.g., pharmaceutical firms, insurers) for stable health service platforms. These factors drive its focus on socially aligned innovation, evidenced by its inclusion in the “Exemplary Enterprises in Healthcare Sector of China’s IT Service Industry” list by CITSIA. E-Bidding capitalizes on growing demand for e-procurement systems and government e-platforms. By obtaining ISO 20000 (IT Service Management Systems Requirements) and ISO 27000 (Information Security Management Systems Requirements) certifications, it ensures operational stability, directly motivating CRI adoption. WuXi Biologics holds MSCI ESG ratings and over 10 certifications from global pharmaceutical regulatory authorities, as well as recognitions for exemplary corporate responsibility. This underscores the biopharmaceutical sector’s prioritization of third-party validation, which drives firms to embed social responsibility throughout the entire innovation lifecycle.

New institutional theory posits that the legitimacy mechanism is central to explaining corporate behavior. According to this theory, to secure support and resources within their embedded institutional environments, firms employ adaptive strategies and practices to achieve institutional legitimacy in specific domains [59]. Regulative elements—such as laws and regulations imposed by authoritative entities (e.g., states, governments) and normative elements—including societal values and role expectations, are pivotal in fostering organizational legitimacy [60]. These dual forces also serve as critical drivers for firms to adopt CRI practices [6].

Regarding policy pressure, institutional arrangements, legal frameworks, and enforcement mechanisms significantly influence corporate innovation strategies [61]. Studies classify government policy tools into coercive regulations and incentive-based mechanisms to examine their impact on innovation [62]. Mandatory policies, enforced through legal mandates, directly shape innovation strategies. For instance: Winning Health and E-Bidding, as typical “Internet+” enterprises, must comply with the Data Security Law of the People’s Republic of China, which imposes strict legal redlines on data security and user privacy. In E-Bidding’s e-procurement sector and WuXi Biologics’ biopharmaceutical domain, regulations such as the Measures for Electronic Bidding and the Drug Administration Law of the People’s Republic of China establish systematic and rigorous institutional requirements that critically inform innovation decisions. In contrast, incentive policies prioritize guidance and market alignment. While advancing administrative intervention, they harness market dynamics through flexible governance to stimulate innovation. For example, sector-specific promotion guidelines provide tax incentives, fiscal subsidies, and preferential loans for CRI, incentivizing firms to adopt CRI for sustainable growth.

Normative pressure arises from societal values, ethical constraints, and expectations for corporate accountability in innovation. Their core essence encompasses value systems and behavioral codes, which not only reflect stakeholder expectations but also bind all actors within the socio-economic ecosystem [63]. For instance, heightened societal emphasis on data security and medical privacy compliance, demands for bidding process efficiency and impartiality in bid evaluation outcomes, expectations for therapeutic efficacy, trial integrity, environmental stewardship in drug R&D, public scrutiny of innovation satisfaction and corporate reputation benchmarking collectively compel firms like Winning Health, E-Bidding, and WuXi Biologics to align with socially responsible norms and institutionalize CRI.

In conclusion, this study identifies market pressure, policy pressure, and normative pressure as the external drivers triggering firms’ adoption of CRI practices.

- (2)

- Amplifying Role of External Pressure

Market pressure, policy pressure, and normative pressure moderate the relationship between responsible innovation motivations and the activation of CRI, acting as amplifying factors that strengthen the impact of motivations on CRI intensity. Motivations serve as the causal impetus for organizational behavior, yet their translation into action requires contingent adaptation to contextual factors [64]. Across three cases, external pressures act as catalytic forces that strengthen the link between CRI motivations and actionable outcomes, demonstrating how contextual factors dynamically modulate organizational responses to innovation accountability. The following section provides a detailed analytical synthesis, integrating theoretical frameworks with existing empirical research to systematically examine the phenomena under investigation.

Market pressures significantly amplify the facilitative effects of CRI motivations. For instance, facing demands from consumers, investors, competitors, suppliers, and third par-ties, firms like Winning Health and E-Bidding strategically leverage CRI as a competitive differentiator to align with market needs and optimize stakeholder relations. Similarly, WuXi Biologics responds to intensifying sectoral pressures—including ESG rating benchmarks and global biopharma competition—by institutionalizing ethical R&D governance. This involves establishing cross-functional ethics review boards and prioritizing conflict-free supply chains, thereby embedding moral imperatives into its innovation lifecycle while mitigating regulatory and reputational risks.

First, consumers, as core stakeholders, exert pressure through their product choices, which play a pivotal role in incentivizing responsible innovation. With the acceleration of information exchange, consumers’ monitoring capabilities have intensified, compelling firms to proactively adopt CRI to safeguard social reputation and competitive resilience. Second, the rise of concepts such as responsible investment (ESG investing) and shifting investor preferences has elevated corporate sustainability to a critical criterion in investment evaluations, thereby compelling firms to sustain and deepen their commitment to CRI. Third, the intensity of industry competition shapes corporate strategies and behaviors [65]. Under high competitive pressure, firms increasingly leverage social responsibility initiatives to gain market legitimacy, thereby amplifying their commitment to CRI. Furthermore, when CRI becomes an industry norm, it fosters an ecosystem conducive to high-quality innovation. Firms are more likely to adopt CRI—whether for stakeholder recognition or altruistic purposes—to adapt to industry dynamics and secure competitive advantages [66]. Fourth, supplier pressure arises from requirements for product compatibility and selective partnership criteria. Aligning values with suppliers enhances a firm’s ability to consolidate and optimize supplier networks, strengthening resource integration. Finally, as industries grow in complexity, third-party organizations have emerged as key governance actors. Leveraging their expertise and authority, they monitor markets to uphold order and legitimacy [67]. By issuing certifications and evaluating CRI performance, third parties provide consumers with reliable signals of a firm’s commitment to responsible innovation [68]. Evidently, under high levels of market pressure, CRI driven by profit-oriented instrumental motivation, relational motivation to safeguard stakeholder relationships, and altruism-driven moral motivation is significantly amplified.

In the context of policy pressures, which constitute a critical situational variable for corporate innovation within the institutional environment [69], we posit that the impact of responsible innovation motivations on CRI implementation is moderated by policy pressures. Amidst evolving regulatory landscapes—exemplified by China’s Data Security Law—firms like E-Bidding and Winning Health strategically navigate dual policy pressures: coercive mandates (e.g., data compliance requirements) and incentive-based mechanisms (e.g., tax subsidies). By capitalizing on institutionalized carrot-and-stick approaches, they intensify motivation-driven CRI adoption—harnessing policy incentives (e.g., R&D grants) while preemptively mitigating regulatory risks (e.g., non-compliance penalties). Similarly, WuXi Biologics aligns its innovation strategies with policy imperatives, such as leveraging drug approval prioritization schemes under China’s pharmaceutical regulations to accelerate ethically compliant biopharmaceutical development. These cases collectively demonstrate how firms recalibrate CRI practices under heterogeneous policy pressures, transforming compliance challenges into strategic opportunities for sustainable growth.

First, policy pressures moderate the relationship between instrumental motivation and CRI. Governments’ progressive refinement of legal and regulatory frameworks has intensified the regulatory intensity over corporate innovation behaviors [70]. When firms recognize the mandatory requirements for CRI development at the national level, they integrate social responsibility into innovation strategies to secure long-term growth, actively pursuing CRI to enhance legitimacy and avoid political risks or legal sanctions from non-compliance. Incentive policies generate direct innovation compensation [71]. High levels of incentive policies effectively motivate firms to adopt CRI for long-term value creation. Additionally, these policies exhibit targeted specificity, directly offering subsidies, tax reductions, and low-interest loans to reward responsible innovation. Such measures not only mitigate CRI-associated risks but also incentivize proactive CRI engagement by aligning economic benefits with ethical imperatives.

Second, policy pressures moderate the relationship between relational motivation and CRI. Under high levels of mandatory policy pressures, governments constrain corporate innovation through mechanisms like mandatory production standards, compelling firms to align innovation activities within institutional frameworks to ensure innovation legitimacy and meet stakeholder demands [72]. In contrast, high levels of incentive policies optimize market mechanisms to guide and refine innovation behaviors among market entities. These policies incentivize firms to prioritize stakeholder needs and invest greater effort in stakeholder-collaborative innovation. By channeling innovation resources (e.g., technologies, knowledge) across industries, incentive policies reduce uncertainties associated with CRI. Strengthening stakeholder collaboration thus emerges as a critical pathway to mitigate such uncertainties, enabling firms to amplify innovation dynamism, leverage resource synergies.

Third, policy pressures moderate the relationship between moral motivation and CRI. For firms with strong moral motivation, mandatory policies not only legitimize their CRI endeavors but also confer institutional endorsement. Under high levels of mandatory policy pressures, strict regulatory oversight of innovation accountability compels morally driven firms to enhance awareness of social responsibility and intensify CRI implementation [51]. Conversely, incentive policies guide CRI adoption through direct resource compensation and adaptive flexibility. For innovations aligned with ethical norms and societal expectations, local governments may implement tax incentives, special fiscal subsidies, or low-interest loan programs [73]. These morally resonant incentives—akin to ethical rewards—ignite corporate senses of social responsibility and civic pride, motivating firms to voluntarily embed ethical imperatives into innovation processes and pursue CRI goals that satisfy moral acceptability thresholds.

Normative pressures significantly amplify the facilitative effects of CRI motivations. For instance, E-Bidding and Winning Health institutionalize rule-based compliance (e.g., transparent bidding protocols, data anonymization standards) to align with societal demands for data privacy and ethical innovation, thereby embedding normative expectations into their CRI frameworks to cultivate public trust. Similarly, WuXi Biologics responds to normative pressures—such as heightened public scrutiny of clinical trial integrity and environmental stewardship—by prioritizing quality assurance systems and adopting sustainability certifications. These cases collectively demonstrate how normative pressures act as both a catalyst, channeling diverse CRI motivations into context-specific practices that reconcile development motives with societal legitimacy.

First, the relationship between instrumental motivation and CRI may be moderated by normative pressures. Under high normative pressures, heightened societal attention to CRI amplifies mimetic convergence pressures as per new institutional theory [74]. To secure market dominance and profitability, firms proactively align with socially “responsible” norms, implementing CRI to enhance corporate performance and sustain long-term competitive advantages. Conversely, under low normative pressures, firms perceive weaker societal prioritization of responsible innovation principles, potentially diminishing attention to stakeholder concerns. Consequently, even if firms recognize CRI’s strategic benefits, instrumental motivation’s driving effect on CRI may attenuate due to insufficient normative imperatives.

Second, the relationship between relational motivation and CRI may be moderated by normative pressures. To pursue long-term development, firms must effectively manage stakeholder relationships—a priority that becomes pronounced under high normative pressures. According to stakeholder theory, corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives can partially fulfill stakeholder demands, fostering closer ties and enabling firms to secure scarce, non-substitutable resource advantages [75], thereby incentivizing CRI adoption. Under high normative pressures, firms prioritize social legitimacy and societal needs when formulating innovation strategies. Driven by relational motivation, they rigorously address stakeholder concerns and proactively integrate societal impact assessments into CRI processes. Conversely, under low normative pressures, diminished societal expectations for responsible innovation—evidenced by weaker public scrutiny, media oversight, and industry standards—reduce firms’ urgency to engage stakeholders. Although relational motivation may still spur CRI adoption in such contexts, its positive impact on CRI implementation is attenuated compared to high-pressure environments.

Third, the relationship between moral motivation and CRI may be moderated by normative pressures. Under high normative pressures, socially responsible innovation principles are widely endorsed. The socially shared expectation of voluntary social responsibility stewardship guides corporate innovation behaviors, compelling morally motivated firms to internalize “responsible” principles into corporate culture, autonomously implement CRI, and subject themselves to societal oversight [63]. Additionally, innovation responsibility education for managers and employees exerts a profound influence on firms. Under high normative pressures, socially oriented internal stakeholders (e.g., employees, executives) expect their firms’ innovations to proactively address societal challenges and create public value, thereby fulfilling their psychological and social needs for belongingness and security. Conversely, under low normative pressures, diminished societal attention to ethical imperatives in innovation processes results in slower CRI progression. Despite morally motivated firms continuing to advance CRI, its developmental trajectory remains less robust compared to contexts where societal prioritization of responsible innovation is pronounced.

In conclusion, high levels of market, policy, and normative pressures positively moderate the causal pathway from CRI motivations to implementation intensity. This amplification effect holds universally across firms—whether in medical informatics (Winning Health), electronic bidding (E-Bidding), or biopharmaceuticals (WuXi Biologics).

It is worth noting that high levels of mandatory policy pressures exert an absolute influence on triggering CRI driven by motivations, serving as the primary external driver for firms to deepen and operationalize responsible innovation practices. However, under low mandatory policy pressures, CRI initiatives stemming from non-moral motivations (e.g., instrumental or relational motives) may face significant implementation dilution, often resulting in superficial compliance or fragmented efforts. Meanwhile, the moral motivation for CRI demonstrates stable triggering effects on responsible innovation. Compared to extrinsic motivations—such as profit-oriented instrumental motives or stakeholder-centric relational motives—moral motivation, as an intrinsic driver, prioritizes the altruistic nature of innovation. This intrinsic focus renders it less vulnerable to external environmental pressures (e.g., regulatory laxity, market volatility), ensuring consistent ethical commitment even in contexts where extrinsic incentives wane.

6. Conclusions and Discussion

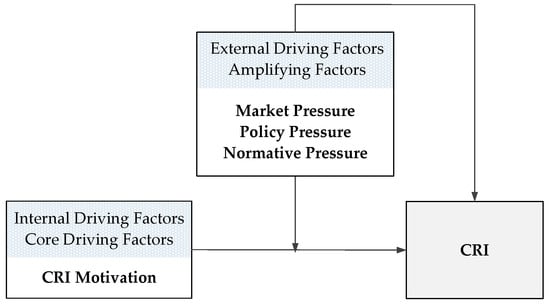

6.1. Conclusions

We conducted an exploratory case study on three technological enterprises—Winning Health, E-Bidding, and WuXi Biologics—to construct a CRI driving factor model through grounded theory methodology, including open coding, axial coding, and selective coding. The main conclusions are as follows (see Figure 3):

Figure 3.

Primary relationships of CRI driving factor model.

First, enterprises are the primary agents of responsible innovation, and their CRI motivation constitutes the core factor driving innovation behaviors. Case analyses demonstrate that CRI motivation manifests as instrumental motivation (profit-oriented goals), relational motivation (enhancing collaboration with key stakeholders), and moral motivation (altruistic purposes). Whether and when enterprises implement responsible innovation ultimately depends on their intrinsic needs. Consequently, CRI motivation serves as both the internal and central driving factor that compels firms to pursue responsible innovation for economic and societal benefits.

Second, external pressures drive enterprises to adopt responsible innovation. Market pressure stems from demands imposed by consumers, investors, competitors, third parties, and suppliers. Policy pressure operates through coercive regulations and incentive-based mechanisms that mandate or guide firms to implement responsible innovation. Normative pressure reflects societal moral and behavioral expectations for ethical innovation, prompting enterprises to internalize “responsible” principles into corporate culture. Thus, perceived external pressures function as critical external driving factors for triggering CRI.

Third, external pressures moderate the relationship between CRI motivation and implementation outcomes. High levels of market pressure, policy pressure, and normative pressure amplify the extent to which motivations translate into responsible innovation actions. Case analyses reveal that while CRI motivation remains the core driver, its transformation into practice requires contingent consideration of contextual factors—namely external pressures. Variations in pressure intensity directly influence how strongly motivations propel responsible innovation.

6.2. Implications

This study proposes a CRI driving factor model, offering a comprehensive theoretical lens for antecedent research. By systematically integrating internal and external driving factors, it addresses prior theoretical fragmentation and clarifies interactive mechanisms among multiple factors. Furthermore, it extends motivation theory to organizational innovation contexts, elucidating how “motivation → behavior” and “pressure → behavior” paradigms jointly shape responsible innovation. Through layered coding, this study establishes that CRI motivation serves as the core driver, moderated by external pressures—a finding consistent with theoretical frameworks emphasizing contextual contingencies in motivation-behavior linkages.

To promote CRI, governments should adopt a hybrid policy toolkit centered on incentives while integrating regulatory mandates and normative governance. First, a policy toolkit must be developed. Economic incentives through tiered tax reductions (e.g., tax cuts for firms with AA-level ESG ratings), targeted R&D subsidies (e.g., matching funds for green tech development), and low-interest loans must be enhanced. A “Responsible Innovation Fund” must also be established to support high-risk, ethics-sensitive sectors like biopharma and digital health, prioritizing projects such as AI ethics governance tools. Concurrently, the coercive policy design must be strengthened by embedding CRI metrics into industry access standards (e.g., requiring ISO 26000 [76] certification for new drug approvals) and implementing cross-departmental compliance audits (e.g., joint enforcement of data security and environmental laws) with escalating penalties and corrective guidance. Second, market pressure transmission mechanisms should be strengthened. Market pressures should be amplified through financial innovations: mandate listed firms must disclose “CRI Input-Output Ratios” in annual reports and introduce “CRI Bonds” for ethical tech R&D funding via green finance markets. CRI-certified suppliers should be prioritized in public procurement and require industry leaders to train supply chain partners in responsible practices. Third, institutional frameworks for normative pressures must be established. Normative pressures must be institutionalized by co-developing industry standards (e.g., medical AI ethics guidelines with China IT Services Innovation Alliance) and empowering NGOs to launch a “CRI Social Accountability Index”—publicly ranking firms akin to Carbon Disclosure Project-CDP’s carbon disclosure framework. Public participation mechanisms must be embedded, such as mandatory ethics hearings for gene-editing commercialization and government-run platforms enabling real-time consumer reporting of ethical concerns (e.g., data misuse complaints). This tripartite approach—blending policy, market, and norms forces—creates a self-reinforcing ecosystem for CRI.

To advance responsible innovation, enterprises should adopt a two-part strategy integrating motivational alignment and adaptive pressure response. First, CRI must be embedded into strategic DNA by aligning incentives across motivations: (1) instrumental motivation—link KPIs to ethical outcomes (e.g., tying product managers’ bonuses to customer privacy metrics) and develop CRI Profit & Loss Statements to quantify long-term gains like reduced regulatory fines and higher customer retention; (2) relational motivation—establish cross-functional CRI task forces (R&D, legal, CSR) to co-design solutions with key stakeholders through quarterly workshops and user co-creation labs; (3) moral motivation—mandate enterprise-wide CRI training (e.g., 20 h ethics certification for project eligibility) and tie executive compensation to CRI cultural metrics. Second, enterprises must dynamically adapt to external pressures. Enterprises dynamically respond to external pressures by aligning responsible innovation with market demands and shifting stakeholder preferences, proactively adapting to evolving consumer and investor expectations. To navigate policy pressures, enterprises simulate regulatory scenarios—such as stress-testing innovations against draft legislation—and participate in pilot initiatives (e.g., green technology hubs) to convert compliance into competitive advantages. In addressing normative pressures, enterprises lead industry ethics through transparent practices, such as publishing open-source sustainability guidelines and hosting public open days to demonstrate ethical operations like carbon-neutral supply chains. Concurrently, technological advancements—exemplified by E-Bidding’s end-to-end monitoring systems enabling real-time ethical oversight—and organizational reforms, including WuXi Biologics’s Ethics Review Board institutionalizing accountability, solidify the infrastructural backbone of CRI.

6.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

This study has limitations. First, the proposed model, derived from exploratory research, requires empirical validation to verify its reliability and generalizability the conceptual framework of CRI motivations and pressures, derived from exploratory multi-case research, necessitates empirical validation through large-scale quantitative studies or experimental designs to confirm its reliability and generalizability across industries. Second, reliance on cross-sectional data limits insights into the temporal evolution of CRI dynamics. Future research should adopt longitudinal designs to track how motivations and pressures interact across organizational lifecycles—particularly during crises (e.g., pandemics, regulatory shocks)—and how such interactions reshape innovation trajectories.

Additionally, future research could explore the following directions: First, developing standardized CRI assessment tools, such as a CRI Maturity Index that integrates ESG ratings, ethical audit scores, and stakeholder trust metrics to systematically benchmark progress and enable cross-industry comparisons; second, examining how multinational corporations navigate and harmonize divergent regulatory, cultural, and stakeholder expectations across global and local contexts through hybrid CRI strategies. By leveraging such hybridity, firms transform regulatory friction into strategic agility, achieving compliance without sacrificing innovation speed, while building reputational equity as globally responsible yet locally responsive actors.

Author Contributions

L.J. and J.Y. (Jiaojiao Yu) are the co-first authors of this article. Conceptualization, L.J., J.Y. (Jianxin You) and T.X.; methodology, L.J. and J.Y. (Jiaojiao Yu); writing—original draft preparation, L.J. and J.Y. (Jiaojiao Yu); writing—review and editing, T.X., J.Y. (Jianxin You) and Y.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The work was supported by 2024 Shanghai Municipal Science and Technology Innovation Action Plan—Soft Science Research Youth Project [24692107300], 2024 Shanghai Municipal Science and Technology Innovation Action Plan—Soft Science Research Project [24692112500].

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The cases data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Owen, R.; Goldberg, N. Responsible innovation: A pilot study with the UK engineering and physical sciences research. Risk Anal. 2010, 30, 1699–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goos, M.; Savona, M. The governance of artificial intelligence: Harnessing opportunities and mitigating challenges. Res. Policy 2024, 53, 104928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolz, K.; De Bruin, A. Responsible innovation and social innovation: Toward an integrative research framework. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 2019, 46, 742–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Poel, I.; Asveld, L.; Flipse, S.; Klaassen, P.; Scholten, V.; Yaghmaei, E. Company strategies for responsible research and innovation (RRI): A conceptual model. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schönherr, N.; Martinuzzi, A.; Jarmai, K. Towards a Business Case for Responsible Innovation. In Responsible Innovation SpringerBriefs in Research and Innovation Governance; Jarmai, K., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 85–97. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Jiang, L.; Yang, P.L. How to drive corporate responsible innovation? A dual perspective from internal and external drivers of environmental protection enterprises. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 10, 1091859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauttier, S.; Søraker, J.H.; Arora, C.; Brey, P.A.E.; Mäkinen, M. Models of RRI in Industry, Deliverable 3.3. Responsible Industry Project. 2017. Available online: https://www.responsible-industry.eu/ (accessed on 24 February 2025).

- Wezel, A.P.; Lente, H.V.; Sandt, J.; Bouwmeester, H.; Vandeberg, R.; Sips, A. Risk analysis and technology assessment in support of technology development: Putting responsible innovation in practice in a case study for nanotechnology. Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag. 2018, 14, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl, B.C.; Chatfield, K.; Holter, C.T.; Brem, A. Ethics in corporate research and development: Can responsible research and innovation approaches aid sustainability? J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 239, 118044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voegtlin, C.; Scherer, A.G. Responsible innovation and the innovation of responsibility: Governing sustainable development in a globalized world. J. Bus. Ethics. 2017, 143, 227–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaghmaei, E.; Van de Poel, I. Assessment of Responsible Innovation Methods and Practices, 1st ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK; Taylor & Francis Group: Abingdon, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Adomako, S.; Tran, M.D. Environmental collaboration, responsible innovation, and firm performance: The moderating role of stakeholder pressure. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022, 31, 1695–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods; Sage Publication: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Owen, R.; Macnaghten, P.; Stilgoe, J. Responsible research and innovation: From science in society to science for society, with society. Sci. Public Policy 2012, 39, 751–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Schomberg, R. A Vision of Responsible Innovation. In Responsible Innovation; Owen, R., Heintz, M., Bessant, J., Eds.; John Wiley: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Stilgoe, J.; Owen, R.; Macnaghten, P. Developing a framework for responsible innovation. Res. Policy 2013, 42, 1568–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandza, K.; Ellwood, P. Strategic and ethical foundations for responsible innovation. Res. Policy 2013, 42, 1112–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, D.; Brown, D.S.; Schrempf, B.; Kaplan, D. Responsible, inclusive innovation and the Nano-Divide. Nanoethics 2016, 10, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentley, S.V.; Schleiger, E.; McCrea, R.; Coates, R.; Hobman, E. Public perceptions of responsible innovation: Validation of a scale measuring societal perceptions of responsible innovation in science and technology. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2025, 210, 123849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.W.; Wang, G.Y. “Responsible Innovation” in Synthetic Biology. Bull. Chin. Acad. Sci. 2020, 35, 751–762. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Q.F.; Ren, J.L. Developing Responsible Digital Economy. Bull. Chin. Acad. Sci. 2021, 36, 823–834. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Jarmai, K.; Tharani, A.; Nwafor, C. Responsible Innovation in Business; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Owen, R.; Pansera, M.; Macnaghten, P.; Randles, S. Organisational institutionalisation of responsible innovation. Res. Policy 2021, 50, 104132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhmann, A.; Fieseler, C. Towards a deliberative framework for responsible innovation in artificial intelligence. Technol. Soc. 2021, 64, 101475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl, B.C. Responsible innovation ecosystems: Ethical implications of the application of the ecosystem concept to artificial intelligence. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2022, 62, 102441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehoux, P.; Silva, H.P.; Oliveira, R.R.; Rivard, L. The responsible innovation in health tool and the need to reconcile formative and summative ends in RRI tools for business. J. Responsible Innov. 2020, 7, 646–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Sun, X.R.; Lu, C.; Yu, X.Y.; Rong, K. Corporate Responsible Innovation: A Literature Review and Future Directions. Q. J. Manag. 2024, 9, 137–157+168–169. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Cao, X.; Li, W.J.; Xing, Z.Y.; Lv, D. Multi-Agent Cooperation Mechanism of Responsible Innovation. J. Syst. Manag. 2024, 33, 1521–1539. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chatfield, K.; Borsella, E.; Mantovani, E.; Porcari, A.; Stahl, B. An investigation into risk perception in the ICT industry as a core component of responsible research and innovation. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čeičytė, J. Implementing Responsible Innovation at the Firm Level; Kaunas University of Technology: Kaunas, Lithuania, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Auer, A.; Jarmai, K. Implementing responsible research and innovation practices in SMEs: Insights into drivers and barriers from the Austrian medical device sector. Sustainability 2018, 10, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldron, T.L.; Navis, C.; Karam, E.P.; Markman, G. Toward a theory of activist-driven responsible innovation: How activists pressure firms to adopt more responsible practices. J. Manag. Studies 2022, 59, 163–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaz, A.; Ali, F.H. What drives responsible innovation in polluting small and medium enterprises? An appraisal of leather manufacturing sector. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 43536–43553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwart, H.; Landeweerd, L.; Van Rooij, A. Adapt or perish? Assessing the recent shift in the European research funding arena from “ELSA” to “RRI”. Life Sci. Soc. Policy 2014, 10, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adomako, S.; Nguyen, N.P. Green creativity, responsible innovation, and product innovation performance: A study of entrepreneurial firms in an emerging economy. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2023, 32, 4413–4425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatfield, K.; Iatridis, K.; Stahl, B.; Paspallis, N. Innovating responsibly in ICT for ageing: Drivers, obstacles and implementation. Sustainability 2017, 9, 971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Zhang, L.T.; Lv, D. Research on the Relationship Between Boundary-spanning Search and Corporate Responsible Innovation—The Mediating Effect of Flexible Routine Replication and the Moderating Effect of Knowledge Field Activity. Manag. Rev. 2024, 36, 142–154. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Voegtlin, C.; Scherer, A.G.; Stahl, G.K.; Hawn, O. Grand societal challenges and responsible innovation. J. Manag. Stud. 2022, 59, 12785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, T.; Blok, V. Responsible innovation in business: A critical reflection on deliberative engagement as a central governance mechanism. J. Responsible Innov. 2019, 6, 4–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl, B.C.; Obach, M.; Yaghmaei, E.; Ikonen, V.; Chatfield, K.; Brem, A. The responsible research and innovation (RRI) maturity model: Linking theory and practice. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, P. Phenomenology: A new way of viewing organizational research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1982, 7, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platt, J. Case study in American methodological thought. Curr. Sociol. 1992, 40, 17–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, B.L. Qualitative Research Methods for the Social Science; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt, K.M. Building theories from case study research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO/IEC 20000-1:2018; Information Technology—Service Management. Part 1: Service management system requirements. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- ISO/IEC 27000; Information Security Management. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- Williams, M.; Burden, R.L. Psychology for Language Teachers: A Social Constructivist Approach. Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Pavie, X.; Scholten, V.; Carthy, D. Responsible Innovation: From Concept to Practice; World Scientific: Singapore, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Iatridis, K.; Schroeder, D. Responsible Research and Innovation in Industry: The Case for Corporate Responsibility Tools; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Blok, V.; Tempels, T.; Pietersma, E.; Jansen, L. Exploring ethical decision making in responsible innovation: The case of innovations for healthy food. In Responsible Innovation 3: A European Agenda? Asveld, L., Van Dam-Mieras, R., Swierstra, T., Lavrijssen, S., Linse, K., Van den Hoven, J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 209–230. [Google Scholar]

- Aguilera, R.V.; Rupp, D.E.; Williams, C.A.; Ganapathi, J. Putting the S back in corporate social responsibility: A multilevel theory of social change in organizations. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 836–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garriga, E.; Melé, D. Corporate social responsibility theories: Mapping the territory. J. Bus. Ethics 2004, 53, 51–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windolph, S.E.; Harms, D.; Schaltegger, S. Motivations for corporate sustainability management: Contrasting survey results and implementation. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2014, 21, 272–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuckler, D.; Nestle, M. Big food, food systems, and global health. PLoS Med. 2012, 9, e1001242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadaya, P. Determinants of the future level of use of electronic marketplaces: The case of Canadian firms. Electron. Commer. Res. 2006, 6, 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Hoven, J. Value Sensitive Design and Responsible Innovation. In Responsible Innovation: Managing the Responsible Emergence of Science and Innovation in Society; Owen, R., Bessant, J., Heintz, M., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 27–50. [Google Scholar]

- Bridoux, F.; Stoelhorst, J.W. Stakeholder theory, strategy, and organization: Past, present, and future. Strateg. Organ. 2022, 20, 797–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frooman, J. Stakeholder influence strategies. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1999, 24, 191–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, P.J.; Powell, W.W. The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1983, 48, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, W.R. Organisations and institutions. Res. Sociol. Organ. 1995, 2, 44–45. [Google Scholar]

- Eiadat, Y.; Kelly, A.; Roche, F.; Eyadat, H. Green and competitive? An empirical test of the mediating role of environmental innovation strategy. J. World Bus. 2008, 43, 131–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffe, A.B.; Newell, R.G.; Stavins, R.N. Technology policy for energy and the environment. Innov. Policy Econ. 2004, 4, 35–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garst, J.; Blok, V.; Jansen, L.; Omta, O. Responsibility versus profit: The motives of food firms for healthy product innovation. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Prajogo, D.; Oke, A. Supply chain technologies: Linking adoption, utilization, and performance. J. Supply Chain. Manag. 2016, 52, 22–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hojnik, J.; Ruzzier, M. The driving forces of process eco-innovation and its impact on performance: Insights from Slovenia. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 133, 812–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menguc, B.; Auh, S.; Ozanne, L. The interactive effect of internal and external factors on a proactive environmental strategy and its influence on a firm’s performance. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 94, 279–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, K.W.; Levi-Faur, D.; Snidal, D. Theorizing regulatory intermediaries: The RIT model. Ann. Am. Acad. Political Soc. Sci. 2017, 670, 14–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, D. Private facilitators of public regulation: A study of the environmental consulting industry. Regul. Gov. 2019, 15, 226–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambec, S.; Lanoie, P. Does it pay to be green? A systematic overview. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2008, 22, 45–62. [Google Scholar]

- Ford, J.A.; Steen, J.; Verreynne, M.L. How environmental regulations affect innovation in the Australian oil and gas industry: Going beyond the porter hypothesis. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 84, 204–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.M.; Xia, Q.; Xu, Y.D.; Hou, X.C. Industrial Technological Complexity, Government Subsidies and Corporate Green Technology Innovation Incentives. Nankai Bus. Rev. 2024, 27, 94–103+149+104–105. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.M.; Wu, D.H. Institutional Pressures on Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure and the Path Selection: A Framework Analysis from the Perspective of Institutional Isomorphism. J. Zhongnan Univ. Econ. Law 2015, 9, 55–62+159. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Cao, H.J.; Chen, Z.W. The Driving Effect of Internal and External Environment on Green Innovation Strategy: The Moderating Role of Top Management’s Environmental Awareness. Nankai Bus. Rev. 2017, 20, 95–103. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.W.; Liu, Y.X.; Chin, T.; Zhu, W.Z. Will green CSR enhance innovation? A perspective of public visibility and firm transparency. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrez, A. Social responsibility and competitiveness in hotels: The role of customer loyalty. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2020, 10, 1797–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 26000; Social Responsibility. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).