Harnessing Environmental Triggers to Shape Sports Tourists’ Sustainable Behavior: Evidence from Gilgit-Baltistan

Abstract

1. Introduction

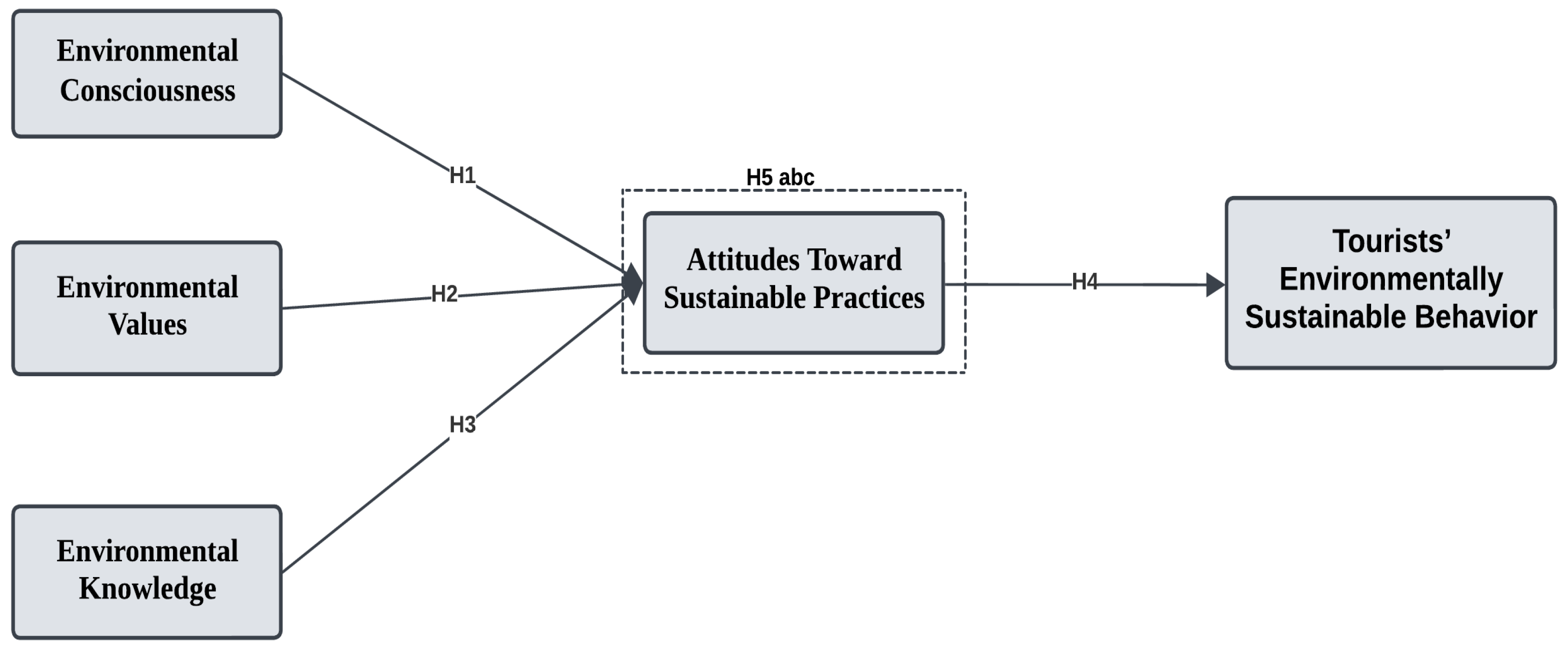

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Environmental Consciousness

2.2. Environmental Values

2.3. Environmental Knowledge

2.4. Tourists’ Environmentally Sustainable Behavior

2.5. Norm Activation Model

3. Hypotheses Formulation

3.1. Environmental Consciousness and Sustainable Practices

3.2. Environmental Values and Attitudes Toward Sustainable Practices

3.3. Environmental Knowledge and Sustainable Practices

3.4. Sustainable Practices and Sports Tourists’ Sustainable Behavior

3.5. The Mediating Role of Sustainable Practices

4. Methods

4.1. Sampling and Data Collection

4.2. Survey Development

4.3. Construct Measurement

4.4. Respondents’ Demographic Details

5. Data Analysis

5.1. Analysis of the Measurement Model

5.2. Analysis of the Structural Model

5.2.1. Hypothesis Testing

5.2.2. Direct Relationships

5.2.3. Mediation Relationships

6. Discussion and Implications

6.1. Theoretical Implications

6.2. Practical Implications

6.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xu, F.; Huang, L.; Whitmarsh, L. Home and away: Cross-contextual consistency in tourists’ pro-environmental behavior. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 1443–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, D. Sustainable mobility at the interface of transport and tourism: Introduction to the special issue on ‘Innovative approaches to the study and practice of sustainable transport, mobility and tourism’. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 129–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhutto, T.A.; Farooq, R.; Talwar, S.; Awan, U.; Dhir, A. Green inclusive leadership and green creativity in the tourism and hospitality sector: Serial mediation of green psychological climate and work engagement. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 29, 1716–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H.; Jan, F.-H.; Yang, C.-C. Conceptualizing and measuring environmentally responsible behaviors from the perspective of community-based tourists. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 454–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Scott, D.; Hall, C.M. Pandemics, tourism and global change: A rapid assessment of COVID-19. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 29, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodds, R.; Butler, R. The phenomena of overtourism: A review. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2019, 5, 519–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertocchi, D.; Camatti, N.; Giove, S.; van Der Borg, J. Venice and overtourism: Simulating sustainable development scenarios through a tourism carrying capacity model. Sustainability 2020, 12, 512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, E.; Fakfare, P. Overcoming “over-tourism”: The closure of Maya Bay. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2020, 6, 279–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, S.; Wangdus, J. Impact of overtourism on sustainable development and local community wellbeing in the Himalayan region. Int. J. Leis. Tour. Mark. 2022, 7, 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.; Merrilees, B.; Coghlan, A. Sustainable urban tourism: Understanding and developing visitor pro-environmental behaviours. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 26–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streimikiene, D.; Svagzdiene, B.; Jasinskas, E.; Simanavicius, A. Sustainable tourism development and competitiveness: The systematic literature review. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 29, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazza, B. A theoretical model of strategic communication for the sustainable development of sport tourism. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qasim, M.; Ahmed, Z. Adventure Tourism in Gilgit Baltistan Region: Opportunities, Trends and Destinations. Ann. Hum. Soc. Sci. 2022, 3, 44–54. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, A. Estimating the recreational value of mountain tourism to shape sustainable development in Gilgit-Baltistan, Pakistan. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 426, 138990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morfoulaki, M.; Myrovali, G.; Kotoula, K.-M.; Karagiorgos, T.; Alexandris, K. Sport tourism as driving force for destinations’ sustainability. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzeidi, M.; Moghimehfar, F. Environmental Aspects of Sport Tourism and Recreation. In International Perspectives in Sport Tourism Management; Routledge: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 46–57. [Google Scholar]

- Arshad, M.I.; Iqbal, M.A.; Shahbaz, M. Pakistan tourism industry and challenges: A review. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2018, 23, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, K.Z. CPEC issues and threatening cultural diversity in Gilgit-Baltistan. J. Punjab Univ. Hist. Soc. 2021, 34, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Passafaro, P. Attitudes and tourists’ sustainable behavior: An overview of the literature and discussion of some theoretical and methodological issues. J. Travel Res. 2020, 59, 579–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, Y.J.; Kim, W.G.; Lee, H.Y. Coffee shop consumers’ emotional attachment and loyalty to green stores: The moderating role of green consciousness. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 44, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motamedi-Barabadi, S.; Almeida-García, F.; Cortés-Macías, R. Influence of environmental attitudes in Iranian ecotourist behaviour. Cuad. Tur. 2023, 52, 285–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, S.R.; Uddin, M.A.; Bhattacharjee, S.; Dey, M.; Rana, T. Ecocentric leadership and voluntary environmental behavior for promoting sustainability strategy: The role of psychological green climate. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022, 31, 1705–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murtaza, S.H.; Khan, A.; Mustafa, S.M. Eco-centric success: Stakeholder approaches to sustainable performance via green improvisation behavior and environmental orientation in the hotel industry. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2024, 33, 7273–7286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, A. Tourism and the green economy: A place for an environmental ethic? Tour. Recreat. Res. 2013, 38, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Khan, A.N. Elucidating the effects of environmental consciousness and environmental attitude on green travel behavior: Moderating role of green self-efficacy. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 32, 2223–2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beall, J.M.; Boley, B.B.; Landon, A.C.; Woosnam, K.M. What drives ecotourism: Environmental values or symbolic conspicuous consumption? J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 29, 1215–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, M.A.; Seyfi, S.; Elhoushy, S.; Woosnam, K.M.; Patwardhan, V. Determinants of generation Z pro-environmental travel behaviour: The moderating role of green consumption values. J. Sustain. Tour. 2023, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godinho Filho, M.; Gonella, J.d.S.L.; Latan, H.; Ganga, G.M.D. Awareness as a catalyst for sustainable behaviors: A theoretical exploration of planned behavior and value-belief-norms in the circular economy. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 368, 122181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deplazes-Zemp, A. Beyond intrinsic and instrumental: Third-category value in environmental ethics and environmental policy. Ethics Policy Environ. 2024, 27, 166–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.C.; Wong, I.A.; Wu, S. The rising environmentalists: Fostering environmental goal attainment through volunteer tourism. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2023, 55, 482–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venugopal, K.; Ranganath, N.S. Eco-Conscious Travellers: Preferences and Perceptions of Homestay Accommodations. In Global Practices and Innovations in Sustainable Homestay Tourism; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2025; p. 203. [Google Scholar]

- Fawehinmi, O.; Yusliza, M.Y.; Mohamad, Z.; Noor Faezah, J.; Muhammad, Z. Assessing the green behaviour of academics: The role of green human resource management and environmental knowledge. Int. J. Manpow. 2020, 41, 879–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komolafe, A.A.; Adegboyega, S.A.-A.; Anifowose, A.Y.; Akinluyi, F.O.; Awoniran, D.R. Air pollution and climate change in Lagos, Nigeria: Needs for proactive approaches to risk management and adaptation. Am. J. Environ. Sci. 2014, 10, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolnicar, S.; Crouch, G.I.; Long, P. Environment-friendly tourists: What do we really know about them? J. Sustain. Tour. 2008, 16, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H. Consumer behavior and environmental sustainability in tourism and hospitality: A review of theories, concepts, and latest research. Sustain. Consum. Behav. Environ. 2021, 29, 1021–1042. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, T.H.; Fazia, C.; Abdelmoaty, M.A.; Bekzot, J.; Gozner, M.; Almakhayitah, M.Y.; Saleh, M.I.; Aleedan, M.H.; Abdou, A.H.; Salem, A.E. Sustainable pathways: Understanding the interplay of environmental behavior, personal values, and tourist outcomes in farm tourism. Discov. Sustain. 2024, 5, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, B.; Lee, M.J.; Chua, B.-L.; Han, H. An integrated framework of behavioral reasoning theory, theory of planned behavior, moral norm and emotions for fostering hospitality/tourism employees’ sustainable behaviors. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 34, 4516–4538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.; Pathak, G.S. Determinants of consumers’ green purchase behavior in a developing nation: Applying and extending the theory of planned behavior. Ecol. Econ. 2017, 134, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denley, T.J.; Woosnam, K.M.; Ribeiro, M.A.; Boley, B.B.; Hehir, C.; Abrams, J. Individuals’ intentions to engage in last chance tourism: Applying the value-belief-norm model. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 1860–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhang, J.; Cao, J.; Duan, X.; Hu, Q. The impact of behavioral reference on tourists’ responsible environmental behaviors. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 694, 133698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juvan, E.; Dolnicar, S. Drivers of pro-environmental tourist behaviours are not universal. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 166, 879–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, T.K.; Kumar, A.; Jakhar, S.; Luthra, S.; Garza-Reyes, J.A.; Kazancoglu, I.; Nayak, S.S. Social and environmental sustainability model on consumers’ altruism, green purchase intention, green brand loyalty and evangelism. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 243, 118575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolnicar, S. Designing for more environmentally friendly tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 84, 102933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juvan, E.; Dolnicar, S. The attitude–behaviour gap in sustainable tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2014, 48, 76–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. Normative influences on altruism. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1977; Volume 10, pp. 221–279. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, S.H.; Howard, J.A. A normative decision-making model of altruism. In Altruism and Helping Behavior: Social, Personality, and Developmental Perspectives; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1981; pp. 189–211. [Google Scholar]

- Jhawar, A.; Kumar, P.; Israel, D. Impact of materialism on tourists’ green purchase behavior: Extended norm activation model perspective. J. Vacat. Mark. 2023, 30, 841–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harland, P.; Staats, H.; Wilke, H.A. Situational and personality factors as direct or personal norm mediated predictors of pro-environmental behavior: Questions derived from norm-activation theory. Basic Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 29, 323–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Zhan, W. How to activate moral norm to adopt electric vehicles in China? An empirical study based on extended norm activation theory. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 3546–3556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, B.W.; Prideaux, B.; Thompson, M.; Demeter, C. Understanding tourists’ attitudes toward interventions for the Great Barrier Reef: An extension of the norm activation model. J. Sustain. Tour. 2022, 30, 1364–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, B.; Chua, B.-L.; Ryu, H.B.; Han, H. Volunteer tourism (VT) traveler behavior: Merging norm activation model and theory of planned behavior. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 1947–1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manosuthi, N.; Lee, J.-S.; Han, H. Predicting the revisit intention of volunteer tourists using the merged model between the theory of planned behavior and norm activation model. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2020, 37, 510–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadenne, D.L.; Kennedy, J.; McKeiver, C. An empirical study of environmental awareness and practices in SMEs. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 84, 45–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.H.A.; Al-Ghazali, B.M.; Bhatti, S.; Aman, N.; Fahlevi, M.; Aljuaid, M.; Hasan, F. The impact of Perceived CSR on employees’ pro-environmental behaviors: The mediating effects of environmental consciousness and environmental commitment. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Zhong, W.; Naz, S. Can environmental knowledge and risk perception make a difference? The role of environmental concern and pro-environmental behavior in fostering sustainable consumption behavior. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, M.; Rjoub, H.; Yesiltas, M. Environmental awareness and guests’ intention to visit green hotels: The mediation role of consumption values. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0248815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulzar, Y.; Eksili, N.; Koksal, K.; Celik Caylak, P.; Mir, M.S.; Soomro, A.B. Who Is Buying Green Products? The Roles of Sustainability Consciousness, Environmental Attitude, and Ecotourism Experience in Green Purchasing Intention at Tourism Destinations. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, S.; Ali, S.Z.; Khan, T.I.; Azam, K.; Afridi, S.A. Fostering sustainable tourism in Pakistan: Exploring the influence of environmental leadership on employees’ green behavior. Bus. Strategy Dev. 2024, 7, e328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamar, M.; Wirawan, H.; Arfah, T.; Putri, R.P.S. Predicting pro-environmental behaviours: The role of environmental values, attitudes and knowledge. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2021, 32, 328–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuadrado, E.; Macias-Zambrano, L.; Carpio, A.J.; Tabernero, C. The moderating effect of collective efficacy on the relationship between environmental values and ecological behaviors. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2022, 24, 4175–4202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, R.; van Riper, C.J.; Goodson, D.; Johnson, D.N.; Stewart, W. Learning pathways for engagement: Understanding drivers of pro-environmental behavior in the context of protected area management. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 323, 116204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solekah, N.A.; Handriana, T.; Usman, I. Environmental sustainability in Muslim-friendly tourism: Evaluating the influence of Schwartz’s basic value theory on tourist behaviour in Indonesia. Oppor. Chall. Sustain. (OCS) 2023, 2, 172–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, R.; Fajri, I. Differences in behavior, engagement and environmental knowledge on waste management for science and social students through the campus program. Heliyon 2022, 8, e08912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrukh, M.; Ansari, N.; Raza, A.; Wu, Y.; Wang, H. Fostering employee’s pro-environmental behavior through green transformational leadership, green human resource management and environmental knowledge. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 179, 121643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, S.A.; Khan, K.A. Impact of green human resource practices on hotel environmental performance: The moderating effect of environmental knowledge and individual green values. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 34, 2154–2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.-Y.; Liu, C.-H.; Horng, J.-S.; Chou, S.-F.; Ng, Y.-L.; Lin, J.-Y. Integrating the critical concepts of sustainability to predict sustainable behavior–the moderating role of information seeking. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeel, H.B.; Sabir, R.I.; Shahnawaz, M.; Zafran, M. Adoption of environmental technologies in the hotel industry: Development of sustainable intelligence and pro-environmental behavior. Discov. Sustain. 2024, 5, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fichter, T.; Martín, J.C.; Román, C. Young Segment Attitudes towards the Environment and Their Impact on Preferences for Sustainable Tourism Products. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdian, F.; Zahari, M.S.M.; Abrian, Y.; Wulansari, N.; Azwar, H.; Adrian, A.; Putra, T.; Wulandari, D.P.; Suyuthie, H.; Pasaribu, P. Driving Sustainable Tourism Villages: Evaluating Stakeholder Commitment, Attitude, and Performance: Evidence from West Sumatra, Indonesia. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, P.; Wang, W.; Yang, S. Doing the right thing: How to persuade travelers to adopt pro-environmental behaviors? An elaboration likelihood model perspective. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2024, 59, 191–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharmin, F.; Sultan, M.T.; Badulescu, A.; Bac, D.P.; Li, B. Millennial tourists’ environmentally sustainable behavior towards a natural protected area: An integrative framework. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahsan, M.J.; Ishaq, M.I.; Raza, A.; Talpur, Q.u.a. Let leaders permit nature! Role of employee engagement, environmental values, and sustainable behavioral intentions. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2024, 33, 7905–7921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazhenova, S.; Choi, J.-g.; Chung, J. International tourists’ awareness and attitude about environmental responsibility and sustainable practices. Glob. Bus. Financ. Rev. 2016, 21, 132–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosta, M.; Zabkar, V. Antecedents of environmentally and socially responsible sustainable consumer behavior. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 171, 273–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, S.; Greenwood, M.; Prior, S.; Shearer, T.; Walkem, K.; Young, S.; Bywaters, D.; Walker, K. Purposive sampling: Complex or simple? Research case examples. J. Res. Nurs. 2020, 25, 652–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qazi, W.; Qureshi, J.A.; Raza, S.A.; Khan, K.A.; Qureshi, M.A. Impact of personality traits and university green entrepreneurial support on students’ green entrepreneurial intentions: The moderating role of environmental values. J. Appl. Res. High. Educ. 2020, 13, 1154–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.-S.; Stepchenkova, S. Altruistic values and environmental knowledge as triggers of pro-environmental behavior among tourists. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 1575–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afroz, N.; Ilham, Z. Assessment of knowledge, attitude and practice of University Students towards Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). J. Indones. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2020, 1, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Su, K.; Chang, Y.; Wen, Y. Formation of environmentally friendly tourist behaviors in ecotourism destinations in China. Forests 2021, 12, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guenther, P.; Guenther, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Zaefarian, G.; Cartwright, S. Improving PLS-SEM use for business marketing research. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2023, 111, 127–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.; Alamer, A. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) in second language and education research: Guidelines using an applied example. Res. Methods Appl. Linguist. 2022, 1, 100027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M. “PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet”–retrospective observations and recent advances. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2023, 31, 261–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, R.F.; Miller, N.B. A Primer For Soft Modeling; University of Akron Press: Akron, OH, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wetzels, M.; Odekerken-Schröder, G.; Van Oppen, C. Using PLS path modeling for assessing hierarchical construct models: Guidelines and empirical illustration. MIS Q. 2009, 33, 177–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mataracı, P.; Kurtuluş, S. Sustainable marketing: The effects of environmental consciousness, lifestyle and involvement degree on environmentally friendly purchasing behavior. J. Glob. Sch. Mark. Sci. 2020, 30, 304–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez García de Leaniz, P.; Herrero Crespo, A.; Gómez López, R. Customer responses to environmentally certified hotels: The moderating effect of environmental consciousness on the formation of behavioral intentions. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 1160–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedlund, T. The impact of values, environmental concern, and willingness to accept economic sacrifices to protect the environment on tourists’ intentions to buy ecologically sustainable tourism alternatives. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2011, 11, 278–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansmann, R.; Laurenti, R.; Mehdi, T.; Binder, C.R. Determinants of pro-environmental behavior: A comparison of university students and staff from diverse faculties at a Swiss University. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 268, 121864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frick, J.; Kaiser, F.G.; Wilson, M. Environmental knowledge and conservation behavior: Exploring prevalence and structure in a representative sample. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2004, 37, 1597–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.H.; Moscardo, G. Understanding the impact of ecotourism resort experiences on tourists’ environmental attitudes and behavioural intentions. J. Sustain. Tour. 2005, 13, 546–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T.; Abel, T.; Guagnano, G.A.; Kalof, L. A value-belief-norm theory of support for social movements: The case of environmentalism. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 1999, 6, 81–97. [Google Scholar]

| Variables | Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|

| Total number of respondents | 302 | 100 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 193 | 63.9 |

| Female | 109 | 36.1 |

| Age group | ||

| 18 to 28 | 107 | 35.5 |

| 29 to 38 | 119 | 39.4 |

| 39 to 48 | 65 | 21.5 |

| Above 48 | 11 | 3.6 |

| Educational level | ||

| High school graduate or below | 14 | 4.6 |

| Technical/vocational school graduate | 33 | 10.9 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 179 | 59.2 |

| Master’s degree or higher | 76 | 25.1 |

| Monthly household income | ||

| Less than USD 70.97 | 19 | 6.2 |

| USD 70.97–106.45 | 123 | 40.7 |

| USD 106.45–141.93 | 63 | 20.8 |

| USD 141.93–177.41 | 25 | 8.2 |

| Above USD 177.41 | 72 | 23.8 |

| Occupation | ||

| Student | 90 | 29.8 |

| Government employee | 78 | 25.8 |

| Private employee | 61 | 20.2 |

| Entrepreneur | 73 | 24.2 |

| Constructs | FL | VIF | Alpha | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASTP | 0.72 | 0.84 | 0.64 | ||

| ATSP1 | 0.83 | 2.17 | |||

| ATSP2 | 0.85 | 2.23 | |||

| ATSP3 | 0.71 | 1.14 | |||

| ENCN | 0.81 | 0.88 | 0.72 | ||

| ENCN1 | 0.86 | 2.70 | |||

| ENCN2 | 0.82 | 2.42 | |||

| ENCN3 | 0.86 | 1.46 | |||

| ENKL | 0.89 | 0.93 | 0.82 | ||

| ENKL1 | 0.88 | 2.15 | |||

| ENKL2 | 0.92 | 3.38 | |||

| ENKL3 | 0.92 | 3.27 | |||

| ENVS | 0.84 | 0.90 | 0.76 | ||

| ENVS1 | 0.87 | 2.23 | |||

| ENVS2 | 0.86 | 2.14 | |||

| ENVS3 | 0.88 | 1.81 | |||

| TEFB | 0.70 | 0.81 | 0.52 | ||

| TEFB1 | 0.70 | 1.29 | |||

| TEFB2 | 0.74 | 1.32 | |||

| TEFB3 | 0.72 | 1.29 | |||

| TEFB4 | 0.71 | 1.30 |

| Heterotrait–Monotrait (HTMT) Ratio | Fornell and Larcker Method | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | ATSP | ENCN | ENKL | ENVS | TEFB | Variables | ATSP | ENCN | ENKL | ENVS | TEFB |

| ATSP | ATSP | 0.804 | |||||||||

| ENCN | 0.676 | ENCN | 0.558 | 0.850 | |||||||

| ENKL | 0.684 | 0.741 | ENKL | 0.554 | 0.672 | 0.909 | |||||

| ENVS | 0.672 | 0.847 | 0.737 | ENVS | 0.537 | 0.730 | 0.655 | 0.872 | |||

| TEFB | 0.834 | 0.773 | 0.808 | 0.738 | TEFB | 0.595 | 0.615 | 0.634 | 0.580 | 0.721 | |

| Variables | R2 | Q2 | Model Fit | Variables | f2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATSP | 0.381 | 0.367 | SRMR | 0.910 | ATSP -> TEFB | 0.54 |

| TEFB | 0.356 | 0.365 | NFI | 0.748 | ENCN -> ATSP | 0.38 |

| GOF | 0.495 | ENKL -> ATSP | 0.59 | |||

| ENVS -> ATSP | 0.22 |

| Hypotheses | Beta | T Values | p Values | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Relationships | ||||

| H1 ENCN -> ATSP | 0.241 | 3.923 | 0.302 | Not Supported |

| H2 ENVS -> ATSP | 0.182 | 2.747 | 0.006 | Supported |

| H3 ENKL -> ATSP | 0.273 | 3.885 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H4 ATSP -> TEFB | 0.595 | 12.71 | 0.000 | Supported |

| Indirect Relationships | ||||

| H5a ENCN -> ATSP -> TEFB | 0.144 | 3.613 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H5b ENVS -> ATSP -> TEFB | 0.108 | 2.692 | 0.007 | Supported |

| H5c ENKL -> ATSP -> TEFB | 0.162 | 3.483 | 0.001 | Supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ying, W.; Bostani, A.; Murtaza, S.H.; Ali, A. Harnessing Environmental Triggers to Shape Sports Tourists’ Sustainable Behavior: Evidence from Gilgit-Baltistan. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4291. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104291

Ying W, Bostani A, Murtaza SH, Ali A. Harnessing Environmental Triggers to Shape Sports Tourists’ Sustainable Behavior: Evidence from Gilgit-Baltistan. Sustainability. 2025; 17(10):4291. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104291

Chicago/Turabian StyleYing, Wang, Ahmed Bostani, Syed Hussain Murtaza, and Anwar Ali. 2025. "Harnessing Environmental Triggers to Shape Sports Tourists’ Sustainable Behavior: Evidence from Gilgit-Baltistan" Sustainability 17, no. 10: 4291. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104291

APA StyleYing, W., Bostani, A., Murtaza, S. H., & Ali, A. (2025). Harnessing Environmental Triggers to Shape Sports Tourists’ Sustainable Behavior: Evidence from Gilgit-Baltistan. Sustainability, 17(10), 4291. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104291