1. Introduction

Since the implementation of the economic reform and opening-up policy in 1978, China has attracted significant foreign direct investment (FDI), which has played a transformative role in addressing capital shortages, enhancing technological capabilities, and accelerating economic modernization and internationalization. However, due to significant differences in institutional environments, industrial foundations, and factor endowments, the spillover effects of inward FDI (IFDI) on the local economy in China exhibit marked regional heterogeneity [

1]. The eastern region, characterized by well-functioning market mechanisms, a favorable business environment, and a high degree of openness, has attracted the majority of IFDI [

2]. This has facilitated industrial upgrading, enhanced technological spillovers, and promoted sustainable development. In contrast, the central and western regions have lagged behind in attracting IFDI, largely due to less efficient resource allocation and weaker absorptive capacities for foreign technology and knowledge [

3]. As a result, the positive spillovers of IFDI on local economic development in these regions tend to exhibit diminishing marginal returns.

Innovative entrepreneurship is vital for the modern economy and society, which has been closely related to local economic growth and sustainable development [

4]. So, we narrow down to the effects of IFDI on domestic firms’ innovative entrepreneurial activities, the results are often inconsistent. Some scholars revealed positive spillover effects of IFDI in stimulating innovative entrepreneurial activities in host countries [

5], others argued that the impacts are negative [

6], and some suggested no significant effects exist [

7]. Scholars expressed skepticism about the existence of FDI spillovers, noting that their presence depends on specific conditions such as the characteristics of individual firms, industry sectors, and national regulations [

8]. This divergence underscores the need to examine the contextual factors that shape FDI spillovers, particularly in developing countries like China, where institutional environments and economic conditions differ significantly from those in developed economies [

9].

Studies on other developing countries, such as Brazil and Vietnam, underscored that IFDI alone is insufficient to guarantee the realization of spillover effects; instead, the institutional environment serves as a crucial enabling factor. For instance, empirical evidence from Brazilian regions (2003–2014) highlighted that the effectiveness of spillovers on regional innovation depends heavily on the alignment between IFDI and local institutional capabilities [

10]. Similarly, Nguyen [

11] used panel data from 52 Vietnamese provinces during 2005–2014 and found that the relationship between FDI and private investment is significantly moderated by the degree of market-based institutional development. Munemo [

12] employed panel data from 92 developing countries, arguing that the ability of IFDI to crowd-in business start-ups significantly depends on financial market development in the host economy. These studies collectively suggest that institutions do not merely provide a passive context for IFDI to stimulate economic activities but actively shape the channels through which spillover effects occur. Moreover, institutional environments exert heterogeneous influences on IFDI spillovers, depending on nations’ level of development and structural characteristics. Slesman et al. [

13] indicated that not all countries benefit equally from IFDI; it is primarily those with advanced institutional development that can effectively absorb positive spillovers, which otherwise might adversely impact the relationship between IFDI and entrepreneurship in host countries. Developing countries typically feature weak economic and governmental institutional structures, ongoing development, continuously evolving institutions, and higher receptiveness to change [

14].

Scholars agree on the moderating role of institutional environments in shaping the spillover effects of IFDI [

11,

15]. However, we still have a limited understanding of whether institutions can indirectly influence the relationship between IFDI and innovative entrepreneurship [

12]. Current research has predominantly focused on the firm-level absorptive capacity, highlighting how local firms’ abilities in R&D, human capital integration, and knowledge transformation determine the extent to which they benefit from FDI spillovers [

10]. While informative, this micro-level lens overlooks the institutional dimension of absorptive capacity—specifically, the extent to which economic institution facilitates the absorption, transformation, and transmission of IFDI. Building on these debates, this study introduces marketization as a proxy for institutional absorptive capacity and develops a novel mechanism model: IFDI → marketization → innovative entrepreneurship. Contrary to absorption at the firm level, marketization reflects an institutionalized form of capacity that enables regions to internalize the competitive pressures, regulatory frameworks, and technological spillovers associated with IFDI. This institutional process, in turn, contributes to optimizing market mechanisms, improving institutional quality, enhancing resource allocation efficiency, and reducing transaction costs—thereby fostering innovative entrepreneurship in an indirect but systematic manner.

In our empirical modeling, we use panel data from 30 Chinese provinces for the period 2010–2018 and employ a hierarchical fixed-effect mediation analysis. Our findings show that IFDI has a positive and significant spillover effect on innovative entrepreneurship in China, but no significant mediating effect of marketization. Regional heterogeneity analyses further reveal that IFDI has a positive and significant spillover effect on innovative entrepreneurship and marketization in the eastern regions, with marketization playing a partially mediating role. However, in the central region and western region, the mediating effect of marketization is absent. Based on the empirical findings, this study makes several important contributions. First, it moves beyond the conventional firm-level perspective on absorptive capacity by introducing the concept of institutional absorptive capacity and empirically verifies the mediating role of marketization in linking IFDI to regional innovative entrepreneurship. This offers a fresh theoretical lens to understand how IFDI can indirectly contribute to entrepreneurial development through institutional channels. Second, our empirical analysis reveals significant spatial heterogeneity of the institutional absorption mechanism, highlighting the uneven capacity of regions at different stages to internalize and transform FDI spillovers. Third, by focusing on China—the world’s largest developing economy—this study not only responds to the urgent policy question of how developing countries can more effectively absorb IFDI for endogenous innovation but also provides a useful reference for other economies undergoing institutional transformation. By emphasizing the foundational role of institutional capacity and market-oriented reform, the findings offer valuable implications for constructing a high-quality, open institutional framework that promotes inclusive and sustainable development.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 reviews prior studies, proposes the research hypotheses, outlines the research model, and

Section 3 describes the sample data and research methodology.

Section 4 presents our empirical results.

Section 5 discusses the empirical results, and

Section 6 concludes the paper.

2. Literature Review and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Concepts of IFDI’s Spillovers and Institutions’ Absorptive Capacity

IFDI exerts both direct and indirect impacts on host countries. While direct effects include job creation and increased exports [

16], its most significant long-term value often lies in spillover effects—externalities that influence domestic firms, industries, and institutions [

17]. IFDI can improve the host country’s macro-environment by stimulating infrastructure, enhancing market efficiency, and promoting legal and institutional reform [

1,

18,

19]. These improvements gradually diffuse to industries and individuals, enabling domestic firms to adopt foreign technologies and practices, boosting productivity and innovation [

20], and increasing entrepreneurial opportunities through better human capital and labor mobility [

21,

22].

However, whether these spillovers can be fully realized depends on the

absorptive capacity within a country—their ability to assimilate, adapt, and apply foreign knowledge [

23]. Absorptive capacity can manifest at the individual level [

24], enterprise or organizational level [

25], and national level [

15]. A higher national level, particularly with mature economic and government institutions, enhances this absorptive capacity [

15]. In contrast, weak institutions may hinder the transmission of FDI benefits, limiting their impact on innovative entrepreneurship [

26]. Theoretically, as a crucial externality influencing the absorptive capacity of host country institutions, IFDI directly impacts economic and governmental institutions, as they can increase efficiency by accelerating knowledge learning and the uptake of technological changes [

9].

2.2. IFDI and Economic Institution

North defined institutions as human-invented constraints that structure political, economic, and social interactions, often conceptualized as the “rules of the game”. Economic institutions, on the other hand, specifically aim to reduce uncertainty by creating a stable framework governed by the rules of human interaction [

27]. Most literature explored the quality of the host country’s institutions as a critical variable in the host country’s ability to attract IFDI [

26,

28,

29,

30]. IFDI can indirectly or directly influence these “rules of the game,” thereby shaping the institutional environment in the host country [

14].

Previous empirical evidence highlighted that IFDI may serve as an external driver for institutional transformation. Chen et al. [

31] pointed out that IFDI in China has promoted institutional improvement by demanding fairer, more efficient, and more transparent market competition, thereby enhancing the absorptive capacity associated with marketization. Meanwhile, IFDI facilitates the optimization of resource allocation, supports reforms in labor and personnel systems, and triggers institutional learning processes and financial deepening [

32]. It may also lead to the refinement of legal and tax systems by incentivizing government reform [

33]. However, this positive effect is not universal. In some African countries, despite the growing interest in IFDI for institutional reforms, considering the mixed nature of IFDI, the overall impact on the government institutions of African countries has not been significantly positive [

14]. Furthermore, excessive capital inflows and the emergence of oligopolistic industries can lead to liquidity challenges for the financial market [

9], thus negatively affecting the financial market development of the host country.

Additionally, while scholars generally agreed on the spillovers of IFDI on China’s economic activities, it is also a classical truth that IFDI is mainly clustered in the eastern coastal regions and some central regions [

2]. A plausible explanation for this phenomenon is that there is better infrastructure, stronger policy support, and a higher concentration of well-educated and skilled labor in these regions [

1]. In contrast, the western region faces greater institutional barriers, weaker legal frameworks, and limited government support, making it difficult to fully absorb the positive spillovers of IFDI. Previous studies in different countries also confirmed that the host country’s institutional environment has a threshold for absorbing potential spillovers from IFDI [

12]. Scholars have also shown that countries with underdeveloped institutions often fail to effectively benefit from the growth potential of IFDI [

34,

35,

36]. Huynh [

26] further noted the widespread prevalence of underground economic activities in developing countries, which bypass formal institutional processes and reflect weak institutions, ultimately obstructing the formation of institutional absorption mechanisms.

While the existing literature has provided valuable insights into how IFDI influences institutional environments—particularly in terms of government institutions, legal systems, and financial markets—our study seeks to extend this line of inquiry by focusing on marketization as a fundamental yet underexplored dimension of economic institutions. Based on prior empirical evidence, we attempt to clarify the mechanisms through which IFDI may influence market-oriented institutional transformation, thereby enhancing the institutional absorptive capacity of the host country. Furthermore, recognizing the varying levels of institutional development and regional disparities across China, we also try to explore how this relationship may differ across eastern, central, and western regions. Based on the above, this study proposes the following hypotheses:

H1a: IFDI positively or negatively affects the absorptive capacity of China’s overall economic institution (marketization).

H1b: IFDI positively or negatively affects the absorptive capacity of the economic institution (marketization) in the eastern region.

H1c: IFDI positively or negatively affects the absorptive capacity of the economic institution (marketization) in the central region.

H1d: IFDI positively or negatively affects the absorptive capacity of the economic institution (marketization) in the western region.

2.3. Economic Institution and Innovative Entrepreneurship

Innovation is not only an imperative part of a country’s economic growth but also a distinct component of entrepreneurship [

5]. It must be acknowledged that the expected benefits of entrepreneurship primarily stem from a few innovative, high-growth firms rather than the moderate growth in employment and revenue of newly established enterprises after overcoming survival difficulties [

37]. While factors affecting domestic innovative entrepreneurship can be attributed to various firm-specific or entrepreneur-specific aspects, how macro approaches, such as institutional development, support or suppress innovative entrepreneurial behavior is also a hotly debated area of academic research.

The macro approach seeks to establish and maintain an institutional environment in which innovative entrepreneurship can flourish [

38]. An effective economic institution that encourages capital formation, attracts international capital, allows for broad freedom of experimentation and creativity, ensures that new firms have the opportunity to compete in the marketplace, and promotes the positive development of innovative entrepreneurial activities in the country [

38,

39,

40]. In particular, an economic institution with secure property rights, well-functioning laws, free and open markets, and stable monetary arrangements facilitates savings, capital formation, and international investment, including R&D. At a more targeted level, laws and regulations that make entrepreneurship easy, protect innovation, allow for skilled labor mobility, encourage FDI in high-potential early-stage entrepreneurial firms, and allow for the reallocation of inefficiently used resources through bankruptcy [

41,

42,

43]. However, countries with low institutional quality have failed to encourage entrepreneurship. For example, when regulatory institutions are bureaucratic and complex, corruption is prevalent in government agencies, and excessive informal economic institutions replace formal institutions [

44]. They encourage rent-seeking behaviors that divert resources away from productive activities, increase the cost of doing business, and therefore, are not conducive to innovative entrepreneurship [

45]. In addition, poor economic institutions do not provide adequate stimulus mechanisms, thus blocking the ability of firms to innovate and reduce innovative entrepreneurial [

46,

47].

Cross-national studies have provided further empirical evidence. Sendra-Pons et al. [

47], based on data from 48 countries, demonstrated that differences in institutional development significantly shape the trajectory of innovative entrepreneurship. While sound economic institutions dominate in developed countries, developing countries tend to exhibit underdeveloped economic institutions, and such institutional gaps usually limit further innovative entrepreneurial development [

48,

49]. Manimala and Wasdani [

50] also identified the prevalence of weak institutions such as unclear policies, insufficient governance, and inhibitory cultures in emerging economies, which adversely affect innovative entrepreneurship. Beyond that, as we mentioned earlier, institutions in developing countries are still evolving and undergoing change. Internal frictions and contradictions arising from institutional change also negatively impact domestic innovative entrepreneurial activities [

51].

Therefore, it is helpful to extend the above experiences from cross-nation to regions at different stages of development within the same country. Economic institutions play an essential role in boosting domestic innovative entrepreneurship. However, regions with better economic development tend to have well-developed institutional environments that positively stimulate local innovative entrepreneurship; while regions with less advanced economic development are in no position to bring favorable assistance to innovative entrepreneurship. We propose the following hypotheses:

H2a: The economic institution (marketization) positively or negatively affects China’s overall domestic innovative entrepreneurship.

H2b: The economic institution (marketization) positively or negatively affects innovative entrepreneurship in the eastern region.

H2c: The economic institution (marketization) positively or negatively affects innovative entrepreneurship in the central region.

H2d: The economic institution (marketization) positively or negatively affects innovative entrepreneurship in the western region.

2.4. Mediating Role of Economic Institution in the Relationship Between IFDI and Innovative Entrepreneurship

IFDI can foster the absorptive capacity of economic institutions, particularly by advancing the marketization process, thereby promoting the development of innovative entrepreneurship. Marketization, as a process of institutional evolution, refers to the extent to which market mechanisms dominate resource allocation in economic activities, with its core being the establishment of an open, transparent, and fair institutional environment [

52]. Under a high level of marketization, foreign knowledge, and technology introduced by IFDI are more easily absorbed and utilized, facilitating institutional learning and technological upgrading [

9,

26,

51,

53].

IFDI has contributed to the deepening of China’s marketization process through the provision of capital, technology, and advanced concepts of institutional development. This has enabled economic institutions to learn and assimilate best practices, directly contributing to the further development of marketization and institutions’ absorptive capacity. The higher the absorptive capacity of marketization is, the easier international capital formation, broader experimentation and creativity freedom, and innovation protection are. All of which lower entry barriers and stimulate innovative entrepreneurship [

38,

40,

43]. Moreover, a higher level of marketization’s absorptive capacity facilitates the reallocation of resources to high-efficiency sectors, increases incentives for private R&D, and promotes the formation of dynamic, innovation-driven entrepreneurial firms. Conversely, a weaker level of marketization, characterized by excessive government intervention, regulatory opacity, and rent-seeking behaviors, often leads to monopolistic practices, misallocation of capital, and an increase in the cost of doing business, and deterring innovation does not provide an adequate incentive [

9,

45,

47]. At this point, marketization prevents the positive spillover effects of IFDI, in turn, presents extreme challenges to domestic firms that are unable to pursue innovative research and development activities in a troubled market environment, thus hampering the expansion of innovative entrepreneurship.

As a result, IFDI can either enhance or reduce an economic institution’s absorptive capacity, leading to a corresponding impact on domestic innovative entrepreneurship. When the absorptive capacity of marketization increases, innovative entrepreneurship is stimulated. Specifically, when IFDI improves the absorptive capacity of marketization, it can effectively facilitate the transmission of spillover effects; thus, innovative entrepreneurship is stimulated. When IFDI fails to sufficiently strengthen the marketization absorptive capacity, it hinders innovative entrepreneurship since the spillovers may not be effectively transmitted. Moreover, due to the significant regional disparities across China, IFDI influences the strength of marketization’s absorptive capacity in different areas, leading to heterogeneous mediating mechanisms in the eastern, central, and western regions. Therefore, we propose the following hypotheses:

H3a: Marketization has a mediating effect on the relationship between overall IFDI and innovative entrepreneurship in China.

H3b: Marketization has a mediating effect on the relationship between IFDI and innovative entrepreneurship in eastern China.

H3c: Marketization has a mediating effect on the relationship between IFDI and innovative entrepreneurship in central China.

H3d: Marketization has a mediating effect on the relationship between IFDI and innovative entrepreneurship in western China.

2.5. Research Model

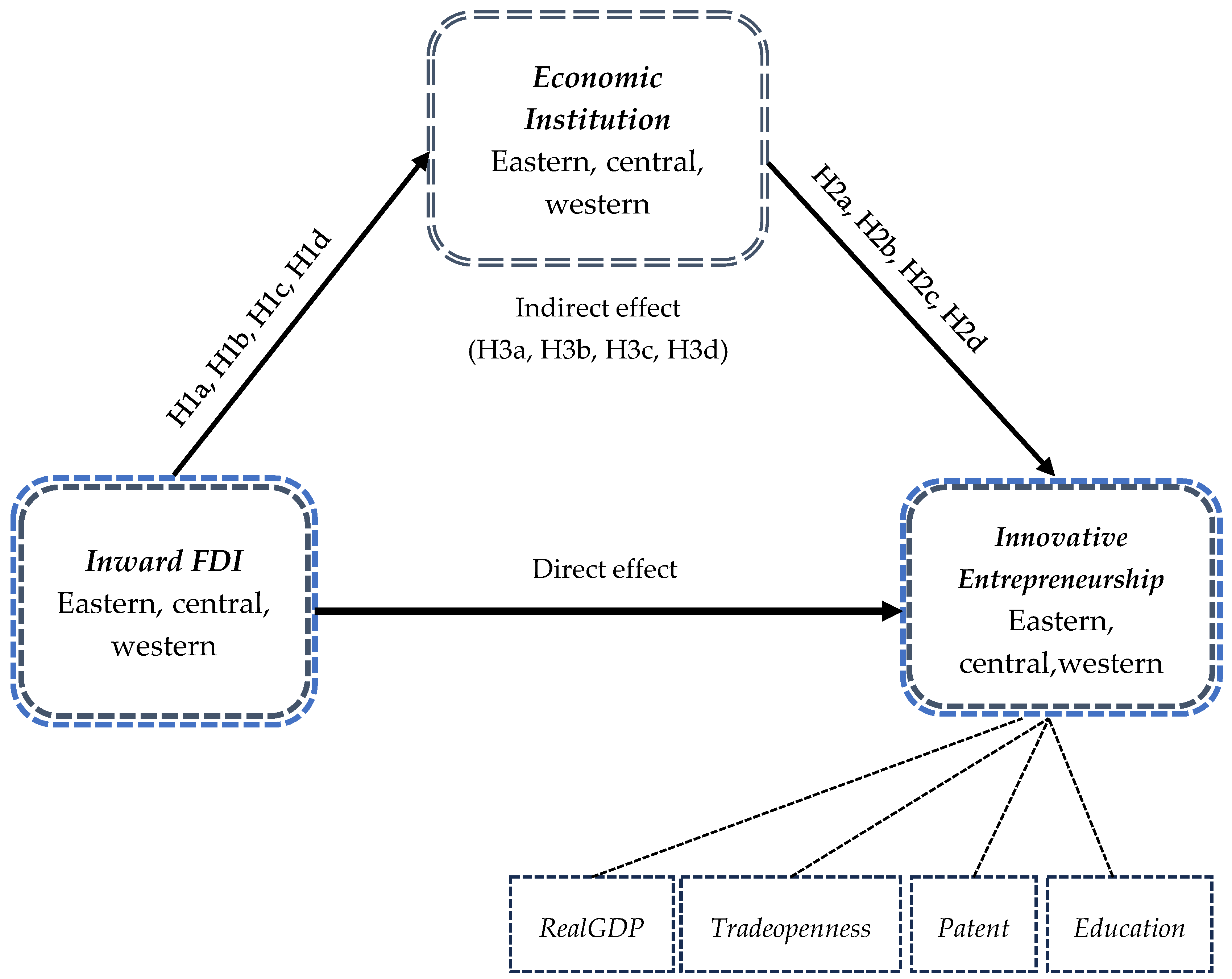

This study investigates the spillover effects of IFDI and the mediating role of marketization in the relationship between IFDI and innovative entrepreneurship in China.

Figure 1 illustrates the research model used in this study. To achieve our research objectives, we first have to prove the direct relationship between IFDI and innovative entrepreneurship to demonstrate the spillover effect. Second, we must verify whether IFDI influences the development of marketization, thus upgrading or diminishing the absorptive capacity of the institution. Third, we test whether marketization affects the development of innovative entrepreneurship. Finally, we identify the mediating role of marketization in the relationship between IFDI and innovative entrepreneurship. We also include the following control variables in our research model: real GDP, trade openness, patent rate, and education rate.

4. Emprical Results

Table 2 lists the descriptive statistical information for all variables in this study. The data for the three main variables show considerable regional differences. For example, innovative entrepreneurship ranges from a minimum level of 0.693 (Hainan Province in 2017) to a maximum level of 8.997 (Zhejiang Province in 2014), IFDI ranges from a minimum of 6.100 (Qinghai Province in 2018) to a maximum of 15.090 (Jiangsu Province in 2012), and the level of marketization ranges from a minimum of 3.360 (Xinjiang in 2012) to a high of 11.380 (Shanghai in 2018). Overall, the data show a decreasing pattern from eastern, to the central and western. The eastern region has more IFDI, a higher level of marketization, and more vigorous innovative entrepreneurial activities, while the western region has the least IFDI and a low level of marketization.

Table 3 summarizes the pairwise correlation matrix for all variables and the results of the multicollinearity test. The highly significant correlation of all variables at the 1% level suggests that there might be a problem of multicollinearity between the variables. However, our examination of multicollinearity indicates no such problem, as the range of VIF values from 1.92 to 6.28 does not exceed the generally accepted threshold of 10 [

65].

A three-step hierarchical regression analysis [

64] is used to test the mediating role of marketization in the relationship between IFDI and innovative entrepreneurship.

Table 4 and

Table 5 conclude the fixed-effects regression results of the mediating effect for China as a whole and for the subregions, respectively.

Table 6 and

Table 7 depict the fixed effects regression results with a one-year lag in IFDI as a robustness check.

In

Table 4, model (1) demonstrates that China’s overall IFDI positively and significantly affects innovative entrepreneurship at the 1% level, while model (2) shows that China’s overall IFDI does not have a significant spillover effect on the absorptive capacity of marketization.

Table 4 summarizes the results of the hierarchical regression of the mediating effects. Models (1) and (2) provide the necessary conditions to test the mediating role of marketization in model (3); however, the second step of the empirical results is not significant. Theoretically, in a three-step mediation analysis, the independent variable must significantly explain the change in the mediating variable [

64]. In our study, this step is not verified. In model (3), marketization has no significant effect on the development of innovative entrepreneurship, so it does not satisfy the mediation test. This means that marketization does not play a mediating role in the relationship between IFDI and innovative entrepreneurship development in China.

Models (4) to (6) in

Table 5 summarize the mediating regression results of marketization in the eastern region, where IFDI positively and significantly spillover both innovative entrepreneurship and marketization at the 5% and 10% levels, respectively. Second, in the mediation regression model (6), both IFDI and marketization positively affect innovative entrepreneurship at the 10% and 5% levels, indicating that marketization plays a partially mediating role in the relationship between IFDI and innovative entrepreneurship, with an indirect effect size of 0.053. Models (7) to (9) show the regression results for the mediating effect of marketization in the central region. IFDI only positively affects innovative entrepreneurship at the 1% significance level, but there is no significant spillover effect on marketization. In the third step of the mediation regression in model (9), marketization does not significantly promote innovative entrepreneurship, indicating that marketization has no mediating role in the central region. Models (10) to (12) list the results of the mediation regression of marketization in the western region. Unfortunately, we find that neither IFDI nor marketization has a positive and significant impact on the development of innovative entrepreneurship activities in the western region.

The use of a one-period lagged independent variable is a common and effective approach for robustness testing. This method addresses potential endogeneity issues, determines whether reverse causality exists, and captures the dynamic effects of economic development [

66]. Hence, in

Table 6 and

Table 7, we re-analyze the mediating role of marketization between IFDI and innovative entrepreneurship using IFDI lagged by one-period.

Table 6 reflects the mediating role of marketization in the relationship between IFDI and innovative entrepreneurship for China as a whole. The results are consistent with those in

Table 4, confirming that marketization does not play a mediating role in this relationship.

Table 7 displays the mediating role of marketization between IFDI and innovative entrepreneurship by subregion. The results are consistent with those in

Table 5, showing that in the eastern region, marketization plays a partial mediating role in the relationship between IFDI and innovative entrepreneurship. However, in the central and western regions, there is still no theoretical mediating effect between this relationship.

Table 6 and

Table 7 confirm the robustness and validity of the results, respectively.

5. Results Discussion

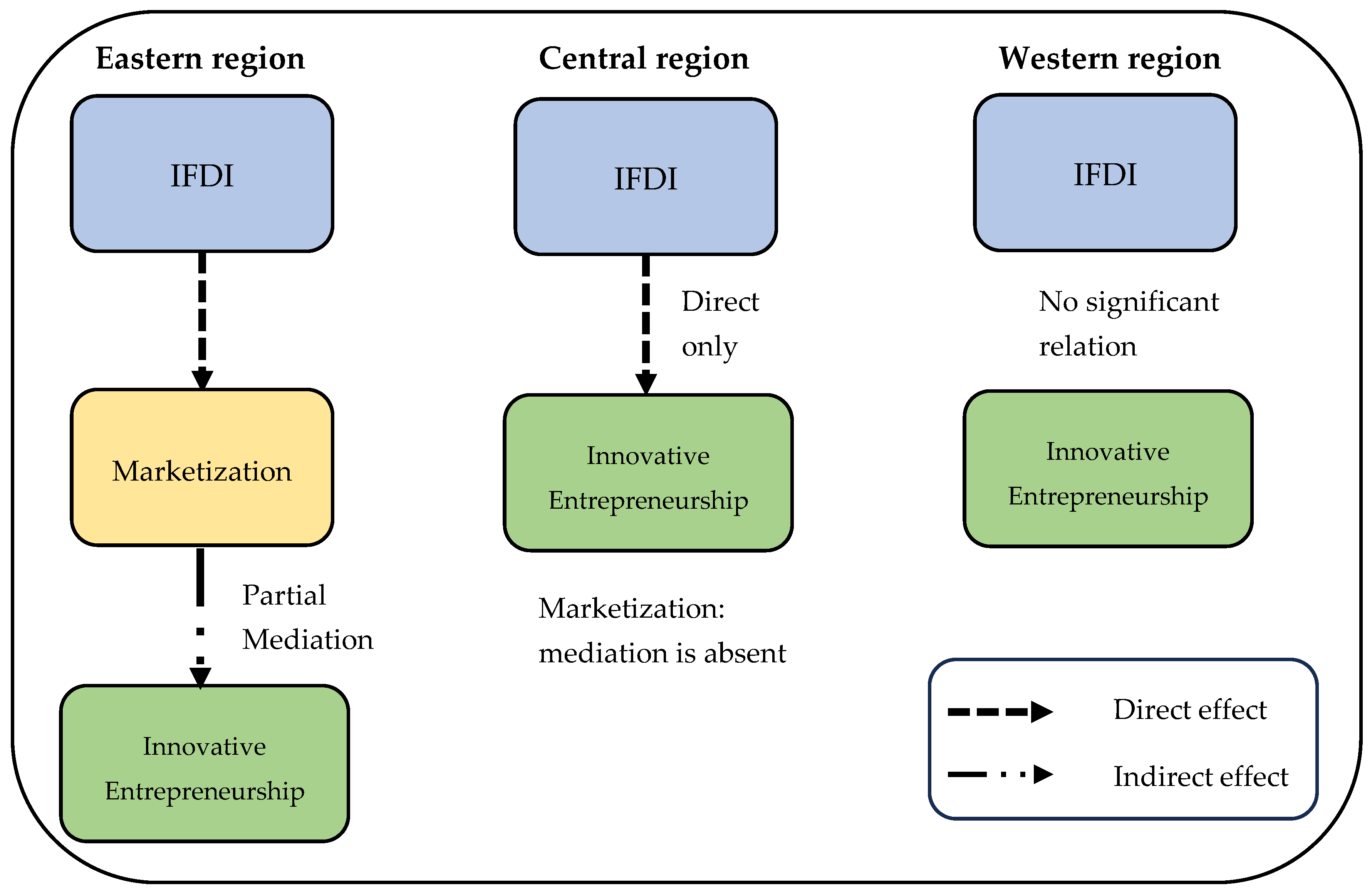

This study examines how IFDI influences innovative entrepreneurship in China through the lens of economic institutions, specifically focusing on “marketization” as a key mediating mechanism. Adopting a perspective of regional heterogeneity, the empirical findings reveal significant variations in the pathways through which IFDI affects marketization and innovative entrepreneurship across the eastern, central, and western regions. Notably, the mediating effect of marketization is statistically significant only in the eastern region, while it remains insignificant in the central and western regions (see

Figure 2). These results highlight the uneven distribution of institutional absorptive capacity across regions and underscore the critical role of institutional environments in enabling the effective spillover effects of IFDI.

In the eastern region, FDI has not only significantly promoted marketization but also effectively enhanced innovative entrepreneurship. More importantly, marketization plays a significant partial mediating role. This indicates that the marketization mechanism in the eastern region complements other institutional modules—such as the financial system, intellectual property protection, and legal environment—jointly fostering an institutional foundation conducive to innovative entrepreneurship. The region’s advanced venture capital ecosystem—which accounted for 72.3% of the national total in 2020—and mature technology transfer platforms (e.g., the Shanghai Intellectual Property Exchange) are highly aligned with the technological advantages of foreign capital, significantly strengthening the absorptive capacity of the marketization. At the same time, the weakening of administrative barriers has reduced institutional transaction costs and facilitated knowledge diffusion. Within this institutional context, marketization functions as an “absorptive container” that amplifies the positive externalities of IFDI, thereby stimulating entrepreneurial dynamism and innovation among private enterprises.

In contrast, the central region demonstrates a different pattern. While IFDI has a direct positive impact on innovative entrepreneurship, marketization does not exhibit a significant mediating effect. Although the average marketization index in central provinces has reached 5.8—comparable to the eastern region’s level in 2005—there remains a substantial gap between formal institutional arrangements and actual implementation. For instance, the registration rate of foreign technology contracts in the Hubei Free Trade Zone is only 32%, far below the eastern average of 68%, reflecting a degree of institutional decoupling. Moreover, the effect of IFDI in the central region appears to operate through informal networks, particularly government–business relations. Foreign firms often rely on local governments’ “ad hoc” policy support to access innovation-related resources, forming a substitute transmission mechanism. As a result, technology spillovers tend to rely more on human capital mobility than on institutional channels. These institutional frictions constrain the absorptive capacity of marketization and limit its ability to translate IFDI’s externalities into entrepreneurial outcomes. While the central region possesses the basic infrastructure for institutional absorption, it remains insufficient to activate a meaningful mediation mechanism.

In the western region, IFDI shows no significant impact on either marketization or innovative entrepreneurship, and the mediating role of marketization is absent. This outcome is closely tied to the region’s persistent institutional barriers. Administrative monopolies remain prevalent, particularly in resource-rich provinces such as Inner Mongolia and Qinghai, where key sectors like energy and mining are still dominated by state-owned enterprises. This has created a “glass door” effect—despite nominal liberalization, foreign technology often struggles to access the core innovation networks. Compared to the eastern region, the average adjudication time for intellectual property cases is much longer (287 days vs. 132 days), reflecting weaker protection of property rights and rule-of-law foundations. These institutional shortcomings make it difficult for foreign capital to establish sustainable innovation linkages. When the complexity of IFDI outpaces local institutional capacity, it can crowd out regional innovation inputs and lead to the brain-drain. In the absence of an effective institutional absorption path, the technological and managerial advantages brought by IFDI fail to translate into regional innovation capabilities, ultimately impeding the sustainable growth of entrepreneurial activity.

Building on an empirical analysis of regional heterogeneity in China, this study offers valuable insights for developing countries seeking to leverage IFDI to strengthen institutional development and foster innovative entrepreneurship. While the analysis is grounded in the Chinese context, the findings carry broader relevance, particularly for other developing economies undergoing institutional transitions. First, the results suggest that the positive externalities of IFDI—such as technology spillovers and managerial knowledge transfer—can only be effectively absorbed and translated into local entrepreneurial dynamism when a relatively mature institutional foundation is in place. This highlights the critical role of institutional absorptive capacity as a necessary condition for realizing the potential benefits of foreign capital. In its absence, IFDI may fail to deliver the anticipated outcomes. Second, regional variations in institutional environments shape the mechanisms through which IFDI influences local economic development. Thus, policy frameworks aimed at attracting IFDI in developing countries must go beyond the scale of capital inflows and focus more on the complementary development of institutional infrastructure. Breaking down institutional barriers and reducing institutional transaction costs are essential to moving from a strategy of merely “bringing in capital” to one of “bringing in knowledge” and “bringing in innovation”. Only through such coordinated reforms can sustainable innovation-driven growth be achieved.

6. Conclusions and Implications

6.1. Conclusions

This study investigates the mediating role of economic institutions (marketization) in the relationship between IFDI and innovative entrepreneurship in 30 provinces as well as three regions (eastern, central, and western) from 2010 to 2018. The empirical results provide partial support for the proposed hypotheses, specifically confirming H1b, H2b, and H3b. These findings indicate that marketization plays a critical mediating role in the eastern region, facilitating the positive effect of IFDI on innovative entrepreneurship.

Previous studies presented conflicting views on the impact of FDI and innovative entrepreneurship, ranging from positive to negative. This study introduces economic institutions as a critical mediator to reconcile these differences. We argue that spillovers from IFDI are the impetus for innovative entrepreneurship development in China, while the absorptive capacity of the economic institution is a pivotal bridge determining whether these spillovers are effectively released into regional innovative entrepreneurship. This study makes several contributions: first, it extends the traditional firm-level view of absorptive capacity to the institutional level and empirically confirms the mediating role of marketization in linking IFDI to regional innovative entrepreneurship. This offers a novel theoretical perspective on how IFDI indirectly fosters entrepreneurship through institutional channels. Second, this study constructs a bridge linking foreign capital inflows to innovative entrepreneurship, emphasizing the heterogeneous nature of this bridge across regions. This regional heterogeneity underscores the need for tailored policies that account for local institutional contexts to maximize the spillover effects of IFDI. Finally, by focusing on China—the world’s largest developing economy—this study not only informs pressing policy debates on how to better leverage IFDI for endogenous innovation but also offers valuable implications for other developing or emerging economies undergoing institutional transition.

6.2. Policy and Managerial Implications

To fully leverage the institutional dividends of IFDI, policymakers should adopt regionally differentiated strategies for sustainable development. In the eastern region, efforts should focus on deepening institutional openness and fostering a mutually reinforcing relationship between innovation and institutional development. This includes piloting participatory governance mechanisms for foreign firms. In addition, digital platforms for institutional iteration—such as a “real-time monitoring system for marketization” supported by blockchain—can be developed to identify mismatches between foreign technology demands and current regulatory frameworks. Cross-border intellectual property arbitration zones should also be piloted to reduce institutional transaction costs. In the central region, policy should focus on strengthening institutional enforcement to address the problem of “institutional decoupling”. This could involve the establishment of institutional performance evaluation centers to audit the actual implementation of market-oriented policies. Moreover, an “industry–institution matching fund” can be created to support institutional infrastructure tailored to industries concentrated in the region, ensuring better alignment between industrial needs and institutional infrastructure. In the western region, breaking out of the low-equilibrium trap requires investing in “institutional new infrastructure”. A dedicated “marketization capacity transfer payment” item should be included in central fiscal transfers, with disbursements linked to local institutional innovation performance (e.g., growth rate in technology contract registrations, efficiency in IP case adjudication). Furthermore, “lightweight” institutional infrastructure—such as fast-track IP service centers—should be prioritized in regions with relatively strong foundations.

For business managers, understanding regional variations in institutional environments is crucial for developing effective innovative entrepreneurship strategies. In the eastern region, firms can build institutional arbitrage capabilities by participating in standard-setting efforts, developing intermediary institutional services, and constructing resilient supply chains that are adaptive to regulatory changes. These strategies enable firms to gain a voice in rule-making and to capitalize on institutional advantages. In the central region, where institutional execution tends to lag and “institutional decoupling” is more common, firms may explore alternative transmission paths through informal institutional interfaces. This includes forming knowledge alliances with local governments, innovating technology transfer mechanisms (such as leveraging human capital advantages), and developing institution-avoidant technologies that navigate around institutional voids or inefficiencies. In the western region, firms should prioritize the development of localized technology adaptation teams to convert foreign advanced technologies into forms compatible with local institutional endowments. Additionally, they can work with local governments to establish “technology-institution integration” demonstration zones. Leveraging digital technologies to overcome institutional and geographic constraints can further support institutional applicability innovation, thereby enhancing localized absorptive capacity.

6.3. Limitations

Admittedly, there are some limitations in our study. For example, future research could determine where the threshold value of institutional absorptive capacity lies. Second, how do government institutions affect IFDI and the development of innovative entrepreneurship in a country, given that government institutions also play a significant role in the institutional environment. Finally, spillover effects may occur at the social, industrial, or individual level, so it is worthwhile to investigate whether research on the other two channels would yield different results. We hope that future studies can test and develop our theory on these bases to improve the generalizability of our findings.