1. Introduction

Household health is a critical global concern that directly affects quality of life and sustainable development. With the escalation of environmental pollution, health conditions such as respiratory, cardiovascular, and chronic diseases have become increasingly prevalent worldwide. Fine particulate matter (PM) and indoor air pollution are now recognized as major contributors to the global disease burden, resulting in millions of deaths annually [

1,

2,

3]. While developed countries face a rise in chronic illnesses associated with lifestyle factors [

4], developing regions, particularly China, are grappling with intensified exposure to environmental pollutants [

1,

5,

6]. In China, air pollution poses severe health risks, largely due to rapid industrialization and urbanization. High concentrations of sulfur dioxide (SO

2) and PM have made China one of the most polluted countries in the world in the past decades [

7], with urban residents and low-income groups disproportionately affected [

8,

9,

10].

Garbage sorting has emerged as a key strategy for improving environmental quality and promoting resource recycling. However, implementation differs significantly between the urban and rural regions. In 2019, the volume of domestic garbage generated in Chinese cities and towns reached 235 million tons, marking a 21.9% increase from 2018, and is projected to exceed 480 million tons by 2030 [

11]. In contrast, rural areas generate approximately 172 million tons of garbage annually, with an average daily per capita production of 0.8 kg [

12]. While the waste treatment rate in urban areas has surpassed 90%, it remains at approximately 50% in rural regions [

13].

Since 2019, the Chinese government has accelerated garbage sorting efforts, launching pilot programs in Shanghai and expanding mandatory sorting to 46 key cities [

14]. The 2020 policy framework aims to raise the recycling rate of bulk solid garbage to 60% by 2025, with a strong emphasis on resource utilization and environmental improvement [

15]. Prior studies show that garbage sorting improves recycling efficiency, reduces indoor air pollution, and enhances living conditions [

14,

16,

17]. However, its direct impact on household health remains insufficiently explored, underscoring the need for further research to better understand the potential role of garbage sorting in promoting public health and well-being.

This study systematically investigates the impact of garbage sorting on household health, addressing a critical yet underexplored area. Using data from the China Rural Revitalization Survey (CRRS), we quantitatively examine the correlation between garbage sorting and household health, as well as explore underlying mechanisms, such as the acquisition of health-related knowledge. The findings indicate a positive health impact, providing empirical support for more health-oriented garbage management policies. By integrating health considerations into environmental governance, this study contributes to sustained public engagement in garbage sorting and advances the broader goals of public health and ecological sustainability. Compared to the previous research, our study makes significant academic contributions in the following three key aspects:

- (1)

This study systematically examines the subjective health status of rural households in China using micro-level data, addressing a critical gap in the existing literature, which has largely overlooked this dimension in rural contexts. While prior studies have extensively explored the objective health status of households [

18,

19,

20], quantitative analyses of rural residents’ health perceptions remain scarce. By focusing specifically on rural households, this study provides a comprehensive assessment of the key determinants influencing subjective health and offers new empirical insights into the well-being of rural populations. The findings not only contribute to more effective policymaking in China but also offer a valuable reference for other countries, particularly developing nations, seeking to improve rural health outcomes and optimize public health policies.

- (2)

This study investigates the causal relationship between garbage sorting and household health, aiming to provide a comprehensive understanding of how garbage sorting influences health outcomes. Unlike previous studies that primarily focus on urban garbage sorting behavior or examine garbage sorting in limited contexts such as urban villages [

21], our study adopts a broader approach. By constructing a fixed effects model at the rural household level, we account for variations across provinces and villages, enabling a more accurate empirical analysis of the impact of garbage sorting on household health. Our findings indicate that garbage sorting in rural households significantly improves household health outcomes. In addition, we examine the role of household and social environmental factors in enhancing health, thereby deepening the understanding of key determinants and offering valuable insights for targeted policy interventions.

- (3)

This study aims to examine the heterogeneity in the effects of garbage sorting on household health and to explore its underlying mechanisms, an area that remains underexplored in the existing literature. The findings reveal considerable variations in the impact of garbage sorting on household health, influenced by regional and household characteristics. Specifically, while garbage sorting positively affects health across all regions, its impact is less pronounced in the central and western regions compared to the eastern region. Moreover, households with higher levels of education and income experience more substantial health benefits. Beyond these direct effects, garbage sorting also improved household health by enhancing the acquisition of health knowledge, which subsequently influences health-related behaviors. Identifying these disparities and underlying mechanisms is essential for optimizing garbage sorting policies and enhancing their effectiveness, particularly in reducing regional health inequalities and promoting the well-being of vulnerable populations.

The study is structured as follows:

Section 2 reviews the literature,

Section 3 outlines methods and data,

Section 4 presents results,

Section 5 provides a discussion, and

Section 6 concludes the study with policy implications.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Key Determinants of Household Garbage Sorting Behavior

The existing studies have identified a range of factors that influence household garbage sorting behavior, which can be broadly categorized into individual, household, environmental, and institutional dimensions. At the individual and household levels, women and households with higher levels of education are more likely to participate in garbage sorting activities, with education serving as a key driver of increased recycling rates [

22,

23]. Higher household income is also positively associated with a greater willingness to sort garbage [

24]. Household size plays a role as well, with smaller households generally exhibiting a stronger tendency to adopt sorting and recycling practices [

25]. Beyond household-level characteristics, environmental and institutional factors, such as community management, information dissemination, psychological drivers, and environmental regulations, also significantly influence garbage sorting behavior by shaping awareness, attitudes, and access to supporting resources [

11,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31].

2.2. Measurement and Determinants of Household Subjective Health

Subjective health is commonly conceptualized as an individual’s holistic perception and self-evaluation of their overall health status, encompassing both physical and psychological dimensions [

32]. Some studies have demonstrated that this self-reported indicator possesses considerable predictive validity, as it is significantly associated with future health risks, healthcare expenditures, and mortality rates [

33,

34]. Regarding its measurement, the academic community has largely converged on the use of hierarchical self-rating scales, in which individuals assess their perceived health status on an ordinal continuum, typically ranging from “very healthy” to “very unhealthy”. This approach enables the quantification of subjective health perceptions [

35,

36,

37,

38].

The existing studies have systematically examined the factors influencing subjective health from multiple dimensions. First, individual and household socioeconomic characteristics play a critical role. Education and income levels are widely recognized as key determinants of subjective health, typically exhibiting a significant positive correlation [

39]. Among the low-income households, improving energy efficiency has been shown to enhance household members’ health outcomes [

40]. Additionally, households using clean energy tend to report better health, with the likelihood of being healthy approximately 3.5% higher than that of households relying on traditional fuels [

37]. Second, lifestyle and health behaviors are also important contributors. Regular physical exercise significantly improves self-reported health status [

41], and individuals who actively engage with health-related topics are more likely to report better subjective health [

42]. Conversely, chronic pain is a major negative factor. Its adverse impact on subjective health is more pronounced among women than men, indicating a gender-based disparity [

43]. Third, both the physical and social environments influence subjective health. Factors such as housing quality and exposure to environmental pollution have been found to significantly affect individuals’ perceived health status [

44,

45].

2.3. Study on the Health Effects of Garbage Sorting Behavior

With growing recognition of the public health implications of environmental behavior, increasing scholarly attention has been directed toward the influence of practices such as garbage management and pollution control on population health. As a routine environmentally responsible activity, garbage sorting contributes to the improvement in residential living conditions and helps minimize exposure to harmful pollutants, thereby exerting a beneficial effect on individual health. Current research on the health impacts of garbage sorting behavior primarily focuses on two dimensions. On the one hand, inadequate disposal of household garbage poses significant health hazards. Several studies have highlighted that open dumping and the incineration of garbage release toxic emissions, which may lead to respiratory ailments, dermatological problems, and psychological distress [

46,

47,

48,

49], underscoring the adverse externalities of environmental pollution. On the other hand, the effective management of household garbage, particularly through garbage sorting and timely collection, can reduce the spread of infectious diseases and improve public satisfaction with environmental hygiene and overall quality of life [

14,

50].

2.4. Summary of Previous Research

The existing studies have provided valuable insights into the health implications of household garbage sorting, yet several limitations remain. First, while it is well established that garbage sorting significantly improves environmental quality, there is a notable lack of research focusing on its subjective health effects at the household level. Second, much of the existing literature is confined to urban contexts or relies on macro-level data, with limited empirical evidence derived from micro-level household data, particularly in rural areas. Third, the exploration of heterogeneity and the underlying mechanisms through which garbage sorting influences subjective health remains relatively underdeveloped. To address these gaps, this study utilizes micro-level survey data from rural households to systematically examine the impact of garbage sorting on subjective health outcomes. It further investigates potential heterogeneity across household characteristics and regions and explores the mechanisms through which garbage sorting affects household health.

3. Methods and Data

3.1. Model Specification

3.1.1. Fixed Effects Model

This study employs a fixed effects model to comprehensively analyze the impact of garbage sorting on household subjective health. This approach effectively controls for unobservable regional characteristics that may influence household health, thereby minimizing potential confounding effects and enabling a more accurate identification of the causal relationship between garbage sorting and health outcomes. By accounting for these unobserved regional characteristics, the model substantially reduces bias due to omitted variables, enhancing the robustness and reliability of the estimation results. The model is specified as follows:

where

represents the subjective health of the household;

denotes whether the household practices garbage sorting;

refers to a set of control variables, which include factors at both the household level and the economic environment level;

presents the regression coefficient associated with garbage sorting;

denotes the regression coefficients of the corresponding control variables;

and

represent fixed effects at the province and village levels, respectively;

is a constant term; and

is a random error term.

Household subjective health is significantly influenced by various household-level characteristics. Building on the substantial body of literature [

39,

40], this study identifies the following key variables:

Average household age (AGE): Determined based on the ages of all people living and eating in the household;

Average household education level (EDU): Determined based on the educational attainment of co-residing household members;

Household income level (INCOME): The household’s total annual income;

Household Internet use (INTERNET): Determined by whether the household uses a smartphone, tablet, or computer.

Understanding the economic environment of a region is essential for analyzing the subjective health of households within that area. Drawing on the existing literature [

44,

45], the following variables are selected to capture the key economic factors influencing household subjective health:

Clean water (CW): Determined by whether the household has access to clean water sources, such as tap water;

Social Capital (SC): Refers to the number of relatives or friends a household can turn to for financial assistance;

Infrastructure (INFRA): Indicates whether the household is satisfied with the current condition of village roads and household access roads;

Living Environment (ENV): Refers to the level of satisfaction with the household living environment.

3.1.2. Mediation Effect Model

To better understand how garbage sorting influences household subjective health, this study introduces health or wellness knowledge learning (KNOWLEDGE) as a mediating variable and employs a mediation effect model to analyze its potential mechanism. Household participation in garbage sorting can enhance environmental awareness, which in turn encourages household members to pay greater attention to and actively engage in learning health and wellness-related knowledge, ultimately fostering healthier lifestyles. The inclusion of this variable aims to uncover the indirect pathway through which garbage sorting impacts household health and to provide a foundation for more targeted and effective policy interventions. The model is specified as follows:

where

represents the mediating variable, namely health or wellness knowledge learning (KNOWLEDGE); and

, and

reflect the coefficients to be estimated in each model. The definitions of the remaining symbols are consistent with those provided in Formula (1).

3.2. Data Sources

Our study used data from the China Rural Revitalization Survey (CRRS) conducted by the Rural Development Institute, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, as our research sample. The CRRS is a nationally representative, long-term, and systematic rural survey project led by the Rural Development Institute. It primarily focuses on key issues related to rural transformation, household behavioral changes, and village governance under the framework of China’s Rural Revitalization Strategy. The survey data used in this study were collected between August and September 2020 across 10 provinces, including Guangdong, Zhejiang, Shandong, Anhui, Henan, Heilongjiang, Guizhou, Sichuan, Shaanxi, and Ningxia. It covered 50 counties and 156 townships, collecting data from 300 village questionnaires and over 3800 household questionnaires, encompassing information on more than 15,000 individuals.

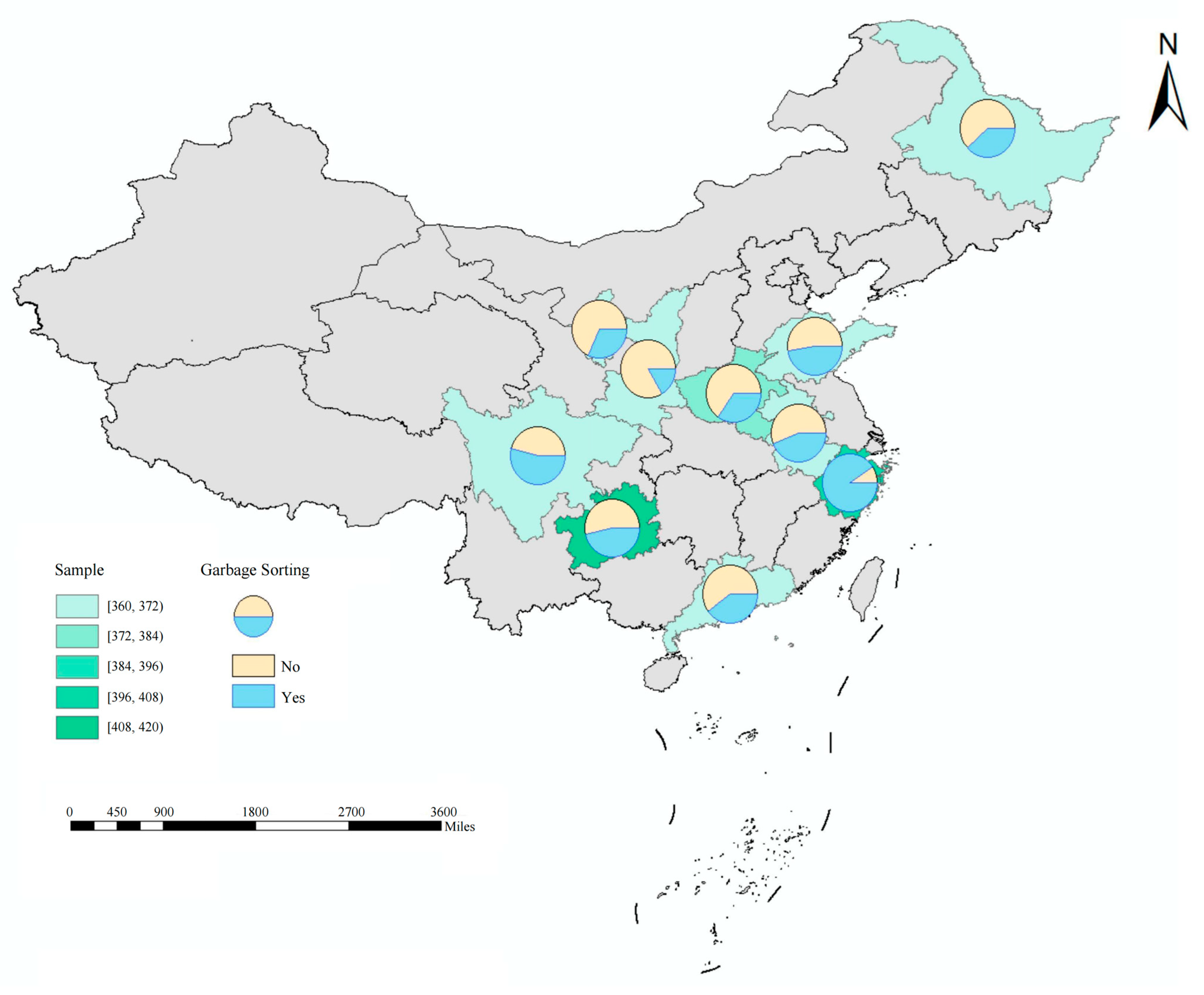

After data processing, the distribution of the samples included in this study is presented in

Figure 1. The number of sampled households and their respective participation rates in garbage sorting across each province are as follows: Heilongjiang surveyed 361 households, with 38.06% engaging in sorting; Zhejiang, with a sample of 400 households, exhibited a high participation rate of 90.75%; Anhui included 360 households, with 43.66% involved in sorting; Shandong’s sample of 364 households demonstrated a sorting rate of 47.53%; Henan surveyed 373 households, with 34.77% participating; Guangdong, comprising 361 households, showed a participation rate of 40.11%; Sichuan, with 363 households, had 53.72% practicing sorting; Guizhou surveyed 416 households, with a rate of 46.63%; Shaanxi included 362 households, with only 16.62% engaged in sorting; and Ningxia, with 370 households, recorded a participation rate of 32.16%. (For the garbage sorting conditions at the village level, see

Table S1 in the Supplementary Materials).

3.3. Descriptive Statistics of Variables

Household subjective health is measured as an ordered categorical variable ranging from 1 to 5, with higher values indicating poorer perceived health among household members. The garbage sorting variable is a binary indicator, taking the value of 1 if the household practices garbage sorting and 0 otherwise. In addition, this study introduces health and wellness knowledge learning as a mediating variable to explore the underlying mechanism through which garbage sorting influences household subjective health. To minimize the estimation bias caused by omitted variables, the analysis includes a set of household and economic characteristics as control variables. Descriptive statistics of the variables are presented in

Table 1.

4. Results

4.1. The Impact of Garbage Sorting on Household Subjective Health

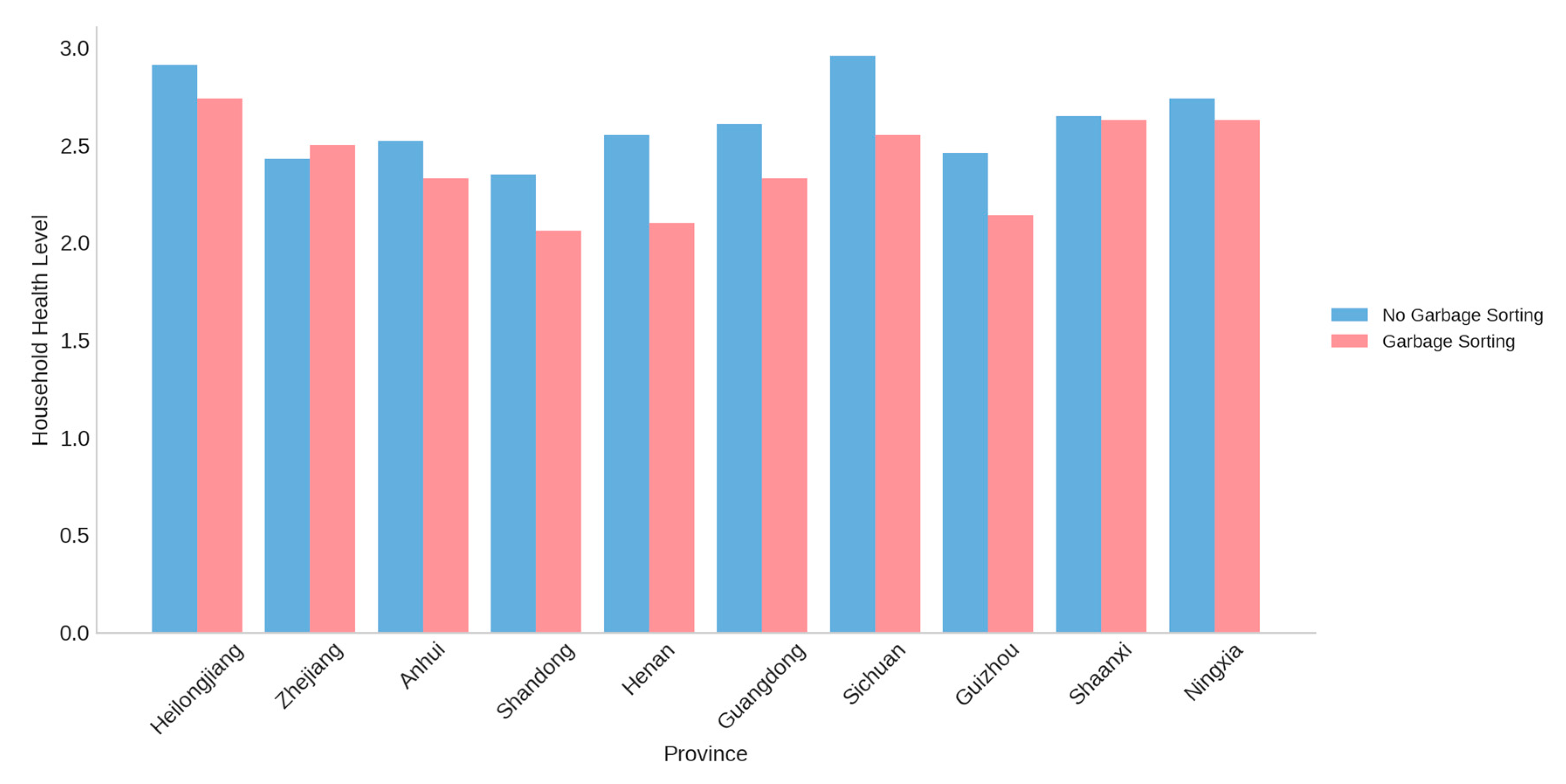

Figure 2 presents a comparison of household subjective health between households that practice garbage sorting and those that do not across the various provinces. As shown in the figure, households engaging in garbage sorting generally report better subjective health outcomes than those that do not. Among the 10 provinces analyzed, the differences are most pronounced in Henan and Sichuan. In Henan, the average subjective health score for households practicing garbage sorting is 2.10, compared to 2.55 for those that do not, a difference of 0.45. Similarly, in Sichuan, the scores are 2.55 for households that sort garbage and 2.96 for those that do not, reflecting a difference of 0.41. These results suggest that garbage sorting may contribute positively to the improvement in household members’ subjective health.

This study analyzes the impact of garbage sorting on household health, with the regression results presented in

Table 2. Column (1) reports the baseline regression without any control variables, while Column (2) adds a set of control variables but does not include fixed effects. Columns (3) and (4) further incorporate fixed effects at the province and village levels, in addition to the control variables. As shown in column (4), garbage sorting reduces subjective health scores by 0.16 units,

p < 0.01. Moreover, across all the other models, the coefficient for the garbage sorting variable remains negative and statistically significant at the 1% level (

p < 0.01), indicating that the results are both robust and consistent. This suggests that households engaging in garbage sorting generally exhibit better health. The observed effect may be attributed to the positive role of garbage sorting in enhancing the living environment and reducing exposure to air pollution [

51], thereby contributing to the overall improvement in household health.

The analysis of control variables reveals that the household’s average education level (EDU), income (INCOME), and social capital (SC) exhibit significant negative coefficients at the 10% (

p < 0.1), 1% (

p < 0.01), and 5% (

p < 0.05) significance levels, respectively. In contrast, the average age of household members (AGE) and the quality of the living environment (ENV) show significant positive effects, suggesting a detrimental impact on subjective health. These findings imply that higher levels of education, income, and social capital contribute to improved household health. Households with higher educational attainment tend to possess stronger health awareness and capacity for disease prevention [

52,

53], enabling them to adopt healthier lifestyles and make more informed health-related decisions. Higher household income enhances access to medical services, nutritious food, and better living conditions, all of which are conducive to health. Additionally, greater social capital, reflected in the ability to rely on relatives or friends for support, can help households better cope with financial or health-related stress, thereby improving overall well-being. On the other hand, an increase in the average age of household members is typically associated with greater health risks and a higher likelihood of chronic illness [

54]. Furthermore, poor living environments, often characterized by pollution and inadequate sanitation, increase exposure to health hazards, which can negatively affect a household’s subjective health status.

4.2. Robustness Test

To ensure the validity and robustness of the baseline regression results, this study used a variety of methods to re-estimate the model. In

Table 3, Column (1) presents the results of replacing the dependent variable with “changes in physical condition in the past year” to test consistency; Column (2) includes fixed effect interaction terms to assess the model’s robustness under more potential heterogeneity controls; Column (3) excludes the top 1% of households by income to eliminate the influence of outliers; Column (4) tests the robustness by replacing the sample source, using the health evaluation of the main respondent of the household to represent the overall situation of the household. The regression results consistently show that garbage sorting maintains a significant negative association with household subjective health at the 1% significance level (

p < 0.01), thereby confirming the robustness and reliability of the findings.

In addition, this study employed the propensity score matching (PSM) method to further test the robustness of the regression results. The outcomes are presented in

Table 4. Column (1) reports the results based on nearest neighbor matching with one neighbor (K = 1), while Column (2) presents the results using nearest neighbor matching with four neighbors (K = 4). Column (3) applies the radius caliper matching method (R = 0.01), and Column (4) uses kernel matching. As shown in

Table 4, the estimated coefficients across different matching methods remain highly consistent with the baseline regression results in both sign and statistical significance, with no substantial deviations observed. This consistency further reinforces the robustness and credibility of the study’s conclusions.

4.3. Heterogeneity Analysis

4.3.1. Regional Heterogeneity Analysis

Table 5 presents the results of the regional heterogeneity analysis, in which the sample is divided into the eastern region and the central and western regions based on household geographical location. The regression results in Columns (1) and (2) indicate that the impact of garbage sorting on household subjective health is significantly negative at the 5% level (

p < 0.05) in both regions, suggesting that garbage sorting generally contributes to improved household health. However, the coefficient in the eastern region is slightly larger than that in the central and western regions, implying a more pronounced health-promoting effect. This difference may be attributed to factors such as a more comprehensive garbage sorting system, higher levels of environmental and health awareness among residents, and more standardized sorting practices in the eastern region. For instance, among the sample households, the participation rate of rural households in garbage sorting in Zhejiang reaches as high as 90.75%, further highlighting the widespread adoption and effectiveness of garbage sorting in the eastern region. Similarly, Columns (3) and (4) compare the southern and northern regions. The impact coefficients for both regions are significantly negative at the 5% level (

p < 0.05), with no substantial difference observed between the two. This indicates that garbage sorting contributes to improved household health in both regions, and the magnitude of its effect does not differ significantly between the south and the north.

4.3.2. Household Heterogeneity Analysis

Table 6 presents the results of the household heterogeneity analysis, in which the sample is divided into high-education and low-education groups based on the average education level of the household. The regression results in Columns (1) and (2) show that the coefficients for the impact of garbage sorting on household health are significantly negative at the 1% level (

p < 0.01) for the high-education households and at the 10% level (

p < 0.1) for the low-education households. Moreover, the effect size is notably larger for the high-education households, indicating that although garbage sorting contributes to improved health in both groups, the health-promoting effect is more pronounced among the households with higher education levels. This may be explained by the fact that highly educated households typically possess stronger health awareness and greater environmental consciousness, which leads to a more standardized and effective implementation of garbage sorting and, consequently, greater health benefits [

52,

53]. In contrast, although the low-education households also experience positive effects, the limited health knowledge and potentially less consistent sorting practices may result in relatively smaller improvements in health.

Similarly, the sample households are divided into high-income and low-income groups based on the median income. The regression results in Columns (3) and (4) show that the coefficient for the impact of garbage sorting on the high-income households is significantly negative at the 1% level (p < 0.01), while the effect is not statistically significant for the low-income households. This indicates that garbage sorting contributes to improved health among the high-income households but has no significant effect on the health of the low-income households. A possible explanation is that the high-income households typically enjoy better living conditions and more complete sanitary facilities, which enable them to more fully realize the environmental and health benefits of garbage sorting. In contrast, the low-income households are constrained by limited infrastructure and resources, and even when they participate in garbage sorting, the health gains they experience tend to be relatively limited.

4.3.3. Mechanism Analysis

Building on the established relationship between garbage sorting and household health, this study further investigates the underlying mechanism through which this effect may occur. Specifically, we propose that the acquisition of health and wellness knowledge serves as a potential mediating variable in the relationship between garbage sorting and household health. The mediating effect is examined in detail. Column (1) of

Table 7 shows that garbage sorting significantly promotes the acquisition of health and wellness knowledge within households. Column (2) demonstrates that both garbage sorting and health knowledge acquisition have significant impacts on household health, suggesting that garbage sorting improves health partly by enhancing engagement with health and wellness knowledge. These findings confirm that health knowledge learning plays a partial mediating role in the relationship. A possible explanation is that garbage sorting behavior raises environmental awareness and health consciousness among household members, encouraging them to actively seek out relevant health knowledge, which in turn contributes to better household health.

4.3.4. Further Analysis

This study highlights the significant impact of garbage sorting on rural households’ health. Building on this foundation, it further explores whether garbage sorting also influences other household health behaviors. The results are presented in

Table 8. Column (1) shows that garbage sorting has a statistically significant positive effect on household sugar intake control at the 5% level (

p < 0.05), indicating that households engaging in garbage sorting are more likely to consciously regulate their sugar consumption. Columns (2), (3), and (4) demonstrate that garbage sorting also has a significant positive effect on salt intake control, oil intake control, and health product consumption at the 10% significance level (

p < 0.1). These findings suggest that garbage sorting not only encourages households to limit their intake of salt and oil but also promotes the consumption of health-related products. Overall, the results indicate that garbage sorting can enhance overall household health while positively influencing a broader range of health-related behaviors, including dietary choices and the use of wellness products.

5. Discussion

This study used CRRS data to evaluate the impact of garbage sorting on household health, taking into account household characteristics as well as economic and environmental factors. The results indicate that garbage sorting has a significant positive effect on household health, which is consistent with findings in the existing literature and supports the view that pro-environmental behaviors positively contribute to household well-being. Previous studies have demonstrated that improvements in the living environment can enhance household health [

44,

45], and that households using clean energy tend to report better health status [

37]. Building on these insights, this study focuses specifically on household garbage sorting as a common form of daily environmental behavior, thereby enriching the understanding of how such practices affect health. Moreover, in contrast to most existing studies that rely on urban samples or macro-level data [

21,

55], this study employed micro-level data from rural households, helping to fill the gap in empirical evidence related to rural populations and offering new perspectives on the health implications of environmental behavior in less-studied settings.

This study finds that the health benefits of garbage sorting are more pronounced among the high-education and high-income groups, while the effects on the low-income households are less evident. However, some existing studies have reported no significant correlation between education level and household garbage sorting behavior [

56], and others have suggested that the impact of environmental behavior may inadvertently marginalize certain groups, such as the low-income population [

57]. In addition to household-level differences, the regional heterogeneity analysis reveals that the health-promoting effect of garbage sorting is slightly stronger in eastern China than in the central and western regions. This may be attributed to better infrastructure and higher levels of health literacy in the eastern region. At the household level, differences in education and income may jointly explain the varying degrees of health benefits derived from garbage sorting. Despite these variations in findings, garbage sorting, as a routine environmental practice, demonstrates a degree of universality in its health effects. Therefore, greater attention should be directed toward promoting garbage sorting among rural households in underdeveloped areas to ensure that the associated health benefits are equitably shared across all segments of the population.

In addition, this study finds that garbage sorting can indirectly improve household health by promoting household members’ engagement in health and wellness knowledge acquisition. Furthermore, garbage sorting positively influences other health-related household behaviors, such as the regulation of sugar, salt, and oil intake, as well as the consumption of health-related products. While the existing studies have acknowledged the direct health benefits of garbage sorting, few have provided an in-depth analysis of its indirect role in shaping household health through behavioral pathways [

46,

48]. Moreover, some studies tend to view garbage sorting merely as an environmental practice, overlooking its subtle yet meaningful influence on the development of health-related behavioral habits [

14,

16,

17]. By confirming both the direct impact of garbage sorting on subjective health and its indirect effects through behavioral and cognitive mechanisms, this study contributes to a more comprehensive understanding of the relationship between environmental behavior and health. It also offers a behaviorally informed foundation for policy design and public health interventions.

Prior studies on urban garbage management in China suggest that solid garbage governance is closely shaped by government policies, economic and technological development, and structural industrial transformation. For example, the ongoing shift in China’s industrial structure has significantly altered the composition of industrial solid garbage generation and treatment. Urbanization has also contributed to a decline in household garbage generation per unit of GDP [

58]. In response, local governments in urban areas have adopted regulatory, technological, and programmatic approaches to improve garbage management systems [

59]. The annual growth rate of urban solid garbage is estimated at approximately 8–10%, with total volume expected to reach 323 million metric tons by 2030 [

60]. These findings underscore the importance of centralized planning and infrastructure investment in urban garbage governance.

In contrast to these urban-centered approaches, rural areas face a markedly different context. Garbage management in rural regions is often constrained by limited infrastructure, weaker regulatory enforcement, and lower public awareness. These differences highlight the unique policy needs of rural areas. Rural garbage governance may require greater emphasis on education, community engagement, and infrastructure support to ensure effective implementation. As this study shows, while garbage sorting in rural households positively affects health and health-related behaviors, the mechanisms and challenges differ significantly from those in urban environments. This contrast underscores the importance of context-specific policy design tailored to the rural setting.

6. Conclusions and Policy Implications

This study aimed to comprehensively examine the health effects of household garbage sorting in rural China and to evaluate the underlying mechanisms through which garbage sorting promotes household health. To achieve this, we employed a fixed effects model to empirically assess the impact of garbage sorting and its key influencing factors, using data from the 2020 China Rural Revitalization Survey (CRRS). Additionally, we investigated how various regional and household characteristics contribute to differences in the health effects of garbage sorting. Finally, a mediation effect model was applied to explore the potential pathways through which garbage sorting influences household health.

The results show that the implementation rate of garbage sorting among rural households in Zhejiang Province is the highest, reaching 90.75%. The empirical findings indicate that garbage sorting reduces the subjective health score of rural households by 0.16 units, suggesting a significant improvement in household health. The impact is more pronounced in the eastern region, as well as among households with higher education levels and incomes. In addition, garbage sorting indirectly promotes household health by increasing household engagement in health knowledge acquisition. It also encourages other health-related behaviors, such as regulating sugar, salt, and oil intake, and increasing the consumption of health-related products. These findings confirm that environmental practices like garbage sorting contribute to improved rural household health through both direct and indirect pathways.

Our findings have important implications for policymaking in China and other countries. First, we find that garbage sorting not only significantly promotes the subjective health of households but also contributes to the improvement in other health-related behaviors, with this effect varying significantly across regions and household types. In particular, garbage sorting indirectly enhances household health by encouraging the acquisition of health and wellness knowledge. Therefore, we recommend that the central government continue promoting the widespread adoption of garbage sorting across regions and households, with particular attention to increasing participation among the low-income and the low-education households to ensure equitable access to the associated health benefits. Second, in economically underdeveloped rural areas, priority should be given to strengthening policy support for garbage sorting, encouraging household participation, and improving health outcomes by enhancing the living environment. At the same time, efforts should be made to expand the dissemination of health and wellness knowledge in rural communities in order to raise health awareness and promote healthier behaviors. These coordinated efforts can help achieve the synergistic advancement of both garbage sorting and public health.

Author Contributions

J.Y.: Conceptualization, methodology, writing—review and editing. S.C.: Methodology, writing—review and editing. Z.W.: Writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Supported by the Beijing Municipal Natural Science Foundation (9244020), Hunan Provincial Department of Education Scientific Research Outstanding Youth Project (22B1061), and a Comprehensive Survey on Rural Revitalization and China Rural Revitalization Survey Database (GQDC2020017; GQDC2022020; 2024ZDDC001) that was funded by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Ali, M.U.; Yu, Y.; Yousaf, B.; Munir, M.A.M.; Ullah, S.; Zheng, C.; Kuang, X.; Wong, M. Health impacts of indoor air pollution from household solid fuel on children and women. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 416, 126127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotich, I.K.; Musyimi, P.K. Engineering, Indoor air pollution in Kenya. Aerosol Sci. Eng. 2024, 8, 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Jia, Y.; Sun, Z.; Su, J.; Liu, Q.S.; Zhou, Q.; Jiang, G. Environmental pollution, a hidden culprit for health issues. Eco-Environ. Health 2022, 1, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente-Suárez, V.J.; Beltrán-Velasco, A.I.; Redondo-Flórez, L.; Martín-Rodríguez, A.; Tornero-Aguilera, J.F. Global impacts of western diet and its effects on metabolism and health: A narrative review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alharthi, M.; Hanif, I.; Alamoudi, H. Impact of environmental pollution on human health and financial status of households in MENA countries: Future of using renewable energy to eliminate the environmental pollution. Renew. Energy 2022, 190, 338–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafree, S.R.; Bukhari, N.; Muzamill, A.; Tasneem, F.; Fischer, F. Digital health literacy intervention to support maternal, child and family health in primary healthcare settings of Pakistan during the age of coronavirus: Study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e045163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, G.; Su, B. The spatial impacts of air pollution and socio-economic status on public health: Empirical evidence from China. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2022, 83, 101167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; He, R. PM2.5 pollution and health expenditure: Time lag effect and spatial spillover effect. J. Saf. Environ. 2019, 1, 326–336. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, W.; Deng, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, H.; Huo, X. Does income inequality impair health? Evidence from rural China. Agriculture 2021, 11, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, E.; Zhu, M.; Lin, Y.; Xi, X. Multilevel medical insurance mitigate health cost inequality due to air pollution: Evidence from China. Int. J. Equity Health 2024, 23, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cudjoe, D.; Nketiah, E.; Obuobi, B.; Adjei, M.; Zhu, B.; Adu-Gyamfi, G. Predicting waste sorting intention of residents of Jiangsu Province, China. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 366, 132838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Nketiah, E.; Cai, X.; Obuobi, B.; Adu-Gyamfi, G.; Adjei, M. What establishes citizens’ household intention and behavior regarding municipal solid waste separation? A case study in Jiangsu province. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 423, 138642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yajuan, J.; Minjuan, Z. Impact of domestic waste pollution perception and social capital on the farming households’ sorting of waste: Based on the survey of 1374 farming households in Shaanxi Province. Resour. Sci. 2020, 42, 2370–2381. [Google Scholar]

- Govindan, K.; Zhuang, Y.; Chen, G. Analysis of factors influencing residents’ waste sorting behavior: A case study of Shanghai. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 349, 131126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yao, Y.; Zuo, J.; Li, J. Key policies to the development of construction and demolition waste recycling industry in China. Waste Manag. 2020, 108, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, H.; Wang, D.; Li, H. Waste sorting and its effects on carbon emission reduction: Evidence from China. Chin. J. Popul. Resour. Environ. 2020, 18, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Li, T.; Zhai, Q. Life cycle impact assessment of garbage-classification based municipal solid waste management systems: A comparative case study in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, L.; Du, M. How digital finance shapes residents’ health: Evidence from China. China Econ. Rev. 2024, 87, 102246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Yao, L.; Ye, C.; Li, Z.; Yuan, J.; Tang, K.; Qian, D. Can health service equity alleviate the health expenditure poverty of Chinese patients? Evidence from the CFPS and China health statistics yearbook. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhao, L.; Gao, L.; Pan, A.; Xue, H. Health policy and public health implications of obesity in China. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2021, 9, 446–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, X.; Zhang, X. How Waste Sorting Has Been Implemented in Urban Villages in China. A Co-Production Theory Perspective. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2024, 33, 2345–2357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deshpande, N.A.; Ramanathan, N.V.; Babu, N.K.; Deshpande, A.; Ramanathan, V.; Babu, K. Assessing the socioeconomic factors affecting household waste generation and recycling behavior in Chennai: A survey-based study. Int. J. Sci. Res. Arch. 2024, 11, 750–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, D.; Shi, L.; Huang, X.; Zhao, Z.; Zhou, B.; Bethel, B.J. Influencing factors on the household-waste-classification behavior of urban residents: A case study in Shanghai. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Xu, Q.; Shen, X.; Chen, B.; Esfahani, S.S. The mechanism of household waste sorting behaviour—A study of Jiaxing, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaqi, C.; Xiao, H.; Xiaoning, Z.; Mei, Q. Influence of social capital on rural household garbage sorting and recycling behavior: The moderating effect of class identity. Waste Manag. 2023, 158, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, P.; Li, W.; Yang, W. Adolescents’ social media use and their voluntary garbage sorting intention: A sequential mediation model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, R.; Lin, B. Are residents willing to pay for garbage recycling: Evidence from a survey in Chinese first-tier cities. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2022, 95, 106789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Chen, H. Exploring the effect of family life and neighbourhood on the willingness of household waste sorting. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, E.; Esfandiar, K.; Jie, F.; Brown, K.; Djajadikerta, H. Please sort out your rubbish! An integrated structural model approach to examine antecedents of residential households’ waste separation behaviour. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 355, 131789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.; Li, W.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y. Influence of institutional perception factors on household waste separation behaviour: Evidence from Ganzhou, China. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2024, 68, 1761–1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Shen, N.; Ying, H.; Wang, Q. Factor analysis and policy simulation of domestic waste classification behavior based on a multiagent study—Taking Shanghai’s garbage classification as an example. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2021, 89, 106598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, E.J.; Hyun, E.J. The impacts of pilates and yoga on health-promoting behaviors and subjective health status. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, W.; Kong, F.; Pan, H.; Luan, S.; Yang, S.; Chen, S. Superior predictive value of estimated pulse wave velocity for all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality risk in US general adults. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Yan, Y.; Guo, Z.; Hou, H.; Garcia, M.; Tan, X.; Anto, E.O.; Mahara, G.; Zheng, Y.; Li, B. All around suboptimal health—A joint position paper of the Suboptimal Health Study Consortium and European Association for Predictive, Preventive and Personalised Medicine. EPMA J. 2021, 12, 403–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvano, C.; Engelke, L.; Di Bella, J.; Kindermann, J.; Renneberg, B.; Winter, S.M. Families in the COVID-19 pandemic: Parental stress, parent mental health and the occurrence of adverse childhood experiences—Results of a representative survey in Germany. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2022, 31, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çelik Keçili, M.; Sezgin Kiroğlu, B.; Esen, E. Does where you live affect your health? Evidence from households in Türkiye. Rev. Reg. Res. 2025, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Yu, Y.; He, Q.; Xu, D.; Qi, Y.; Deng, X. Impact of clean energy use on the subjective health of household members: Empirical evidence from rural China. Energy 2023, 263, 126006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voukelatou, V.; Gabrielli, L.; Miliou, I.; Cresci, S.; Sharma, R.; Tesconi, M.; Pappalardo, L. Analytics, Measuring objective and subjective well-being: Dimensions and data sources. Int. J. Data Sci. Anal. 2021, 11, 279–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathentamo, Q.; Lawana, N.; Hlafa, B. Interrelationship between subjective wellbeing and health. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Symonds, P.; Verschoor, N.; Chalabi, Z.; Taylor, J.; Davies, M. Home energy efficiency and subjective health in greater London. J. Urban Health 2021, 98, 362–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Chen, J.-H.; Liu, X.-H.; Ren, S.Q. Can physical exercise improve the residents’ health? Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 707292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bechraki, E.; Kontogiannis, F.; Mavrikaki, E. Subjective health literacy skills among Greek secondary school students: Results from a national-wide survey. Health Promot. Int. 2024, 39, daae063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weraman, P.; Susanto, N.; Wahyuni, L.T.S.; Pranata, D.; Saddhono, K.; Dewi, K.A.K.; Kurniawati, K.L.; Hita, I.P.A.D.; Lestari, N.A.P.; Nizeyumukiza, E. Chronic Pain and Subjective Health in a Sample of Indonesian Adults: A Moderation of Gender. J. Popul. Soc. Stud. 2024, 32, 278–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotink, J.; Gadeyne, S. Perception of the Residential Living Environment: The Relationship Between Objective and Subjective Indicators of the Residential Living Environment and Health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, Y.; González, R.E. Objective and subjective measures of air pollution and self-rated health: The evidence from Chile. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2024, 97, 413–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabi, O.A.; Pasa, T.B.C.; Adebo, T.C. Environmental Contamination and Public Health Effects of Household Hazardous Waste. J. ISSN 2023, 2766, 2276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayeleru, O.O.; Modekwe, H.U.; Adefiranye, O.O.; Lolade, B.; Fafowora, M.A.O.; Nyam, T.T.; Adesiyan, I.A.; Apata, P. The environmental fate of E-waste. In Electronic Waste Management: Policies, Processes, Technologies, and Impact; Kumar, S., Kumar, V., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Oluwagbayide, S.D.; Abulude, F.O.; Akinnusotu, A.; Arifalo, K.M. The Relationship between Waste Management Practices and Human Health: New Perspective and Consequences. Indones. J. Innov. Appl. Sci. 2024, 4, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, G.; Izah, S.C.; Ibrahim, M. Air pollution in the Niger Delta region of Nigeria: Sources, health effects, and strategies for mitigation. J. Environ. Stud. 2023, 29, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yigci, D.; Bonventre, J.; Ozcan, A.; Tasoglu, S. Repurposing Sewage and Toilet Systems: Environmental, Public Health, and Person-Centered Healthcare Applications. Glob. Chall. 2024, 8, 2300358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Vatsa, P.; Ma, W. Small acts with big impacts: Does garbage classification improve subjective well-being in rural China? Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2023, 18, 1337–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fard, N.A.; Morales, G.D.F.; Mejova, Y.; Schifanella, R. On the interplay between educational attainment and nutrition: A spatially-aware perspective. EPJ Data Sci. 2021, 10, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingston, G.; Huntley, J.; Liu, K.Y.; Costafreda, S.G.; Selbæk, G.; Alladi, S.; Ames, D.; Banerjee, S.; Burns, A.; Brayne, C. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2024 report of the Lancet standing Commission. Lancet 2024, 404, 572–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Xu, X.; Zhang, M.; Hu, C.; Zhang, X.; Li, C.; Nie, S.; Huang, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Hou, F. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in China: Results from the sixth China chronic disease and risk factor surveillance. JAMA Intern. Med. 2023, 183, 298–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Oliva, P.; Zhang, P. Air Pollution and Mental Health: Evidence from China. AEA Pap. Proc. 2024, 114, 423–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadhullah, W.; Imran, N.I.N.; Ismail, S.N.S.; Jaafar, M.H.; Abdullah, H. Household solid waste management practices and perceptions among residents in the East Coast of Malaysia. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zheng, X.; Liu, W.; Ma, L. More habitual deviation alleviates the trade-offs between dietary health, environmental impacts, and economic cost. J. Ind. Ecol. 2025, 29, 503–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Xi, B.; Huang, C.; Li, J.; Tang, Z.; Li, W.; Ma, C.; Wu, W. Conservation; Recycling, Solid waste management in China: Policy and driving factors in 2004–2019. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 173, 105727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; de Jong, M.; Zisopoulos, F.; Hoppe, T. Introducing a classification framework to urban waste policy: Analysis of sixteen zero-waste cities in China. Waste Manag. 2023, 165, 94–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurniawan, T.A.; Liang, X.; O’Callaghan, E.; Goh, H.; Othman, M.H.D.; Avtar, R.; Kusworo, T.D. Transformation of solid waste management in China: Moving towards sustainability through digitalization-based circular economy. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).