Green Supply Chain Management, Business Performance, and Future Challenges: Evidence from Emerging Industrial Sector

Abstract

1. Introduction

- RQ1. What is the relationship between Green Supply Chain Management (GSCM) and Business Performance (BP)?

- RQ2. How do Lean Management (LM) and Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) mediate the relationship between Green Supply Chain Management (GSCM) and Business Performance (BP)?

2. Review of Literature

2.1. Green Supply Chain Management

2.2. Business Performance (BP)

2.3. Lean Management (LM)

2.3.1. Total Quality Management

2.3.2. Just in Time (JIT)

2.3.3. Total Productive Maintenance (TPM)

2.4. Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR)

2.4.1. Social Dimensions

2.4.2. Stakeholder Dimension

2.5. Theoretical Framework and Hypotheses Development

2.5.1. GSCM and BP

2.5.2. GSCM and LM

2.5.3. GSCM and CSR

2.5.4. LM and BP

2.5.5. CSR and BP

2.5.6. LM Mediates the Relationship Between GSCM and BP

2.5.7. CSR Mediates the Relationship Between GSCM and BP

3. Methods and Materials

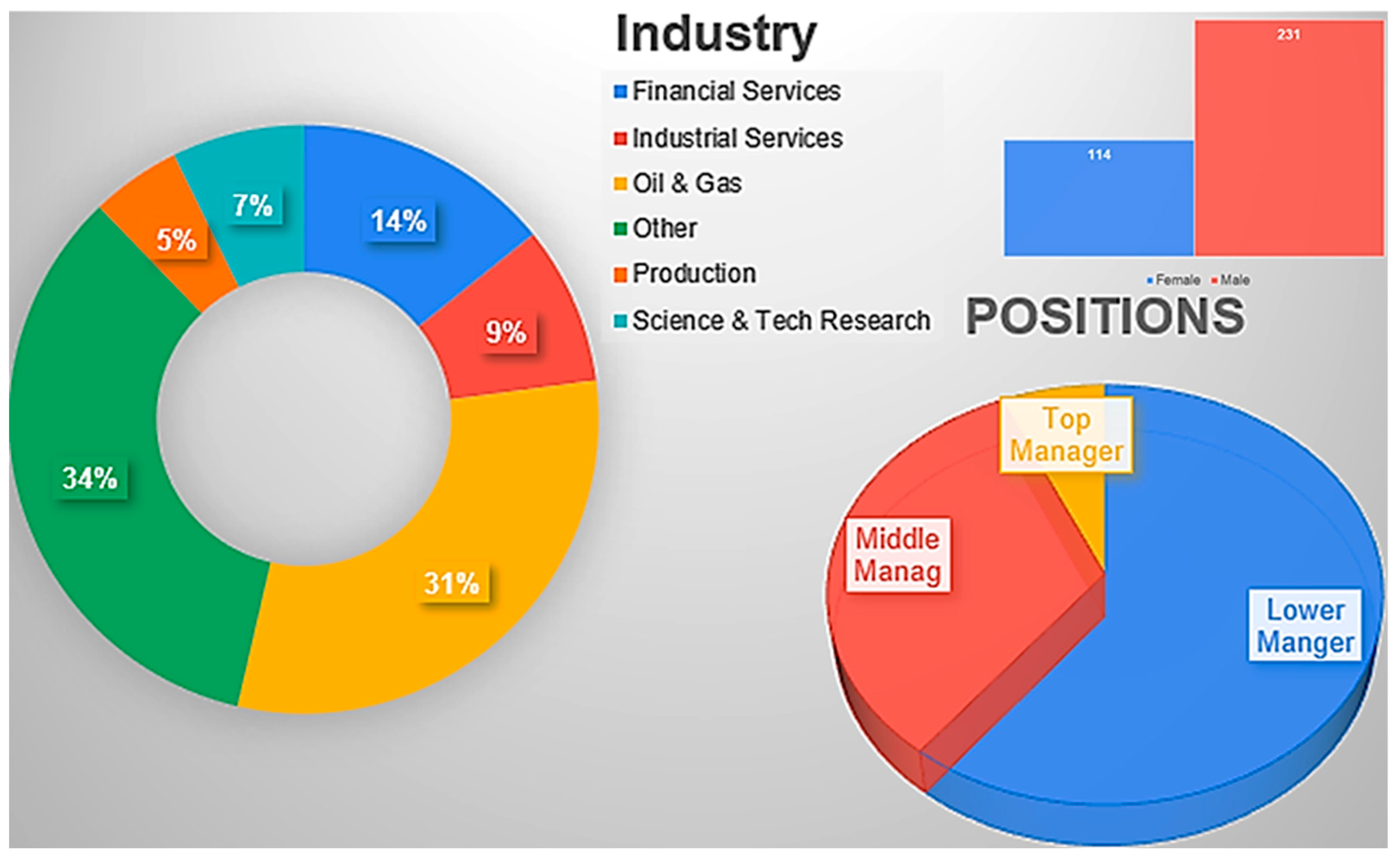

3.1. Data Collecting and Instruments

3.2. Data Analysis Procedure

4. Analysis and Results

4.1. Analysis of Results and Hypotheses Testing

4.2. Descriptive Statistics

4.3. Measurement Model Analysis

4.4. Hypotheses Testing Results

5. Discussion

Theoretical Implications

6. Conclusions

Managerial Relevance

7. Limitations and Scope for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. The Research Measurements

| Dimension | Variable | Code | Source(s) |

| Green Supply Chain Management |

| ED1 ED2 ED3 ED4 | [10,39,57] |

| GP1 GP2 GP3 GP4 | [10,39,57] | |

| IEM1 IEM2 IEM3 IEM4 | [39] | |

| Business Performance |

| MP1 MP2 MP3 MP4 | [217,218] |

| FP1 FP2 FP3 | [217,218] | |

| Lean management |

| TQM1 TQM2 TQM3 | [118,221] |

| JIT1 JIT2 JIT3 JIT4 | [118,196,205] | |

| TPM1 TPM2 TPM3 TPM4 | [116,117,118] | |

| Corporate Social Responsibility | Social Dimension & Stakeholder Dimension

| SD1 SD2 SD3 SD4 | [219,220] |

References

- Ministry of Industry and Mineral Resources. Initiatives. 2024. Available online: https://mim.gov.sa/en/initiatives/filter/7/ (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Alshehri, S.M.A.; Jun, W.X.; Shah, S.A.A.; Solangi, Y.A. Analysis of core risk factors and potential policy options for sustainable supply chain: An MCDM analysis of Saudi Arabia’s manufacturing industry. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 25360–25390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koberg, E.; Longoni, A. A systematic review of sustainable supply chain management in global supply chains. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 207, 1084–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, P.; Jha, A. Managing carbon footprint for a sustainable supply chain: A systematic literature review. Mod. Supply Chain. Res. Appl. 2020, 2, 123–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.W.; Hu, A.H. Green supply chain management in the electronic industry. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 5, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.K.; Kim, S.H.; Seo, M.K.; Hight, S.K. Market orientation and business performance: Evidence from franchising industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 44, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.J.; Tseng, M.L.; Vy, T. Evaluation the drivers of green supply chain management practices in uncertainty. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 25, 384–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, D.; Kwon, C. Structure of Green Supply Chain Management for Sustainability of Small and Medium Enterprises. Sustainability 2022, 14, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Sarkis, J.; Lai, K.H. Confirmation of a measurement model for green supply chain management practices implementation. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2008, 111, 261–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Sarkis, J.; Geng, Y. Green supply chain management in China: Pressures, practices and performance. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2005, 25, 449–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M. Sustainable supply chain management practices and operational performance. Am. J. Ind. Bus. Manag. 2013, 3, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Ikram, A.; Rehan, M.F.; Ahmad, A. Going green: Impact of green supply chain management practices on sustainability performance. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 973676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Chang, Y.T. Manufacturers’ closed-loop orientation for green supply chain management. Sustainability 2017, 9, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, F.; Iraldo, F. Shadows and lights of GSCM (Green Supply Chain Management): Determinants and effects of these practices based on a multi-national study. J. Clean. Prod. 2010, 18, 953–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diab, S.M.; Al-Bourini, F.A.; Abu-Rumman, A.H. The impact of green supply chain management practices on organizational performance: A study of Jordanian food industries. J. Manag. Sustain. 2015, 5, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nureen, N.; Liu, D.; Irfan, M.; Işik, C. Nexus between corporate social responsibility and firm performance: A green innovation and environmental sustainability paradigm. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 59349–59365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nureen, N.; Liu, D.; Irfan, M.; Malik, M.; Awan, U. Nexuses among green supply chain management, green human capital, managerial environmental knowledge, and firm performance: Evidence from a developing country. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gahlot, N.K.; Bagri, G.P.; Gulati, B.; Bhatia, L.; Das, S. Analysis of barriers to implement green supply chain management practices in Indian automotive industries with the help of ISM model. Mater. Today Proc. 2023, 82, 330–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajabion, L.; Khorraminia, M.; Andjomshoaa, A.; Ghafouri-Azar, M.; Molavi, H. A new model for assessing the impact of the urban intelligent transportation system, farmers’ knowledge and business processes on the success of green supply chain management system for urban distribution of agricultural products. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 50, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nureen, N.; Xin, Y.; Irfan, M.; Fahad, S. Going green: How do green supply chain management and green training influence firm performance? Evidence from a developing country. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 57448–57459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohno, T. Toyota Production System: Beyond Large-Scale Production; Productivity Press: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Adebayo, T.S. Environmental consequences of fossil fuel in Spain amidst renewable energy consumption: A new insights from the wavelet-based Granger causality approach. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2022, 29, 579–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Ajmal, M.M.; Jabeen, F.; Talwar, S.; Dhir, A. Green supply chain management in manufacturing firms: A resource-based viewpoint. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2023, 32, 1603–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J.B. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. In Economics Meets Sociology in Strategic Management; Emerald Group Publishing Limited.: Bingley, UK, 2000; pp. 203–227. [Google Scholar]

- Nureen, N.; Liu, D.; Irfan, M.; Sroufe, R. Greening the manufacturing firms: Do green supply chain management and organizational citizenship behavior influence firm performance? Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 77246–77261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Ren, L.; Yao, S.; Qiao, J.; Mikalauskiene, A.; Streimikis, J. Exploring the relationship between corporate social responsibility and firm competitiveness. Econ. Res.-Ekon. Istraz. 2020, 33, 1621–1646. [Google Scholar]

- Jaaffar, A.H.; Kaman, Z.K.; Razali, N.H.A.; Azmi, N.; Yahya, N.A. Employee’s past environmental related experience and green supply chain management practice: A study of Malaysian chemical related industries. In AIP Conference Proceedings; AIP Publishing: Melville, NY, USA, 2019; Volume 2124. [Google Scholar]

- Shibin, K.T.; Dubey, R.; Gunasekaran, A.; Hazen, B.; Roubaud, D.; Gupta, S.; Foropon, C. Examining sustainable supply chain management of SMEs using resource based view and institutional theory. Ann. Oper. Res. 2020, 290, 301–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moneva, J.M.; Ortas, E. Corporate environmental and financial performance: A multivariate approach. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2010, 110, 193–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iranmanesh, M.; Zailani, S.; Hyun, S.S.; Ali, M.H.; Kim, K. Impact of lean manufacturing practices on firms’ sustainable performance: Lean culture as a moderator. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awan, F.H.; Dunnan, L.; Jamil, K.; Atif, M.; Gul, R.F. Mediating role of green supply chain management between lean manufacturing practices and sustainable performance. Front. Psychol. 2022, 12, 810504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, B.; Gu, M.; Wang, Z. Green or lean? A supply chain approach to sustainable performance. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 216, 152–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinodh, S.; Ben Ruben, R.; Asokan, P. Life cycle assessment integrated value stream mapping framework to ensure sustainable manufacturing: A case study. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2016, 18, 279–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swenseth, S.R.; Olson, D.L. Trade-offs in lean vs. outsourced supply chains. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2016, 54, 4065–4080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Wang, X.; Luo, Y.; Yu, L.; Zhang, Z. Joint green marketing decision-making of green supply chain considering power structure and corporate social responsibility. Entropy 2021, 23, 564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andaregie, A.; Astatkie, T. Determinants of the adoption of green manufacturing practices by medium-and large-scale manufacturing industries in northern Ethiopia. Afr. J. Sci. Technol. Innov. Dev. 2022, 14, 960–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cockburn, I.M.; Henderson, R.M.; Stern, S. Untangling the origins of competitive advantage. Strateg. Manag. J. 2000, 21, 1123–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell’Atti, S.; Trotta, A.; Iannuzzi, A.P.; Demaria, F. Corporate social responsibility engagement as a determinant of bank reputation: An empirical analysis. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2017, 24, 589–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, S.; Bhattacharya, C.B.; Korschun, D. The role of corporate social responsibility in strengthening multiple stakeholder relationships: A field experiment. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2006, 34, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Sarkis, J.; Lai, K.H. Examining the effects of green supply chain management practices and their mediations on performance improvements. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2012, 50, 1377–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sousa Jabbour, A.B.L.; de Oliveira Frascareli, F.C.; Jabbour, C.J.C. Green supply chain management and firms’ performance: Understanding potential relationships and the role of green sourcing and some other green practices. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2015, 104, 366–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, A.B.; Al-Ghwayeen, W.S. Green supply chain management and business performance: The mediating roles of environmental and operational performances. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2020, 26, 489–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaggernath, R.; Khan, Z. Green supply chain management. World J. Entrep. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2015, 11, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahimnia, B.; Sarkis, J.; Davarzani, H. Green supply chain management: A review and bibliometric analysis. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2015, 162, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, M.L.; Islam, M.S.; Karia, N.; Fauzi, F.A.; Afrin, S. A literature review on green supply chain management: Trends and future challenges. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 141, 145–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S.K. Green supply-chain management: A state-of-the-art literature review. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2007, 9, 53–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Sarkis, J. The moderating effects of institutional pressures on emergent green supply chain practices and performance. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2007, 45, 4333–4355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.; Min, H. Measuring supply chain efficiency from a green perspective. Manag. Res. Rev. 2011, 34, 1169–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkis, J.; Zhu, Q.; Lai, K.H. An organizational theoretic review of green supply chain management literature. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2011, 130, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharfman, M.P.; Shaft, T.M.; Anex Jr, R.P. The road to cooperative supply-chain environmental management: Trust and uncertainty among pro-active firms. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2009, 18, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, H.; Galle, W.P. Green purchasing strategies: Trends and implications. Int. J. Purch. Mater. Manag. 1997, 33, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, P.R.; Poist, R.F. Green logistics strategies: An analysis of usage patterns. Transp. J. 2000, 40, 5–16. [Google Scholar]

- Young, A.; Kielkiewicz-Young, A. Sustainable supply network management. Corp. Environ. Strategy 2001, 8, 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, K.W.; Zelbst, P.J.; Meacham, J.; Bhadauria, V.S. Green supply chain management practices: Impact on performance. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2012, 17, 290–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkis, J. A strategic decision framework for green supply chain management. J. Clean. Prod. 2003, 11, 397–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perotti, S.; Zorzini, M.; Cagno, E.; Micheli, G.J. Green supply chain practices and company performance: The case of 3PLs in Italy. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2012, 42, 640–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Geng, Y.; Fujita, T.; Hashimoto, S. Green supply chain management in leading manufacturers: Case studies in Japanese large companies. Manag. Res. Rev. 2010, 33, 380–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younis, H.; Sundarakani, B.; Vel, P. The impact of implementing green supply chain management practices on corporate performance. Compet. Rev. 2016, 26, 216–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darnall, N.; Jolley, G.J.; Handfield, R. Environmental management systems and green supply chain management: Complements for sustainability? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2008, 17, 30–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosimato, S.; Troisi, O. Green supply chain management: Practices and tools for logistics competitiveness and sustainability. The DHL case study. TQM J. 2015, 27, 256–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Sarkis, J. Product eco-design practice in green supply chain management: A China-global examination of research. Nankai Bus. Rev. Int. 2021, 13, 124–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Feng, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Sarkis, J. Green supply chain management and the circular economy: Reviewing theory for advancement of both fields. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2018, 48, 794–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amemba, C.S.; Nyaboke, P.G.; Osoro, A.; Mburu, N. Elements of green supply chain management. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. 2013, 5, 51–61. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkis, J.; Bai, C.; Jabbour, A.B.L.D.S.; Jabbour, C.J.C.; Sobreiro, V.A. Connecting the pieces of the puzzle toward sustainable organizations: A framework integrating OM principles with GSCM. Benchmarking Int. J. 2016, 23, 1605–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eltayeb, T.K.; Zailani, S.; Ramayah, T. Green supply chain initiatives among certified companies in Malaysia and environmental sustainability: Investigating the outcomes. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2011, 55, 495–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preuss, L. In dirty chains? Purchasing and greener manufacturing. J. Bus. Ethics 2001, 34, 345–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusi-Sarpong, S.; Sarkis, J.; Wang, X. Assessing green supply chain practices in the Ghanaian mining industry: A framework and evaluation. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2016, 181, 325–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Wang, P.; Zhang, Y. Marketing and business performance of construction SMEs in China. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2007, 22, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, Q.; Isaac, D.; Dalton, P. The determinants of business performance of estate agency in England and Wales. Prop. Manag. 2008, 26, 255–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R.S.; Norton, D.P. The Strategy-Focused Organization: How Balanced Scorecard Companies Thrive in the New Business Environment; Harvard Business Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Panigyrakis, G.G.; Theodoridis, P.K. Internal marketing impact on business performance in a retail context. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2009, 37, 600–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, D.; Biswas, W. Articulating the value of human resource planning (HRP) activities in augmenting organizational performance toward a sustained competitive firm. J. Asia Bus. Stud. 2020, 14, 62–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popa, D.C.S.; Popa, D.N.; Bogdan, V.; Simut, R. Composite financial performance index prediction—A neural networks approach. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2021, 22, 277–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsaros, K.K.; Tsirikas, A.N.; Kosta, G.C. The impact of leadership on firm financial performance: The mediating role of employees’ readiness to change. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2020, 41, 333–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkandi, I.; Helmi, M. The impact of strategic agility on organizational performance: The mediating role of market orientation and innovation capabilities in emerging industrial sector. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2024, 11, 2396528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farris, P.W.; Bendle, N.; Pfeifer, P.; Reibstein, D. Marketing Metrics: The Definitive Guide to Measuring Marketing Performance; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Homburg, C.; Artz, M.; Wieseke, J. Marketing performance measurement systems: Does comprehensiveness really improve performance? J. Mark. 2012, 76, 56–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mintz, O.; Currim, I.S. What drives managerial use of marketing and financial metrics and does metric use affect performance of marketing-mix activities? J. Mark. 2013, 77, 17–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Womack, J.P.; Jones, D.T. Lean thinking—Banish waste and create wealth in your corporation. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 1997, 48, 1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, R.; Ward, P.T. Defining and developing measures of lean production. J. Oper. Manag. 2007, 25, 785–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeemah, A.J.; Wong, K.Y. Selection methods of lean management tools: A review. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2023, 72, 1077–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.M.; Murugesh, R.; Devadasan, S.R. Researches on lean manufacturing: Views from six perspectives. Int. J. Manag. Concepts Philos. 2018, 11, 132–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browning, T.R.; Heath, R.D. Reconceptualizing the effects of lean on production costs with evidence from the F-22 program. J. Oper. Manag. 2009, 27, 23–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiarini, A.; Baccarani, C.; Mascherpa, V. Lean production, Toyota Production System and Kaizen philosophy: A conceptual analysis from the perspective of Zen Buddhism. TQM J. 2018, 30, 425–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, A.B.; Alkhaldi, R.Z. Lean bundles in health care: A scoping review. J. Health Organ. Manag. 2019, 33, 488–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cua, K.O.; McKone, K.E.; Schroeder, R.G. Relationships between implementation of TQM, JIT, and TPM and manufacturing performance. J. Oper. Manag. 2001, 19, 675–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasdemir, C.; Gazo, R.; Quesada, H.J. Sustainability benchmarking tool (SBT): Theoretical and conceptual model proposition of a composite framework. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2020, 22, 6755–6797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Niu, Z.; Liu, C. Lean tools, knowledge management, and lean sustainability: The moderating effects of study conventions. Sustainability 2020, 12, 956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean Jr, J.W.; Bowen, D.E. Management theory and total quality: Improving research and practice through theory development. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1994, 19, 392–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, T.C. Total quality management as competitive advantage: A review and empirical study. Strateg. Manag. J. 1995, 16, 15–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toke, L.K.; Kalpande, S.D. Total quality management in small and medium enterprises: An overview in Indian context. Qual. Manag. J. 2020, 27, 159–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psomas, E.; Vouzas, F.; Kafetzopoulos, D. Quality management benefits through the “soft” and “hard” aspect of TQM in food companies. TQM J. 2014, 26, 431–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo-Mora, A.; Ruiz-Moreno, C.; Picón-Berjoyo, A.; Cauzo-Bottala, L. Mediation effect of TQM technical factors in excellence management systems. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 769–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakuan, N.M.; Yusof, S.M.; Laosirihongthong, T.; Shaharoun, A.M. Proposed relationship of TQM and organisational performance using structured equation modelling. Total Qual. Manag. 2010, 21, 185–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valmohammadi, C.; Roshanzamir, S. The guidelines of improvement: Relations among organizational culture, TQM and performance. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2015, 164, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.; Phan, C.A.; Matsui, Y. The impact of hard and soft quality management on quality and innovation performance: An empirical study. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2015, 162, 216–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, M.M.B.; Tari, J.J. The influence of soft and hard quality management practices on performance. Asia Pac. Manag. Rev. 2012, 17, 177. [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson, C.; Åhlström, P. Assessing changes towards lean production. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 1996, 16, 24–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, R.W. Attaining Manufacturing Excellence: Just in Time, Total Quality, Total People Involvement; The Dow Jones-Irwin/APICS Series in Production Management; Business One Irwin: Homewood, IL, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Furlan, A.; Dal Pont, G.; Vinelli, A. On the complementarity between internal and external just-in-time bundles to build and sustain high performance manufacturing. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2011, 133, 489–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackelprang, A.W.; Nair, A. Relationship between just-in-time manufacturing practices and performance: A meta-analytic investigation. J. Oper. Manag. 2010, 28, 283–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mistry, J.J. Origins of profitability through JIT processes in the supply chain. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2005, 105, 752–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaynak, H. The relationship between just-in-time purchasing techniques and firm performance. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2002, 49, 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakakibara, S.; Flynn, B.B.; Schroeder, R.G. A framework and measurement instrument for just-in-time manufacturing. Prod. Oper. Manag. 1993, 2, 177–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenny Koh, S.C.; Demirbag, M.; Bayraktar, E.; Tatoglu, E.; Zaim, S. The impact of supply chain management practices on performance of SMEs. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2007, 107, 103–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamming, R. Beyond Partnership—Strategies for Innovation and Lean Supply; Prentice-Hall: Hemel Hempstead, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Flynn, B.B.; Schroeder, R.G.; Sakakibara, S. The impact of quality management practices on performance and competitive advantage. Decis. Sci. 1995, 26, 659–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahuja, I.P.S.; Khamba, J.S. Total productive maintenance: Literature review and directions. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 2008, 25, 709–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, L. An information-processing model of maintenance management. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2003, 83, 45–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cholasuke, C.; Bhardwa, R.; Antony, J. The status of maintenance management in UK manufacturing organisations: Results from a pilot survey. J. Qual. Maint. Eng. 2004, 10, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamoun, F. Toward best maintenance practices in communications network management. Int. J. Netw. Manag. 2005, 15, 321–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modgil, S.; Sharma, S. Total productive maintenance, total quality management and operational performance: An empirical study of Indian pharmaceutical industry. J. Qual. Maint. Eng. 2016, 22, 353–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, A.H. Strategic dimensions of maintenance management. J. Qual. Maint. Eng. 2002, 8, 7–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhadury, B. Management of productivity through TPM. Productivity 2000, 41, 240–251. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, T.; Ali, S.M.; Allama, M.M.; Parvez, M.S. A total productive maintenance (TPM) approach to improve production efficiency and development of loss structure in a pharmaceutical industry. Glob. J. Manag. Bus. Res. 2010, 10, 186–190. [Google Scholar]

- Haddad, T.H.; Jaaron, A.A. The applicability of total productive maintenance for healthcare facilities: An implementation methodology. Int. J. Bus. Humanit. Technol. 2012, 2, 148–155. [Google Scholar]

- Alkhaldi, R.Z.; Abdallah, A.B. Lean management and operational performance in health care: Implications for business performance in private hospitals. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2020, 69, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguinis, H.; Glavas, A. What we know and don’t know about corporate social responsibility: A review and research agenda. J. Manag. 2012, 38, 932–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. A three-dimensional conceptual model of corporate performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1979, 4, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jnaneswar, K.; Ranjit, G. Effect of transformational leadership on job performance: Testing the mediating role of corporate social responsibility. J. Adv. Manag. Res. 2020, 17, 605–625. [Google Scholar]

- Matten, D.; Moon, J. Corporate social responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 2004, 54, 323–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, L.J. CSR and small business in a European policy context: The five “C” s of CSR and small business research agenda 2007. Bus. Soc. Rev. 2007, 112, 533–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, J.; de las Heras-Rosas, C. Corporate social responsibility and human resource management: Towards sustainable business organizations. Sustainability 2020, 12, 841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shams, S.M.R. Stakeholders’ perceptions and reputational antecedents: A review of stakeholder relationships, reputation and brand positioning. J. Adv. Manag. Res. 2015, 12, 314–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, N.K.; Nguyen, A.K.T.; Nguyen, T.T. Implementation of corporate social responsibility strategy to enhance firm reputation and competitive advantage. J. Compet. 2021, 13, 96–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marakova, V.; Wolak-Tuzimek, A.; Tuckova, Z. Corporate social responsibility as a source of competitive advantage in large enterprises. J. Compet. 2021, 13, 113–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, H.R. Social Responsibilities of the Businessman; University of Iowa Press: Iowa City, IA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Le, T.T. Corporate social responsibility and SMEs’ performance: Mediating role of corporate image, corporate reputation and customer loyalty. Int. J. Emerg. Mark. 2023, 18, 4565–4590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Ren, L.; Zhang, C.; Wang, C.; Ahmed, R.R.; Streimikis, J. Corporate social responsibility and employee behavior: Evidence from mediation and moderation analysis. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 1719–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crane, B. Revisiting who, when, and why stakeholders matter: Trust and stakeholder connectedness. Bus. Soc. 2020, 59, 263–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adib, M.; Zhang, X.; AAZaid, M.; Sahyouni, A. Management control system for corporate social responsibility implementation–a stakeholder perspective. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2021, 21, 410–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moure, R.C. CSR communication in Spanish quoted firms. Eur. Res. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2019, 25, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gras-Gil, E.; Manzano, M.P.; Fernández, J.H. Investigating the relationship between corporate social responsibility and earnings management: Evidence from Spain. BRQ Bus. Res. Q. 2016, 19, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, A.N.; Jeppesen, S. SMEs in their own right: The views of managers and workers in Vietnamese textiles, garment, and footwear companies. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 137, 589–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, D.; Lynch-Wood, G.; Ramsay, J. Drivers of environmental behaviour in manufacturing SMEs and the implications for CSR. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 67, 317–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobers, P.; Halme, M. Corporate social responsibility and developing countries. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2009, 16, 237–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, M.K. Influences of green supply chain management practices on organizational sustainable performance. Int. J. Environ. Monit. Prot. 2014, 1, 12–23. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, V.; Lenny Koh, S.C.; Baldwin, J.; Cucchiella, F. Natural resource based green supply chain management. Supply Chain. Manag. Int. J. 2012, 17, 54–67. [Google Scholar]

- Vachon, S.; Klassen, R.D. Environmental management and manufacturing performance: The role of collaboration in the supply chain. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2008, 111, 299–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, K.H.; Wong, C.W. Green logistics management and performance: Some empirical evidence from Chinese manufacturing exporters. Omega 2012, 40, 267–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, K.; Klingenberg, B.; Polito, T.; Geurts, T.G. Impact of environmental management system implementation on financial performance: A comparison of two corporate strategies. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2004, 15, 622–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.M.; Sung Rha, J.; Choi, D.; Noh, Y. Pressures affecting green supply chain performance. Manag. Decis. 2013, 51, 1753–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, N.A.H.N.; Yaakub, S. Reverse logistics: Pressure for adoption and the impact on firm’s performance. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2014, 15, 151. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, H.; Cruz-Machado, V. Integrating lean, agile, resilience and green paradigms in supply chain management (LARG_SCM). Supply Chain Manag. 2011, 2, 151–179. [Google Scholar]

- Mollenkopf, D.; Stolze, H.; Tate, W.L.; Ueltschy, M. Green, lean, and global supply chains. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2010, 40, 14–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Giovanni, P.; Cariola, A. Process innovation through industry 4.0 technologies, lean practices and green supply chains. Res. Transp. Econ. 2021, 90, 100869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dües, C.M.; Tan, K.H.; Lim, M. Green as the new Lean: How to use Lean practices as a catalyst to greening your supply chain. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 40, 93–100. [Google Scholar]

- Hallam, C.; Contreras, C. Integrating lean and green management. Manag. Decis. 2016, 54, 2157–2187. [Google Scholar]

- Alkandi, I.; Farooqi, M.R.; Hasan, A.; Khan, M.A. Green Products Buying Behaviour of Saudi Arabian and Indian Consumers: A Comparative Study. Int. J. Prof. Bus. Rev. 2023, 8, e03906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foo, P.Y.; Lee, V.H.; Tan, G.W.H.; Ooi, K.B. A gateway to realising sustainability performance via green supply chain management practices: A PLS–ANN approach. Expert Syst. Appl. 2018, 107, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, T.; Lai, L.; Le, T.; Tran, D. The impact of audit quality on performance of enterprises listed on Hanoi Stock Exchange. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2020, 10, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, O.; Rupp, D.E.; Farooq, M. The multiple pathways through which internal and external corporate social responsibility influence organizational identification and multifoci outcomes: The moderating role of cultural and social orientations. Acad. Manag. J. 2017, 60, 954–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Akremi, A.; Gond, J.P.; Swaen, V.; De Roeck, K.; Igalens, J. How do employees perceive corporate responsibility? Development and validation of a multidimensional corporate stakeholder responsibility scale. J. Manag. 2018, 44, 619–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tellis, G.J.; Prabhu, J.C.; Chandy, R.K. Radical innovation across nations: The preeminence of corporate culture. J. Mark. 2009, 73, 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, J. The relationship between sustainable supply chain management, stakeholder pressure and corporate sustainability performance. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 119, 317–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thong, K.C.; Wong, W.P. Pathways for sustainable supply chain performance—Evidence from a developing country, Malaysia. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swank, C.K. The lean service machine. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2003, 81, 123–130. [Google Scholar]

- Jaca, C.; Santos, J.; Errasti, A.; Viles, E. Lean thinking with improvement teams in retail distribution: A case study. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2012, 23, 449–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holweg, M. The genealogy of lean production. J. Oper. Manag. 2007, 25, 420–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callen, J.L.; Fader, C.; Krinsky, I. Just-in-time: A cross-sectional plant analysis. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2000, 63, 277–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fullerton, R.R.; McWatters, C.S.; Fawson, C. An examination of the relationships between JIT and financial performance. J. Oper. Manag. 2003, 21, 383–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Mehra, S.; Pletcher, M. The perceived impact of JIT implementation on firms’ financial/growth performance. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2004, 15, 118–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, R.; Linsmeier, T.J.; Venkatachalam, M. Financial benefits from JIT adoption: Effects of customer concentration and cost structure. Account. Rev. 1996, 71, 183–205. [Google Scholar]

- Tu, Q.; Vonderembse, M.A.; Ragu-Nathan, T.S.; Sharkey, T.W. Absorptive capacity: Enhancing the assimilation of time-based manufacturing practices. J. Oper. Manag. 2006, 24, 692–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konecny, P.A.; Thun, J.H. Do it separately or simultaneously—An empirical analysis of a conjoint implementation of TQM and TPM on plant performance. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2011, 133, 496–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Towill, D.; Christopher, M. The supply chain strategy conundrum: To be lean or agile or to be lean and agile? Int. J. Logist. 2002, 5, 299–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, R.; Ward, P.T. Lean manufacturing: Context, practice bundles, and performance. J. Oper. Manag. 2003, 21, 129–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, P.; Zhou, H. Impact of information technology integration and lean/just-in-time practices on lead-time performance. Decis. Sci. 2006, 37, 177–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackburn, J.D. Time-Based Competition: The Next Battleground in American Manufacturing; Business: Homewood, IL, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Kinney, M.R.; Wempe, W.F. Further evidence on the extent and origins of JIT’s profitability effects. Account. Rev. 2002, 77, 203–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopp, W.J.; Spearman, M.L. To pull or not to pull: What is the question? Manuf. Serv. Oper. Manag. 2004, 6, 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stump, B.; Badurdeen, F. Integrating lean and other strategies for mass customization manufacturing: A case study. J. Intell. Manuf. 2012, 23, 109–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeGroote, S.E.; Marx, T.G. The impact of IT on supply chain agility and firm performance: An empirical investigation. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2013, 33, 909–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tortorella, G.L.; Fettermann, D. Implementation of Industry 4.0 and lean production in Brazilian manufacturing companies. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2018, 56, 2975–2987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.H.; Yang, H.L.; Liou, D.Y. The impact of corporate social responsibility on financial performance: Evidence from business in Taiwan. Technol. Soc. 2009, 31, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeidi, S.P.; Sofian, S.; Saeidi, P.; Saeidi, S.P.; Saaeidi, S.A. How does corporate social responsibility contribute to firm financial performance? The mediating role of competitive advantage, reputation, and customer satisfaction. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uadiale, O.M.; Fagbemi, T.O. Corporate social responsibility and financial performance in developing economies: The Nigerian experience. J. Econ. Sustain. Dev. 2012, 3, 44–55. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, F.J.; Lin, C.W.; Chang, Y.N. The linkage between corporate social performance and corporate financial performance. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2010, 4, 406. [Google Scholar]

- Aupperle, K.E.; Carroll, A.B.; Hatfield, J.D. An empirical examination of the relationship between corporate social responsibility and profitability. Acad. Manag. J. 1985, 28, 446–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waddock, S.A.; Graves, S.B. The corporate social performance–financial performance link. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 303–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weshah, S.R.; Dahiyat, A.A.; Awwad, M.R.A.; Hajjat, E.S. The impact of adopting corporate social responsibility on corporate financial performance: Evidence from Jordanian banks. Interdiscip. J. Contemp. Res. Bus. 2012, 4, 34–44. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, M.L. Corporate social performance, corporate financial performance, and firm size: A meta-analysis. J. Am. Acad. Bus. 2006, 8, 163–171. [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers, W.; Choy, H.L.; Guiral, A. Do investors value a firm’s commitment to social activities? J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 114, 607–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallardo-Vázquez, D.; Sanchez-Hernandez, M.I. Measuring Corporate Social Responsibility for competitive success at a regional level. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 72, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, J.; Dawar, N. Corporate social responsibility and consumers’ attributions and brand evaluations in a product–harm crisis. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2004, 21, 203–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maignan, I.; Ferrell, O.C.; Hult, G.T.M. Corporate citizenship: Cultural antecedents and business benefits. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1999, 27, 455–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wayhan, V.B.; Balderson, E.L. TQM and financial performance: What has empirical research discovered? Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2007, 18, 403–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fullerton, R.R.; Wempe, W.F. Lean manufacturing, non-financial performance measures, and financial performance. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2009, 29, 214–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunnan, L.; Jamil, K.; Abrar, U.; Arain, B.; Guangyu, Q.; Awan, F.H. Analyzing the green technology market focus on environmental performance in Pakistan. In Proceedings of the 2020 3rd International Conference on Computing, Mathematics and Engineering Technologies (iCoMET), Sukkur, Pakistan, 29–30 January 2020; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Chronéer, D.; Wallström, P. Exploring waste and value in a lean context. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2016, 11, 282–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Viles, E.; Santos, J.; Muñoz-Villamizar, A.; Grau, P.; Fernández-Arévalo, T. Lean–green improvement opportunities for sustainable manufacturing using water telemetry in agri-food industry. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikumapayi, O.M.; Akinlabi, E.T.; Mwema, F.M.; Ogbonna, O.S. Six sigma versus lean manufacturing—An overview. Mater. Today Proc. 2020, 26, 3275–3281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, P.; Sadeghi, J.K.; Eseonu, C. A sustainable lean production framework with a case implementation: Practice-based view theory. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 277, 123078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghobakhloo, M.; Hong, T.S. IT investments and business performance improvement: The mediating role of lean manufacturing implementation. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2014, 52, 5367–5384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, A.; Lenox, M. Exploring the locus of profitable pollution reduction. Manag. Sci. 2002, 48, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.G.M.; Hong, P.; Modi, S.B. Impact of lean manufacturing and environmental management on business performance: An empirical study of manufacturing firms. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2011, 129, 251–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, S.; Wei, D.; Zhu, Y.G. An inventory of trace element inputs to agricultural soils in China. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 90, 2524–2530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campos, L.M.; Vazquez-Brust, D.A. Lean and green synergies in supply chain management. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2016, 21, 627–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, H.; Azevedo, S.G.; Cruz-Machado, V. Supply chain performance management: Lean and green paradigms. Int. J. Bus. Perform. Supply Chain Model. 2010, 2, 304–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engin, B.E.; Martens, M.; Paksoy, T. Lean and green supply chain management: A comprehensive review. In Lean and Green Supply Chain Management: Optimization Models and Algorithms; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Govindan, K.; Azevedo, S.G.; Carvalho, H.; Cruz-Machado, V. Lean, green and resilient practices influence on supply chain performance: Interpretive structural modeling approach. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 12, 15–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.; Raut, R.D.; Mangla, S.K.; Narkhede, B.E.; Luthra, S.; Gokhale, R. A systematic literature review to integrate lean, agile, resilient, green and sustainable paradigms in the supply chain management. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2021, 30, 1191–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Singh, H.; Kumar, A. Impact of lean practices on organizational sustainability through green supply chain management–an empirical investigation. Int. J. Lean Six Sigma 2020, 11, 1035–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Subramanian, N.; Abdulrahman, M.D.; Liu, C.; Lai, K.H.; Pawar, K.S. The impact of integrated practices of lean, green, and social management systems on firm sustainability performance—Evidence from Chinese fashion auto-parts suppliers. Sustainability 2015, 7, 3838–3858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, S.G.; Carvalho, H.; Duarte, S.; Cruz-Machado, V. Influence of green and lean upstream supply chain management practices on business sustainability. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2012, 59, 753–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarfraz, M.; Mohsin, M.; Naseem, S.; Kumar, A. Modeling the relationship between carbon emissions and environmental sustainability during COVID-19: A new evidence from asymmetric ARDL cointegration approach. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 16208–16226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, E. A review of corporate social responsibility in developed and developing nations. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 712–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getele, G.K.; Li, T.; Arrive, T.J. Corporate culture in small and medium enterprises: Application of corporate social responsibility theory. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 897–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ağan, Y.; Kuzey, C.; Acar, M.F.; Açıkgöz, A. The relationships between corporate social responsibility, environmental supplier development, and firm performance. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 1872–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, R.A.; Park, B.; Chang, B.Y. Corporate Social Responsibility Impact on Business Performance through Green Supply Chain Management: Evidence from Guatemala. Int. J. Internet Broadcast. Commun. 2019, 11, 59–64. [Google Scholar]

- Channa, N.A.; Hussain, T.; Casali, G.L.; Dakhan, S.A.; Aisha, R. Promoting environmental performance through corporate social responsibility in controversial industry sectors. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 23273–23286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, W. Corporate social responsibility, Green supply chain management and firm performance: The moderating role of big-data analytics capability. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2020, 37, 100557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Yang, S.; Shi, X. How corporate social responsibility and external stakeholder concerns affect green supply chain cooperation among manufacturers: An interpretive structural modeling analysis. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvia, A.L.; Leal Filho, W.; Brandli, L.L.; Griebeler, J.S. Assessing research trends related to Sustainable Development Goals: Local and global issues. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 208, 841–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooley, G.J.; Greenley, G.E.; Cadogan, J.W.; Fahy, J. The performance impact of marketing resources. J. Bus. Res. 2005, 58, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, A.; Bartle, C.; Stockport, G.; Smith, B.; Klobas, J.E.; Sohal, A. Business leaders’ views on the importance of strategic and dynamic capabilities for successful financial and non-financial business performance. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2015, 64, 908–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahta, D.; Yun, J.; Islam, M.R.; Bikanyi, K.J. How does CSR enhance the financial performance of SMEs? The mediating role of firm reputation. Econ. Res.-Ekon. Istraž. 2021, 34, 1428–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Servera-Francés, D.; Piqueras-Tomás, L. The effects of corporate social responsibility on consumer loyalty through consumer perceived value. Econ. Res.-Ekon. Istraž. 2019, 32, 66–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hyari, K.; Abu Hammour, S.; Abu Zaid, M.K.S.; Haffar, M. The impact of Lean bundles on hospital performance: Does size matter? Int. J. Health Care Qual. Assur. 2016, 29, 877–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Gabriel, M.; Patel, V. AMOS covariance-based structural equation modeling (CB-SEM): Guidelines on its application as a marketing research tool. Braz. J. Mark. 2014, 13, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: Areview and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamantopoulos, A.; Siguaw, J.A. Introducing LISREL: A Guide for Structural Equation Modelling; Sage Publications Ltd.: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 2000; pp. 1–192. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J.C.; Bernstein, I.H. The Assessment of Reliability. Psychom. Theory 1994, 3, 248–292. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, S.L. A natural-resource-based view of the firm. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 986–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yan, D. Exploration on the mechanism of the impact of green supply chain management on enterprise sustainable development performance. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Cronbach’s α | CR | AVE | Std. Factor Loading |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Green Supply Chain Management | 0.95 | 0.966 | 0.903 | |

| Eco-Design | 0.812–0.849 | |||

| Eco.1–Eco.4 | ||||

| Green Purchasing | 0.825–0.859 | |||

| GP.1–GP.4 | ||||

| Internal Environmental Management | 0.798–0.859 | |||

| IEM.1–IEM.4 | ||||

| Lean Management | 0.94 | 0.973 | 0.922 | |

| Total Quality Management | 0.79–0.834 | |||

| TQM.1–TQM.3 | ||||

| Just in Time | 0.749–0.831 | |||

| JT.1–JT.4 | ||||

| Total Productive Maintenance | 0.834–0.863 | |||

| TPM.1–TPM.4 | ||||

| Business Performance | 0.93 | 0.973 | 0.947 | |

| Marketing Performance | 0.829–0.883 | |||

| MP.1–MP.4 | ||||

| Financial Performance | 0.835–0.870 | |||

| FP.1–FP.3 | ||||

| Corporate Social Responsibility | 0.89 | 0.905 | 0.705 | |

| Social and Stakeholder Dimensions | 0.816–0.853 | |||

| CSR.1–CSR.4 | ||||

| GOFI | GOFI Criteria | Results | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| RMSEA | ≤0.08 | 0.058 | Good fit |

| TLI | ≥0.90 | 0.941 | Good fit |

| CFI | ≥0.90 | 0.946 | Good fit |

| GFI | ≥0.90 | 0.901 | Good fit |

| RMR | ≤0.08 | 0.031 | Good fit |

| Observed Variables | Direct Effect | Indirect Effect | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| GSCM → Bus. Perf. | 0.424 | - | 0.000 |

| GSCM → Lean Mgt. | 0.809 | - | 0.000 |

| GSCM → CSR | 0.891 | - | 0.000 |

| Lean Mgt. → Bus. Perf. | 0.407 | - | 0.000 |

| CSR → Bus. Perf. | 0.100 | - | 0.175 |

| GSCM → CSR → Bus. Perf. | - | 0.089 | 0.568 |

| GSCM → Lean Mgt. → Bus. Perf. | - | 0.329 | 0.028 |

| Hypothesis | Path | Beta (β) | p-Value | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HI | GSCM positively impacts BP | 0.424 | <0.001 | Supported |

| H2 | GSCM positively impacts LM | 0.809 | <0.001 | Supported |

| H3 | GSCM positively impacts CSR | 0.891 | <0.001 | Supported |

| H4 | LM positively impacts BP | 0.407 | <0.001 | Supported |

| H5 | CSR positively impacts BP | 0.10 | 0.175 | Not Supported |

| H6 | GSCM impacts BP via CSR | 0.089 | 0.568 | Not Supported |

| H7 | GSCM impacts BP via LM | 0.329 | 0.028 | Supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alkandi, I.; Alhajri, N.; Alnajim, A. Green Supply Chain Management, Business Performance, and Future Challenges: Evidence from Emerging Industrial Sector. Sustainability 2025, 17, 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17010029

Alkandi I, Alhajri N, Alnajim A. Green Supply Chain Management, Business Performance, and Future Challenges: Evidence from Emerging Industrial Sector. Sustainability. 2025; 17(1):29. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17010029

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlkandi, Ibrahim, Nouf Alhajri, and Abdulrhman Alnajim. 2025. "Green Supply Chain Management, Business Performance, and Future Challenges: Evidence from Emerging Industrial Sector" Sustainability 17, no. 1: 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17010029

APA StyleAlkandi, I., Alhajri, N., & Alnajim, A. (2025). Green Supply Chain Management, Business Performance, and Future Challenges: Evidence from Emerging Industrial Sector. Sustainability, 17(1), 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17010029