Spatiotemporal Evolution Characteristics and Causative Analysis of Toponymic Cultural Landscapes in Traditional Villages in Northern Guangdong, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

- The systematic organization and classification of traditional village toponyms in northern Guangdong based on the characteristics of place name cultural landscapes, used to reveal the spatial distribution pattern of place name cultural landscapes in the region.

- The analysis of the formation mechanisms of place name cultural landscapes in northern Guangdong, used to explain how natural and human geographical features influence the composition of traditional village toponyms.

- The interpretation of the overall spatial characteristics of traditional villages and their comprehensive influencing factors from the perspective of cultural ecology, used to propose rational protection and development strategies aimed at preserving the value of place name cultural heritage to the greatest extent possible.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources

2.2. Data Source

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. Kernel Density Estimation

2.3.2. Average Nearest Neighbor Index

2.3.3. Multiple Ring Buffer Analysis

2.3.4. Standard Deviation Ellipse Analysis Method

3. Results

3.1. Statistics of Traditional Village Toponyms and Landscape Types

3.1.1. Natural Toponymic Landscape

3.1.2. Cultural Toponymic Landscape

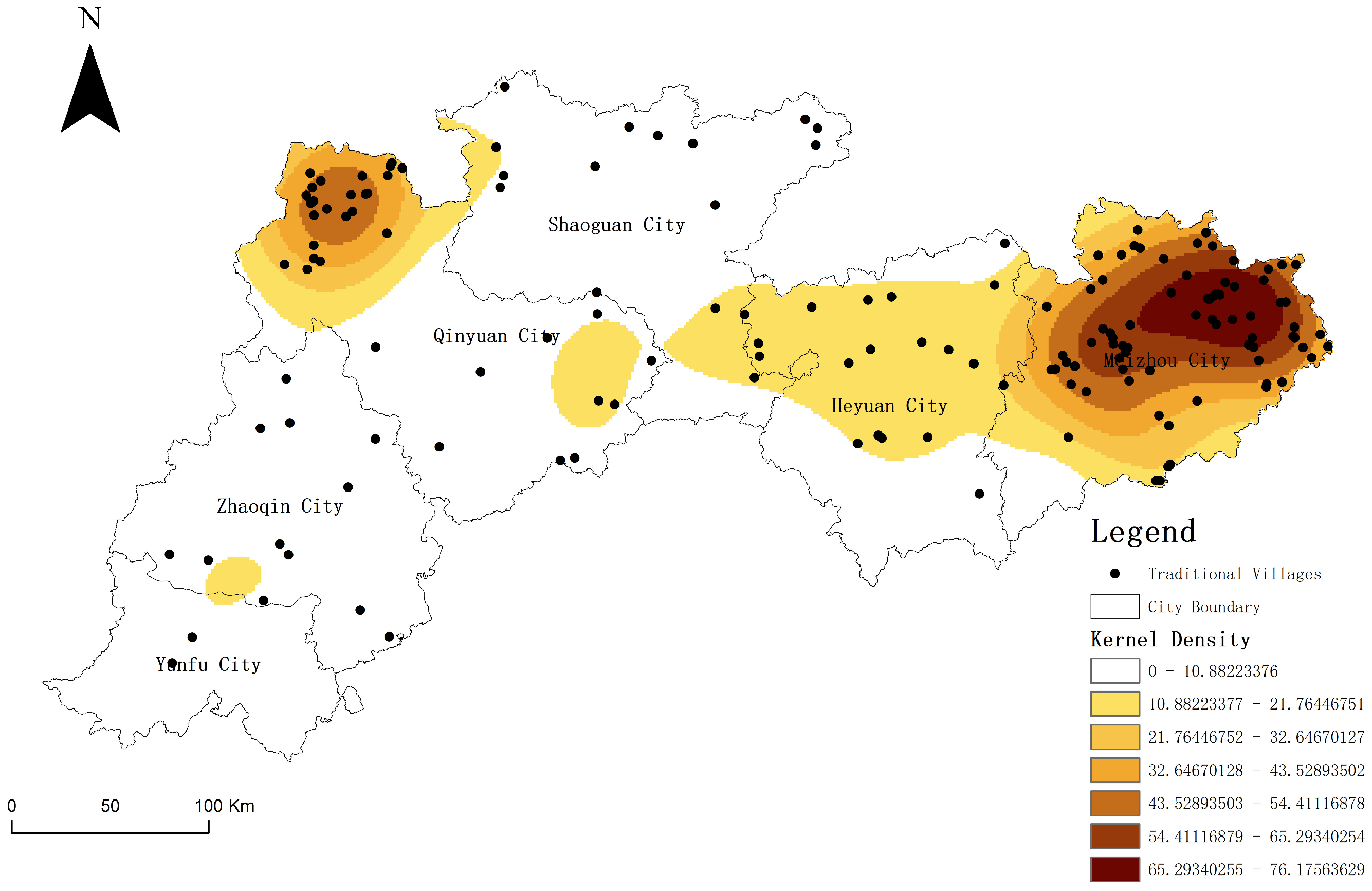

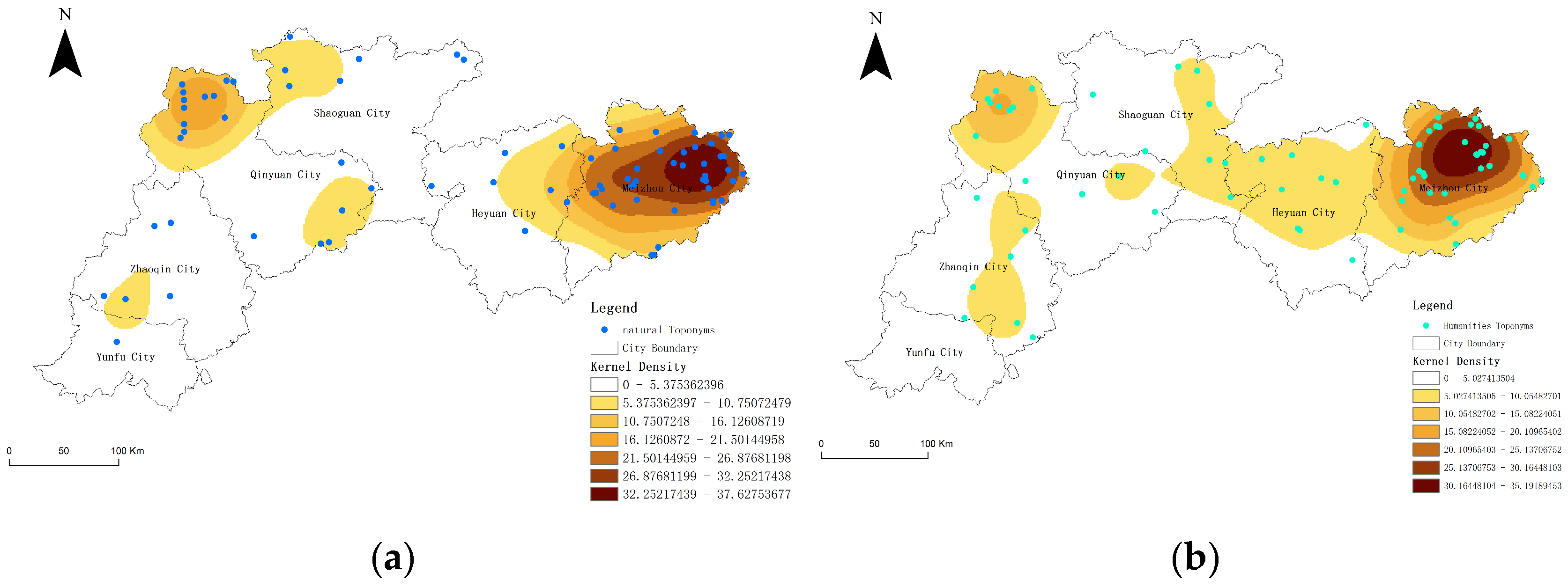

3.2. Spatial Distribution Characteristics of Toponymic Landscapes in Traditional Villages

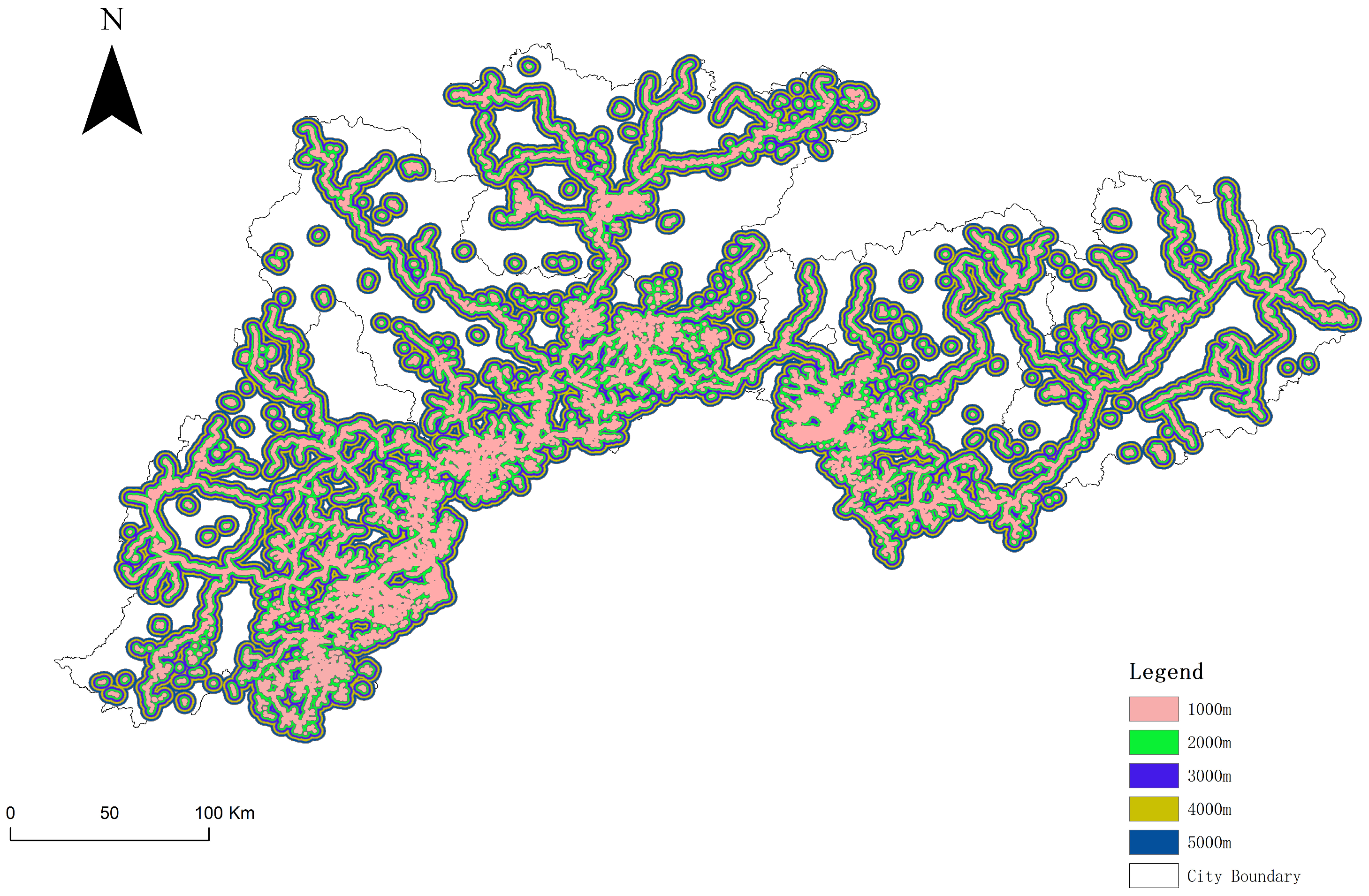

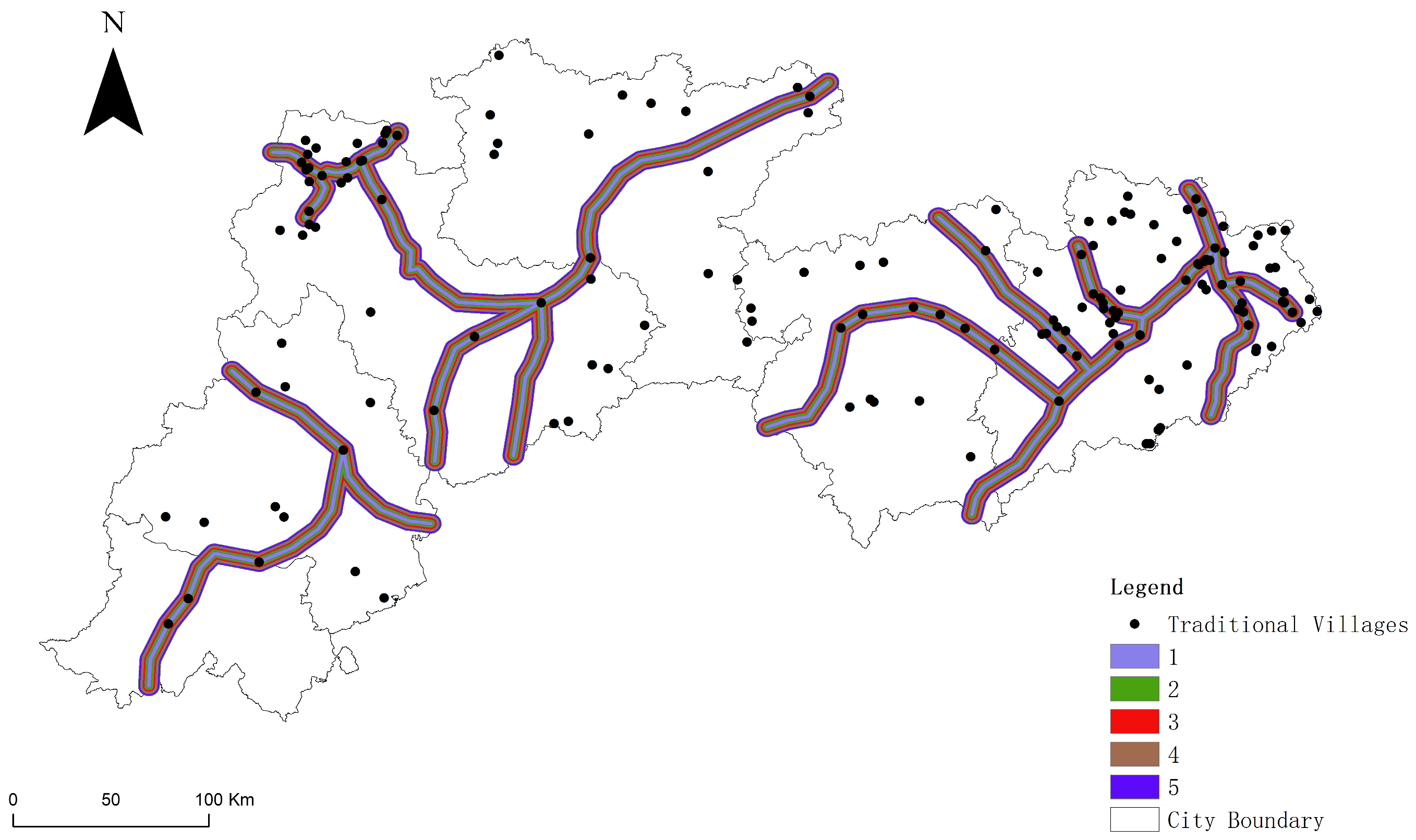

3.3. Analysis of Site Selection Characteristics of Traditional Villages

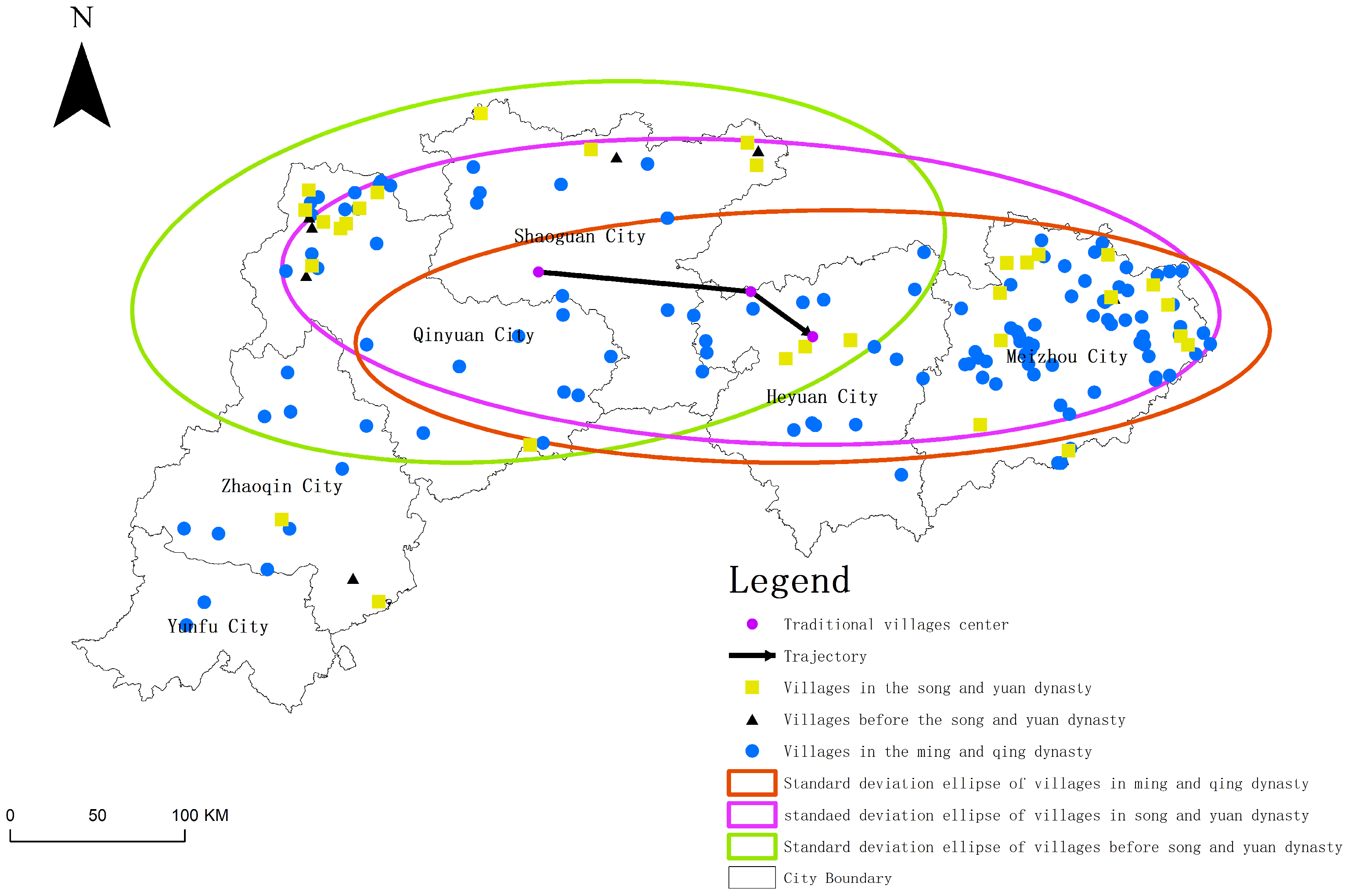

3.4. Spatiotemporal Evolution Characteristics of Toponyms in Traditional Villages

4. Analysis of the Formation Origins of Traditional Village Toponyms

4.1. Natural Geographical Factors

4.2. Economic Activity Factors

4.3. Factors of Population Migration

4.4. Cultural Factors

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- In the dimension of physical geography, the spatial distribution of villages is significantly constrained by topography and hydrological patterns, with settlements primarily concentrated in hilly and gently undulating mountainous areas. These regions feature gentle terrain, high development potential, favorable farming conditions, and residential safety, making them optimal locations for village sites. Slope analysis indicates that over 80% of villages are located on gentle slopes with gradients of less than 5°, highlighting the traditional settlements’ strong dependence on topographical suitability. At the same time, proximity to water is one of the core driving factors in site selection. Villages are often laid out along river valley plains, where water systems not only serve as support systems for agricultural irrigation and daily living needs but also improve regional accessibility, thereby promoting spatial clustering and the evolutionary diffusion of villages.

- (2)

- In the dimension of human geography, the cultural landscape construction of village toponyms profoundly reflects the combined influence of Confucian culture and migration culture. The Confucian concepts of “clan ethics” and “harmony between heaven and humanity” are particularly prominent in the naming of toponyms. Through the use of symbols such as surnames, moral vocabulary, and auspicious meanings, toponyms are imbued with cultural identity and an educative function, reinforcing the social structural order of village spaces.

- (3)

- In the dimension of historical economic activities, the spatial evolution of toponyms reflects the dual driving forces of agricultural development and the expansion of transportation networks. During the Song and Yuan Dynasties, agricultural development in river valleys facilitated the initial clustering of villages. During the Ming and Qing Dynasties, with the improvement of ancient post roads, the spatial layout of villages gradually concentrated along transportation routes. This dynamic evolutionary process demonstrates the role of economic activities in the adaptive adjustment and reconstruction of human settlement spaces, uncovering the underlying mechanisms of the cultural landscape of village toponyms. Additionally, the deep integration of Central Plains migrants and Hakka culture has created diverse cultural symbols, as reflected in the spatial distribution of toponyms associated with legends and symbolic meanings. This cultural narrative, carried by toponyms, materializes historical memory and regional identity within the spatial landscape, constructing cultural imagery and an emotional connection to these villages.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhou, Y.; Liu, M.; Xie, G.; Liu, C. Landscape ecology analysis of traditional villages: A case study of Ganjiang River Basin. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, S.; Du, J.; Tian, Z.; Zhang, Y. Investigating the spatial distribution mechanisms of traditional villages from the human geography region: A case study of Jiangnan, China. Ecolog. Inform. 2024, 81, 102649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhuang, Z.; Fang, Y. A review and prospect of research on the protection of traditional Chinese villages based on CiteSpace. J. Hengyang Norm. Univ. 2023, 6, 16–24. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, K.; Lin, W.; Fan, L.; Yang, S.; Zhang, T. Spatial Differentiation and Influencing Factors of Traditional Villages in Fujian, China: A Watershed Perspective. Sustainability 2024, 11, 4787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Tan, D.; Zhou, Y.; Xie, Y.; Chen, Z. Traditional village perception and protection behavior: The mediating role of local identity and the impact of different population differences. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2024, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, C.; Qiu, Y. Selected Laws and Regulations on the Protection of Historical and Cultural Cities, Towns, Villages and Traditional Villages; China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, L. Guidance Manual for the Protection of Traditional Chinese Villages; Xueyuan Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Liu, S.; Mao, Z.; Hou, Q. Spatial distribution characteristics and protection system scheme of traditional Chinese villages. J. Hunan Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2021, 2, 152–160. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, N. Activating Nostalgia: The Inheritance and Reconstruction of Traditional Village Cultural Ecology. Jiangsu Soci. Sci. 2024, 1, 146–155. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, Y. The current situation, value significance and path exploration of traditional village protection. Acad. Res. 2023, 12, 47–53. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.; Wang, Y. A review of relevant research on the impact of rural tourism on the development of traditional villages in my country in the past 20 years. J. Hebei Univ. Techn. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2023, 15, 85–95. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, N.; Zeng, P. Spatial distribution pattern and formation mechanism of Tianjin place name cultural landscape. Arid Land Resour. Environ. 2022, 36, 194–201. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q.; Sun, P. Spatial distribution characteristics and causes of rural place name cultural landscape in the Three Gorges Reservoir area (Chongqing section). J. Mt. Sci. 2024, 1, 108–122. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, D. Introduction to the Historiography of Place Names; China Social Sciences Press: Beijing, China, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, R.; Chen, J. Spatial pattern and influencing factors of cultural landscape of common place names in the Yangtze River Delta region. Geogr. Res. 2022, 3, 764–776. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, X.; Wang, W. Review and Prospect of Toponymy Research since the Critical Turn. Prog. Geogr. 2016, 7, 910–919. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, R.; Gao, M. The evolution of enclosure name landscape since the Qing Dynasty from the perspective of cultural ecology. Arid Land Resour. Environ. 2023, 8, 169–177. [Google Scholar]

- Adom, D. The place and voice of local people, culture, and traditions: A catalyst for ecotourism development in rural communities in Ghana. Sci. Afr. 2019, 6, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Delgado, F.J.; Martínez-Puche, A.; Lois-González, R.C. Heritage, tourism and local development in peripheral rural spaces: Mértola (Baixo Alentejo, Portugal). Sustainability 2020, 21, 9157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Zheng, H. An exploration of place name culture in Yunnan Province from the perspective of sense of place. J. Southwest For. Univ. (Soc. Sci.) 2023, 4, 102–110. [Google Scholar]

- Indraswara, M.S.; Suprapti, A.; Sardjono, A.B.; Hilmy, M.F.; Pribadi, S.B. Maintaining Sense of Place in a Historic Village: Insights from the Pekalongan Arabic Village, Indonesia. J. Int. Soc. Study Vernac. Settl. 2023, 10, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekakis, S.; Dragouni, M. Heritage in the making: Rural heritage and its mnemeiosis at Naxos island, Greece. J. Rural Stud. 2020, 77, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Wu, Y. Genetic information chain and bionic model construction of place name cultural landscape: Taking the place names of the South China Sea Islands as an example. World Geogr. Res. 2023, 10, 28–40. [Google Scholar]

- Makhzoumi, J.M. Unfolding landscape in a Lebanese village: Rural heritage in a globalising world. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2009, 15, 317–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Herman SS, B.; Salih, S.A.; Ismail, S.B. Sustainable Characteristics of Traditional Villages: A Systematic Literature Review Based on the Four-Pillar Theory of Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, B.; Mu, J. Cultural memory theory and the reconstruction of traditional village cultural space: A case study of Korean traditional villages in Yanbian. Chin. Cult. Herit. 2023, 5, 51–58. [Google Scholar]

- Jiao, Q. Study on the Factors That Influence Memory Perception of Conventional Village Space—Taking Luxiang Ancient Village as an Example. Acad. J. Archit. Geotech. Eng. 2023, 8, 43–48. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo, J.A.Q.; Narbarte, J.; Iriarte, E. What is a village? Agricultural landscapes, collective action and medieval villages in northern Iberia. Antiquity 2023, 395, 1279–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Nasundalai, S. Study on the spatial distribution characteristics of multilingual place names in Xinjiang. World Geogr. Res. 2021, 5, 1106–1114. [Google Scholar]

- Bohua, L.; Sha, Y.; Peilin, L.; Yindi, D.O.U. Spatial Distribution of Traditional Villages and Influence Factors in Hunan Province. J. Landsc. Res. 2016, 8, 63. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Ouyang, W.; Zhang, D. The spatial distribution characteristics and influencing factors of traditional villages in Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region. Sustain. Dev. 2022, 15, 632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Xue, Y.; Shang, C. Spatial distribution analysis and driving factors of traditional villages in Henan province: A comprehensive approach via geospatial techniques and statistical models. Herit. Sci. 2023, 11, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, A.; Liang, X. GIS-based analysis of the spatial distribution and influencing factors of traditional villages in Hebei Province, China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Zeng, P.; Zhang, H.; Chang, Y. Spatial distribution characteristics and causes of cultural landscape of village names in Jinan. J. Surv. Map. Sci. Technol. 2020, 3, 319–324. [Google Scholar]

- Shang, H.; Chen, P.; Luo, Y. The spatial distribution characteristics and influencing factors of traditional villages in Qiandongnan Prefecture. J. Landsc. Stud. 2021, 13, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, X.; Chen, Z. Spatial distribution characteristics of place name cultural landscape in Hehuang Valley, Qinghai. J. Cap. Norm. Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2023, 44, 83–91. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, L.; Wang, Z.; Chen, X. Spatial distribution characteristics and influencing factors of traditional villages on the Tibetan Plateau in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Wang, J.; Jin, Y. The spatial distribution characteristics and influencing factors of traditional villages in the hilly and gully areas of northern Shaanxi Province. Sustain. Dev. 2022, 22, 15327. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, S.; Hu, X. Temporal and spatial characteristics and influencing factors of settlement place name cultural landscape from the perspective of ancient waterways: A case study of the Yuanshui River Basin in Hunan Province. Geogr. Res. 2024, 1, 214–235. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Yang, X.; Feng, X.; Yan, P.; Shen, Y.; Li, X. The spatial distribution and site selection adaptation mechanism of traditional villages along the Yellow River in Shanxi and Shaanxi provinces. River Res. Appl. 2023, 39, 1270–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, D.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, B. Traditional Village Landscape Integration Based on Social Network Analysis: A Case Study of the Yuan River Basin in South-Western China. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, G. Driving mechanism and optimization path of traditional village style protection in ethnic minority areas under the perspective of rural revitalization. Natl. Stud. Qinghai 2024, 35, 65–73. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Yang, B. Spatial pattern, generation mechanism and protection strategy of Tibetan village place names: A case study of Xiahe County, Gannan Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture. Geogr. Res. 2019, 38, 784–793. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Fan, W.; Yuan, X.; Li, J. Spatial distribution characteristics and influencing factors of traditional villages based on geodetector: Jiarong Tibetan in Western Sichuan, China. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 11700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao’an, D.; Zu, J. Using geospatial technology and statistical models to analyze the spatial distribution characteristics and driving factors of ethnic minority villages in China. J. Mt. Sci. 2024, 21, 2770–2789. [Google Scholar]

- Miao, Q.; Hu, D. Spatial distribution and influencing factors of traditional villages in central Henan Province. J. Taiyuan Norm Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2024, 23, 79–86. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Hong, J.; Niu, F. Traditional Village Spatial Distribution and Its Influencing Factors Based on Density Field Hotspot Detection Model—Taking Southwest China as an Example. J. Nat. Sci. 2024, 46, 178–187. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, J.; Zhang, S. Spatial characteristics of the cultural landscape of traditional village names in Hunan. J. Surv. Map. 2023, 48, 220–230. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Y.; Yu, W. Study on spatial distribution characteristics and influencing factors of traditional villages in Guangdong Province. Geogr. Sci. 2017, 37, 236–243. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, B.; Xu, S. Analysis of multi-scale characteristics and influencing factors of spatial distribution of traditional villages: A case study of 263 traditional villages in Guangdong Province. Soil Water Conserv. Res. 2023, 30, 423–429. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Wang, Y. Study on the spatial distribution evolution of traditional Hakka villages in Meizhou based on GIS. Econ. Geogr. 2016, 36, 193–200. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, H.; Cao, X. Research on the characteristics and evolution of the historical spatial and temporal pattern of rural settlements from the perspective of inheritance: A case study of Lianzhou City, Guangdong Province. Human Geogr. 2012, 27, 87–91. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Li, F. “Regional” interpretation of the eight scenic spots of Foshan ancient villages from the perspective of cultural ecology. Chin. Gard. 2020, 36, 91–95. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, S.; Tang, G. Spatial distribution pattern of traditional villages in Guangdong and its ethnic characteristics. Trop. Geogr. 2017, 37, 318–327. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B.; Huang, X. Analysis of the spatial structure and landscape characteristics of the language and culture of place names in Guangdong. Human Geogr. 2012, 27, 39–44. [Google Scholar]

- Qingyuan City Place Names Committee. Qingyuan City Place Names; Guangdong Provincial Map Publishing House: Guangzhou, China, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Meizhou City Place Names Committee. Place Names of Meizhou City, Guangdong Province; Guangdong Provincial Map Publishing House: Guangzhou, China, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Guangdong Provincial People’s Government Local Chronicles Office. Village Conditions of Guangdong; South China University of Technology Press: Guangzhou, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, H.; Miao, H. Spatial pattern and causes of traditional villages in Northwest China. Econ. Geogr. 2021, 41, 233–240. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, C.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, D. Study on spatial distribution characteristics and influencing factors of traditional villages in Yunnan Province. J. Guizhou Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2022, 39, 97–104. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C.; Wan, C. Study on the spatiotemporal evolution characteristics of traditional villages in Dabie Mountains, western Anhui Province. Reg. Res. Dev. 2023, 42, 174–180. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, X.; Zhao, J. Study on the spatiotemporal differentiation characteristics and driving mechanisms of traditional villages in Shanxi Province. J. Taiyuan Norm. Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2023, 22, 87–96. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Yu, L.; Yue, Y. Analysis of the cultural landscape of rural place names in Taihang Mountains based on GIS: A case study of Licheng County, Shanxi Province. Arid Land Res. Environ. 2022, 36, 68–76. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Z.; Dong, S.; Yang, W. Analysis of the cultural landscape of place names in Changchun based on GIS. J. Chang. Norm. Univ. 2023, 42, 119–127. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, L.; Wang, J.; Zeng, J.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y. Analysis on the characteristics and influencing factors of place name cultural landscape in Hong’an County, Hubei Province. Mod. Urban Res. 2024, 3, 14–21. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, H.; Luo, T.; Zhang, Y.; He, Q. Spatial distribution characteristics of cultural landscape of village names in Fujian Province. J. Urban Stud. 2024, 3, 80–88. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, W.; Zhou, C. Quantitative extraction and analysis of basic morphological types of China’s landforms. J. Geo-Inf. Sci. 2009, 6, 725–736. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, Y. The impact of place name classification methods on the spatial differences of village place name cultural landscape: A case study of Minqin County, Gansu Province. Mod. Urban Stud. 2022, 4, 24–29. [Google Scholar]

- He, M.; Ding, X. Study on the spatial distribution of rural place names in Zhuji from a geomorphological perspective. J. Surv. Map. 2020, 11, 147–153. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D.; Zhou, H. Temporal and spatial evolution characteristics and causes of cultural landscape of traditional village names in Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region. J. Northwest Norm. Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2023, 59, 77–83. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, L.; Su, Y.; Yue, Y.; Niu, J. Cultural landscape pattern and driving mechanism of ancient village names in the Fenhe River Basin. J. Hainan Norm. Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2022, 2, 219–228. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; He, H. Maritime trade and economic changes in northern Guangdong during the Qing Dynasty. Acad. Res. 2010, 6, 99–104. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.; Li, H. On the comprehensive land management and protection and utilization of linear cultural heritage: Connection and integration—A case study of the Gutian section of the Meiguan Ancient Road in the Nanyue Ancient Post Road, Guangdong Province. Trop. Geogr. 2024, 3, 379–392. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, Z. Study on the protection of ancient Hakka villages in southern Jiangxi from the perspective of cultural ecology. J. Anhui Agri. Sci. 2013, 41, 7232–7234. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Zhou, Z.; Feng, Q.; Li, G.; Zhang, K. Research and progress on the cultural ecology of ethnic minority settlements in Southwest China. J. West For. Sci. 2020, 49, 147–153. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Yang, D.; Xiao, D. Regional differentiation and formation mechanism of traditional settlement and residential cultural landscape in Hainan Island. Urban Dev. Res. 2020, 5, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, Y. Love for the Place; The Commercial Press: Beijing, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

| Type | Main Words | |

|---|---|---|

| Natural toponymic landscape | Topography | Po, Ping, Keng, Ling |

| Hydrology | Stream, pond, source, water | |

| Plants and animals | Fish, peach, orchid | |

| Geographical location | Up, down, east, west | |

| Cultural toponymic landscape | Last name | Deng, Li |

| Farming | Field | |

| Architecture | Dam, bridge, dam | |

| Legends and stories | Natural disasters, culture and education | |

| Natural disasters, culture and education | Ren, Wen, Feng | |

| Category | Meizhou City | Heyuan City | Shaoguan City | Qingyuan City | Zhaoqing City | Yunfu City | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natural toponymic landscape | Topography | 17 | 4 | 2 | 11 | 2 | 0 |

| Water system | 13 | 2 | 5 | 6 | 2 | 1 | |

| Plants and animals | 11 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Cultural toponymic landscape | Surname | 5 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Geographical Orientation | 5 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | |

| Cultivation | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Architecture | 5 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 0 | |

| Legends and folktales | 12 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 0 | |

| Auspicious meaning | 6 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| Others | Others | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 1 |

| Total | 76 | 18 | 14 | 35 | 9 | 3 |

| Terrain | Number of Traditional Villages/pcs | Percentage/% |

|---|---|---|

| Plains | 5 | 3.125 |

| Hills | 97 | 60.625 |

| Small rolling hills | 50 | 31.25 |

| Medium rolling hills | 7 | 4.375 |

| Large rolling hills | 1 | 0.625 |

| Slope/° | Number of Traditional Villages/pcs | Percentage Proportion/% |

|---|---|---|

| 0–5 | 131 | 81.8 |

| 5–10 | 18 | 11.2 |

| 10–15 | 7 | 4.4 |

| 15–20 | 2 | 1.3 |

| 20–25 | 2 | 1.3 |

| Aspect | Number of Traditional Villages/pcs | Percentage Proportion/% |

|---|---|---|

| Flat | 0 | 0 |

| North | 9 | 5.6 |

| Northeast | 20 | 12.5 |

| East | 33 | 20.6 |

| Southeast | 22 | 13.8 |

| South | 24 | 15 |

| Southwest | 20 | 12.5 |

| West | 16 | 10 |

| Northwest | 12 | 7.5 |

| North | 4 | 2.5 |

| Distance from Main Roads/km | Number of Traditional Villages/pcs | Percentage Proportion/% |

|---|---|---|

| 0–1 | 61 | 38.1 |

| 1–2 | 24 | 15 |

| 2–3 | 8 | 5 |

| 3–4 | 6 | 3.75 |

| 4–5 | 9 | 9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, J.; Xiao, Y.; Yan, J.; Liang, C.; Zhong, H. Spatiotemporal Evolution Characteristics and Causative Analysis of Toponymic Cultural Landscapes in Traditional Villages in Northern Guangdong, China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 271. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17010271

Li J, Xiao Y, Yan J, Liang C, Zhong H. Spatiotemporal Evolution Characteristics and Causative Analysis of Toponymic Cultural Landscapes in Traditional Villages in Northern Guangdong, China. Sustainability. 2025; 17(1):271. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17010271

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Jun, Yao Xiao, Jiangyu Yan, Chen Liang, and Haiyan Zhong. 2025. "Spatiotemporal Evolution Characteristics and Causative Analysis of Toponymic Cultural Landscapes in Traditional Villages in Northern Guangdong, China" Sustainability 17, no. 1: 271. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17010271

APA StyleLi, J., Xiao, Y., Yan, J., Liang, C., & Zhong, H. (2025). Spatiotemporal Evolution Characteristics and Causative Analysis of Toponymic Cultural Landscapes in Traditional Villages in Northern Guangdong, China. Sustainability, 17(1), 271. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17010271