Consumer Citizenship Behavior in Online/Offline Shopping Contexts: Differential Impact of Consumer Perceived Value and Perceived Corporate Social Responsibility

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Consumer Citizenship Behavior (CCB)

2.2. Consumer Perception

2.2.1. Consumer Perceived Value (CPV)

2.2.2. Consumer Perceived Corporate Social Responsibility (CPCSR)

2.3. Online versus Offline Shopping Contexts

3. Hypotheses

3.1. Consumer Perception and Recommendation Behavior

3.2. Consumer Perception and Feedback Behavior

3.3. Consumer Perception and Helping Behavior

3.4. Consumer Perception and Tolerance Behavior

4. Methodology

4.1. Sample Characteristics and Data Acquisition

4.2. Reliability, Validity, and Model Fit

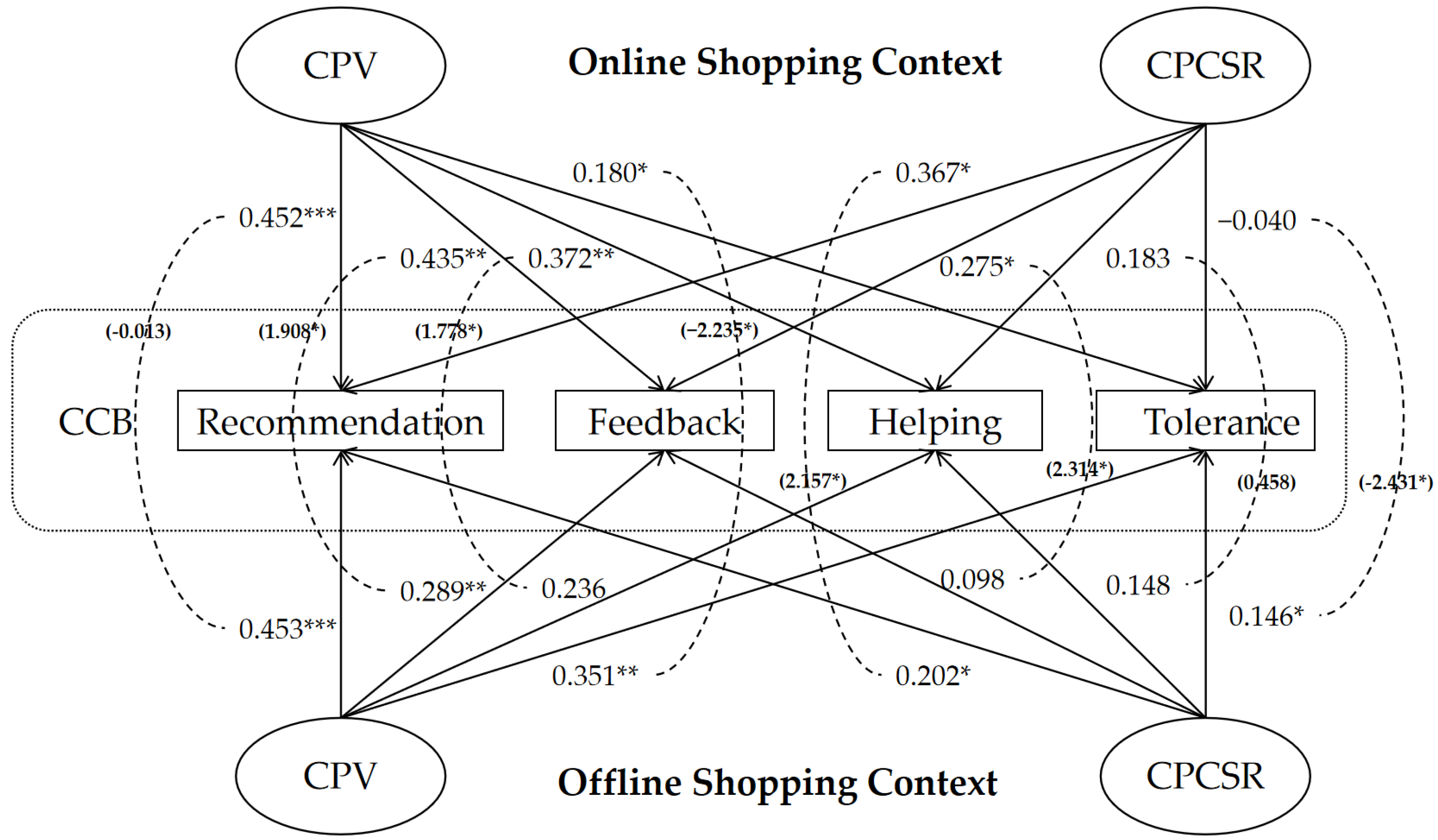

5. Results

6. Discussion

6.1. The Impact of Consumer Perception on CCB

6.2. The Varying Impact of Online versus Offline Shopping Contexts

6.2.1. The Impact towards Recommendation Behaviors

6.2.2. The Impact towards Feedback Behaviors

6.2.3. The Impact on Helping Behaviors

6.2.4. The Impact towards Tolerance Behaviors

7. Conclusions, Implications and Limitations

7.1. Conclusions

7.2. Implications

7.2.1. Theoretical Implications

7.2.2. Practical Implications

7.3. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Natarajan, T.; Ramanan, D.V.; Jayapal, J. Does Pickup Service Quality Explain Buy Online Pickup In-Store Service User’s Citizenship Behavior? Moderating Role of Product Categories and Gender. TQM J. 2023. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Tong, S.; Fang, Z.; Qu, Z. Frontiers: Machines vs. Humans: The Impact of Artificial Intelligence Chatbot Disclosure on Customer Purchases. Mark. Sci. 2019, 38, 937–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.W.; Gong, T.; Zhang, R.; Zhou, M. Do Employee Citizenship Behaviors Lead to Customer Citizenship Behaviors? The Roles of Dual Identification and Service Climate. J. Serv. Res. 2017, 20, 28–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rather, R.A. Customer Experience and Engagement in Tourism Destinations: The Experiential Marketing Perspective. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2020, 37, 15–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Tang, L.R. The Role of Customer Behavior in Forming Perceived Value at Restaurants: A Multidimensional Approach. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 87, 102–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljarah, A. The Nexus between Corporate Social Responsibility and Target-Based Customer Citizenship Behavior. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 2044–2063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatma, M.; Khan, I. Impact of CSR on Customer Citizenship Behavior: Mediating the Role of Customer Engagement. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groth, M. Customers as Good Soldiers: Examining Citizenship Behaviors in Internet Service Deliveries. J. Manag. 2015, 31, 421–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, E.S.A.; Marzouk, W.G. Factors Affecting Customer Citizenship Behavior: A Model of University Students. Int. J. Mark. Stud. 2018, 10, 54–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, H.L.; Martinez, L.M.; Martinez, L.F. Sustainability Efforts in the Fast Fashion Industry: Consumer Perception, Trust and Purchase Intention. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2020, 12, 571–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P.; Keller, K.L. Marketing Management, 15th ed.; Pearson Education Limited: Harlow, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Solomon, M. Consumer Behavior: Buying, Having, and Being, 12th ed.; Pearson: Harlow, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gale, B.T. Managing Customer Value; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Woodruff, R.B. Customer Value: The Next Source for Competitive Advantage. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1997, 25, 139–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ru, D.; Jantan, A.H.B. The Intervening Role of Customer Loyalty and Self-Efficacy on the Relationship Between Customer Satisfaction, Customer Trust, Customer Commitment, Customer Value and Customer Citizenship Behavior in Hospitality Industry in Guangdong, China. J. Int. Bus. Manag. 2023, 6, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarado-Herrera, A.; Bigne, E.; Aldas-Manzano, J.; Curras-Perez, R. A Scale for Measuring Consumer Perceptions of Corporate Social Responsibility Following the Sustainable Development Paradigm. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 140, 243–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitell, S.J. A Case for Consumer Social Responsibility (CnSR): Including a Selected Review of Consumer Ethics/Social Responsibility Research. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 130, 767–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öberseder, M.; Schlegelmilch, B.B.; Murphy, P.E.; Gruber, V. Consumers’ Perceptions of Corporate Social Responsibility: Scale Development and Validation. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 124, 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanbarpour, T.; Gustafsson, A. How Do Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and Innovativeness Increase Financial Gains? A Customer Perspective Analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 140, 471–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handelman, J.M.; Arnold, S.J. The Role of Marketing Actions with a Social Dimension: Appeals to the Institutional Environment. J. Mark. 1999, 63, 187–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Li, N. The Impact of CSR on the Performance of a Dual-Channel Closed-Loop Supply Chain under Two Carbon Regulatory Policies. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakubczak, A.; Gotowska, M. Green Consumerism vs. Greenwashing. Eur. Res. Stud. J. 2020, 23, 167–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Feng, L.; Xu, B.; Deng, W. Operation Strategies for an Omni-channel Supply Chain: Who is Better Off Taking on the Online Channel and Offline Service? Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2020, 39, 100918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homburg, C.; Lauer, K.; Vomberg, A. The Multichannel Pricing Dilemma: Do Consumers Accept Higher Offline than Online Prices? Int. J. Res. Mark. 2019, 36, 597–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratchford, B.; Soysal, G.; Zentner, A.; Gauri, D.K. Online and Offline Retailing: What We Know and Directions for Future Research. J. Retail. 2022, 98, 152–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, O.; Somogyi, S.; Charlebois, S. Food Choice in the E-commerce Era: A Comparison between Business-to-consumer (B2C), Online-to-offline (O2O) and New Retail. Br. Food J. 2020, 122, 1215–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siragusa, C.; Tumino, A. E-grocery: Comparing the Environmental Impacts of the Online and Offline Purchasing Processes. Int. J. Logist. Res. App. 2022, 25, 1164–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, H.; Chan, C.; Mogilner, C. People Rely Less on Consumer Reviews for Experiential than Material Purchases. J. Consum. Res. 2020, 46, 1052–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savila, I.D.; Wathoni, R.N.; Santoso, A.S. The Role of Multichannel Integration, Trust and Offline-to-online Customer Loyalty towards Repurchase Intention: An Empirical Study in Online-to-offline (O2O) E-commerce. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2019, 161, 859–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y.; Gong, T. Customer Value Co-creation Behavior: Scale Development and Validation. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 1279–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, C.M.; Lee, M.K. What Drives Consumers to Spread Electronic Word of Mouth in Online Consumer-opinion Platforms. Decis. Support Syst. 2012, 53, 218–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennig-Thurau, T.; Gwinner, K.P.; Walsh, G.; Gremler, D.D. Electronic Word-of-mouth via Consumer-opinion Platforms: What Motivates Consumers to Articulate Themselves on the Internet? J. Interact. Mark. 2004, 18, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Istanbulluoglu, D.; Leek, S.; Szmigin, I.T. Beyond Exit and Voice: Developing an Integrated Taxonomy of Consumer Complaining Behaviour. Eur. J. Mark. 2017, 51, 1109–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevalier, J.A.; Mayzlin, D. The Effect of Word of Mouth on Sales: Online Book Reviews. J. Mark. Res. 2006, 43, 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, L.; Lotz, S.L. Exploring Antecedents of Customer Citizenship Behaviors in Services. Serv. Ind. J. 2018, 38, 607–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, J.; Wang, W.; Du, P.; Filieri, R. Impact of Brand Community Supportive Climates on Consumer-to-consumer Helping Behavior. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2023, 17, 434–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-J.; Hyun, B.-H. Effects of Psychological Variables on the Relationship between Customer Participation Behavior and Repurchase Intention: Customer Tolerance and Relationship Commitment. Economies 2022, 10, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syah, T.Y.R.; Olivia, D. Enhancing Patronage Intention on Online Fashion Industry in Indonesia: The Role of Value Co-Creation, Brand Image, and E-Service Quality. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2022, 9, 2065790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaosmanoglu, E.; Altinigne, N.; Isiksal, D.G. CSR Motivation and Customer Extra-Role Behavior: Moderation of Ethical Corporate Identity. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 4161–4167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Canio, F.; Fuentes-Blasco, M.; Martinelli, E. Extrinsic Motivations Behind Mobile Shopping: What Drives Regular and Occasional Shoppers? Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2022, 50, 962–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Du, H.S.; Shen, K.N.; Zhang, D. How Gamification Drives Consumer Citizenship Behaviour: The Role of Perceived Gamification Affordances. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2022, 64, 102127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oke, A.; McKenzie, K.; Osobajo, O.; Lawani, A. Effects of Millennials Willingness to Pay on Buying Behaviour at Ethical and Socially Responsible Restaurants: Serial Mediation Analysis. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2023, 113, 103507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, P.G.; Spreng, R.A. Modelling the Relationship between Perceived Value, Satisfaction, and Repurchase Intentions in a Business-to-Business Service Context: An Empirical Examination. Int. J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 1997, 8, 414–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Mao, J. Hedonic or Utilitarian? Exploring the Impact of Communication Style Alignment on User’s Perception of Virtual Health Advisory Services. J. Interact. Mark. 2015, 35, 229–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Yin, X.; Lee, G. The Effect of CSR on Corporate Image, Customer Citizenship Behaviors, and Customers’ Long-Term Relationship Orientation. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 88, 102–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Han, X.; Ding, L.; He, M. Organic Food Corporate Image and Customer Co-developing Behavior: The Mediating Role of Consumer Trust and Purchase Intention. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 59, 102377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, P.; Khajeheian, D.; Soleimani, M.; Gholampour, A.; Fekete-Farkas, M. User Engagement in Social Network Platforms: What Key Strategic Factors Determine Online Consumer Purchase Behaviour? Econ. Res.-Ekon. Istraživanja 2023, 36, 2106264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Men, L.R.; Tsai, W.H.S. Beyond liking or Following: Understanding Public Engagement on Social Networking Sites in China. Public Relat. Rev. 2013, 39, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itani, O.S.; Kassar, A.N.; Loureiro, S.M.C. Value Get, Value Give: The Relationships Among Perceived Value, Relationship Quality, Customer Engagement, and Value Consciousness. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 80, 78–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khawaja, L.; Ali, A.; Mostapha, N. The Mediating Effect of Customer Satisfaction in Relationship with Service Quality, Corporate Social Responsibility, Perceived Quality and Brand Loyalty. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2021, 11, 763–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godey, B.; Manthiou, A.; Pederzoli, D.; Rokka, J.; Aiello, G.; Donvito, R.; Singh, R. Social Media Marketing Efforts of Luxury Brands: Influence on Brand Equity and Consumer Behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 5833–5841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L. Satisfaction, Inertia, and Customer Loyalty in the Varying Levels of the Zone of Tolerance and Alternative Attractiveness. J. Serv. Mark. 2011, 25, 310–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, P.O.; Assaker, G. Examining the Antecedents and Effects of Hotel Corporate Reputation on Customers’ Loyalty and Citizenship Behavior: An Integrated Framework. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2022, 31, 640–661. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.; Weisstein, F.L.; Duan, S.; Choi, P. Impact of Ambivalent Attitudes on Green Purchase Intentions: The Role of Negative Moods. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2022, 46, 182–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filho, E.P.; Añez, M.E.M. Why Are You So Tolerant? Towards the Relationship between Consumer Expectations and Level of Involvement. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 60, 102467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Cude, B.J. Consumer Complaint Channel Choice in Online and Offline Purchases. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2012, 36, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, S.M.; Sardinha, I.M.D.; Reijnders, L. The Effect of Corporate Social Responsibility on Consumer Satisfaction and Perceived Value: The Case of the Automobile Industry Sector in Portugal. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 37, 172–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, K.; Han, H.; Kim, T.H. The Relationships among Overall Quick-casual Restaurant Image, Perceived Value, Customer Satisfaction, and Behavioral Intentions. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2008, 27, 459–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ailawadi, K.L.; Neslin, S.A.; Luan, Y.J.; Taylor, G.A. Does Retailer CSR Enhance Behavioral Loyalty? A Case for Benefit Segmentation. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2014, 31, 156–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, W.M.; Kim, H.; Kim, H.K. Does Customer Engagement in Corporate Social Responsibility Initiatives Lead to Customer Citizenship Behaviour? The Mediating Roles of Customer-Company Identification and Affective Commitment. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 1258–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error: Algebra and Statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, R.A. The Design of Experiments; Oliver & Boyd: Edinburgh, UK, 1935. [Google Scholar]

- Pitman, E.J.G. Significance Tests which may be Applied to Samples from Any Populations II: The Correlation Coefficient. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B 1937, 4, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitman, E.J.G. Significance Tests which may be Applied to Samples from Any Populations III: The Analysis of Variance Test. Biometrika 1938, 29, 322–335. [Google Scholar]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The General Causality Orientations Scale: Self-determination in Personality. J. Res. Personal. 1985, 19, 109–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P. On the Concept of Intentional Social Action in Consumer Behavior. J. Consum. Res. 2000, 27, 388–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batson, C.D.; Shaw, L.L. Evidence for Altruism: Toward a Pluralism of Prosocial Motives. Psychol. Inq. 1991, 2, 107–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, K.L. Conceptualizing, Measuring, and Managing Customer-Based Brand Equity. J. Mark 1993, 57, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, S.; Bhattacharya, C.B. Does Doing Good Always Lead to Doing Better? Consumer Reactions to Corporate Social Responsibility. J. Mark. Res. 2001, 38, 225–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godes, D.; Mayzlin, D. Using Online Conversations to Study Word-of-Mouth Communication. Mark. Sci. 2004, 23, 545–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dellaert, B.G.C.; Arentze, T.A.; Timmermans, H.J. Shopping Context and Consumers’ Mental Representation of Complex Shopping Trip Decision Problems. J. Retail. 2008, 84, 219–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, R.D. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community; Simon & Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Lee, K.-H. Multiple Routes for Social Influence: The Role of Compliance, Internalization, and Social Identity. Soc. Psychol. Quart. 2002, 65, 226–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamari, J.; Lehdonvirta, V. Game Design as Marketing: How Game Mechanics Create Demand. Int. J. Bus. Sci. Appl. Manag. 2010, 3, 34–49. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, M.A.; Fischer, E.; Yongjian, C. How Does Brand-related User-generated Content Differ Across YouTube, Facebook, and Twitter? J. Interact. Mark. 2012, 26, 102–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemon, K.N.; Verhoef, P.C. Understanding Customer Experience throughout the Customer Journey. J. Mark. 2016, 80, 69–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susskind, A.M.; Kacmar, K.M. Customer Loyalty During a Service Failure and Recovery: The Role of Affect and Attribution. J. Bus. Psychol. 2009, 24, 67–81. [Google Scholar]

- White, K.; Dahl, D.W. To Be Pragmatic or Restrained? The Impact of Inclination and Opportunity on the Use of Hedonic and Utilitarian Strategies in Online Shopping. J. Retail. 2007, 83, 155–172. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, S.; Bhattacharya, C.B. Does It Pay to be Good? A Meta-analysis and Examination of the Relationship between Corporate Social Performance and Financial Performance. J. Mark. 2001, 65, 56–66. [Google Scholar]

| Dimensions | Manifestations | |

|---|---|---|

| Online | Offline | |

| Recommendation |

|

|

| Feedback |

|

|

| Helping |

|

|

| Tolerance |

|

|

| M | S.D. | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. CPV | 3.862 | 0.680 | (0.810) | |||||

| 2. CPCSR | 3.765 | 0.703 | 0.628 ** | (0.792) | ||||

| 3. Recommendation | 3.367 | 0.899 | 0.565 ** | 0.488 ** | (0.780) | |||

| 4. Feedback | 3.313 | 0.967 | 0.427 ** | 0.373 ** | 0.629 ** | (0.789) | ||

| 5. Helping | 3.406 | 0.944 | 0.353 ** | 0.304 ** | 0.563 ** | 0.738 ** | (0.829) | |

| 6. Tolerance | 3.187 | 0.824 | 0.382 ** | 0.286 ** | 0.317 ** | 0.324 ** | 0.374 ** | (0.731) |

| Model | Independent Variable | Explanatory Variable | Coefficients | t-Value | VIF | F-Value | R2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta | S.D. | |||||||

| 1 | Recommendation | CPV | 0.450 | 0.098 | 6.054 *** | 1.679 | 37.192 | 0.358 |

| CPCSR | 0.231 | 0.095 | 3.132 ** | 1.657 | ||||

| 2 | Feedback | CPV | 0.338 | 0.118 | 4.081 *** | 1.679 | 17.382 | 0.201 |

| CPCSR | 0.182 | 0.113 | 2.206 * | 1.657 | ||||

| 3 | Helping | CPV | 0.294 | 0.119 | 3.431 ** | 1.679 | 12.284 | 0.148 |

| CPCSR | 0.150 | 0.114 | 1.759 | 1.657 | ||||

| 4 | Tolerance | CPV | 0.339 | 0.104 | 3.939 *** | 1.679 | 11.354 | 0.137 |

| CPCSR | 0.080 | 0.100 | 0.938 | 1.657 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shen, Q.; Du, Y.; Huang, J. Consumer Citizenship Behavior in Online/Offline Shopping Contexts: Differential Impact of Consumer Perceived Value and Perceived Corporate Social Responsibility. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2968. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16072968

Shen Q, Du Y, Huang J. Consumer Citizenship Behavior in Online/Offline Shopping Contexts: Differential Impact of Consumer Perceived Value and Perceived Corporate Social Responsibility. Sustainability. 2024; 16(7):2968. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16072968

Chicago/Turabian StyleShen, Qiulian, Yuxuan Du, and Jingxian Huang. 2024. "Consumer Citizenship Behavior in Online/Offline Shopping Contexts: Differential Impact of Consumer Perceived Value and Perceived Corporate Social Responsibility" Sustainability 16, no. 7: 2968. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16072968

APA StyleShen, Q., Du, Y., & Huang, J. (2024). Consumer Citizenship Behavior in Online/Offline Shopping Contexts: Differential Impact of Consumer Perceived Value and Perceived Corporate Social Responsibility. Sustainability, 16(7), 2968. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16072968